Abstract

Aims

To investigate the tolerability, safety and pharmacokinetics of S-3304 in healthy volunteers treated with high doses of S-3304 for 28 days.

Methods

Thirty-two healthy volunteers were recruited. Four male and four female subjects were allocated to one of four doses (800 mg, 1600 mg, 2400 mg and 3200 mg). At each dose six volunteers took active medication and two volunteers took placebo in a double-blind fashion. Volunteers took a single dose on days 1 and 28 for pharmacokinetic purposes, and took twice daily doses from day 3–27. The pharmacokinetics of S-3304 and its hydroxy metabolites were evaluated. Tolerance was based on subjective adverse events, clinical examination, vital signs, ECG and laboratory tests including haematology and biochemistry profiles using CTC grading.

Results

Doses up to 2400 mg twice daily were generally well tolerated. At 3200 mg twice daily, five volunteers including one randomized to placebo were withdrawn from treatment mainly due to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation. Cmax of S-3304 on day 1, whose geometric mean and 95% confidence interval were 66.3 µg ml−1 (48.8, 90.0) for 800 mg, 82.6 µg ml−1 (69.3, 98.6) for 1600 mg, 89.5 µg ml−1 (79.5, 100.7) for 2400 mg, and 110.5 µg ml−1 (88.9, 137.7) for 3200 mg, respectively, was correlated with the log-transformed peak ALT (P < 0.0001 for male and P = 0.048 for female volunteers).

Conclusions

In healthy volunteers the maximum tolerated dose of S-3304 was 2400 mg twice daily. ALT elevation was the most frequent dose-limiting factor and was correlated with Cmax on day 1.

Keywords: ALT, matrix metalloproteinase, pharmacokinetics, phase I, S-3304, safety

Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-endopeptidases responsible for degradation of the extracellular matrices, including collagen and proteoglycan, and are believed to play important roles in embryogenesis, tissue remodeling and diseases processes [1]. In the 1990s it was postulated that MMP inhibition would provide a new class of therapeutic agents for a variety of disease indications [2–4]. Now, it is known that there are at least 20 isoforms of MMPs [5]. They are classifiedbased on their substrate specificity and structural characteristics. As the extracellular matrix structures are remodeled and maintained via well-regulated expressions and involvement of MMPs of different substrate specificities, it has been considered an important issue to identify which inhibition profiles should be pursued for potential therapeutic applications.

MMP-2 and 9 are more abundantly expressed than other MMP isoforms in cancer patients with certain tumour types, such as nonsmall cell lung cancer [6, 7], breast cancer [8, 9], bladder cancer [10, 11] and prostate carcinoma [12]. They are thought to play critical roles in angiogenesis particularly in the breakdown of vascular basement membranes [13] and are believed relevant to tumour malignancy, such as tumour invasion and metastasis [14]. Potent specific MMP inhibitors might work as anticancer agents by correcting the imbalance observed in pathological states [15]. Abnormal regulation of MMP-2 and 9 are not only reported for cancer patients but also in other diseases, such as heart failure [16].

A number of MMP inhibitors have entered clinical development, but none has been licensed. Disappointing results were reported for phase III studies in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer stage IIIB/IV [17, 18], metastatic breast cancer [19], and advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma [20]. However, it is still thought that MMP inhibitors may have therapeutic potential for earlier stage cancer patients or for specific cancer patient populations, given that they may be most effective in prevention of metastasis. Bramhall et al. [21] and King et al. [22] published promising results of marimastat for the treatment of patients with inoperable gastric cancer and for adjuvant treatment in patients with colorectal cancer, respectively. Marimastat caused musculoskeletal adverse effects as a dose limiting toxicity [23]. One possible solution for the successful development of MMP inhibitors is to diminish the musculoskeletal side-effects that are associated with marimastat [24]. Whilst controversial, it has been hypothesized that broad inhibition of MMPs including MMP-1 by marimastat impairs the homeostatic control of type I collagen at joint tissues, resulting in musculoskeletal disorders [25].

S-3304, Nα-[[2-[5-[[4-methylphenyl]ethynyl]thienyl]]sulphonyl]-d-tryptophan, is an orally active MMP-2 and -9 inhibitor, which was developed as a potential noncytotoxic cancer agent [26]. Through its lack of inhibition of MMP-1 it is hoped it will avoid musculoskeletal adverse effects. After demonstrating excellent safety profiles in nonclinical studies, S-3304 entered into a clinical development programme in 1998.

First-in-man studies were conducted in healthy male subjects. Excellent tolerability and linear pharmacokinetic profiles were demonstrated within a dose range up to 800 mg twice a day for up to 14 days [27]. As no pharmacokinetic saturation was observed in the dose range up to 800 mg twice daily and no dose-limiting toxicities could be identified, another healthy volunteer study was recommended to determine a maximum tolerated dose and investigate the pharmacokinetics at higher doses in healthy male and female volunteers, before patient studies were started. In addition, it was decided to prolong the treatment period to 28 days in healthy volunteers to identify any dose limiting toxicities.

Methods

Materials

S-3304 was manufactured and formulated as 200 mg capsules by Shionogi & Co. Ltd, in accordance with good manufacturing practice. Placebo capsules were formulated by Shionogi & Co. Ltd.

Volunteer enrolment

Thirty-two healthy male and female volunteers were recruited in a single centre, and were allocated to four dose levels comprising 800 mg twice daily, 1600 mg twice daily, 2400 mg twice daily and 3200 mg twice daily. Eight volunteers per dose level, four male and four female volunteers, were randomized so that six took active medication and two placebo in a double-blind manner. Randomization was not based on gender because it was not planned to study gender difference. Volunteers were screened before study entry and gave informed written consent before enrolment. The protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the local research ethics committee.

Study treatment

Two hundred mg gelatin capsules were used for dosing. Four to 16 pills, depending on the dose, were taken over a 2 min period. Volunteers took a single oral dose after breakfast on day 1, received no treatment on day 2, and took twice daily doses, 12 h apart, after breakfast and dinner between days 3 and 27 (inclusive). Volunteers were not dosed on day 2 because pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for 48 h after the initial single dose on day 1. Finally they took a single dose after breakfast on day 28. Treatment of the next dose level group was started, based on interim safety reports generated by the principal investigator after the first 2-week treatment period. Each volunteer received treatment at only one dose level.

