Abstract

A critical challenge faced by sustainability science is to develop strategies to cope with highly uncertain social and ecological dynamics. This article explores the use of the robust control framework toward this end. After briefly outlining the robust control framework, we apply it to the traditional Gordon–Schaefer fishery model to explore fundamental performance–robustness and robustness–vulnerability trade-offs in natural resource management. We find that the classic optimal control policy can be very sensitive to parametric uncertainty. By exploring a large class of alternative strategies, we show that there are no panaceas: even mild robustness properties are difficult to achieve, and increasing robustness to some parameters (e.g., biological parameters) results in decreased robustness with respect to others (e.g., economic parameters). On the basis of this example, we extract some broader themes for better management of resources under uncertainty and for sustainability science in general. Specifically, we focus attention on the importance of a continual learning process and the use of robust control to inform this process.

Keywords: natural resources, resource management, vulnerability, policy design, environmental policy

As the 4-decade-old debate about resource scarcity and continued economic development (1, 2) continues (3–5), the challenges facing humanity are increasing in scale and complexity. Global climate change, depletion of fisheries worldwide (6, 7), and potential pandemics are vivid examples that highlight a key challenge facing sustainability science: decision making under pervasive uncertainty associated with complex social–ecological processes. Although statistical decision theory and dynamic optimization techniques provide guidance in this regard, they typically rely on the capacity to assign probabilities to uncertain events (8, 9). In cases like those mentioned above in which assignment of probabilities is often impractical or impossible, how can policy be developed?

One strategy might be to employ a panacea, a set of general principles that work well in a variety of circumstances. In this paper we use techniques from robust control to show that, although panaceas can be tuned to perform well for a range of “sufficiently similar” circumstances, their use can be very dangerous. The danger lies in perceiving different circumstances as sufficiently similar when, in fact, they differ in subtle but important ways. Specifically, we show that it is difficult, if not impossible, to devise a panacea for the set of all possible “similar” circumstances generated by the Gordon–Schaefer (10, 11) fishery model with a given range of parametric uncertainty. We find, rather, policies robust to uncertainty in one group of parameters are necessarily vulnerable to uncertainty in another group. Our analysis suggests, for example, that it is not possible to tune policies to achieve good performance over a given range of intrinsic growth rates (i.e., a set of different but sufficiently similar circumstances) without becoming more sensitive to variation in harvest costs.††

Addressing such subtle differences is a major challenge for resource management (7, 13, 14). Robust control provides several important lessons for avoiding the pitfalls of panaceas and improving resource management practice under pervasive uncertainty. Our analysis vividly illustrates why, as Ostrom (15) puts it, “effort[s] to impose a standard ‘optimal’ solution [are] ‘the’ problem rather than ‘the’ solution.” Using the classic bioeconomic model of a renewable resource, we show that panaceas can be even worse than inaction and that learning and continuous policy modification (16) are critical to resource management under pervasive uncertainty.

Panaceas, Uncertainty, and the Robust Control Framework

Ostrom (15) discusses the all-too-common use of panaceas in the governance of social–ecological systems (SESs). The tendency to employ panaceas may well be a reaction to the extremely difficult task of making decisions under conditions of pervasive uncertainty. Robust control, a methodology that seeks to develop control policies that maintain performance within a given set of uncertainty bounds, can be used to help avoid this tendency. Robust control can help analysts think in terms of robustness–vulnerability trade-offs to inform a management and learning process rather than finding the optimal solution given a particular characterization of uncertainty.

