After a gestation period of 2 years, a new Adverse Effects Methods Group has recently been registered as part of the Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.org/contact/mwgfield.htm). This is the culmination of a process that started with a meeting of interested parties in Oxford in August 2005 and was followed by informal meetings of a working party and eventually an open meeting at the Dublin Colloquium of the Collaboration in October 2006. The main objectives of the Group are to develop and implement methods for systematic reviews of the adverse effects of therapeutic interventions. Although adverse drug reactions will form a major thrust of this activity, all therapeutic interventions, including devices and surgical interventions, come within the Group's remit. The co-conveners are Su Golder (spg3@york.ac.uk), Andrew Herxheimer (a.herxheimer@ntlworld.com), and Yoon Loke (y.loke@uea.ac.uk); anyone who wants to participate, either actively or passively, should get in touch with them.

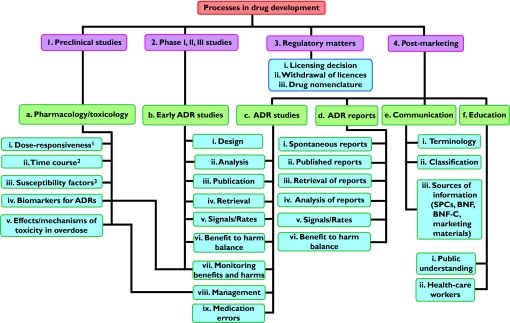

Part of the remit of the working party was to prepare a plan for the work of the Group, including formulation of policy and research proposals. This plan was to relate to systematic reviews, but during our discussions it emerged that it would be useful to formalize an agenda for general types of research on adverse drug reactions. Such an agenda is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1 and examples of possible research projects are listed in Table 1[1–9]. I invite comments on this agenda.

Figure 1.

Potential headline topics for research in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); 1 + 2 + 3 = the DoTS classification of adverse drug reactions [1], which applies to ADRs at all stages of detection, not merely during the preclinical phase, as shown

Table 1.

Examples of potential research projects in adverse drug reactions (ADRs)

| Heading | Examples |

|---|---|

| Pharmacology/toxicology | 1.Constructing a database of published dose-response curves in ADRs (in vitro and in vivo): |

| •in order to analyse their characteristics (e.g. maximal efficacy, slope) | |

| •the use of in vitro data to predict in vivo outcomes | |

| 2.Defining the time-courses of ADRs | |

| 3.Defining susceptibility factors in patients | |

| 4.Developing and using biomarkers of adverse effects | |

| 5.Effects of overdose and methods of management [1 + 2 + 3 → DoTS classification of adverse drug reactions [1]] | |

| Regulation | How drug regulatory decisions should be made |

| •licensing decisions | |

| •withdrawing drugs after llicensing | |

| Naming medicines | |

| Marketing | How information about ADRs is disseminated |

| •Summaries of Product Characteristics (SPCs) | |

| •advertising | |

| Communication & education | Methods of communicating with health-care professionals [2] and the public: |

| •the nature of risk | |

| •perceptions of risks [3] | |

| •the actual risks and their relevance to clinical practice | |

| •the nature of the balance of benefit and harm | |

| Study design | Reporting methods Which types of design are best for eliciting particular types of ADR (e.g. cohort studies, case-control studies, n-of-1 studies, RCTs) |

| Analysis | Teleoanalysis – how best to combine information from many different types of evidence (RCTs, observational studies, case series, anecdotes) When different types of evidence are relevant Data mining techniques [4] |

| Terminology & classification | Developing classification systems [5] Dictionaries – using standard terminology [6] |

| Publication | Developing CONSORT-like statements [7] |

| Review | The use of anecdotes and spontaneous reports [8] Systematic review (including narrative review, meta-analysis, and teleoanalysis) Methods of searching for published information [9] Indexing databases |

Adverse drug reactions are among the constant preoccupations of clinical pharmacologists and commonly feature in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology[10]. This issue is no exception, and papers on adverse reactions that it contains illustrate different aspects of the research agenda – susceptibility factors, mechanisms of adverse reactions, and perceptions of risks and the effects of education.

The need to elucidate individual susceptibility factors is illustrated by a study of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the catabolism of pyrimidines, such as fluorouracil [11]. Deficiency of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase is a susceptibility factor for 5-fluorouracil toxicity. However, it is not known if polymorphisms in the gene for the enzyme influence the risk in individuals with normal enzyme activity. In 131 patients with fluorouracil toxicity dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity was significantly lower than in 185 unselected patients with cancers, but there was extensive overlap between the groups. Furthermore, only two of 93 patients screened carried the IVS14 + 1G > A mutation; although both had had severe toxicity, so had four other patients without the mutation. Since dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency explains only part of the susceptibility to fluorouracil, the search for other susceptibility factors will have to continue.

