Abstract

What is already known about this subject

Several studies have shown that inappropriate medications induce adverse health outcomes in the elderly.

The hypothesis of Beers et al. that these inappropriate medications increase the likelihood of adverse drug reactions is debated and checked in patients admitted to hospital.

What this study adds

Inappropriate medications do not seem to be the major cause of adverse drug reactions in the elderly.

More than the inappropriateness of the drugs themselves, it is the inappropriate use of drugs that is to be tackled when treating the elderly.

The main preventable factor is the reduction in the number of drugs given.

Aim

To study the occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) linked to inappropriate medication (IM) use in elderly people admitted to an acute medical geriatric unit.

Methods

All the elderly people aged ≥ 70 years admitted to the acute medical geriatric unit of Limoges University hospital (France) over a 49-month period were included, whatever their medical condition. For all the patients, clinical pharmacologists listed the medications given before admission and identified the possible ADRs. The appropriateness of these medications and the causal relationship between drugs (either appropriate or not) and ADRs were evaluated.

Results

Two thousand and eighteen patients were included. The number of drugs taken was 7.3 ± 3.0 in the patients with ADRs and 6.0 ± 3.0 in those without ADRs (P < 0.0001). Sixty-six percent of the patients were given at least one IM prior to admission. ADR prevalence was 20.4% among the 1331 patients using IMs and 16.4% among those using only appropriate drugs (P < 0.03). In only 79 of the 1331 IM users (5.9%) were ADRs directly attributable to IMs. The IMs most often involved in patients with ADRs were: anticholinergic antidepressants, cerebral vasodilators, long-acting benzodiazepines and concomitant use of two or more psychotropic drugs from the same therapeutic class. Using multivariate analysis, after adjusting for confounding factors, IM use was not associated with a significant increased risk of ADRs (odds ratio 1.0, 95% confidence interval 0.8, 1.3).

Conclusion

Besides a reduction in the number of drugs given to the elderly, a good prescription should involve a reduction in the proportion of IMs and should take into consideration the frailty of these patients.

Keywords: adverse drug reaction, elderly, inappropriate medication

Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in older people are a major public health issue. The elderly are more likely to experience ADRs because of age-related changes in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drugs they are given to treat their multiple pathological conditions. ADRs are up to seven times more frequent in 70–79-year-olds than in those aged 20–29 years [1]. In Europe, 20% of ambulatory elderly people suffer from ADRs; nearly 10–20% of acute geriatric hospital admissions are believed to be drug related [2, 3].

Lindley et al. have investigated the relationship between inappropriate medications (IMs) and the occurrence of ADRs and shown that nearly 50% of ADRs were due to drugs that had absolute contraindications and/or were unnecessary [4]. Beers proposed explicit criteria to identify IM use in elderly patients, first in nursing homes and then wherever they lived [5, 6]. These criteria were based on a drug list compiled from reviews of the literature and submitted to a consensus of experts using a modified Delphi technique. Potential IMs were drugs with an unfavourable risk/benefit ratio when safer or equally effective alternatives were available. Thus, it was hypothesized that taking these drugs was a major factor influencing the likelihood of ADR occurrence among the elderly.

Several authors have studied the influence of IM use, as defined by Beers, on health outcomes in the elderly. There seems to exist a positive relationship between IM use on one hand and healthcare costs on the other [7, 8] or use of healthcare services (hospitalizations, in- or outpatient visits, emergency department admissions) [8–11]. Nevertheless the direct influence of IM use on mortality is difficult to assess from the conflicting results published, especially as all adverse health outcomes are not necessarily ADRs [7, 9–14]. Only a few investigators have studied the association between IM use as defined by Beers and the occurrence of ADRs [13, 15]. Onder failed to show any association between IM use and ADRs in hospitalized older adults [13], whereas Chang found a positive association in elderly outpatients on their first visit [15]. However, in these studies neither the involved IMs nor the seriousness of ADRs were detailed.

The aim of the present study was to assess the prevalence of ADRs and describe those ADRs directly linked to IMs among elderly patients admitted to an acute medical geriatric unit.

Methods

Study population

A systematic and prospective drug surveillance study was carried out in the acute geriatric unit of Limoges University Hospital, France. From January 1994 to April 1996 and from May 1997 to January 1999, all patients aged ≥ 70 years were included, whatever their medical condition. Subjects admitted repeatedly were excluded if less than 1 month had elapsed between admissions. Patients were admitted from their own homes, from nursing homes, other care units or other hospitals.