Safety assessment

Safety was evaluated based on adverse events reported by volunteers, clinical laboratory tests (including haematology and biochemistry profiles), electrocardiography (ECG) and vital signs. An adverse event was defined as any undesirable event occurring to a subject during the clinical study whether or not related to S-3304 or placebo. If three or more of eight subjects either experienced a dose limiting toxicity, which was defined as greater than grade 2 toxicity according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, had increased concentrations of liver enzymes to greater than two times the upper limit of the reference range, or were withdrawn from further dosing due to symptoms interfering with normal daily activities at the investigators' discretion, the treatment was discontinued and the next lower dose level was considered as the maximum tolerated dose.

Pharmacokinetics

Blood samples were collected at the following time points: predose and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36 and 48 h post morning dose on days 1 and 28, where the blood drawing at 48 h post dose on day 1 occurred immediately before the morning dose of day 3. On day 14, blood samples were taken at predose and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13, 14, 16, 20 and 24 h post morning dose. The blood drawing at 12 and 24 h post dose took place immediately before the evening dose on day 14 and the morning dose on day 15, respectively. Serial blood samples were drawn on days 1, 14 and 28, as scheduled, for the 800 mg twice daily, 1600 mg twice daily and 2400 mg twice daily dose groups, but were done only on days 1 and 14 for the 3200 mg twice daily dose group, as treatment was discontinued on day 15 because most of the volunteers were withdrawn from the study. Trough plasma samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were taken prior to morning and evening doses on days 11–14 and 25–28. All bioanaytical procedures were validated prior to sample analyses. Plasma concentrations of S-3304 and its hydroxy metabolites, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304, were determined, according to the previously reported method using high performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry detection (LC-MS/MS) with some modifications [27], where the lower limits of quantification (LLQ) of S-3304 and its hydroxyl metabolites were 0.1 µg ml−1 and 0.001 µg ml−1, respectively, and the correlation coefficients were >0.990 for all the accepted batches of all analytes. Between day variability of S-3304, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 quality control (QC) samples was 2.0–9.0%, 2.6–8.4% and 3.0–8.3%, respectively, and within day variability of S-3304, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 QC samples was 1.2–8.8%, 1.6–12.2% and 1.4–14.4%, respectively. To evaluate single dose pharmacokinetics, individual concentration-time data on day 1 were used to derive pharmacokinetic parameters by non-compartmental analysis. All the pharmacokinetic parameters were computed using the WinNonlin (version 3.0, Pharsight) software. The maximum concentration (Cmax) and time of maximum concentration (tmax) were the observed values obtained from the concentration data. The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for all the analytes was calculated for zero to 12 h, which is presented as AUC0–12 h, for zero to a last measurable time, which is represented by AUC0–last, and for zero to infinity, which is presented as AUC0–∞, using the linear trapezoidal method. AUC0–∞ was calculated by AUC0–last+ Clast/λz, where Clast was determined as plasma concentration at a last measurable time point and λz was determined as slope of the linear regression line for log concentration vs. time. Estimates of the apparent terminal half-life (t1/2) were calculated from (ln2)/λz. Similarly, to assess steady-state pharmacokinetics, the parameters Cmax,ss, tmax,ss, t1/2,ss, and AUC0–12 h,ss were evaluated from the individual concentration-time data on day 28 for 800 mg twice daily, 1600 mg twice daily and 2400 mg twice daily, or on day 14 for 3200 mg twice daily. Protein binding of S-3304 was also determined after equilibrium dialysis of 3 and 8 h post morning dose serum samples that were obtained on days 1, 14 and 28, as described previously [27]. Volume shift was considered [28]. The metabolite ratio is defined as the ratio of AUC0–12 h of metabolites to that of the parent compound.

Statistical analysis

Dose proportionality was assessed for Cmax, and AUC0–12 h, using analysis of variance and linear regression techniques using SAS version 8 [29]. The following linear regression model was fitted: log[Parameter] = μ + β × log[Dose]. This formula is referred to as a power model because after exponentiation: [Parameter] = α × [Dose]β where the estimate of β is a measure of dose proportionality and α = eμ. The criterion for dose proportionality was that β = 1 (if β = 0 this implies dose-independent parameters) based on the 95% confidence interval for β. To estimate correlation between ALT and Cmax, peak ALT concentrations were log-transformed and subjected to analysis of variance and linear regression with Cmax on day 1.

Results

Study population

A total of 32 healthy volunteers were enrolled into this study. Their demography is shown in Table 1. Four male and four female volunteers were enrolled at each dose level. Randomization was performed within the dose level but not within the same sex. As a consequence, 14 male volunteers were allocated to active medications with four to 800 mg twice daily, three to 1600 mg twice daily, three to 2400 mg twice daily and four to 3200 mg twice daily. Hence, both median body weight and height appear smaller in the placebo group than in the S-3304 groups.

Table 1.

Demography of subjects enrolled to the study

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 8) | 800 mg (n = 6) | 1600 mg (n = 6) | 2400 mg (n = 6) | 3200 mg (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.5 (22–30) | 23.5 (20–29) | 26.0 (20–34) | 23.0 (20–25) | 23.0 (21–32) |

| Height (m) | 1.635 (1.60–1.88) | 1.785 (1.57–1.83) | 1.735 (1.60–1.85) | 1.730 (1.65–1.83) | 1.765 (1.56–1.83) |

| Weight (kg) | 63.45 (54.8–81.4) | 72.20 (50.5–89.8) | 71.20 (51.1–79.9) | 67.90 (59.9–85.9) | 80.15 (57.3–86.9) |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 23.0 (20–27) | 22.5 (20–27) | 23.0 (20–26) | 22.5 (21–27) | 24.5 (24–28) |

Data are expressed in median (minimum–maximum). Four male and four female subjects were enrolled to each dose level. Randomization to active treatment and placebo was carried out per dose level but not within subjects of the same sex.

