Abstract

What is already known about this subject

Cardiovascular diseases are the major cause of premature death in most Western countries.

Drug treatment, along with diet and lifestyle changes, is the mainstay of prevention and is effective provided that it is maintained over time.

Treatments with antihypertensives or lipid-lowering agents are known to be affected by a high rate of early withdrawal.

What this study adds

Four classes of drugs for cardiovascular prevention were studied, and they showed different patterns of use:

Poor adherence to antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies, probably due to poor perception of risk and a too early start of pharmacological treatment.

Higher adherence to oral hypoglycaemic agents and nitrates, which are used in conditions where disease awareness and the consequences of stopping medication favour compliance.

Aim

To evaluate adherence to chronic cardiovascular drug treatments, in terms of long-term persistence and dose coverage.

Methods

General practice prescription data of antihypertensives, lipid-lowering agents, oral hypoglycaemic agents and nitrates were collected over a 5-year period (1998–2002) in a Northern Italian district (Ravenna, 350 000 inhabitants). We selected subjects (>40 years) receiving at least one prescription of the above drugs in December 1999. For each patient, we documented the regimen at the time of selection and evaluated adherence to treatment during the following 3 years in terms of persistence (at least one prescription per year) and daily coverage (recipients of an amount of medication consistent with daily treatment).

Results

Fewer than 10% of the 32 068 selected subjects were naive to treatment. Antihypertensives were the most represented therapeutic category. Among patients already on treatment in December 1999, persistence was virtually complete, whereas >40% of naive patients withdrew within 1 year, except for nitrates. The rates of coverage were always much lower than the corresponding values of persistence. Coverage was significantly higher in older patients (χ2 for trend 69.41; P < 0.001), males (odds ratio 1.30; 95% confidence interval 1.25, 1.36) and users receiving more than one therapeutic category.

Conclusions

Lack of adherence to chronic cardiovascular treatments represents an important matter of concern: although most people continued treatment over the years, less than 50% received an amount of drugs consistent with daily treatment, thus jeopardizing the proved beneficial effects of available medications.

Keywords: adherence to treatment, antihypertensive agents, hypoglycaemic agents, lipid-lowering agents, nitrates, primary health care

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of premature death in most Western countries. They represent an important source of disability and contribute in large part to the escalating cost of healthcare [1]. More than one-third of the adult Italian population and more than one-half of elderly subjects need pharmacological cardiovascular risk prevention [2] (see also http://www.cuore.iss.it). Although cardiovascular drugs represent almost 50% of all reimbursed prescriptions (among these, 70% are antihypertensive prescriptions) [3], it is well known that hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidaemia are not adequately controlled in a large proportion of cases [2]. In almost all cases, in order to guarantee efficacy (prevention of cardiovascular events or stroke) treatment with cardiovascular drugs should be chronically maintained in patients with hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, angina, diabetes or heart failure.

Despite recommendations, studies in different countries, even in populations at high cardiovascular risk, have found poor adherence to chronic cardiovascular treatments [4–8]. Our group recently reported that the withdrawal rate is exceedingly common in subjects treated with antihypertensive agents (AHAs), particularly during the first year of treatment [9]. This finding prompted us to extend this study by comparing the pattern of use of different drug classes in terms of adherence to therapy, in conditions where risk perception may be different.

The specific aim of this study was to evaluate the pattern of use of the main classes of chronically used cardiovascular drugs in an Italian population, focusing on adherence to treatment. In particular, we considered AHAs, lipid-lowering drugs (LLDs), oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHAs) and nitrates in order to estimate population exposure and to obtain information about adherence by patients, in terms of long-term persistence and dose coverage. Patient- and drug-related elements (e.g. age, gender, drug class, polypharmacy vs. monotherapy) associated with non-adherence were also considered.