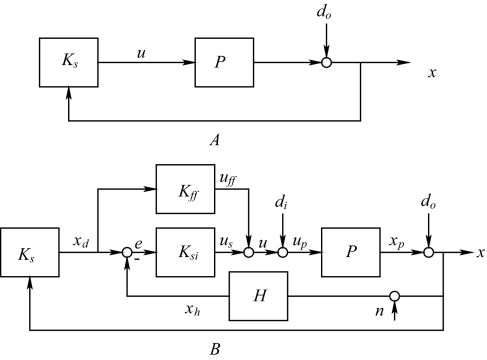

Fundamental to robust control is the idea that any system may be represented as a negative feedback loop involving subsystems that process signals, variables, or information (Fig. 1). Traditional optimal control in resource management contexts tends to focus on optimizing some performance measure in a loop like that in Fig. 1A. Arrows indicate internal signals (x and u) and an external signal (do) that represent the system output, control signal or policy, and exogenous shocks as a function of time, respectively. Blocks represent subsystems, with the symbols K and P referring to the controller and sets of (bio) physical processes, respectively. In traditional resource management problems, Ks in Fig. 1A is often assumed to be a benevolent social planner seeking to maximize social welfare, and P is typically a resource (fishery, forest, groundwater basin, etc.). On the basis of the output signal x (e.g., biomass), the social planner issues the command signal u (e.g., harvest effort) to the plant. If do = 0, the problem reduces to the standard optimal resource management problem (17). If do ≠ 0, it becomes a common resource management problem with additive uncertainty (circles represent addition).

Fig. 1.

Examples of feedback system block diagrams. (A) The single loop depiction frequently used in resource management problems. (B) A hierarchical control system with an “outer loop” that sets a goal and an “inner loop” that achieves the goal.

The stylized system shown in Fig. 1A is typically used to determine a general goal such as optimal escapement in a fishery, and the analysis typically neglects the problem of actually achieving the goal. We suggest that the hierarchical structure (18) in Fig. 1B with an “outer loop” that issues a reference command or goal xd that changes relatively slowly (e.g., optimal long-run escapement based on annual decisions of international governance bodies) to a relatively fast “inner loop” with controllers Ksi and Kff that actually implement this goal is a more useful way to view the system. Understanding this inner loop, because it actually achieves policy goals, should be central to policy design. In fact, failure to distinguish between systems A and B in Fig. 1 lies at the heart of frequent failures of optimal-control-based management panaceas (13, 14, 19). Several important, general resource management issues emerge from a focus on the inner loop.

Frequency Content of External Signals.

For engineered systems, signals xd, di, and do typically vary slowly, whereas n, noise associated with measurement of the output signal that is processed by the sensor H, typically varies rapidly. Measurements that are too infrequent can generate a low-frequency noise component (20) that prevents the control system from distinguishing between a low-frequency sensor output signal xh and a low-frequency reference command xd. Conducting the simple experiment of sampling the motion of a ceiling fan with low-frequency blinking eyes to generate the illusion of reversing the motion vividly illustrates the point. Likewise, infrequent measurements common in SESs may do much worse than simply missing important data.

The Natural Modes of Subsystems.

Each of the subsystems P, Ksi, Kff, and H in the inner loop may be described by ordinary differential equations or something more general. Thinking in terms of coupled subsystems highlights the importance of the natural, or uncontrolled, modes of each subsystem. In engineered systems, plants (21, 22) are typically designed with desirable natural modes [stable descent for an uncontrolled airplane, for example (18)], that makes controller design easier. In contrast, the natural modes of ecosystems, which include periodic, large-scale disturbances such as fire, often make them more difficult to control.

The subsystems Ksi (s means the controller is in series with the plant) and Kff (ff refers to a feed-forward controller that filters the reference command) are jointly referred to as the controller. Unlike engineered systems in which policies are typically implemented within a highly flexible embedded microprocessor, SESs implement policies through the potentially severely limited mechanism of human actors conditioned by institutions. Despite this significant distinction, the framework can nonetheless help assess the robustness characteristics of specific institutional arrangements and help determine how to modify them to meet particular objectives.

