Abstract

Background

Hemoclips, injection therapy and thermocoagulation (heater probe or electrocoagulation) are the most commonly used types of endoscopic hemostasis for the control of non‐variceal gastrointestinal bleeding.

Aim

To compare the efficacy of hemoclips versus injection or thermocoagulation in endoscopic hemostasis by pooling data from the literature.

Method

Publications in the English literature (MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane Library) as well as abstracts in major international conferences were searched using the keywords “hemoclips” and “bleeding”, and 15 trials fulfilling the search criteria were found. Outcome measures included: initial hemostasis (after endoscopic intervention); recurrent bleeding; definitive hemostasis (no recurrent bleeding until the end of follow‐up); the requirement for surgical intervention; and all‐cause mortality. The heterogeneity of trials was examined and the effects were pooled by meta‐analysis.

Results

Of 1156 patients recruited in the 15 studies, 390 were randomly assigned to receive clips alone, 242 received clips combined with injection, 359 received injection alone, and 165 received thermocoagulation with or without injection. Definitive hemostasis was higher with hemoclips (86.5%) than injection (75.4%; RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.00–1.30), or endoscopic clips with injection (88.5%) compared with injections alone (78.1%; RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03–1.23), leading to a reduced requirement for surgery but no difference in mortality. Compared with thermocoagulation, there was no improvement in definitive hemostasis with clips (81.5% versus 81.2%; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.77–1.31). These estimates were robust in sensitivity analyses. There was also no difference between clips and thermocoagulation in rebleeding, the need for surgery and mortality. The reported locations of failed hemoclip applications included posterior wall of duodenal bulb, posterior wall of gastric body and lesser curve of the stomach.

Conclusion

Successful application of hemoclips is superior to injection alone but comparable to thermocoagulation in producing definitive hemostasis. There was no difference in all‐cause mortality irrespective of the modalities of endoscopic treatment.

Keywords: upper gastrointestinal bleeding, clips, injections, thermocoagulation, endoscopic hemostasis

Acute non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding remains a common medical problem associated with significant morbidity and mortality and healthcare resource use. Large population‐based studies and collaborative databases have estimated the annual incidence of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding at approximately 50 to 170 per 100 000 population.1,2,3,4,5 The case fatality of upper gastrointestinal bleeding is approximately 5–10%, either directly caused by the bleeding episode or through decompensation in concurrent medical illnesses.1,2,3,4,5

Endoscopic therapy has generally been recommended as the first‐line treatment for upper gastrointestinal bleeding as it has been shown to reduce recurrent bleeding, the need for surgery and mortality.6 The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines stated that no single modality has been shown to be superior for treating upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by peptic ulcer disease.7 The United Kingdom guidelines suggested that hemoclips are particularly useful for actively bleeding large vessels, but pointed out that they may be difficult to apply to awkwardly placed ulcers.8 The Non‐variceal Upper GI Bleeding Conference Group, which consisted mostly of Canadian experts gave most discrete recommendations: (1) no single method of endoscopic injection is superior to the others; (2) no single method of endoscopic thermal coaptive therapy is superior to the others; and (3) the placement of clips is a promising endoscopic hemostasis therapy for high‐risk stigmata.9 There are, however, variable successes in the literature with hemostasis using endoscopic clips, which may reflect difficulties with their placement.

Studies comparing clips with other endoscopic treatment modalities have yielded conflicting results. Most studies using clips have been limited by relatively small sample sizes and, in some cases, reporting outcomes only of patients in whom clips were successfully placed rather than performing an intention‐to‐treat analysis.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 There are also variations in study design, entry criteria and outcome criteria. The endoscopic techniques used were also dissimilar in that some combined clips with injection (i.e. to stop bleeding first with injection therapy before applying clips), whereas others used clips alone in actively bleeding ulcers. We performed a meta‐analysis based on published data to determine whether the use of endoscopic clips benefits patients with non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Methods

We performed a search using the relevant keywords of “hemoclips” and “peptic ulcer bleeding” to identify randomized clinical trials in full publications of the English literature from different computerized databases: MEDLINE (1950 to January 2007), EMBASE (1980 to January 2007), and the Cochrane Centre Register of Controlled Trials (1st quarter 2007). We also manually searched the abstracts published in major international conferences (Digestive Disease Week, United European Gastrointestinal Week and Asia Pacific Digestive Week) over the past 10 years, and scanned the articles from the bibliographies of retrieved trials.

