Abstract

What is already known about this subject

Plasma concentrations of clozapine (CLZ) and its active metabolite vary considerably at a given dosage.

A number of patient-related factors have been reported to increase the variability of plasma CLZ concentrations, with gender, age and smoking behaviour representing some of the more important contributing variables

However, results of previous studies concerning these factors have been inconsistent and most studies were conducted in western populations.

What this study adds

Using this ethnically unique, relatively large sample, we replicated some findings in western populations, including large interindividual variability of plasma CLZ concentrations, significant effects of gender on plasma CLZ concentrations.

Female patients had significantly higher levels than males and no significant differences in plasma CLZ concentrations were observed between male smokers and nonsmokers, despite the CLZ dosage for smokers being significantly higher.

Aim

To study the relationship between age, gender, cigarette smoking and plasma concentrations of clozapine (CLZ) and its metabolite, norclozapine (NCLZ) in Chinese patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Data from a therapeutic drug monitoring programme were analysed retrospectively. One hundred and ninety-three Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia were assessed using clinical data forms. Steady-state plasma concentrations of CLZ and NCLZ were assayed using high-performance liquid chromatography. Comparisons of dosage and plasma CLZ concentrations were undertaken between males (n = 116) and females (n = 77), younger (≤40 years, n = 82) and older patients (>40 years, n = 111) and current male smokers (n = 50) and nonsmokers (n = 66).

Results

(i) Plasma CLZ concentrations demonstrated large interindividual variability, up to eightfold at a given dose; (ii) there were significant effects of gender on plasma CLZ concentrations (relative to dose per kg of body weight) with female patients having significantly higher concentrations than males (30.09 ± 24.86 vs. 19.87 ± 3.55 ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1; P < 0.001); (iii) there were no significant differences in plasma CLZ concentrations between those patients ≤40 years old and those >40 years; and (iv) there were no significant differences in plasma CLZ concentrations between male smokers and nonsmokers, despite the CLZ dosage for smokers being significantly higher.

Conclusions

Plasma CLZ concentrations vary up to eightfold in Chinese patients. Among the patient-related factors investigated, only gender was significant in affecting CLZ concentrations in Chinese patients with schizophrenia, with female patients having higher levels.

Keywords: Chinese race, clozapine, gender, patient-related variables, plasma levels, schizophrenia

The atypical antipsychotic clozapine (CLZ) has been commonly used in China for the treatment of schizophrenia since the early 1980s, largely because of its efficacy and low cost [1]. As in the West, it is mainly used for those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, although use in acute schizophrenia is not uncommon [2]. Therapeutic drug monitoring of CLZ has been widely applied in clinical practice for more than 10 years in China, with most Chinese pharmacologists considering such monitoring to be of clinical value [3].

Many studies internationally have suggested that plasma concentrations of CLZ and its active metabolite, norclozapine (NCLZ) vary considerably at a given dosage [4–8]. A number of patient-related factors have been reported to increase the variability of plasma concentrations of CLZ, with gender, age and smoking behaviour representing some of the more important contributing variables [4, 5, 9–18]. However, results of previous studies concerning the effects of gender, age and smoking behaviour have been inconsistent. Some early studies demonstrated that women have higher concentrations of CLZ and NCLZ [4, 5, 12, 19, 20], but other studies have not been able to replicate this [6, 21, 22]. Fabrazzo et al.[23] have suggested that the gender differences increase after 4–6 weeks, but disappear after 24 weeks of treatment. Some studies have also reported age-related differences, with older age being associated with higher plasma concentrations [4, 5, 12]. Again, not all studies have confirmed this [6, 21]. Cigarette smoking is another factor of interest, with findings inconsistent between studies. Some groups have reported that cigarette smoking may reduce CLZ or CLZ plus NCLZ concentrations and thereby clinical response to CLZ [4, 5, 11, 16]. This has been confirmed in one Chinese study on a small sample [24]. Others, however, have not found such differences [6].

