Abstract

C. albicans can adapt and grow on sorbose plates by losing one copy of Chr5. Since rad52 mutants of S. cerevisiae lose chromosomes at a high rate, we have investigated the ability of C. albicans rad52 to adapt to sorbose. Carad52-ΔΔ mutants generate Sou+ strains earlier than wild type but the final yield is lower, probably because they die at a higher rate in sorbose. As other strains of C. albicans, CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ derivatives generate Sou+ strains by a loss of one copy of Chr5 about 75% of the time. In addition, rad52 strains were able to produce Sou+ strains by a fragmentation/deletion event in one copy of Chr5, consisting of loss of a region adjacent to the right telomere. Finally, both CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ produced Sou+ strains with two apparent full copies of Chr5, suggesting that additional genomic changes may also regulate adaptation to sorbose.

Index descriptors: Sorbose adaptation, Candida albicans, Rad52, chromosome loss, chromosome fragmentation

Introduction

Candida albicans, as well as other Candida species, have become prevalent opportunistic human pathogens. Candida albicans is a diploid organism (Olaiya and Sogin, 1979) with a high degree of heterozygosity that lacks a complete sexual cycle. Still, genome sequence analysis has identified a locus (MTL, for mating type-like locus) similar to the MAT locus of S. cerevisiae (Hull and Johnson, 1999). Furthermore, strains of opposite mating type can mate whether they are genetically engineered (Hull et al., 2000) or in vitro selected (Magee and Magee, 2000). However, although there is no doubt that karyogamy follows conjugation (Bennet et al., 2005), meiosis has not been demonstrated so far and tetraploids derived from these crosses likely become diploid by a loss of chromosomes thus completing a parasexual cycle (Bennet and Johnson, 2003).

Importantly, progeny of a particular strain undergo changes in the karyotype in vitro as well as in vivo (see below). These genotypic changes are frequently accompanied by alterations in a number of phenotypic traits, an observation that has led to the widely accepted hypothesis that C. albicans can achieve phenotypic variability by genomic arrangements (Rustchenko-Bulgac et al., 1990; Rustchenko and Sherman, 2003; Magee and Chibana, 2002; Larriba, 2004). For instance, gain- and loss-of-assimilation function in vitro is associated with gross rearrangements involving chromosomes 2, 5 and 6 (Rutschenko et al, 1994). Gross chromosomal rearrangements in chromosomes 5, 6 and 7 also occur during the course of infection (Legrand et al., 2004). The systematic analysis by Rustchenko and colleagues demonstrated that in the environments that kill cells or prevent their propagation, C. albicans survives due to different specific chromosome alterations (reviewed by Rustchenko and Sherman 2003; Rustchenko, 2006). In the most detailed study of the adaptation to sorbose, it was suggested that the loss of an entire homologue of Chr5 is required because this chromosome carries multiple genes for negative regulators, which are functionally redundant. Especially relevant for some of our current results was the finding of a critical portion of 209 kb located on the right arm of Chr 5 (Kabir et al., 2005). The loss of this portion allows adaptation to sorbose, thus, mimicking the loss of an entire homologue. More recently, it has been reported that aneuploidy in general, and more specifically formation of an isochromosome composed of the two left arms of chromosome 5 were associated with azole resistance. Interestingly, this arm has ERG11 required for ergosterol biosynthesis and TAC1, which is a positive regulator of the drug efflux pump (Selmecki et al., 2006). This fact may also explain why the gain of one copy of this chromosome occurs in some C. albicans strains resistant to fluconazole (Perepnikhatka et al., 1999).

In addition to changes in karyotype, derivatives of wild type strains of C. albicans frequently show loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in several markers (Forche et al., 2004; Tavanti et al., 2004). Furthermore, it has been reported that loss of heterozygosity (LOH), caused by mutation or mitotic recombination, occurs independently at different loci across the whole genome during in vivo passage and may be accompanied or not by changes in karyotypes as well as alteration in phenotypes (Forche et al., 2005).

Studies in S. cerevisiae have indicated that loss of chromosomes is prevented by both homologous recombination (HR) and checkpoint functions. It is well known that S. cerevisiae cells lose chromosomes at a high rate in rad52 strains (Mortimer et al., 1981; Yoshida et al., 2003), as well as in rad50, rad51 and rad54 mutants (Hiraoka et al., 2000; Klein, 2001; Yoshida et al., 2003). HR acts synergistically with DNA damage checkpoints to assure the correct repair and segregation of chromosomes between the mother and daughter cells (Klein, 2001).

We have recently characterized the RAD52 from C. albicans. As expected, it is required for several cellular events that require homologous recombination, including integration of linear DNA with long flanking homology and repair of DNA damage caused by UV or the radiomimetic MMS. In the present study, we have investigated the appearance of Sou+ mutants in sorbose plates in rad52-ΔΔ strains. We have found that the absence of Rad52 leads to the earlier appearance of Sou+ mutants, but the final yield of Sou+ mutants is lower. As described for several Rad52+ strains (Janbon et al., 1998; Andaluz et al., 2002), adaptation of both CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ derivatives to sorbose mostly occurred through loss of one full copy of Chr5, but also through other genetic alterations that do not imply obvious alterations of this chromosome. Furthermore, a particular mechanism of adaptation to sorbose consisting of a long deletion of Chr5 was restricted to rad52 strains.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains and media

The C. albicans strains used in this study are indicated in Table 1. They are derived from the prototrophic strain SC5314 (Gillum et al., 1984), used in the sequencing of the genome. C. albicans cells were grown routinely at 28°C in YEPD (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto Peptone).