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma concentrations of S-3304, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 were determined and plotted against time for the initial dosing (day 1) and the last dosing (day 28), as shown in Figure 1. Marked differences were not observed in the time courses between days 1 and 28. Metabolite concentrations were approximately 1% and 0.1% that of S-3304 for 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304, respectively.

Figure 1.

Plasma concentrations of S-3304 (•), 5-hydroxy-S-3304 (▪) and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 (▴) after oral administration of S-3304 capsules at 800 mg twice daily, 1600 mg twice daily, 2400 mg twice daily and 3200 mg twice daily. Serial blood sampling was performed on days 1 and 28 except for the 3200 mg twice daily dose, for which treatment was discontinued on day 15 because of safety concerns. Mean values are plotted with SD

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for single dose administrations on day 1 and day 28, as shown in Tables 2 and 3, except for the 3200 mg twice daily dose. At the 3200 mg twice daily dose, the steady state pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for day 14, because most of the subjects had been discontinued from treatment for safety concerns. As for S-3304 on day 1, mean Cmax and AUC0–∞ increased dose dependently from 68.6 µg ml−1 and 359 µg ml−1 h at 800 mg to 112 µg ml−1 and 819 µg ml−1 h at 3200 mg, respectively. At steady state, mean Cmax,ss and AUC0–∞,ss of S-3304 increased dose dependently from 79.9 µg ml−1 and 411 µg ml−1 h at 800 mg to 140 µg ml−1 and 943 µg ml−1 h at 3200 mg, respectively. These parameter increases were not dose-proportionate. Similar saturable pharmacokinetic profiles were observed for the S-3304 metabolites, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of S-3304 and its metabolites following a single oral administration on day 1

| Dose | 800 mg (n = 6) | 1600 mg (n = 6) | 2400 mg (n = 6) | 3200 mg (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h (μg ml−1 h) | 310 ± 110 | 369 ± 74 | 439 ± 57 | 641 ± 134 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg ml−1 h) | 359 ± 130 | 430 ± 88 | 520 ± 75 | 819 ± 246 |

| Cmax (μg ml−1) | 68.6 ± 19.2 | 83.6 ± 14.2 | 90.0 ± 10.0 | 112 ± 21 |

| tmax (h) | 3.5 (2–5) | 2.5 (2–5) | 5 (3–5) | 5 (5–5) |

| t1/2 (h) | 11.8 ± 0.8 | 10.6 ± 1.1 | 12.3 ± 3.0 | 10.8 ± 1.3 |

| 5-hydroxy-S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h (μg ml−1 h) | 1.75 ± 0.72 | 3.40 ± 1.70 | 5.52 ± 2.32 | 5.10 ± 1.69 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg ml−1 h) | 2.26 ± 1.02 | 4.30 ± 1.33 | 7.01 ± 2.77 | 7.51 ± 3.65 |

| Cmax (μg ml−1) | 0.376 ± 0.115 | 0.642 ± 0.193 | 1.06 ± 0.36 | 0.893 ± 0.314 |

| tmax (h) | 5.5 (3–8) | 5 (4–5) | 5.5 (4–8) | 6.5 (5–8) |

| t1/2 (h) | 11.8 ± 1.3 | 10.9 ± 1.4 | 12.4 ± 2.8 | 9.6 ± 2.3 |

| Metabolite ratio | 0.0058 ± 0.0021 | 0.0092 ± 0.0025 | 0.0125 ± 0.0049 | 0.0080 ± 0.0023 |

| 6-hydroxy-S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h (μg ml−1 h) | 0.30 ± 0.14 | 0.46 ± 0.21 | 0.72 ± 0.40 | 0.58 ± 0.15 |

| AUC0–∞ (μg ml−1 h) | 0.457 ± 0.208 | 0.734 ± 0.317 | 1.10 ± 0.52 | 1.01 ± 0.32 |

| Cmax (μg ml−1) | 0.0527 ± 0.0215 | 0.0815 ± 0.0526 | 0.130 ± 0.068 | 0.0978 ± 0.0317 |

| tmax (h) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (4–8) | 5.5 (4–8) | 5 (5–6) |

| t1/2 (h) | 10.5 ± 2.5 | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 12.2 ± 1.7 | 10.4 ± 2.1 |

| Metabolite ratio | 0.0010 ± 0.0003 | 0.0013 ± 0.0005 | 0.0016 ± 0.0009 | 0.0009 ± 0.0003 |

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined under fed conditions. Metabolite ratio is defined as the ratio of AUC0–12 h of the metabolite to that of S-3304. Data are presented as mean ± SD, except for tmax, which is presented as median (minimum–maximum).

Table 3.

Steady state pharmacokinetic parameters of S-3304 and its metabolites following 14 day or 28 day twice daily multiple oral administrations

| Dose | 800 mg*(n = 6) | 1600 mg*(n = 4) | 2400 mg*(n = 5) | 3200 mg†(n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h,ss (μg ml−1h) | 411 ± 117 | 466 ± 80 | 634 ± 170 | 943 ± 317 |

| Cmax,ss (μg ml−1) | 79.9 ± 19.6 | 92.7 ± 12.7 | 120 ± 21 | 140 ± 27 |

| tmax,ss (h) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) |

| t1/2,ss (h) | 14.2 ± 1.2‡ | 14.8 ± 3.4 | 15.9 ± 1.8§ | ND |

| AUC0–12 h,ss:AUC0–12 h | 1.40 ± 0.32 | 1.34 ± 0.17 | 1.45 ± 0.34 | 1.48 ± 0.20 |

| 5-hydroxy-S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h,ss (μg ml−1 h) | 3.06 ± 1.49 | 5.14 ± 2.83 | 8.27 ± 3.62 | 8.81 ± 6.14 |

| Cmax,ss (μg ml−1) | 0.511 ± 0.183 | 0.939 ± 0.515 | 1.57 ± 0.67 | 1.26 ± 0.88 |

| tmax,ss (h) | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–5) | 4 (0–6) | 5 (3–6) |