A small number of studies have been carried out in Chinese populations, two based in Taiwan and another two in mainland China using small samples [24, 25]. Chang et al.[8] reported on determinants of steady-state plasma concentrations of CLZ and its metabolites desmethylclozapine (norclozapine) and clozapine-N-oxide in 162 Taiwanese patients with refractory schizophrenia. The mean plasma CLZ concentration was 566.9 ± 398.8 ng ml−1, with dose-dependent plasma CLZ concentrations being found. The interpatient variation was up to 12-fold in patients receiving the same dose (400 mg day−1). Another study was undertaken by the same group [12], with the daily doses of CLZ ranging from 100 to 900 mg, at a mean ± SD dose of 379.5 ± 142.2 mg. Lane et al.[12] found that after accounting for the effects of gender, age and body weight by multiple linear regression, each 1-mg increment in the daily dose raised the CLZ concentration by 0.31%, NCLZ by 0.27% and clozapine-N-oxide by 0.16%. Female patients had 34.9% higher CLZ and 36.3% higher NCLZ concentrations. No gender differences were demonstrated for clozapine-N-oxide concentrations. Each 1-year increment in age was found to elevate CLZ concentrations by 1.1%, NCLZ by 1.0% and clozapine-N-oxide by 1.0%. Body weight was not related to concentrations of either CLZ or its two metabolites.

We conducted the present study in a large sample to investigate the influence of gender, age and smoking behaviour on CLZ plasma parameters in Chinese patients with schizophrenia. We also aimed to evaluate the variability of CLZ and NCLZ plasma concentrations in this population, as well as the NCLZ/CLZ ratio and the sum of NCLZ plus CLZ concentrations (total analytes). As described by Palego et al.[16], we accounted for both the ratios and sums of CLZ and its metabolites, as these parameters are important indices of CLZ metabolism. In particular, the sum of CLZ plus NCLZ concentrations divided by dose/weight is related to CLZ clearance [26]. Previous reports have used only dosage or concentration rather than dosage and concentrations per kg body weight [5, 8, 12, 24, 25]. Furthermore, the samples used in most previous reports have been too small for meaningful subgroup comparisons.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

One hundred and ninety-three subjects from Beijing Anding Hospital (affiliated with the Capital University of Medical Sciences) were enrolled in the current study. All patients participated voluntarily after written informed consent had been obtained. The study was approved by a human subjects committee of the Beijing Anding Hospital. The study period was from August 1999 to January 2002. All subjects were inpatients who met the DSM-IV [27] diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. One hundred and sixteen of the subjects were male and 77 female. The ages of subjects ranged from 17 to 74 years. The mean ± SEM age was 43.6 ± 0.8 years, the mean prior CLZ treatment course was 202.5 ± 122.3 weeks and the mean ± SEM body weight was 70.4 ± 0.84 kg (range 45–109 kg). Those with severe hepatic or renal disease were excluded from the study. Patients were receiving a clinically established oral dose of CLZ for acute or maintenance treatment. Steady-state plasma concentrations of CLZ and NCLZ were measured in patients after >10 days from initiation of treatment (mean ± SEM treatment duration 419.5 ± 65.7 days). Steady-state concentrations were ensured by maintaining subjects at the CLZ dosage for at least 7 days (CLZ has a half-life of 12–26 h [28]).

Drug administration

All patients were on CLZ monotherapy. Those patients on CLZ who were also receiving typical antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers or anticonvulsant agents were excluded, but those receiving benzodiazepines and anticholinergic agents as adjunctive treatments were included. Patients concurrently receiving Chinese herbal medicines were not included. The individual daily doses ranged between 75 and 600 mg day−1 (mean ± SEM 297.0 ± 9.2 mg day−1). Daily doses per kg body weight ranged from 0.71 to 11.05 mg kg−1 (mean ± SEM 4.35 ± 0.15 mg kg−1). Patient liver function tests were routinely assessed prior to sampling and were within the normal range for all subjects enrolled.

Assessments

Blood samples (10 ml) were collected from patients in heparin-coated tubes in the early morning (between 06.30 and 08.00 h), at an average of 11 ± 1.5 h after the last intake of CLZ. Samples were then centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min, plasma collected and stored at −20°C until assay, which was performed within 1 week.

Analyte plasma concentrations were evaluated by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with ultraviolet detection at 254 nm, modified from Weigmann and Hiemke [29], with desipramine as the internal standard. An intersil ODS-3 column was used as the solid phase. The mobile phase was composed of methanol, acetonitrile and n-butyl-amine-acetic acid buffer (5 : 35 : 60). The lowest detection limits assayed were 3–10 ng and the level of detection was 6–16 µg l−1 in plasma. The extraction recoveries were 65–81%. The inter- and intra-assay variance was <10%. Intraday and interday coefficients of variations were <5%. The standard curves were linear within the range of 25–800 µg/l. This assay was not interfered with by routine psychotropic drugs or other drugs. All reagents used were of HPLC grade. Linear calibration curves for CLZ and NCLZ within the range of 25–1000 ng ml−1 were attained [30].