Methods

Data collection

Prescription data of cardiovascular drugs were retrieved from the Emilia Romagna Regional Health Authority Database [10], which provides the following information for each reimbursed prescription: identification code of the drug, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code, number of packages and number of defined daily doses (DDD) dispensed [11], code of the patient, date of prescription. The patient code allows retrieval of their drug history without individual identification. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

We collected data of all drugs labelled for the chronic treatment of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia or angina prescribed by general practitioners (GPs) and reimbursed between January 1998 and December 2002 by a Local Health Authority of Emilia Romagna (Ravenna district, with both urban and rural areas, 350 000 inhabitants). The following ATC codes were considered: C02, C03, C07, C08, C09 – drugs labelled for the chronic treatment of hypertension (agents acting on α-adrenergic receptors, diuretics, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers and agents acting on the renin–angiotensin system); A10B – oral antidiabetic drugs; C10 – lipid-lowering agents; and C01DA – nitrates (all but sublingual nitroglycerin).

Cardiac glycosides, low-dose aspirin and insulin preparations were not included in the present analysis because of the limited reliability of data drawn from the National Health Service (NHS) prescription database (see further in Discussion).

Selection of patients

In order to recruit adult patients receiving cardiovascular medications for chronic treatment, we selected subjects aged ≥40 years, permanently living in the area throughout the study period (from 1998 to 2002) and receiving at least one prescription of the drugs listed above in December 1999. For each therapeutic category (AHAs, LLDs, OHAs and nitrates), we identified two groups: (i) patients already on treatment, represented by the subjects receiving at least one prescription of the same therapeutic category during the period January 1998 to November 1999; and (ii) new patients, represented by the subjects having their first prescription in December 1999 (and without any prescription of these drugs during the period January 1998 to November 1999).

Data analysis

For each therapeutic category, prescriptions of each patient were analysed for the 3 years following recruitment (December 1999). Therapeutic regimens were those recorded at recruitment. Adherence to treatment was then evaluated in terms of (i) persistence and (ii) coverage.

Patients were defined as persistent when they received at least one prescription of any agent of the considered therapeutic category in 2000, 2001 and 2002.

Patients were defined as covered when the amount of drugs of the same category received during each of the 3 years of the study was consistent with a daily treatment. To this purpose, we identified the minimal daily dose recommended for maintenance therapy for each drug and calculated the total number of minimal doses of each agent received, by the patient, year by year. Patients reaching at least 300 minimal doses per year were considered as covered, allowing a tolerance of ∼20% over the 365-day period.

Data were analysed by Epi-Info, version 2002 (http://www.cdc.gov/epiinfo/). The relationship between age groups and rate of coverage was analysed by χ2 test for trend. Coverage with different therapeutic regimens was analysed by non-adjusted odds ratio.

Results

In December 1999, 10% (n = 32 068) of the population permanently living in the Ravenna area during the reference period received cardiovascular prescriptions. The cohort had a female:male ratio of 1.3, reflecting the same proportion as in the general population.

Most patients (n = 27 316) received AHAs: among these, 934 were new patients and 26 382 were already on treatment at recruitment; 5264 received LLDs (352 new patients); 2632 received OHAs (142 new patients), and 1948 received nitrates (77 new patients).

Rate of persistence

Patients already on treatment

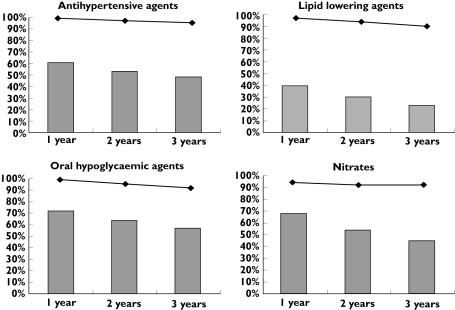

Persistence was virtually complete in the first year of analysis for all therapeutic categories, with a modest decline in the following years, which was minimal for nitrate recipients (2% after 3 years), intermediate for patients receiving AHAs (4% after 3 years) and more pronounced for patients under LLDs or OHAs, but even in these two groups the drop-out rate was <10% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Rates of persistence and coverage of patients already on treatment (diamonds, persistence; bars, coverage)

New patients

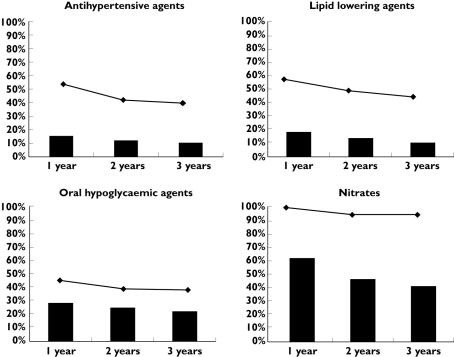

Persistence was very high among nitrate recipients, being complete in the first year and not less than 95% in the following 2 years (Figure 2). This level of persistence was similar to that observed for patients already on treatment. In contrast, in the other three therapeutic categories, marked differences were seen among persistence rates of patients already on treatment vs. new patients. Namely, patients treated with AHAs and LLDs showed a persistence rate of 56 and 59%, respectively, in the first year, decreasing to 42% and 52% in the second year, with no further decrease in the third year. The lowest rate of persistence was observed in patients treated with OHAs.