Treating the sensor, H, as a dynamic subsystem emphasizes that information gathering is subject to its own endogenous dynamics. In a fishery, H may involve a government agency assessing stocks, a dynamic process with inherent natural modes, including time delays and lags (23). The “tracking error,” defined as e = xd − x, measures how close the actual system is to its goal. In general, we want e = 0, but the measured error e = xd − xh does not represent a true error signal unless H = 1 (perfect measurements) and n = 0. This fact forces the analyst to confront uncertainty other than shocks to resource stocks or prices typical in the resource management problems. For example, even with perfect understanding of resource dynamics and no exogenous shocks, the analyst must still recognize that information gathering (sensing) and controller action are coupled dynamical systems that generate endogenous complexity and uncertainty that must be accounted for in policy design.

The Nature of Feedback.

Feedback implies that measurements from the biophysical system are used to generate u. Feedback can be used to (i) reduce sensitivity to uncertainty by enabling a system to adapt to changes in its state, (ii) alter undesirable dynamics, e.g., stabilize an unstable system, and/or (iii) reduce system management workload requirements (cruise control in your car). By way of illustration, consider a feedback system in which the blocks are simply positive constants (inputs are simply multiplied by a constant as they are processed by each block). With a little algebra, it is easy to show [see supporting information (SI) Appendix for details] that

and as Ksi becomes large,

This statement is strong: for good measurements (n ≈ 0), Eq. 2 says that x can be made to track xd as closely as we would like despite uncertainty about P, xd, di, and do simply by choosing Ksi sufficiently large. This simple idea also holds when P, Ksi, and H are dynamical systems and shows how powerful feedback can be. Unfortunately, in practice there are always unmodeled dynamics (equations left out of the description of P, dynamic uncertainty), which high gains can amplify with disastrous results. For example, the inappropriate use of feedback in resource management could destabilize (and destroy) an ecological system.

The Nature of Uncertainty.

Both exogenous signals and endogenous dynamics can be sources of uncertainty. Examples include limited understanding about the dynamics of subsystems (e.g., ecological dynamics are not fully understood), measurement errors (sensor dynamics and noise), and policy implementation errors (controller dynamics). We recognize that although they are all important for SESs, we cannot address all of these sources of uncertainty here. We focus on specific subsystems and restrict our attention to parametric uncertainty, which refers to the quality of knowledge about the values of parameters for a given model as opposed to dynamic uncertainty, which refers to the quality of the model itself. This choice limits the scope of our analysis but still allows us to explore the main issues of interest in this article.

Performance–Sensitivity Measures and Robustness.

The concept of sensitivity is natural to the study of robustness. Sensitivity SPv in the variable v with respect to P (22) can be defined as the ratio of the percent change in v and P. We want to reduce SPv for a given tolerance of performance deviation and level of uncertainty in P. When v = x, Kff = 0, and H = 1, it can be shown that SPx = 1/(1 + PKs) [this relationship also holds when P and K are described by linear ordinary differential equations with constant coefficients (22)]. This expression shows that increasing K can reduce sensitivity to uncertainty in P. Again, however, increasing K can amplify unmodeled dynamics with disastrous results.

Terms like stability, performance, and bandwidth may run counter to the sensibilities of social and ecological scientists. However, ecological and social systems do exhibit natural dynamics and, when linked through the action of agents based on information about the system, do constitute a closed feedback loop, as shown in Fig. 1. The robust control framework focuses on (i) achieving stability and performance robustness with respect to uncertainty in each of the subsystems (a prerequisite for sustainability) in closed feedback loops; (ii) achieving desirable command-following such as the capacity to meet social welfare objectives, low-frequency disturbance attenuation such as coping with climate shocks, and high-frequency noise attenuation; and (iii) achieving predictable or optimized performance. We turn now to the application of the robust control approach to the canonical fishery management problem.

