Abstract

A key issue in the debate over the initial colonization of North America is whether there are spatial gradients in the distribution of the Clovis-age occupations across the continent. Such gradients would help indicate the timing, speed, and direction of the colonization process. In their recent reanalysis of Clovis-age radiocarbon dates, Waters and Stafford [Waters MR, Stafford TW, Jr (2007) Science 315:1122–1126] report that they find no spatial patterning. Furthermore, they suggest that the brevity of the Clovis time period indicates that the Clovis culture represents the diffusion of a technology across a preexisting pre-Clovis population rather than a population expansion. In this article, we focus on two questions. First, we ask whether there is spatial patterning to the timing of Clovis-age occupations and, second, whether the observed speed of colonization is consistent with demic processes. With time-delayed wave-of-advance models, we use the radiocarbon record to test several alternative colonization hypotheses. We find clear spatial gradients in the distribution of these dates across North America, which indicate a rapid wave of advance originating from the north. We show that the high velocity of this wave can be accounted for by a combination of demographic processes, habitat preferences, and mobility biases across complex landscapes. Our results suggest that the Clovis-age archaeological record represents a rapid demic colonization event originating from the north.

Keywords: Early Paleoindian, wave of advance, landscape complexity, hunter-gatherers, Late Pleistocene

In this article, we consider five alternative hypotheses that have been proposed to account for the initial early Paleoindian occupation of North America. The first hypothesis is the traditional model, which states that Clovis peoples migrated into unglaciated North America from Beringia via an ice-free corridor between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets (1). Research suggests that an ice-free corridor would have been open and available for human passage by 12,000 years ago (1), although the habitability of the corridor is still a matter of debate (2). However, recently, there has been renewed interest in alternative hypotheses. A second hypothesis is that Clovis peoples migrated along the coast of Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington State (2, 3). This model, usually referred to as the Northwest Coast model, suggests that maritime-adapted groups using boats moved along the ice-free western coast and sometime later moved east into the interior of the continent. A third hypothesis, which has been raised recently is that the initial colonists could have rapidly skirted the western coast of North America and established their first substantial occupations in South America (4). In this hypothesis, colonists would then have moved north through the Isthmus of Panama colonizing North America from the south. A fourth hypothesis is that North America was colonized by Solutrean people who had traveled along the edge of an “ice bridge” between Europe and North America (5) so that the initial colonization occurred from the east. This hypothesis is driven by suggested similarities between Clovis and pre-Clovis technology on the one hand and Solutrean technology on the other, which some take to indicate an historical connection (5). A fifth hypothesis, as proposed by Waters and Stafford (6), is that Clovis technology may have been a technological innovation that spread via cultural transmission through an established pre-Clovis population, which had colonized North America sometime earlier in the Pleistocene before the Clovis phenomenon.

We test these five models by analyzing the spatial distribution of Clovis and Clovis-aged radiocarbon dates across North America. We include the earliest available Clovis or Clovis-age dates from different regions of North America with the assumption that they reflect meaningful temporal and spatial variation in the initial colonization process. We located the potential origin of a colonizing wave at six locations, four reflecting the external origins of the alternative colonization models (north for the traditional or ice-free corridor model, east for the Solutrean model, south for the Isthmus of Panama, and west for the Northwest Coast model), and two reflecting pre-Clovis origins. For the northern origin, we chose Edmonton, Alberta, following the assumed location of the southern mouth of the ice-free corridor (7, 8). For the east, we chose Richmond, VA, a location roughly halfway down the east coast of North America. For the southern origin, we chose Corpus Christi, TX, reflecting a potential route north through Central America (4), and for the western origin, we chose Ventura, CA, a location about halfway down the west coast of North America and across from the Channel Islands, where late Pleistocene human remains and evidence for a contemporaneous maritime-based subsistence economy have been recovered (9, 10). Although each wave is centered on a particular location, given the width of the wavefronts used, and the small sample size of available radiocarbon dates, our results are robust to reasonable changes in origin. For the pre-Clovis origin model, we centered the colonizing wave on Meadowcroft Rockshelter (11) in Pennsylvania, and Cactus Hill (12) in Virginia, two of the earliest, and most prominent pre-Clovis candidates in North America.

