Abstract

What is already known about this subject

Previous studies have pointed out the question of effective training and information for health professionals on adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

This lack of training is known to induce inadequate use of drugs and noncompliance of patients.

What this study adds

Our study was the first to evaluate the perceived risk of ADRs among young medical students and to investigate the impact of university pharmacology courses on their perception of this risk.

The aim of our study was not to assess a definite level of perception of risk for the different drug classes but to determine whether the perceived risk of ADRs differs after attending pharmacology courses.

Our results show that the pharmacological training allows young medical students to be aware of potentially serious ADRs, especially related to drugs considered as relatively safe, such as NSAIDs and aspirin.

Aims

To investigate how adverse drug reactions (ADRs) to several classes of drugs are perceived by young medical students before and after a 1 year pharmacology course.

Methods

The whole cohort of 92 medical students (63 females and 29 males) was questioned during their third year. A visual analogue scale was used to define a score (ranging from 0 to 10) of perceived risk of ADRs associated with each drug class before and at the end of the pharmacological training period.

Results

Before the pharmacology course, hypnotics were ranked as the most dangerous drugs by the medical students, followed by antidepressants and anticoagulants. Contraceptive pills were listed in the last position. After pharmacological training, antidepressants moved into the first position, followed by anticoagulants and hypnotics. When all different drug classes were taken as a whole, the mean (±SD) of median scores of the perceived risk were 4.8 (±1.3) before and 5.8 (±1.5) at the end of the pharmacology course (P< 0.0001). Except for antidiabetics, antihypertensive drugs, tranquillizers, corticosteroids and hypnotics, the perceived risk significantly increased after the pharmacology course for the other drugs. The highest increases were observed for contraceptive pills (+104%, P < 0.01), NSAIDs (+86%, P < 0.01) and aspirin (+56%, P < 0.01).

Conclusions

Pharmacological training allows young medical students to be aware of potentially serious ADRs associated with drugs, in particular with drugs considered relatively safe (such as NSAIDs and aspirin) by nonhealth professionals.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, medical students, pharmacovigilance, risk, social pharmacology

Introduction

Previous studies performed by our group have found major differences in the perception of risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) between health and nonhealth professionals [1]. For example, anticoagulants were ranked as the most dangerous drugs by health professionals, whereas sleeping pills were the first drug with a risk of ADRs for the general public. A recent study [2] has shown that patients' knowledge of risks associated with their medication was frequently inaccurate and at best inconsistent. We also found differences in the perception of risks of gastrointestinal ADRs among physicians according to their medical specialization [3]. Rheumatologists systematically considered NSAIDs as less harmful than general practitioners and gastroenterologists. It was also reported that many rheumatologists wrongly believed that the risk of adverse events disappeared in patients at stable drug dosage for many months [4]. In fact, personal factors, such as the year the doctors graduated, the place where they worked or their awareness of ADRs, could affect their perception of the risk of ADRs [5]. These studies underline the role of socially generated irrational factors in drug knowledge and in the perception of their effects.

Following this topic of research in Social Pharmacology [6, 7], the aim of the study was to investigate how ADRs of several drug classes are perceived by young medical students before and after a 1 year pharmacological course.

Methods

The whole cohort of 92 medical students taking the class (63 females and 29 males, average age: 21 years (SD 1.2)) was questioned during their third year at the Toulouse Faculty of Medicine, France. The students had never studied pharmacology before. The pharmacological training included general pharmacology courses (mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, drug interaction, clinical trials, pharmacovigilance, pharmacodependence and pharmacoepidemiology) and specialized pharmacology courses (autonomic, cardiovascular, renal, neuropsychotropic, endocrine drugs etc.). The course consisted of lectures (58 h) and training (28 h). A visual analogue scale was used to define a score of perceived risk of ADRs associated with each drug class before (October 2004) and after (May 2005) taking the course in pharmacological training. The drug classes evaluated were: antibiotics, anticoagulants, antidepressants, aspirin, contraceptive pills, corticosteroids, drugs for arterial hypertension, drugs for diabetes (other than insulin), hypnotics, hypocholesterolaemic drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), drugs for postmenopausal hormone replacement and tranquillizers. For each drug class, the perceived risk of ADRs was assessed by measuring the distance between the left extremity of the scale (equal to zero) and the mark made by the student. Since each scale measured 10 cm, the perceived risk of ADRs could be considered as a quantitative score ranging from 0 to 10. Finally, when the different drug classes were taken as a whole, a total score (i.e. the mean value of the different individual values) was calculated at both assessments (October 2004 and May 2005). For the different drug classes, results are shown as median values (25th−75th centiles). Precourse and postcourse scores were compared using a signed ranked Wilcoxon test.

