Abstract

How eukaryotic genomes encode the folding of DNA into nucleosomes and how this intrinsic organization of chromatin guides biological function are questions of wide interest. The physical basis of nucleosome positioning lies in the sequence-dependent propensity of DNA to adopt the tightly bent configuration imposed by the binding of the histone proteins. Traditionally, only DNA bending and twisting deformations are considered, while the effects of the lateral displacements of adjacent base pairs are neglected. We demonstrate, however, that these displacements play a much more important structural role than ever imagined. Specifically, the lateral Slide deformations observed at sites of local anisotropic bending of DNA define its superhelical trajectory in chromatin. Furthermore, the computed cost of deforming DNA on the nucleosome is sequence specific: in optimally positioned sequences the most easily deformed base-pair steps (CA:TG and TA) occur at sites of large positive Slide and negative Roll (where the DNA bends into the minor groove). These conclusions rest upon a treatment of DNA that goes beyond the conventional ribbon model, incorporating all essential degrees of freedom of ‘real’ duplexes in the estimation of DNA deformation energies. Indeed, only after lateral Slide displacements are considered, are we able to account for the sequence-specific folding of DNA found in nucleosome structures. The close correspondence between the predicted and observed nucleosome locations demonstrates the potential advantage of our 'structural' approach in the computer mapping of nucleosome positioning.

Keywords: base-pair shearing, DNA deformation, knowledge-based potentials, nucleosome positioning, superhelical pitch

INTRODUCTION

The tight, superhelical wrapping of nucleosomal DNA around the core of histone proteins introduces significant deformation in the double-helical structure.1 The enhanced binding of the histone assembly to specific DNA ‘positioning’ sequences,2-4 essentially in the absence of direct sequence-specific interactions with bases,5-9 points to an indirect mechanism of molecular recognition involving the intrinsic structure and/or deformability of nucleotide steps.

Analyses of DNA structure in the nucleosome core particle1,10,11 typically focus on the local angular parameters (Roll, Tilt, Twist) that describe the bending and twisting of adjacent base pairs.12 Nucleosomal DNA bends anisotropically, with the Roll angle (bending into the grooves) being appreciably greater than Tilt (bending toward the backbone).1,13 The double helix also tends to underwind at sites of major-groove bending and to overwind at sites of minor-groove bending,5,14 so that the average twisting of base pairs on nucleosomal DNA is comparable to that of naked DNA, i.e., ∼10.4 bp/turn.1

Thus, within the limits of the conventional ribbon model of DNA, the folding of the double helix on the nucleosome is described in terms of the principal angular variables, Roll and Twist. Even though the ‘real’ bending of DNA on the nucleosome occurs in concert with the in-plane dislocation of base pairs (Supplementary Fig. S1), these deformations, so-called Shift and Slide, are usually ignored. The former parameter is thought to facilitate the tight packing of nucleosomal DNA against protein, while the effect of Slide on the overall trajectory of nucleosomal DNA has not been considered.1,8

Here we take a fresh approach, focusing on the irregularities of DNA at the level of dimeric steps and comparing the contributions of the aforementioned angular and translational parameters to the observed fold of nucleosomal DNA. Unexpectedly, we find that the variation of Slide, i.e., the shear displacements of adjacent base pairs along their long axes, across the DNA grooves, controls the DNA superhelical pitch. This observation clearly goes beyond the limits of the ribbon model, adding a new dimension to the current paradigm.

We subsequently investigate the mechanisms by which ‘local’ Slide and Roll control the superhelicity and ‘global’ curvature of nucleosomal DNA and the underlying base-sequence-dependent contributions of these parameters to the deformation ‘energy’ of the protein-bound duplex. We estimate the cost of deforming the DNA on the observed, high-resolution core- particle structure8 with knowledge-based elastic functions15 that reflect the sequence-dependent conformational properties of DNA in other structural contexts. This novel approach incorporates all the essential degrees of freedom of ‘real’ DNA structures and helps to decipher the contribution of DNA sequence-dependent deformability to the positioning of nucleosomes. The computed scores of representative sequences that are ‘threaded’ on the crystalline template account remarkably well for the reported dyad sites of some of the best-resolved nucleosome-positioning sequences.

RESULTS

A different perspective on nucleosomal DNA

Examination of nucleosomal DNA from the conventional viewpoint down its superhelical axis (Fig. 1a) reveals the sharp, localized bends, or mini-kinks, responsible for the tight wrapping of the double helix around the core of histone proteins. These well-known bending sites, highlighted here by color coding that denotes the direction of the strongest dimeric bends, occur at regularly spaced (5−6 bp) intervals and alternately compress the major and minor grooves on the side of DNA that faces the protein core.

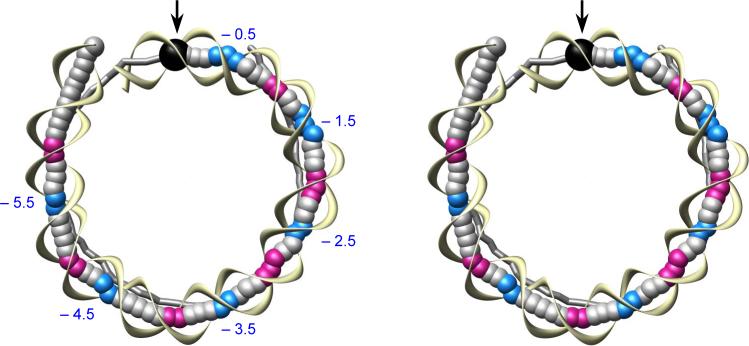

Figure 1.

Superhelical path of nucleosomal DNA. (a) Conventional (stereo) view down the superhelical axis. (b) Side view, obtained from (a) by ∼60° rotation around the vertical axis. Base-pair centers along one half of the nucleosome core particle are represented by large balls and the intervening sugar-phosphate backbone by yellow ribbons. The other half of the DNA is depicted by a gray tube, which connects successive base-pair centers. Sites of major-groove bending (negative Slide) are highlighted in red and sites of minor-groove bending (positive Slide) in blue. Superhelical locations (from –0.5 to –5.5) are denoted, following Luger et al.,5 by the number of helical turns away from the dyad passing through the central base pair (depicted by a black ball and highlighted by arrows). The superhelical axis of DNA, shown by a fine red line, minimizes the sum ∑(dn − 〈d〉)2, where 〈d〉 is the average of dn , the distance from the n-th base-pair center to the line, for n = 1 to 147 . Base-pair centers obtained from 3DNA17 and molecular images prepared with the Chimera software package.50

Other complexities in the DNA trajectory become apparent if the nucleosomal structure is viewed from a different perspective. A side view (Fig. 1b) reveals abrupt displacements of the DNA spatial trajectory — see, for example, positions –5.5 and –1.5. The dislocations of the helical axis are easily seen if the molecule is reduced, as here, to a single point per base pair and viewed in the absence of protein. Note that these ‘axial dislocations’ are located at the color-coded points and thus, are associated with the strongest bends.

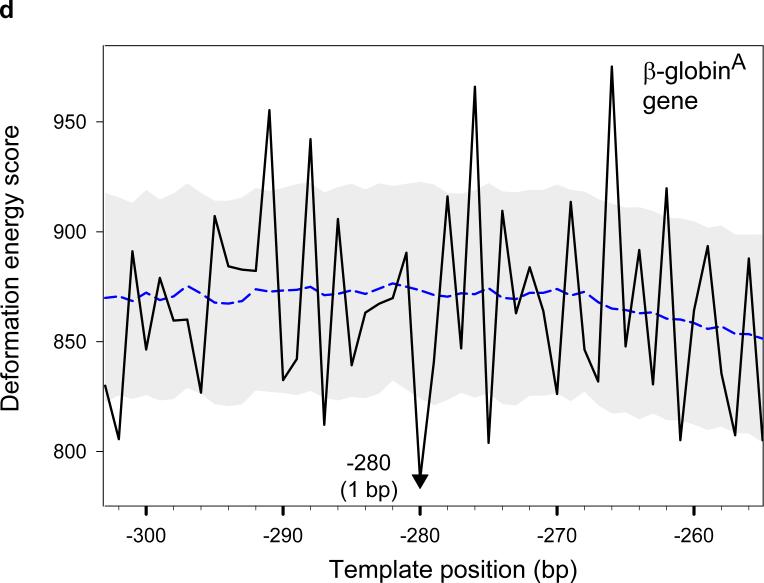

The bending of DNA via Roll is well known to occur in concert with the displacement of base pairs via Slide and changes in dimeric Twist. In this regard, the deformations of DNA on the nucleosome (Supplementary Fig. S1) are similar to those in complexes with other proteins.15 The uniqueness of the nucleosomal structure lies in the magnitude of Slide: the sites of strongest DNA bending into the minor groove (negative Roll) are accompanied by the shearing of successive base pairs via large positive Slide, i.e., values of ∼2.5 Å computed with the CompDNA/3DNA software packages16,17 (Fig. 2a, b). The sliding of base pairs is less pronounced when DNA is bent into the major groove; nevertheless, the ‘axial dislocation’ is quite noticeable (Slide ≈ – 1 Å, see Fig. 2c, d). Given the influence of Slide on DNA helical-axis dislocations at the level of several base pairs, one immediately wonders what, if any, role Slide might play in the overall structure of nucleosomal DNA.