Parametric Uncertainty and Critical Depensation in the Gordon–Schaefer Fishery

Here we illustrate fundamental trade-offs between performance, robustness, and vulnerability as well as the challenges (impossibility) in achieving globally robust policies (panaceas). We explore two cases for the ecological dynamics: purely compensatory and critically depensatory growth (see SI Appendix for mathematical details). Note that we will explore the robustness properties of the model, assuming that the structure is correct but that parameters cannot be measured with certainty. Analysis of the case when the model structure is not fully understood (i.e., dynamic uncertainty), although clearly important for SESs, is beyond the scope of this article. Several important insights emerge from the analysis of parametric uncertainty alone.

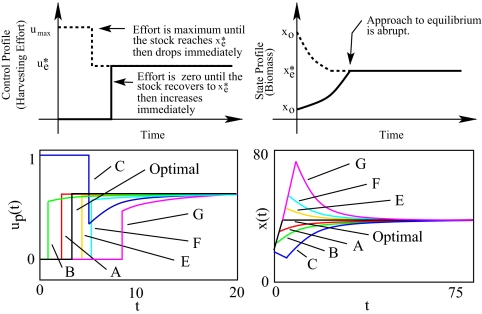

In terms of Fig. 1A, the classical optimal control law (with do = 0) can be viewed as the controller (e.g., benevolent social planner), K, issuing the bang–bang control shown in Fig. 2(see SI Appendix for details) to the logistic ecology, P. We focus on exploring the trade-offs always associated with attempting to achieve the goal prescribed by the optimal policy despite do, di, and uncertainty in K, P, and H. To do so, we developed a sensitivity measure SθoJo and a family of <4,500 alternative control laws based on the inner loop in Fig. 1B [see SI Appendix for an overview and Rodriguez et al. (12) for details] and compared their performance to that of the optimal control. The structure of the alternative control policies is based on that of the optimal control: they are variations of the optimal that can, for a given initial condition, drive the population to xd = x*e and hold it there (Fig. 2 Upper).

Fig. 2.

Control and state trajectories for the renewable resource problem. (Upper) General optimal control and state trajectories for initial biomass xo lower and higher than the long-run optimal x*e (solid and dashed lines, respectively). (Lower) Examples of alternative control laws examined. The alternative control laws differ in that they switch earlier (A and B) or later (C–G) than the optimal and approach the long-run equilibrium smoothly rather than abruptly (compare C in lower right with the solid black curve in the upper right graphs).

Examples of control paths and resulting state paths for our family of controls are shown in Fig. 2 Lower. The black line is the optimal bang–bang control. Different values of three parameters, gff ∈ (−500, 500), gs ∈ (−500, −100), and zs ∈ (0.1, 0.75), generate the colored alternative management strategies. For example, a manager may choose to be more aggressive and begin harvesting earlier but approach equilibrium more smoothly than the optimal (A and B controllers) or be more precautionary and begin later and allow the stock to recover beyond x*e before approaching x*e (E and F controllers).

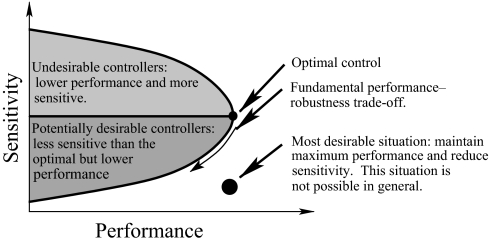

Using a set of tools developed in Matlab (12), the robustness properties of these alternative strategies were exhaustively explored. Each controller's sensitivity SθoJo and performance J were characterized and plotted. Fig. 3 shows an example of what such a so-called Pareto plot looks like in theory. The optimal has, by definition, the best performance in all cases but not necessarily the best sensitivity characteristics. The most desirable controllers would lie directly below the optimal with reduced sensitivity and no loss in performance. Unfortunately, in general, such controllers do not exist.

Fig. 3.

Explanation of Pareto plots.