The following data was collected: age, gender, weight, origin of the patient (own home or institution: hospital, nursing home), medical history, serum concentration of common analytes, number of drugs and length of hospital stay. Subjects were classified into three age categories: 70–79 years, 80–89 years and ≥ 90 years. In order to take into account the complexity of the patient's health status, a simplified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index was used [11, 16]. This index covers nine diagnoses with a maximum sum of 11 (weight in parentheses): myocardial infarction (1), congestive heart failure (1), cerebrovascular disease (1), dementia (1), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1), connective tissue disease (1), diabetes (1), impaired renal function (2) and any tumour (2). Creatinine clearance was computed using the Cockcroft–Gault formula [17]. Patients with creatinine clearance <30 ml min−1 were classified as having impaired renal function.

Potential IM use

On admission of the patients, pharmacologists established the list of all drugs received from written prescriptions; when possible, patients and their families were asked about the treatment given and eventually the in-charge general practitioners or carers most familiar with the patients were questioned. The list of drugs thus established at admission was considered to reflect as precisely as possible the treatment received before hospitalization.

Potential IMs were identified using the 1997 Beers criteria adapted to French practice. This list has been used in several studies in France [16, 18] to estimate the prevalence of potential IM use. Most of the Beers criteria were included in the French list, except meperidine (not available in France), drugs necessitating dose information (digoxin, iron supplements, some benzodiazepines such as lorazepam, oxazepam, alprazolam, triazolam, temazepam and a benzodiazepine analogue, zolpidem) and drugs that should not be used in the elderly with specific medical conditions. Three criteria were added: concomitant use of two (or more) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), concomitant use of two (or more) psychotropic drugs from the same therapeutic class and use of any medications with anticholinergic properties other than those listed by Beers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Potentially inappropriate medications used on admission from the acute medical geriatric unit of Limoges University Hospital, and involved in ADRs and serious ADRs

| All patients (N = 2018) n (%) | Patients with ADRs (N = 385) n (%) | Patients with serious ADRs (N = 220) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any inappropriate medication | 1331 (66.0) | 79 (20.5) | 56 (25.5) |

| Antiemetic drugs with extrapyramidal properties | 35 (1.7) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Cerebral vasodilators* | 734 (36.4) | 24 (6.2) | 19 (8.6) |

| Analgesics | |||

| Propoxyphene or dextropropoxyphene | 159 (7.9) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.9) |

| Pentazocine | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Sedative or hypnotic drugs | |||

| Long-acting benzodiazepines (half-life ≥ 20 h)† | 468 (23.2) | 23 (5.9) | 18 (8.2) |

| Chlordiazepoxide or diazepam | 24 (1.2) | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.5) |

| Meprobamate | 73 (3.6) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Barbiturates | 43 (2.1) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Drugs with anticholinergic properties | |||

| Anticholinergic antidepressants | 150 (7.4) | 26 (6.7) | 16 (7.3) |

| Anticholinergic muscle relaxants and antispasmodic drugs | 31 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Anticholinergic H1 antihistamines | 70 (3.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diphenhydramine | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal antispasmodic drugs | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Disopyramide | 16 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

| Indomethacin | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Phenylbutazone | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Antihypertensive | |||

| Methyldopa | 15 (0.7) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (1.4) |

| Reserpine | 1 (0.05) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | |||

| Dipyridamole | 81 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ticlopidine | 25 (1.2) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Hypoglycaemic | |||

| Chlorpropamide | 7 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Added criteria adapted to French practice | |||

| Concomitant use of two or more psychotropic drugs from the same therapeutic class | 133 (6.6) | 9 (2.3) | 7 (3.2) |

| Concomitant use of two or more nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 56 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other anticholinergic drugs not mentioned by Beers | 91 (4.5) | 5 (1.3) | 5 (2.3) |

Pentoxifylline, nicergoline, dihydroergotamine, Ginkgo biloba, piracetam, …

Bromazepam, prazepam, clorazepate, nordazepam, …

Determination of ADRs

According to the World Health Organization, an ADR is defined as any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended and which occurs at doses normally used in human beings for diagnosis, prophylaxis or therapy of disease, and excluding a failure to accomplish the intended purpose [19]. The presence of ADRs was identified from the clinical manifestations observed on admission, from the laboratory tests and hospital reports. Two physicians from the Pharmacovigilance Centre (L.M., Y.N.) jointly judged the probability that any drug taken prior to admittance had caused or contributed to signs or symptoms suggesting an ADR according to the French causality scale [20]. Only ‘definite’ and ‘probable’ ADRs were taken into account.