Data management and statistical analysis

All data was managed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 11.0 and all statistical analyses were performed with this program. The nonparametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test was used for comparing CLZ plasma concentration parameters between the various groups under study. CLZ plasma parameters were compared as normalized concentration (i.e. the plasma level at a given dose per kg body weight, ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1 body weight). The Spearman rank correlation test was applied to correlate patient daily doses of CLZ and body weight with CLZ and NCLZ plasma concentrations (both their sum and ratio). The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Distribution of plasma clozapine concentration in 193 schizophrenia patients

The daily doses per kg body weight administered to patients ranged between 0.71 and 10.68 mg kg−1 (mean ± SEM 4.19 ± 0.18 mg kg−1) for men and between 1.10 and 11.05 mg kg−1 (mean ± SEM 4.59 ± 0.25 mg kg−1) for women. Moreover, women in this sample were older than men (46.3 ± 11.6 years vs. 41.7 ± 10.9 years; P = 0.006) and the prevalence of cigarette smoking was higher (43.1%; 50/116) in men than in women (1.3%; 1/78).

The average total sample plasma concentrations in the 193 patients were: CLZ, median (percentiles) 340.7 (53.6–1770.6) ng ml−1 (mean ± SEM 426.5 ± 20.4 ng ml−1); normalized CLZ concentration, median (percentiles) 17.33 (3.9–174.8) ng ml−1; NCLZ, median (percentiles) 163.2 (33.9–848.4) ng ml−1; normalized NCLZ concentration, median (percentiles) 8.64 (1.5–57.5) ng ml−1; sum, median (percentiles) 503.7 (116.3–2446.3) ng ml−1; and normalized sum concentration, median (percentiles) 25.54 (5.9–232.2) ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1. The ratio of NCLZ/CLZ was: median (percentiles) 0.45 (0.20–2.1).

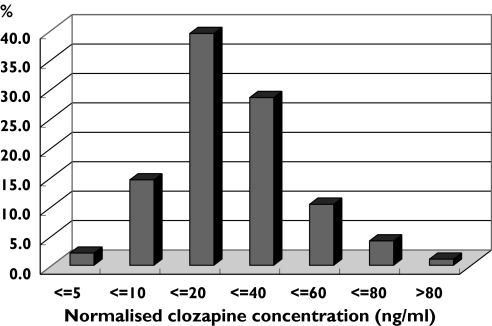

Figure 1 details the frequency of plasma CLZ concentrations in all 193 patients. The concentrations of more than half the cases were <20 ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1 and >95% of cases were <60 ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of normalized plasma clozapine concentration in 193 Chinese schizophrenic inpatients treated with clozapine

Concentration variation of fixed dosage clozapine (400 g day−1) following treatment for more than 7 days

To investigate variations in steady-state concentrations at a fixed dose of CLZ, 18 patients were selected who had received 400 mg day−1 for >7 days and their steady-state plasma concentrations were analysed (Table 1). We found that even at such a given dosage, plasma concentrations (ng ml−1) varied up to 8.7-fold.

Table 1.

Steady-state concentrations of clozapine at 400 mg day−1 (n = 18)*

| Item | Range | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLZ (ng ml−1) | 202.2–1770.6 | 544.3 | 389.0 |

| Normalized CLZ concentration† | 7.22–57.86 | 19.74 | 12.82 |

| Normalized NCLZ concentration† | 3.48–23.63 | 9.18 | 5.65 |

| Normalized sum concentration† | 12.07–79.94 | 29.27 | 18.34 |

| NCLZ/CLZ ratio | 0.26–0.76 | 0.487 | 0.133 |

400 mg day−1for at least 7 days.

ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1body weight. CLZ, Clozapine; NCLZ, norclozapine.