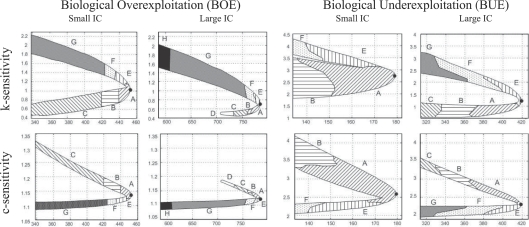

Pareto plots are shown in Fig. 4 for four representative bioeconomic cases: low and high harvesting costs, which lead to biological overexploitation (BOE) (typical situation in world fisheries) and biological underexploitation (BUE), respectively, each with low and high initial conditions. What is striking is that controllers exhibit fundamental trade-offs between robustness and vulnerability as seen by tracking the movement of clusters of families of controllers in Fig. 2 Lower. For example, A controllers reduce sensitivity to uncertainty in k in the BOE case but increase sensitivity to uncertainty in c, especially in the BUE case. Combining the information in these plots with analytical results (12) allows us to define fundamental robustness–vulnerability trade-offs. Specifically, policies that are robust to uncertainty in the stock and rate-of-return parameters r, k, xo, and δ necessarily increase vulnerability to uncertainty in the harvest and revenue parameters p, c, and q. The converse is also true: control laws that improve the performance–sensitivity properties for harvest and revenue parameters necessarily result in worse performance–sensitivity properties for the stock and rate-of-return parameters (region E within the subplots). In terms of actual fisheries management, choosing policies from region A to become robust to fluctuations in stock dynamics (r and k), for example, necessarily increases the vulnerability of the fishery to fluctuations in the effectiveness of harvest activities (q). This fundamental trade-off illustrates that there are no panaceas: unless a manager gets lucky and all uncertain parameters fall within one of these two groups, it is impossible to become globally robust (find a panacea), even in the simplest logistic ecology.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity–performance trade-offs for four bioeconomic cases. IC, initial condition. See Fig. 3 for the interpretation of the graphs.

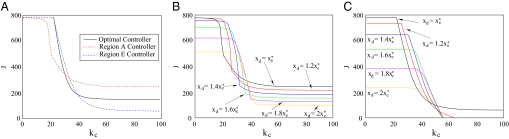

Next we explore the implications of critically depensatory growth. We explore the performance of region A and region E controllers when F(x) is replaced by Fc(x) [see SI Appendix for details concerning Fc(x)]. We consider the biological overexploitation, high initial-condition case. Here, policy action begins when the biomass is 50% greater than the long-run optimal, which lies below maximum sustainable yield (MSY). We use the parameter set k = 100 kilotons, r = 0.3, discount rate δ = 0.1, cost of effort c = 13.24 (chosen so that x*e = 0.75·xMSY = 37.5), fish price P = 10 million dollars per kiloton, catchability q = 0.3 per fleet power year, and maximum harvest umax = 1. In this case, x*e = 37.5. Fig. 5A shows the performance of the optimal control and examples of region A and region E controllers applied for different values of kc. When kc = 0, the optimal control generates a discounted net present value of just under 800 million dollars. Note that if kc is small (for example <10 or 10% of carrying capacity), all three controllers perform well, and there is no drop-off in social welfare when kc is uncertain. In fact, if kc is bounded above by 10, then it is not uncertain in any meaningful way.

Fig. 5.

Social welfare vs. kc for different controllers. (A) J vs. kc for the optimal and two examples of region A and region E controllers. (B and C) J vs. kc for region A and region E controllers with xd = (1 + α)x*e for α = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0, respectively.

As kc increases beyond 10, the performance of the controllers begins to differ markedly. Note that the optimal controller seeks to drive the state x to 37.5. If x < 37.5, x > 37.5, or x = 37.5, harvesting effort is 0, 1, or 0.625 (62.5% of the maximum fleet power), respectively. The approach to equilibrium is thus “harsh” and can fall into cycles as the state cycles above and below 37.5 with efforts switching from 0 to 1. Both region A and region E controllers have “softer landings” (Fig. 2 Lower). Region A controllers are more aggressive, switching on earlier or off later if the initial state is below or above 37.5, respectively (which is the case in Fig. 5A). Region E controllers are the opposite.