Time-Delayed Wave of Advance Model.

To model the wave of advance, we follow procedures outlined by Fort and colleagues (13–18) in their recent studies of other human prehistoric expansions. The simple wave of advance model combines a logistic population growth term with Fickian diffusion, which describes the spread of the population in two spatial dimensions. The resulting equation is termed the Fisher equation:

where γ is the maximum potential growth rate, N is population size or density, K is the carrying capacity of the local environment, D is the diffusion coefficient (in km yr−1), and ▿ is the Laplacian operator describing the diffusion of the population N in two dimensions.

The diffusion coefficient measures the lifetime dispersal of an individual, measured by the average distance between location of birth and first reproduction. This measure, the mean squared displacement of an individual, is then adjusted by random dispersal in two dimensions, and generation time T, giving the diffusion coefficient D = λ2/4T, where λ2 is the mean square displacement. The well known solution to Eq. 1 produces traveling waves of colonists radiating out in concentric circles from an initial point of origin. The velocity v of this wavefront of colonists is given by

Note that the velocity is simply a function of the population growth rate γ and the diffusion rate D and independent of population size N or carrying capacity K. Although widely used in the analysis of spatial movement, the Fisher equation incorporates some biologically and anthropologically unrealistic assumptions (19), perhaps most importantly, that individual dispersal begins at birth, and so dispersal is continuous through life. However, human dispersal is best modeled discretely because there is generally a time delay between birth and dispersal, related to rates of human growth and development. This time delay reflects the situation that as a hunter–gatherer residential group establishes a new home range during the process of colonization, there is a time delay before the next generation expands into the adjacent landscape. Fort and colleagues (13, 14, 19) derived a model to account for such generational time delays in the diffusion process. They show the velocity of the time-delayed traveling wave is then

|

The velocity of the wavefront is thus reduced as a function of the generational time delay T. Note that in cases where there is no time delay (T = 0), Eq. 3 reduces to Eq. 2. The expected velocity of a hunter–gatherer population expansion can then be estimated by parameterizing Eq. 3 with ethnographic data on maximum population growth rates γ, mean generation times T, and measures of individual lifetime dispersal D.

Parameter Estimation.

We estimate these parameters using published data from refs. 20 and 21. For natural fertility populations, age at first birth, a common measure of mean generation time T is ≈20 years, and maximum annual population growth rates γ is ≈0.04 (20). Measures of lifetime dispersal in modern hunter–gatherers are more difficult to quantify. By using hunter–gatherer mating distance data (21), mean individual dispersal within populations can be conservatively estimated to be up to 3,000 km2 per generation, although the upper range for a recorded marriage distance gives a mean squared distance of nearly 21,000 km2. Although these data are not ideal measures of dispersal, where the data are available, marriage distance has been shown to correlate both strongly and positively with generational dispersal (22). Therefore, we use 3,000 km2 as a conservative measure of lifetime dispersal, giving D = 37.5 km2. These demographic measures are conservative because these data originate from societies near demographic equilibrium, with neighboring populations, a situation far from representative of a rapidly growing, late Pleistocene hunter–gatherer population expanding into an open landscape. Combining these parameters with Eq. 3, the expected velocity of this wave is then ≈ν = 1.77 km per year.

Data.