An ADR was considered to be serious when signs and symptoms were directly responsible for hospitalization and/or were life threatening or fatal. ADRs were classified according to type of mechanism: type A reactions are dose-dependent ADRs related to the pharmacological effects of the medication and type B reactions are neither dose dependent nor related to the known drug pharmacological properties and do not improve when the dose is reduced (reactions often immunologically mediated or having a genetic basis) [21].

Signs and symptoms were classified into nine groups of disorders: cardiovascular, ionic or renal, neuropsychological, digestive, digitalis toxicity, metabolic, haematological, cutaneous and others. Only ADRs present at the time of admission – whether or not they were the reason for admission – were considered to be relevant.

Statistical analysis

Data was analysed using STATA 8 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Statistical analyses were performed with χ2 tests for dichotomous variables and t-test for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to estimate the effect of the number of drugs taken, of sex, patient origin and comorbidity index on ADR outcome. In a subsequent analysis, logistic regression was used to estimate the effect of IM use on ADR outcome; variables considered for adjustment were those associated with ADR outcome at P ≤ 0.25 in bivariate analysis. A P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the 49-month observation period, 2018 patients aged ≥ 70 years were admitted. Characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean (±SD) age of the patients was 85.2 ± 6.6 years. Only 59 (3%) of the 2018 subjects studied were not taking any drugs at the time of hospital admission.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Patients with ADRs (N = 385) % (n) | Patients without ADRs (N = 1633) % (n) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.3 | ||

| 70–79 years | 17.4 (67) | 20.4 (333) | |

| 80–89 years | 54.8 (211) | 51.4 (840) | |

| ≥90 years | 27.8 (107) | 28.2 (460) | |

| Female | 72.2 (278) | 68.7 (1122) | 0.2 |

| Origin | 0.004 | ||

| Home-dwelling | 67.6 (227) | 75.3 (1096) | |

| Institution | 32.4 (109) | 24.7 (360) | |

| Use of inappropriate drugs | 70.6 (272) | 64.8 (1059) | 0.03 |

| Number of drugs (mean ± SD) | 7.3 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 3.0 | <0.0001 |

| Days of hospitalization (mean ± SD) | 13.7 ± 7.3 | 13.4 ± 8.7 | 0.5 |

| Comorbidity Index | 0.7 | ||

| 0 | 5.4 (21) | 6.6 (108) | |

| 1–2 | 28.6 (110) | 28.9 (472) | |

| 3–4 | 43.4 (167) | 44.3 (723) | |

| >6 | 22.6 (87) | 20.2 (330) | |

| Impaired renal function | 73.8 (284) | 68.8 (1124) | 0.06 |

| Dementia | 16.6 (64) | 19.7 (321) | 0.15 |

| Myocardial infarction | 19.5 (75) | 21.2 (347) | 0.5 |

| Congestive heart failure | 30.4 (117) | 25.4 (415) | 0.05 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 16.6 (64) | 16.6 (271) | 0.99 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20.6 (79) | 22.7 (371) | 0.35 |

| Connective tissue disease | 30.6 (118) | 30.9 (506) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes | 11.2 (43) | 10.7 (175) | 0.8 |

| Tumour | 15.3 (59) | 15.8 (258) | 0.8 |

The proportion of patients receiving at least one potential IM on admission was 66.0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 63.8, 68.0]. Cerebral vasodilators (36.4%) were the drugs most frequently used, then long-acting benzodiazepines (23.2%), dextropropoxyphene (7.9%), anticholinergic antidepressants (7.4%) and concomitant use of two or more psychotropic drugs of the same therapeutic class (6.6%) (Table 2).