Comparison of clozapine parameters by gender, age and smoking behaviour

Dosage, plasma CLZ concentrations and concentrations/dose/kg body weight are shown in Table 2. Comparisons by gender, age and smoking status were made and are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Dosage, plasma clozapine concentrations and comparison by gender, age and smoking status*

| Item | All samples (n = 193) | Male (n = 116) | Female (n = 77) | P | ≤40 years old (n = 82) | >40 years old (n = 111) | P | Male smokers (n = 50) | Male non-smokers (n = 66) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43.6 ± 11.4 | 41.7 ± 10.9 | 46.3 ± 11.6 | 0.006 | 33.3 ± 5.8 | 51.1 ± 8.1 | <0.0001 | 40.5 ± 8.5 | 42.7 ± 12.5 | 0.268 |

| Body weight (kg) | 70.4 ± 11.6 | 72.5 ± 11.5 | 67.2 ± 11.1 | 0.001 | 70.2 ± 12.4 | 70.5 ± 11.0 | 0.859 | 71.8 ± 10.8 | 73.1 ± 12.5 | 0.572 |

| Dosage (mg day−1) | 296.9 ± 127.6 | 296.6 ± 128.1 | 296.3 ± 127.5 | 0.820 | 328.3 ± 123.5 | 273.7 ± 126.2 | 0.003 | 339.00 ± 134.9 | 264.4 ± 113.4 | 0.002 |

| Dosage (mg day−1 kg−1) | 4.35 ± 2.07 | 4.22 ± 1.97 | 4.58 ± 2.21 | 0.238 | 4.88 ± 1.97 | 3.62 ± 1.79 | 0.001 | 4.84 ± 2.13 | 3.74 ± 1.73 | 0.002 |

| Clozapine (ng ml−1) | 426.5 ± 283.0 | 386.0 ± 281.4 | 487.7 ± 276.1 | 0.001 | 471.4 ± 321.3 | 393.4 ± 247.4 | 0.143 | 432.1 ± 354.6 | 351.0 ± 206.1 | 0.442 |

| Norclozapine (ng ml−1) | 189.4 ± 119.5 | 176.1 ± 127.9 | 209.1 ± 103.5 | 0.002 | 211.7 ± 135.2 | 173.3 ± 104.4 | 0.032 | 207.9 ± 161.5 | 152.0 ± 89.2 | 0.073 |

| Sum (ng ml−1) | 617.6 ± 387.7 | 564.1 ± 393.2 | 696.7 ± 367.7 | 0.001 | 688.2 ± 442.8 | 566.7 ± 355.5 | 0.070 | 646.3 ± 504.3 | 502.2 ± 270.6 | 0.229 |

| Normalized CLZ concentration† | 23.96 ± 19.63 | 19.87 ± 3.55 | 30.09 ± 24.86 | <0.001 | 22.01 ± 14.67 | 25.34 ± 22.60 | 0.257 | 18.06 ± 13.08 | 21.25 ± 13.85 | 0.194 |

| Normalized NCLZ concentration† | 10.08 ± 6.55 | 8.52 ± 4.30 | 12.43 ± 8.33 | <0.001 | 9.67 ± 5.23 | 10.38 ± 7.38 | 0.462 | 8.29 ± 4.41 | 8.61 ± 4.22 | 0.704 |

| Normalized sum concentration† | 34.2 ± 25.6 | 28.55 ± 16.95 | 42.52 ± 32.71 | <0.001 | 32.06 ± 19.25 | 35.74 ± 29.35 | 0.330 | 26.57 ± 16.86 | 29.90 ± 17.01 | 0.304 |

| NCLZ/CLZ ratio | 0.49 ± 0.22 | 0.51 ± 0.26 | 0.46 ± 0.14 | 0.262 | 0.49 ± 0.19 | 0.49 ± 0.24 | 0.986 | 0.54 ± 0.26 | 0.48 ± 0.26 | 0.229 |

All comparisons were performed using t-tests or Mann–Whitney U-tests (mean ± SE).

ng ml−1 mg−1 day−1 kg−1body weight. CLZ, Clozapine; NCLZ, norclozapine.

First, CLZ dosage and plasma concentration parameters were compared between male and female patients. While there were no differences in dosage between males and females, significant differences were found in both plasma parameters and plasma parameters/dose/kg body weight concentrations between the genders. Female patients had about one-third higher concentrations than those of male patients. There was no gender difference in the ratio of NCLZ/CLZ concentrations.