Figure 2.

Rates of persistence and coverage of new patients (diamonds, persistence; bars, coverage)

Rate of coverage

Patients already on treatment

Rates of coverage in each of the 3 years following recruitment are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. In all categories, percentages of patients covered were much lower than the corresponding values for persistence and the yearly decline was even more pronounced than that observed for persistence. OHA-treated patients started at the relatively higher rate of coverage (72%), which decreased to 57% at 3 years. Patients treated with LLDs showed the lowest rates of coverage (from 40 to 23%).

Table 1.

Odds ratio (OR) for rate of coverage of patients under different therapeutic regimens

| Patients already in treatment | New patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covered patients | Covered patients | |||||||

| Regimen | n | % | OR | (95% CI) | n | % | OR | (95% CI) |

| Antihypertensive agents | ||||||||

| α-Blockers | 539 | 78 | 5.39 | 4.46, 6.52 | 5 | 14 | ND | |

| Combinations of 3 and more classes | 1579 | 65 | 2.8 | 2.55, 3.08 | 2 | 10 | 0.95 | 0, 4.54 |

| Different combinations (two classes) | 1888 | 58 | 2.07 | 1.91, 2.24 | 4 | 10 | ND | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2822 | 57 | 2.03 | 1.89, 2.18 | 26 | 14 | ND | |

| Loop diuretics | 351 | 52 | 1.63 | 1.39, 1.91 | 4 | 7 | ND | |

| Angiotensin II receptor antagonists | 449 | 42 | 1.09 | 0.95, 1.24 | 11 | 18 | 1.88 | 0.84, 4.17 |

| ACE-inhibitors | 3729 | 40 | Ref* | 34 | 10 | Ref* | ||

| Thiazide-like diuretics | 398 | 35 | 0.83 | 0.63, 0.94 | 2 | 3 | ND | |

| β-Blockers | 988 | 35 | 0.81 | 0.74, 0.88 | 9 | 6 | 0.59 | 0.25, 1.32 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | ||||||||

| Combinations | 30 | 60 | 5.1 | 2.79, 9.37 | – | – | – | – |

| Statins | 1036 | 23 | Ref* | 36 | 12 | Ref* | ||

| Fibrates | 109 | 17 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.88 | 1 | 2 | ND | |

| Bile acid sequestrants | 2 | 10 | 0.36 | 0.06, 1.59 | – | – | – | – |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agents | ||||||||

| Biguanides | 286 | 71 | 3.05 | 2.38, 3.92 | 8 | 30 | 3.3 | 0.88, 12.67 |

| Sulphonylureas | 569 | 67 | 2.53 | 2.10, 3.04 | 18 | 29 | ND | |

| Combinations | 554 | 45 | Ref* | 6 | 11 | Ref* | ||

| Nitrates | ||||||||

| Combinations | 68 | 69 | 3.35 | 2.11, 5.32 | 13 | 65 | ND | |

| Isosorbide | 288 | 57 | 2.02 | 1.63, 2.50 | 4 | 40 | 3.96 | 1.16, 13.96 |

| Nitroglycerin | 501 | 40 | Ref* | 15 | 32 | Ref* | ||

Within each therapeutic category, the most frequent regimen or combination therapy were considered as reference treatment.

New patients

In these patients also, the rates of coverage were largely lower than the corresponding values of persistence (Figure 2 and Table 1). This discrepancy was less pronounced for patients treated with OHAs, who showed similarly low rates for both persistence and coverage. For all therapeutic categories, a decline of the rate of coverage was observed during the 3 years of the study. New subjects treated with AHAs, LLDs and OHAs showed a markedly lower rate of coverage than subjects already on treatment (16% vs. 61%, 18% vs. 40% and 29% vs. 72%, respectively, in the first year). In contrast, the rate of coverage for subjects treated with nitrates was almost the same in new vs. patients already on treatment.

