Abstract

The pathogenesis of bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) infections is complex and only partly understood. It remains controversial whether interferon is produced in cells infected with cytopathic(cp) BVDVs which do not persist in vivo. We show here that a cpBVDV (NADL strain) does not induce interferon responses in cell culture and blocks induction of interferon-stimulated genes by a super-infecting paramyxovirus. cpBVDV infection causes a marked loss of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3), a cellular transcription factor that controls interferon synthesis. This is attributed to expression of Npro, but not its protease activity. Npro interacts with IRF-3, prior to its activation by virus-induced phosphorylation, resulting in polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of IRF-3. Thermal inactivation of the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme prevents Npro-induced IRF-3 loss. These data suggest that inhibition of interferon production is a shared feature of both ncp and cpBVDVs and provide new insights regarding IRF-3 regulation in pestivirus pathogenesis.

Keywords: interferon regulatory factor-3, innate immunity, pestivirus, bovine viral diarrhea virus, N-terminal protease, ubiquitination, retinoic acid inducible gene I, Toll-like receptor 3, interferon-stimulated gene, sendai virus

Introduction

Mammalian cells respond to viral infections by rapid induction of type I interferons (IFN-α and β) and subsequent up-regulation of hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), which establish an antiviral state in host cells and prevent viral replication (Goutagny, Severa, and Fitzgerald, 2006; Sen, 2001). Viral nucleic acids within viral genome or expressed during infection present major pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that are recognized by membrane-bound Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and/or the caspase recruitment domain (CARD)-containing, retinoic acid inducible gene I (RIG)-like cytoplasmic RNA helicases. These PAMP receptors subsequently recruit different adaptor molecules, relaying signals to downstream kinases that activate a number of transcription factors, among which IFN regulatory factors (IRFs), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and ATF/C-Jun coordinately regulate IFN-β transcription. IRF-3 is a constitutively expressed, latent transcription factor that plays a central role in this type I IFN response. It is activated through the TLR3-Toll–interleukin 1 receptor domain–containing adaptor inducing IFN-β (TRIF) pathway, or the RIG-I/melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) pathways via the adaptor, mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS, also known as IPS-1, VISA, or Cardif), following specific phosphorylation of a cluster of serine/threonine residues close to its C-terminus by two non-canonical IκB kinases, Tank-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) or IKKε. Phosphorylated IRF-3 then dimerizes and translocates into the nucleus where it associates with the transcription coactivators, CREB binding protein (CBP)/p300, to stimulate IFN-β transcription (Akira, Uematsu, and Takeuchi, 2006; Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Kawai and Akira, 2006; Kawai and Akira, 2006; Kawai et al., 2005; Servant, Grandvaux, and Hiscott, 2002; Seth et al., 2005; Sharma et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2002; Yoneyama et al., 2004). During co-evolution with their hosts, many viruses have acquired mechanisms that specifically perturb the signaling mechanisms leading to IRF-3 activation. A prime example is the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which utilizes its serine protease to cleave critical adaptor molecules, MAVS and TRIF, thus disrupting virus-induced IRF-3 activation (Foy et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2006; Loo et al., 2006; Meylan et al., 2005).

To maintain cellular homeostasis and prevent tissue damage due to excessive IFN responses, cells have also evolved mechanisms to switch off IFN induction (Goutagny, Severa, and Fitzgerald, 2006). While these pathways are not yet as well studied, the abundance of IRF-3 appears to be regulated in part by proteasome-dependent degradation following virus infections, although there are both cell type- and virus-specific differences in how this occurs (Collins, Noyce, and Mossman, 2004; Lin et al., 1998). Recently, it was reported that dsRNA or viral infection induces the phosphorylation at Ser339 of IRF-3, in addition to the well-recognized C-terminal phospho-acceptor sites, resulting in the recruitment of the peptidylprolyl isomerase, Pin1, through a Ser339-Pro340 motif, and subsequent polyubiquitination and degradation of IRF-3 via a proteasome-dependent pathway (Saitoh et al., 2006). The E3 ligases responsible for polyubiquitination of phosphorylated IRF-3 are currently not known, however, the SKP1-Cullin1-Fbox protein (SCF) complex, which consists of multi-subunit RING-type E3 ligases, may participate in IRF-3 degradation following Sendai virus (SeV) infection (Bibeau-Poirier et al., 2006). Importantly, the NSP1 protein of rotavirus has been recently shown to interact with IRF-3 and to target it for proteasome-dependent degradation, suggesting that viruses can potentially exploit these cellular regulatory pathways to subvert innate host defenses (Barro and Patton, 2005).

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV), along with classical swine fever virus (CSFV) of pigs and border disease virus (BDV) of sheep, represent a group of important veterinary viruses that comprise the genus Pestivirus within the family Flaviviridae. Like the closely related Hepacivirus in this family, pestiviruses are small enveloped viruses that have a positive sense, single-stranded RNA genome. The ~12 kB pestivirus genome encodes a single polyprotein that is translated via an internal ribosome entry site-dependent mechanism, and that is subsequently processed into 11–12 structural and nonstructural (NS) proteins (Rice, 1996). Unique to the pestiviral polyprotein is the presence of a small, 20-kDa protein at its N-terminus, the N-terminal protease (Npro). Npro is a papain-like cysteine protease and its only well-characterized function is to direct its C-terminal cis-cleavage from the nascent polyprotein, thereby generating the mature N-terminus of the nucleocapsid protein (Rumenapf et al., 1998). Npro has no homologs among members of other genera in the family Flaviviridae, and has been shown to be dispensable for the replication of BVDV and CSFV in vitro. However, for reasons that remain poorly understood, Npro deletion mutants have impaired viral growth kinetics (Gil et al., 2006; Lai et al., 2000; Ruggli et al., 2003; Tratschin et al., 1998).

As an economically important cattle pathogen, BVDV causes significant respiratory and reproductive disease. It exists as two biotypes: cytopathic (cp) and non-cytopathic (ncp), depending on the presence of cytopathic effect in cultured cells. cpBVDVs are derived from ncp viruses by mutations or genomic recombination and differ from ncpBVDVs in temporal downregulation of NS2-3 autoprocessing. While efficient NS2-3 cleavage is observed in cells infected with both biotypes of BVDVs early after infection, NS2-3 autoprocessing is barely detectable at later stages of infection with ncpBVDVs in contrast to being only moderately decreased with cpBVDVs. (Lackner et al., 2004; Meyers and Thiel, 1996). Both cp and ncpBVDVs can cause acute infections, but only ncpBVDV is able to establish life-long persistent infection following intra-uterine infection during the first trimester of pregnancy (Brock, 2003; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003). While the life-long persistence of ncpBVDV likely reflects immunotolerance, the mechanisms underlying the differences in the in vivo phenotypes of cpBVDV and ncpBVDV remain obscure. Both acute and persistent BVDV infections were reported to render host animals more susceptible to a variety of secondary virus infections (Fulton et al., 2000; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003; Potgieter, 1997), indicating that BVDV infection may disrupt innate or adaptive host immune responses.

Previous work has shown that BVDV can modulate IFN induction in host cells. While it remains controversial regarding whether cpBVDVs trigger IFN production, it is well established that infection with ncpBVDVs does not induce type I IFNs in vitro (Brackenbury, Carr, and Charleston, 2003; Charleston et al., 2001; Gil et al., 2006; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003; Schweizer et al., 2006). Furthermore, ncpBVDV infection has been shown to block the induction of IFN synthesis by dsRNA or a super-infecting virus, Semliki Forest virus (Baigent et al., 2002; Schweizer and Peterhans, 2001). These observations suggest that ncpBVDVs may encode one or more proteins that disrupt IFN signaling pathways. Unlike the closely related hepacivirus and hepacivirus-like GBV-B, the NS3/4A protease of BVDV does not inhibit viral activation of the IFN-β promoter (Chen et al., 2007; Horscroft et al., 2005). Instead, accumulating evidence has suggested a role for Npro as an IFN antagonist (Gil et al., 2006; Horscroft et al., 2005; La Rocca et al., 2005; Ruggli et al., 2005).Using a reverse genetics approach, Gil et al (Gil et al., 2006) recently reported that mutations close to the N-terminus of Npro modulate the ability of BVDV to trigger IFN induction, suggesting that the N-terminal domain of BVDV Npro may be important for IFN antagonism (Gil et al., 2006). Similarly, an Npro-deletion mutant CSFV lost the ability to block poly(I-C)-induced IFN production and induced IFN synthesis spontaneously in cell culture (Ruggli et al., 2003). Two recent reports suggested that the Npro of CSFV down-regulates IRF-3 at the promoter level (La Rocca et al., 2005) or posttranscriptionally by inducing its proteasomal degradation (Bauhofer et al., 2007). Here, we show that infection of cells with a cpBVDV strain, NADL, not only fails to trigger an IFN response, but also actively blocks the expression of ISGs normally triggered by infection with an unrelated paramyxovirus. The Npro of BVDV NADL, when expressed alone or in the context of BVDV infection, specifically targets IRF-3 for polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation through a PIN1-independent mechanism, significantly reducing the available IRF-3 abundance and resulting in disruption of cellular IFN responses.

Results

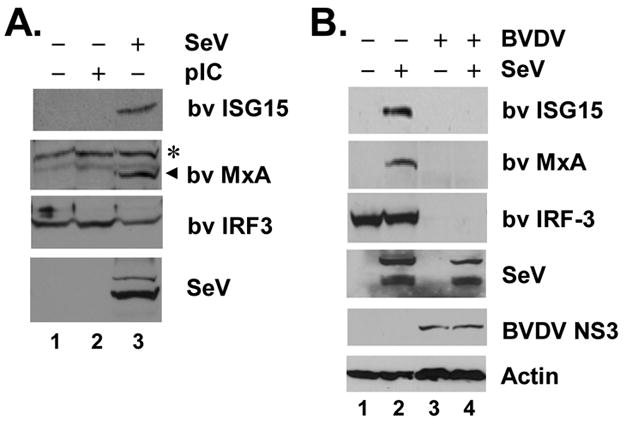

Virus-induced IFN response is abrogated in cpBVDV infected cells

Although infection with ncpBVDVs blocks IFN induction in cultured cells, previous studies have provided contradictory results concerning the ability of cpBVDV infection to trigger IFN synthesis. In an effort to clarify these earlier results, we determined the effect of infection with a cpBVDV strain, NADL, on induction of MxA and ISG15, two well-characterized ISGs, in bovine kidney MDBK cells. Initial experiments assessed whether MDBK cells respond to the presence of extracellular poly(I-C) or infection with Sendai virus (SeV), a paramyxovirus that is unrelated to BVDV, well-characterized inducers of type I IFN synthesis through the TLR3 and RIG-I pathways, respectively (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Yoneyama et al., 2004). MDBK cells do not appear to possess an active TLR3 pathway, as even large amounts of extracellular poly (I-C) induced neither ISG15 nor MxA synthesis (Fig. 1A). In contrast, infection of MDBK cells with SeV led to the expression of readily detectable bovine ISG15 and MxA proteins, indicating the presence of a functional RIG-I pathway in these cells (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, this response was lost in MDBK cells infected with BVDV NADL (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 4), which also did not induce the expression of bovine ISG15 and MxA (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 3 vs 1). The lack of ISG induction in BVDV-infected cells was not due to interference with replication of the super-infecting SeV, as similar levels of SeV proteins were expressed, regardless of BVDV infection status (SeV panel, compare lanes 4 vs. 2). Thus, like ncpBVDV (Baigent et al., 2002; Schweizer and Peterhans, 2001), infection of MDBK cells with the cytopathic NADL strain of BVDV disrupts virus-induction of the IFN response.