We included all trials that randomly assigned patients to hemoclips or alternative therapies (thermocoagulations or injections) for treating non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Randomized controlled trials were included if they met the following criteria: (1) applied endoscopic therapy only to active bleeding ulcers or ulcers with adherent blood clot or protuberant vessels (Forret I, IIa and IIb); (2) used a concurrent control group; (3) concomitant therapy was applied equally to both intervention arms; (4) diagnosis of acute bleeding from peptic ulcers or Dieulafoy lesions was made endoscopically; (5) at least one of the following outcomes was reported: initial hemostasis after first endoscopic therapy; rebleeding; definitive hemostasis, surgical intervention; mortality; and (6) it was possible to isolate data for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers. We excluded patients with the diagnosis of bleeding Mallory Weiss tear. Bleeding from a Mallory Weiss tear is often self‐limiting and runs a benign course.

The primary outcome of this study is definitive hemostasis defined as the successful control of bleeding after the first endoscopic therapy until the end of follow‐up. Secondary outcomes include initial hemostasis (control of bleeding after the first endoscopic treatment), rebleeding (clinical evidence of recurrent bleeding after first endoscopic therapy), surgery and death from any cause (30‐day mortality or “in‐hospital” mortality). A flowchart outlining our outcome definitions are presented in fig 1.

Figure 1 A simple flowchart for peptic ulcer or Dieulafoy bleeding treatment.

Two investigators (K.K.T., L.H.L.) independently assessed the papers generated for relevancy, and only rejected papers that fulfilled the following explicit exclusion criteria: (1) not written in English for abstract; (2) not related to bleeding peptic ulcers or Dieulafoy lesions; and (3) not concerning a clinical question regarding human subjects. We reviewed each identified trial and determined inclusion. Investigators also independently abstracted the data into a standardised data extraction form. When discrepancies were found, the third investigator (J.J.S.) would make the definitive decision for trial eligibility and data extraction.

The quality of each trial was assessed on the basis of five criteria: (1) study described as prospectively randomized; (2) randomization by concealed allocation or computer‐generated allocation; (3) listing of exclusion criteria for ineligible patients; (4) clear definitions of outcomes, i.e. initial hemostasis, recurrent bleeding and definitive hemostasis; and (5) pre‐defined salvage procedures when endoscopic treatment failed to control bleeding. These quality parameters have included certain “inclusion criteria” such as the use of a control group with otherwise identical concomitant therapy, and a clear definition of outcome parameters.

We performed a meta‐analysis of outcomes as appropriate by combining different groups of trials and used the Mantel–Haenszel method (RevMan, version 4.2.8). Group 1 trials compared hemoclips with injections. Group 2 trials compared hemoclips with injections versus injections alone. Group 3 trials compared hemoclips with or without injections versus thermocoagulation (heater probe or electrocoagulation) with or without injections. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated, and p < 0.1 was considered significant. We assessed heterogeneity with I2, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies caused by heterogeneity rather than chance. High values of I2 would show increasing heterogeneity. We used a fixed effects model for significant homogeneous studies. Otherwise, we applied a random effects model. All outcomes were summarized as relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals. We performed one‐way sensitivity analyses on study duration (< 4 weeks versus ε 4 weeks), adjuvant proton pump inhibitors (PPI) (yes versus no), and quality of trial (high (quality score > 3) versus low (quality score δ 3)) to test the robustness of the combined estimates.

Results

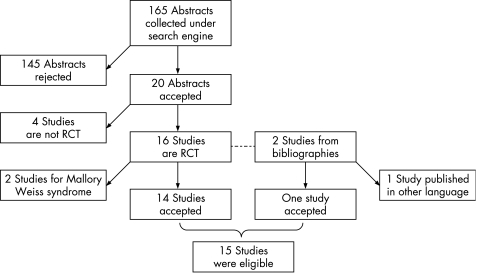

We initially identified 165 articles through database searches. All abstracts were scanned and we retrieved 18 studies and two abstracts. We excluded four studies using non‐randomized methodology and two studies recruiting Mallory Weiss syndrome with bleeding. We further identified two studies from the bibliographies of retrieved studies, but we excluded one that was published in non‐English literature. The definitive analysis in this meta‐analysis included 15 studies published from 1996 to 2006 (fig 2).