Figure 2.

Detailed atomic-level representations of nucleosomal DNA fragments containing steps with large positive and negative Slide. Views on the left highlight the dislocation of the local helical axis and those on the right the accompanying bends into the minor and major grooves. (a, b) Minor-groove CA:TG bend with positive Slide, step −36. (c, d) Major-groove TA:TA bend with negative Slide, step −51. The color scheme is the same as in Fig. 1: minor-groove bending is highlighted in blue and major-groove bending in red. Local helical axes minimize the displacements of the three base-pair centers on either side of the deformation site. Base-pair positions are measured relative to the dyad located at 0.

Contributions of individual ‘step’ parameters to nucleosomal structure

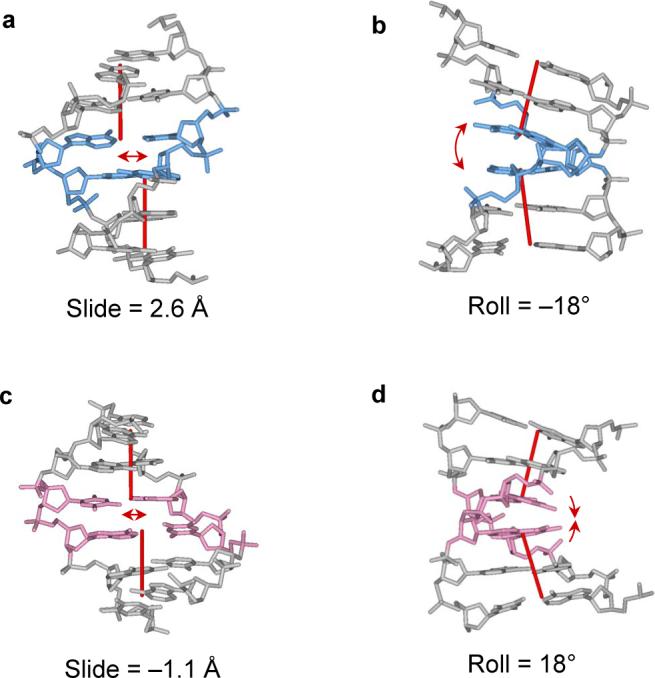

In order to understand the effects of local deformations of double-helical structure on the global folding of nucleosomal DNA, we constructed a series of models in which the value of one of the base-pair step parameters is equated to zero at all dinucleotide steps (Fig. 3). Such models pinpoint the types of local conformational change responsible for the left-handed, superhelical pathway of nucleosomal DNA. The assumed distortions direct the protein-bound duplex toward the canonical B-DNA structure where there is neither bending, i.e., Tilt = Roll = 0°, nor shearing, i.e., Shift = Slide = 0 Å, of local base-pair steps.

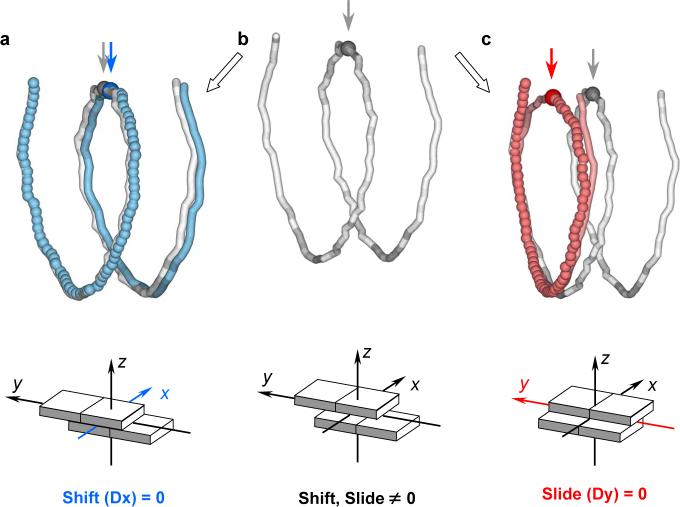

Figure 3.

Effect of ‘zeroing’ dinucleotide step parameters (a, Shift; c, Slide) on the superhelical path of DNA in the nucleosome core particle8 (b). The modified DNA trajectories are represented, as in Fig. 1, by large balls and tubes connecting successive base-pair centers; the dyad positions are highlighted by darkened balls and indicated by arrows. The DNA models are superimposed at the initial base pair of the observed nucleosomal DNA structure (white tubes in (a, c) have the same configuration as in (b)). The ‘far’ ends of the DNA model and the core-particle structure are separated by ∼5 Å in (a) and ∼30 Å in (c). Model structures are built from the 3DNA17 structural parameters of nucleosomal DNA, with the parameter of interest equated to zero at each dinucleotide step. Lower ‘block’ images illustrate the Slide-Shift ‘zeroing’ scheme at the level of successive base pairs. Arrows here denote the coordinate frame embedded in each base pair.

For example, setting the value of Roll to zero at all base-pair steps almost completely straightens the DNA, whereas setting the values of Tilt to zero has only a modest effect on the DNA trajectory (Supplementary Fig. S2). In other words, variation in Roll (but not in Tilt) accounts for most of the bending of DNA on the nucleosome, a result consistent with well-known ideas of DNA bending anisotropy.13,18

The influence of the shear parameters, Shift and Slide, on the global fold of nucleosomal DNA is unexpected (Fig. 3). Whereas freezing the Shift to canonical values, i.e., zero, at all base-pair steps (Fig. 3a) has almost no effect on the DNA spatial pathway, setting the values of Slide to zero (Fig. 3c) nearly flattens the DNA trajectory. Notably, the composite changes in Slide diminish the pitch of nucleosomal DNA from ∼30 Å per superhelical turn (∼80 bp) in the native structure to 3 Å in the Slide-frozen model.

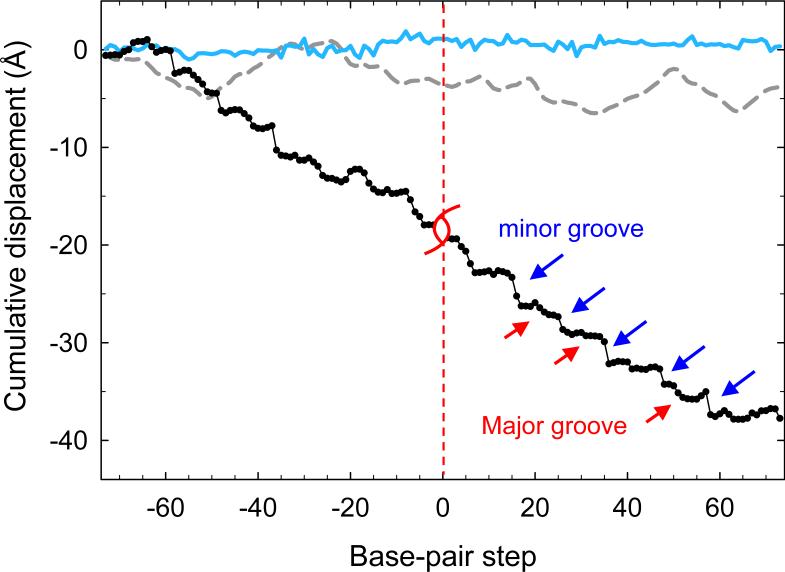

The cumulative contributions to overall nucleosomal pitch, i.e., the net displacement of histone-bound DNA along the superhelical axis, from the two shear parameters as well as that from Rise, the vertical displacement of neighboring base-pair planes,12 are reported in Figure 4. The plotted data are the projections, at each dinucleotide step, of the three components of base-pair displacement on the superhelical axis (dotted red line in Fig. 1b). It should be noted that if DNA behaved as an ideal ribbon,19-21 the superhelical pitch would be defined entirely by the projection of the base-pair Rise on the superhelical axis (because the ribbon model ignores the shearing of base-pair planes). Our analysis shows, however, that Rise accounts for less than 10% of the pitch (Fig. 4); the impact of Shift is even smaller. By contrast, Slide accounts for over 90% of the overall pitch of nucleosomal DNA, with positive Slide making a greater contribution than negative Slide (see Fig. 2 and below). The data further reveal a stepwise accumulation of net pitch. There is a sizable build-up of pitch at ∼10-bp increments along the DNA sequence (blue arrows in Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Cumulative effects of local base-pair translation on the overall pitch of nucleosomal DNA. Contributions of Slide, Shift, and Rise are shown by black, cyan, and gray lines, respectively. Base-pair displacements are measured along the global axis of the core-particle structure (red line in Fig. 1b). Base-pair positions are defined with respect to the dyad, which is at 0. Red and blue arrows denote stepwise displacements associated respectively with major- and minor-groove bends.