Fig. 1.

Virus-induced IFN response is abrogated in cpBVDV infected cells. A. MDBK cells were mock-treated (lane 1), or incubated with 50 μg/ml poly (I-C) in culture medium (lane 2) or infected with 100 HAU/ml SeV for 16h (lane 3) prior to cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of bovine (bv) ISG15, MxA, IRF-3 and actin. A nonspecific band (*) detected by the anti-MxA antiserum indicated equal loading. B. MDBK Cells were mock-infected (lanes 1 and 2) or infected with BVDV NADL (MOI=10, lanes 3 and 4) for 8h and subsequently mock-challenged (lanes 1 and 3) or challenged with SeV (lanes 2 and 4) for 16h followed by cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of bv ISG15, MxA, IRF-3, SeV, BVDV NS3, and actin.

Importantly, expression of the bovine IRF-3 protein was reduced to nearly undetectable levels in MDBK cells infected with BVDV NADL (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 3 vs. 1). In contrast, IRF-3 protein level did not change in cells infected with SeV (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 vs. 1). We conclude from these data that infection of cells with a cpBVDV ablates the virus activation of IFN responses, at least in part, by severely down-regulating the abundance of IRF-3.

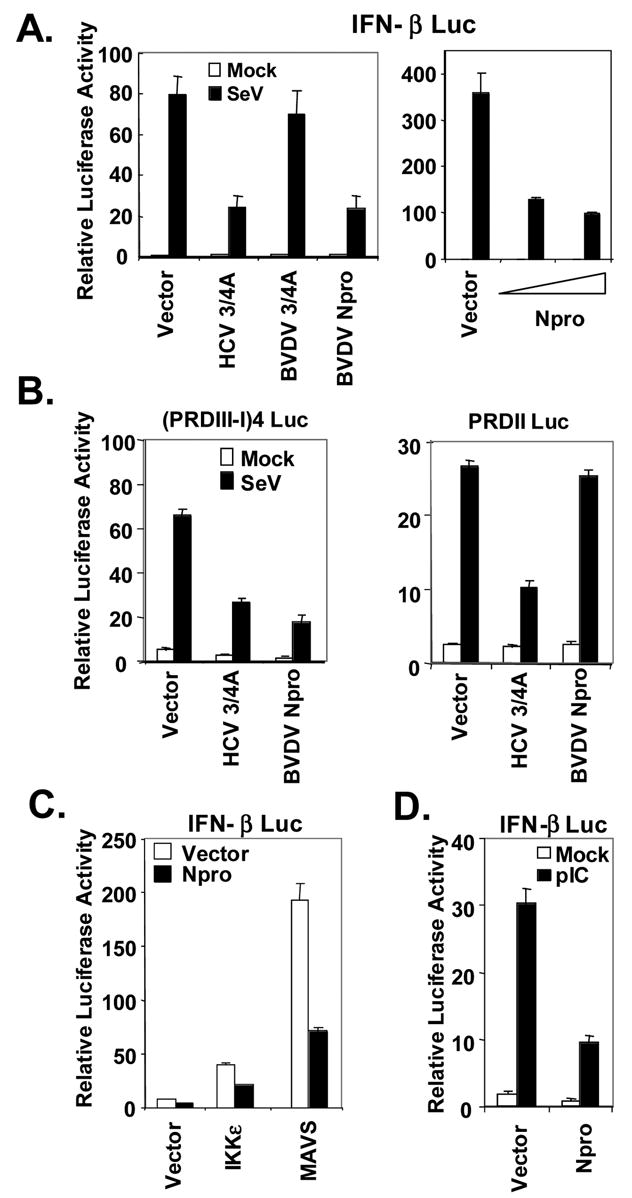

Npro inhibits activation of IRF-3-dependent promoters by acting downstream of the IRF-3 kinases

The fact that infection with either ncp or cpBVDV inhibits virus-induced IFN response suggests that BVDV expresses one or more proteins that disrupt IFN-signaling pathways, most likely by down-regulating the abundance of IRF-3. Previous studies have suggested a role for BVDV Npro as an IFN antagonist, although the underlying mechanism(s) have not been well characterized (Gil et al., 2006; Horscroft et al., 2005). Consistent with this, we found that ectopic expression of the NADL Npro protein in HEK293 cells strongly inhibited SeV activation of the IFN-β promoter in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained when the ISG56 promoter was used as a reporter (data not shown). As transcriptional induction of the IFN-β promoter involves coordinate activation of both the IRF-3 and NF-κB transcription factors (Sen, 2001), we investigated the effect of Npro expression on SeV-activation of the IRF-3-reponsive PRDIII-I and NF-κB-dependent PRDII elements of the human IFN-β promoter. As shown in Fig. 2B, ectopic expression of Npro effectively blocked SeV-induced activation of the PRDIII-I promoter, but had no demonstrable effect on activation of the PRDII promoter. Similar results were obtained when ectopic expression of the constitutively active RIG-I CARD was used in place of SeV infection to trigger the signaling (data not shown). These results contrast sharply with the impact of the HCV and GBV-B NS3/4A proteases on these pathways, as they strongly inhibit the activation of both promoters (Fig. 2B) (Chen et al., 2007; Foy et al., 2005), and suggest that Npro specifically inhibits expression of IRF-3-dependent genes downstream of RIG-I.

Fig. 2.

BVDV NADL Npro inhibits the activation of IRF-3-dependent promoters initiated by either RIG-I or TLR3 pathways. A. In left panel, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with IFN-β-Luc and pCMVβgal plasmids, and plasmids encoding HCV NS3/4A (positive control), or BVDV NS3/4A, or BVDV Npro, or a control vector. Twenty-four hours later, cells were either mock-infected (empty bars) or infected with SeV at 100 HAU/ml for 16h (solid bars) prior to lysis for both luciferase and β-galactosidase assays. Bars show relative luciferase activity normalized to β-galactosidase activity, i.e., IFN-β promoter activity. Right panel shows IFN-β promoter activity in 293T cells transfected with increasing amounts (0, 0.1 and 0.3μg) of Npro-expressing plasmid supplemented with a control vector to keep the total amount of DNA transfected constant, then mock-infected or infected with SeV. B. Activation of IRF-3-dependent PRDIII-I promoter (4-time repeat of the PRDIII-I element, left) or NF-κB-dependent PRDII promoter (right) in TH1 cells expressing HCV NS3/4A (positive control), BVDV Npro, or a control vector, and mock-infected (empty bars) or infected with SeV (solid bars). C. Activation of IFN-β promoter by ectopic expression of IKKε or MAVS in HEK293 cells in the presence of ectopic co-expression of Npro (solid bars) or a control vector (empty bars). D. IFN-β promoter activity in 293-TLR3 cells transfected with a control vector or Npro, and mock-treated (empty bars) or incubated with 50 μg/ml poly (I-C) in culture medium for 8h (Solid bars).

As RIG-I signaling bifurcates at the adaptor protein MAVS, either to the noncanonical IκB kinases, TBK1 and IKKε leading to the phosphorylation and activation of IRF-3, or to the classical IKK complex that results in the activation of NF-κB (Kawai et al., 2005; Meylan et al., 2005; Seth, Sun, and Chen, 2006; Xu et al., 2005), we postulated that Npro acts at or below the level of TBK1 and IKKε as it only affects the IRF-3 response. Consistent with this, we found that Npro strongly inhibited activation of the IFN-β promoter by ectopically expressed MAVS (Fig. 2C), or by ectopic expression of either of the IRF-3 kinases, IKKε (Fig. 2C) or TBK1 (data not shown). Ectopically expressed Npro also inhibited extracellular poly (I-C)-induced IFN-β promoter activity in HEK293 cells stably expressing TLR3 (293-TLR3 cells, Fig. 2D), consistent with the requirement for TBK1 and IKKε in activation of IRF-3 through the TLR3 pathway (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Sharma et al., 2003). Similar results were obtained when TRIF was expressed ectopically in lieu of extracellular poly (I-C) as a means to activate TLR3 signaling (data not shown). Collectively, these data indicate that the BVDV Npro specifically disrupts IRF-3-dependent innate defenses triggered by both RIG-I and TLR3 by acting downstream of the IRF-3 kinases. This is consistent with the loss of IRF-3 expression observed in BVDV NADL-infected MDBK cells (Fig. 1B).

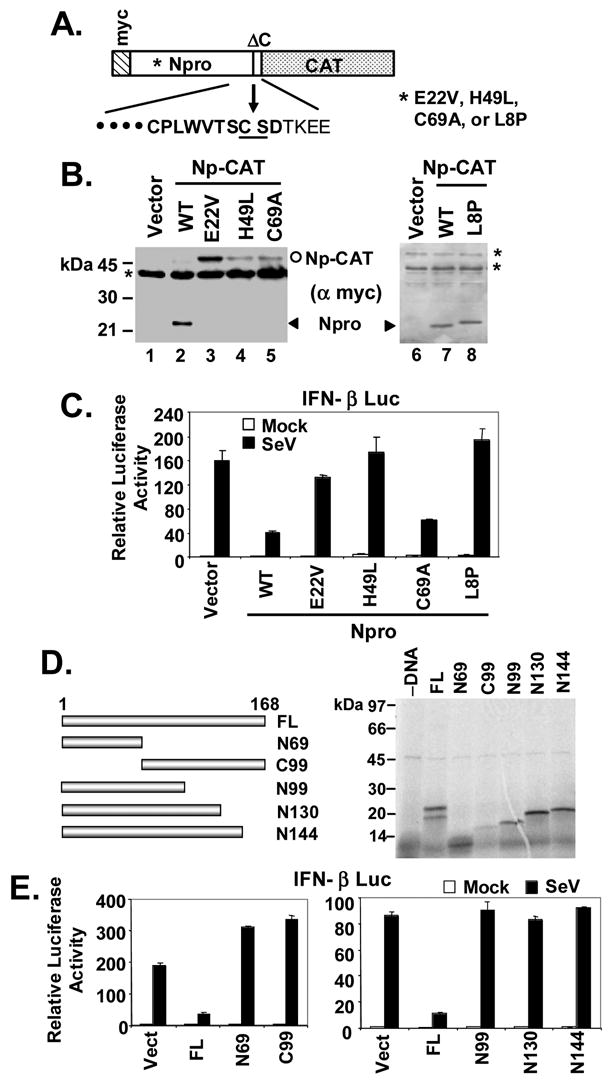

The full-length Npro protein, but not Npro protease activity, is required for inhibition of IFN responses