Determinants of the rate of coverage

Age and gender

The rate of coverage was significantly higher in older patients among those treated with AHAs (χ2 for trend = 10.48; d.f. = 1; P < 0.05) and those treated with OHAs (11.95; d.f. = 1; P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant age trend was observed in the case of patients under LLDs (χ2 for trend = 1.436; d.f. = 1; P = 0.231) or nitrates (χ2 for trend = 0.154; d.f. = 1; P = 0.695). Females were less covered than males, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.75 for AHAs [confidence interval (CI) 0.72, 0.79], 0.85 for nitrates (CI 0.74, 0. 98) and 0.79 for LLDs (CI 0.71, 0.86). For OHAs this difference was not significant (OR 0.89; CI 0.77, 1.01).

Therapeutic regimens

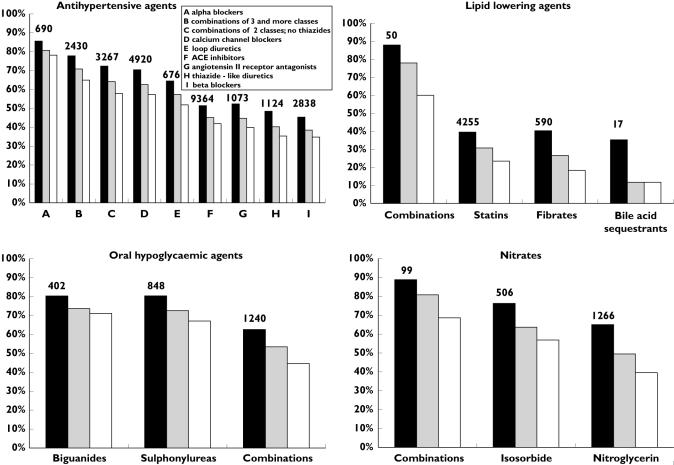

Table 1 shows the statistical analysis of the rate of 3-year coverage by drug class within each therapeutic category. Among patients already on treatment, we observed significant differences within antihypertensive categories. Patients on α-blockers, combinations, calcium channel blockers and loop diuretics showed a significantly higher rate of coverage than those treated with ACE-inhibitors (78–52% vs. 40%), whereas patients treated with thiazide-like diuretics and β-blockers showed a significantly lower rate of coverage (35%). In the category of LLDs, patients treated with combinations were more frequently covered than those who used only statins (60% vs. 23%), whereas patients taking fibrates were very rarely covered (17%). However, combination therapy was prescribed only to a minority of all recipients of LLDs (<1%). Patients on hypoglycaemic monotherapy showed a higher rate of coverage than those treated with combination regimens (67–71% vs. 45%) and, finally, within nitrates, those with nitroglycerin patches showed a lower coverage than those with isosorbide or combinations (40% vs. 57–69%; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rates of coverage of patients already on treatment, by therapeutic regimen among the four therapeutic categories. Coverage is shown for each of the 3 years after the recruitment (black bars, first year; grey bars, second year; white bars, third year). The figures over the bars represent the number of patients at the time of recruitment

Among new patients, the only significant difference in terms of rate of coverage was observed for patients using nitrates: in particular, those taking isosorbide were more frequently covered than subjects receiving nitroglycerin (40% vs. 32%).

When considering together the drugs prescribed for the prevention of global cardiovascular risk (AHAs, LLDs and OHAs), the rate of coverage within each category was higher when patients received additional treatment for other risk factors (see Table 2): the coverage in AHAs increased for any cotreatment (from 45% for single category to 58–67% for cotreatments), the coverage in LLDs was only slightly influenced by the use of other categories, and the coverage in OHAs was mainly influenced by the concurrent use of LLDs (from 62% for OHAs alone to 80% for combinations with LLDs).

Table 2.