| t1/2,ss (h) | 20.7 ± 6.7 | 13.9 ± 1.0 | 17.3 ± 3.5 | ND |

| AUC0–12 h,ss:AUC0–12 h | 1.74 ± 0.43 | 1.53 ± 0.26 | 1.79 ± 0.80 | 1.66 ± 0.35 |

| Metabolite ratio | 0.0072 ± 0.0023 | 0.0105 ± 0.0043 | 0.0133 ± 0.0062 | 0.0092 ± 0.0045 |

| 6-hydroxy-S-3304 | ||||

| AUC0–12 h,ss (μg ml−1 h) | 0.486 ± 0.245 | 0.899 ± 0.558 | 1.24 ± 0.63 | 1.07 ± 0.74 |

| Cmax,ss (μg ml−1) | 0.0838 ± 0.0358 | 0.162 ± 0.117 | 0.215 ± 0.117 | 0.146 ± 0.100 |

| tmax,ss (h) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) |

| t1/2,ss (h) | 20.6 ± 6.5 | 16.0 ± 2.4 | 18.9 ± 4.3§ | ND |

| AUC0–12 h,ss:AUC0–12 h | 1.66 ± 0.53 | 1.79 ± 0.70 | 2.69 ± 2.42 | 2.33 ± 1.11 |

| Metabolite ratio | 0.0011 ± 0.0004 | 0.0018 ± 0.0009 | 0.0020 ± 0.0010 | 0.0011 ± 0.0004 |

Steady state pharmacokinetic parameters based on day 28 plasma concentrations.

Steady state pharmacokinetic parameters based on day 14 plasma concentrations.

n = 5.

n = 4.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined under fed conditions. For assessments of steady state pharmacokinetics, volunteers were subject to serial blood drawing after breakfast on day 28, except for 3200 mg BID dose level, for which all the subjects were withdrawn from the treatment but steady state pharmacokinetic data were derived from the plasma concentrations on day 14. The observed degree of accumulation is represented by AUC0–12h,ss/AUC0–12h, where is AUC0–12h on day 1. Metabolite ratio is defined as the ratio of AUC0‐12h of the metabolite to that of S-3304. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, except for tmax, which is presented as median (minimum–maximum).

In order to analyze the dose dependency and dose proportionality, power models were fitted to Cmax and AUC0–12 h for S-3304 and metabolites. The analysis was performed for day 1, day 14 and, if applicable, day 28. Since similar results were obtained on days 14 and 28, only the data for day 14 are shown in Figure 2. Dose dependency and proportionality were assessed with the confidence intervals of the exponent of the function: y = α × xβ, where x and y represent dose and parameter, respectively. Exponential intercepts (95% confidence intervals) of log-transformed power functions and exponents (95% confidence intervals) were: 4.05 (0.85, 19.2) and 0.418 (0.209, 0.628) for Cmax of S-3304; 15.99 (1.80, 142.10) and 0.469 (0.175, 0.764) for AUC0–12 h of S-3304; 0.00218 (0.00004, 0.13414) and 0.801 (0.245, 1.356) for Cmax of 5-hydroxy-S-3304; 0.00979 (0.00016, 0.60861) and 0.843 (0.286, 1.400) for AUC0–12 h of 5-hydroxy-S-3304; 0.00118 (0.00001, 0.11623) and 0.623 (0.004, 1.243) for Cmax of 6-hydroxy-S-3304; 0.00827 (0.00009, 0.75077) and 0.616 (0.008, 1.224) for AUC0–12 h of 6-hydroxy-S-3304, respectively. These results indicate that Cmax and AUC of S-3304 and its hydroxyl metabolites are dose dependent but less than dose proportionate. For 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304, the exponents were significantly different from 0 and dose dependence was confirmed. Any point estimate was considerably less than 1 and therefore the dose dependent increase appeared less than proportionate. In addition, similar power model fittings were carried out for Cmax and AUC0–12 h on day 1 and day 28 and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Dose-relationships in Cmax and AUC0–12 h on day 14. Plotted are Cmax and AUC0–12 h of S-3304 (top panels), 5-hydroxy-S-3304 (middle panels) and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 (bottom panels) from individual subjects vs. dose. 5-OH-S-3304 and 6-OH-S-3304 represent 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304, respectively. Solid lines represent power model functions, y = α × xβ, which were derived from linear regression of log-transformed parameters. Similar correlations were obtained for day 1 and day 28 (data not shown) and only the correlations for day 14 are provided as representative data

Median tmax, mean t1/2, and AUC0–12 h,ss:AUC0–12 h were obviously dose-independent as shown in Tables 2 and 3. There were no marked differences in the dose dependence of those pharmacokinetic parameters between S-3304, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304, except for the AUC0–12 h,ss:AUC0–12 h of 6-hydroxy-S-3304, which appears to have increased as the dose increased up to 2400 mg twice daily.

Metabolite ratios of 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 were determined as shown in Table 3. The mean metabolite ratios of 5-hydroxy-S-3304 ranged from 0.0072 to 0.0133. The mean metabolite ratios of 6-hydroxy-S-3304 were generally smaller than those of 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and ranged from 0.0011 to 0.0020.

Figure 3 (left) shows mean trough concentrations of S-3304 (A), 5-hydroxy-S-3304 (B) and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 (C) for 800 mg twice daily, 1600 mg twice daily, 2400 mg twice daily and 3200 mg twice daily. In general, the morning trough concentrations were approximately 2–4 fold higher than those of the evening troughs within a dose range from 800 mg twice daily to 3200 mg twice daily, regardless of S-3304 or its hydroxyl metabolites. These results were consistent with the previous finding for the dose range of 200 mg−800 mg twice daily [27]. Since the morning trough concentrations were higher than the evening trough concentrations, it was interesting to study the time courses of plasma concentrations after the evening dose. As shown in Figure 3 (right), plasma concentrations of S-3304, 5-hydroxy-S-3304 and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 were determined both after morning and evening doses on day 14. Time to peak concentration was longer after the evening dose than after the morning dose. However, no marked difference was observed for Cmax and AUC0–12 h between post morning and evening dose periods on day 14 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Trough concentrations (left) and time course on day 14 (right) of plasma S-3304 (top), 5-hydroxy-S-3304 (middle) and 6-hydroxy-S-3304 (bottom) concentrations were plotted for 800 mg twice daily (•), 1600 mg twice daily (▪), 2400 mg twice daily (▴) and 3200 mg (○), respectively. The concentration-time data on day 14 are shown separately from those of day 1 and day 28 here, because the purpose of the data presentation was to compare the concentration-time data between post morning and post evening doses. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Morning and evening doses were administered at time 0 and 12 h, respectively

Protein binding was determined on days 1, 14 and 28 at 3 and 8 h after morning doses. The mean protein binding was just under 100% regardless of the dose, time and serum concentrations of S-3304.