We next sought to determine whether the protease activity of Npro is required for its inhibition of the IFN response, a property that is shared by HCV and GBV-B NS3/4A serine proteases (Chen et al., 2007; Foy et al., 2003). Npro is a papain-like cysteine protease that contains a triad active site, Glu22-His49-Cys69 activity (Rumenapf et al., 1998). Mutations at any of these 3 residues abolish the protease activity of Npro. To determine whether this protease activity is required for Npro disruption of the viral activation of the IFN-β promoter, we constructed vectors expressing Npro mutants with active site substitutions: E22V, H49L, or C69A. We confirmed that these mutants were indeed deficient in protease activity by constructing several Np-CAT fusion constructs in which a c-myc tag and a CAT reporter gene were fused to the N- and C-termini of Npro, respectively, with the Npro cis-cleavage site reconstructed between Npro and CAT (Fig. 3A). The wild-type (WT) Np-CAT fusion construct, when ectopically expressed in HEK293 cells, auto-processed to mature Npro (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 7) and CAT (not shown), respectively. However, mutant Np-CAT constructs carrying individual active site substitutions (E22V, H49L, or C69A) were expressed exclusively as unprocessed Np-CAT fusion proteins (Fig. 3B, lanes 3–5), confirming that each of these 3 residues is essential for the activity of the Npro protease. When ectopically expressed in HEK293 cells, the E22V and H49L mutant Npro did not inhibit viral induction of IFN-β promoter, while the C69A mutant remained capable of disrupting the IFN response (Fig. 3C). These data confirm previous studies indicating that Npro protease activity is not required for disruption of the IFN response, and are concordant with a recent report in which mutated cpBVDVs carrying similar E22L or H49V mutations in Npro induced IFN in cell culture, while a C69A mutant did not (Gil et al., 2006). We speculated that the E22V and H49L substitutions may ablate the effect of Npro on IFN induction by altering the folding/conformation of Npro independent of their disruption of the protease active site. To confirm this, we characterized the ability of another previously described Npro mutant, L8P, which retains catalytic activity but is likely to have altered folding within the N-terminal domain due to the nonconservative nature of the amino acid substitution. cpBVDV carrying an L8P Npro mutant was shown to induce IFN in cell culture (Gil et al., 2006). We confirmed that L8P Npro retained protease activity (Fig. 3B, lane 8), and demonstrated that it no longer inhibited virus activation of the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 3C). Importantly, L8P Npro migrated more slowly than WT Npro in denaturing SDS-PAGE (Figs 3B, 4B and 7C), most likely due to altered conformation. Taken together, these results confirm recent reports from other laboratories that BVDV disruption of the IFN response does not require Npro protease activity (Gil et al., 2006; Hilton et al., 2006). Additional analyses with Npro deletion mutants demonstrated that constructs expressing only residues 1-69 (Npro-N69) or 99–168 (Npro-C99) of Npro lacked the ability to disrupt IFN responses (Figs. 3D and 3E). This was also the case with a mutant lacking only 24aa from the C-terminus of Npro (Npro-N144). These results are consistent with data published recently by Hilton et al. (Hilton et al., 2006) which demonstrated that removal of 30 residues from the N-terminus or 88 residues from the C-terminus abolished the IFN-inhibitory function of a ncp pe515 Npro, and indicate that the nearly full-length sequence of Npro is required for its function as an IFN antagonist.

Fig. 3.

The full-length Npro protein, but not its protease activity, is required for inhibition of IFN response. A. Schematic representation of the Npro-CAT (Np-CAT) fusion constructs with or without various point mutations in Npro. Letters in bold face at below represent the consensus sequence of Npro protease recognition site. B. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector or individual Np-CAT constructs encoding the WT sequence or carrying various point mutations, and subsequently lysed for immunoblot analysis using an anti-myc-tag antibody. The positions of mature Npro and unprocessed Np-CAT were marked by arrow head and circle, respectively. * denotes nonspecific bands. Note that the L8P mutant Npro (lane 8) migrated slightly slower than WT Npro (lanes 2 and 7). C. IFN-β promoter activity in HEK293 cells transfected with an empty vector, or WT Npro, or the indicated Npro point mutants, and then mock-infected or infected with SeV. D. Left panel, schematic representation of full-length (FL) Npro and various Npro truncation mutants. Numbers indicate aa positions from N-terminus except that C99 represents the C-terminal 99aa. Right panel shows SDS-PAGE of in vitro translated products of the individual Npro constructs shown in left panel. Full-length (FL) Npro and the individual Npro deletion mutants were expressed in vitro and labeled with [35S]-Met using the TNT T7 Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. E. IFN-β promoter activity in HEK293 cells transfected with an empty vector, or FL Npro, or the indicated Npro truncation mutants, and mock-infected or infected with SeV.

Fig. 4.

Ectopic expression Npro reduces IRF-3 protein abundance and inhibits the induction of IRF-3 target genes. A. HeLa cell lines with tet-regulated expression of WT Npro (Npro-25 and Npro-29 cells, left panel) or L8P mutant Npro (L8P-1, right panel) were cultured to repress (+tet) or induce (-tet) Npro expression for 3 days, followed by mock infection or infection with 100 HAU/ml SeV for 16h prior to cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of whole cell extracts for IRF-3, ISG56, SeV, Npro (using an anti-myc tag antibody) and actin. B. Populations of MDBK cells with stable expression of a control vector (Pur, lanes 1 and 2), WT Npro (Npro, lanes 5 and 6) or L8P mutant Npro (L8P, lanes 3 and 4) were mock-infected (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or infected with SeV (lanes 2, 4, and 6) for 16h before cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of bv IRF-3 and ISG15, SeV and actin. WT and L8P mutant Npros were detected with an anti-myc tag antibody and their positions were marked by line and arrow, respectively. C. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of IFN-β mRNA transcripts in HeLa Npro-29 cells repressed or induced for Npro expression, and mock-infected or infected with SeV. mRNA abundance was normalized to cellular 18S ribosomal RNA. D. Npro-29 cells repressed (+tet) or induced (-tet) for Npro expression were mock-treated or incubated with 50 μg/ml poly (I-C) in culture medium for 15h before cell lysis for immunoblot analysis of ISG56, IRF-3, Npro and actin.

Fig. 7.

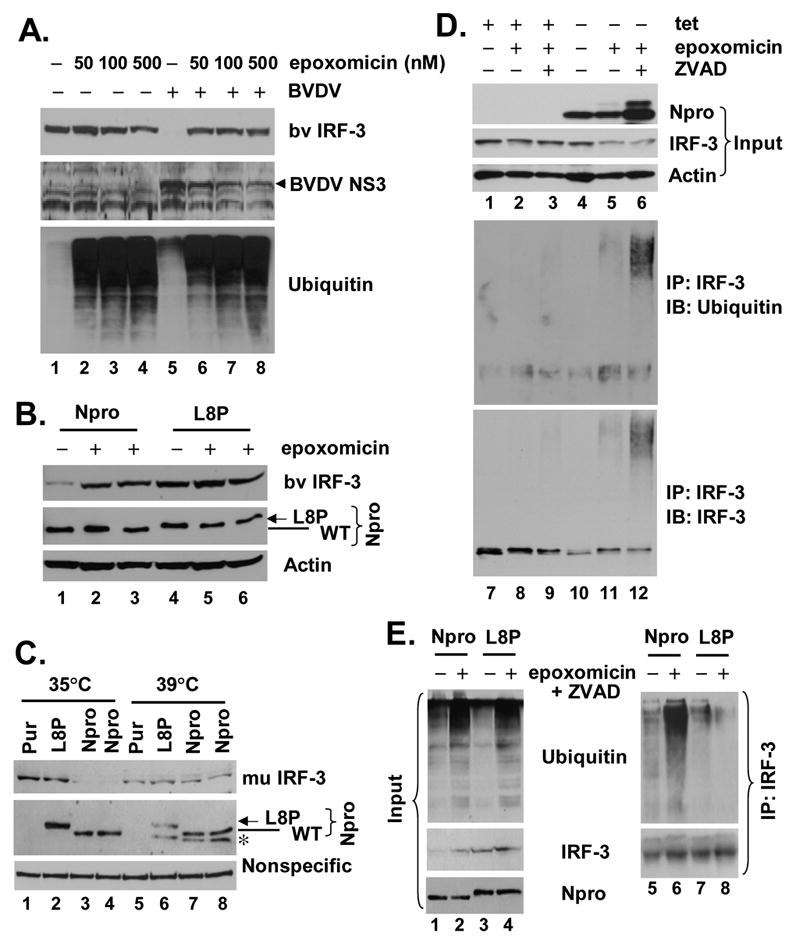

Npro induces IRF-3 polyubiquitination and its subsequent degradation through a proteasome-dependent pathway. A. MDBK cells were mock-infected (lanes 1 through 4) or infected with BVDV NADL at an MOI=10 (lanes 5 through 8). 3h later, cells were mock-treated or incubated with indicated concentrations of epoxomicin for further 20h before cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of bv IRF-3, BVDV NS3, and ubiquitin. B. MDBK cells with stable expression of WT NADL Npro (lanes 1 through 3) or L8P mutant Npro (lanes 4 through 6) were cultured in the presence (lanes 2, 3, 5 and 6) or absence (lanes 1 and 4) of 40nM epoxomicin for 20h before cell lysis and immunoblot analysis of bv IRF-3, Npro (using an anti-myc tag antibody) and actin. C. Thermal inactivation of the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme prevented the loss of IRF-3 protein in the presence of Npro. ts20-derived cell populations with stable expression of control vector (Pur), L8P mutant Npro (L8P), or WT NADL Npro (Npro) were either cultured at 35°C or 39°C for 16h prior to whole cellular extract preparation and immunoblot analysis of murine IRF-3, Npro (using an anti-myc tag antibody). A nonspecific band detected by the anti-IRF-3 antibody was shown to indicate equal loading. Although its nature remains unknown, a protein band (marked by “*”) was detected by the anti-myc antibody and only present in cells expressing WT or L8P Npro and cultured at 39°C. D. Npro-25 cells that were repressed (+tet) or induced (-tet) for Npro expression were mock-treated, or treated with 50nM epoxomicin, and where indicated, along with 40 μM ZVAD, a pan-caspase inhibitor, to enhance cell viability. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation with a rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody. The immunoprecipitates were extensively washed, followed by immunoblot analysis using an mAb anti-ubiquitin (middle-panel) and an mAb anti-IRF-3 (lower panel). One tenth of the protein lysates (input) were subjected to immunoblot analysis of Npro (using an anti-myc tag antibody), IRF-3 and actin (upper panels). E. MDBK cells with stable expression of WT Npro (Npro, lanes 1, 2, 5 and 6) or L8P mutant Npro (L8P, lanes 3, 4, 7 and 8) were cultured in the presence (lanes 2, 4, 6 and 8) or absence (lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7) of epoxomicin and ZVAD. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoblot analysis for ubiquitin, IRF-3, and Npro/L8P (with an anti-myc tag mAb) (left panels, lanes 1 through 4), or processed for IRF-3 immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblot analysis for ubiquitin (upper right panel). The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed for IRF-3 (lower right panel).