Table 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Parental | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Wild type | Gillum et al., 1984 | |

| CAF2 | ura3Δ::imm434/URA3 | SC5314 | Fonzi and Irwin, 1993 |

| TCR1 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | CAI4-1 | Ciudad et al., 2004 |

| RAD52/rad52Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | |||

| TCR1.1 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | TCR1 | Ciudad et al., 2004 |

| RAD52/rad52Δ::hisG | |||

| TCR2.1 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | TCR1.1 | Ciudad et al., 2004 |

| rad52Δ::hisG/rad52Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | |||

| TCR2.2 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | TCR1.1 | Ciudad et al., 2004 |

| rad52Δ::hisG/rad52Δ::hisG-URA3-hisG | |||

| TCR3.2.1 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | TCR2.2 | Ciudad et al., 2004 |

| rad52Δ::hisG/rad52Δ:: RAD52n-URA3-hisG |

2.2. Analysis of Sou+ mutants

The formation of Sou+ mutants was analyzed as described before (Andaluz et al., 2002), except that for the time course experiments, sorbose plates were inoculated with cells from a YEPD liquid culture (instead of a colony) at a cell density of about 3000-5000 cfu/plate. The viability experiment has been described before (Janbon et al., 1999; Andaluz et al., 2002). Briefly, a cell suspension from a YEPD liquid culture was appropriately diluted and about 800 cells were plated in duplicate on sorbose plates. A YEPD plate was also inoculated to provide a direct estimation of the total CFU plated. To determine the number of viable cells, at the indicated times the entire agar disc from one series of sorbose plates was transferred onto the surface of YEPD plates. The second set of plates was monitored daily to determine the number of Sou+ mutants. In order to correlate the appearance of Sou+ mutants and viability, we considered that the Sou+ mutant had been formed four (Rad52+) or five (Rad52-) days before the first visual observation of the colony (see reconstruction experiment). All Sou+ colonies were verified by growing them on new sorbose plates before being analyzed for the MTL locus, karyotype or the indicated SNP marker(s). Finally, a reconstruction experiment was performed to determine the lag time between the mutational event and the appearance of the microscopic colony. For this purpose, Sou+ cells from a colony were plated on a new sorbose plate and the time of the appearance of the colony recorded (Janbon et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2004).

2.3. Determination of heterozygosity/homozygosity of selected regions of chromosomes 2, 4 and 5

Loss of chromosome 5 was first investigated by analyzing LOH at the MTL locus. For PCR analysis of the MTL loci, we used the protocol and oligonucleotides reported (Rustad et al., 2002), except that the annealing temperature was 57°C instead 55°C. The presence of one or both homologues of Chr5 was further investigated by analyzing previously characterized single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in SfiI fragments, SNP 1445/2395 in 5M and SNP 1341/2493 in 5I, from that chromosome. These SNPs correspond to SNP110 and SNP118 respectively in the SNP map (http://albicansmap.ahc.umn.edu/html/snp.html). Similarly, for chromosome 2, we amplified and sequenced the region around the SNP marker 1314/2038 (SNP68) in SfiI fragment 2U. For these experiments, the regions containing the polymorphisms were amplified using the appropriate oligonucleotides and the PCR product sequenced. Primer sequences can be obtained upon request from Anja Forche (http://albicansmap.ahc.umn.edu/html/snp.html). A region of 1009 bp of chromosome 4, including RBT7, was investigated using oligonucleotides indicated in Table 2. The RBT7 ORF exhibits restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) for several restriction enzymes (Anja Forche, personal communication). Following purification, this band was treated with AluI and the fragments analyzed in an agarose gel. A strain homozygous for RBT7 obtained in our laboratory was used as a control.

Table 2.

Primers used in this studya)

| RBT7 | F 5′-GAGTGAAAAATAAGTGACGAAC-3′ |

| R 5′-TTAGGATGTACCACACTTCATC-3′ | |

| ILV3 | F 5′-ATGGCTATGGGAAGACACAACAGA-3′ |

| R 5′-AACGGCATTAGTAGAACCACCAGT-3′ | |

| HST1 | F 5′-GCCATCTTCGGGACATTATCGACT-3′ |

| R 5′-CCCACATGCTTGGAAGATACCATC-3) | |

| RAD17 | F 5′-GTTGGGGGTTGATTTGAGTTTGAT-3′ |

| R 5′-ACCCATGCGCGTCTTTGATAA-3′ |

Primers sequences were retrieved from the C. albicans genome database. Primers for RBT7 were obtained from A. Forche.

2.4. DNA extraction and analysis

Standard techniques were routinely used for DNA manipulations (Sherman et al., 1982). Genomic DNA was prepared from protoplasts obtained by the incubation of cells with Zymolyase stabilized with 1M sorbitol and lysed in 50 mM Tris, 50 mM EDTA, 0.6% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

2.5. Preparation of native chromosomes

A 0.1-ml sample of an exponentially growing culture of C. albicans was used to inoculate 10-ml of YEPD. The culture was maintained in a rotatory shaker at 30°C for 48 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, and suspended in 1-ml of CPES (40 mM citric acid, 120 mM sodium phosphate, 20 mM EDTA, pH 8, 1.2 M sorbitol and 5 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with 0.2 mg of Zymolyase 20,000A. A 1-ml aliquot of CPE (same as CPES but lacking sorbitol and DTT) containing 1% low-melting-point agarose at 50°C was then added and gently mixed. Aliquots of 200 μl were then transferred into a sample mold and kept at -20°C. Upon solidification, plugs were transferred to test tubes, supplemented with 6 ml of CPE and incubated at 30°C for 4 h. CPE buffer was replaced with 5 ml of TESP buffer (1M Tris-HCl, 0.5 M EDTA, 2% SDS, 1 mg/ml of proteinase K) and incubated overnight at 50°C. Samples were then washed 3x with TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA) at 50°C and 6x at room temperature. The plugs were stored at 4°C in 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.

