Abstract

What is already known about this subject

In the UK prescribing-related errors are common.

Poor prescribing and prescribing errors result in significant patient morbidity and mortality.

In hospital, junior doctors are responsible for a significant number of prescribing errors.

What this study adds

Only 8% of foundation year (FY) 1 doctors rate their knowledge of clinical pharmacology as good and 30% as poor or worse.

The majority of FY1 doctors reported themselves confident to prescribe medicines associated with high levels of patient morbidity and mortality.

Potentially avoidable adverse drug reactions and drug interactions were reported by 60–75% of FY1 doctors, many of which were reported to have been avoidable with more extensive undergraduate training.

FY1 doctors would like more focused undergraduate teaching on the avoidance of adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions, together with increased clinical pharmacology and therapeutics in their postgraduate training programme.

Aims

To determine whether, in retrospect, first year foundation (FY1) programme doctors believe that their undergraduate education in Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (CPT) has prepared them to prescribe safely and rationally.

Methods

This was a prospective questionnaire survey. Ninety FY1 doctors, employed in the Aberdeen Teaching Hospitals, participated.

Results

Seventy-one percent of FY1 doctors completed the survey. Thirty percent of respondents rated their knowledge of CPT as poor or worse and only 8% as good; 74% reported having witnessed an adverse drug reaction (ADR) and 55% a drug–drug interaction, a number of which had resulted in patient morbidity or mortality. Many of these events were reported to have been avoidable or predictable with more extensive undergraduate and postgraduate training. Forty-two percent of respondents stated that they had not been taught enough about avoiding ADRs and 60% about avoiding drug–drug interactions during their undergraduate years. Over 75% of respondents reported high levels of confidence for the unsupervised use of warfarin, nonsteroidal analgesics and opiate analgesics. In retrospect, FY1 doctors would like more undergraduate teaching in prescribing for special patient groups, ADRs, drug interactions, together with CPT in their postgraduate teaching programme.

Conclusions

FY1 doctors believe that their undergraduate and postgraduate training in CPT is insufficient to prescribe safely and rationally. This study adds further weight to the call for an increase in the training of junior doctors in the rational and safe use of medicines.

Keywords: adverse drug reactions, clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, foundation programme doctors, patient safety, prescribing, questionnaire

Introduction

The 2001 Audit Commission report A spoonful of sugar and the more recent 2005 Audit Scotland report A Scottish Prescription have raised concerns about the adequacy of undergraduate education in preparing new doctors for the complex task of rational, safe prescribing [1, 2]. Concern has been further highlighted by recent reports from the Healthcare Commission and National Patient Safety Agency suggesting that in the UK approximately 250 000 admissions to hospital occur annually as a result of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and that more than 41 220 medication errors are made each year in English and Welsh hospitals [3, 4]. Since the publication of Tomorrows Doctors[5], there has been progressive integration of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (CPT), the specialty responsible for training doctors in the safe, rational and efficacious use of medicines, into other areas of the undergraduate curriculum with resultant reduction in the amount of time spent teaching undergraduates about prescribing and the perils of pharmacotherapy [6]. The result has been an increasing call in the UK for improvement in medical training to ensure that junior doctors are able to perform the complex task of medicines prescribing safely and rationally [7, 8].

Although few studies have attempted to assess the impact of changes in undergraduate medical curricula on prescribing, it is likely that the reduction in CPT teaching has contributed to the 500% increase in patient deaths due to ADRs since the early 1990s, and the rising incidence of medication errors and ADRs in the UK [9]. While it is difficult to attribute prescribing decisions accurately, in the hospital environment the majority of prescription-related errors are made by junior doctors [10], a finding that supports the targeting of investigation and intervention towards this group.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether doctors coming towards the end of their first year in the foundation programme (FY1) believed that their undergraduate education had adequately prepared them to prescribe safely and rationally, and how in retrospect they would modify their undergraduate and postgraduate training to improve patient safety.