ADRs

Four hundred and sixty ADRs were considered ‘definite’ or ‘probable’ and involved 385 patients (19% of the study population). In 201 patients, ADRs were the cause of hospital admission. The three main ADR symptoms were cardiovascular (31.5%), ionic or renal (24.3%) and neuropsychological (13.7%) (Table 3). Of ADRs, 78.4% were classified as type A reactions and 3.2% type B. ADRs were serious in 57.1% of patients suffering from an adverse effect (220/385); 36 patients died: 14 from digitalis toxicity, eight from dehydration (aggravated by diuretics), five from hyperkalaemia (spironolactone, amiloride), one from acute renal failure (lisinopril), four from haemorrhage with an anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug (heparin, acenocoumarol, fluindione, ticlopidine), three from cytopenia (cytarabine, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) and one from severe hypoglycaemia (glipizide). The outcome was favourable in 96.9% of the moderate ADRs. After adjustment for potential confounders, the number of drugs taken was associated with a significantly increased risk of ADR (four to six drugs vs. three or less, OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.1, 5.5; seven to nine drugs vs. three or less, OR 4.6, 95% CI 2.8, 7.4; ≥ 10 drugs vs. three or less, OR 5.9, 95% CI 3.6, 9.9).

Table 3.

Signs and symptoms of adverse drug reactions

| Signs and symptoms | n = 460 (%) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular (postural arterial hypotension, heart rhythm or conduction disorders) | 145 (31.5) |

| Ionic or renal effect (dehydration, ionic disorders, renal failure) | 112 (24.3) |

| Neuropsychological (vigilance impairment, agitation, confusion, extrapyramidal syndrome, sleep disorder) | 63 (13.7) |

| Digestive (diarrhoea, vomiting, constipation, hepatic or pancreas disorders*) | 40 (8.7) |

| Digitalis toxicity | 33 (7.2) |

| Metabolic (dysglycaemia, dysthyroidism, gynecomastia, SIADH, adrenal failure, phosphorus-calcium disorder) | 30 (6.5) |

| Haematological (cytopenia, coagulation disorder, haemorrhage) | 25 (5.4) |

| Cutaneous (rash, pruritus, urticaria) | 4 (0.9) |

| Other | 8 (1.8) |

Eight hepatitis and two pancreatitis. SIADH, Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone.

The 460 ADRs detected were caused by 810 drugs, either singularly or in combination (Table 4). Cardiovascular drugs were the most commonly involved drugs in ADRs (47.5%).

Table 4.

Drug classes and drugs involved in ADRs

| Drug class (n,%) | Drugs (n = 810) | Nonproprietary name (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular drugs (385, 47.5%) | Diuretics (108) | Furosemide (33) |

| Hypokalaemia-inducing diuretics (12) | ||

| Spironolactone (16) | ||

| Diuretic associations (47) | ||

| Antiarrhythmic drugs (76) | Digoxin (62) | |

| Amiodarone (13) | ||

| Flecainide (1) | ||

| Calcium antagonists (48) | Diltiazem (12) | |

| Nicardipine (17) | ||

| Nifedipine (5) | ||

| Amlodipine (4) | ||

| Others (10) | ||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (46) | Captopril (17) | |

| Enalapril (13) | ||

| Ramipril (4) | ||

| Others (12) | ||

| Anti-ischaemia drugs (42) | Piribedil (8) | |

| Buflomedil (6) | ||

| Naftidrofuryl (6) | ||

| Nicergoline (5) | ||

| Trimetazidine (5) | ||

| Others (12) | ||

| Nitrates (32) | ||

| β-Blockers (18) | Atenolol (5) | |

| Acebutolol (5) | ||

| Propranolol (4) | ||

| Others (4) | ||

| Other drugs (15) | ||

| Psychotropic drugs (195, 24.1%) | Antidepressants (79) | Paroxetine (16) |

| Fluoxetine (13) | ||

| Other SSRIs (3) | ||

| Clomipramine (10) | ||

| Amitriptyline (6) | ||

| Other tricyclics (9) | ||

| Mianserine (11) | ||

| Tianeptine (7) | ||

| Others (4) | ||

| Antipsychotics (61) | Haloperidol (14) | |

| Tiapride (12) | ||

| Thioridazine (8) | ||

| Levomepromazine (6) | ||

| Sulpiride (5) | ||

| Others (16) | ||

| Psychotropic drugs (195, 24.1%) | Anxiolytics, hypnotics (55) | Alprazolam (9) |

| Bromazepam (8) | ||

| Lorazepam (6) | ||

| Zoplicone (5) | ||

| Clorazepate, acepromazine, aceprometazine (5) | ||

| Zolpidem (4) | ||

| Others (18) | ||

| Neurology drugs (51, 6.3%) | Anti-Parkinson drugs (45) | Levodopa-benserazide (27) |

