Abstract

Most human cancers are characterized by genetic instabilities. Chromosomal aberrations include segments of allelic imbalance identifiable by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at polymorphic loci, which may be used to implicate regions harboring tumor suppressor genes. Here we performed whole genome LOH profiling on over 40 human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell lines. Several frequent LOH regions have been identified on chromosomal arms 3p, 4p, 4q, 5q, 8p, 9p, 10p, 11q, and 17p. A genomic region of ∼7 Mb located at 8p22-p21.3 exhibits the most frequent LOH (87.9%), which suggested that this region harbors important tumor suppressor gene(s). Mitochondrial tumor suppressor gene 1 (MTUS1) is a recently identified candidate tumor suppressor gene that resides in this region. Consistent down-regulation in expression was observed in HNSCC for MTUS1 as measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Sequence analysis of MTUS1 gene in HNSCC revealed several important sequence variants in the exon regions of this gene. Thus, our results suggested that MTUS1 is one of the candidate tumor suppressor gene(s) reside in 8p22-p21.3 for HNSCC. The identification of these candidate genes will facilitate the understanding of tumorigenesis of HNSCC. Further studies are needed to functionally evaluate those candidate genes.

Introduction:

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the head and neck is one of the most common cancers. In the United States there are over 31,000 new cases of head and neck / oral squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) each year [1]. It will cause over 8,000 deaths, killing roughly 1 person per hour. Worldwide the problem is much worse, with over 270,000 new cases being diagnosed each year [2]. In some parts of the world, including Melanesia, France and the Indian subcontinent, HNSCC is a major health problem [3]. The overall 5-year survival rates for HNSCC have remained at approximately 50%, considerably lower than cervical cancer, Hodgkin's disease, cancer of the brain, liver, testes, kidney, or skin cancer (malignant melanoma) [2]. Tobacco, alcohol, viral infections as well as genetic polymorphisms on genes that metabolize carcinogens are common risk factors for HNSCC [4, 5]. Several chromosome regions have been identified to be frequently altered in HNSCC, including 3p, 4q, 5q21−22, 8p21−23, 9p21−22, 11q13, 11q23, 13q, 14q, 17p, 18q and 22q [6]. However, significant improvement of functional mapping is needed to move the HNSCC diagnosis, treatment and research forward.

Most human cancers are characterized by genetic instabilities [7]. Chromosomal aberrations include segments of allelic imbalance identifiable by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at polymorphic loci, and may be used to implicate regions harboring tumor suppressor genes [8-10]. LOH patterns can be generated through allelotyping using polymorphic microsatellite markers. However, due to the limited number of available microsatellite markers, the tedious and labor intensive procedure, and the requirement of large amount of DNA, only a modest number of microsatellite makers can be screened. The recent advances in high-density single nucleotide polymorphic allele (SNP) array platform provide unique opportunity to generate LOH profile with high resolution. Our previous studies demonstrated the feasibility of using the Affymetrix 10K SNP Mapping Array for genome-wide LOH profiling [11-13].

In this study, using SNP array-based LOH profiling on a large panel of HNSCC cell lines, we narrowed the frequent LOH region at 8p to an approximately 7 Mb region located at 8p22-p21.3. Mitochondrial tumor suppressor gene 1 (MTUS1) is one of the candidate genes that reside in this genomic region, which was initially identified as a potential tumor suppressor gene in pancreatic cancer [14]. Our recent study suggested that the reduction of MTUS1 expression may be associated with advanced oral tongue SCC [15]. The reduced expression of MTUS1 has also been observed in colon cancer, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer [14, 16, 17]. In this study, our expressional and sequence analyses on MTUS1 gene provide additional evidences to support that MTUS1 may be a tumor suppressor for HNSCC.

Methods and Materials:

The SNP array assay was performed as described previously [11-13]. In brief, the genomic DNAs were isolated from cultured cell lines using the Qiagen genomic DNA isolation kit (see Supplement Table 1 for the descriptions on the cell lines). The labeling, hybridization, washing, and staining of the 10K SNP mapping array was performed according to the standard Single Primer GeneChip Mapping Assay protocol (Affymetrix). The SNP genotype calls were generated using the Affymetrix GeneChip DNA Analysis Software (GDAS). The LOH maps for these cells were generated using the novel informatics platform, dChipSNP [18, 19]. Briefly, a Hidden Markov Model is employed to infer LOH status from SNP calls of each sample and a LOH LOD (Logarithm of the odds) score is computed [20] to evaluate the likelihood that a particular locus harbors a cancer-related gene. Hierarchical clustering based on LOH calls in the specific regions with LOD score exceeding particular threshold was carried out as described previously [21].