Methods

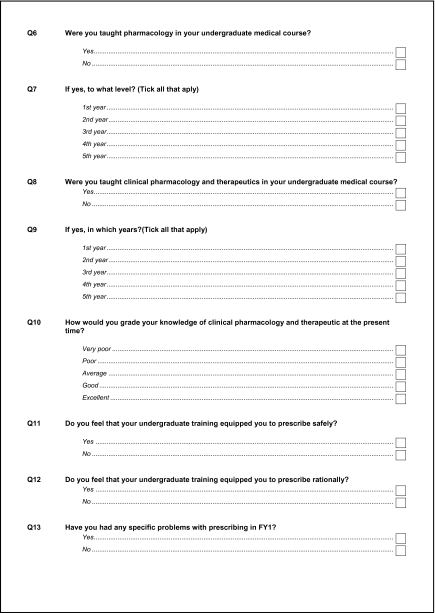

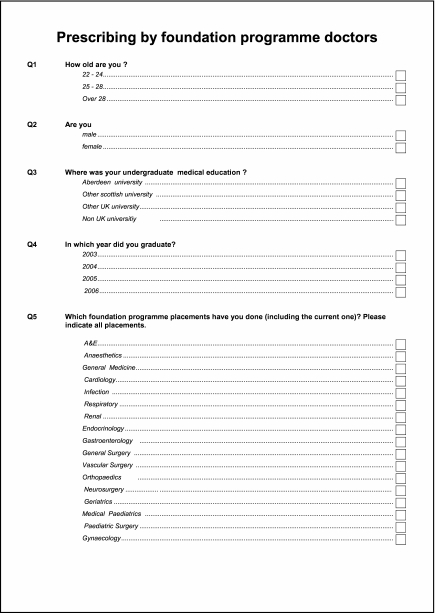

A 44-point questionnaire (see Appendix 1), produced using SNAP software (version 8), was issued to all 90 FY1 doctors employed in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary Teaching Hospitals during April/May 2006. The questionnaire covered demographics, undergraduate and postgraduate training in clinical pharmacology, experience of ADRs and drug interactions since starting work, confidence in drug usage and, in retrospect, any perceived deficiencies in training in clinical pharmacology. Because a doctor either does or does not prescribe, where appropriate the questions were designed to be leading and to elicit a direct yes or no response rather than the usual Likert scale. The questionnaire was then piloted prior to distribution. Participation was voluntary and questionnaires anonymous. Ethical approval was given by Grampian Research Ethics Committee.

Statistics

Data were analysed using SPSS 14 statistics package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). χ2 tests were used to investigate relationships between dichotomous variables.

Results

Demographics

Completed questionnaires were returned by 64 of 90 FY1 doctors employed in Grampian, giving a response rate of 71%. The majority of respondents (81%) had completed their undergraduate medical training locally, 9% in other Scottish Medical Schools, 5% in English Medical Schools and 5% outside the UK system.

Undergraduate CPT

Seventy-seven percent had received undergraduate training in CPT, whereas 17% had not (6% failed to answer this question). Despite this, only 8% of respondents rated their knowledge as good, whereas 30% rated it as poor or very poor. The remainder rated their knowledge as average.

When asked whether their undergraduate teaching had equipped them sufficiently to prescribe safely and rationally, 41% of respondents replied no, and 56% yes (3% failed to answer this question). Respondents were then asked whether they had encountered any problems related to prescribing or medicines use during their FY1 years. A third of respondents (34%) admitted to encountering specific problem areas, including drug toxicity, drug–drug interactions, ADRs, prescribing errors, conflicting advice, prescribing to patients with renal and hepatic impairment, prescribing intravenous medicines and controlled drugs.