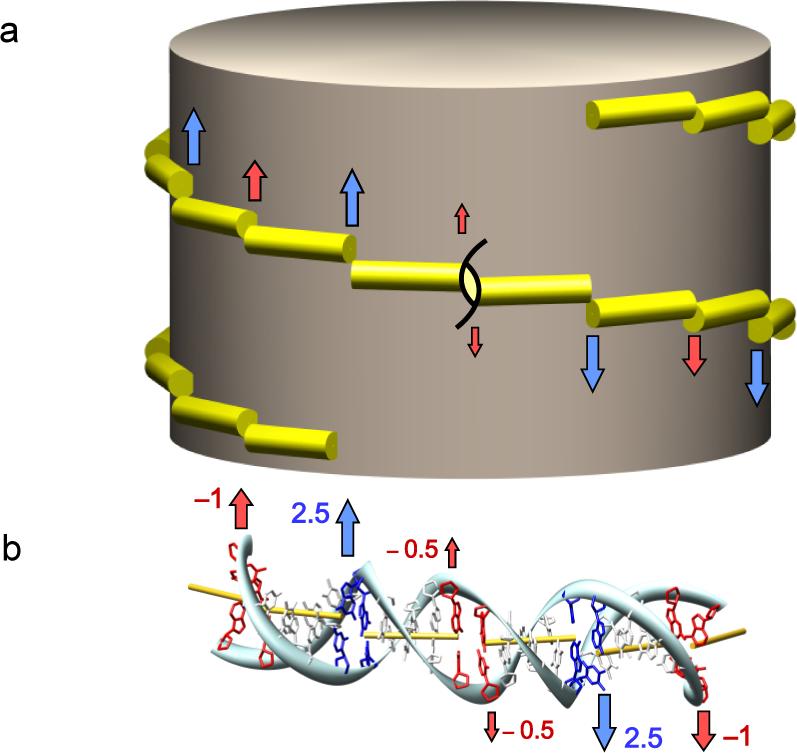

Mechanism of controlling nucleosomal pitch via Slide

The mechanism by which Slide controls nucleosomal pitch is outlined in Figure 5. Sharp jumps in Slide occur at regular intervals along the DNA (Fig. 5a). The positive values of Slide accompany DNA bending into the minor groove (negative values of Roll, blue arrows) and the negative values appear with DNA bending into the major groove (positive values of Roll, red arrows); compare with Fig. 2. Because the direction of Slide is roughly parallel to the superhelical axis at the sites of Roll deformation, the values of Slide accumulate along the path of nucleosomal DNA. Moreover, steps with alternating positive and negative Slide (separated by 5−6 bp) contribute cooperatively to the overall pitch. A distance of 5−6 bp along the DNA double helix is equivalent to ∼180° of net twisting. Thus, the negative Slide at sites where the DNA bends into the major groove and the positive Slide at sites where the DNA bends into the minor groove run parallel to the global superhelical axis (Fig. 5b) and add cumulatively to the pitch (Fig. 4). The negative (rather than positive) correlation between Slide and Roll, i.e., the decrease of Roll that accompanies the increase of Slide and vice versa, determines the left-handedness of the DNA superhelix.14

Figure 5.

Idealized representation of the superhelical pathway of nucleosomal DNA. (a) The DNA path is shown as a left-handed spiral staircase with each ‘step’ spanning a 5-bp DNA fragment. Red and blue arrows indicate displacements in Slide associated respectively with major- and minor-groove bends. (b) Atomic-level view of an idealized double helix with parameters close to those shown in Fig. 2: the DNA alternatively bends, every 5 bp, by 22.5° into the minor and major groove. Values of (Slide, Twist) are set to (2.5 Å, 41°) at minor-groove bends (blue arrows), (–1 Å, 31°) at major-groove bends (red arrows), and (0 Å, 36°) elsewhere. The yellow rods represent the local helical axes. Note the uniform direction of helical-axis displacement in both images, i.e., along the global axis of the nucleosome. Also notice that, since the shear displacements do not alter the bending and twisting of successive nucleotides, the base pairs retain the same orientation, regardless of the degree of superhelical pitch. The twisting of DNA along the three-dimensional superhelical pathway, as defined in 3DNA,17 is accordingly the same as that of a double helix kinked into a planar circle by same pattern of bending but without accompanying variation in Slide.

As is clear from the figure, DNA wraps on the surface of the nucleosome core particle via a ‘staircase’ rather than a ‘ramp’ mechanism. That is, the double helix retains fragments of naturally straight, B-type duplex separated by sharp turns/dislocations in three-dimensional structure, i.e., ∼5-bp ‘treads’ joined by dimeric ‘risers’. This differs from the classical representation of nucleosomal DNA as a smoothly deformed superhelix with uniform dinucleotide bending and constant build-up of pitch.

The net positive Slide, associated with DNA bending into the minor groove, exceeds the net negative Slide by more than two-fold. Moreover, the deformation of DNA via positive Slide is much more extreme (with higher numerical values) in the nucleosome than in most other high-resolution protein-DNA crystal complexes.15 Accordingly, positive ‘minor-groove’ Slide makes the major contribution to the overall pitch of nucleosomal DNA (27 Å of 38 Å). In this regard DNA bending and sliding are different: whereas most DNA curvature accumulates at sites where DNA bends into the major groove, most of the contribution to pitch occurs at sites where DNA bends into the minor groove.

Sequence-dependent deformations of nucleosomal DNA

The examples of large positive Slide that accompany the sharp minor-groove kinking of nucleosomal DNA occur almost exclusively at CA:TG steps in the known core-particle structures, e.g., steps ±58, ±48, ±36 relative to the dyad in the best-resolved structure with 147 bp DNA8 (see Supplementary Table S1 for the locations and composition of the most highly deformed dimer steps in all currently solved mononucleosome structures). Furthermore, the CA:TG dimer assumes ‘kink-and-slide’ conformational states, like those in Fig. 2, in many other protein-DNA complexes15 (see Supplementary Table S2).

The broad range of pyrimidine-purine conformational states in other protein-bound structures15 leads one to expect that TA and CG steps might also accommodate the ‘kink-and-slide’ conformation observed in the nucleosome. These expectations are confirmed, however, in only one of these two dimers. Although not found at severely deformed steps in currently available high-resolution nucleosome core-particle structures, there are numerous examples of TA dimers that adopt ‘kink-and-slide’ combinations of large positive Slide and negative Roll in the presence of other proteins15 (Supplementary Table S2). By contrast, the CG dimer shows no such conformational propensities in complexes with other proteins (there is only a single example in the table). Moreover, none of the purine-purine and purine-pyrimidine sequences is predisposed to adopt the ‘kink-and-slide’ arrangements found in nucleosomes.

Analysis of the DNA stiffness constants associated with deformations of the double helix in known protein-DNA complexes15 clarifies why CA:TG and TA dimers are particularly suited to take up the minor-groove kinks found in the nucleosome. These dimers are not only highly flexible but also characterized by negative ‘Roll-Slide’ correlations (see Fig. 4 in ref. 15 and Supplementary Fig. S3). This correlation leads to an increase in Slide when Roll becomes more negative; in other words, the ‘kink-and-slide’ configuration is inherent to these dimers. (The CA:TG dimer is also subject to positive ‘Twist-Slide’ correlations that facilitate the over-twisting of DNA found at ‘kink-and-slide’ states in the nucleosome; see below.)