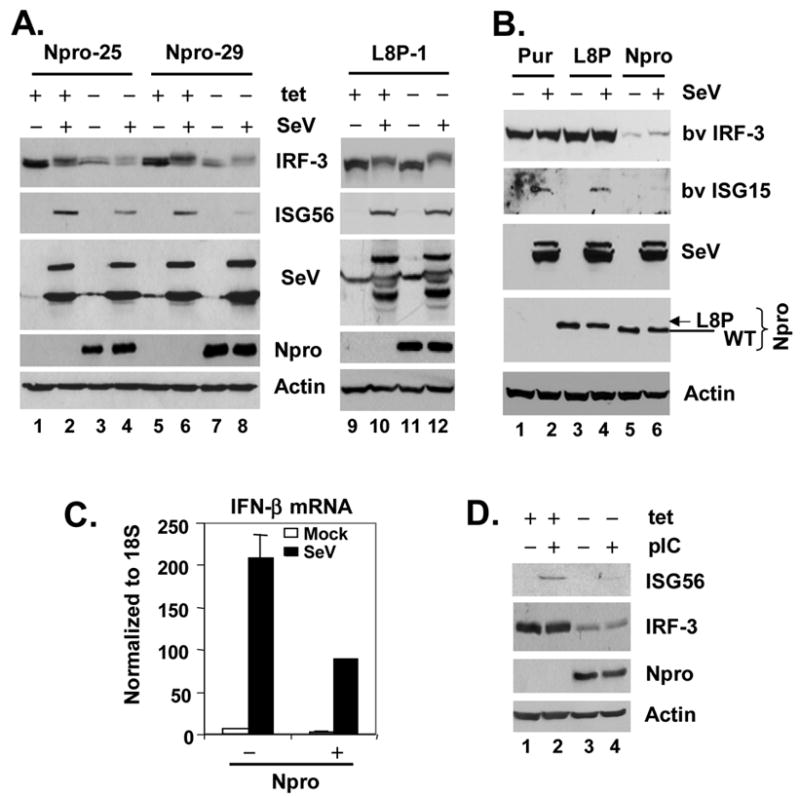

Npro down-regulates IRF-3 protein abundance but does not affect virus-induced IRF-3 activation

To better characterize the role of Npro in antagonizing the IFN response and potentially down-regulating IRF-3 abundance, we developed HeLa cell lines that conditionally express NADL Npro, and as controls, the L8P mutant Npro, using the Tet-Off gene expression system. We selected two WT Npro-inducible cell lines, Npro-25 and Npro-29, and three L8P mutant Npro-inducible cell lines, L8P-1, -22 and -38, for further analysis. As seen in Fig. 4A, the expression of Npro (WT or L8P) was tightly regulated by tetracycline, occurring when these cells were cultured in its absence (data from Npro-25, -29 cells and L8P-1 cells were shown). We also established stably transduced MDBK cells with constitutive expression of WT (BK-Npro), L8P Npro (BK-L8P), or the control vector (BK-Pur), using retroviral-mediated gene transfer (Fig. 4B).

Consistent with the reporter data, we found that SeV-induced ISG56 expression was significantly reduced in both Npro-25 and Npro-29 cells when WT Npro expression was de-repressed (-tet) (Fig. 4A, ISG56 panel, compare lanes 4 vs. 2 and 8 vs. 6). In contrast, induction of the L8P mutant Npro had little effect on SeV-activated ISG56 expression in L8P-1 (Fig. 4A, ISG56 panel, compare lanes 12 vs. 10), L8P-22, and L8P-38 cells (data not shown). Similar inhibition of SeV-induced bovine ISG15 expression was observed in BK-Npro cells that constitutively express WT Npro, but not in the related BK-L8P or BK-Pur cells (Fig. 4B). Using real-time PCR analysis, we also confirmed that Npro expression significantly reduced SeV-induced IFN-β mRNA transcripts in Npro-29 cells (Fig. 4C). We also observed that the induction of ISG56 expression in response to extracellular poly(I-C) was significantly reduced by Npro expression (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 4 vs 2), confirming that Npro also inhibits the expression of endogenous IRF-3 target genes following TLR3 engagement.

Importantly, the induction of Npro expression led to a significant reduction in IRF-3 protein abundance in both Npro-25 and 29 cells (Fig. 4A, IRF-3 panel, compare lanes 3 vs. 1 and 7 vs. 5, and Fig. 4D, compare lanes 3 vs. 1), while Npro expression was associated with reduced IRF-3 abundance in the stably transduced BK-Npro cells (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 5 and 6 vs. 1 and 2). In contrast, this was not observed in L8P mutant-expressing cells, L8P-1 (Fig. 4A, compares lanes 11 vs. 9), L8P-22 and L8P-38 cells (data not shown), or BK-L8P cells (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 3 and 4 vs. 1 and 2). The abundance of RIG-I, TBK1, or IKKε was not affected by Npro expression in Npro-29 cells (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that the expression of Npro down-regulates the abundance of IRF-3, and that this is responsible for the disruption of virus-induced IFN responses in cells infected with cpBVDV.

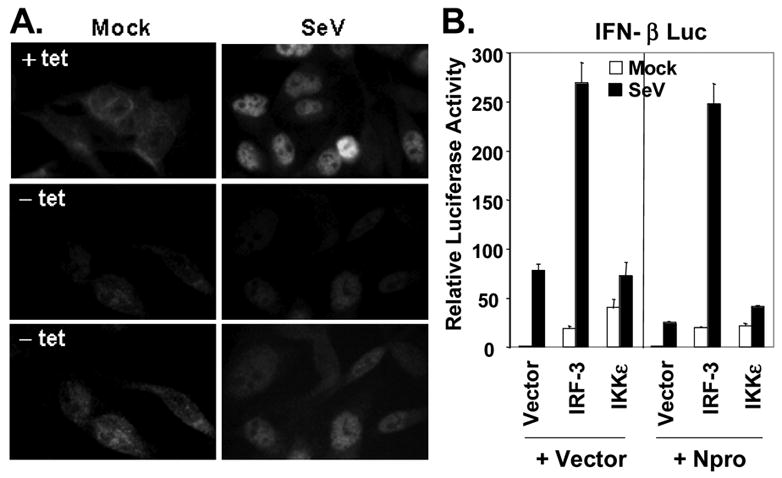

Importantly, despite the reduction in protein expression, the residual IRF-3 was still phosphorylated following SeV infection in NADL Npro-expressing cells (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 vs. 4, and 7 vs. 8). To confirm that NADL Npro expression does not affect the activation of IRF-3, we studied the tet-inducible cell lines for evidence of virus-induced IRF-3 nuclear translocation and association of IRF-3 with CBP, both well characterized indicators of IRF-3 activation (Lin et al., 1998). We found that IRF-3 remained capable of translocating to the nucleus following SeV challenge in cells expressing Npro (Fig. 5A). The percentage of SeV-infected cells with nuclear IRF-3, however, was less in cells induced for Npro expression (-tet), probably as a result of decreased IRF-3 abundance which rendered the detection of nuclear IRF-3 more difficult (data not shown). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that the residual IRF-3 was also capable of associating with CBP upon SeV challenge, regardless of Npro expression status, in both Npro-25 and -29 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, ectopic expression of IRF-3, but not IKKε, was able to overcome the Npro disruption of SeV activation of the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 5B), suggesting that IRF-3 can be activated upon virus infection in the presence of NADL Npro. These results suggest that NADL Npro disrupts IFN responses by reducing the available levels of IRF-3, and that NADL Npro does not seem to alter the activation pathways that control IRF-3 phosphorylation, nuclear translocation or the induction of IFN-β transcription. These results contrast with those reported by Hilton et al. in studies using HEp2 cells stably expressing ncp-pe515 Npro, in which Npro also inhibited IRF-3 binding to DNA (Hilton et al., 2006). Further investigation will be needed to determine whether this discrepancy is related to cell type differences and/or differences in the Npro amino acid sequences (about 8%) of the viral strains used in the two studies.

Fig. 5.

NADL Npro does not affect virus-induced IRF-3 activation. A. Immunofluorescence staining of IRF-3 in Npro-25 cells, repressed (+tet, upper panels) or induced (-tet, middle and lower panels) for Npro expression, and mock infected (left panels) or infected with SeV (right panels) for 16h. Exposure time was kept constant when pictures were taken for upper and middle panels. The lower panels represent prolonged exposure of the middle panels to better demonstrate the IRF-3 localization. B. Activation of IFN-β promoter by ectopic expression of IRF-3, IKKε, or a control vector in HEK293 cells cotransfected with an empty vector or Npro-expressing plasmid. 20h later, transfected cells were mock-infected or infected with SeV for 16h before cell lysis for luciferase and β-galactosidase assays.

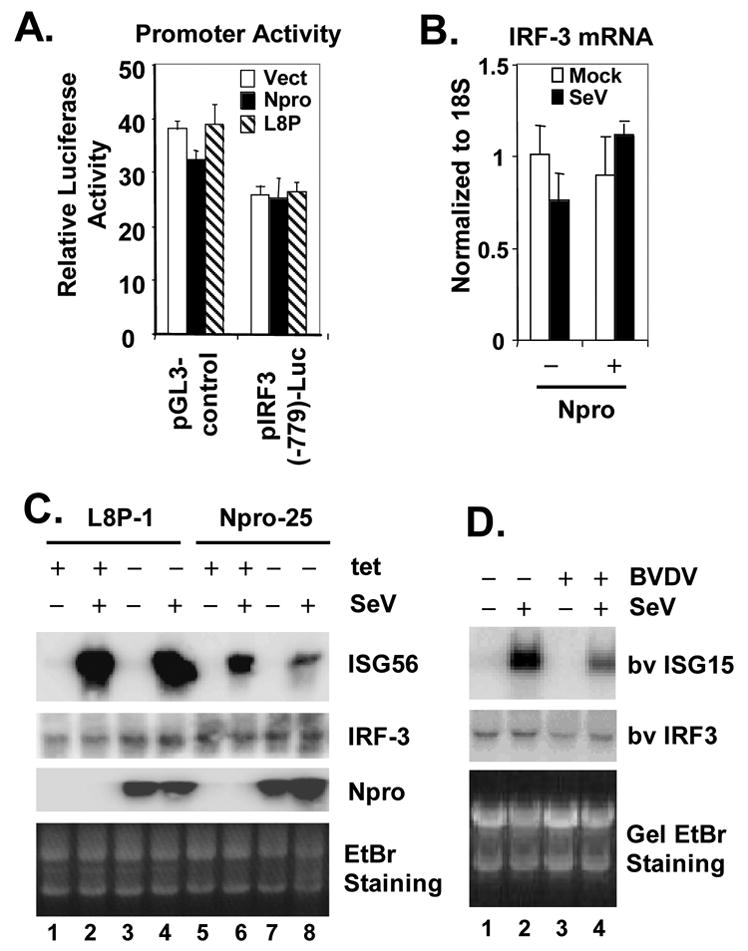

Npro down-regulates IRF-3 at a post-transcriptional level

Next, we asked whether IRF-3 transcription is down-regulated by NADL Npro. This seemed likely, as the CSFV Npro has been reported to down-regulate IRF-3 mRNA transcription (La Rocca et al., 2005). IRF-3 is constitutively expressed, and its activity and steady-state abundance are known to be regulated mainly by post-transcriptional modifications, such as phosphorylation and proteasome-mediated degradation, usually following viral infections (Lin et al., 1998; Lowther et al., 1999). Using a promoter based reporter assay, we found that the human IRF-3 promoter [in pIRF3(-779)-Luc] was constitutively active, similar to the strong SV40 promoter (in pGL3-control), and that its activity was not affected by co-expression of the WT or L8P mutant Npro (Fig. 6A). Real-time PCR analysis confirmed that IRF-3 mRNA levels did not change following the induction of Npro expression and/or SeV infection in Npro-29 cells (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, northern blot analyses showed that the abundance of IRF-3 mRNA was not reduced in cells expressing the WT or L8P mutant Npro (Fig. 6C), although WT Npro expression significantly reduced virus-induced ISG56 mRNA levels (Fig. 6C). Finally, despite the ablation of IRF-3 protein expression in cpBVDV NADL-infected MDBK cells (Fig. 1B), there was little change in the abundance IRF-3 mRNA abundance (Fig. 6D). As expected, the cpBVDV-infected cells showed a significant reduction in the abundance of SeV-induced bovine ISG15 mRNA (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data indicate that, in contrast to the results reported by La Rocca et al previously (La Rocca et al., 2005), the Npro of cpBVDV does not inhibit IRF-3 mRNA transcription but rather down-regulates IRF-3 post-transcriptionally.