Adverse events

A total of 114 treatment-emergent adverse events were reported by 23 volunteers (96%) randomized to S-3304, whereas 44 adverse events were reported by seven volunteers (88%) who were randomized to placebo. As shown in Table 4, the most frequently reported adverse events were headache, abdominal pain, nausea, sore throat, liver function test abnormalities, nasal congestion and alopecia. Headache was reported by 10 of 24 volunteers randomized to S-3304 active medication but was also reported by three of eight volunteers randomized to placebo, indicating headache was not specific to study drug treatment. Nausea was reported by 37.5% and 17% of volunteers who were randomized to S-3304 active medication and placebo, respectively. Nasal congestion and alopecia were reported more frequently by volunteers randomized to placebo than those randomized to S-3304. More volunteers who were randomized to S-3304 had sore throats, liver function test abnormalities, urinary frequency and back pain than those who were randomized to placebo.

Table 4.

Most commonly observed treatment emergent adverse events

| 800 mg (n = 6) | 1600 mg (n = 6) | 2400 mg (n = 6) | 3200 mg (n = 6) | Placebo (n = 8) | Total (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 13 (2) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 0 | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 2 | 11 (2) |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Sore throat | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Liver function tests abnormal* | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 (2) | 0 | 5 (2) |

| Nasal congestion | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Alopecia | 1 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 | 5 (1) |

| Dizziness (postural) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Urinary frequency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Dizziness (excluding vertigo) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Lethargy | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Back pain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Constipation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

Liver enzymes were considered elevated if the peak concentration during the study period was greater than twice of the upper limit of normal ranges.

Tabulated are treatment emergent adverse events reported by more than two subjects per dose level and total. Provided are the numbers of subjects who reported adverse events. All adverse events were reported as mild except for the ones given in the parentheses, which were of moderate severity.

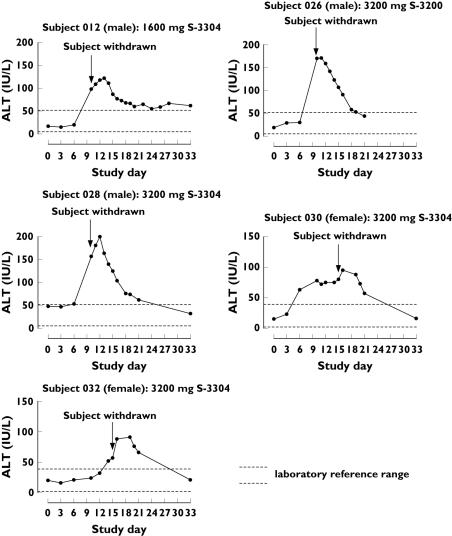

Elevated liver function tests (transaminases) were the most common cause for subject treatment discontinuation (see Table 5), accounting for 37.5% of the subjects who were withdrawn from the study. In this study, exceeding two times the upper limit of reference ranges for liver enzymes was considered the criteria for clinical significance. A total of five subjects had abnormal serum transaminase concentrations during the study treatment. Time courses of plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) changes of the individual subjects are shown in Figures 5 and 6. One volunteer at the 1600 mg twice daily dose was withdrawn from treatment on day 10 due to ALT elevation of grade 1, at the investigator's discretion. His peak measured ALT and AST were 122 IU l−1 on day 13 and 65 IU l−1 on day 12, respectively. No liver function test abnormality was observed with 2400 mg twice daily but abnormalities were observed in four volunteers at the 3200 mg twice daily dose, all of whom were randomized to S-3304. Two of the four volunteers experienced ALT elevation of grade 2 and were discontinued from the treatment on day 10. Their peak ALT concentrations were 171 IU l−1 on day 11 and 200 IU l−1 on day 12. Their peak AST concentrations were 103 IU l−1 on day 10 and 92 IU l−1 on day 12, respectively. The other two volunteers had peak ALT concentrations of 95 IU l−1 on day 16 and of 91 IU l−1 on day 17 and peak AST concnetrations of 61 IU l−1 on day 16 and of 53 IU l−1 on day 16, respectively. All these elevations of ALT and AST were reversible and returned to within the reference ranges 2–3 weeks after the concentrations peaked.

Table 5.

Summary of discontinuation due to adverse events

| Subject | Dose | Day last dosed | Reasons for withdrawal | Severity* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1600 mg | 10 | Abnormal liver function tests | Grade 1 |

| B | 1600 mg | 20 | Increased creatine phosphokinase | Grade 3† |

| C | 2400 mg | 26 | Alopecia | Grade 2 |

| D | 3200 mg | 10 | Abnormal liver function tests | Grade 2 Grade 1 |

| Blood in stools | Grade 1 | |||

| E | 3200 mg | 13 | Abdominal pain | Grade 2 |

| Vision blurred | Grade 2 | |||

| F | 3200 mg | 10 | Abnormal liver function tests | Grade 2 |

| G | 3200 mg | 15 | Headache | Grade 2 |

| H | Placebo | 15 | Headache | Grade 2 |

Severity of adverse events is based on NCI Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0.

Please note the event was not symptomatic but classified into grade 3 according to the NCI CTC.

Figure 5.

Time courses of plasma ALT concentrations of individual subjects who discontinued study treatment. Plasma samples were drawn on unscheduled days as well as per protocol after the abnormality emerged. All subjects were withdrawn from the study treatment on the days indicated with arrows. Dotted horizontal lines represent the normal range of ALT in the institution

Figure 6.