Elucidation of the mechanisms of adverse effects can be important in determining methods of management. Overdosage of venlafaxine can cause cardiac arrhythmias through mechanisms that are unclear. In a retrospective study of 235 young adults described in this issue of the Journal there was a weak but significant relation between the reported dose and the QTc interval [12]. However, there were only three cases of arrhythmias and none of torsade de pointes. The authors suggested that the effects on heart rate and blood pressure were consistent with noradrenergic potentiation and also speculated about a possible effect of venlafaxine on sodium channels. However, they did not speculate about possible methods of management.

Patients do not always have the same perceptions about the risks of using drugs as health professionals, and there are also differences among the health professionals themselves [3]. This has been illustrated in a study of French medical students reported in this issue of the Journal, as has the effect of education [13]. Before a pharmacology course the students ranked hypnotics as the most dangerous drugs, followed by antidepressants and anticoagulants, similar to the perception of non-health professionals [3]. After the course the order changed to antidepressants, anticoagulants, and hypnotics. Their perceptions of the risks of other drugs also changed. These results reinforce, if reinforcement were necessary, the importance of education in improving prescribing [14].

Finally, a completely different type of adverse effect features in a commentary in this issue of the Journal by Dear & Webb [15]. It is the adverse effect on prescribing of the phenomenon that has been christened ‘disease mongering’, a form of medicalization [16] that was the subject of a series of articles in PLoS Medicine last year. The term seems to have been introduced by the American journalist Lynn Payer [17] and popularized by, among others, the Australian journalist Ray Moynihan [18, 19], although the related term ‘nostrum-monger’ was in use as early as the beginning of the 18th century. Payer defined disease mongering as ‘trying to convince essentially well people that they are sick, or slightly sick people that they are very ill’. Examples include the conversion of shyness into Social Anxiety Disorder, premenstrual symptoms into Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder, and various sexual difficulties that some women experience, such as failure to achieve regular orgasms, into Female Sexual Dysfunction. The marketing of these conditions by pharmaceutical companies leads to unnecessary prescribing and potential adverse effects, and Dean & Webb suggest that doctors and patients are complicit in the process.

Several other aspects of research into adverse drug reactions were included in the special issue of the Journal that appeared earlier this year [10]. It is to be hoped that the activities of the new Cochrane Adverse Effects Methods Group will lead to more material for similar issues in the future.

Acknowledgments

The ideas expressed in Figure 1 and Table 1 were generated after discussions in the working party of the Adverse Effects Methods Group of the Cochrane Collaboration, to all of whom I am grateful: Deborah Ashby, Stephen Evans, Su Golder, Andrew Herxheimer, Yoon Loke, and Saad Shakir.

References

- 1.Aronson JK, RE Ferner. Joining the DoTS. New approach to classifying adverse drug reactions. BMJ. 2003;327:1222–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferner RE, Aronson JK. Communicating information about drug safety. BMJ. 2006;333:143–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7559.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson JK. Risk perception in drug therapy. Br. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:135–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02739_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauben M, Madigan D, Gerrits CM, Walsh L, Van Puijenbroek EP. The role of data mining in pharmacovigilance. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:929–48. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Clarification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Saf. 2005;28:851–70. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown EG. Effects of coding dictionary on signal generation: a consideration of use of MedDRA compared with WHO-ART. Drug Saf. 2002;25:445–52. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200225060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ioannidis JP, Evans SJ, Gotzsche PC, O'Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, D Moher. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson JK. Unity from diversity: the evidential use of anecdotal reports of adverse drug reactions and interactions. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11:195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golder S, McIntosh HM, Loke Y. Identifying systematic reviews of the adverse effects of health care interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions – no farewell to harms. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:131–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magné N, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Cals L, Renée N, Formento JL, Francoual M, Milano G. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase activity and the IVS14 + 1G > A mutation in patients developing 5FU-related toxicity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:237–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell C, Wilson AD, Waring WS. Cardiovascular toxicity due to venlafaxine poisoning in adults: a review of 235 consecutive cases. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:192–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durrieu G, Hurault C, Bongard V, Damase-Michel C, Montastruc JL. Perception of risk of adverse drug reactions by medical students: influence of a 1 year pharmacological course. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:233–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:487–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dear JW, Webb DJ. Disease mongering – a challenge for everyone involved in healthcare. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:122–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aronson JK. When I Use a Word … Medicalization. BMJ. 2002;324:904. [Google Scholar]

- 17.L Payer. How Doctors, Drug Companies, and Insurers are Making you Feel Sick. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. Disease-Mongers. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering. BMJ. 2002;324:886–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moynihan R, Cassels A. Selling Sickness. How Drug Companies are Turning us all into Patients. Crows Nest, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin; 2005. [Google Scholar]