Fig. 6.

Npro down-regulates IRF-3 expression at post-transcriptional level. A. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with pCMVβgal (internal control) and pGL3-control (driven by SV40 promoter, left) or pIRF3(-779)-Luc (right), and plasmids encoding WT Npro (solid bars), or L8P mutant Npro (hatched bars), or a control vector (empty bars). 24h later, cells were lysed for both luciferase and β-galactosidase assays. B. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of IRF-3 mRNA transcript in HeLa Npro-29 cells repressed or induced for Npro expression, and mock-infected or infected with SeV. mRNA abundance was normalized to cellular 18S ribosomal RNA. C. L8P-1 and Npro-25 cells were repressed (+tet) or induced (-tet) for Npro (L8P mutant or WT, respectively) expression for 3 days, followed by mock-infection (lanes 1, 3, 5 and 7) or challenge (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) with SeV for 8h prior to total RNA extraction and northern blot analysis of ISG56, IRF-3 and Npro mRNAs. An ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining image of the RNA gel was included to show equal loading of the RNA samples. D. MDBK Cells were mock-infected (lanes 1 and 2) or infected with BVDV NADL (MOI=10, lanes 3 and 4) for 8h and subsequently mock-infected (lanes 1 and 3) or challenged with SeV (lanes 2 and 4) for 16h. Total cellular RNA was isolated, fractionated on denaturing gel, followed by northern blot analysis of bv ISG15 and IRF-3. An ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining image of the RNA gel was included to show equal loading of the RNA samples.

Npro induces polyubiquitination of IRF-3 and promotes proteasome-mediated degradation of IRF-3

The ubiquitin-proteasome degradation pathway represents a major, non-lysosomal protein degradation system that regulates the expression of many proteins involved in diverse cellular processes (Liu, Penninger, and Karin, 2005). It is known to play a role in controlling IRF-3 abundance, and SeV infection is known to induce the proteasomal degradation of IRF-3 in some cell types (Lin et al., 1998). To determine whether Npro induces the proteasome-dependent degradation of IRF-3, we treated NADL-infected MDBK cells with increasing concentrations of epoxomicin, a potent mammalian 26S proteasome inhibitor (Meng et al., 1999), and determined bovine IRF-3 protein levels by immunoblot analysis. As shown in Fig. 7A, treatment with as little as 50 nM epoxomicin dramatically restored the abundance of IRF-3 in NADL-infected cells, but had little effect on IRF-3 abundance in non-infected cells. This was accompanied by an accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated cellular proteins, demonstrating the effectiveness of epoxomicin in inhibiting the proteasome. At 50 nM concentration, epoxomicin had little effect on BVDV replication, as expression of BVDV NS3 was minimally affected (Fig. 7A, compare lanes 5 vs. 6). At higher concentrations (100 and 500 nM), epoxomicin decreased the BVDV NS3 protein levels, presumably as a result of cell toxicity (Fig. 7A, lanes 7 and 8). Treatment with 40 nM epoxomicin also restored the IRF-3 abundance in MDBK cells stably expressing NADL Npro (Fig. 7B, IRF-3 panel, compare lanes 2 and 3 vs. 1). MG115, an alternative 26S proteasome inhibitor, also significantly elevated IRF-3 protein levels in Npro-expressing MDBK cells, but was more toxic than epoxomicin (data not shown). These results are consistent with ncp pe515 Npro-mediated proteasome-dependent degradation of IRF-3, as recently reported by Hilton et al. (Hilton et al., 2006).

We next sought to determine whether Npro-mediated down-regulation of IRF-3 abundance is dependent on the polyubiquitination of IRF-3, a step required for many (but not all) proteins to be degraded via the proteasome (Liu, Penninger, and Karin, 2005). To assess this possibility, we utilized murine fibroblast ts20 cells which express a temperature-sensitive E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme (Chowdary et al., 1994). When ts20 cells are shifted from a permissive temperature (35°C) to a restrictive temperature (39°C), the E1 ubiquitin-activating protein is inactivated and as a result, cells fail to degrade proteins that are degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Chowdary et al., 1994). We first made stable populations of ts20 cells that express WT Npro, and as controls, the L8P Npro mutant and related vector (Pur), respectively, using retroviral gene transfer. We then compared the IRF-3 protein abundance in these cells when they were cultured at either 35°C or 39°C. As shown in Fig. 7C, when cells were cultured at 35°C, detectable IRF-3 protein expression was nearly completely ablated in Npro-expressing ts20 cells, compared with cells expressing the related L8P mutant or empty vector (compare lanes 3 and 4 vs. 1 and 2). However, there was no difference in the abundance of IRF-3 protein in these cells when they were cultured at the restrictive temperature, 39°C, at which the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme expressed by ts20 cells is inactive (compare lanes 7 and 8 vs. 5 and 6). These data unambiguously demonstrate that ubiquitination is an indispensable step in Npro-induced IRF-3 degradation.

As these experiments were in progress, Hilton et al. (Hilton et al., 2006) reported that Npro from a ncpBVDV (pe515 strain) targets IRF-3 for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in HEp2 cells (Hilton et al., 2006). They showed that co-treatment of cells with ZAVD-fmk, a general caspase inhibitor, improved the viability of cells treated with a proteasome inhibitor, probably by blocking the apoptosis induced by a variety of chemical inhibitors of the proteasome (Nencioni et al., 2005). We used this approach to demonstrate that cpNADL Npro induces IRF-3 polyubiquitination in our tet-regulated Npro HeLa cells (Fig. 7D). Combined treatment of Npro-expressing (-tet) cells with epoxomicin and ZVAD resulted in a heterogeneous high molecular mass protein complex that could be immunoprecipitated by antibody to IRF-3 and reacted with antibody to ubiquitin (Fig. 7D). This was evident in Npro-expressing cells treated only with epoxomicin, but was more readily detected in cells treated with both epoxomicin and ZVAD (Fig. 7D, compare lanes 11 vs. 12). No high mass complex was evident in the absence of Npro expression even in cells treated with both epoxomicin and ZVAD. These observations were also confirmed in MDBK cells. While WT Npro induced the polyubiquitination of IRF-3, the L8P mutant Npro failed to do so under similar conditions (Fig. 7E), consistent with its inability to down-regulate IRF-3 (Fig. 4A, 4B, and 7C). Thus, in agreement with recent observations concerning the Npro from a ncpBVDV strain (Hilton et al., 2006), cp NADL Npro also induces polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IRF-3. Importantly, these results also demonstrate that the inability of a mutant Npro (L8P) to induce IRF-3 degradation parallels its inability to target IRF-3 for polyubiquitination (Fig. 7E). This is consistent with the data shown in Fig. 7C, which indicate that Npro-mediated IRF-3 proteasomal degradation requires the polyubiquitination of IRF-3.

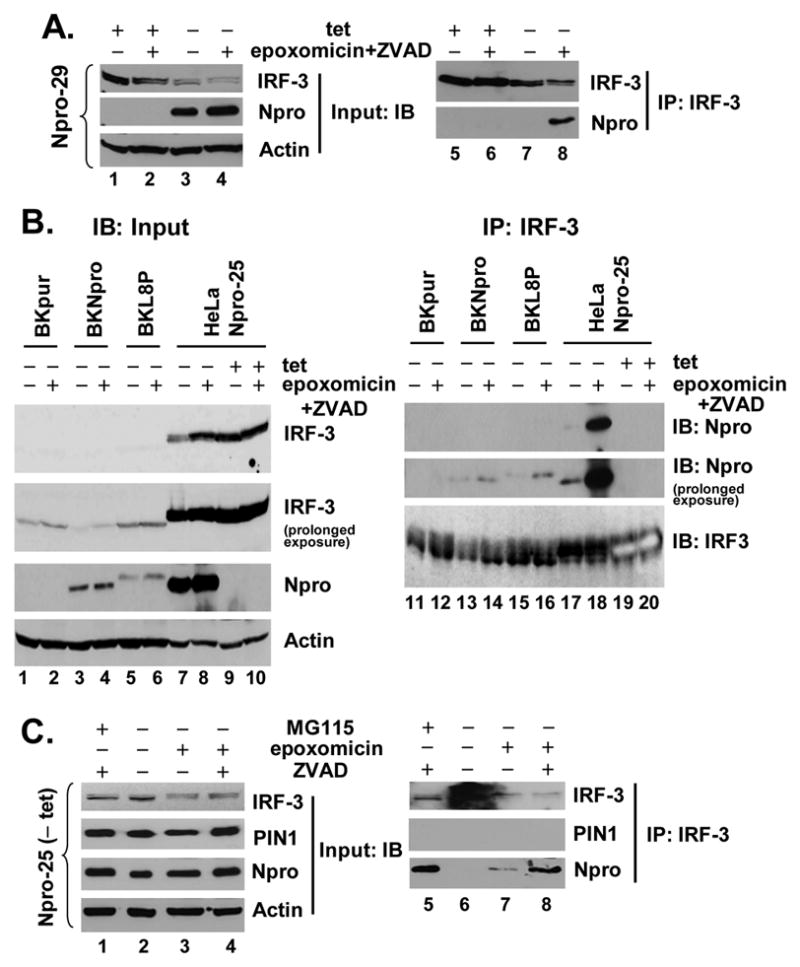

Npro interacts with IRF-3

To characterize the mechanism by which Npro induces IRF-3 polyubiquitination, we asked whether Npro physically interacts with IRF-3. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments did not demonstrate the NADL Npro to be associated with IRF-3 in either the Npro-29 (Fig. 8A, lane 7) or Npro-25 (Fig. 8C, lane 6) cells under normal culture conditions. These data are similar to those reported recently by Hilton et al (Hilton et al., 2006) with the ncp-pe515 Npro. However, we observed that Npro reproducibly co-precipitated with IRF-3 when cells were treated with either of two different proteasome inhibitors, MG115 or epoxomicin, with or without concomitant ZVAD (Fig. 8A, lane 8 and Fig. 8C, lanes 5, 7, and 8). In agreement with these data, we found that Npro interacts with IRF-3 in MDBK cells stably expressing Npro. While difficult to detect under normal culture conditions, this interaction was much more easily demonstrated following inhibition of the proteasome (Fig. 8B, compare lanes 14 vs. 13). Interestingly, the L8P mutant Npro was also able to interact with IRF-3 under similar conditions (Fig. 8B, lanes 15 and 16), indicating that its inability to induce IRF-3 polyubiquitination and degradation (Fig. 7E, 7C, Fig. 4A and 4B) is not due to an inability to interact with IRF-3. In aggregate, these data suggest that wild-type Npro, but not the L8P mutant, is capable of recruiting an additional cellular protein, perhaps an E3 ubiquitin ligase, that is essential for polyubiquitination of IRF-3. Although PIN1 has been reported to be recruited to IRF-3 and to be essential for proteasomal degradation of IRF-3 following dsRNA stimulation or SeV infection (Saitoh et al., 2006), we found no evidence for an interaction of PIN1 with IRF-3 under these conditions (Fig. 8C),. These data, together with that Npro down-regulates IRF-3 in the absence of virus infection (Figs. 4 and 7C), suggest that Npro induces the polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of IRF-3 via a PIN1-independent mechanism.