Fabrazzo et al.[23] reported that gender differences in CLZ concentrations were significant after 4–6 weeks, but disappeared after 24 weeks of treatment. Based on their findings, patients were selected who had been onCLZ for between 6 and 24 weeks and those who had been on CLZ for >24 weeks, and the plasma CLZ parameters of male and female patients were then compared. It was found that the gender differences in the CLZ, NCLZ and total concentrations persisted irrespective of how long patients had been prescribed the CLZ (all P < 0.001).

Second, when subjects were divided into those <40 years and those ≥ 40 years old, significant differences in dosage (P = 0.003) and dosage per kg (P = 0.001) were found, but no significant differences between any CLZ plasma parameters were demonstrated.

Third, we compared CLZ dosage and plasma concentrations between smoking and nonsmoking male patients with schizophrenia (also shown in Table 2). While patients who smoked were on higher absolute and relative doses of CLZ, there were no significant differences in blood concentrations, although a trend towards higher median of NCLZ in smokers than that in nonsmokers (P = 0.073) was observed.

Correlations between dosage (mg day−1) and clozapine concentrations

Significant positive correlations between CLZ daily dose/body weight and plasma CLZ concentrations (Spearman r = 0.264, P < 0.001), NCLZ concentrations (Spearman r = 0.420, P < 0.001), the sum concentrations (Spearman r = 0.322, P < 0.001) and the NCLZ/CLZ ratio (Spearman r = 0.151, P < 0.05) were observed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation between clozapine dosage (mg day−1 kg−1) and plasma clozapine concentrations (Spearman correlations)

| All samples | Male (n = 116) | Female (n = 77) | <40 years (n = 82) | ≥40 years old (n = 111) | Male smokers (n = 50) | Male non-smokers (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLZ (ng ml−1) | r = 0.264** | 0.352** | 0.120 | 0.365** | 0.124 | 0.371** | 0.268* |

| NCLZ (ng ml−1) | r = 0.420** | 0.485** | 0.310** | 0.449** | 0.358** | 0.505** | 0.374** |

| Sum (ng ml−1) | r = 0.322** | 0.410** | 0.177 | 0.400** | 0.203** | 0.418** | 0.327** |

| NCLZ/CLZ | r = 0.151* | 0.132 | 0.267** | 0.061 | 0.214* | 0.058 | 0.148 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level. CLZ, Clozapine; NCLZ, norclozapine.

The correlational analyses were also performed separately in male and female patients and showed significant correlations between daily dose/body weight with CLZ, NCLZ, and sum in males, and with NCLZ and the NCLZ/CLZ ratio in female patients.

When we examined the sample divided by age, it was found that for younger patients there were significant correlations between daily dose/body weight and plasma parameters for CLZ, NCLZ and sum, but not with the ratio. For older patients, significant correlations were present for NCLZ, sum and the ratio, but not with CLZ.

When the analyses were performed in smokers and nonsmokers separately, CLZ, NCLZ and their sum were positively correlated with dose/weight in both smokers and nonsmokers, but there were no significant correlations between dose/weight and NCLZ/CLZ ratio in either group.

Effects of concomitant drugs on CLZ concentrations

As stated in Subjects and methods, among 193 cases, 22 (11.4%) received benzodiazepines and 26 (13.5%) received anticholinergic agents (mostly benzhexol hydrochloride 2–4 mg day−1). We made comparisons of CLZ parameters between those who received concomitant drugs and those who did not, and found no significant differences in any parameters (all P ≥ 0.15).

Discussion

Steady-state concentrations and dose–level correlations

The present study, using a naturalistic design, reports on the variability and determinants of steady-state (at same dose for at least 7 days) plasma concentrations of CLZ and its metabolite NCLZ in 193 Chinese patients with schizophrenia. The daily doses of CLZ ranged from 75 to 600 mg. Consistent with most studies involved in different ethnic backgrounds [4–6, 8, 12], we found that steady-state CLZ concentrations varied greatly for a given dose. In our study, at a dose of 400 mg daily, steady-state concentrations varied up to 8.7-fold.

The mean CLZ plasma concentrations reported in this population were higher than those reported by Haring et al.[4], who analysed 148 Austrian patients taking oral doses of CLZ of 12.5–700 mg day−1 (mean 281.0 mg, SD ± 141.0) and reported CLZ concentrations of 160.1 ± 9.9 ng ml−1 (mean ± SEM) compared with 426.5 ± 20.4 ng ml−1 (calculated as mean ± SEM) in our study. Our NCLZ/CLZ ratio (0.49 ± 0.22) was lower than the 0.8 reported by Volpicelli et al.[31], but similar to the values reported by Lovdahl et al.[32] and Perry et al.[22].