With these controller characteristics in mind, we can interpret the curves in Fig. 5A. The kink in the optimal and region E curves near kc ≈ 22 corresponds to when the kink in the curve Fc(x) (see SI Appendix) falls below the equilibrium harvest line, 0.625qx. With kc ≤ 22, this line will intersect Fc(x) and form a stable equilibrium point. When kc > 22, this intersection vanishes, precluding a stable equilibrium, which then “confuses” the controllers as they seek the desired equilibrium. As long as kc < 37.5, however, the controllers can adjust if they do not push the stock below kc. The optimal cycles on and off as it attempts to find 37.5. Each time the controller overshoots, it has to wait for the stock to recover, which amounts to lost revenue. The larger kc, the more rapidly the growth rate decreases for stock levels below the kink. This decrease leads to slower recovery, higher lost revenues, and hence deteriorating performance for 22 < kc < 37.5. There is little difference between region E and optimal controllers for kc in this range. The region A controller's performance, however, begins to drop off earlier because it is more aggressive and tends to push x(t) into the interval between kc and 37.5 in which critical depensation causes the stock to recover slowly. Because the region E controller is less aggressive and shuts off for higher values of x(t), it avoids this region, and its performance drops off less rapidly than for the optimal and region A controllers.

What is going on as kc continues to increase and the welfare begins to level out at a very low value? In this case, kc is sufficiently large that all of the control laws drive the population to extinction. It is interesting that the region A controller does best in this region because it harvests more, earlier. If the population is going extinct anyway, it is best to harvest as much a possible rather than letting it die of its own accord. The less aggressive region E controllers turn off earlier, stand by, and allow the population to go extinct of its own accord rather than harvest it. This comparison illustrates problems with transporting policies. Suppose the policy maker chooses region A controllers to deal with critical depensation on the basis of the intuition that they reduce sensitivity to biological parameters such as k and r given the biological nature of critical depensation. If kc is small, the policy will do worse than optimal. Suppose, however, the policy maker chooses to use region E controllers because they are less aggressive and may thus avoid critical thresholds. Region E controllers make very little difference for low kc and needlessly stand by and watch a doomed resource evaporate if kc is large.

Ideally, a robust controller for kc should extend the point at which performance begins to drop off rapidly as far right as possible without too much reduction in performance. Neither region A nor region B controllers are successful in this regard because they focus on the nature of approach paths to equilibrium rather than the core problem of critical depensation: the existence and nature of the equilibrium itself. To illustrate, we modified the control laws by changing xd from x*e to xd = (1 + α)x*e for α > 0 to stop fishing when the biomass is greater than the long-run optimal. Obviously, such controllers can extend the safe zone, but at what performance cost? Fig. 5 B and C shows the performance of region A and region E controllers as α is increased. Notice that very conservative policies almost double the size of the safety zone but at significant cost. The more aggressive region A controller requires a larger α to increase its robustness. Such policies may be more appealing politically because they allow for heavy exploitation in the near-term (and do not immediately affect livelihoods) but require lower exploitation levels in the long-term (typically beyond the planning horizon of both harvesters and politicians). Region E controllers are the oppositie and may thus be much less politically appealing. This tradeoff can be seen by comparing the region A controller with xd = 2x*e with the region E controller with xd = 1.4x*e, both of which achieve roughly the same level of robustness (zero sensitivity to kc for kc between 0 and ≈30). However, the region E controller achieves this level of robustness without giving up as much performance. A comparison of these controllers with the optimal with xd = (1 + α)x*e (data not pictured) further suggests that the early switching-off characteristic of region E controllers does not add to robustness and simply reduces welfare. The optimal controller can achieve the same robustness characteristics with xd = 1.4x*e with higher returns. This result suggests that effective policies must address specific vulnerabilities (nature of equilibria vs. approach paths) rather than families of vulnerabilities (biological vs. economic parameters). Although the necessity of adding the equilibrium considerations to our control laws to enhance robustness may seem obvious in hindsight, it is symptomatic of a much more general phenomenon: of all of the N variables, processes, or issues that the policy maker has considered, it is the omitted (n + 1)th variable, process, or issue that is critical.