Figure 2 Results of literature search. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Among the 15 studies, eight compared the efficacy of hemoclips and injections, seven compared hemoclips with injections versus injections alone, and four compared hemoclips alone versus thermocoagulations (heater probe or electrocoagulation) with or without injections. Most studies were of high quality, with only four trials graded below 3 (table 1). A total of 1156 patients participated in these randomized trials, and the reported data collection periods were from July 1994 to July 2004. The number of participants in individual trials ranged from 18 to 113. Four trials did not report data for gender. The remaining trials included 713 (70.0%) male patients and the mean age was 61.7 years. All trials employing endoscopic clips used Olympus hemoclips, eight injection solutions used singly or in combination were mentioned, namely epinephrine (in five studies), epinephrine‐polidocanol (in three studies), hypertonic saline‐epinephrine (in three studies), absolute ethanol (in two studies), isotonic saline‐epinephrine, polidocanol or distilled water each in one study. In the thermocoagulation groups, bipolar electrocautery probes (Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) were used in one study and heater probes (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) were used in three studies.

Table 1 Quality of randomised clinical trials to compare effectiveness of hemoclips.

| Trial | Publication type | Comparison | N | Age (mean) | Gender (male%) | Study duration (weeks) | Adjuvant PPI | Quality score (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoclips versus injection | ||||||||

| Simoens, 199710 | Abstract | Hemoclips (n = 9) vs epinephrine + polidocanol (n = 9) | 18 | NA | NA | NA | No | 1 |

| Chung, 199911 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 41) vs hypertonic saline‐epinephrine (n = 41) | 82 | 56.2 | 41% | 1 | No | 3 |

| Chung, 200012 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 9) vs hypertonic saline‐epinephrine (n = 12) | 21 | 53.2 | 38% | 1 | No | 5 |

| Gevers, 200213 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 35) vs epinephrine + polidocanol (n = 34) | 69 | 65.5 | NA | 4 | No | 5 |

| Park, 200314 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 16) vs isotonic saline (n = 16) | 32 | 61.1 | 38% | 1 | No | 3 |

| Chou, 200315 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 39) vs distilled water (n = 40) | 79 | 64.0 | 39% | 8 | No | 4 |

| Shimoda, 200316 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 42) vs absolute ethanol (n = 42) | 84 | 58.8 | 35% | 8 | Yes | 3 |

| Ljubicic, 200417 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 31) vs polidocanol (n = 30) | 61 | 61.1 | 31% | <1 | Yes | 2 |

| Hemoclips + injection versus injection | ||||||||

| Villanueva, 199618 | Abstract | Hemoclips + epinephrine (n = 42) vs epinephrine (n = 37) | 79 | NA | NA | NA | Yes | 1 |

| Simoens, 199710 | Abstract | Hemoclips + epinephrine‐polidocanol (n = 9) vs epinephrine‐polidocanol (n = 9) | 18 | NA | NA | NA | No | 1 |

| Chung, 199911 | Full‐text | Hemoclips + hypertonic saline‐epinephrine (n = 41) vs hypertonic saline‐epinephrine (n = 41) | 82 | 56.2 | 41% | 1 | No | 3 |

| Gevers, 200213 | Full‐text | Hemoclips + epinephrine + polidocanol (n = 32) vs epinephrine + polidocanol (n = 34) | 66 | 65.5 | NA | 4 | No | 5 |

| Shimoda, 200316 | Full‐text | Hemoclips + absolute ethanol (n = 42) vs absolute ethanol (n = 42) | 84 | 58.8 | 35% | 8 | Yes | 3 |

| Park, 200419 | Full‐text | Hemoclips + epinephrine (n = 23) vs epinephrine (n = 45) | 68 | 62.0 | 43% | 1 | Yes | 5 |

| Lo, 200620 | Full‐text | Hemoclips + epinephrine (n = 52) vs epinephrine (n = 53) | 105 | 63.5 | 38% | 8 | Yes | 5 |

| Hemoclips versus thermocoagulation | ||||||||

| Cipolletta, 200121 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 56) vs heater probe (n = 57) | 113 | 58.0 | 26% | 4 | Yes | 5 |

| Lin, 200222 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 40) vs heater probe (n = 40) | 80 | 65.9 | 44% | 2 | Yes | 5 |

| Lin, 200323 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 46) vs heater probe + epinephrine (n = 47) | 93 | 65.8 | 40% | 2 | Yes | 5 |

| Saltzman, 200524 | Full‐text | Hemoclips (n = 26) vs bipolar electrocautery probe + epinephrine (n = 21) | 47 | 65.1 | 36% | 8 | Yes | 5 |