2.6. Electrophoretical chromosome separation

Two different protocols were then used to separate chromosomes. In the first protocol, all chromosomes were separated but homologues of chromosomes 6 and 7 can not be distinguished. The gel samples were electrophoresed in 0.6% agarose for 24 h at 80 V with a 120-300 sec linear ramp and then for 48 h at 80 V with a 420-900 sec linear ramp in a rotating-gel electrophoresis apparatus (Rotaphor, Biometra) using TBE buffer (0.5x, pH 8). A second protocol was also used to separate both homologues of the smaller chromosomes, 6 and 7 (Legrand et al., 2004; Lephard et al., 2005). In this case, the gel samples were run in 1% agarose at 100V with a linear ramp of 60-120 sec, 120° included angle for 48 h and then at 130V with a 300-420 sec linear ramp, 120° included angle for 48 h in the same apparatus. The intensity of the ethidium bromide fluorescence was quantified with the Corel Photo-Paint program.

2.7. Southern blot analysis

For Southern blotting, electrophoresed samples were transferred to TM-nitrocellulose and hybridized with the probes (below) at high stringency (65°C in 6× SSC, 5×Denhardt’s solution, 0.5% SDS and then washed with 0.1x SSC, 0.1% SDS). The probes consisted of: 1) markers of SfiI fragments of Chr5 (CDC1 for 5I and GCD11 for 5M (kindly provided by BB Magee); 2) a 521 bp probe specific of RAD17 located close to the left telomere in SfiI fragment 4BB; 3) a 456 bp probe of ILV3, an ORF located in SfiI fragment 5I at the telomere-proximal side of HIS1 (Wu et al., 2005); and 4) a 453 bp probe of the HTS1 ORF located at the telomere-proximal side of ILV3. These probes were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA, using the oligonucleotides indicated in Table 2. These oligonucleotides were designed according to the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

3. Results

3.1. Kinetics of appearance of Sou+ colonies from CAF2 and rad52 strains

As shown in Table 3 (Expt. 1), when inoculated at a concentration of about 3000 cells per plate, CAF2 generated Sou+ colonies most of them developing in a period of three to four days following a 12 day incubation period, with a final yield of 15-25%. A similar pattern and yield was produced by the heterozygote (CaRAD52/Carad52Δ) and a reconstituted strain (TCR3.2.1)(Ciudad et al., 2004). On the other hand, for two rad52-ΔΔ strains plated at the same cell density (only TCR2.2 is shown) a significantly reduced yield (2.5 -5%) of Sou+ colonies was observed. In spite of its lower final yield, the time of appearance of these rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ colonies was earlier on average, and in fact between days 5 and 9, the Rad52- strain produced a larger number of colonies than any of the Rad52+ counterparts (Table 3). Three additional experiments, one of which is shown Table 3 (Expt.2), indicated that the bias towards the earlier generation and the lower final yield of sorbose-resistant strains in rad52-ΔΔ cells was highly reproducible. We found, however, some variability with regard to the exact period of maximum production of Sou+ (for instance, for CAF2, days 13-15th in expt. 1 and 10-12th day in expt. 2).

Table 3.

Daily appearance and final yield of Sou+ colonies from the indicated strains

| Straina | Total cells platedb (CFU) | Daily appearance of Sou+ colonies (days) c |

Sou+ CFUs in the indicated period (days) |

% Yield |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | (5-9) | (10-15) | (5-15) | |||

| Expt. 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| CAF2 | 3310 | 2 | 5± 1 | 5± 1 | 5± 1 | 6± 2 | 16± 3 | 24± 2 | 54± 14 | 234± 85 | 340± 90 | 42± 3 | 23 | 710 | 723 | 22 |

| TCR1 | 3120 | 5± 1 | 17± 4 | 16± 1 | 7± 1 | 6 | 17± 9 | 27± 4 | 63± 9 | 290± 98 | 288± 85 | 36± 11 | 51 | 721 | 772 | 24 |

| TCR2.2 | 3558 | 15± 5 | 24± 6 | 18± 2 | 13± 3 | 9± 3 | 14 ± 2 | 12± 1 | 3± 0 | 2± 0 | 0 | 0 | 79 | 31 | 110 | 3 |

| TCR3.2.1 | 3620 | 4± 1 | 11± 3 | 12± 2 | 10± 3 | 7± 3 | 21± 1 | 20± 3 | 76± 15 | 386± 24 | 353± 50 | 15± 2 | 44 | 871 | 915 | 25 |

| Expt. 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| CAF2 | 2256 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4±1 | 8±3 | 170±35 | 371±58 | 101±18 | 4±1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 646 | 660 | 29 |

| TCR2.2 | 3102 | 16±5 | 8±2 | 18±7 | 8±1 | 10±3 | 2±1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 3 | 63 | 2 |

Strains are indicated in Table 1.