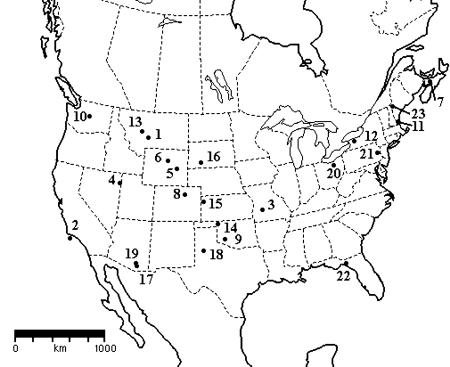

We used radiocarbon dates or averaged dates from 23 sites (see Table 1, Fig. 1, and Methods). Seventeen of the dates are those identified by Waters and Stafford (6) as either reliable Clovis or Clovis-aged dates. The other six are dates from other Clovis or Clovis-age sites that occur in similar contexts but were not considered in their analyses (see Methods for details). Five of these sites (Debert, Vail, Casper, Hiscock, and Big Eddy) can be considered Clovis sites because of the presence of Clovis-like fluted points. Hedden lacks fluted points, but has a subsurface assemblage dating to the same period as other regional Clovis-age sites (Table 1). The majority of the additional dates (n = 5) are from early Paleoindian sites located in eastern North America, which are widely considered to represent the earliest dated late-Pleistocene occupations of the east (23). This sample size is admittedly extremely small, but we are limited by the rarity of well dated Clovis-age sites (6). All radiocarbon dates used in our analyses (Table 1) were calibrated by using the Intcal04.14 curve (24) in Calib 5.0.

Table 1.

Radiocarbon and calibrated dates used in Fig. 1

| Number | Site | Date, 14C yr B.P. | Error (±1 σ) | Calibrated date B.P. | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anzick | 11,040 | 35 | 12,948 | 6 |

| 2 | Arlington Springs | 10,960 | 80 | 12,901.5 | 6 |

| 3 | Big Eddy | 10,832 | 58 | 12,842.5 | 46 |

| 4 | Bonneville Estates | 11,010 | 40 | 12,922.5 | 6 |

| 5 | Casper | 11,190 | 50 | 13,106 | 45 |

| 6 | Colby | 10,870 | 20 | 12,855.5 | 6 |

| 7 | Debert | 10,590 | 50 | 12,429 | 48 |

| 8 | Dent | 10,990 | 25 | 12,910.5 | 6 |

| 9 | Domebo | 10,960 | 30 | 12,895 | 6 |

| 10 | East Wenatchee | 11,125 | 130 | 13,025 | 6 |

| 11 | Hedden | 10,550 | 43 | 12,437.5 | 49, 50 |

| 12 | Hiscock | 10,795 | 39 | 12,828.5 | 51 |

| 13 | Indian Creek | 10,980 | 110 | 12,925 | 6 |

| 14 | Jake Bluff | 10,765 | 25 | 12,817.5 | 6 |

| 15 | Kanorado | 10,980 | 40 | 12,906.5 | 6 |

| 16 | Lange-Ferguson | 11,080 | 40 | 12,994 | 6 |

| 17 | Lehner | 10,950 | 40 | 12,891 | 6 |

| 18 | Lubbock Lake | 11,100 | 60 | 13,010 | 6 |

| 19 | Murray Springs | 10,885 | 50 | 12,862.5 | 6 |

| 20 | Paleo Crossing | 10,980 | 75 | 12,912.5 | 6 |

| 21 | Shawnee-Minisink | 10,935 | 15 | 12,883 | 6 |

| 22 | Sloth Hole | 11,050 | 50 | 12,969 | 6 |

| 23 | Vail | 10,530 | 103 | 12,255 | 52 |

Fig. 1.

Map showing the location of Early Paleoindian sites mentioned in text. Numbers correspond to those found in Table 1.

Statistical Approach.

To represent the expanding waves for each analysis, we measured the distance of each site from the wave's point of origin using great-circle arcs (in kilometers). To establish the earliest occupations per region, the earliest observations per bin were regressed against the dependent variable. Following methods outlined by Fort and colleagues (15–17, 19, 20), concentric bins were set at a consistent width (450 km) radiating out from each wave origin, and the earliest dated site within each bin was regressed by its distance from origin (see Methods for details). To evaluate the best-fit model, we calculated the correlation coefficient (r) for each test. The origin with the highest correlation coefficient is therefore the most likely point of origin (13, 14, 18). Similar methods have been used successfully in understanding colonization processes in other regions throughout prehistory (13–15, 17, 18). Here, we do not attempt to differentiate between demic and cultural diffusion models directly, because both types of model can be constructed to predict the same trajectories through time (25). Rather, similar to other researchers, we suggest that if a model can predict a demic diffusion, given realistic demographic and ethnographic parameters, then the hypothesis of demic diffusion has not been falsified until a cultural diffusion model could be shown to yield similar, or more accurate results (13, 14, 16, 18, 25).