Percentage of 3-year coverage among patients already on treatment with specific drugs* from each category, in the presence of combined therapy with other drug categories (single category coverage). The global coverage in the presence of multiple treatments is also reported

| Covered patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Single category coverage | ||||

| Antihypertensive agents | ||||

| Alone | 10 859/23 988 | 45 | Ref | |

| With LLDs | 1211/2086 | 58 | 1.67 | 1.53, 1.83 |

| With OHAs | 677/1103 | 61 | 1.92 | 1.69, 2.18 |

| With LLDs and OHAs | 93/139 | 67 | 2.44 | 1.69, 3.54 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | ||||

| Alone | 603/2946 | 20 | Ref | |

| With AHAs | 520/2086 | 25 | 1.29 | 1.13, 1.48 |

| With OHAs | 20/93 | 22 | 1.06 | 0.62, 1.80 |

| With AHAs and OHAs | 34/139 | 24 | 1.26 | 0.83, 1.90 |

| Oral hypoglycaemic agents | ||||

| Alone | 803/1297 | 62 | Ref | |

| With AHAs | 716/1103 | 65 | 1.14 | 0.96, 1.35 |

| With LLDs | 74/93 | 80 | 2.40 | 1.39, 4.16 |

| With AHAs and LLDs | 99/139 | 71 | 1.52 | 1.02, 2.28 |

| Global coverage | ||||

| AHAs + LLDs | 385/2086 | 18 | Ref | |

| AHAs + OHAs | 549/1103 | 50 | 4.38 | 3.71, 5.16 |

| OHAs + LLDs | 42/93 | 45 | 3.64 | 2.33, 5.67 |

| AHAs + LLDs + OHAs | 20/139 | 14 | 0.74 | 0.44, 1.23 |

Only drug categories aimed at reducing ‘global’ cardiovascular risk are considered. LLDs, Lipid lowering agents; OHAs, oral hypoglycaemic agents; AHAs, antihypertensive agents.

The overall coverage of patients receiving two therapeutic categories ranged from 18% (AHAs plus LLDs) to 50% (AHAs plus OHAs), and was minimal in patients concurrently exposed to the three therapeutic categories (14%).

Discussion

Lack of adherence to chronic cardiovascular treatments is an important matter of concern: although most people continued treatment over the years, <50% received an amount of drugs consistent with daily treatment, thus jeopardizing the proved beneficial effects of available medications.

A critical step in the adherence to cardiovascular treatments is represented by the first few weeks of therapy, when most withdrawals occur [12]. Afterwards, patients actually needing treatment were probably selected and they showed good persistence over time, although with poor coverage. Poor coverage may be ascribed to the use of a very low dosage or, more probably, to intermittent therapy, which means exposure to possible side-effects without proved benefit. Elderly patients had a higher rate of persistence than younger people. Moreover, males were more adherent to therapies than females, probably because men accept medical care only at a more advanced stage of the disease.

A possible bias of this study is the lack of information on diagnosis, which may have led to the inclusion of a few patients receiving cardiovascular drugs for acute conditions. Thus, adherence might have been underestimated. However, a questionnaire-based survey performed in 2002 on a representative sample of the Italian population showed that <1% of patients received drugs of these categories for nonchronic indications [13]. On the other hand, because of the lack of diagnosis, more severe patients requiring daily doses higher than the minimum recommended may have been regarded as falsely adherent. We cannot rule out that the significantly higher adherence observed in older patients was partly due to this. However, we believe that our decision to use the minimal maintenance dose to calculate daily coverage was a reasonable compromise in the light of the potential risk of inflating non-adherence by using a higher reference dose.

Cardiac glycosides, low-dose aspirin and insulin preparations were intentionally excluded from this analysis. Cardiac glycosides have a very low prevalence of use in our population and, most of all, the high variability in the individual dosing regimen makes it hard to evaluate coverage. Concerning low-dose aspirin, in Italy not all preparations of this medicine are reimbursed by the NHS and therefore a prescription database is not an appropriate tool to evaluate adherence. Indeed, some Italian questionnaire-based studies addressing the pattern of use of low-dose aspirin have concluded that prescription of antiplatelets is still far from what is recommended [14, 15]. Insulin prescriptions were also excluded from our analysis, since insulin is often dispensed directly by the Diabetes Centres and those data cannot be easily retrieved.

AHAs represented 85% of cardiovascular treatments for chronic purposes and were characterized by the highest rate of withdrawals: among all patients starting treatment, only 40% still received prescriptions 3 years later and only <10% used these drugs daily.