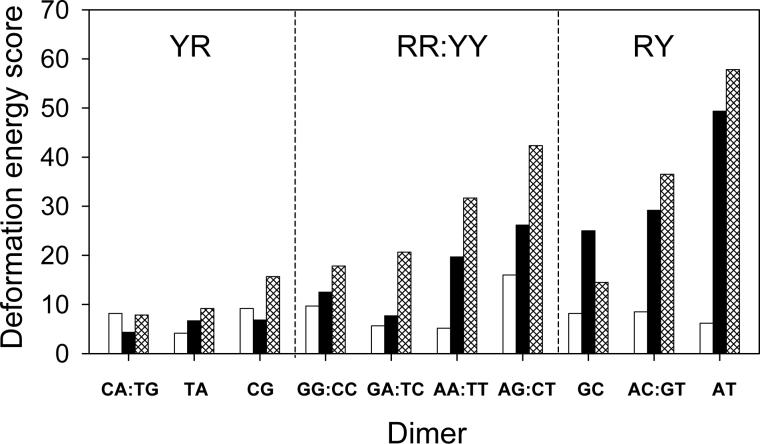

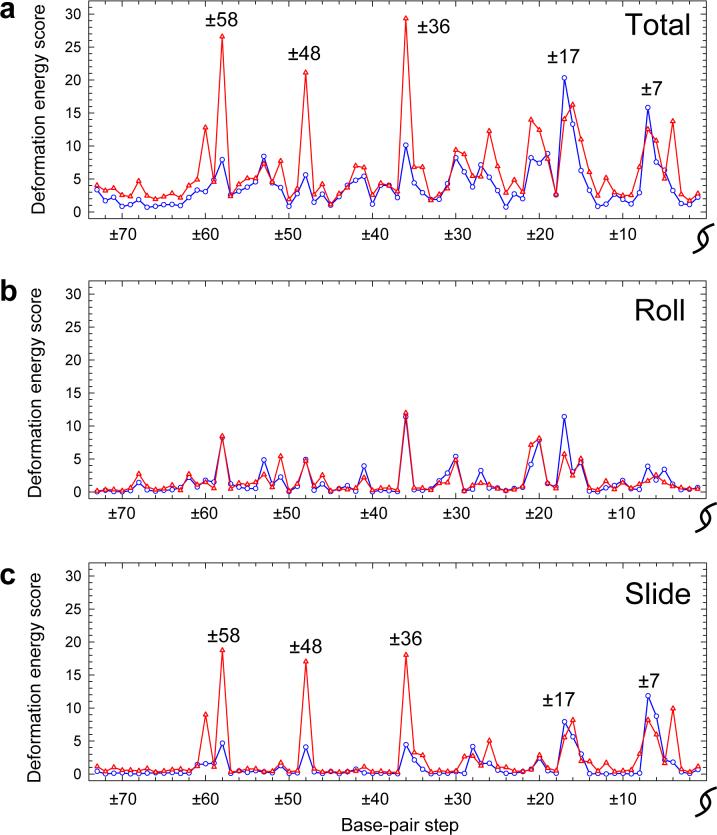

The cost of ‘kink-and-slide’ distortions of nucleosomal DNA, estimated on the basis of the sequence-dependent spread of conformational states in other protein-DNA complexes, is thus much lower for CA:TG and TA steps than for all other dimers (Fig. 6). The computed ‘energies’ in the figure are statistical scores that measure the cost of deforming a particular DNA base-pair step relative to the observed dispersion of step parameters of the same type of dimer in many other structural contexts; see ref. 15 and below for details of the knowledge-based potentials. Here we show the deformation scores of the 10 unique dimers, averaged over all six ‘kink-and-slide’ states in the best-resolved nucleosome structure,8 and the contributions to the total from the distortions of Slide and Roll. As is clear from the figure, the high cost of large positive Slide constitutes most of the total score. Indeed, in the case of GC steps the Slide contribution even exceeds the total score. (The favorable coupling of selected base-pair parameters introduces negative ‘cross’ terms in the total energy, thereby lowering the total ‘energy’ of steps like GC and CA:TG or TA.) Furthermore, whereas the total deformation scores vary six-fold over the different steps, the contribution from Slide varies about ten-fold in the different dimers and the contribution from Roll by only four-fold (Supplementary Table S3). Thus the changes in Slide, which are so critical to the overall folding of nucleosomal DNA, are clearly dependent on sequence and are potentially useful in the positioning of arbitrary DNA sequences on the nucleosome.

Figure 6.

Histograms illustrating the deformation ‘energy’ required for each of the 10 unique base-pair steps to adopt the ‘kink-and-slide’ configuration. The ‘energies’, computed according to Eqn. 1, are (unitless) statistical scores that measure the imposed deformation of individual base-pair steps on the nucleosome relative to the observed dispersion of the corresponding step parameters in other structural contexts.15 Reported values are averaged over the six ‘kink-and-slide’ steps, found at positions ±58, ±48, ±36 with respect to the observed dyad.8 The total ‘energy’ (hatched columns) is shown together with the contributions from Roll (white columns) and Slide (black columns); see Methods and legend to Table 1 for details.

Implications for nucleosome positioning

The ‘threading’ scores in Table 1 provide information on the relative ease of deforming different DNA sequences on the surface of the nucleosome core particle. The score for each sequence is the sum of the elastic contributions associated with the deformation of base-pair steps along the entire nucleosomal pathway (Fig 7). In other words, the DNA sequences are constrained to adopt the folding pattern found in the crystal structure (Fig. 1) and the ‘energy’ required to distort the sequence in this pattern is assessed with the scoring functions used above. The sequences include the human α-satellite DNA incorporated in the best-resolved core-particle structure and a ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA with ‘energy’ equal to the average deformation score, evaluated over all 16 dinucleotides, at each base-pair step of the template.15

Table 1.

Contributions of dinucleotide step parameters and the total scores of representative 147-bp sequences `threaded' on the nucleosome core-particle structure8*

| DNA sequence | Twist | Tilt | Roll# | Shift | Slide# | Rise | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human α-satellite† | 94.6 | 105.2 | 240.4 | 112.5 | 166.5 | 95.4 | 586.0 |

| Mixed-sequence§ | 150.2 | 115.3 | 241.2 | 124.0 | 325.0 | 100.7 | 911.5 |

DNA sequence co-crystallized with the histone octamer in the best-resolved nucleosome core-particle structure8.

Hypothetical DNA sequence with `energy' equal to the average deformation scores calculated for all 16 dimers at each of the base-pair steps of the template.

Note that the Roll and Slide terms are the largest for both sequences.

Figure 7.

Deformation ‘energy’ profiles of a ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA (red lines) and the human α-satellite sequence (blue lines) ‘threaded’ on the core-particle structure.8 Base-pair steps are indicated by their distance from the dyad (denoted by the standard symbol at 0). (a) Total score; (b, c) contributions of Roll and Slide components, respectively (see legend to Table 1). The scores at each position are averaged over two dimeric conformations: (i) the value associated with the given base-pair step and (ii) that of its symmetrical counterpart. The sites of minor-groove bending, which produce major peaks in the deformation ‘energy’ score, are highlighted by their numerical locations.

The threading of the α-satellite sequence on its ‘natural’ template is appreciably less costly than that of the ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA (Table 1). As follows from the ‘energy’ profiles (Fig. 7), the disadvantage of the ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA lies in the high cost of deformation at the ‘kink-and-slide’ steps (positions ±58, ±48, ±36). By contrast, the deformation values are relatively low for the α-satellite sequence, where CA:TG dimers occupy these positions. Our results thus suggest that the crystallized nucleosomal sequence has been selected to accommodate the changes in base-pair Slide responsible for the superhelical path of nucleosomal DNA.

At the same time, there are two peaks in the α-satellite ‘energy’ profile, corresponding to the presence of AG:CT dimers in ‘kink-and-slide’ configurations at positions ±17 and ±7. This dimer is among the least favorable in terms of the cost of such deformations (see Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table S3, where the mean ‘energy’ of AG:CT dimers in ‘kink-and-slide’ states is second highest, following AT). The high scores at these steps immediately suggest a strategy for further ‘improvement’ of the affinity of the α-satellite DNA for the histone octamer — namely, replacement of the sequences in the above cited positions by sequences containing flexible TA or CA:TG dimers.