Results

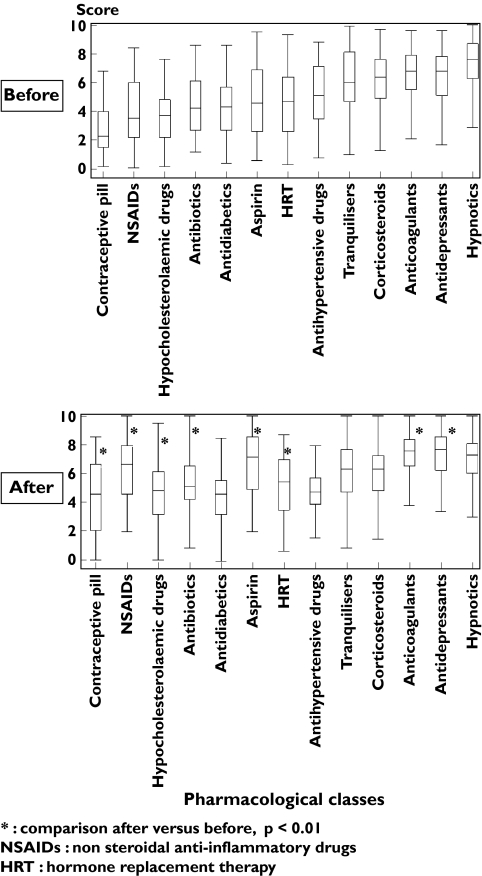

Figure 1 shows the drugs ranked according to the median value (25th−75th centiles) of perceived risk of ADRs on the visual analogue scales. Before the pharmacology course, hypnotics (7.6, 6.3–8.7) were ranked as the most dangerous drugs by medical students, followed by antidepressants (6.8, 5.1–7.9) and anticoagulants (6.5, 5.5–7.9). Contraceptive pills (2.3, 1.5–4.0) were listed in the last position. After pharmacological training, the three most ‘dangerous’ were the same, but antidepressants moved up to the first position.

Figure 1.

Median scores of perceived risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) on visual analogue scales (25th−75th centiles) by the medical students before vs. after the pharmacology course

When all different drug classes were taken as a whole, the mean (±SD) of median scores of the perceived risk were 4.8 (±1.3) before the course and 5.8 (±1.5) at the end of the pharmacology course (P< 0.0001).

Except for antidiabetics, antihypertensive drugs, tranquillizers, corticosteroids and hypnotics (Figure 1), the perceived risk significantly increased for every other class after taking the pharmacological course. The highest increases were observed for contraceptive pills (+104%, P < 0.01) followed by NSAIDs (+86%, P < 0.01) and aspirin (+56%, P < 0.01). In spite of this increase, contraceptive pills remained in the last position after pharmacological courses.

Discussion

Previous studies have investigated the opinion and awareness of health professionals concerning the risk of ADRs associated with various drug classes. They have pointed out the question of effective training and information to health professionals on pharmacovigilance and ADRs. The lack of training is known to induce inadequate use of drugs and noncompliance of patients [1–3]. Our study was the first to evaluate the perceived risk of ADRs in young medical students and to investigate the impact of university pharmacology courses on their perception of risk. Our aim was not to assess a definite level of perception of risk for the different drug classes but to determine whether the perceived risk of ADRs differs after pharmacology courses.

The opinion of the young students was assessed twice, just before the first course of medical pharmacology and at the end of the last course of pharmacology during the same university year (i.e. 7 months later). At the beginning of that university year, the students had never studied pharmacology. During the first assessment, they ranked anti-inflammatory drugs in eighth position, aspirin in twelfth position. They considered that contraceptive pills were the least dangerous drugs and that hypnotics, anticoagulants and antidepressants were the most dangerous. Clearly, they underestimated the risk associated with NSAIDs and aspirin, although these drugs were found to be the pharmacological class most frequently involved in hospital admissions due to an adverse effect of a prescribed drug [8].