Considering all patients receiving AHAs, a very high variability among prescribed classes of drugs was seen: as we have already reported [9], polypharmacy was associated with higher adherence to therapy (in terms of coverage, about 60% for major combinations and 35% for β-blockers or minor diuretics in the 3-year period). These findings suggest a possible selection of severe patients for the persistence in therapy.

Non-adherent patients could be divided into two groups. The first includes patients with mild hypertension, probably needing only lifestyle changes, and receiving pharmacological treatment too early. In this case, the risk of adverse effects and a waste of economic resources would represent the main cause of concern. The second group includes patients actually needing antihypertensive treatment, but unaware of the importance of pharmacological control of blood pressure. In these patients, treatment would have poor effectiveness.

A recent study [16] compared awareness of hypertension, prevalence of treatment and outcomes in terms of blood pressure control in some European countries, the USA and Canada. The authors observed in Italy a high awareness of the disease by physicians and a high prevalence of treatment, but poor blood pressure control compared with other countries. This finding seems to confirm that a number of patients are recognized as hypertensive, but not adequately treated. Also, Filippi et al.[17] have identified uncontrolled blood pressure as an important matter of concern in Italy, whether or not patients receive AHAs.

A significant difference existed between patients receiving only AHAs (coverage 46%) and those also treated for other cardiovascular diseases (coverage 61%). This suggests the existence of two subgroups: those with higher cardiovascular risk, treated with multiple pharmacological strategies, who strictly adhere to therapy, and others with lower global risk, who areprescribed only AHAs and are probably less motivated to compliance.

LLDs were associated with the lowest adherence among the categories considered in this study: only 23% of patients exposed to LLDs received an amount of drug consistent with daily treatment. Again, the high gap between persistence and coverage suggests a large proportion of intermittent use.

Some papers published in the last decade have shown very low adherence to LLDs [6, 18, 19]. Comparing our findings with those reported by Larsen et al.[6], the prevalence of LLD use in Italy did not change during the 4-year period 1996–2000 (about 3% of population aged ≥40 years), but persistence was increased from 52% to 88% (data not shown), reaching values observed in 1996 in Denmark and considered by the authors a goal for the Italian population. As claimed by Larsen et al.[20] in a more recent paper, important cardiovascular prevention studies (e.g. 4S, Western Scotland [21]) on the effectiveness of statins on cardiovascular events were viewed with favour by physicians. On the other hand, the marked difference of risk profile between patients in clinical trials and those receiving statins in general practice [22–24] may explain of the lack of adherence in the general population.

Similarly to AHAs, the low adherence to LLDs could be caused by poor perception of risk by the patient as well as by a deviation from the recommended approach to hypolipidaemic therapy. Indeed, lifestyle changes should be the first-line approach when the diagnosis is established. Besides misuse, some authors have identified underuse of statins, in terms of number of patients recruited for lipid-lowering treatment [25]. In Italy, 21% of adult men and 25% of adult women have cholesterol levels >240 mg dl−1[2] (see also http://www.cuore.iss.it). If about 50% of patients with hyperlipidaemia need to be treated, then the prevalence of treatment of 3% found in Italy seems to be very low.

The large variability in prevalence of the treated population is probably explained also by the variability in the level of cardiovascular risk profile related to different lifestyles. Accordingly, Italy and Spain showed the lowest use of LLDs. Concerning adherence to drug therapy, our results are similar to those reported in other countries [23, 25–27]. Perreault et al.[25], who found decreased persistence after 3 years (39%) in Canada, have claimed that ‘barriers to persistence occur early in the therapeutic course’ and this statement appears appropriate also in our case.

In contrast to other chronic cardiovascular diseases, immediate invalidating symptoms typical of angina can determine a greater perception of risk. As a consequence, it is not unexpected that nitrates represented the only therapeutic category with virtually complete persistence both for subjects already on treatment and for new patients, with only a slight difference in terms of coverage (>40% after a 3-year follow-up). In any case, also for nitrates a large proportion of patients did not use these drugs continuously, but, unlike other chronic cardiovascular therapeutic categories, this pattern should not be considered as inappropriate. Nitrates usually represent an add-on therapy in antianginal regimens based on oral β-blockers or calcium channel blockers [28]. Accordingly, we observed that 73% of patients were also receiving basal oral treatment for angina.