Also included in Table 1 are the contributions to the threading ‘energy’ from individual step parameters. The data show that even though DNA is tightly wrapped on the surface of the nucleosome, the cost of DNA bending (primarily via Roll) is not the only significant contribution to the total deformation score. Notably, the deformations in Slide make a contribution to the total score that is comparable to, if not greater than, that from Roll. The large cost of Slide occurs in both the α-satellite and ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA. Moreover, the contribution of Slide is the only term that is significantly lower (∼ 50%) for the α-satellite sequence compared to ‘mixed-sequence’ DNA. Indeed, these trends persist if the same DNA is threaded on other currently known nucleosomal templates (Fei Xu and WKO, unpublished data).

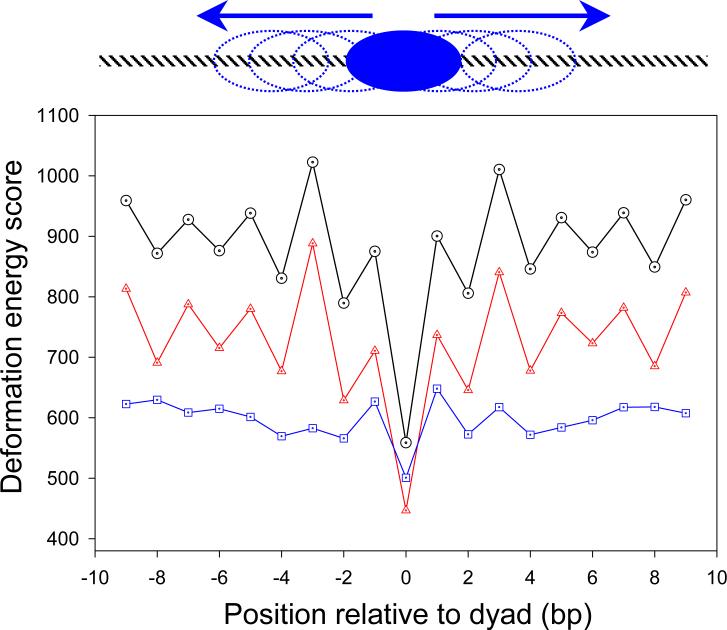

The importance of Slide in the positioning of nucleosomes is underscored in Figure 8, where deformation ‘energies’ are reported for fragments of the human α-satellite sequence in different settings on a shortened nucleosomal template. (The choice of template, the central 129 bp in the best-resolved crystal structure,8 is based on the following considerations: (i) the template has to be shorter than 147 bp — otherwise, threading is impossible; (ii) most of the curvature of nucleosomal DNA is localized in this 129-bp fragment.1) As is clear from the figure, the ‘energies’ are highly sensitive to the setting of the 147-bp sequence on the shortened template. There is a noticeable minimum in the computed ‘energy’ when the ‘natural’ sequence is in register with the observed structure. The score is increased by 20−30% if the sequence is displaced by one or more base pairs. Moreover, the alignment preference nearly disappears if the contribution from Slide is omitted from the computation, but persists if the contribution from Roll is removed. This sensitivity to Slide lends further support to the idea that nucleosome positioning reflects the capability of a sequence to adopt large values of Slide.

Figure 8.

Cost of ‘threading’ the 147-bp human α-satellite sequence on the spatial pathway of nucleosomal DNA. The structural template8 is shortened to 129 bp by removing the straight, 9-bp pieces at either end of the superhelical pathway (129 = 147 – 9 × 2). This allows for 19 (19 = 1 + 9 × 2) different positions of the sequence fragment with respect to the structural template. The shift of one position relative to the other is reported along the abscissa (shown schematically in the upper part of the figure). The total deformation ‘energies’ of the different 129-bp long fragments are depicted by the black circles. The ‘energies’ of the corresponding fragments without consideration of Roll are noted by the red triangles, and those without consideration of Slide by the blue squares. See legend to Table 1 for details of the latter computations.

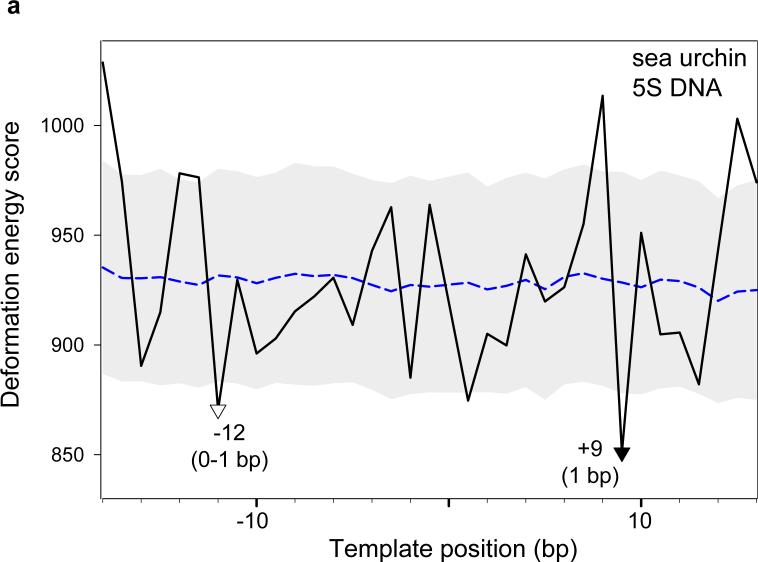

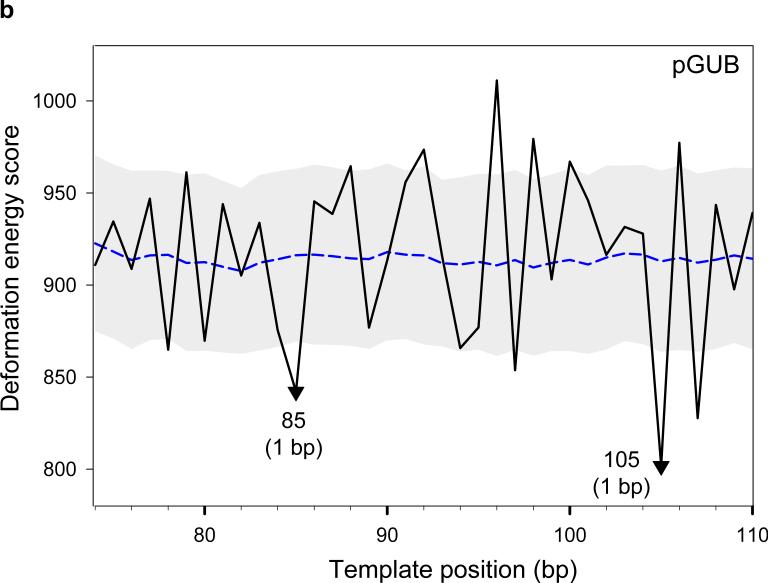

To check the predictive strength of our approach, we analyzed several sequences, for which nucleosome positions have been precisely located experimentally (Fig. 9). The sea urchin 5S rRNA gene sequence is one of the best-characterized positioning sequences,22 where the nucleosomal dyad positions have been mapped to single-nucleotide resolution by site-directed hydroxyl-radical cleavage.23 As seen in Fig. 9a, the deepest minimum in the 5S deformation ‘energy’ profile corresponds to one of the two detected nucleosome positions (base pair +8). Another observed position (base pairs –11/–12) is consistent with the second strongest minimum (base pair –12). The two nucleosome positions are separated by approximately two helical turns of DNA; that is, the nucleosomes are ‘in phase’ and have nearly the same rotational orientation. Thus, using the DNA deformation energy score, we correctly predict both rotational and translational positioning of 5S DNA nucleosomes with an error not exceeding 1 bp.

Figure 9.