Following Fort's methods, we estimate the velocity v of the wavefront as the inverse slope of the linear regression of time (calibrated dates) by distance (kilometers from origin). Because there is likely much more error in the measurement of time than in the measurement of distance, time is placed along the y axis and distance along the x axis. We also estimate the slope of distance by time because of possible errors in the measurement of distance. Simulations show that Fort's inverse-regression method tends to overestimate the slope when dealing with small sample sizes (data not shown), so we use randomization methods (10,000 iterations) to estimate the slope and significance of the second regression method. Further, we suggest that randomization statistics are appropriate here, because we are interested in testing both whether the pattern is significantly different from random rather than from an a priori distribution, which may or may not be normal, and whether the slope and correlations are negative, not simply statistically significant. We report the results of both methods.

Results

Best-Fit Model.

Our data show clear spatial gradients in the distribution of earliest Paleoindian occupation dates (Fig. 2). Not only was the northern origin model the model with the highest correlation coefficient (r = −0.73), but it was also the only statistically significant model (P = 0.008). Importantly, the only other wave near statistical significance was the western origin model (Fig. 2). It is interesting that in Fig. 2, each plot clearly reflects a general west-to-east trend in radiocarbon dates as shown by the dashed lines (linear regressions of the entire data sets), consistent with recent findings based on the cladistic analysis of Clovis projectile point morphometrics (26). The plot of all dates used in the analysis by distance from the northern origin is also highly significant (r = −0.59, P = 0.001, n = 23), suggesting that the spatial gradients of earliest occupation dates we report here are also evident in the average timing of the Clovis occupation across the continent.

Fig. 2.

Bivariate plots of the wave of advance analysis for each of the six potential origins. Filled circles are the earliest dates per 450-km bin. Open circles are the raw data (all 23 dates). Solid lines are regressions through the binned data, and dashed lines are regressions through the raw data. The correlation coefficients and P values refer to the solid lines.

The consistency of the west-to-east gradient in the ages of radiocarbon dates suggests that, despite the small sample size, these results are robust. In other words, there would need to be a consistent and fundamental change to the dating of early Clovis-age occupations both in the south and east to alter the findings we present here. Further, although the significance of the slope of the northern origin model is influenced by the relatively young date of the furthest bin (black circle to the furthest right in Fig. 2, upper left), excluding this data point does not change our results, because the slope remains significant (P = 0.034).

Slope.

The estimated velocity of the wavefront by using Fort's inverse regression technique was ν = 7.56 km per year and with the resampling method was ν = 5.13 km per year [1.89–14.14, 95% confidence limits (CLs)]. The confidence limits are too wide to provide much further constraints on the velocity. A possible reason for their width, aside from the small sample size, is that the wave velocity shown in the upper right graph in Fig. 2 begins very rapidly and decreases dramatically as the continent fills. Indeed, the correlation coefficient is improved by fitting the northern-origin model with a quadratic model (r = −0.82), reflecting this trend. We discuss this pattern further below.

Intercept.

The intercept of the regression equation predicts that Clovis colonists arrived at the mouth of the ice-free corridor ≈13,378 cal B.P. (12,896–13,867, 95% CLs) or, using the uncalibrated data, 11,342 14C B.P. (11,114–11,607, 95% CLs).

Discussion

Our results provide clear, quantitative evidence of a colonizing wavefront of early Paleoindians originating from the north. This wavefront moved rapidly to the south and east, traveling considerably faster than predicted from ethnographic data and faster than other recorded hunter–gatherer expansions into previously unoccupied land masses (17, 27, 28), although at a speed that is not, in itself, unprecedented (29, 30). Although this result does not discount the possible presence of a pre-Clovis population within North America, the speed of the wavefront suggests that any preexisting human populations offered little demographic, ecological, or territorial competition to the advancing front of colonists, and the available data suggest these populations were not the source of the subsequent Clovis culture.