The highest percentage of coverage was observed for prevalent patients receiving OHAs. This fits well with the evidence that non-adherence represents an immediate threat to diabetes control. On the other hand, the results among incident patients showed very poor coverage, with a value of persistence corresponding to the lowest among cardiovascular therapies, representing an important matter of concern. The need for continuous treatment to reach good metabolic control and optimal treatment in terms of drugs and daily dosages may help to interpret our results: (i) more than half of patients starting OHAs withdrew, probably either switching to insulin or actually stopping treatment; (ii) the low difference between persistence and coverage could indicate a good use of drugs among patients who were assigned to OHAs at the end of the course of stabilization.

Only about 15% of all new patients who continued treatment were not covered. Current guidelines indicate that the first approach to treatment in Type 2 diabetes should be based on diet, exercise and lifestyle changes. Only in subjects who do not attain good metabolic control should oral hypoglycaemic agents be used. The low rate of persistence may be explained by inappropriate use of OHAs at the very beginning of disease, a treatment that needs to be stopped if patients achieve reasonable weight loss. In the long term, patients diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes may also need exogenous insulin, when metabolic control is no longer attained with oral treatment. Insulin prescription was not included in our analysis because insulin is dispensed directly by hospitals and data on its use cannot be retrieved. This limit could represent a bias for the estimation of persistence, but not for the gap between persistence and coverage.

Conclusions

Among subjects receiving chronic cardiovascular treatment, poor adherence to therapy is an important matter for concern, especially for AHAs and LLDs. In both cases, poor awareness of the importance of pharmacological control of cardiovascular risk factors or a premature start of pharmacological treatment could represent reasons for poor adherence. This hypothesis is supported by the higher adherence to treatments, such as those for angina and diabetes, for which the harmful effects that follow the discontinuation of therapy result in higher awareness of the importance of drug treatment.

In conclusion, considering (i) the higher adherence found in more severe patients (i.e. receiving complex regimens and medications for more than one chronic purpose) and (ii) the lack of achievement of therapeutic goals (e.g. in terms of blood pressure values or cholesterol concentrations) reported in the literature, we hypothesize the existence of three different groups of patients receiving chronic prescription of cardiovascular medications: (i) seriously ill patients, showing virtually complete adherence; (ii) patients actually needing chronic medications, but not adherent to treatment; (iii) subjects with a mild medical condition, who probably need only lifestyle changes, but are nonetheless given medications – these subjects may be less adherent because of unshared goals between patient and physician. To optimize resource allocation, major educational efforts should be addressed towards the second subgroup. The recent proposal of the metabolic syndrome [29] as a condition to identify subjects at higher risk who need multiple pharmacological treatments may help to check for persistence and coverage in more severe patients. Further studies including also clinical data (e.g. diagnosis, hospital admissions, blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose levels) are needed, in order to identify the determinants of low adherence to chronic cardiovascular treatment.

Acknowledgments

Competing interests: None declared. We wish to thank the Local Health Authority of Ravenna for supplying prescribing data. The study was supported by grants from the Regione Emilia Romagna and the University of Bologna.