Lessons from Robust Control

Our analysis has demonstrated how robustness and vulnerability can be partitioned among different groups of parameters. We can choose controllers that increase robustness to uncertainty about the stock and rate-of-return parameters r, k, xo, and δ or the harvest and revenue parameters p, c, and q, but not both. Furthermore, there is a price for increasing robustness to a particular class of disturbances to be paid in increased sensitivity to other parameter uncertainty.

The story is not as pessimistic as it may seem. These results simply highlight the importance of continual learning. The robust control framework makes it clear that there are fundamental limitations to what can be achieved for any given level of understanding of the system dynamics. Thus, there is no policy that, once perfected, will work from that point on. Policies will not only be limited in their effectiveness by uncertainty, but will also always generate significant new vulnerabilities. Policies should thus always be viewed as experiments and should be embedded in a continual learning and adaptive management process (24).

Robust control can help structure this process by exposing how policies distribute robustness and vulnerability across a given system. If possible, policies can be chosen to maximize robustness to those parameters about which least is known at the expense of being sensitive to parameters about which most is known. Associated with such a policy would be a learning process to first reduce ambiguity concerning parameters to which the policy is most sensitive. Learning might then be focused on reducing ambiguity of parameters to which the policy is more robust in order to enhance performance. In the case that actual parameter uncertainty does not match any potential policy well, for example when both c and r are uncertain in the fishery example, decision makers cannot match policies to their actual information situation. However, they can choose which type of sensitivity they are more willing to live with and, again, focus a learning process on that set of ambiguities most important to reducing this sensitivity.

More broadly, the application of robust control highlights general issues and challenges faced by all feedback systems. Key among these is the nested nature of systems as shown in Fig. 1B. Each layer in the system processes different types of information at different spatial and temporal scales and addresses different types of problems. Given the emphasis of institutional analysis on nested enterprises (25, 26), robust control is a natural tool in this area. The nested nature of information and actions highlights the need for a systematic methodology to combine large-scale, abstract, thematic knowledge and tacit, small-scale, fine-grained, experiential knowledge to effectively address resource management problems.

What else does robust control contribute to our understanding of panaceas and resource management under pervasive uncertainty? It helps us understand what panaceas are, why they are so common, why they can't be found in general, and when they are most dangerous. Panaceas are classes of control polices that are portable and require only moderate tuning. Because developing a control system from scratch is an expensive process, the temptation to transport existing policies and tune them for new situations is great. If the process of transporting and tuning could be systematized, something resembling a panacea might result. In general, however, this process is very challenging: even for “similar” airplanes, let alone SESs, this “portability feature” has been difficult to achieve even after 30 years of research on the issue. Nonetheless, if uncertainty is limited to modest measurement problems or disturbances and the structure of the problem is known and well defined, panaceas may not, in principle, be problematic. Panaceas become dangerous if the underlying dynamic structure of the system is unknown, and it is no longer possible (in principle) to apply a given control structure (panacea) and tune parameters to achieve a fit. These problems are all related to the simple fact that policy design is fundamentally limited by the quality of available models and uncertainty bounds. These limitations suggest that better policies require investment in improving models and reducing uncertainty bounds. Unfortunately, the investment required to detect the effects of policies in SESs may be too costly for society to bear, which may, in turn, lead to the persistence of panaceas.