NA, Not available in the content of the study; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

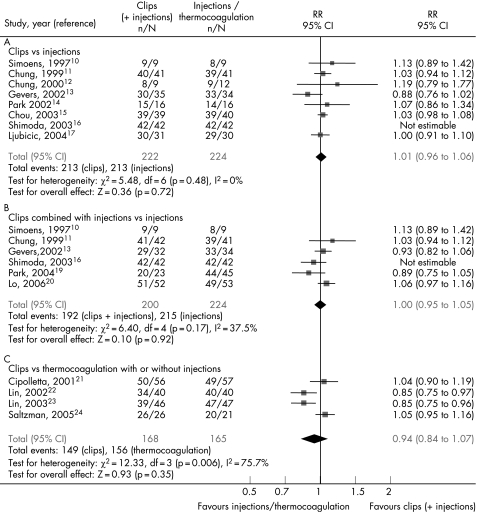

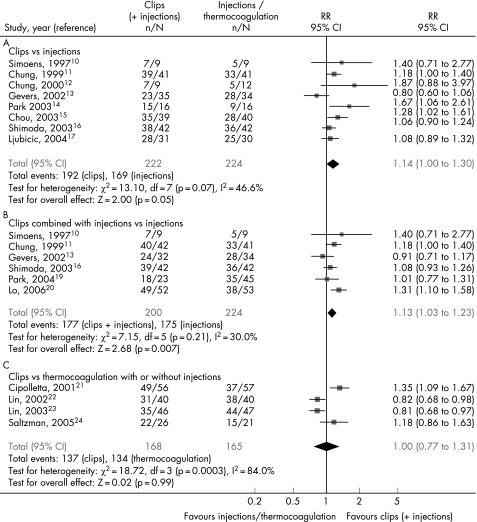

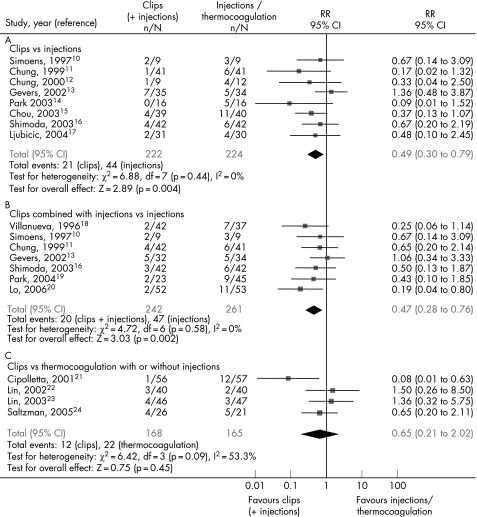

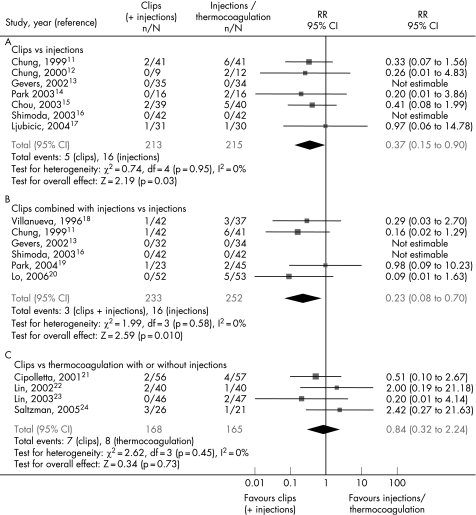

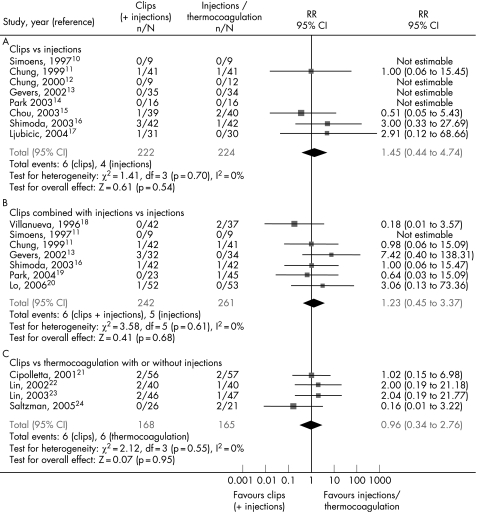

Clips versus injections

Eight trials were identified for the comparison of hemoclips alone with injections alone. Statistical heterogeneity was only found for the outcomes of definitive hemostasis (I2 = 46.6%, p = 0.07). No significant difference in initial hemostasis was found between hemoclips alone (95.9%) versus injection alone therapy (95.1%; RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.06; fig 3A). The results from a random effect model showed a marginally significantly higher probability of achieving definitive hemostasis with hemoclips (86.5%) than injection (75.4%; RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.30; fig 4A). Besides, hemoclips showed a significant reduction in rebleeding (9.5%) compared with injection (19.6%; RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.79; fig 5A) and the need for surgery (2.3% vs 7.4%; RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.90) in the fixed effects models (fig 6A). An insignificant difference in all‐cause mortality was, however, found comparing the two modalities of treatment; pooled rates were 2.7% in the hemoclip group and 1.8% in the injection group (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.44 to 4.74; fig 7A).

Figure 3 Forest plots for initial hemostasis comparison.

Figure 4 Forest plots for definitive hemostasis comparison.

Figure 5 Forest plots for rebleeding comparison.

Figure 6 Forest plots for the need for surgery comparison.

Figure 7 Forest plots for mortality comparison.

Clips combined with injections versus injections alone