We also found significant positive correlations between the daily dose of CLZ and the various CLZ plasma concentrations in our total sample of 193 subjects. This is consistent with most prior studies, either naturalistic [4, 5, 12, 31, 33] or based on a controlled prospective design [6, 34]. However, our Spearman r-values (rclozapine = 0.264, P < 0.01; rnorclozapine = 0.42, P < 0.01; rsum = 0.322, P < 0.01) are lower than those in most previous reports, in which correlations ranged from 0.4 (P< 0.002) [6] to 0.7 [35]. One possible explanation for such discrepancies could be the vastly different patient numbers in the various studies (22–248 patients) or, as suggested by Hasegawa et al.[6], the variable degree of compliance with CLZ may contribute to altering the strength of the relationship between dose and plasma concentrations.

Interestingly, we observed that CLZ dose–plasma concentration correlations were significant in males (Spearman rclozapine = 0.352, P < 0.01), but not in females (Spearman rclozapine = 0.120, P >0.05). This finding differs from that of Palego et al.[16], who conversely found a significant correlation in women but not in men.

Regarding smoking behaviour, significant correlations were found in both smoking and nonsmoking patients. The NCLZ/CLZ ratio, which is considered an index of CLZ metabolism, was not correlated to dose in either smokers or nonsmokers.

Effect of patient-related factors on plasma parameters

We compared plasma concentrations divided by dose/weight using the Mann–Whitney nonparametric statistical test in three different subgroups of patients, as previously reported by Haring et al.[4] and Palego et al.[16]. In our sample, an increase in CLZ and NCLZ plasma concentrations was observed in women (about +18–26%) compared with men, a figure slightly lower than the ∼ +35–50% reported in much of the literature, for CLZ only [4, 5] and for CLZ and its metabolites combined [12, 20, 36]. In contrast, Perry et al.[22] and Hasegawa et al.[6] found no significant difference in CLZ plasma parameters between males and females.

As Fabrazzo et al.[23] have suggested that the gender differences occur only after 4–6 weeks and disappear after 24 weeks of treatment, we examined patients on CLZ between 6 and 24 weeks and >24 weeks, and again compared the plasma CLZ parameters of male and female patients in those two groups defined by duration of treatment. We found that the gender differences in CLZ, NCLZ and the total concentrations still existed after 24 weeks of CLZ treatment.

A number of other studies have reported higher plasma CLZ concentrations in females even after dose and weight adjustment [5, 13–18]. This could, in part, reflect a lower CLZ clearance rate in females and would be consistent with lower CYP1A2 activity in females [37, 38], although such differences have not been confirmed in some reports [39]. The effect of body fat composition on trough plasma drug concentrations should also be considered [40]. A higher body fat content could be associated with a higher volume of distribution (per unit body weight) and, hence, an increased CLZ half-life in females. This would, in turn, reduce the group difference between peak and trough plasma CLZ concentrations at steady state. Females, whose CLZ dose is adjusted according to clinical observation, may therefore have similar mean steady-state plasma CLZ concentrations, but higher trough concentrations than males. A similar argument applies to explain the (weak) positive correlation between body weight and plasma CLZ. The effect of weight on metabolic activity (via liver size) is expected to be in the opposite direction to its effect on volume of distribution. Thus, a direct relationship between plasma CLZ and weight suggests that the effect on volume of distribution is more pronounced than that on clearance. A higher volume would cause a longer plasma half-life and consequently less fluctuation in plasma CLZ concentrations (i.e. lower Cmax and higher Ctrough).

The impact of any age-related change in renal function on the total clearance of CLZ would be expected to be minimal, as renal excretion accounts for only a small proportion of the drug's clearance [13]. The findings of studies of correlations between plasma CLZ concentrations and age have been inconsistent. Some authors have observed CLZ [5] or both CLZ and NCLZ plasma concentrations [12] to increase with age. We found no differences in CLZ plasma parameters in patients ≥ 40 years old compared with those <40 years, which is consistent with Pagelo et al.[16]. Similarly, Perry et al.[15] found no statistically significant relationship between age and plasma CLZ concentrations.