Time courses of plasma AST concentrations of individual subjects who discontinued study treatment. Plasma samples were drawn on unscheduled days as well as per protocol after the abnormality became to emerge. All subjects were withdrawn from the study treatment on the days indicated with arrows. Dotted horizontal lines represent normal range of AST in the institution

ALT and AST were the only clinical laboratory parameters that were changed during the treatments of this study in a clinically meaningful manner. ALT changed more markedly than AST. Thus, the correlation between ALT and Cmax was studied. Furthermore, particularly Cmax on day 1 was chosen for the study, because Cmax on day 1 would become available earlier and, therefore, be more useful to predict potential risks of ALT elevation than Cmax on later treatment days. To determine any correlation between ALT and a pharmacokinetic parameter, log-transformed peak ALT concentrations were subjected to linear regression analyses vs. Cmax on day 1. In this analysis, male and female data were processed separately because of their different reference ranges, which were 5–52 IU l−1 for males and 2–39 IU l−1 for females, respectively. Although greater than 2.5 times upper limit of normal range is classified as grade 2 or more severity in the NCI CTC, two times the upper limit of normal ranges were used for indication of withdrawal of the subject from the study to ensure subjects' safety. Plasma ALT concentrations were log-transformed and subjected to linear regression analysis with Cmax on day 1. Correlation coefficients of Cmax on day 1 and log-transformed ALT were 0.8567 and 0.6361 for males and females, respectively. Slopes of the regression lines between Cmax and log-transformed ALT (95% confidence interval, P value) were estimated as 0.0301 (0.0187, 0.0415, P < 0.0001) and 0.0208 (0.0002, 0.0413, P = 0.0480) for males and females, respectively. Log-transformed peak ALT concentrations were plotted against Cmax on day 1, as shown in Figure 4. The geometric mean values and 95% confidence intervals of Cmax on day 1 were 66.3 µg ml−1 (48.8, 90.0) for 800 mg, 82.6 µg ml−1 (69.3, 98.6) for 1600 mg, 89.5 µg ml−1 (79.5, 100.7) for 2400 mg, and 110.5 µg ml−1 (88.9, 137.7) for 3200 mg, respectively. Correlations between ALT and AUC were also studied and similar results were obtained (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Relationship between S-3304 Cmax on day 1 and peak plasma ALT. Peak plasma ALT during the period between administration and discharge are plotted vs. Cmax of S-3304 on day 1. The solid lines represent the exponential functions of Cmax that were derived from the regression analysis. Dotted straight lines represent two times upper limit of normal ranges, which are 104 IU l−1 and 78 IU l−1 for male and female subjects, respectively, which were used as one of the criteria for subject withdrawal. Correlation coefficients of Cmax on day 1 and log-transformed ALT were 0.8567 (P < 0.0001) and 0.6361 (P = 0.0480) for males and females, respectively

In addition, one female volunteer randomized to 1600 mg twice daily was found to have an abnormally high, clinically relevant increase in plasma creatine phosphokinase (CPK). The subject's CPK concentrations were 2405 IU l−1 on day 21, which was markedly increased from 81 IU l−1 on the previous measurement day (day 17). The reference range was 25–319 IU l−1 and she was withdrawn from the treatment on the same day. The subject's plasma CPK concentration increased up to 3140 IU l−1 and returned to 255 IU l−1, within the normal range, by day 25. The subject's CPK MB fraction was measured at the same time and was found to be within the normal range (data not shown). The CPK increase was not associated with myalgia or muscle tenderness. The subject reported headache, paresthesia in the tongue and lips, stiff neck, and constipation, but they were all of grade 1. No exercise was reported by the subject, in association with the CPK increase.

Table 5 summarizes volunteer discontinuations. Except for the one volunteer who experienced the elevated CPK, the volunteers were discontinued due to grade 1 or 2 adverse events. The frequent adverse events leading to discontinuation included abnormal liver function tests (transaminases). One of the subjects with a moderate severity headache, who was withdrawn, was randomized to placebo. Four of the seven volunteers withdrawn were randomized to 3200 mg twice daily. Two volunteers were withdrawn due to multiple adverse events, including abnormal liver function tests, blood in stools, abdominal pain and blurred vision.

Discussion

In the present study, female volunteers were treated with S-3304 for the first time. Although four female and four male volunteers were enrolled to each dose level, randomization occurred regardless of the sex and, as a consequence, more female volunteers were randomized to placebo.

Doses of S-3304 from 200 mg to 800 mg twice daily had been investigated for the treatment duration up to 14 days prior to this study. The previous study revealed that Cmax and AUC were dose proportionate with doses up to 800 mg twice daily [27]. Dose limiting toxicity had not been identified. The present study demonstrated that systemic exposure increased at doses above 800 mg, but less than dose proportionality, and that the maximum tolerated dose could be identified in a healthy volunteer population.

The dose-dependent but less than proportionate increases in Cmax and AUC were observed both on day 1 and at steady state. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, there was no dose dependence in t1/2. Thus, the less than dose proportionate nature of Cmax and AUC could not be explained by any elimination process but could rather be explained simply by a saturable absorption process. The previous study demonstrated a clear dose linearity of pharmacokinetics within a dose range up to 800 mg twice daily, in contrast to the present study where the pharmacokineitcs were studied within a dose range from 800 mg twice daily to 3200 mg twice daily. These results suggest that S-3304 absorption would become saturable when the dose exceeds 800 mg. Tables 2 and 3 also show that AUC0–12 h,ss at steady state was greater than AUC0–12 h on day 1 but almost comparable with AUC0–∞ on day 1. These results demonstrated that steady state was achieved during treatment with S-3304 up to 28 days.

An apparent difference between morning and evening trough concentrations of S-3304 was observed, as shown in Figure 3. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus have been reported to have higher trough concentrations in the morning than in the evening [30]. It is thought that the difference between morning and evening trough concentrations of cyclosporin and tacrolimus is caused by delayed absorption of these drugs after the evening dose. Our speculation is that a similar mechanism could underlie the circadian variation of plasma S-3304 concentrations, which was demonstrated by the delay in tmax after the evening dose.