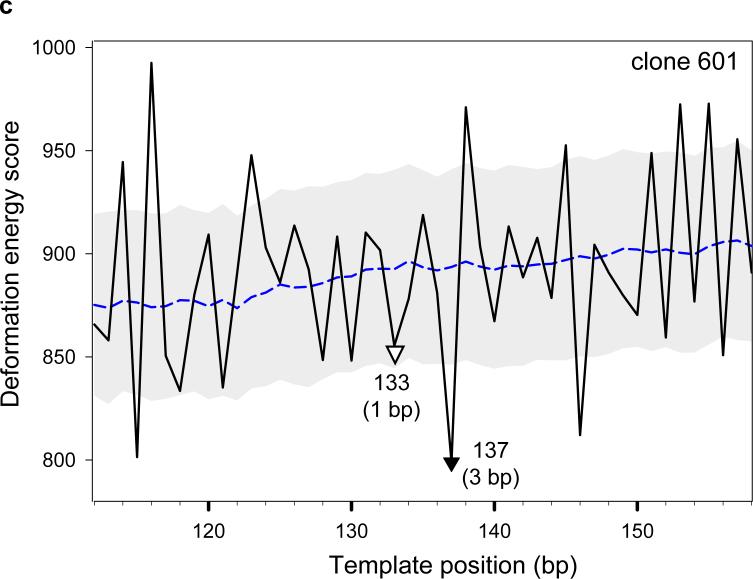

Deformation ‘energy’ profiles of nucleosome-positioning sequences. (a) The sea urchin 5S rRNA gene.22 ‘Energies’, obtained by ‘threading’ the sequence on a template made up of the 147 bp of the crystal structure,8 are compared against nucleosome positions mapped with single-nucleotide resolution at base pairs –11/–12 and +8 on the 180-bp sequence (clone ASYM180 in ref. 23). The base pairs are numbered relative to the transcription start site (+1); note that there is no zero position. The two major minima in the ‘energy’ profile, which are denoted by triangles (the filled triangle corresponding to the deepest minimum), are taken as ‘predicted’ dyad positions. The accuracy of the predictions is shown in parentheses at each minimum. (b) The 183-bp sequence from the pGUB plasmid.24 Experimental dyad positions, found by photochemical cross-linking and subsequent cleavage of DNA photoadducts formed with the modified amino acids of the histone core, occur at base pairs 84 and 104. (c) The 232-bp synthetic high-affinity sequence ‘601’ with the dyad positioned at base pair 134 (J. Widom, personal communication). Note that, in addition to the deepest minimum in the energy profile at base pair 137, there is a secondary minimum at base pair 133 (1 bp from the experimental dyad position). (d) The 195-bp fragment from the sequence of the chicken β-globinA gene ,25 with base pairs numbered relative to the transcription start site (+1). The experimental dyad position (nucleosome 5A), determined by enzymatic (MNase and DNase I) digestion, lies on base pair –281. The threading scores of the sequences (black lines) are compared at each test position with the mean scores (points forming the blue dashed lines) and standard deviations (values equal to half the width of the gray corridors) of a set of 1,000 random sequences with the same dimer composition as the 147-bp fragment centered at the given position. Note that all ‘optimal’ points in the energy profiles fall outside these bounds, i.e., the predicted dyad positions are statisically significant.

The deformation ‘energy’ profiles for three other sequences are also shown in Fig. 9. The 183-bp sequence from the pGUB plasmid,24 like sea urchin 5S DNA, has two characterized nucleosome positions separated by 20 bp. The calculated profile reproduces this behavior correctly, predicting these positions with 1-bp accuracy (Fig. 9b). The next example is the high-affinity synthetic sequence ‘601’ obtained in sequence-selection (SELEX) experiments,4 for which the nucleosome position is predicted with 3-bp accuracy (Fig. 9c). The lower accuracy in this case may reflect the limitations of our model: (i) all DNA sequences are threaded on the same ‘rigid’ nucleosomal template, and (ii) the DNA deformation ‘energy’ is estimated with a simple dimeric model15. We expect that using a ‘flexible’ template that accounts for sequence-related variations in the nucleosomal DNA pathway, and introducing a trimeric model would improve the accuracy of our predictions.

We base these expectations on several ‘unusual’ features that distinguish the ‘601’ sequence from ‘natural’ genomic DNA. First, the ‘601’ sequence has an unusually frequent occurrence of GC-clusters periodically alternating with AT-clusters (e.g., trimers SSS and WWW, where S is G or C, and W is A or T). Most of the SSS trimers lie in major-groove sites and most of the WWW trimers in minor-groove sites in the experimental nucleosome position (base pair 134). Although the distribution of AT-rich and GC-rich clusters is consistent with those observed in chicken and yeast nucleosome core particles,26,28 the periodic positioning of GC-clusters is much more pronounced in the ‘601’ sequence than in genomic DNA. In addition, the ‘601’ sequence is characterized by an exceptionally high fraction of CG dimers, 9% compared to 1−3% in ‘bulk’ eukaryotic DNA, and six of these CG dimers are located in major-groove sites. That is, GC-clusters in general and CG dimers in particular, demonstrate a very strong preference for major-groove bending in the observed nucleosome position (base pair 134).

By contrast, many of these dimers are found in minor-groove sites in the nucleosome position where our ‘energy’ score has the deepest minimum (base pair 137). This is a consequence of the relatively ‘minor-philic’ behavior of the CG dimers predicted by the knowledge-based ‘energy’ function15. We anticipate that the atypical ‘minor-philic’ behavior of the CG dimers will disappear when we use a trimeric instead of a dimeric model and that incorporation of such a model will help, at least in part, to evaluate the many electrostatic interactions of nucleosomal DNA with histone arginines. In particular, consideration of the DNA trimer as a structural unit will incorporate the propeller and buckle angles of base pairs that appear to determine the minor groove width and any accompanying electrostatics effects. The GC-tracts should be less attractive to histone arginines (compared to AT-tracts), and as a consequence, the ‘energetically optimal’ nucleosome sequences should have the GC-tracts bent into the major groove (i.e., consistent with the observed nucleosome position of the ‘601’ sequence).

Finally, the deformation scores predict the arrangement of the fragment from the chicken β-globinA gene 25 correctly, within 1 bp of the single observed nucleosome-binding position (Fig. 9d). This sequence is of special interest because of its high GC-content (64% [G+C] compared to 45% [G+C] for the 5S DNA from sea urchin). Accurate prediction of the nucleosome positioning of such sequences is critical for deducing the structure of chromatin in genomes of higher organisms, where the transcription start sites of many genes are surrounded by highly GC-rich sequences, such as CpG islands. The successful prediction of nucleosome positioning for sequences of various GC-content, including a GC-rich sequence, demonstrates a potential advantage of our ‘structural’ approach, based on calculations of the DNA deformation ‘energy.’

DISCUSSION

Non-elastic behavior of DNA

Looking at the nucleosome core-particle structure from a fresh perspective reveals the unexpected effect of the local base-pair slide on the global superhelical pathway of nucleosomal DNA (Figs. 1-3). This surprising observation adds to the growing list of cases where the classic ribbon model of DNA deformability breaks down. For example, single DNA molecules show clear non-elastic behavior upon imposed extension,29,30 exhibiting the counterintuitive response in twist anticipated by atomic-level calculations,31 i.e., the molecule overwinds rather that underwinds under tension. Such findings illustrate how the DNA chemical architecture can reveal itself at the mesoscale level, i.e., several base pairs, directing the way in which the molecule as a whole responds to strong external forces. In the case of the nucleosome, the tight wrapping of DNA around the core of histone proteins brings about the lateral displacement (shearing) of successive base pairs, which is expressed, in turn, through the superhelical pitch.

The conventional, smoothly-deformed model of superhelical DNA,1,20 by contrast, (i) ignores the shearing of base-pair planes, (ii) defines superhelical pitch in terms of the projection of the base-pair rise on the superhelical axis, and (iii) links changes in superhelical pitch to DNA twisting. Here we see that nucleosomal DNA wraps around the histone core via Roll and Slide, with the base-pair twisting (although varying in strongly deformed steps) remaining close, on average, to that in solution.1

‘Kink-and-slide’ mechanism

Thus, the folding of ‘real’ nucleosomal DNA involves a ‘kink-and-slide’ mechanism (Fig. 5), in which the superhelix is formed through the concerted bending and shearing of appropriate base-pair steps. That is, in addition to the kinks, or ‘hinges’,18 long anticipated to compact DNA on the nucleosome,32,33 there is a translational degree of freedom, i.e., slippage, at the ‘hinges’, which acts to convert a planar, circular fold to a three-dimensional, superhelical configuration. Importantly, these distortions do not affect the overall twisting of DNA. Such a mechanism undoubtedly influences the topological properties of DNA in chromatin 20 and widens the range of potential pathways for histone-modification enzymes to remodel nucleosomes without the necessity of peeling DNA off the protein core. The added degree of conformational freedom clearly facilitates the kinds of DNA rearrangements anticipated in popular mechanisms of chromatin remodeling — DNA ‘bulge’ propagation around the surface of the histone octamer and superhelical displacement via so-called ‘lateral cross transfer’34,35 (both leading to DNA translocation).