Seven trials were identified for the comparison of endoscopic clips combined with injections versus injections alone. Statistical heterogeneity was not found among these trials for all outcomes (p > 0.1). No significant difference was found in initial hemostasis between hemoclips combined with injections (96.0%) versus injections alone (96.0%; RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.05; fig 3B). A significantly higher definitive success in hemostasis was found in endoscopic clips with injection (88.5%) than with injections alone (78.1%; RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.23; fig 4B). Furthermore, clips combined with injections showed a significant reduction in rebleeding (8.3% vs 18.0%; RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.76; fig 5B) and the need for surgery (1.3% vs 6.3%; RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.70; fig 6B) using the random effect model. An insignificant difference in all‐cause mortality has been demonstrated comparing the two treatment modalities; the pooled rates were 2.5% in the combined hemoclip group and 1.9% in the injection group (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.45 to 3.37; fig 7B).

Clips versus thermocoagulation with or without injection

Four trials were identified for the comparison of hemoclips versus thermocoagulation with or without injections. Statistical heterogeneities were found among the trials for the outcomes of initial hemostasis (I2 = 75.7%, p = 0.006), definitive hemostasis (I2 = 84.0%, p < 0.001), and rebleeding (I2 = 53.3%, p = 0.09). Initial hemostasis was insignificantly different between hemoclips (88.7%) and thermocoagulation (94.5%; RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.07; fig 3C). Definitive hemostasis of clips (81.5%) and thermocoagulation (81.2%) were comparable (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.31; fig 4C). There was no difference between clips and thermocoagulation in rebleeding (7.1% vs 13.3%; RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.02; fig 5C), the need for surgery (4.2% vs 4.8%; RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.32 to 2.24; fig 6C) and all‐cause mortality (3.6% vs 3.6%; RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.34 to 2.76; fig 7C) in the fixed effects model.