As determined in this study, the serum protein binding rate of S-3304 is extremely high. Whilst only the unbound fraction contributes to the biological function, a number of highly protein bound drugs are effective, e.g. paclitaxel. In a separate clinical study in patients with solid tumours, S-3304 was demonstrated to inhibit local MMP activity at the tumour site after 28 days of treatment [31].

The present study determined the concentrations of 5-hydroxy and 6-hydroxy-S-3304. In the previous study [27], it was demonstrated that, as opposed to the in vitro digestion with human liver microsomes [32], 5-hydroxy-S-3304 is produced more than the 6-hydroxy isoform in human plasma in vivo. It is not clear why this discrepancy was observed but, since both metabolites are biologically active, we recommend that both these metabolites, as well as S-3304, should be measured in phase II clinical studies.

One of the objectives of the present study was to determine a maximum tolerated dose in healthy volunteers. Unlike cytotoxic anticancer drugs for cancer patients, milder toxicity criteria were set for the definition of maximum tolerated dose for healthy volunteers. As shown in Table 5, there were eight subjects who discontinued the treatment, including one on placebo, two on 1600 mg twice daily, one on 2400 mg twice daily and four on 3200 mg twice daily treatments. All were withdrawn due to grade 1 and/or grade 2 toxicity, except for one volunteer who had a plasma CPK elevation of grade 3, which is discussed below. However, one subject who received placebo was withdrawn from the treatment. As shown in Table 4, several subjects who received placebo reported adverse events that were commonly reported by those who received S-3304. The adverse events seen during placebo treatment were likely influenced by genuine adverse drug reactions in those around them, and contain an element of the ‘halo effect’. In the present study, none of the six subjects randomized to 800 mg twice daily discontinued treatment, unlike the previous clinical study [27]. From this study it was concluded that oral administration of S-3304 of up to and including 2400 mg twice daily was subjectively well tolerated by the healthy volunteers and that the maximum tolerated dose for healthy volunteers was estimated at 2400 mg twice daily.

One subject was withdrawn from treatment because of a CPK elevation of grade 3. The subject did not perform physical exercise before the abrupt CPK increase. No musculoskeletal symptoms were associated with this event. It should be noted that the subject's CPK MB fraction over this period did not reach a clinically significant level. Similar unexplained substantial CPK increases were documented in clinical reports of the antipsychotic benzisoxazole derivative risperidone [33], chloroquine treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus [34], and the fusion inhibitor enfuvirtide for HIV patients [35]. In future studies, the effects of S-3304 upon CPK concentrations should also be investigated to collect relevant information and to identify any potential risk of S-3304 treatment.

All six volunteers randomized to 3200 mg twice daily treatment had increased plasma ALT concentrations, which were classified into grade 1 or 2 according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI CTC) ver 2. Plasma ALT concentrations under twice the upper limit of reference range are usually not considered as clinically significant, and were not reported as adverse events for two volunteers at the 3200 mg twice daily dose level. Elevated ALT may be considered as a dose-limiting factor of S-3304 based on the previous nonclinical toxicology studies reported [36] and the present data. No histological abnormality was detected in pathological specimens in the nonclinical toxicology studies. In the present study, Cmax on day 1 was correlated with the ALT and AST elevations. If the drug is clinically effective, it may be of value to determine Cmax following the first dose to identify patients predisposed to raised transaminases. Further investigations will be required to validate this hypothesis in the future.

In conclusion, the present study has demonstrated that S-3304, a novel matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor designed to inhibit selectively MMP-2 and MMP−9, is generally well tolerated by healthy male and female volunteers at doses up to and including 2400 mg twice daily for 28 days. Pharmacokinetic analysis indicated dose–responsiveness was still observed but linearity was no longer demonstrated within a dose range over 800 mg twice daily. Cmax on day 1 may be an appropriate pharmacokinetic parameter to predict peak plasma ALT concentrations during treatment with S-3304, which should help identify patients at risk of drug-induced liver enzyme abnormalities. The present data support a clinical trial in cancer patients with a dose range higher than 800 mg twice daily.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the professional medical advice of Drs Gene Resnick and Herbert Swarz, for the helpful discussions with Drs Mitsuaki Ohtani, Takayuki Yoshioka, Ryuji Maekawa, Takashi Hayashi and Yasunori Uragari, and for the technical assistance of Ms Val Brockwell.