References

- 1.De Backer G, Ambrosioni E, Borch-Johnsen K, Brotons C, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, Ebrahim S, Faergeman O, Graham I, Mancia G, Cats VM, Orth-Gomer K, Perk J, Pyorala K, Rodicio JL, Sans S, Sansoy V, Sechtem U, Silber S, Thomsen T, Wood D. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease and prevention in clinical practice. Atherosclerosis. 2003;171:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vanuzzo D, Pilotto L, Uguccioni M, Pede S, Valagussa F, Gaggioli A, Palmieri L, Dima F, Lo NC, Seccareccia F, Giampaoli S. [Cardiovascular epidemiology: trends of risk factors in Italy] Ital Heart J. 2004;5(Suppl. 8):19S–27S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AAVV. L'Uso dei Farmaci in Italia – Rapporto Nazionale Anno 2004. Osservatorio Nazionale Sull'Impiego dei Medicinali. Rome: Ministero della Salute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo JA, Simons WR. Variations in compliance among hypertensive patients by drug class: implications for health care costs. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1446–57. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caro JJ, Salas M, Speckman JL, Raggio G, Jackson JD. Persistence with treatment for hypertension in actual practice. CMAJ. 1999;160:31–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen J, Vaccheri A, Andersen M, Montanaro N, Bergman U. Lack of adherence to lipid-lowering drug treatment. A comparison of utilization patterns in defined populations in Funen, Denmark and Bologna, Italy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:463–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trilling JS, Froom J. The urgent need to improve hypertension care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:794–801. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones JK, Gorkin L, Lian JF, Staffa JA, Fletcher AP. Discontinuation of and changes in treatment after start of new courses of antihypertensive drugs: a study of a United Kingdom population. BMJ. 1995;311:293–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poluzzi E, Strahinja P, Vargiu A, Chiabrando G, Silvani MC, Motola D, Sangiorgi CG, Vaccheri A, De Ponti F, Montanaro N. Initial treatment of hypertension and adherence to therapy in general practice in Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:603–9. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0957-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montanaro N, Vaccheri A, Magrini N, Battilana M. FARMAGUIDA: a databank for the analysis of the Italian drug market and drug utilization in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;42:395–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00280125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (Norway) ATC Index with DDDs. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugtenburg JG, Blom AT, Kisoensingh SU. Initial phase of chronic medication use; patients' reasons for discontinuation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:352–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motola D, Vaccheri A, Silvani MC, Poluzzi E, Bottoni A, De Ponti F, Montanaro N. Pattern of NSAID use in the Italian general population: a questionnaire-based survey. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:731–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monesi L, Avanzini F, Barlera S, Caimi V, Lauri D, Longoni P, Roccatagliata D, Tombesi M, Tognoni G, Roncaglioni MC. Appropriate use of antiplatelets: is prescription in daily practice influenced by the global cardiovascular risk? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:595–601. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0948-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manes C, Giacci L, Sciartilli A, D'Alleva A, De Caterina R. Aspirin overprescription in primary cardiovascular prevention. Thromb Res. 2006;118:471–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H, Banegas JR, Giampaoli S, Joffres MR, Poulter N, Primatesta P, Stegmayr B, Thamm M. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United States. Hypertension. 2004;43:10–17. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103630.72812.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filippi A, Bignamini AA, Sessa E, Samani F, Mazzaglia G. Secondary prevention of stroke in Italy: a cross-sectional survey in family practice. Stroke. 2003;34:1010–4. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000062888.90293.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraha I, Montedori A, Stracci F, Rossi M, Romagnoli C. Statin compliance in the Umbrian population. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:659–61. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0675-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Martino M, Degli EL, Ruffo P, Bustacchini S, Catte A, Sturani A, Degli EE. Underuse of lipidlowering drugs and factors associated with poor adherence: a real practice analysis in Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:225–30. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0911-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen J, Andersen M, Kragstrup J, Gram LF. High persistence of statin use in a Danish population: compliance study 1993–1998. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;53:375–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teeling M, Bennett K, Feely J. The influence of guidelines on the use of statins: analysis of prescribing trends 1998–2002. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:227–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walley T, FolinoGallo P, Stephens P, Van Ganse E. Trends in prescribing and utilization of statins and other lipid lowering drugs across Europe 1997–2003. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:543–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrade SE, Walker AM, Gottlieb LK, Hollenberg NK, Testa MA, Saperia GM, Platt R. Discontinuation of antihyperlipidemic drugs – do rates reported in clinical trials reflect rates in primary care settings? N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1125–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perreault S, Blais L, Dragomir A, Bouchard MH, Lalonde L, Laurier C, Collin J. Persistence and determinants of statin therapy among middleaged patients free of cardiovascular disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61:667–74. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0980-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J. Longterm persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288:455–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, Bohn RL, Monane M, Mogun H, LeLorier J. Persistence of use of lipidlowering medications: a crossnational study. JAMA. 1998;279:1458–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crea F, Galvani M, Canonico A, Cirrincione V, Di Pasquale G, Mauri F, Penco M, Zardini P, Vassanelli C, Barsotti A, Mazzotta G. [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of unstable angina. Update 2000] Ital Heart J Suppl. 2000;1:1597–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]