Both the rapidity with which the Clovis culture appeared over the continent and the general trajectory of the colonization process have been noted several times before. In their classic model, Kelly and Todd (31) suggested that the speed of colonization was driven by high rates of residential mobility, because of the large foraging areas required of a primarily carnivorous diet (32). Reasoning from optimal foraging theory, they suggested that colonizing hunter–gatherers, with a northern latitude preadaptation (27), would have maximized return rates by focusing on widely available, predictable, high-return resources, in particular, mammalian megafauna. Because these prey species likely occurred at low densities, local prey would have been depleted quickly, causing foragers to expand into adjacent open regions. Because of their specialized foraging niche, home ranges would have been both very large and have had very low effective carrying capacities, resulting in a fast moving, shallow wavefront (33).

This model receives support from recent theoretical and empirical ecological research (34, 35), which shows that across species, optimal search strategies, and hence patch residence times, are influenced heavily not only by environmental productivity, but also by the regeneration rates of key prey species. In patches where prey regeneration rates are fast, foragers can reuse habitats regularly because of the rapid restocking of prey, whereas in patches where prey regeneration rates are long to infinite (i.e., where foraging causes local extirpation of prey) optimal search strategies become linear (34, 35), leading to high levels of mobility and the utilization of large foraging areas. Another, although not necessarily mutually exclusive, hypothesis suggests that colonizing populations followed least-cost pathways into the lower continent, where movement occurred rapidly either through favorable corridors, such as river drainages, or across areas of relatively homogenous topography (4, 27). These models predict that colonization would have bypassed, or traveled quickly across landscapes that were unfavorable because of topography and/or ecological productivity.

These models have obvious implications for regional variation in late Pleistocene foraging strategies. On the Plains and in the Southwest, where the archaeological record shows Clovis foragers targeted mammalian megafauna, diffusion rates would have been fast. In these regions, initial foraging return rates would have been high but regeneration rates of megafaunal prey would have been very slow [perhaps infinite (7, 8, 36)] because of low reproductive rates, leading to large home ranges and the rapid geographic expansion of human populations (sensu 31). Similarly, Clovis colonists would have moved rapidly through large river systems (4), such as the Missouri and Mississippi drainages, leading to an initially rapid rate of colonization through the midcontinent, which would have then slowed dramatically as diet breadths broadened with the increased biodiversity of the eastern forests (27, 37), and as prey size, abundance, and availability changed (38).

We suggest that these ideas are consistent with recent developments in understanding the movement of colonizing wavefronts across heterogeneous landscapes. Campos, Mendez, and Fort (39) analyzed the effects of diffusion across complex surfaces to understand the rapid rate of expansion (>13 km per year) of European populations across North America in the 17th to 19th centuries (40) where colonization was known to be biased toward key landscape features, particularly river valleys. They derived an analytical expression for the velocity of a traveling wave moving across complex, or fractal, surfaces:

which, combined with the time-delay adjustment in Eq. 3, gives

|

where dmin is the minimum dimension of the landscape, dw is the basic dimension of movement (two dimensions in this case), and μ = dmindw/(dmin + dw). The important parameter here to note is μ, which essentially measures the extent to which the population saturates the area behind the advancing wavefront (41). When μ = 2, the expanding population saturates 100% of the landscape behind the wavefront, or occupies proportion P = 1 of the landscape, where P = μ/dw, which would be the case if the colonizing population had no specific niche preferences and used all landscapes with equal probability.