Aliquots were plated on YEPD to determine the number of viab le cells added to sorbose plates

Results are means of CFU from two plates

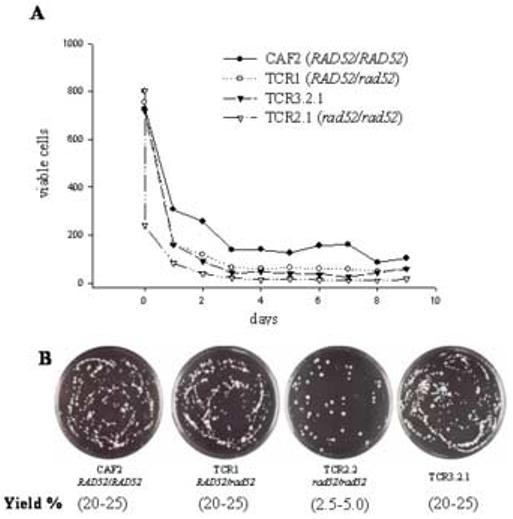

Viability of the four strains in the presence of sorbose was extremely low, but rad52-ΔΔ cells were particularly sensitive to the sugar (Fig. 1A). The fact that null cells die more quickly explains the lower final colony yield of these mutants. Once again, the relative timing of the appearance and final yield of the Sou+ colonies in this experiment followed essentially the pattern described in Table 3 (not shown).

Fig. 1.

(A) Viability of strains on sorbose plates. About 800 cells of each strain were plated in this experiment. For details see Materials and Methods. (B) Plates corresponding to an experiment similar to that indicated in Table 1 after 20 days of incubation on sorbose plates.

Colonies formed from rad52-ΔΔ cells were bigger on average (Fig. 1B), probably as a consequence of their earlier appearance. However, regardless of the nature of the parental Sou- strain (i.e., Rad52+ or Rad52- cells), almost all Sou+ colonies contained cells that were truly adapted to sorbose; not only did colonies increase in size with time, but more than 90% of cells readily formed colonies when transferred to new sorbose agar plates. Most Rad52+ cells formed visible colonies in four days, whereas a similar percentage of rad52-ΔΔ did so in five days. This observation is probably derived from the lower growth rate of rad52-ΔΔ cells as compared with the Rad52+ counterparts (Chauhan et al., 2005; Andaluz et al., 2006).

Since sorbose adaptation of C. albicans cells is mediated by genetic events, it is not surprising to find differences between Rad52+ and Rad52- strains. In rad52 mutants of S. cerevisiae, chromosome loss is increased as compared to wild type cells (Mortimer et al., 1981; Hiraoka et al., 2000; Yoshida et al., 2003). Since Rad52p plays a similar role in both organisms, one could expect an increase in the loss of chromosomes in rad52-ΔΔ strains of C. albicans, which would explain the earlier generation of Sou+ mutants. Furthermore, it is likely that loss of chromosomes in the presence of sorbose is not restricted to Chr5 but affects other chromosomes leading frequently to cell death [as described for the conversion of tetraploids into diploids (Bennet and Johnson, 2003)], which, in turn, would be responsible for the lower yield of Sou+. Indeed, rad52-ΔΔ strains of C. albicans exhibit a much higher frequency of spontaneous chromosome loss than the parental Rad52+ strain from which they were derived (manuscript in preparation). This propensity to lose chromosomes seems to be significantly increased in the presence of sorbose.

3.2. Analysis of the MTL locus in Sou+ strains

As mentioned above, it is well documented that the loss of one copy of Chr5 is a major mechanism of adaptation to sorbose in C. albicans strains 3153A and CAF2 (Janbon et al., 1998; 1999; Andaluz et al., 2002). In order to investigate whether the Sou+ cells from our experiments shared this feature, we analyzed the loss of heterozygosity at the MTL locus. As shown in Fig. 2A, parental CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ (lanes 1 and 5) were heterozygous for MTL since they carry both MTLa1 and MTLα1 genes. On the other hand, although most of the Sou+ derivatives were homozygous for MTL as shown for two of them derived from CAF2 (C-Sou+1, lane 2, and C-Sou+2, lane 3) and four derived from rad52-ΔΔ (r-Sou+1 to r-Sou+4, lanes 6-9 respectively), there was no absolute correlation between the Sou+ phenotype and homozygosity at the MTL locus. Three examples of this, one for CAF2 (C-Sou+3, lane 4) and two for rad52-ΔΔ r-Sou+5 and r-Sou+6, lanes 10 and 11 respectively) are shown in Fig. 2A. A screen of 43 Rad52+ Sou+ strains indicated that most of them (approximately 70%) were homozygous (2 a and 28 α), but a significant percentage (30%) were heterozygous for MTL (13 a/α). A similar screen of 97 Rad52- Sou+ strains yielded values of 83% (50% a and 33% α) and 17% respectively (Table 4). As expected, strains carrying MTLα1 also carried MTLα2 and cells lacking MTLα1 also lacked MTLα2 (not shown). In summary, most Sou+ cells are homozygous for the MTL locus but a significant percentage (30% for CAF2 and 17% for rad52-ΔΔ) are still heterozygous. Curiously, our results indicate a bias towards the generation of MTL α strains (28 out of 30) versus MTL a (2 out of 30) in the CAF2 MTL-homozygous derivatives. Recently, it has been reported that the size of the MRS influences the frequency of chromosome loss. For instance, with regard to Chr5, the copy with the largest MRS was preferentially loss (Lephart et al., 2005). We do not know whether this MRS-based bias operates in our case, since the size of MRS alleles of chromosome 5 from strain CAF2 has not been reported. A similar preference for the loss of the MTLa allele recently has been observed by Wu et al. (2005) during the spontaneous generation of sixteen MTL-homozygous offspring from four natural a/α strains. This may indicate that there are deleterious, not necessarily lethal, alleles in the a copy of Chr5 from CAF2. However, the distribution between a and α strains was 50% and 33% in the Sou+ derivatives of the rad52-ΔΔ strain. The same was true for CAI4, where MTL a- and MTLα-Sou+ strains were recovered at a similar frequency (Lephard et al., 2005). Therefore, it is likely that during the generation of strain CAI4 from CAF2, putative deleterious alleles have become homozygous and have conserved the homozygosity in the CA4-derived rad52-ΔΔ mutants.