Our findings can be compared with values found by Bongard et al.[1], using the same methodology. Their study investigated differences in the perceived risk of ADRs between health professionals (general practitioners, pharmacovigilance professionals and pharmacists) and nonhealth professionals, the public at large so to speak. The ‘hit-parade’ established by young students without knowledge about pharmacology was similar to that established by nonhealth professionals who ranked psychotropics in the first position and did not seem aware of potentially serious ADRs related to NSAIDs or aspirin. One could suggest that these drugs are widely used by the whole family without perceiving the danger since they can be easily obtained (over the counter for ibuprofen and aspirin). Another interesting result of the present study is that pharmacological course increased the global perception of risk (global median score: 4.8 at the beginning of the study vs. 5.8 at the end, P < 0.0001). When compared with the study of Bongard et al.[1], it is interesting to underline, first, that medical students before pharmacological training gave the lowest risk value (4.8) when compared with other previously studied populations: pharmacists (6.1), pharmacovigilance professionals (5.5), nonhealth professionals (5.4) and general practitioners (5.3). Secondly, at the end of the pharmacological course, medical students become more cautious and their score placed them in second position, between pharmacists and pharmacovigilance professionals.

For the students, the most important increases concerned contraceptive pills (+104%), NSAIDs (+86%) and aspirin (+56%), i.e. drugs considered among the least dangerous before the course. In spite of this increase, it can be noted that contraceptive pills remained in the last position, thus still associated with the lowest perceived risk. Conversely, the perception of risk tended to decrease for drugs such as antihypertensive drugs or hypnotics.

Besides the influence of the pharmacology course, other important factors, like information in the various media, have to be considered to explain the difference in the perception of risk. For example, the increase in perceived risk where NSAIDs are concerned could also be due to information published by the health authorities and the media about cardiovascular risks related to rofecoxib [9, 10] while the study was being conducted. Compared with health professionals in a previous study [1], students have a higher perception of risks linked to antidepressants and postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. This was the case even for the first assessment. However, the study of Bongard et al.[1] was performed in 2000 and the present one in 2004–05. Between the two periods, the media fully reported the risk of cancer linked to postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy [11] and highlighted suicide attempts by adolescents linked to antidepressants [12].

In conclusion, the present study shows that pharmacological training allows young medical students to be aware of potentially serious ADRs associated with drugs, especially for drugs considered as relatively safe by nonhealth professionals (such as NSAIDs and aspirin). It also corroborates the possible effect of the media on the perception of risks related to drugs.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Bongard V, Ménard-Taché S, Bagheri H, Kabiri K, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL. Perception of the risk of adverse drug reactions. Differences between health professionals and non-health professionals. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:433–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullen G, Kelly E, Murray FE. Patients' knowledge of adverse reactions to current medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:232–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montastruc JL, Bongard V, Lapeyre-Mestre M. Perception of the risk of gastrointestinal adverse drug reactions with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including coxibs): differences among general practitioners, gastroenterologists and rheumatologists. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:685–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0648-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grove ML, Hassel AB, Hay EM, Shadforth MF. Adverse reactions to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in clinical practice. Q J Med. 2001;94:309–19. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.6.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cosentino M, Leoni O, Oria C, Michielotto D, Massino E, Lecchini S, Frigo G. Hospital-based survey of doctors' attitudes to adverse drug reactions and perception of drug-related risk for adverse reaction occurrence. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 1999;8:S27–S35. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1557(199904)8:1+<s27::aid-pds407>3.3.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montastruc JL. Social pharmacology: a new topic in clinical pharmacology. Thérapie. 2002;57:420–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngoundo Mbongue TB, Sommet A, Pathak A, Montastruc JL. ‘Medicamentation’ of society, non-diseases and non-medications: a point of view from social pharmacology. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:309–13. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0925-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pouyanne P, Haramburu F, Imbs JL, Bégaud B. Admissions to hospital caused by adverse reactions: cross sectional incidence study. Br Med J. 2000;320:1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7241.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medical Agency. Press release. EMEA 6 October 2004 Statement following withdrawal of Vioxx (Rofecoxib) Website http://www.emea.eu.int. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anonymous. How to avoid future Vioxx-type scandals. Prescribe Int. 2005;14:115–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Medical Agency. CHMP – EMEA public statement on recent publications regarding hormone replacement therapy 3 December 2003. Website: http://www.emea.eu.int.

- 12.European Medical Agency. CHMP-EMEAQuestions and answers on paroxetineRevised version following the CHMP meeting of 8 December 2004. Website: http://www.emea.eu.int.