Fig. 8.

Npro, but not PIN1, interacts with IRF-3 in the presence of proteasome inhibition. A. Npro-29 cells repressed (+tet) or induced (-tet) for Npro expression were mock treated or treated with 50 nM of epoxomixin along with 40 μM ZVAD, similarly to Fig. 7D. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody followed by immunoblot analysis with mAb anti-IRF-3 or anti-myc tag (Npro) (right panels). Immunoblot analysis of the input (left panels) was conducted similarly as Fig. 7C. B. MDBK cells stably expressing the control vector (BKpur, lanes 1, 2, 11 and 12), Npro (BKNpro, lanes 3, 4, 13 and 14), or the mutant L8P Npro (BKL8P, lanes 5, 6, 15 and 16), and HeLa Npro-25 cells (lanes 7 through 10 and 17 through 20) with (-tet) and without (+tet) Npro expression were mock treated or treated with epoxomicin plus ZVAD. Left panels show immunoblot analysis of input for IRF-3, Npro, and actin. Note that the rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody had greater affinity for human IRF-3 (lanes 7 through 10) than bovine IRF-3 (lanes 1 through 6). In right panels (lanes 11 through 20), cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with a rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody followed by immunoblot analysis for WT or L8P Npro (using an mAb anti-myc tag), or IRF-3. The rabbit anti-IRF-3 antibody was used to probe the immunoprecipitates as the mAb anti-IRF-3 did not detect bovine IRF-3. The dark shadowing behind the bovine and human IRF-3 bands is the Ig heavy chain. Note that the human IRF-3 bands in lanes 19 and 20 (HeLa Npro-25 cells repressed for Npro expression) developed on the blot due to their higher abundance and therefore, show bands of empty space. C. Npro-25 cells induced for Npro expression (-tet) were mock-treated, or treated with 2μM MG115, or 50 nM epoxomicin, and where indicated 40 μM ZVAD. The IRF-3 immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with mAb anti-IRF-3, rabbit anti-PIN1, and mAb anti-myc tag (Npro) (right panels). Left panels show immunoblot analysis of input for IRF-3, PIN1, Npro, and actin.

Discussion

While the ability of cpBVDVs to induce IFN has been controversial (Brackenbury, Carr, and Charleston, 2003; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003; Schweizer et al., 2006), we have shown here that infection with at least one cp strain of BVDV, NADL, like ncpBVDVs, does not induce an IFN response in cell culture (Fig. 1). This is consistent with two recent reports (Gil et al., 2006; Schweizer et al., 2006). Moreover, we have demonstrated that BVDV NADL infection abrogates the IFN response triggered by SeV, which is known to activate the RIG-I signaling pathway that is essential for initiation of IFN responses to flaviviruses (Kato et al., 2006; Li et al., 2005; Yoneyama et al., 2004). Thus, the absence of an IFN response in NADL BVDV infected cells is due to the ability of NADL BVDV to actively block the host response. Although it remains to be investigated whether different cpBVDV strains may differentially modulate IFN responses, our data suggest that the disruption of IFN induction is not a unique feature of ncp BVDVs, but is also shared by at least some cpBVDV strains, e.g. the NADL strain as we have shown in this study.

Several previous studies have suggested a role for BVDV Npro as an IFN antagonist (Gil et al., 2006; Horscroft et al., 2005), but have left unanswered many questions concerning the underlying mechanisms. Our data indicate that Npro expressed during infection with a cpBVDV NADL strain inhibits host responses triggered through IRF-3, the central regulator in type I IFN synthesis, but leaves NF-κB activation of gene expression unaffected (Fig. 2). Npro accomplishes this by post-transcriptional down-regulation of IRF-3 protein abundance, thereby effectively inhibiting IRF-3 dependent antiviral gene expression initiated through either the TLR3 or RIG-I pathogen pattern recognition receptors, the two major IFN-inducing pathways present in most parenchymal cells (Akira, Uematsu, and Takeuchi, 2006). Importantly, we have demonstrated this upon transient, stable, and inducible expression of Npro as an isolated protein in cells of human, bovine, and murine origin, as well as in bovine kidney cells infected with BVDV. Very recently, Hilton et al (Hilton et al., 2006) reported similar results, showing blockade of IFN induction by Npro using primarily promoter-based reporter assays and quantitation of IFN-β mRNA. We have shown here that Npro also inhibits virus-induced expression of multiple ISGs: ISG56, ISG15, MxA and IFN-β. Nonetheless, both studies lead to the same conclusion, that Npro specifically targets the IRF-3 arm in innate antiviral responses and is a key contributor to the disruption of IFN responses by BVDV. Interestingly, the Npro of CSFV, another closely related pestivirus, has also shown to block virus-induced IFN responses (Bauhofer et al., 2007; La Rocca et al., 2005; Ruggli et al., 2005).

Using a reverse-genetics approach, Gil et al. (Gil et al., 2006) concluded that the N-terminal domain of Npro is important for its ability to block the IFN response in BVDV-infected cells, as BVDV mutants carrying substitutions within the N-terminus of Npro (L8P, E22L, and H49V) induced IFN in infected cell cultures (Gil et al., 2006). Hilton et al. recently demonstrated that both N-terminal and C-terminal domains of Npro are important, as removal of 30 aa from the N-terminus or 88 aa from the C-terminus of ncp pe515 Npro abolished its ability to inhibit dsRNA activation of IFN-β promoter (Hilton et al., 2006). Our data are in agreement with these other studies. Furthermore, we show that deletion of as few as 24 aa from the C-terminus of the NADL Npro molecule completely abrogates its ability to inhibit the IFN response (Fig. 3D and 3E). Consistent with the observation by Gil et al (Gil et al., 2006) that BVDV carrying an L8P mutation in Npro induces IFN in cell culture, we found that this catalytically-active Npro mutant is no longer able to inhibit the induction of IFN by SeV infection (Fig. 3C) or poly(I-C) (data not shown). Taken collectively, these data show that the nearly full length sequence of Npro is essential to its function in antagonizing the IFN response, while retention of Npro protease activity is not (Fig. 3). Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms by which these mutations or deletions ablate the disruption of IFN signaling by Npro, e.g., whether they do so by altering the folding/conformation of Npro or otherwise preventing its interactions with cellular protein(s) involved in the down-regulation of IRF-3, including perhaps IRF-3 itself.

We found that the cpNADL Npro down-regulates IRF-3 post-transcriptionally by inducing its polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation, either in bovine kidney MDBK cells infected with the NADL strain or constitutively expressing NADL Npro, and in HeLa cells with conditional expression of NADL Npro. These results are similar to those reported recently by Hilton et al. (Hilton et al., 2006), who demonstrated ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of IRF-3 in calf testis cells infected with a ncpBVDV strain (pe515) and in human HEp2 cells constitutively expressing ncp pe515 Npro. Thus, the ability of Npro to target IRF-3 for degradation is shared by both ncp and cpBVDVs and is not host species specific, as it occurs in both bovine and human cells. We have demonstrated in this study that Npro-dependent, proteasome-mediated degradation of IRF-3 requires prior polyubiquitination of IRF-3, as this occurred only at temperatures permissive for E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme activity in murine fibroblast ts20 cells that express a temperature-sensitive E1 mutant (Fig. 7C). This is important, as not all proteins degraded by the proteasome undergo prior polyubiquitination (Liu, Penninger, and Karin, 2005). Our data suggest that the main effect of Npro may be to direct the polyubiquitination of IRF-3, as we did not observe an accumulation of heterogenous high molecular mass IRF-3-ubiquitin complexes in epoxomicin and ZVAD-treated cells in the absence of Npro expression (Fig. 7D), nor did we see IRF-3 polyubiquitination in cells expressing the L8P mutant Npro that is incapable of downregulating IRF-3 (Fig. 7E). Our data also indicate that virus-induced phosphorylation of IRF-3 is not required for Npro-dependent IRF-3 ubiquitination, as this occurred in the absence of virus infection in HeLa cells that conditionally expressed Npro under control of a tet-regulated promoter (Fig. 7D) and in MDBK cells with constitutive expression of Npro (Fig. 7E).

The precise mechanisms by which Npro induces the polyubiquitination of IRF-3 and subsequently delivers it to proteasomes remain unknown and await further careful investigation. Previous studies have shown that a number of viruses encode proteins that hijack the degradation machinery of the proteasome to degrade cellular proteins (Chen and Gerlier, 2006). This usually involves the association of cellular targets with their viral partners, recruiting specific E3 ubiquitin ligases to the complex to catalyze polyubiquitination of the target protein, as shown for degradation of p53 by the human papilloma virus E6 protein and cellular HECT domain E3 ligase, E6AP (Huibregtse, Scheffner, and Howley, 1993). We were able to demonstrate a weak interaction between Npro and IRF-3, which was significantly enhanced when the 26S proteasome was inhibited by treatment with MG115 or epoxomicin (Fig. 8). It is possible that the interaction of IRF-3 with Npro quickly leads to its polyubiquitination and subsequent destruction via the proteasome, rendering it difficult to detect the Npro-IRF-3 complex. However, the L8P mutant Npro was also capable of interacting with IRF-3, an association that was also enhanced by proteasome inhibition (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that the interaction between IRF-3 and Npro/L8P may be stabilized by an unknown protein partner that is regulated by the proteasome. While this requires further investigation, our data indicate that the ability to interact with IRF-3 is not the sole determinant for polyubiquitination of IRF-3 by Npro. Additional cellular protein partner(s), including possibly an E3 ubiquitin ligase(s), may need to be recruited to the Npro-IRF-3 complex, and may interact efficiently with Npro but not the L8P mutant Npro. Furthermore, our data indicate that IRF-3 ubiquitination may not be a prerequisite for its interaction with Npro, as the L8P mutant, which is incapable of inducing IRF-3 ubiquitination (Fig. 7E), can also interact with IRF-3 (Fig. 8B). However, it is important to keep in mind the possibility that a low level of IRF-3 ubiquitination, below the limits of detection in our assay, may be needed for its recognition by Npro.