However, as outlined above, an expanding, colonizing population of hunter–gatherers would have favored certain habitat types based on behavioral and technological adaptations, preferred foraging niches, prey types, and the mobility costs of different landscapes (4, 27). Thus, it is more than likely that for the Clovis colonists μ < 2, meaning that the population uses less than the full two dimensions of the landscape, with 1 − P proportion of the landscape unoccupied, causing the wavefront to advance at an increased velocity (see Fig. 3). Solving for μ when ν ≈ 5–8 (the observed velocity) gives μ ≈ 1.3–1.6, suggesting that Clovis colonists need to have used only ≈2/3 to 3/4 of the available landscape in order for the colonizing wave to have traveled at the velocity we observe in our data (Fig. 3 Upper). This finding is in qualitative agreement with the early Paleoindian archaeological record, which suggests that Clovis-age sites are found commonly in high-productivity areas, such as river basins as well as prime hunting areas (27). In addition, recent research shows that, indeed, ethnographic hunter–gatherers use landscapes in complex ways, which are reflected in nonlinearities in space use (42), residential mobility (43), and social network structure (44).

Fig. 3.

Functions describing the wave front velocity in terms of the diffusion coefficient and landscape complexity. (Upper) Wave velocity v as a function of the diffusion coefficient D for data used in the analysis. The horizontal dotted lines indicate the approximate upper and lower bounds for the observed velocity of the Clovis wavefront. The vertical dot–dash–dot line gives the approximate diffusion coefficient based on ethnographic data. The expected velocity from the simple time-delayed model (solid line) falls considerably short of the archaeologically observed velocity. The upper and lower curves based on Eq. 5 (dashed lines) show that the archaeologically observed velocities are easily accounted for by movement across complex landscapes. (Lower) Wave velocity expressed as a function of both the proportion of the landscape occupied P and the diffusion coefficient D (from Eq. 5).

The model we have proposed in this article to account for the velocity and trajectory of the colonization process emphasizes the interplay of population growth rates, hunter–gatherer adaptations, and the ecological and topographic complexity of landscapes. In particular, our model predicts that (i) the majority of Clovis-age sites should be associated with the types of ecological and topographic landscapes favorable to colonization, as outlined above (i.e., major river drainages and areas of high foraging return rates); (ii) the Clovis-age archaeological record should reflect the repeated use of regional landscapes because of the generational time-delays of the colonization process; (iii) regional variation in the size of home ranges should be influenced by both ecological productivity and, perhaps more importantly, the potential regeneration rates of high ranked prey (i.e., home range size should covary with high-ranked prey body size); and (iv) the earliest Clovis dates on the continent should occur on the far northern Plains, and the youngest Clovis dates for the initial occupation of a region should occur in Central America.

Methods

Wavefront/Bin Width.

We used wavefront bins of 450 km, although our results do not change quantitatively with reasonable adjustments in bin widths. A sensitivity analysis showed that our results are robust to bin widths of between ≈300 and 600 km wide (all P < 0.05). Below 300 km, bins are too narrow to capture variance in the sparse radiocarbon record, and above 600 km, there are not enough bins across the continent to make meaningful comparisons. We used widths of 450 km to provide enough bins across the continent for meaningful statistics but at the same time ensuring that sites in the analysis were far enough apart so we could be confident of seeing an underlying trend. A bin width of 450 km also helps us meet the first of two criteria laid out by Hazelwood and Steele (33) for archaeological diffusion modeling: (i) Because of modeling error, or errors in the width of the wavefront, the distance between two sites, Δx, must be greater than the width of the wavefront, () km. In our northern wave (the wave of interest) we note 〈Δx〉 > L, therefore meeting the first condition; and (ii) because of errors in radiocarbon dates, the difference in time between two sites, Δt, must be greater than the combined error rates of the two sites plus the modeling error, θ =|εA + εB| + 8/γ, where εx is the radiocarbon error at site x, and so Δt > θ. Again, working with averages, our average change in time between bins, Δt = 149, is significantly less than the modeling error, θ ≈ 335, meaning that we do not meet the second condition. Therefore, although we can be confident that our sample tracks the distance between traveling wavefronts over time, we must express caution in interpreting the dates here as the earliest dates within each wavefront bin. However, as the time it took for the colonization process to occur (11,200–10,600 = 600 radiocarbon years) is greater than the modeling error, we feel confident that our analysis accurately tracks the general trend in the early occupation history of the continent, if not the exact timing.