| Trihexyphenidyle (7) | ||

| Bromocriptine (4) | ||

| Selegiline (3) | ||

| Others (4) | ||

| Antiepileptics (6) | Carbamazepine (4) | |

| Phenobarbital (2) | ||

| Anti-inflammatory drugs (17, 2.1%) | NSAIDs (9) | Ketoprofene (2) |

| Ibuprofene (1) | ||

| Diclofenac (1) | ||

| Piroxicam (1) | ||

| Others (4) | ||

| SAIDs (8) | Prednisolone (6) | |

| Hydrocortisone (2) | ||

| Analgesics (15, 1.8%) | Opioids (11) | Morphine (5) |

| Dextropropoxyphene (3) | ||

| Buprenorphine (1) | ||

| Tramadol (1) | ||

| Codeine (1) | ||

| Non-opioids (4) | Paracetamol (4) | |

| Anti-cancer drugs (11, 1.4%) | Alkylating agents (5) | |

| Anti-androgens (3) | ||

| LH-RH agonists (2) | ||

| Antimetabolites (1) | ||

| Other drugs (136, 16.8%) |

SSRI, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SAID, steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

IMs and ADRs

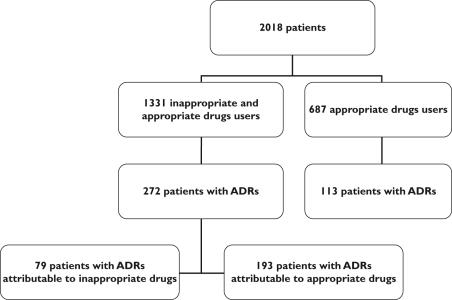

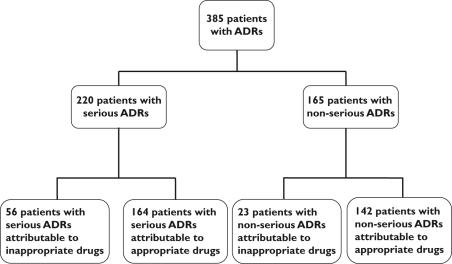

ADR prevalence was 20.4% among the 1331 patients using IMs and 16.4% among those using only appropriate drugs (P< 0.03) (Figure 1). However, after adjusting for potential confounders, the use of IMs was not associated with a significantly increased risk of ADR (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.8, 1.3). In fact, in only 79 of the 1331 IM users (5.9%) were ADRs directly attributable to IMs (Figure 1). The most often involved IMs in the 385 patients with ADRs were: anticholinergic antidepressants, cerebral vasodilators, long-acting benzodiazepines and concomitant use of two or more psychotropic drugs from the same therapeutic class (Table 2). ADRs attributable to IMs mainly involved cardiovascular (40.2%), neuropsychological (22.6%), ionic or renal (19.6%) and gastrointestinal (12.4%) systems. Serious ADRs were attributable to IMs in 25.5% of cases (56/220) (Figure 2). Among the 79 patients with an ADR linked to an IM, this ADR was serious in 70.9% of cases (56/79) (Figure 2). Digoxin toxicity was encountered in 33 patients and was responsible for 21 serious ADRs. The serum digoxin concentration (2.2 ± 0.7 ng ml−1) was above the usual therapeutic value (1.0–2.0 ng ml−1) in most patients. When comparing the populations treated or not with digoxin, women treated were older (87.7 ± 5.6/85.6 ± 6.5 years), lighter (52 ± 13/55 ± 13 kg) and had a more depressed renal function (creatinine clearance 29.2 ± 11.9/33.1 ± 13.4 ml min−1), respectively (P< 0.001). No such difference was detected in men.

Figure 1.

Relation between adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and appropriateness of the drugs given

Figure 2.

Relation between seriousness of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and appropriateness of the drugs given

Independent of IM use, 62 patients of the 2018 included developed an ADR linked to digoxin and 20 an ADR linked to the above-listed benzodiazepines or to zolpidem. When these two drug categories were added to the IM list, 1555 (1331 + 224) patients were receiving at least one IM on admission. The prevalence of ADRs in this population was then 10.4% (79 + 62 + 20/1555).