References

- 1.Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991;5:2145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Docherty AJ, O'Connell J, Crabbe T, Angal S, Murphy G. The matrix metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors: prospects for treating degenerative tissue diseases. Trends Biotechnol. 1992;10:200–7. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(92)90214-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon JL, Drummond AH, Galloway WA. Metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapeutics. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993;11:S91–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wojtowicz-praga SM, Dickson RB, Hawkins MJ. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Invest New Drugs. 1997;15:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1005722729132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagase H, Woessner JF., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21491–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iizawa T, Fujisawa T, Suzuki M, Motohashi S, Yasufuku K, Yasukawa T, Baba M, Shiba M. Elevated levels of circulating plasma matrix metalloproteinase 9 in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:149–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown PD, Bloxidge RE, Stuart NSA, Gatter KC, Carmichael J. Association between expression of activated 72-kilodalton gelatinase and tumor spread in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:574–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zucker S, Lysik RM, Zarrabi MH, Moll U. Mr 92,000 type IV collagenase is increased in plasma of patients with colon and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:140–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Djonov V, Cresto N, Aebersold DM, Burri PH, Altermatt HJ, Hristic M, Berclaz G, Ziemiecki A, Andres AC. Tumor cell specific expression of MMP-2 correlates with tumor vascularisation in breast cancer. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerhards S, Jung K, Koenig F, Daniltchenko D, Hauptmann S, Schnorr D, Loening SA. Excretion of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in urine is associated with a high stage and grade of bladder carcinoma. Urology. 2001;57:675–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nordqvist AC, Smurawa H, Mathiesen T. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in meningiomas associated with different degrees of brain invasiveness and edema. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:839–44. doi: 10.3171/jns.2001.95.5.0839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanoh Y, Akahoshi T, Ohara T, Ohtani N, Mashiko T, Ohtani S, Egawa S, Baba S. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and prostate-specific antigen in localized and metastatic prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:1813–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matrisian LM. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in matrix remodelling. Trends Genet. 1993;6:121–5. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(90)90126-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDougall, Matrisian LM. Contribution of tumor and stromal matrix metalloproteinases to tumor progression, invasion and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1995;141:351–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00690603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li BH, Zhao P, Liu SH, Yu YM, Han M, Wen JK. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 in colorectal carcinoma invasion and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;28:3046–50. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altieri P, Brunelli C, Garbaldi S, Nicolino A, Spallarossa P, Olivotti L, Rossettin P, Barsotti A, Ghigliotti G. Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 are increased in plasma of patients with heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33:648–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leighl NB, Paz-ares L, Douillard JY, Peschel C, Arnold A, Depierre A, Santoro A, Betticher DC, Gatzemeier U, Jassem J, Crawford J, Tu D, Bezjak A, Humphrey JS, Voi M, Galbraith S, Hann K, Seymour L, Shepherd FA. Randomized phase III study of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BMS-275291 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. National Cancer Institute of Canada-Clinical Trials Group Study BR 18. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2831–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bissett D, O'Byrne KJ, von Pawel J, Gatzemeier U, Price A, Nicolson M, Ercier R, Mazabel E, Penning C, Zhang MH, Collier MA, Shepherd FA. Phase III study of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor prinomastat in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:842–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparano JA, Bernardo P, Stephenson P, Gradishar WJ, Ingle JN, Zucker S, Davidson NE. Randomized phase III trial of marimastat versus placebo in patients with metastatic breast cancer who have responding or stable disease after first-line chemotherapy: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial E2196. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4683–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore MJ, Hamm J, Dancey J, Eisenberg PD, Dagenais M, Fields A, Hagan K, Greenberg B, Colwell B, Zee B, Tu D, Ottaway J, Humphrey R, Seymour L. Comparison of gemcitabine versus the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor BAY 12–9566 in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3296–302. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bramhall SR, Hallissey MT, Whiting J, Scholefield J, Tierney G, Stuart RC, Hawkins RE, McCulloch P, Maughan T, Brown PD, Baillet M, Fielding JW. Marimastat as maintenance therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1864–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King J, Zhao J, Clingan P, Morris D. Randomised double blind placebo control study of adjuvant treatment with the metalloproteinase inhibitor, marimastat, in patients with inoperable colorectal hepatic metastases: significant survival advantage in patients with musculoskeletal side-effects. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:639–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepherd FA, Giaccone G, Seymour L, Debruyne C, Bezjak A, Hirsh V, Smylie M, Rubin S, Martins H, Lamont A, Krzakowski M, Sadura A, Zee B. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of marimastat after response to first-line chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. a trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada-Clinical Trials Group and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4434–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown PD. Ongoing trials with matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors. Expert Opin Invest Drug. 2000;9:2167–77. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.9.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalinsky DR, Shetty B, Pithavala Y, Bender S, Neri A, Webber S, Appelt K, Collier M. Prinomastat, a potent and selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor – preclinical and clinical development for oncology. In: Clendeninn NJ, Appelt K, editors. Cancer Drug Discovery and Development: Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 2000. pp. 143–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura Y, Watanabe F, Nakatani T, Yasui K, Fuji M, Komurasaki T, Tsuzuki H, Maekawa R, Yoshioka T, Kawada K, Sugita K, Ohtani M. Highly selective and orally active inhibitors of type IV collagenase (MMP-9 and MMP-2): N-sulfonylamino acid derivatives. J Med Chem. 1998;41:640–9. doi: 10.1021/jm9707582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Marle S, van Vliet A, Sollie F, Kambayashi Y, Yamada-Sawada T. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of oral S-3304, a novel matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor, in single and multiple dose escalation studies in healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;43:282–93. doi: 10.5414/cpp43282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima JJ, Mackichan JJ, Libertin N, Sabino J. Influence of volume shifts on drug binding during equilibrium dialysis: correction and attenuation. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1983;11:483–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01062207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gough K, Hutchinson M, Keene O, Byrom B, Ellis S, Lacey L, McKellar J. Assessment of dose proportionality: report from the statisticians in the pharmaceutical industry/pharmacokinetics UK Joint Working Party. Drug Inform J. 1995;29:1039–48. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iwahori T, Takeuchi H, Matsuno N, Johjima Y, Konno O, Nakamura Y, Hama K, Uchiyama M, Ashizawa T, Okuyama K, Nagao T, Abudoshukur M, Hirano T, Oka K. Pharmacokinetic differences between morning and evening administration of cyclosporine and tacrolimus therapy. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1739–40. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creaven PJ, Sullivan DM, Gail-Eckhardt S, Bukowski R, Bonomi P, Rao S, Ikeda M, Kambayashi Y, Yamada-Sawada T, Ohtani M. A phase I study of S-3304 a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in patients with solid tumors. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:S77. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi M, Nezasa K, Kawahara S, Inazawa K, Baba T, Sakamoto K, Koike M, Yoshikawa T. Non-clinical assessments of drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics of S-3304, a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:S72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holtmann M, Meyer AE, Pitzer M, Schmidt MN. Risperidone-induced marked elevation of serum creatine kinase in adolescence. A case report. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36:317–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-45121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richter JG, Becker A, Ostendorf B, Specker C, Stoll G, Neuen-Jacob E, Schneider M. Differential diagnosis of high serum creatine kinase levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:319–23. doi: 10.1007/s00296-003-0309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fung HB, Guo Y. Enfuvirtide: a fusion inhibitor for the treatment of HIV infection. Clin Ther. 2004;26:352–78. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kato I, Yoshida T, Muranaka R, Kondo K, Miyake Y, Hirose H, Sameshima H, Izumi H. Non-clinical assessments of safety profiles of S-3304, a novel matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:S76. [Google Scholar]