While we have shown that the Npro-dependent polyubiquitination of IRF-3 requires the E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme (Fig. 7C), the responsible E3 ligase remains to be identified. Current understanding of the manner in which IRF-3 abundance is regulated by the proteasome is limited. SeV infection triggers C-terminal phosphorylation of IRF-3, which is followed by its proteasome-dependent degradation (Lin et al., 1998). However, these events may differ in different cell types (Foy et al., 2003). Some evidence suggests that a cullin1-based ubiquitin ligase is involved in the regulation of IRF-3 in SeV infected cells following its C-terminal phosphorylation by TBK1 (Bibeau-Poirier et al., 2006). However, other data suggest that the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase PIN1 is recruited to phosphorylated IRF-3 and essential for proteasome-dependent degradation of IRF-3 following viral infections or TLR3 engagement (Saitoh et al., 2006). Phosphorylation of IRF-3, especially at its Ser339 residue, appears to be a prerequisite for IRF-3 to be recognized by PIN1. However, PIN1 does not directly catalyze ubiquitination or subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation of its substrates, and its exact role in this process awaits further investigation. However, preliminary data argue against the involvement of PIN1 in Npro-mediated polyubiquitination of IRF-3. Firstly, PIN1 was not recruited to the IRF-3-Npro complex, regardless of the status of proteasome inhibition (Fig. 8C). Secondly, as mentioned above, Npro induced IRF-3 degradation in the absence of virus infection or dsRNA stimuli, when IRF-3 was not phosphorylated (Figs. 4A, 4B and 7C). Furthermore, although infection of MDBK cells with the cpBVDV strain NADL induced IRF-3 degradation, this was not the case with SeV infection (Figs. 1B and 4B). This suggests that BVDV and SeV are likely to utilize different mechanisms to target IRF-3 for degradation.

The ability of the HCV NS3/4A protease to disrupt IRF-3-dependent antiviral responses has been postulated to contribute to HCV persistence (Foy et al., 2003). Classified with in the same family Flaviviridae, both HCV and BVDV are able to cause persistent infections in their respective hosts. However, unlike HCV that frequently persists in adult humans, BVDV persistence is only established following infection of developing fetuses with ncp viruses (Brock, 2003; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003). The fact that both cpBVDV and ncpBVDV share similar mechanisms for ablating the expression of IRF-3 indicates that the disruption of IRF-3-dependent host defenses is not by itself sufficient for BVDV persistence. Nonetheless, such a mechanism could contribute to the increased frequency and severity of secondary infections in BVDV-infected animals (Fulton et al., 2000; Peterhans, Jungi, and Schweizer, 2003; Potgieter, 1997). Although it is not essential for either BVDV or CSFV replication (Lai et al., 2000; Tratschin et al., 1998), Npro has been retained during the evolution of all pestiviruses. It is also well-conserved among BVDV, CSFV, and BDV, sharing about 69% amino acid sequence homology. Interestingly, the Npro of CSFV was also shown very recently to target IRF-3 for proteasomal degradation (Bauhofer et al., 2007). Taken together, these facts suggest that Npro-mediated interference with IRF-3-dependent host defenses may play an important role in pestivirus pathogenesis. It remains to be demonstrated whether variations in the sequence of Npro contribute to altered pestivirus virulence in vivo, and whether the latter can be related to the ability of various Npros to interact with IRF-3 and/or other cellular protein partners required for targeting IRF-3 for polyubiquitination and proteasome-mediated destruction.

Materials and Methods

Cells and reagents

Human embryo kidney (HEK) 293, 293T, 293 cells stably expressing human TLR3 (293-TLR3, kindly provided by Kate Fitzgerald, University of Massachusetts), BOSC23 (kindly provided by Shinji Makino, University of Texas Medical Branch), HEC1B, and TH1 cells (Chen et al., 2007) (kindly provided by Robert Lanford, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research) were cultured by conventional techniques. MDBK cells (kindly provided by Ilya Frolov, University of Texas Medical Branch) were cultured similarly except that horse serum was used in place of fetal bovine serum. HeLa Tet-Off cells were maintained as indicated by the provider (Clontech). BALB/c 3T3-derived ts20 cells expressing a temperature-sensitive E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme (Chowdary et al., 1994) were kindly provided by Harvey L. Ozer (UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 35°C. Where indicated, cells were shifted to the restricted temperature (39°C) for 16h to inactivate the thermoliable E1. Stocks of cpBVDV NADL strain were kindly provided by Ilya Frolov, University of Texas Medical Branch, and had a titer of ~2X107 PFU/ml. The proteasome inhibitors, MG-115 and epoxomicin, were purchased from Sigma and Calbiochem, respectively. The pan-caspase inhibitor ZVAD-FMK was from R&D Systems.

Plasmids

Plasmids were generated by conventional PCR techniques. To construct a BVDV Npro expression vector, pcDNA6-Npro, cDNA encoding NADL strain Npro (which represents the first 168aa of the NADL polyprotein) was amplified by PCR from a plasmid containing a copy of the BVDV NADL genome (kindly provided by Ilya Frolov, University of Texas Medical Branch) and subsequently ligated into pcDNA6/V5-HisB (Invitrogen). To facilitate detection, we also constructed pcDNA6-mycNpro and pcDNA6-Npro-V5, in which the Npro fragment was placed in frame with an N-terminal c-myc tag or a C-terminal V5 tag, respectively. To generate the Npro-CAT fusion construct, cDNA encoding the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene was fused to the C-terminus of Npro cDNA and cloned into pBluescript. The junction between Npro and CAT contains a consensus Npro cis-cleavage site and 6 amino acid residues of BVDV capsid coding sequence, i.e., CPLWVTSC↓SDTKEE (Npro cleavage recognition sequence in bold face letters) (Rumenapf et al., 1998). The cDNA fragment encoding Npro-CAT was subsequently swapped into pcDNA6-mycNpro to generate pcDNA6-mycNpro-CAT. L8P, E22V, H49L, and C69A mutants of Npro or Npro-CAT were generated by QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) in the pcDNA6mycNpro and pcDNA6-mycNpro-CAT background, respectively. The Npro deletion mutants, N69, C99, N99, N130, and N144, were similarly generated in the pcDNA6-Npro-V5 background. To construct tet-regulated expression plasmids for wild-type (WT) and L8P mutant Npro, cDNA fragments encoding myc-tagged WT or L8P mutant Npro were cloned into pTRE2Bla (Chen et al., 2007). To generate retroviral expression constructs for WT and L8P mutant Npro, myc-Npro and myc-NproL8P cDNA fragments were excised from pTRE2Bla-mycNpro or pTRE2Bla-mycNproL8P, respectively, and ligated with a replication-incompetent retroviral expression vector, pCX4pur (a gift from Tsuyoshi Akagi, Osaka Bioscience Institute) (Akagi, Sasai, and Hanafusa, 2003).

Vectors expressing HCV NS3/4A, BVDV NS3/4A, human TRIF, RIG-I, and MAVS/IPS-1/Cardif/VISA have been described (Chen et al., 2007; Li et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005). pcDNA3-FlagTBK1 and pcDNA3-FlagIKKε (Fitzgerald et al., 2003) were kindly provided by Kate Fitzgerald (University of Massachusetts). pEF-Bos(+), pEF-Bos RIG-I and pEF-Bos N-RIG (Yoneyama et al., 2004) were gifts from Takashi Fujita (Kyoto University). The reporter plasmids pIFN-β-Luc (Lin et al., 1998), pISG56-Luc, PRDII-Luc(Fredericksen et al., 2002), and (PRDIII-I)4-Luc (Ehrhardt et al., 2004) were kindly provided by Rongtuan Lin (McGill University), Michael Gale (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), and Christina Ehrhardt (University of Wuerzburg), respectively. pIRF3(-779)-Luc containing human IRF-3 promoter upstream of firefly luciferase reporter gene was a gift from Paula Pitha-Rowe (Johns Hopkins University) (Lowther et al., 1999). The pGL3-Control plasmid that contains the SV40 promoter upstream of firefly luciferase gene was from Promega. pCMVβgal (Clontech) or pRL-TK (Promega) were used to normalize transfection efficiencies. Plasmid DNAs were transfected into cells using Fugene 6 (Roche) or TransIT-LT1 (Mirus) (for HEK293 and TH1 cells), or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, for HEC1B and HeLa cells), following the manufacturers’ instructions.

Establishment of HeLa cell lines with conditional expression of BVDV Npro

HeLa Tet-Off cells (Clontech) were transfected with pTRE2Bla-mycNpro or pTRE2Bla-mycNproL8P and double-selected in complete medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml G418, 1 μg/ml blasticidin and 2 μg/ml tetracycline. Three weeks later, individual cell colonies were selected, expanded, and examined for Npro expression by indirect immunofluorescence staining and immunoblot analysis with a monoclonal antibody against c-myc tag (Cell Signaling Tech) after being cultured in the absence of tet for 4 days. Cell clones that allowed tight regulation of WT or L8P mutant Npro expression by tetracycline were selected for further characterization. Two WT Npro-inducible clones, designated Npro-25 and Npro-29, and three L8P mutant cell lines, designated L8P-1, L8P-22 and L8P-38, respectively, were used in this study.

Generation of MDBK and ts20 cells with stable expression of Npro, L8P mutant Npro, or control vector

Replication-incompetent retroviruses encoding WT or L8P mutant Npro, or the empty vector were harvested from supernatants of BOSC23 cells cotransfected with pCL-10A1 (a gift from Tianyi Wang, University of Pittsburgh) and pCX4pur-derived vectors encoding myc-tagged, WT or L8P mutant Npro, or pCX4pur, respectively. The retroviruses were subsequently used to transduce MDBK and ts20 cells in the presence of 8μg/ml of polybrene (Sigma). Following selection with puromycin for ~2 weeks, survived cell colonies were pooled and used as a stable population for further analysis.

Poly (I-C) treatment and Sendai virus (SeV) infection

Where indicated, cells were incubated with 50 μg/ml of poly (I-C) (Sigma) in culture medium for 8 ~15h, or infected with 100 hemagglutinin units (HAU)/ml of SeV (Cantell strain, Charles River Laboratories) for 16 hrs prior to cell lysis for luciferase/β-gal reporter assays and/or immunoprecipitation /immunoblot analysis as previously described (Foy et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005).