Discussion

In this study involving an elderly population admitted to hospital, ADR prevalence was fairly high and ADRs were encountered more often in those patients using at least one IM than in those not taking these drugs (20.4% vs. 16.4%, P < 0.03). However, multivariate analysis showed no relation between IM use and the risk of experiencing an ADR. After establishing the causal relationship between ADRs and drugs, it appears that only 5.9% of the patients taking at least one IM experienced an ADR attributable to IMs. When adding digoxin and the listed benzodiazepines to the existing Beers list, the increase in the prevalence of ADRs, from 5.9% to 10.4%, remains limited. Consequently, we can consider that IMs overall account for only a small proportion of ADRs.

Based on our results, drugs with anticholinergic effects and long-acting benzodiazepines (half-life ≥ 20 h) were particularly unsafe. These IMs have already been considered by Beers as high-risk drugs [6].

The simultaneous administration of two (or more) psychotropic drugs from the same therapeutic class, an additional criterion added by French experts, was frequently involved in ADRs. This study confirms the choice of this criterion as inappropriate prescribing in the elderly. In contrast, no ADR was linked to the concomitant use of two (or more) NSAIDs. Nevertheless, we think this association should still be considered as ‘inappropriate’ because the concomitant administration of NSAIDs is frequent [16] and NSAIDs are known to induce more serious gastrointestinal, renal and cardiovascular effects in the elderly [22, 23].

Cerebral vasodilator administration was associated with one-third of the ADRs. These drugs, whose efficacy is questionable, account for 25 different chemical entities in France. They are among the IMs most often prescribed to the French elderly [16, 18]. According to the definition by Beers, cerebral vasodilators should still be regarded as inappropriate in the elderly.

The use of dextropropoxyphene in the elderly is debated. This drug is considered by Beers to be inappropriate (although with low risk) by extrapolation of data derived from younger patients. Goldstein conducted a literature review to evaluate the efficacy and safety of dextropropoxyphene compared with other opioids in older patients and found that it appeared to provide pain relief equivalent to that obtained from comparator agents, and to have a safety profile equivalent or superior to that of these drugs [24]. In the present study, dextropropoxyphene was involved in ADRs in only three cases (2%) out of the 159 dextropropoxyphene users, confirming this viewpoint. We therefore believe this medication should not be considered as inappropriate in the elderly. Alternatives, such as codeine, could hardly be regarded as safer.

Digoxin was not included in the French list of IMs, as information on the dose was seldom available in the studies performed [16, 18]. In our study, digoxin was involved in several ADRs, two-thirds of which were serious, whatever the administered dose. However these ADRs seemed to be related to an overdose.

Reduction of renal function is probably the main factor explaining the relationship between therapeutic dose and high steady-state serum concentrations of digoxin [25]. A reduced maintenance dose of digoxin is recommended when renal function is diminished with ageing. Physicians often tend to administer too high a digoxin dose in patients with reduced renal function, as shown in the Digoxin Intervention Group Trial (DIG trial) [26]. This situation is often found in the elderly, who are consequently overtreated and develop signs of toxicity when they are given a dose > 0.125 mg day−1. The serum digoxin concentration should be maintained between 0.5 and 2 ng ml−1 and probably closer to the lower limit [27]. This has been confirmed in a study showing a significant relationship between digoxin serum concentration and toxicity in patients with heart failure; concentrations from 0.5 to 0.9 ng ml−1 bring a beneficial effect, whereas concentrations > 1.2 ng ml−1 seem harmful [28].

Actually, as digoxin should no longer be the drug of choice in congestive heart failure, it is less and less often administered and is substituted by other drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, loop diuretics, spironolactone and β-blockers [29]. Taking all these points into account, we think digoxin, whatever the dose given, should be considered as an IM if periodical monitoring of serum concentration is not undertaken.

Similarly, other studies have reported that drugs involved in most of the ADRs in the elderly were: cardiovascular drugs such as digoxin and diuretics, psychotropic agents, anti-Parkinson and anti-inflammatory drugs [2, 3, 30]. Some other drugs such as amiodarone, nifedipine and fluoxetine were often involved in ADRs; these drugs have been recently added to the last updated list of IMs [31]. However, the majority of the IMs from this last list were not involved in ADRs in our study.

The causality assessment method we used could be criticised, as well as other assessment methods. However, a consensus was obtained between two senior clinical pharmacologists used to imputability evaluation for many years, which is a more accurate appreciation than an evaluation from only one expert, as is the case in some other studies.