The most pronounced ‘kink-and-slide’ distortions of nucleosomal DNA occur near the ends of the bound duplex, interacting with the H2A/H2B histones, e.g., superhelical locations ±5.5 to ±3.5 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1); step positions ±58, ±48, ±36 relative to the dyad (Supplementary Fig. S1). By contrast, the central part of DNA wraps around the H3/H4 tetramer by means of relatively ‘smooth’ bending, with the deformation distributed over several consecutive steps, e.g., see Roll and Slide values at dinucleotide steps ±17 to ±15 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Both ‘smooth’ bends and kinks, however, result in similar DNA configurations with very narrow minor grooves, which are stabilized by interactions of penetrating arginine side-groups. More importantly, the Slide-controlled displacements along the superhelical axis accumulate in a similar fashion, in the both the H3/H4 and the H2A/H2B parts of the nucleosome (Fig. 4). In other words, the present assessment of the effect of base-pair slide on the superhelical path of nucleosomal DNA is valid for both modes of DNA distortions, ‘smooth’ bends and sharp kinks. Whether the difference between wrapping modes in the central and terminal parts of nucleosomal DNA is related to inherent differences in histone binding, or is a consequence of specific DNA sequence, will remain unclear until more high-resolution structures are determined.

New perspective on A-tracts

In this regard, it is noted that the kinking of DNA containing a 16-bp poly(dA·dT) element differs from that of α-satellite DNA assembled with the same type of histones.1,8,36 The TA at step –16, in the vicinity of H3/H4, adopts a ‘kink-and-slide’ state in the recently published, albeit more poorly resolved, nucleosome structure with a long A-tract,36 suggesting that certain sequences can, in principle, accommodate sharp kinks in the central H3/H4 part of the nucleosome. Interestingly, the new minor-groove kink entails one of the flexible dimers, TA, found to be most amenable to such distortion and occurs next to position –17, one of the sites suggested above as a strategy for increasing the affinity of the α-satellite DNA for the histone octamer. Unfortunately, the 3 Å resolution of the new structure precludes detailed comparison between the conformation of the bound A-tract and the α-satellite sequence.

Traditionally, it has been assumed that AA:TT dimers, particularly those in so-called A-tracts, are among the most significant positioning ‘signals’ in nucleosomal DNA.37 This concept has been further corroborated by the nucleosome-binding properties of AT-rich sequences from chicken26 and yeast;28 in both cases, AA:TT dimers are positioned periodically, predominantly in locations where the minor groove faces the histone octamer. Such observations tacitly imply that these dimers are bent into the minor groove. In the nucleosome core-particle structure,8 however, there are no AA:TT dimers significantly bent into the minor groove (see Supplementary Fig. S1), nor are there any such extreme states in either the crystal structures of other protein-DNA complexes or the NMR and X-ray structures of ‘pure’ DNA A-tracts (Supplementary Fig. S3).38 Instead, AA:TT dimers in the nucleosome are often located next to CA:TG minor-groove kinks — for example, the AAAA fragment adjacent to CA at step ±48 and the TTT adjacent to TG at step ±36 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Thus, we see that the AA:TT dimers (and short A-tracts) are not themselves deformed. Apparently, their positioning role is to bring the DNA sequence in register with the histone-octamer template — namely, to secure the most bendable DNA motifs adjacent to key histone arginines, which interact with the narrow minor groove formed by the AA:TT dimers (and A-tracts) 6 and seemingly facilitate the kinking and wrapping of DNA around the protein core.

Role of pyrimidine-purine dimers

In the α-satellite DNA incorporated in nucleosome crystals 5,8 the role of the bendable motif is played by the CA:TG dimeric steps, which undergo sharp minor-groove bends with concomitant displacement via Slide (Fig. 2). Analysis of other protein-DNA structures indicates that one other pyrimidine-purine dimer, TA, is also likely to accommodate this kind of ‘kink-and-slide’ arrangement (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S2). The potential importance of appropriate TA-step positioning for nucleosome stability is supported by the results of in vitro sequence-selection (SELEX) experiments, which identify high-affinity nucleosomal sequences.4,39 Many of these and other high-affinity sequences 2,3 contain periodically positioned TA steps. Moreover, the TA dimers and TTAA tetramers in most of these sequences occupy positions that correspond to sites of minor-groove bending (±36, ±26, ±16, ±6 relative to the dyad); see Figure 4 in ref. 39.

Thus, we conclude that the proper positioning of pyrimidine-purine dimers (CA:TG and TA steps in particular) is one of the key factors determining the formation of nucleosomes. But, if earlier40 it was assumed that pyrimidine-purine positioning is critical for diminishing the cost of DNA bending (Supplementary Fig. S2), now we see that large base-pair sliding, which controls the overall pitch of nucleosomal DNA (Fig. 3), is no less important. The cost of imposing a specific ‘kink-and-slide’ conformation on a base-pair step, estimated with knowledge-based elastic functions,15 varies significantly among the 10 unique dimers (Fig. 6, Supplementary Table S3). The low cost of deformations at CA:TG and TA steps suggests a novel molecular mechanism by which nucleosomes are positioned — namely, placement of these flexible dimers at sites where the minor groove faces the histones (Fig. 7).

DNA threading and nucleosome positioning

To test the applicability of this mechanism for predicting the positions of nucleosomes, representative DNA sequences were ‘threaded’ on the best-resolved nucleosome core-particle structure (Table 1, Figs. 8-9). The total deformation ‘energies’ of sequences forced to adopt the observed three-dimensional pathway account with remarkable accuracy for the experimentally known settings of nucleosomes. For example, the deformation score of the crystallized α-satellite sequence increases substantially when displaced relative to its observed ‘natural’ position on the structural template (Fig. 8). Other DNA sequences, which are known to position nucleosomes in solution, show similar, albeit smaller, dips in the total deformation energy close to the observed ‘natural’ settings (Fig. 9).

The ability to account for the positioning of nucleosomes in terms of the sequence-specific properties of successive base pairs is one of the principal advantages of a ‘structural’ approach in deciphering the organization of chromatin. Such a model offers physical insight into gene regulatory phenomena not possible from a bioinformatics perspective, such as mechanisms that promote the binding of transcription factors to sites on nucleosomal DNA with the requisite exposure and shape to accommodate a ‘tight fit’ on the nucleosome.41-44 (The tumor suppressor protein p53 is among the regulatory factors effectively recognizing DNA packaged in chromatin.45 Note in this regard that the ‘Roll-and-Slide’ deformation of nucleosomal DNA is similar to the DNA conformation induced by the binding of p53 tetramers.46 Apparently, wrapping DNA around the histone core facilitates p53 binding by exposing the cognate DNA site in the conformation most favorable for p53-DNA recognition.) Our method is also well suited to the analysis of genomic sequences of arbitrary base composition, such as GC-rich regulatory sequences from the genomes of higher organisms.

METHODS

Base-pair step parameters

We make use of a dimeric representation of DNA, which incorporates the known effects of base sequence on the intrinsic structure and deformability of the constituent base-pair steps. The conformation of each dimer is described by six independent step parameters which specify the orientation and displacement of neighboring base-pair planes — three angular variables Tilt, Roll, and Twist and three translational variables Shift, Slide, and Rise.12 Values of these parameters are computed with the 3DNA software package,17 which incorporates a recently recommended reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry47 and a rigorous matrix-based scheme.13,48,49 Importantly, the same matrix formalism is used here both to calculate local conformational parameters and to rebuild structures from these parameters.

Knowledge-based deformation ‘energies’ and DNA ‘threading’

The nucleosome-binding affinity of a given DNA sequence is estimated by ‘threading’ the constituent base pairs on the three-dimensional pathway found in the nucleosome core-particle structure8 and calculating a knowledge-based deformation score15 in terms of the deviations of the base-pair step parameters that make up the structure from their preferred equilibrium values.