Fig. 2. MTL analysis and karyotyping of Sou+ strains with chromosomal rearrangements.

A. PCR analysis of the MTL locus in representative Sou+ strains derived from CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ. Lanes correspond to parental CAF2 Sou- (lane 1); its Sou+ derivatives C-Sou+1 to C-Sou+3 (lane 2 to 4, respectively); parental rad52-ΔΔ Sou- (lane 5); and its derivatives r-Sou+1 to r-Sou+6 (lane 6 to 11 respectively); B and C. Analysis of the standard electrophoretic karyotypes (left) (Ba) or the electrokaryotypes under conditions that separate homologues of the shortest chromosomes (panel Ca) of the strains indicated in A, and corresponding Southern blots (right) using the indicated probes. Arrows indicate obvious extrachromosomal bands. Bottom: Diagram of chromosome 5, showing the approximated location of the several markers or probes used in this study. The centromere is indicated (Sanyal et al., 2004).

Table 4.

Distribution of the Sou+ strains with regard to the MTL locus

| MTLa | MTLα | MTLa/MTLα | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAF2 | 2 (4.6%) | 28 (65.1%) | 13 (30.2%) |

| rad52-ΔΔ (TCR2.2) | 47 (50%) | 32 (33%) | 16 (17%) |

3.3. Karyotypes and SNP analysis of Sou+ strains homozygous for the MTL locus

The lack of either MTL locus could result not only from the loss of the entire Chr5, but also from any deletion that includes that region. Conversely, the presence of both MTL loci does not guarantee the presence of two full copies of Chr5. A visual inspection of the karyotypes (Fig. 2Ba) of parental CAF2 (Sou-)(lane 1) and two Sou+ derived strains homozygous for the MTL locus (lanes 2-MTL a- and 3 -MTLα-) suggests that whereas the former carries two copies of Chr5, most of the latter seemed to have lost one copy of that chromosome. The same was true for parental rad52-ΔΔ (a/α)(lane 5) and four rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ strains homozygous for the MTL locus (two MTLa and two MTLα)(lanes 6-9). Quantification of the ethidium bromide signal using chromosome 2 as an internal standard confirmed these suspicions. The Chr5/Chr2 ratio was about 1 in both parental CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ Sou- strains but dropped to one half in all the MTL homozygous derivatives, with the exception of the strain r-Sou+2 (lane 7). An analysis of a SNP marker of Chr2 (SNP68) indicated that all the strains were heterozygous for that marker and yielded the same amount of each base at each polymorphic site (data not shown). Since the relative ethidium bromide signal of Chr2 looked normal, these results suggest that all the strains were in fact disomic for Chr2 and support our approach in determining the copy number of Chr5. In two rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ strains, an additional extracromosomal band was also observed (lanes 6 and 9 of Fig. 2Ba, and 2Ca, black arrows). Southern analysis of the electrophoretical karyotypes indicated that a probe of the SfiI 5I fragment (CDC1) only labelled Chr5 (Fig. 2Bc). Similarly, a probe of the SfiI 5M fragment (GCD11) only labelled Chr5 in all the MTL homozygous strains (Fig. 2Bb and 2Cb). None of these probes labelled any of the new chromosomal bands (Fig 2B and 2C, lanes 6 and 9), suggesting that they originated by a break of chromosomes other than Chr5. On the other hand, the relative intensity of the labelled band corresponding to Chr5 was consistent with the presence of two copies of this chromosome in both parental strains (Fig. 2Bb and 2Bc; lanes 1 and 5) and one copy in each of the MTL homozygous strains, again with the exception of strain r-Sou+2 (lane 7), suggesting that this strain likely had duplicated Chr5. Finally, in order to be sure that the homozygosity of the MTL locus extends to other regions of Chr5, we analyzed two intergenic regions of this chromosome located at both sides of the centromere known to be polymorphic in strain SC5314 because of the presence of several SNPs (Forche et al., 2004; A. Forche, personal communication; Sanyal et al., 2004): one in the left arm, SfiI fragment 5M, (SNP110 in contig 19-10198), and the other in right arm, SfiI fragment 5I (SNP118 in contig 19-10194)(Fig. 2, bottom). Both regions conserved the heterozygosities in parental Sou- CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ strains but became homozygous in the Sou+ derivatives that were homozygous for the MTL locus. Moreover, a-strains carried one allele and α strains the other allele (Table 5). Accordingly, in strains homozygous for the MTL locus, whose proportions were similar for CAF2 (70%) and rad52-ΔΔ (83%), most if not all Sou+ strains arise by chromosome loss.

Table 5.

Sequences of SNPs 110 and 118 in the indicated strains

| Sequence at the polymorphic sites |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| SNP110+* | SNP118+* | SNP68 | |

| CAF2. | YRY | RKRY | RWYRHYR |

| CAF2- a1 (C-Sou+1) | CGT | AGAC | RWYRHYR |

| CAF2-α1 (C-Sou+2) | TAC | GTGT | RWYRHYR |

| CAF2-aα (C-Sou+3) | YRY | RKRY | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ Sou- | YRY | RKRY | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ-a1 [r-Sou+(1-2)] | CGT | AGAC | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ-α1[r-Sou+(3-4)] | TAC | GTGT | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ-aα [r-Sou+5#] | YRY | GTGT | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ-aα [r-Sou+6#] | YRY | GTGT | RWYRHYR |

| rad52-ΔΔ-aα [r-Sou+(7-12)] | YRY | RKRY | RWYRHYR |

Y denotes C or T; R denotes A or G; K denotes G or T

Only the polymorphic sites are shown. The rest of the sequence agrees with that present in the Candida database.