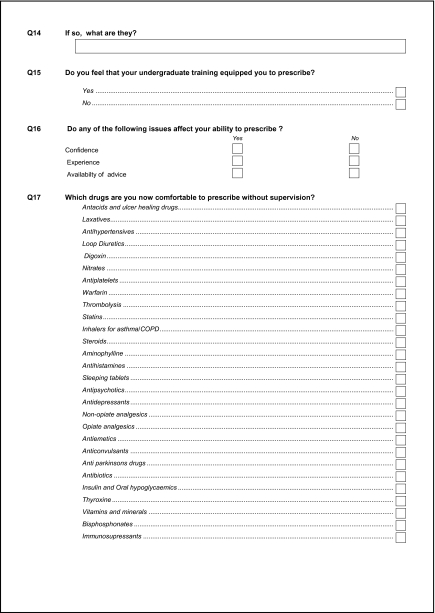

Postgraduate training

To assess development during the FY1 years, respondents were asked to rate their level of confidence when prescribing drugs from a specific list of medicines unsupervised, or when prescribing to special patient groups, such as children. Table 1 reports the number of respondents who rated themselves as confident to prescribe for each of the listed medicines. As might be expected, the number expressing prescribing confidence for low-risk medicines was high, whereas the number for high-risk medicines was low. However, of possible concern were the high numbers who expressed confidence for unsupervised prescribing of nonsteroidal analgesics (92%), opiate analgesics (92%), sleeping tablets (84%) and warfarin (78%). Conversely, the majority of respondents were not confident in prescribing to special patient groups, except the elderly (58%) (Table 2). As might be expected, there was a significant relationship between perceived levels of confidence and attachment to specialist units, with FY1 doctors who had been attached to paediatrics (χ2 35.00, P < 0.001), gynaecology (χ2 4.54, P = 0.03) or gastroenterology (χ2 13.07, P < 0.001) being more confident to prescribe unsupervised to children, pregnant women or patients with liver disease, than those who had not.

Table 1.

Responses to the question ‘Which of the following medicines are you now comfortable to prescribe unsupervised?’

| Drug group | Number |

|---|---|

| Antacids and ulcer healing drugs | 58 (91%) |

| Laxatives | 64 (100%) |

| Antihypertensives | 27 (42%) |

| Loop diuretics | 35 (55%) |

| Digoxin | 23 (36%) |

| Nitrates | 25 (39%) |

| Anti-platelets | 43 (67%) |

| Warfarin | 50 (78%) |

| Thrombolysis | 7 (11%) |

| Statins | 52 (81%) |

| Inhalers for asthma/COPD | 43 (67%) |

| Steroids | 27 (42%) |

| Aminophylline | 16 (25%) |

| Anti-histamines | 53 (83%) |

| Sleeping tablets | 54 (84%) |

| Anti-psychotics | 11 (17%) |

| Antidepressants | 23 (36%) |

| Non-opiate analgesics | 59 (92%) |

| Opiate analgesics | 59 (92%) |

| Anti-emetics | 56 (88%) |

| Anti-convulsants | 10 (16%) |

| Anti-parkinsons drugs | 2 (3%) |

| Antibiotics | 48 (75%) |

| Insulin and oral hypoglycaemics | 39 (61%) |

| Thyroxine | 36 (56%) |

| Vitamins and minerals | 41 (64%) |

COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2.

Responses to the question ‘Which of the following groups of patients are you now confident to prescribe to without advice?’

| Group of patients | Confident | Not confident |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | 12 (19%) | 52 (81%) |

| Children | 16 (25%) | 48 (75%) |

| Patients with renal diseases | 17 (27%) | 47 (73%) |

| Patients with liver diseases | 17 (27%) | 47 (73%) |

| Elderly | 37 (58%) | 27 (42%) |

When asked specifically about drug prescribing for patients with hepatic or renal impairment, almost three-quarters of respondents said that their undergraduate teaching on drug metabolism (72%) and drug clearance (75%) had been insufficient to permit them to prescribe with confidence to these groups of patients.

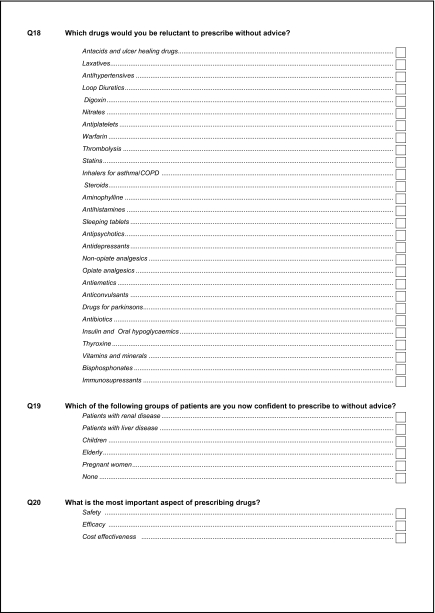

Adverse drug reactions

During the FY1 years, 74% of respondents reported having witnessed an ADR, of whom 14% said the event resulted in hospitalization, 28% prolongation of stay, 20% morbidity and 5% death. Approximately one-third of respondents thought that the ADRs they had witnessed were both predictable (36%) and avoidable (31%). Unfortunately, the majority of witnessed ADRs went unreported, with only 14% of respondents reporting the ADR to the local drug safety committee, and 12% to the UK Yellow Card pharmacovigilance scheme. Almost a third of respondents believed that the ADR they had witnessed would have been prevented with better training (28%) and almost half that they had not been taught enough as an undergraduate (42%) or during the FY1 years (56%) about avoiding ADRs and ensuring patient safety.