Reporter gene assay

Cells (5 X 104 to 105 cells per well in 24 well plates) were transfected with reporter plasmids (100 ng), pCMVβgal (100 ng) and the indicated amount of an expression vector. Where indicated, cells were mock treated, or incubated with poly (I-C), or challenged with SeV at 24h posttranfection, and subsequently lysed and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. For comparisons, luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. In some experiments renilla luciferase was used as an internal control and a dual-luciferase assay was performed to calculate relative luciferase activity. Data are expressed as mean relative luciferase activity plus standard deviation for one representative experiment carried out in triplicate, typically from a minimum of three separate experiments. The fold-induction of promoter activity was calculated by dividing the relative luciferase activity of stimulated cells by that of mock-treated cells.

Indirect Immunofluorescence staining

Cells grown in 4-well or 8-well chamber slides were fixed and permeabilized, and subsequently immunostained with anti-c-myc-tag antibody (Cell Signaling Tech, for detection of myc-tagged Npro) and/or IRF-3 antisera (Navarro and David, 1999) (a gift from Michael David, University of California-San Diego) as previously described (Foy et al., 2003; Li et al., 2002). Cells were examined under a Zeiss Axioplan II fluorescence microscope or an LSM-510 META laser scanning confocal microscope in the UTMB Optimal Imaging Core.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblots

Cellular extracts were prepared, quantified, and subjected to immunoprecipitation and/or immunoblot analysis as previous described (Foy et al., 2003; Li et al., 2005). The following monoclonal (mAb) or polyclonal (pAb) antibodies were used: anti-c-myc tag mAb and rabbit anti-PIN1 pAb (Cell Signaling Tech); anti-CAT pAb and anti-FLAG M2 and anti-actin mAbs (Sigma); anti-V5 mAb (Invitrogen); rabbit anti-BVDV NS3 pAb (a gift from Charles Rice, Rockefeller University); rabbit anti-IRF-3 pAb (a gift from Michael David, University of California-San Diego); anti-CBP pAb and anti-IRF-3 and anti-ubiquitin mAbs (Santa Cruz); rabbit anti-ISG56 pAb (a gift from Ganes Sen, Cleveland Clinic); rabbit anti-ISG15 pAb (a gift from Arthur Haas, Medical College of Wisconsin); rabbit anti-MxA and anti-Sendai virus pAbs (gifts from Ilkka Julkunen, National Public Health Institute, Helsinki); and peroxidase-conjugated secondary anti-rabbit and anti-mouse pAbs (Southern Biotech). Protein bands were visualized using ECL Plus Western Blotting detection reagents (GE HealthCare), followed by exposure to X-ray film.

Northern Blots

Total cellular RNA was isolated using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and subjected to Northern blot analysis by using specific anti-sense riboprobes as per manufacturer’s protocol (NorthernMax Kit, Ambion). Briefly, 15–20 μg of total RNA was fractionated on denaturing formaldehyde agarose (0.9%) gels followed by capillary transfer to BrightStar-Plus Nylon membrane (Ambion). Following UV cross-linking, membranes were hybridized with 32P-labled antisense riboprobes specific to human ISG56, human IRF3, BVDV Npro, bovine IRF3 and bovine ISG15 that were prepared by Maxiscript T7 kit (Ambion) at 68ºC overnight. Subsequently, membranes were extensively washed and autoradiographed or scanned with a Phosphor-Imager (Molecular Dynamics). Ethidium bromide staining of 28S and 18S rRNA was used as loading controls.

Quantitative real-time PCR

mRNAs for human IFN-β, IRF-3, and 18S rRNA were quantified in total cellular RNA extracts using commercially available primers and TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems) by RT-PCR at the UTMB Sealy Center for Cancer Biology Real Time PCR Core. The relative abundance of each target was obtained by normalization with endogenous 18S RNA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01-AI069285 and R21-DA018054 (to K.L.), U19-AI40035 (to S.M.L.), and the John Mitchell Hemophilia of Georgia Liver Scholar Award from the American Liver Foundation (to K.L.). K.L. is a Cain Foundation Investigator in Innate Immunity. We are grateful to Ilya Frolov for kindly providing the BVDV NADL viral stocks, MDBK cells, and NADL cDNA clone used in this study. We thank Takashi Fujita, Kate Fitzgerald, Michael Gale, Paula Pitha-Rowe, Rongtuan Lin, Tsuyoshi Akagi, Tianyi Wang, and Christina Ehrhardt for providing plasmids; Harvey L. Ozer, Shinji Makino, and Robert Lanford for providing cell lines, Charles Rice, Ilkka Julkunen, Michael David, Arthur Haas, and Ganes Sen for providing antibodies. We are grateful to the UTMB Sealy Center for Cancer Biology Real Time PCR core for assistance with real-time RT-PCR assays and the UTMB Optimal Imaging Core for assistance with fluorescence microscopy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akagi T, Sasai K, Hanafusa H. Refractory nature of normal human diploid fibroblasts with respect to oncogene-mediated transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(23):13567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834876100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baigent SJ, Zhang G, Fray MD, Flick-Smith H, Goodbourn S, McCauley JW. Inhibition of beta interferon transcription by noncytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhea virus is through an interferon regulatory factor 3-dependent mechanism. J Virol. 2002;76 (18):8979–88. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.18.8979-8988.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barro M, Patton JT. Rotavirus nonstructural protein 1 subverts innate immune response by inducing degradation of IFN regulatory factor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(11):4114–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408376102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauhofer O, Summerfield A, Sakoda Y, Tratschin JD, Hofmann MA, Ruggli N. Classical swine fever virus Npro interacts with interferon regulatory factor 3 and induces its proteasomal degradation. J Virol. 2007;81(7):3087–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02032-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibeau-Poirier A, Gravel SP, Clement JF, Rolland S, Rodier G, Coulombe P, Hiscott J, Grandvaux N, Meloche S, Servant MJ. Involvement of the IkappaB kinase (IKK)-related kinases tank-binding kinase 1/IKKi and cullin-based ubiquitin ligases in IFN regulatory factor-3 degradation. J Immunol. 2006;177(8):5059–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury LS, Carr BV, Charleston B. Aspects of the innate and adaptive immune responses to acute infections with BVDV. Vet Microbiol. 2003;96(4):337–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock KV. The persistence of bovine viral diarrhea virus. Biologicals. 2003;31(2):133–5. doi: 10.1016/s1045-1056(03)00029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charleston B, Fray MD, Baigent S, Carr BV, Morrison WI. Establishment of persistent infection with non-cytopathic bovine viral diarrhoea virus in cattle is associated with a failure to induce type I interferon. J Gen Virol. 2001;82(Pt 8):1893–7. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-8-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Gerlier D. Viral hijacking of cellular ubiquitination pathways as an anti-innate immunity strategy. Viral Immunol. 2006;19(3):349–62. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Benureau Y, Rijnbrand R, Yi J, Wang T, Warter L, Lanford RE, Weinman SA, Lemon SM, Martin A, Li K. GB Virus B Disrupts RIG-I Signaling by NS3/4A-Mediated Cleavage of the Adaptor Protein MAVS. J Virol. 2007;81(2):964–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02076-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdary DR, Dermody JJ, Jha KK, Ozer HL. Accumulation of p53 in a mutant cell line defective in the ubiquitin pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(3):1997–2003. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Noyce RS, Mossman KL. Innate cellular response to virus particle entry requires IRF3 but not virus replication. J Virol. 2004;78(4):1706–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1706-1717.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt C, Kardinal C, Wurzer WJ, Wolff T, von Eichel-Streiber C, Pleschka S, Planz O, Ludwig S. Rac1 and PAK1 are upstream of IKK-epsilon and TBK-1 in the viral activation of interferon regulatory factor-3. FEBS Lett. 2004;567(2–3):230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, Coyle AJ, Liao SM, Maniatis T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(5):491–6. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy E, Li K, Sumpter R, Jr, Loo YM, Johnson CL, Wang C, Fish PM, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Lemon SM, Gale M., Jr Control of antiviral defenses through hepatitis C virus disruption of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(8):2986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408707102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foy E, Li K, Wang C, Sumpter R, Jr, Ikeda M, Lemon SM, Gale M., Jr Regulation of interferon regulatory factor-3 by the hepatitis C virus serine protease. Science. 2003;300(5622):1145–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1082604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen B, Akkaraju GR, Foy E, Wang C, Pflugheber J, Chen ZJ, Gale M., Jr Activation of the interferon-beta promoter during hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Viral Immunol. 2002;15(1):29–40. doi: 10.1089/088282402317340215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton RW, Purdy CW, Confer AW, Saliki JT, Loan RW, Briggs RE, Burge LJ. Bovine viral diarrhea viral infections in feeder calves with respiratory disease: interactions with Pasteurella spp., parainfluenza-3 virus, and bovine respiratory syncytial virus. Can J Vet Res. 2000;64(3):151–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil LH, Ansari IH, Vassilev V, Liang D, Lai VC, Zhong W, Hong Z, Dubovi EJ, Donis RO. The amino-terminal domain of bovine viral diarrhea virus Npro protein is necessary for alpha/beta interferon antagonism. J Virol. 2006;80(2):900–11. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.900-911.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutagny N, Severa M, Fitzgerald KA. Pin-ning down immune responses to RNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):555–7. doi: 10.1038/ni0606-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton L, Moganeradj K, Zhang G, Chen YH, Randall RE, McCauley JW, Goodbourn S. The NPro product of bovine viral diarrhea virus inhibits DNA binding by interferon regulatory factor 3 and targets it for proteasomal degradation. J Virol. 2006;80(23):11723–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01145-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horscroft N, Bellows D, Ansari I, Lai VC, Dempsey S, Liang D, Donis R, Zhong W, Hong Z. Establishment of a subgenomic replicon for bovine viral diarrhea virus in Huh-7 cells and modulation of interferon-regulated factor 3-mediated antiviral response. J Virol. 2005;79(5):2788–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2788-2796.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huibregtse JM, Scheffner M, Howley PM. Cloning and expression of the cDNA for E6-AP, a protein that mediates the interaction of the human papillomavirus E6 oncoprotein with p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(2):775–84. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ, Yamaguchi O, Otsu K, Tsujimura T, Koh CS, Reis ESC, Matsuura Y, Fujita T, Akira S. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006 doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Antiviral signaling through pattern recognition receptors. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2006 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(2):131–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Takahashi K, Sato S, Coban C, Kumar H, Kato H, Ishii KJ, Takeuchi O, Akira S. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol. 2005 doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rocca SA, Herbert RJ, Crooke H, Drew TW, Wileman TE, Powell PP. Loss of interferon regulatory factor 3 in cells infected with classical swine fever virus involves the N-terminal protease, Npro. J Virol. 2005;79(11):7239–47. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7239-7247.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner T, Muller A, Pankraz A, Becher P, Thiel HJ, Gorbalenya AE, Tautz N. Temporal modulation of an autoprotease is crucial for replication and pathogenicity of an RNA virus. J Virol. 2004;78(19):10765–75. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10765-10775.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai VC, Zhong W, Skelton A, Ingravallo P, Vassilev V, Donis RO, Hong Z, Lau JY. Generation and characterization of a hepatitis C virus NS3 protease-dependent bovine viral diarrhea virus. J Virol. 2000;74(14):6339–47. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6339-6347.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]