Smoking habits seem possibly to exert some influence on plasma concentrations in this population. The NCLZ concentration showed an upward trend in smokers, but neither CLZ, sum or NCLZ/CLZ ratio showed significant differences. Our finding does not replicate reports of lowered CLZ concentrations in smokers [4, 5, 11, 24], but it is of interest that we found that the dosage and dosage/body weight of CLZ in male smokers were both significantly higher that those of nonsmokers, suggesting that smokers may require higher doses of the drug to gain clinical benefit.

In conclusion, the current study reports CLZ, NCLZ plasma concentrations, total analytes and their ratio (NCLZ/CLZ) obtained in 193 naturalistically recruited Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia treated with CLZ monotherapy. The concentrations which we observed were similar to those reported by western researchers. Plasma CLZ concentrations/kg body weight varied up to eightfold for a given dose in our Chinese population. Gender appeared to exert a significant influence on CLZ plasma parameters, with female patients showing higher plasma concentrations. However, no significant effects of age or smoking behaviour on CLZ concentrations were observed in our sample.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Jiang Z. [Progress of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia] Chin J Psychiatry. 1999;32:121–3. (Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang YL, Jiang ZN, Zhai YM, Wu YM. Screening and evaluation of predictive factors among refractory schizophrenics treated with clozapine [Article in Chinese] Chin J Psychiatry. 1997;30:157–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang YL. Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. In: Cai ZJ, Weng YZ, Tang YL, editors. Schizophrenia: from Biology to Treatments. 1. Beijing: Science Press; 2000. pp. 214–27. (Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haring C, Meise U, Humpel C, Saria A, Fleischhacker WW, Hinterhuber H. Dose-related plasma levels of clozapine: influence of smoking behaviour, sex and age. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99(Suppl.):S38–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00442557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haring C, Fleischhacker WW, Schett P, Humpel C, Barnas C, Saria A. Influence of patient-related variables on clozapine plasma levels. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1471–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.11.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasegawa M, Gutierrez-Esteinou R, Way L, Meltzer HY. Relationship between clinical efficacy and clozapine concentrations in plasma in schizophrenia: effect of smoking. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu HC, Chang WH, Wei FC, Lin SK, Jann MW. Monitoring of plasma clozapine levels and its metabolites in refractory schizophrenic patients. Ther Drug Monit. 1996;18:200–7. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199604000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang WH, Lin SK, Lane HY, Hu WH, Jann MW, Lin HN. Clozapine dosages and plasma drug concentrations. J Formos Med Assoc. 1997;96:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chetty M, Miller R, Moodley SV. Smoking and body weight influence the clearance of chlorpromazine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:523–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00196109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai HD, Seabolt J, Jann MW. Smoking in patients receiving psychotropic medications: a pharmacokinetic perspective. CNS Drugs. 2001;15:469–94. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seppala NH, Leinonen EV, Lehtonen ML, Kivisto KT. Clozapine serum concentrations are lower in smoking than in non-smoking schizophrenic patients. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1999;85:244–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1999.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane HY, Chang YC, Chang WH, Lin SK, Tseng YT, Jann MW. Effects of gender and age on plasma levels of clozapine and its metabolites: analyzed by critical statistics. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:36–40. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaber G, Stevens I, Gaertner HJ, Dietz K, Breyer-Pfaff U. Pharmacokinetics of clozapine and its metabolites in psychiatric patients: plasma protein binding and renal clearance. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:453–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerling M, Merle Y, Mentre F, Mallet A. Population pharmacokinetics of clozapine evaluated with the nonparametric maximum likelihood method. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:447–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.t01-1-00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry PJ, Bever KA, Arndt S, Combs MD. Relationship between patient variables and plasma clozapine concentrations: a dosing nomogram. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:733–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palego L, Biondi L, Giannaccini G, Sarno N, Elmi S, Ciapparelli A, Cassano GB, Lucacchini A, Martini C, Dell'Osso L. Clozapine, norclozapine plasma levels, their sum and ratio in 50 psychotic patients: influence of patient-related variables. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:473–80. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane HY, Jann MW, Chang YC, Chiu CC, Huang MC, Lee SH, Chang WH. Repeated ingestion of grapefruit juice does not alter clozapine's steady-state plasma levels, effectiveness, and tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:812–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuss H. Proceedings of VII World Conference on Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics; 15–20 July 2000, Florence, Italy. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2000. TDM of clozapine: influence of co-medication; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szymanski S, Lieberman J, Pollack S, Kane JM, Safferman A, Munne R, Umbricht D, Woerner M, Masiar S, Kronig M. Gender differences in neuroleptic nonresponsive clozapine-treated schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:249–54. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jann MW, Liu HC, Wei FC, Chang WH. Gender differences in plasma clozapine levels and its metabolites in schizophrenics patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:489–95. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackenheil M, Brau H, Burkhart A, Franke A, Pacha W. Arzneimittelforschung. 1976;26:1156–8. [Antipsychotic efficacy in relation to plasma levels of clozapine (author's translation)] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry PJ, Miller DD, Arndt SV, Cadoret RJ. Clozapine and norclozapine plasma concentrations and clinical response of treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:231–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabrazzo M, Esposito G, Fusco R, Maj M. Effect of treatment duration on plasma levels of clozapine and N-desmethylclozapine in men and women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:197–200. doi: 10.1007/BF02245621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao JP, Chen YG, Chen JD, Li HD, Peng WX. Pharmacokinetic studies of clozapine: relationship of dosage and concentration and other factors [Article in Chinese] Chin J Psychiatry. 1996;29:220–3. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng WX, Li HD, Xu SW, Guo ZG. The effect of smoking and sex on pharmacokinetics of clozapine and norclozapine [Article in Chinese] Chinese J Pharmacy. 1997;32:541–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ, Frankenburg FR, Kando J, Volpicelli SA, Flood JG. Serum levels of clozapine and norclozapine in patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:820–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.6.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. DSM-IV. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ereshefsky L, Watanabe MD, Tran-Johnson TK. Clozapine: an atypical antipsychotic agent. Clin Pharm. 1989;8:691–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weigmann H, Hiemke C. Determination of clozapine and its major metabolites in human serum using automated solid-phase extraction and subsequent isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection. J Chromatogr. 1992;583:209–16. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li WB, Qin YF, Zhai YM, Guo GX, Xu MJ. Detection of Clozapine, tricyclic antidepressants and their desmethyl metabolites in serum by high-performance liquid chromatography [Article in Chinese] Chin J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;15:369–73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volpicelli SA, Centorrino F, Puopolo PR, Kando J, Frankenburg FR, Baldessarini RJ, Flood JG. Determination of clozapine, norclozapine, and clozapine-N-oxide in serum by liquid chromatography. Clin Chem. 1993;39:1656–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovdahl MJ, Perry PJ, Miller DD. The assay of clozapine and N-desmethylclozapine in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. Ther Drug Monit. 1991;13:69–72. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centorrino F, Baldessarini RJ, Kando JC, Frankenburg FR, Volpicelli SA, Flood JG. Clozapine and metabolites: concentrations in serum and clinical findings during treatment of chronically psychotic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1994;14:119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackenheil M. Clozapine–pharmacokinetic investigations and biochemical effects in man. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1989;99(Suppl.):S32–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00442556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bondesson U, Lindstrom LH. Determination of clozapine and its N-demethylated metabolite in plasma by use of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry with single ion detection. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;95:472–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00172957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szymanski S, Masiar S, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Geisler S, Pollack S, Kane J, Lieberman J. Clozapine response in treatment-refractory first-episode schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1994;35:278–80. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)91259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Relling MV, Lin JS, Ayers GD, Evans WE. Racial and gender differences in N-acetyltransferase, xanthine oxidase, and CYP1A2 activities. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;52:643–58. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tantcheva-Poor I, Zaigler M, Rietbrock S, Fuhr U. Estimation of cytochrome P-450 CYP1A2 activity in 863 healthy Caucasians using a saliva-based caffeine test. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:131–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welfare MR, Aitkin M, Bassendine M, Daly A. Treatment-resistance to clozapine in association with ultrarapid CYP1A2 activity and the C–>A polymorphism in intron 1 of the CYP1A2 gene: effect of grapefruit juice and low-dose fluvoxamine. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:367–75. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rostami-Hodjegan A, Amin AM, Spencer EP, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Flanagan RJ. Influence of dose, cigarette smoking, age, sex, and metabolic activity on plasma clozapine concentrations: a predictive model and nomograms to aid clozapine dose adjustment and to assess compliance in individual patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:70–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000106221.36344.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]