Radiocarbon Evidence.

In addition to the 17 radiocarbon assays reported as reliable by Waters and Stafford (6), we include six radiocarbon dates in our analyses that they do not evaluate (Table 1). In situations in which multiple dates were available, averages were calculated by using Calib 5.0.

Casper.

Recently dated camel bone from the Casper site in Wyoming suggests that a Clovis occupation underlies the Hell Gap kill at the site (45). A single Clovis projectile point was recovered from the site and several of the camel bones exhibited evidence of human breakage.

Big Eddy.

Big Eddy is a well stratified, multicomponent site in Missouri (46). A number of radiocarbon dates bracket the stratum containing the Clovis-aged assemblage, which yielded dated charcoal samples from the same lithological and cultural stratum 2 cm and 16 cm below a fluted projectile point.

Debert.

Haynes (23) evaluated Macdonald's (47) 13 radiocarbon dates and averaged them for the age estimate of the early Paleoindian occupation at Debert (48).

Hedden.

Two radiocarbon dates were taken from excavated charcoal samples (pine and spruce) associated with a buried, single component early Paleoindian occupation (49, 50).

Hiscock.

An early Paleoindian lithic assemblage, with fluted projectile points were recovered along with numerous bones of caribou and mastodon (51). Three culturally modified bones yielded the three radiocarbon ages that were averaged for use in this study.

Vail.