Most ADRs belonged to the A type, i.e. were preventable. So, the use of an IM list oversimplifies the multifactorial situation of elderly patients. Besides IM use, other preventable prescribing factors in the elderly are: dosage, duration, duplication and indication of the treatment, drug–drug interactions or drug–disease interactions [30, 32, 33]. These factors were not specifically evaluated in the present study. However, using multivariate analysis without adjustment in IM use, we identified a positive association between the number of drugs given and ADR occurrence. Studies of IMs have identified a positive association between the number of drugs given and IM use [8, 9, 18, 34–37]. Chang et al. identified a statistical interaction between these two variables [15]. This interaction may indicate that the presence of either IM prescribing or the prescription of five or more drugs will favour ADR development, but the presence of both will not further increase the risk of ADRs. In addition, a positive association was found by Chang et al. between inappropriate prescription and ADR occurrence [15]. After adjustment, like Onder et al.[13], we did not identify this last relation. In fact, this link is probably weaker than that between the number of drugs and the occurrence of ADRs. So, two main facilitating factors of ADR development could be considered: the number of drugs on the one hand and the number of IMs on the other. However, the strength of the links is not equivalent. In our opinion, the high number of drugs is the main ADR facilitating factor, whereas the inappropriateness of drugs is a subordinate factor. So the first action to be taken in order to reduce the incidence of ADRs in the elderly is to reduce the number of drugs prescribed, so as to favour essential medications.

Other strategies can be proposed addressing both patients and treatments: minor comorbid conditions should be left out of consideration, whereas frailty, renal insufficiency and alteration in cognitive function should be taken into account. Treatments should be periodically reconsidered and adapted to the renal function [38]. Poor compliance should be hypothesized and self administration of over-the-counter drugs is to be discouraged. Occurrence of some symptoms should be identified as the adverse consequence of drug administration, the first treatment of which is drug withdrawal and not the addition of a new medication [39].

Conclusion

IM use does not seem to be the major cause of ADRs in the elderly. Other closely linked preventable factors are involved in ADR development, such as frailty and renal insufficiency, which are to be taken into account when patients in general are considered.

In order to reduce the prevalence of ADRs, IM use should be discouraged, but the first step to be taken is the reduction in the number of drugs administered. As a consequence, the number of IMs will be reduced. This is the most beneficial way to enhance the quality of the treatments given. Polymedication reduction in the elderly should be a constant preoccupation of physicians for a direct beneficial effect, allowing a decrease of the prevalence of drug–drug interactions and for easing the burden on healthcare costs.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: None declared.

This study was sponsored and funded by the French Drugs Agency (AFSSaPS) (Programme de recherche clinique). AFSSaPS had no specific role in the design or conduct of the study, or in the interpretation of the data collected.