The total ‘energy’ E of the threaded sequence is expressed as a sum of quadratic terms:

| (1) |

Here Δθni = θni − θ0i (MN) is the imposed deviation of the i-th step parameter θni at the n-th dinucleotide step from the equilibrium rest-state value θ0i (MN) of the MN dimer step. Thefij (MN) are stiffness constants determined by the MN sequence, and N= 146 is the number of base-pair steps that comprise the nucleosome template. The rest-state values of the 16 dinucleotide steps are equated to the average step parameters in known protein-DNA crystal complexes (other than nucleosomes), and the stiffness constants are extracted from the pairwise covariance of these variables.15 Such an approach accounts for the known correlations of dinucleotide step parameters,16 which are especially important for modeling the severe bending and shear deformations of nucleosomal DNA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support of this work through USPHS grant GM20861, the Program in Mathematics and Molecular Biology based at Florida State University (predoctoral fellowship support to AVC), and the Rutgers Center for Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science (National Science Foundation REU award to DM) is gratefully acknowledged. AVC acknowledges support of a predoctoral traineeship from the U.S. Public Health Service (Molecular Biophysics Training Grant GM08319). We also wish to thank Feng Cui, Sergei Grigoryev, Tom Tullius, Fei Xu, Jon Widom, and Cynthia Wolberger for sharing unpublished data and for valuable discussions, and Konstantin Virnik for help with analysis of nucleosome-positioning sequences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Richmond TJ, Davey CA. The structure of DNA in the nucleosome core. Nature. 2003;423:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature01595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrader TE, Crothers DM. Artificial nucleosome positioning sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:7418–7422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Widlund HR, Cao H, Simonsson S, Magnusson E, Simonsson T, Nielsen PE, Kahn JD, Crothers DM, Kubista M. Identification and characterization of genomic nucleosome-positioning sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:807–817. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowary PT, Widom J. New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:19–42. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harp JM, Hanson BL, Timm DE, Bunick GJ. Asymmetries in the nucleosome core particle at 2.5 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2000;56:1513–1534. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900011847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White CL, Suto RK, Luger K. Structure of the yeast nucleosome core particle reveals fundamental changes in internucleosome interactions. EMBO J. 2001;20:5207–5218. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davey CA, Sargent DF, Luger K, Maeder AW, Richmond TJ. Solvent mediated interactions in the structure of the nucleosome core particle at 1.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:1097–1113. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsunaka Y, Kajimura N, Tate S, Morikawa K. Alteration of the nucleosomal DNA path in the crystal structure of a human nucleosome core particle. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3424–3434. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travers AA, Klug A. The bending of DNA in nucleosomes and its wider implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1987;317:537–561. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1987.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scipioni A, Pisano S, Anselmi C, Savino M, De Santis P. Dual role of sequence-dependent DNA curvature in nucleosome stability: the critical test of highly bent Crithidia fasciculata DNA tract. Biophys. Chem. 2004;107:7–17. doi: 10.1016/S0301-4622(03)00214-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickerson RE, Bansal M, Calladine CR, Diekmann S, Hunter WN, Kennard O, von Kitzing E, Lavery R, Nelson HCM, Olson WK, Saenger W, Shakked Z, Sklenar H, Soumpasis DM, Tung C-S, Wang AH-J, Zhurkin VB. Definitions and nomenclature of nucleic acid structure parameters. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;208:787–791. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhurkin VB, Lysov YP, Ivanov VI. Anisotropic flexibility of DNA and the nucleosomal structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:1081–1096. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.3.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulyanov NB, Zhurkin VB. Sequence-dependent anisotropic flexibility of BDNA. A conformational study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1984;2:361–385. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1984.10507573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson WK, Gorin AA, Lu XJ, Hock LM, Zhurkin VB. DNA sequence-dependent deformability deduced from protein-DNA crystal complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11163–11168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorin AA, Zhurkin VB, Olson WK. B-DNA twisting correlates with base-pair morphology. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:34–48. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu XJ, Olson WK. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–5121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schellman JA. Flexibility of DNA. Biopolymers. 1974;13:217–226. doi: 10.1002/bip.1974.360130115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuller FB. The writhing number of a space curve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1971;68:815–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crick FH. Linking numbers and nucleosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:2639–2643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuller FB. Decomposition of the linking number of a closed ribbon: a problem from molecular biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1978;75:3557–3561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson RT, Stafford DW. Structural features of a phased nucleosome core particle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:51–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flaus A, Luger K, Tan S, Richmond TJ. Mapping nucleosome position at single base-pair resolution by using site-directed hydroxyl radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:1370–1375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassabov SR, Henry NM, Zofall M, Tsukiyama T, Bartholomew B. High-resolution mapping of changes in histone-DNA contacts of nucleosomes remodeled by ISW2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7524–7534. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7524-7534.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davey CS, Pennings S, Reilly C, Meehan RR, Allan J. A determining influence for CpG dinucleotides on nucleosome positioning in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4322–4331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satchwell SC, Drew HR, Travers AA. Sequence periodicities in chicken nucleosome core DNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;191:659–675. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drew HR, Calladine CR. Sequence-specific positioning of core histones on an 860 base-pair DNA. Experiment and theory. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;195:143–173. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segal E, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Chen L, Thåström A, Wang J-PZ, Widom J. Genomes utilize a nucleosome positioning code to achieve biological function. Nature. 2006;442:772–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gore J, Bryant Z, Nollmann M, Le MU, Cozzarelli NR, Bustamante C. DNA overwinds when stretched. Nature. 2006;442:836–839. doi: 10.1038/nature04974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lionnet T, Joubaud S, Lavery R, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Wringing out DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;96:178102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.178102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosikov KM, Gorin AA, Zhurkin VB, Olson WK. DNA stretching and compression: large-scale simulations of double helical structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;289:1301–1326. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crick FH, Klug A. Kinky helix. Nature. 1975;255:530–533. doi: 10.1038/255530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobell HM, Tsai CC, Gilbert SG, Jain SC, Sakore TD. Organization of DNA in chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1976;73:3068–3072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.9.3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lusser A, Kadonaga JT. Chromatin remodeling by ATP-dependent molecular machines. Bioessays. 2003;25:1192–200. doi: 10.1002/bies.10359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flaus A, Owen-Hughes T. Mechanisms for ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling: farewell to the tuna-can octamer? Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2004;14:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bao Y, White CL, Luger K. Nucleosome core particles containing a poly(dA·dT) sequence element exhibit a locally distorted DNA structure. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:617–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trifonov EN, Sussman JL. The pitch of chromatin DNA is reflected in its nucleotide sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:3816–3820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhurkin VB, Tolstorukov MY, Xu F, Colasanti AV, Olson WK. “Sequence-dependent variability of B-DNA: an update on bending and curvature,”. In: Ohyama T, editor. DNA Conformation and Transcription. 2004. LANDES Bioscience. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thåström A, Bingham LM, Widom J. Nucleosomal locations of dominant DNA sequence motifs for histone-DNA interactions and nucleosome positioning. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhurkin VB. Specific alignment of nucleosomes on DNA correlates with periodic distribution of purine-pyrimidine and pyrimidine-purine dimers. FEBS Lett. 1983;158:293–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80598-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cordingley MG, Riegel AT, Hager GL. Steroid-dependent interaction of transcription factors with the inducible promoter of mouse mammary tumor virus in vivo. Cell. 1987;48:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Workman JL, Kingston RE. Nucleosome core displacement in vitro via a metastable transcription factor-nucleosome complex. Science. 1992;258:1780–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1465613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kingston RE. A snapshot of a dynamic nuclear building block. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:763–766. doi: 10.1038/nsb1097-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Angelov D, Lenouvel F, Hans F, Muller CW, Bouvet P, Bednar J, Moudrianakis EN, Cadet J, Dimitrov S. The histone octamer is invisible when NF-kappaB binds to the nucleosome. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42374–42382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Espinosa JM, Emerson BM. Transcriptional regulation by p53 through intrinsic DNA/chromatin binding and site-directed cofactor recruitment. Mol. Cell. 2001;8:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durell SR, Jernigan RL, Appella E, Nagaich AK, Harrington RE, Zhurkin VB. DNA bending induced by tetrameric binding of the p53 tumor suppressor protein: steric constraints on conformation. In: Sarma RH, Sarma MH, editors. Structure, Motion, Interaction and Expression of Biological Macromolecules. Proceedings of the Tenth Conversation, 1997. Vol. 2. Adenine Press; New York: 1998. pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olson WK, Bansal M, Burley SK, Dickerson RE, Gerstein M, Harvey SC, Heinemann U, Lu X-J, Neidle S, Shakked Z, Sklenar H, Suzuki M, Tung C-S, Westhof E, Wolberger C, Berman HM. A standard reference frame for the description of nucleic acid base-pair geometry. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;313:229–237. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bolshoy A, McNamara P, Harrington RE, Trifonov EN. Curved DNA without A-A: experimental estimation of all 16 DNA wedge angles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:2312–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.El Hassan MA, Calladine CR. The assessment of the geometry of dinucleotide steps in double-helical DNA; a new local calculation scheme. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;251:648–664. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang CC, Couch GS, Pettersen EF, Ferrin TE. Chimera: an extensible molecular modeling application constructed using standard components. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing. 1996;1:724. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.