This discussion suggests that an important component of decision-making strategies in the face of pervasive uncertainty is the recognition of these limits. Performance always comes at a cost in robustness. The Federal Aviation Administration requires commercial airplane designs to be inherently stable so they glide down nicely in case of an engine failure (18). Performance can be increased by trading off some of the robustness generated by this “natural” stability property. Airplane designs that are naturally unstable offer considerable fuel savings but have obvious implications for robustness. Similarly, robustness always incurs vulnerability costs; complex financial instruments can help manage individual risk but may amplify collective risks, leading to macroeconomic volatility and instability (27). Tainter (28) has observed in various complex societies that as SESs increase in complexity, more control effort is required to maintain performance. For SESs, more tailored institutional crafting is necessary to cope with increasingly connected and complex social organization that may amplify perturbations and reduce stability. At some point, the cost of additional control effort may outweigh the benefits of enhanced performance (28). In hunter–gatherer societies, the energy output/input ratio of food consumption can easily be >20, whereas in highly industrialized societies, this ratio is often <1 (29). This advancement indicates the high dependence of modern agricultural systems on artificial energy inputs and the inherent vulnerability of food supply systems to energy scarcity.

Concluding Remarks

In this article we have discussed the application of the robust control framework to SESs. This exercise has exposed fundamental trade-offs that indicate that the best we can hope for is the development of management structures and policies that are somewhat portable between closely related SESs. We thus suggest that the resource management community focus on the development of tools that will permit managers to systematically analyze, understand, and properly address fundamental trade-offs. This analysis can be used to inform a conversation about the fact that to achieve high performance for a particular system, society needs to choose to which uncertainties it wishes to be robust, to which uncertainties it may choose to be vulnerable, and how to focus its learning resources. This is an extremely important conversation for both policy makers and citizens alike to begin to have.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Ostrom, W. Brock, C. Perrings, and K. Smith for providing useful comments on earlier drafts of this article. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant BCS-0527744.

Abbreviation

- SES

social–ecological system.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

All of the results in this article are based on the control theoretic ideas laid out in Rodriguez et al. (12).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0702655104/DC1.

References

- 1.Simon JL. Science. 1980;208:1431–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.7384784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon JL. The Ultimate Resource. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maugeri L. Science. 2004;304:1114–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1096427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant L. Science. 2005;309:52–54. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5731.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon RB, Bertram M, Graedel TE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1209–1214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509498103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myers RA, Worm B. Nature. 2003;423:280–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark CW. Popul Ecol. 2006;48:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raiffa H. Applied Statistical Decision Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertsekas DP. Dynamic Programming and Stochastic Control. New York: Academic; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon H. J Polit Econ. 1954;62:124–142. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaefer MB. J Fish Res Board Can. 1957;14:669–681. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez AA, Cifdaloz O, Anderies JM, Janssen MA, Dickeson J. Robustness-Vulnerability Trade-Offs in Renewable Resource Management. Tempe: Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity, Arizona State University; 2006. Tech Rep 01-06. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark CW, Munro GR, Sumaila UR. J Environ Econ Manag. 2005;50:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland D, Gudmundsson E, Gates J. Mar Policy. 1999;23:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostrom E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15181–15187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702288104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brock WA, Carpenter SR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15206–15211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702096104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark CW. Mathematical Bioeconomics: The Optimal Management of Renewable Resources. 2nd Ed. New York: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson RC. Flight Stability and Automatic Control. 2nd Ed. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark CW. The Worldwide Crisis in Fisheries: Economic Models and Human Behavior. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oppenheim AV, Willsky AS, Nawab SH. Signals and Systems. 2nd Ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice–Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogata K. Modern Control Engineering. 4th Ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice–Hall; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez AA. Analysis and Design of Feedback Control Systems. Tempe, AZ: Control3D; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson J, Yan L, Wilson C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15212–15217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702241104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walters C. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources. New York: Macmillan; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrom E. Governing the Commons. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrom E. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chichilnisky G, Wu HM. J Math Econ. 2006;42:499–524. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tainter JA. The Collapse of Complex Societies. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pimentel D, Pimentel M. Food, Energy and Society. Niwot, CO: Colorado Univ Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.