Occult hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can be defined as the long lasting persistence of viral genome in the liver tissue of patients without HBV surface antigen (HBsAG), with or without antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen (anti‐HBc) or hepatitis B surface antigen (anti‐HBs).1 The clinical relevance of occult B infection is well documented.2,3,4,5,6 Immunosuppressive therapy can promote viral replication and disease progression. Discontinuation of immunosuppressive drugs may lead to the reconstitution of the immune response to the virus and hence to immune mediated destruction of infected hepatocytes. This is a well recognised occurrence in patients with hepatitis B infection or non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).7,8

We studied the prevalence of occult HBV infection in 58 consecutive NHL patients, six of whom were HBsAG positive and 52 were not. Echo assisted liver biopsy specimens were obtained from the right hepatic lobe of all patients. Epidemiological and clinical data are reported in table 1. Serum and liver tissues from the patients were tested for occult HBV infection; tests were considered positive when two of the three HBV fractions were detected.2 DNA extracted from liver and serum was tested for the genomic fragment of the core antigen with real time polymerase chain reaction to titrate the amount of viral DNA.

Table 1 Epidemiological and clinical data of the case study.

| HBsAG− | HBsAG+ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti‐HBc+ | Anti‐HBc+ | Anti‐HBc− | ||

| Anti‐HBs+ | ||||

| Number | 18 | 3 | 31 | 6 |

| Age (years) (range) | 58 (51 to 70) | 52 (46 to 73) | 44 (28 to 71) | 53 (47 to 70) |

| Sex (M/F) | 8/10 | 2/1 | 11/20 | 4/2 |

| HCV | 8 | – | 7 | – |

| Lymphoma grading low/intermediate/high | 8/6/4 | 0/2/1 | 10/11/10 | 3/1/1/1 maltoma |

| Previous treatment with lamivudine | – | – | – | 6 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus.

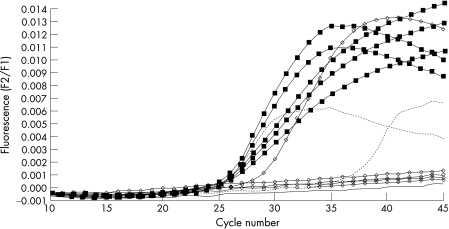

We identified the occult virus only in anti‐HBc+ patients who did not have HCV co‐infection or other serological markers of HBV infection (that is, anti‐HBs). Occult infection was found in five of 18 anti‐HBc positive patients and only in liver tissue, not in serum. All these patients, after discontinuation of chemotherapy, experienced HBV reactivation (severe increase in alanine amino transferase (ALT), high serum levels of HBV‐DNA, HBsAg+, anti‐HBc IgM+) which was managed with nucleoside analogues. Six months later nucleoside analogues were discontinued and all patients except one had recovered (normal ALT, negative serum HBV‐DNA, anti‐HBC IgG+). The patient who had not recovered remained serum HBsAg positive, whereas all the others had the same HBV marker profile (only anti‐HBc IgG positivity) that they had before reactivation (fig 1).

Figure 1 Quantitative hepatitis (HBV)‐DNA analysis during (linked squares) and after (linked circles) reactivation in occult HBV infected patients. HBV‐DNA was detectable in all patients during reactivation. HBV‐DNA was detected in only one patient who remained HBsAg positive after recovery. No HBV‐DNA was detected in the other four patients after recovery. Standard curves, dotted lines; H2O, continuous line. Each curve represents an individual patient.

We assayed the serum HBV‐DNA titre in an attempt to find a cut off value that might discriminate between patients with and without occult infection. Even using a highly sensitive method (real time polymerase chain reaction) to titrate HBV‐DNA in serum, it was not possible to discriminate between the two groups of patients. However, HBV‐DNA titration in liver tissue discriminated subjects with and without detectable occult B infection (mean HBV‐DNA values, 3.7×105 copies/mg and 3.67×102 copies/mg, respectively, p<0.04). Consequently, liver biopsy and the detection of occult B infection in liver tissue may help to decide whether to initiate pre‐emptive treatment with nucleoside analogues. However, this is far from being a routine diagnostic approach in clinical practice, and the only alternative might be a wait‐and‐watch policy in which antiviral therapy is given upon the virological/clinical occurrence of B virus replication/reactivation.9

In conclusion, the prevalence of anti‐HBc positive subjects among Italian individuals with HBsAG/anti‐HBs negative NHL is as high as 35%. These were the only patients in whom occult HBV infection was detected, and the prevalence was as high as 28%. Therefore, anti‐HBc positive patients undergoing chemotherapy may be at high risk of severe HBV reactivation. Liver biopsy should be suggested in these patients and occult infection sought, as they may benefit from pre‐emptive treatment with nucleoside analogues. Frequent serum HBV‐DNA titration might also be useful to predict HBV reactivation and so initiate early treatment with nucleoside analogues.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Raimondo G. Pollicino T, Cacciola I, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 200746160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacciola I, Pollicino T, Squandrito G.et al Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with chronic hepatitis C liver disease. N Engl J Med 199934122–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda R, Ishimura N, Niigaki M.et al Serologically silent hepatitis B virus coinfection in patients with hepatitis C virus‐associated chronic liver disease: clinical and virological significance. J Med Virol 199958201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz S J. Use of hepatitis B core antibody‐positive donors for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 20028S82–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rizzetto M. Transmission of hepatitis B infection from hepatitis B core antibody‐positive livers: background and prevention. Liver Transpl 20017518–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Persico M, De Marino F, Di Giacomo Russo G.et al Efficacy of lamivudine to prevent hepatitis reactivation in hepatitis B virus‐infected patients treated for non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 200299724–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau J Y N, Lai C L, Lin H J.et al Fatal reactivation of chronic hepatitis B infection following withdrawal of chemotherapy in lymphoma patients. Q J Med 198973911–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang R H S, Lok A S F, Lai C L.et al Hepatitis B infection in patients with lymphoma. Hematol Oncol 19908261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui C K, Cheung W W, Zhang H Y.et al Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg‐negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 200613159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]