These strains contain fragmented chromosomes and correspond to lanes 10 (Sou+5) and 11(Sou+6) of Fig. 2.

3.4. Karyotypes and SNP marker analysis of Sou+ rad52-Δ strains heterozygous for MTL but exhibiting chromosome fragmentation

The presence of both MTL loci in some Sou+ strains suggests the existence of at least one additional genetic alteration responsible for sorbose utilization. The electrophoretic karyotypes indicated the presence of at least two extrabands in strain r-Sou+5 (Fig. 2Ca, lane 10, white arrows) and one extraband in strain r-Sou+6(Fig. 2Ba). A Southern blot using the GCD11 probe labelled Chr5 (1.190 kb) plus another extrachromosomal band slightly smaller than Chr7 (950 kb) in strain r-Sou+5 (Fig. 2Bb and 2Cb, lanes 10, lower white arrows). Similarly, the same probe labelled Chr5 and the extraband of strain r-Sou+6 but, in this case, the missing fragment was significantly larger (Fig. 2Bb, lane 11; this band was lost in the gel of Fig 2Cb, due to its small size), By contrast, the CDC1 probe did not label any of the extrachromosomal bands (Fig. 2Bc), and the same was true when the karyotypes were probed with ILV3, a subtelomeric ORF telomere proximal to CDC1, and HTS11, the closest ORF to the right telomere (apart from CTA2 that is common to fourteen out of the sixteen telomeres in C. albicans). In agreement with this, SNP analysis indicated that both strains were heterozygous for SNP110 (5M) but homozygous for SNP118 (5I)(Table 5). The presence of markers from both arms (SNP110 and GCD11) indicates that the fragments retain the centromere. However, the absence of three subtelomeric markers of the SfiI fragment 5I (CDC1, ILV3, and HTS1) as well as the homozygosity at a polymorphic region located in the right arm (SNP118) suggest that a fragment in the neighbourhood of the right telomere had been lost (acentric fragment). Furthermore, from the sequence found in SNP118, it follows that in both strains the deletion occurred in the homologue carrying the MTL a allele (Table 5). Whether specific deletions in this region of the Chr5 homologue carrying MTL a facilitate sorbose assimilation more than deletions of its counterpart carrying MTLα will require statistical analysis. Regardless of the significance of this bias, our results suggest that the subtelomeric region of the 5I fragment is a likely candidate to carry one or more ORFs with special relevance to the mechanism of adaptation to sorbose. From the size of the extrabands derived from Chr5 (lane 10 of Fig. 2Bb and 2Cb, and lane 11 from Fig 2Bb), it follows that the lost fragment had a size of about 250 kb in strain r-Sou+5 (lane 10) and close to the size of the whole right arm of that chromosome in the strain r-Sou+6 (lane 11). This result agrees with and further supports the recent finding that a terminal deletion of Chr5 that eliminated 356 kb of the right arm caused a Sou+ phenotype. Within this stretch, a 209 kb fragment was shown to contain at least five regions which are critical for the Sou+ phenotype since deletion of one copy of certain combinations of the regions had the same effect than the loss of the entire chromosome (Kabir et al., 2005). While we have not detected this kind of arrangement of Chr5 in 15 Sou+ mutants derived from CAF2, it might occur, although rarely, in Rad52+ strains. In fact, Rustchenko (2006) has pointed out that 2 out of 59 Sou+ mutants derived from the wild type strain 3153A carry a large deletion in the right arm of chromosome 5.

We have not identified the nature of the genetic alteration responsible for the shortening of one of the Chr5 homologues in some Sou+ strains. Two possibilities exist: chromosome fragmentation followed by healing or internal deletion. We favour chromosome fragmentation followed by the addition of a telomere because of both the homozygosity at SNP118 and the absence of CDC1, ILV3 and, especially, HTS1 (the closest ORF to the right telomere, except CTA2) (Fig. 2, bottom) in both extra bands derived from Chr5. We cannot rule out that subtelomeric regions are prone to be involved in large deletions in C. albicans. However, it is unlikely that these processes, which usually rely in recombination between direct repeats, occur or are frequent in the absence of Rad52 (Paques and Haber, 1999).

It should be noted that chromosomal separation of the shorter chromosomes indicated the presence of an additional extraband of slightly lower size than Chr5 (Fig. 2C a, lane 10, upper white arrow; see below) in strain Sor5-rad52. However, neither the GCD11 nor the CDC1 probes hybridized to that band (Fig. 2Cb, lane 10), indicating that is unrelated to Chr5.

3.5. Karyotypes and SNP analysis of the Sou+ strains heterozygous for MTL carrying two, apparently normal, copies of Chr5

In the case of the Sou+ strain derived from CAF2 (Fig 2Ba, lane 4) there are apparently two copies of Chr 5 (see above), but the intensity of Chr4 also increased, suggesting the presence of at least three copies of this chromosome and accordingly of SOU1. Although this situation has not been described before, it would fit in the proposal that SOU1 expression is down regulated by a repressor present in Chr5 (Janbon et al., 1998; Greenberg et al., 2005). The expression of SOU1 is insufficient for growth on sorbose normally but could become sufficient from monosomy of Chr 5 or trisomy of Chr4. However, a restriction analysis of a heterozygous locus (RBT7) located in that chromosome indicated that the relative amount of the restriction fragments yielded by this strain was indistinguishable from that yielded by both parental CAF2 and rad52-ΔΔ, as well as by the rest of the Sou+ derivatives of either strain analyzed (Fig. 3A). These data suggest that either both homologues of chromosome 4 had duplicated or the increase in the intensity of that chromosome was due to the co-migration of a fragment derived from a larger chromosome. Hybridization of the electrophoretical karyotypes to a probe of chromosome 4 (RAD17) supported the first possibility since the intensity of the label was significantly higher than that found for the rest of the strains including CAF2 (Fig. 3Bb, lanes 3 and 4, compare the intensities of the label in Chr4 with those of the label in Chr5 in Fig. 2Bb or 2Bc).