Sensitivity analyses

One‐way sensitivity analyses showed that the results on initial hemostasis, definitive hemostasis, rebleeding and the need for surgery are very consistent based on study durations, the use of adjuvant PPI, and the qualities of trials (table 2). There was no difference in the risk of mortality when comparing clips with or without injections versus injections alone. As there were only four trials comparing clips versus thermocoagulation, no sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Table 2 Results of sensitivity analyses.

| No. of trials | Combined relative risks (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial hemostasis | Definitive hemostasis | Rebleeding | Need for surgery | Mortality | ||

| Clips versus injections | ||||||

| All trials | 8 | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.30) | 0.49 (0.30 to 0.79) | 0.37 (0.15 to 0.90) | 1.45 (0.44 to 4.74) |

| Study duration | ||||||

| Shorter (< 4 weeks) | 4 | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.05) | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.32) | 0.59 (0.29 to 1.20) | 0.39 (0.12 to 1.27) | 1.64 (0.22 to 12.2) |

| Longer ( 4 weeks) | 3 | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.56) | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.80) | 0.34 (0.09 to 1.35) | 1.35 (0.31 to 5.89) |

| Adjuvant proton pump inhibitors | ||||||

| Yes | 2 | 1.00 (0.91 to 1.10) | 1.07 (0.94 to 1.21) | 0.59 (0.23 to 1.54) | 0.97 (0.06 to 14.8) | 2.97 (0.48 to 18.3) |

| No | 6 | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.07) | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.49) | 0.46 (0.26 to 0.81) | 0.33 (0.12 to 0.86) | 0.68 (0.12 to 3.95) |

| Quality | ||||||

| High (> 3) | 3 | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.15) | 1.14 (0.75 to 1.74) | 0.62 (0.32 to 1.21) | 0.36 (0.09 to 1.46) | 0.51 (0.05 to 5.43) |

| Low ( 3) | 5 | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.10) | 1.17 (1.06 to 1.29) | 0.39 (0.19 to 0.78) | 0.37 (0.11 to 1.20) | 2.18 (0.50 to 9.53) |

| Clips with injection versus injections | ||||||

| All trials | 7 | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.23) | 0.47 (0.28 to 0.76) | 0.23 (0.08 to 0.70) | 1.23 (0.45 to 3.37) |

| Study duration | ||||||

| Shorter (< 4 weeks) | 4 | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.13) | 1.11 (0.96 to 1.28) | 0.54 (0.22 to 1.36) | 0.31 (0.07 to 1.32) | 0.81 (0.10 to 6.33) |

| Longer ( 4 weeks) | 3 | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.16) | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.35) | 0.30 (0.11 to 0.78) | 0.09 (0.01 to 1.63) | 1.68 (0.23 to 12.5) |

| Adjuvant Proton pump inhibitors | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.98 (0.82 to 1.18) | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29) | 0.31 (0.16 to 0.63) | 0.28 (0.07 to 1.02) | 0.70 (0.19 to 2.64) |

| No | 3 | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 1.09 (0.94 to 1.25) | 0.80 (0.39 to 1.64) | 0.16 (0.02 to 1.29) | 3.07 (0.05 to 18.7) |

| Quality | ||||||

| High (> 3) | 3 | 0.97 (0.87 to 1.09) | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | 0.45 (0.22 to 0.93) | 0.27 (0.05 to 1.35) | 2.87 (0.59 to 14.1) |

| Low ( 3) | 4 | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.13) | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29) | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.94) | 0.21 (0.05 to 0.94) | 0.53 (0.12 to 2.39) |

Failure of clips

Four studies described the failure of clip application as a result of the awkward position of ulcers.20,21,22,23 Positions described as difficult for clips were posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, posterior wall gastric body and lesser curve of the stomach. Among them, the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb was the most commonly described position.

Discussion

The pooled data of 15 studies indicated that endoscopic clipping, with or without injection, is superior to endoscopic injection alone in the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer and bleeding Dieulafoy lesions. Clipping gives a higher rate of definitive hemostasis after a single treatment with less rebleeding and less requirement for surgery. On the other hand, comparing endoscopic clipping with thermal therapy showed no distinct advantage. There was no demonstrable difference in hemostasis, no difference in surgery and mortality.