We use Barton et al.'s (27) average of dates from charcoal samples recovered at Vail. The charcoal samples were recovered by Gramly (52) from the habitation area of the Vail site within cultural features 1 and 2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Oskar Burger, Jim Boone, Ozzie Pearson, Bruce Huckell, Vance T. Holliday, Joaquim Fort, Arthur Speiss, Richard Laub, Douglas MacDonald, Barry Hewlett, and Ana Davidson. B.B. gratefully acknowledges support from National Science Foundation International Research Fellowship 0502293.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Haynes CV., Jr . In: Paleoamerican Origins: Beyond Clovis. Bonnichsen R, Lepper BT, Stanford D, Waters MR, editors. College Station, TX: Texas A&M Press; 2005. pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandryk CAS, Josenhans H, Fedje DW, Mathewes RW. Quaternary Sci Rev. 2001;20:301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dixon EJ. Bones, Boats, and Bison: Archaeology and the First Colonization of North America. Albuquerque, NM: Univ of New Mexico Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson DG, Gillam JC. Am Antiquity. 2000;65:43–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley B, Stanford D. World Archaeol. 2004;36:459–478. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters MR, Stafford TW., Jr Science. 2007;315:1122–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.1137166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosimann JE, Martin PS. Am Sci. 1975;63:304–313. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin PS. In: Pleistocene Extinctions: The Search for a Cause. Martin PS, Wright HE, editors. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ Press; 1967. pp. 75–120. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orr PC. Am Antiquity. 1962;27:417–419. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rick TC, Erlandson JM, Vellanoweth RL. Am Antiquity. 2001;66:595–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adovasio JM, Pedler D, Donahue J, Stuckenrath R. In: Ice Age People of North America: Environments, Origins, and Adaptations of the First Americans. Bonnichsen R, Turnmire KL, editors. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State Univ Press for the Center for the Study of the First Americans; 1999. pp. 416–431. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAvoy JM, McAvoy LD. Archaeological Investigations of Site 44SX202, Cactus Hill, Sussex County Virginia. Richmond, VA: Dept Hist Resour, Commonwealth of Virginia; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fort J, Mendez V. Phys Rev Lett. 1999;82:867–870. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fort J, Mendez V. Phys Rev E. 1999;60:5894–5901. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fort J. Antiquity. 2003:520–530. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fort J, Jana B, Humet J. Phys Rev E. 2004;70 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.031913. 031913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fort J, Pujol T, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Camb Archaeol J. 2004;14:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinhasi R, Fort J, Ammerman AJ. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:2220–2228. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fort J, Mendez V. Rep Prog Phys. 2002;65:895–954. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker RS, Gurven M, Hill K, Migliano A, Chagnon NA, De Souza R, Djurovic G, Hames R, Hurtado AM, Kaplan H, et al. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18:295–311. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDonald DH, Hewlett BS. Curr Anthropol. 1999;40:501–523. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewlett BS, van de Koppel JMH, Cavalli-Sforza LL. Man. 1982;17:418–430. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes CV, Jr, Donahue DJ, Jull AJT, Zabel TH. Archaeol East N Am. 1984;12:184–191. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimer PJ, Baillie MGL, Bard E, Bayliss A, Beck JW, Bertrand CJH, Blackwell PG, Buck CE, Burr GS, Cutler KB, et al. Radiocarbon. 2004;46:1029–1058. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ammerman AJ, Cavalli-Sforza LL. In: The Explanation of Culture Change. Renfrew C, editor. London: Duckworth; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchanan B, Collard M. J Anthropol Archaeol. 26:366–393. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barton CM, Schmich S, James SR. In: The Settlement of the American Continents. Barton CM, Clark GA, Yesner DA, Pearson GA, editors. Tucson, AZ: Univ of Arizona Press; 2004. pp. 138–161. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macaulay V, Hill C, Achilli A, Rengo C, Clarke D, Meehan W, Blackburn J, Semino O, Scozzari R, Cruciani F, et al. Science. 2005;308:1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1109792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fiedel SJ. J Archaeol Res. 2000;8:39–103. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiedel SJ. In: The Settlement of the American Continents: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Human Biogeography. Barton CM, Clark GA, Yesner DA, Pearson GA, editors. Salt Lake City: Univ of Utah Press; 2004. pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly RL, Todd LC. Am Antiquity. 1988;53:231–244. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haskell JP, Ritchie ME, Olff HI. Nature. 2002;418:527–530. doi: 10.1038/nature00840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hazelwood L, Steele J. J Archaeol Sci. 2004;31:669–679. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santos MC, Raposo EP, Viswanathan GM, Luz MGE. Europhys Lett. 2004;67:734–740. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raposo EP, Buldyrev SV, da Luz MGE, Santos MC, Stanley HE, Viswanathan GM. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:240601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.240601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Surovell T, Waguespack N, Brantingham PJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:6231–6236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501947102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steele J, Adams J, Sluckin T. World Archaeol. 1998;30:286–305. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meltzer DJ. J World Prehist. 1988;2:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campos D, Mendez V, Fort J. Phys Rev E. 2004;69 031115. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campos D, Fort J, Mendez V. Theor Popul Biol. 2006;69:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertuzzo E, Maritan A, Gatto M, Rodriguez-Iturbe I, Rinaldo A. Water Resour Res. 2007;43:W04419. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamilton MJ, Milne BT, Walker RS, Brown JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4765–4769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611197104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown CT, Liebovitch LS, Glendon R. Hum Ecol. 2007;35:129–138. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton MJ, Milne BT, Walker RS, Burger O, Brown JH. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 2007;274:2195–2202. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frison GC. Curr Res Pleistocene. 2000;17:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ray JH, Lopinot NH, Hajic ER, Mandel RD. Plains Anthropol. 1998;43:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacDonald GF. Debert: A Palaeo-Indian Site in Central Nova Scotia. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levine MA. Archaeol East N Am. 1990;18:33–63. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spiess A, Mosher J. Maine Archaeol Soc Bull. 1994;34:25–54. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spiess A, Mosher J, Callum K, Sidell NA. Maine Archaeol Soc Bull. 1995;35:13–52. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laub RS. In: The Hiscock Site: Late Pleistocene and Holocene Paleoecology and Archaeology of Western New York State. Laub RS, editor. Vol 37. Buffalo, NY: Bull Buffalo Soc Nat Sci; 2003. pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gramly MR. The Vail Site: A Paleo-Indian Encampment in Maine. Vol 30. Buffalo, NY: Bull Buffalo Soc Nat Sci; 1982. [Google Scholar]