Drug–drug interactions

Just over half of respondents (55%) had witnessed a drug–drug interaction during their FY1 years to date, which 31% of respondents said resulted in prolongation of stay, 9% in hospitalization and 11% in morbidity. Sixty percent of respondents believed that they had not had sufficient training at undergraduate level and 73% during their FY1 years about avoiding drug–drug interactions.

Drug prescribing reference sources

Eighty-eight percent of respondents reported that they routinely checked a reference source before prescribing a medication, although 69% did not routinely read the manufacturer's prescribing information supplied with the product. The majority of respondents used the British National Formulary (95%), the ward pharmacist (72%), the local formulary (42%) and other colleagues (63%). The most frequently sought information when consulting a reference source is reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

The information sought by FY1 doctors when using drug reference sources

| Information | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Dose | 60 (94%) |

| Indications | 47 (73%) |

| Contraindications | 54 (84%) |

| Adverse reactions | 47 (73%) |

| Drug–drug interactions | 37 (58%) |

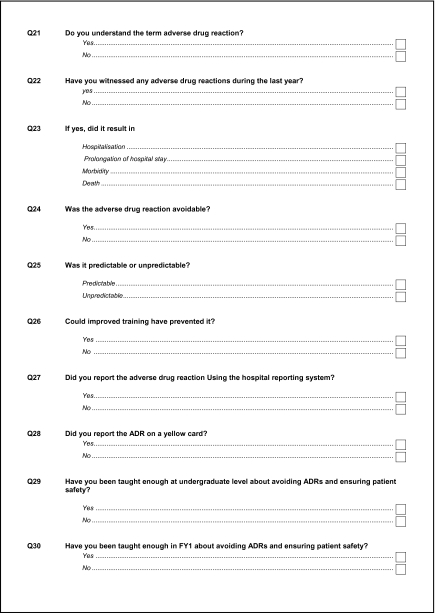

Areas for improving undergraduate and postgraduate teaching in clinical pharmacology and prescribing

At the end of the questionnaire, FY1 doctors were asked, in retrospect, which topics in CPT required more extensive coverage during undergraduate years (Table 4). The topics cited by more than 50% of respondents were: prescribing for special patient groups, drug–drug interactions, ADRs and therapeutic drug monitoring. Topics considered least important were prescription writing (10%) and taking a drug history (8%).

Table 4.

Those areas in which first year foundation doctors agreed more extensive undergraduate education was required

| Aspect of CPT | Number of respondents (%) |

|---|---|

| Basic pharmacology | 35 (55%) |

| Pharmacokinetics | 34 (53%) |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring | 38 (59%) |

| Adverse drug reactions | 33 (52%) |

| Drug–drug interactions | 44 (69%) |

| Medication errors | 14 (22%) |

| Patients with special requirements | 47 (73%) |

| Common conditions | 21 (33%) |

| Common medicines | 29 (45%) |

| Taking a drug history | 5 (8%) |

| Prescription writing | 6 (9%) |

| Drug administration | 24 (38%) |

| Analysing new evidence about drugs | 19 (30%) |

| Obtaining information about drugs | 13 (20%) |

| Risk–benefit analysis | 24 (38%) |

| Doctors responsibilities as a prescriber | 18 (28%) |

Respondents were also asked how undergraduate and postgraduate training could be modified to improve prescribing. In general, respondents thought there should be more practical tutorial-based teaching in clinical pharmacology in the later years of the undergraduate course, using scenarios and real examples. In particular, topics such as commonly used drugs, drug doses, drug–drug interactions and prescribing in special patient groups, such as renal and hepatic disease, were suggested. FY1 doctors also wanted more CPT in their postgraduate teaching programme, highlighting the need to learn from mistakes and examples (specifically ADRs and drug–drug interactions in the hospital where they work), revise undergraduate material in the early part of the year and focus on specific medical conditions.