In this study, we have excluded Mallory Weiss syndrome, vascular ectasia, esophageal erosion and gastritis although, together they constitute up to 30% of cases of non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Unlike peptic ulcers and Dieulafoy lesions, bleeding from these lesions is usually self‐limiting and thus the efficacy of endoscopic treatment is hard to evaluate. Most studies in this meta‐analysis used similar inclusion criteria for patients who had high‐risk peptic ulcer or Dieulafoy lesions (i.e. either actively bleeding or showing a protuberant vessel or adherent clot). This is in line with the international guidelines.7,8,9 All studies used the same endoscopic clip, which is the hemoclip (Olympus), and that removes a potential factor of heterogeneity with different device designs. Approximately half the studies have used adjuvant PPI. This could potentially affect the outcome as high‐dose PPI have been shown to reduce recurrent bleeding and reduce surgical intervention.25,26 On the other hand, only two out of eight studies comparing endoscopic clipping with endoscopic injection used adjuvant PPI. Nevertheless, there is some degree of heterogeneity introduced that necessitates the use of a random effects model in analysis. Furthermore, sensitivity analysis did not show that by removing studies with or without using adjuvant PPI, the results remain robust. All studies comparing endoscopic clipping with thermocoagulation had used adjuvant PPI, and because of the small number of trials in this category, sensitivity analysis was not performed.

The superiority of endoscopic clipping (with or without injection) over endoscopic injection alone should not be surprising, because injection leads to transient hemostasis by tamponade effects produced by the volume of fluid injected. A previous randomised controlled trial27 and a subsequent meta‐analysis of combination therapy showed improved results over injection monotherapy.28 Endoscopic clipping producing mechanical control for bleeding vessels below the ulcer is understandably more effective than endoscopic injection in securing hemostasis in upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

There has been some debate as to whether applying injection before endoscopic clipping adds any benefit to clipping alone. Some endoscopists prefer to use clipping without injection, especially when a protruding vessel can be seen at the ulcer base. On the other hand, in a profusely bleeding ulcer, which obscures the endoscopic view, transient control of active bleeding may facilitate the precise placement of clips on the site of bleeding. Sometimes, however, injection leads to tissue edema causing difficulties in applying the clip precisely on the bleeding vessel. In the current meta‐analysis, clipping with or without injection showed consistently superior results compared with injection alone. A direct comparison of clipping versus clipping after injection is, however, not available.

Despite improvements in sustaining hemostasis by clipping or thermocoagulation leading to less rebleeding and fewer interventions with surgery, mortality has not been reduced. All‐cause mortality of the three groups of pooled data ranges from 1.8% to 3.6%, and there is no indication of a reduction in the death rate. The relatively low mortality reported in these series is likely to be related to the short follow‐up of some studies and the selection criteria of the studies. Nevertheless, it is an enigma that despite successful control of hemorrhage in many studies using various combinations of endoscopic and pharmacological therapies, the mortality rate remains unchanged. It is possible that, as we are treating an increasingly older population of upper gastrointestinal bleeding patients with frequent and significant comorbidities, gastrointestinal bleeding merely represents a terminal event of these very ill patients dying of cardiopulmonary decompensation and multi‐organ failure.

There have recently been reports of new models of endoscopic clips, including the TriClip (Cook Endoscopy, Winston‐Salem, North Carolina, USA), the Resolution Clip (Boston Scientific) and the Multi‐Clip (InScope, Ethicon, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA). Unlike the Endoclip (Olympus) which has two prongs opening from 6 mm to 12 mm, the TriClip opens to a maximum of 12 mm between the three prongs, the Resolution Clip has the ability to reopen and reposition the clip after closing for up to five times, and the Multi‐Clip can apply four clips sequentially.29 While we are awaiting head‐to‐head comparison of these devices in clinical studies, animal models in the dog showed similar efficacy in clip placement and initial hemostasis.30

In conclusion, endoscopic clipping is superior to endoscopic injection and is comparable to thermocoagulation in securing hemostasis of bleeding peptic ulcers and Dieulafoy lesions. The choice of therapy would remain at the discretion of the endoscopist based on the nature and position of the ulcer, experience of the endoscopist and previous endoscopic therapy that the patient has received.