Fig. 3. Analysis of copy number and heterozygosities of chromosome 4 in selected Sou+ strains.

A) RBT7 analysis of the indicated strains. The control used is a homozygous strain for RBT7 isolated in our laboratory. B) Southern blot analysis of the RAD17 locus. Karyotypes are the same of Fig. 2Ba. Lanes are as in Fig. 2.

In an effort to identify additional causes for the Sou+ phenotype of a/α strains displaying apparently regular karyotypic profiles, we obtained and analyzed new strains with these characteristics derived from either CAF2 or rad52-ΔΔ. As shown in Fig. 4A, the karyotypes of the new strains did not show significant alterations, and probes derived from Chr5 fragments 5I (CDC1) and 5M (GCD11) only labelled Chr5 (Fig. 4B). Electrokaryotypes intended to separate derivatives of Chr5 carrying small deletions (Legrand et al., 2004; Selmecki et al., 2005), did not indicate alterations in this chromosome either (not shown). As expected, both homologues of Chr6 and Chr7 could be distinguished under these conditions. Also, both homologues of Chr6 became closer in the rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ derivatives (not shown), but this also occurred in parental rad52-ΔΔ Sou- strains (see Fig. 2Ca).

Fig. 4. Karyotypes of selected Sou+ MTL a/α strains lacking obvious chromosomal alterations.

A) Standard electrophoretical karyotypes of new a/α Sou+ strains derived from CAF2 (C-Sou+4-6, lanes 1-3) or rad52-ΔΔ (r-Sou+7-12. lanes 4-9). B and C. Southern blot analysis of the karyotypes with the indicated probes of Chr5 (B) or Chr1 (C).

In order to investigate if the Sou+ phenotype of these strains could result from LOH in a region of Chr5, we analyzed the SNP118 marker (which had been deleted in one of the truncated copies of Chr5 of the rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ strains 5 and 6 shown in Fig. 2), in two additional strains (rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ 11 and 12 of Fig. 4, lanes 8 and 9). In both strains, this marker conserved the heterozygosities present in the parental CAF2. Accordingly, it is likely that, as shown before for other rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ strains (Fig. 2), the additional strains also carry truncations/translocations in other chromosomes. Supporting this possibility, a Southern blot of the karyotypes probed with a fragment of ACT1, located in Chr1, labelled not only this chromosome but also a truncated derivative that co-migrated with Chr3 in strain r-Sou+7 (Fig. 4C, lane 4).

4. Conclusions

rad52-ΔΔ cells of C. albicans produce Sou+ mutants earlier than the parental strain CAF2 but the total yield is significantly lower. A likely possibility is that this behaviour derives from an increased propensity of rad52-ΔΔ strains to lose chromosomes indiscriminately.

Fragmentation of chromosomes is quite frequent in rad52-ΔΔ strains of C. albicans when plated on sorbose plates, since four out of six rad52-ΔΔ Sou+ derivatives analyzed in some detail (Fig. 2, lanes 6, 9 10, and 11) showed at least one extrachromosomal band. By contrast, we could not detect obvious signs of fragmentation in 15 independent Sou+ strains derived from CAF2 (not shown; examples are given in Figs 2 and 4). In two cases, in which fragmentation caused the loss of the fragment ≥ 250 kb close to the right telomere, cells grew on sorbose. This supports previous findings on the importance of this region in the adaptation to sorbose (Kabir et al., 2005). As suggested by the analysis of two chromosomal fragments derived from Chr5, each in a different Sou+ strain, broken chromosomes seem to be stabilized by the addition of telomere.

In addition to alterations in the number or the length of one copy of chromosome 5, there exist alternative mechanisms of adaptation to sorbose which are not infrequent in the SC5414 lineage.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Public Health Service grant, NIH-NIAID 1 R01 AI51949 to R.C. and G.L. and a grant from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias PI042599 to E.A. We thank Bebe Magee for providing the markers of the SfiI fragments 5I and 5M, and Anja Forche and Judith Berman for providing primer sequences for SNP markers amplification prior to publication, as well as information on the RBT7 RFLP sites. Belén Hermosa was partially supported by grant 2PR03A044 from Junta de Extremadura to E.A. JGR is the recipient of a fellowship from the NIH-NIAID 1 R01 AI51949 grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andaluz E, Ciudad T, Gómez-Raja J, Calderone R, Larriba G. Rad52 depletion in Candida albicans triggers both the DNA-damage checkpoint and filamentation accompanied but independent of expression of hypha specific genes. Mol. Microbiology. 2006;59:1452–1472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andaluz E, Ciudad T, Larriba G. An evaluation of the role of LIG4 in genomic instability and adaptive mutagenesis in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Research. 2002;2:341–349. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(02)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. EMBO J. 2003;22:2505–2515. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RJ, Miller MG, Chua PR, Maxon ME, Jonhson AD. Nuc lear fusion occurs during mating in Candida albicans and is dependent on the KAR3 gene. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1046–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan N, Ciudad T, Rodríguez-Alejandre A, Larriba G, Calderone R, Andaluz E. Virulence and karyotype analyses of rad52 mutants of Candida albicans: regeneration of a truncated chromosome of a reintegrant strain (rad52/RAD52) in the host. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:8069–8078. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8069-8078.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad T, Andaluz E, Steinberg-Neifach O, Lue N, Gow N, Calderone R, Larriba G. Homologous recombination in Candida albicans: role of CaRad52p in DNA repair, integration of linear DNA fragments and telomere length. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1177–1194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forche A, Magee PT, Magee BB, May G. Genome-wide single- nucleotide polymorphism map of Candida albicans. Eukaryotic Cell. 2004;3:705–714. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.3.705-714.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forche A, May G, Magee PT. Demonstration of loss of heterozygosity by single-nuc leotide polymorphism microarray analysis and alterations in strain morphology in Candida albicans strains during infection. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:156–165. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.1.156-165.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotid ine-5‘-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genetics. 1984;198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JR, Price NP, Oliver RP, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Candida albicans SOU1 encodes a sorbose reductase required for L-sorbose utilization. Yeast. 2005;22:957–969. doi: 10.1002/yea.1282. Erratum in: Yeast 22,1171.