References

- 1.Beard K. Adverse reactions as a cause of hospital admission in the aged. Drugs Aging. 1992;2:356–67. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199202040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Routledge PA, O'Mahony MS, Woodhouse KW. Adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:121–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01875.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkin PA, Veitch PC, Veitch EM, Ogle SJ. The epidemiology of serious adverse drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1999;2:141–52. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199914020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindley CM, Tully MP, Paramsothy V, Tallis RC. Inappropriate medication is a major cause of adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1992;21:294–300. doi: 10.1093/ageing/21.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beers MH, Ouslander JG, Rollingher I, Reuben DB, Brooks J, Beck JC. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use in nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1825–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S, Rappaport HM, Bennett LT. Inappropriate drug prescribing and related outcomes for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries residing in nursing homes. Clin Ther. 1996;18:183–96. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(96)80189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fick DM, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Heuvel RV, Tadlock JG, Gottlieb M, Cangialose CB. Potentially inappropriate medication use in a Medicare managed care population: association with higher costs and utilization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2001;7:407–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin MH, Wang LC, Jin L, Mulliken R, Walter J, Hayley DC, Karrison TG, Nerney MP, Miller A, Friedmann PD. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1232–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perri M, Menon AM, Deshpande AD, Shinde SB, Jiang R, Cooper JW, Cook CL, Griffin SC, Lorys RA. Adverse outcomes associated with inappropriate drug use in nursing homes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:405–11. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klarin I, Wimo A, Fastbom J. The association of inappropriate drug use with hospitalization and mortality. A population-based study of the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:69–82. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Kuchibhatla M, Artz MB, Boult C, Gross CR, Garrad J, Schmader KE. Impact of inappropriate drug use on mortality and functional status in representative community dwelling elders. Med Care. 2002;40:166–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onder G, Landi F, Liperoti R, Fialova D, Gambassi G, Bernabei R. Impact of inappropriate drug use among hospitalized older adults. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:453–9. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0928-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raivio MM, Laurila JV, Strandberg TE, Tilvis RS, Pitkala KH. Use of inappropriate medications and their prognostic significance among in-hospital and nursing home patients with and without dementia in Finland. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:333–43. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang CM, Liu PY, Yang YH, Yang YC, Wu CF, Lu FH. Use of the Beers criteria to predict adverse drug reactions among first-visit elderly outpatients. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:831–8. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Nouaille Y, Fourrier A, Merle L. Impact of hospitalization in an acute medical geriatric unit on potentially inappropriate medication use. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:49–59. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechevallier-Michel N, Gautier-Bertrand M, Alperovitch A, Berr C, Belmin J, Legrain S, Saint-Jean O, Tavernier B, Dartigues JF, Fourrier-Reglat A The 3C Study Group. Frequency and risk factors of potentially inappropriate medication use in a community-dwelling elderly population: results from 3C study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005. pp. 813–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.WHO. WHO Technical Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1972. p. 498. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begaud B, Evreux JC, Jouglard J, Lagier G. Imputation of the unexpected or toxic effects of drugs. Actualization of the method used in France. Thérapie. 1985;40:111–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawlins MD, Thomas SHL. Mechanisms of adverse drug reactions. In: Davies DM, editor. Davies's Textbook of Adverse Drug Reactions. 5. London: Chapman & Hall; 1998. pp. 40–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh G. Recent considerations in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastropathy. Am J Med. 1998;105:31S–38S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray MD, Brater DC. Adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on renal function. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:559–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-8-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstein DJ, Turk DC. Dextropropoxyphene: safety and efficacy in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:419–32. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guggenheim R, Reidenberg MM. Serum digoxin concentration and age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1980;28:553–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1980.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shlipak MG, Smith GL, Rathore SS, Massie BM, Krumholz HM. Renal function, digoxin therapy, and heart failure outcomes: evidence from the Digoxin Intervention Group Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2195–203. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000135121.81744.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miura T, Kojima R, Sugiura Y, Mizutani M, Takatsu F, Suzuki Y. Effect of aging on the incidence of digoxin toxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:427–32. doi: 10.1345/aph.19103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams KF, Patterson JH, Gattis WA, O'Connor CM, Lee CR, Schwartz TA, Gheorghiade M. Relationship of serum digoxin concentration to mortality and morbidity in women in the digitalis Investigation Group Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aronow WS. Treatment of systolic and diastolic heart failure in the elderly. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doucet J, Jego A, Noel D, Geoffroy CE, Capet C, Coquard A, Couffin E, Fauchais AL, Chassagne P, Mouton-Schleifer D, Bercoff E. Preventable and non-preventable risk factors for adverse drug events related to hospital admission in the elderly. A prospective study. Clin Drug Invest. 2002;22:385–92. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2716–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Avorn J, McCornick J, Jain S, Eckler M, Benser M, Edmondson AC, Bates DW. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events in nursing homes. Am J Med. 2000;109:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas EJ, Brennan TA. Incidence and types of preventable adverse events in elderly patients: population based review of medical records. BMJ. 2000;320:741–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanlon JT, Fillenbaum GG, Schmader KE, Kuchibhatla M, Horner RD. Inappropriate drug use among community-dwelling elderly. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:575–82. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.6.575.35163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aparasu RR, Fliginger SE. Inappropriate medication prescribing for the elderly by office-based physicians. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:823–9. doi: 10.1177/106002809703100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spore DL, Mor V, Larrat P, Hawes C, Hiris J. Inappropriate drug prescriptions for elderly residents of board and care facilities. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:404–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caterino JM, Emond JA, Camargo CA. Inappropriate medication administration to the acutely ill elderly: a nation wide emergency department study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1847–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Marcheix A, Bouthier A, Merle L. Problems encountered with the evaluation of renal function in the elderly in order to adjust drug administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1041–6. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.7.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merle L, Laroche ML, Dantoine T, Charmes JP. Predicting and preventing adverse drug reactions in the very old. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:375–92. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]