Abbreviations

PPI - proton pump inhibitor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Blatchford O, Davidson L A, Murray W R.et al Acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in west of Scotland: case ascertainment study. BMJ 1997315510–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockall T A, Logan R F, Devlin H B.et al Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. BMJ 1995311222–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vreeburg E M, Snel P, de Bruijne J W.et al Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the Amsterdam area: incidence, diagnosis and clinical outcome. 199792236–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longstreth G F. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a population‐based study. Am J Gastroenterol 199590206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targownik L W, Nabalamba A. Trends in management and outcomes of acute non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: 1993–2003. Clin Gastroenterol and Hepatol 200641459–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook D J, Gayatt G H, Salena B J.et al Endoscopic therapy for acute non‐variceal hemorrhage: a meta‐analysis. Gastroenterology 1992102139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline: the role of endoscopy in acute non‐variceal upper GI hemorrhage. Gastroint Endosc 200460497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer K R. Non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: guideline. Gut 2002511–6.12077078 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall J K, for the Nonvariceal Upper GI Bleeding Conference Group Consensus recommendation for managing patients with non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med 2003139843–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simoens M, Gevers A M, Macken E.et al A prospective randomized trial comparing three hemostasis modalities for bleeding peptic ulcers injection therapy with epinephrine and polidocanol 1% versus hemoclip versus injection combined with hemoclip; an interim report. Gastrointest Endosc 199745AB101 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung I K, Ham J S, Kim H S.et al Comparison of the hemostatic efficacy of the endoscopic hemoclip method with hypertonic saline‐epinephrine injection and a combination of the two for the management of bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 19994913–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung I K, Kim E J, Lee M S.et al Bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and the choice of endoscopic method: comparing the hemostatic efficacy of mechanical and injection methods. Gastrointest Endosc 200052721–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gevers A M, De Goede E, Simoens M.et al A randomized trial comparing injection therapy with hemoclip and with injection combined with hemoclip for bleeding ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 200255466–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park C H, Sohn Y H, Lee W S.et al The usefulness of endoscopic hemoclipping for bleeding Dieulafoy lesions. Endoscopy 200335388–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou Y C, Hsu P I, Lai K H.et al A prospective, randomized trial of endoscopic hemoclip placement and distilled water injection for treatment of high‐risk bleeding ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 200357324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimoda R, Iwakiri R, Sakata H.et al Evaluation of endoscopic hemostasis with metallic hemoclips for bleeding gastric ulcer: comparison with endoscopic injection of absolute ethanol in a prospective, randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003982198–2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ljubicic N. Efficacy of endoscopic clipping and long‐term follow‐up of bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Hepato‐Gastroenterology 200653224–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villanueva C, Balanzo J, Sabat M.et al Injection therapy alone or with endoscopic hemoclip for bleeding peptic ulcer. Preliminary results of a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 199643361 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park C H, Joo Y E, Kim H S.et al A prospective, randomized trial comparing mechanical methods of hemostasis plus epinephrine injection to epinephrine injection alone for bleeding peptic ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc 200460173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo C C, Hsu P I, Lo G H.et al Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for epinephrine injection alone and injection combined with hemoclip therapy in treating high‐risk bleeding ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 200663767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cipolletta L, Bianco M A, Marmo R.et al Endoclips versus heater probe in preventing early recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer: a prospective and randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc 200153147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin H J, Hsieh Y H, Tseng G Y.et al A prospective, randomized trial of endoscopic hemoclip versus heater probe thermocoagulation for peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 2002972250–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin H J, Perng C L, Sun I C.et al Endoscopic haemoclip versus heater probe thermocoagulation plus hypertonic saline‐epinephrine injection for peptic ulcer bleeding. Digest Liver Dis 200235898–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saltzman J R, Strate L L, Di Sena V.et al Prospective trial of endoscopic clips versus combination therapy in upper GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol 20051001503–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau J Y W, Sung J J Y, Lee K K C.et al Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med 2000343310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leontiadis G I, Sharma V K, Howden C W. Proton pump inhibitor treatment for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syste Rev. 2004;CD002094 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Chung S C S, Lau J Y W, Sung J J Y.et al Randomized comparison between adrenaline injection alone and adrenaline injection plus heater probe treatment for actively bleeding ulcers. BMJ 19973141307–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvet X, Vergara M, Brullet E.et al Addition of a second endoscopic treatment following epinephrine injection improves outcome in high‐risk bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology 2004126441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Technology status evaluation report. Endoscopic clip application devices. Gastrointest Endosc 200663746–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen D M, Machicado G A, Hirabayashi K. Randomized controlled study of three different types of hemoclips for hemostasis of bleeding canine acute gastric ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 200664768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]