- Hiraoka M, Watanabe K, Umezu K, Maki H. Spontaneous loss of heterozygosity in diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;156:1531–1548. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton NJ, Goodwin TJD, Buttler MI, Poulter RTM. An active retrotransposon in Candida albicans. Nucleic Acid Res. 2001;29:4014–4024. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.19.4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, Johnson AD. Identification of a mating type-like locus in the asexual pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Science. 1999;285:1271–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull CM, Raisner RM, Johnson AD. Evidence for mating of the asexual yeast Candida albicans. Science. 2000;289:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Monosomy of a specific chromosome determines L-sorbose utilization: a novel regulatory mechanism in Candida albicans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:5150–5155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbon G, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Appearance and properties of L-sorbose-utilizing mutants of Candida albicans obtained on a selective plate. Genetics. 1999;153:653–664. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir MA, Ahmad A, Greenberg IR, Wang Y-K, Rustchenko E. Loss and gain of chromosome 5 controls growth of Candida albicans on sorbose due to disperse redundant negative regulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:12147–12152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505625102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein HL. Spontaneous chromosome loss in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is suppressed by DNA damage checkpoint functions. Genetics. 2001;159:501–1509. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larriba G.San Blas G, Calderone R.Genome instability, recombination, and adaptation in Candida albicans Pathogenic Fungi: host interactions and emerging strategies for control 2004. Chapter 8 285–334.Horizon Press; UK [Google Scholar]

- Legrand M, Lephart P, Forche A, Magee PT, Magee BB. Homozygosity at the MTL locus in clinical strains of Candida albicans is correlated with karyotypic rearrangements. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:1451–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lephart PR, Chibana H, Magee PT. Effect of the major repeat sequence on chromosome loss in Candida albicans. Eukaryotic Cell. 2005;4:733–741. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.4.733-741.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee PT, Chibana H.Calderone RA.The genomes of Candida albicans and other Candida species Candida and Candidiasis 2002293–304.American Society for Microbiology Press, Inc. Chapter 21 Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Magee BB, Magee PT. Induction of mating in Candida albicans by construction of MTL a and MTL alpha strains. Science. 2000;289:310–313. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5477.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer RK, Contopoulou R, Schild D. Mitotic chromosome loss in a radiation-sensitive strain of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:5778–5782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.9.5778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olaiya AF, Sogin SJ. Ploidy determination of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1979;140:1043–1049. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.1043-1049.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepnikhatka V, Fischer FJ, Niimi M, Baker RA, Cannon RD, Wang YK, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Specific chromosome alterations in fluconazole-resistant mutants of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:4041–4049. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.13.4041-4049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad TR, Stevens DA, Pfaller MA, White TC. Homozygosity at the Candida albicans MTL locus associated with azole resistance. Microbiology. 2002;148:1061–1072. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-4-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustchenko E. Chromosome instability in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00150.x. (in press).

- Rustchenko E, Howard DH, Sherman F. Chromosomal alterations of Candida albicans are associated with the gain and loss of assimilating functions. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:3231–3241. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3231-3241.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustchenko E, Sherman F. Genetic instability in Candida albicans. In: Howard DH, editor. Pathogenic fungi in humans and animals. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 723–776. [Google Scholar]

- Rustchenko-Bulgac EP, Sherman F, Hicks JB. Chromosomal rearrangements associated with morphological mutants provide a means for genetic variation of Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:1276–1283. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1276-1283.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal K, Baum M, Carbon J. Centromeric DNA sequences in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans are all different and unique. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:11374–11379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404318101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmecki A, Bergmann S, Berman J. Comparative genome hybridization reveals widespread aneuploidy in Candida albicans laboratory strains. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55:1553–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selmecki A, Forche A, Berman J. Aneuploidy and isochromosome formation in drug-resistant Candida albicans. Science. 2006;313:367–370. doi: 10.1126/science.1128242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavanti A, Gow NAR, Maiden MCJ, Odds FC, Shaw DJ. Genetic evidence for recombination in Candida albicans based in haplotype analysis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2004;41:553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YK, Das B, Huber DH, Wellington M, Kabir MA, Sherman F, Rustchenko E. Role of the 14-3-3 protein on carbon metabolism of the pathogeneic yeast Candida albicans. Yeast. 2004;21:685–702. doi: 10.1002/yea.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Pujol C, Lockhart SR, Soll D. Chromosome loss followed by duplication is the major mechanism of spontaneous mating-type homozygosis in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2005;169:1311–1327. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.033167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida J, Umezu K, Maki H. Positive and negative roles of homologous recombination in the maintenance of genome stability in Saccharomyces cervisiae. Genetics. 2003;164:31–46. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]