Discussion

This pilot study asked FY1 doctors, 9 months through their first year of practice, to consider their medicines use and prescribing practice. In particular, they were asked to reflect on how their undergraduate education in CPT had prepared them for their current role as an FY1 doctor.

A significant proportion of FY1 doctors agreed that their undergraduate education had not prepared or equipped them suitably to prescribe safely and rationally, and rated their knowledge of CPT as poor. A large number of respondents also reported ADRs and drug interactions, which had resulted in morbidity and mortality, many of which were believed to be avoidable with training. These findings emphasize the need for improved and focused CPT teaching at both the undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

The majority of FY1 doctors reported that they felt confident in prescribing a variety of medicines unsupervised. However, their chosen medicines tended to reflect ward attachments and routine prescribing workload, rather than low-risk medicines. This was exemplified by the large number of FY1 doctors who felt confident in the unsupervised use of opiates, nonsteroidal analgesics and warfarin, a situation which might be considered inappropriate and which suggests prescribing confidence comes from practice, rather than an appreciation of the true risk and complexities involved.

Only a small number of FY1 doctors were confident in prescribing to special patient groups, including pregnant women and patients with hepatic and renal impairment, even though these patients are not uncommon in hospital. Confident prescribing in these areas was again associated with specialist ward attachment and exposure to special patient groups.

Almost three-quarters of respondents claimed to have witnessed an ADR and half a drug–drug interaction, which had frequently resulted in morbidity or mortality. Over half of respondents agreed that these serious events could have been avoided with better undergraduate and postgraduate training in ADRs and drug interaction avoidance. The doctors who responded to this questionnaire favoured increased undergraduate and postgraduate teaching of a practical nature, relating to day-to-day prescribing/therapeutic issues. Although deficiencies in the basic skills of prescription writing and taking a drug history are responsible for a significant number of drug-related errors [11, 12], the majority of respondents gave focused teaching in these areas a low priority, indicating again that practice, even if inappropriate, breeds complacency rather than correct behaviour.

In this study the majority of respondents were trained in a single medical school. However, there is no reason to believe that the undergraduate and postgraduate training we provide differs substantially from that in other UK medical schools, which follow the recommended curriculum in CPT [6]. Certainly, evidence would suggest that the deficiencies highlighted by this study are widespread throughout the UK [9].

This study provides evidence that FY1 doctors perceive their undergraduate and postgraduate training in prescribing and the safe and rational use of drugs to be deficient, and that as a result patient safety issues have arisen. Junior doctors reported surprisingly high levels of avoidable drug-related morbidity and mortality, which they believed could have been prevented with better training during their undergraduate medical degree, and better consolidation of CPT training during the postgraduate year. These findings add weight to the belief that increased training in medicines use and the potential for patient harm is essential within UK medical schools if we are to ensure high-quality, rational, safe prescribing, and protection of the patient from avoidable morbidity and mortality.

Competing interests: None declared.

Appendix 1

References

- 1.Audit Commission. A Spoonful of Sugar. Medicines Management in NHS Hospitals. London: Audit Commission; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audit Scotland. A Scottish Prescription. Managing the Use of Medicines in Hospitals. Edinburgh: Audit Scotland; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.BBC News. NHS Drug Error ‘Crackdown’ Urged. [2006-September-6]. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4780487.stm.

- 4.Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, Farrar K, Park BK, Breckenridge AM. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.General Medical Council. Tomorrows Doctors: Recommendations on Undergraduate Medical Education. London: GMC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maxwell S, Walley T. Teaching safe and effective prescribing in UK medical schools: a core curriculum for tomorrow's doctors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:496–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronson JK. A prescription for better prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:478–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson JK, Henderson G, Webb DJ, Rawlins MD. A prescription for better prescribing. BMJ. 2006;333:459–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38946.491829.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BBC News. Concerns over Medics Drug Skills. [2006-September-4]. Available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/5192372.stm.

- 10.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: their incidence and clinical significance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:340–4. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandal K, Fraser SG. The incidence of prescribing errors in an eye hospital. BMC Ophthalmol. 2005;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N. Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359:1373–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]