To evaluate the expressional changes of MTUS1 genes at mRNA level, the quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed as described previously [15] on 10 HNSCC cell lines and normal oral keratinocyte (NHOK), as well as 10 paired normal and oral tongue cancer tissues samples (see Supplement Table 2 for the descriptions of the oral tongue cancer tissues). The RNA from cell lines was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy kit. For RNA from frozen tissue samples, the cancer tissues containing more than 80% tumor cells based on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and pathological examination were identified and selectively microdissected. The pathologically normal boarders were identified for isolating normal matching RNA. The total RNA was then isolated using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). The RNA was converted to first strand cDNA using MuLV reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) and the quantitative PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) in a BIO-RAD iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system. The primer sets specific for MTUS1 (Forward: 5’-tatctctgctcacgcttcca-3’, Reverse: 5’-cagcagggaacaacacaaga-3’) were used. All reactions were performed in triplicate. The melting curve analyses were performed to ensure the specificity of the qRT-PCR reactions. The data analysis was performed using the 2-delta delta Ct method described previously [22], where beta-actin was used as reference gene.

Sequence analyses were performed for all 17 exons of MTUS1 gene using the primer sets established by Di Benedetto et. al. [23]. The PCR reactions were performed, and the PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and sequenced using a PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) from both directions using the PCR primers. The sequencing results were compared with the homo sapiens chromosome 8 reference sequence (Genebank NC_000008, version 9) and the sequence variants were then identified.

Results and Discussion:

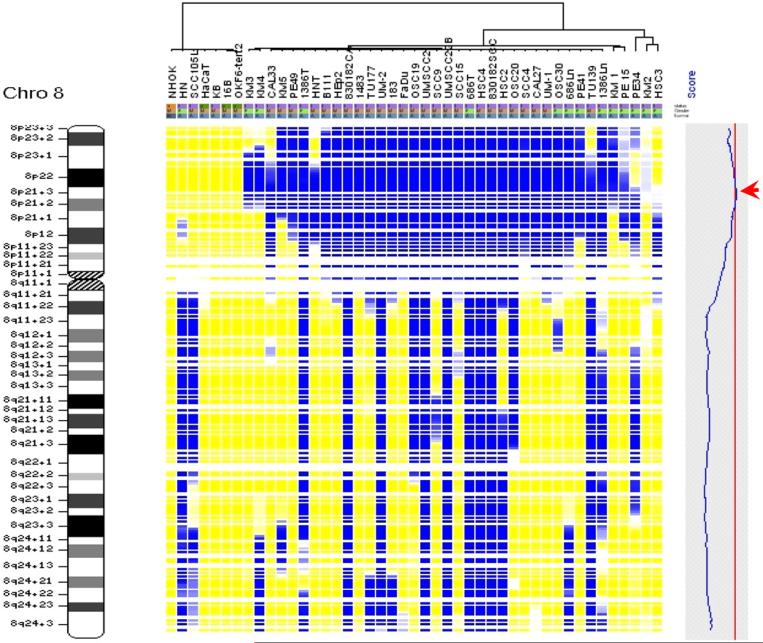

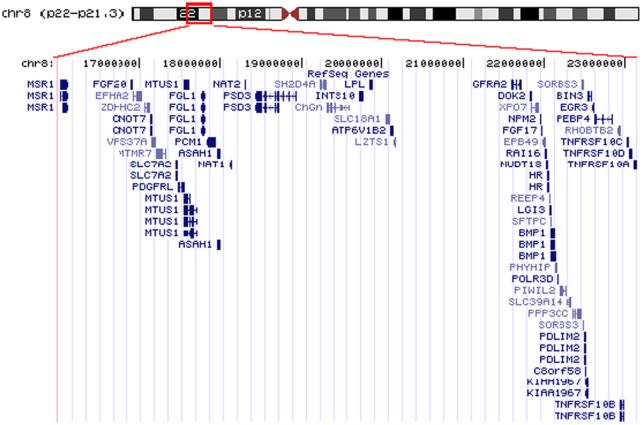

SNP array based LOH profiling was performed as described in the Methods and Materials section on 41 HNSCC cell lines. As references, LOH profiles were also obtained for 2 immortalized normal oral keratinocyte, 1 normal oral keratinocyte primary culture (NHOK) and 1 immortalized skin keratinocyte (HaCaT). While minimum allelic imbalance was observed for the normal keratinocytes, several frequent LOH regions were identified for HNSCC cases (Table 1). Chromosome arms 3p, 4p, 4q, 5q, 8p, 9p, 10p, 11q, 17p exhibit the frequent LOH, which is in agreement with various previous finds [6, 11, 24]. The complete LOH profile for chromosome 8 was shown in Figure 1, where a region of approximately 7 Mb at 8p22−8p21.3 exhibits the most frequent allelic imbalance. This genomic area is a gene-rich region, which contains 55 known genes (Figure 2, and see supplement Table 3 for a complete gene list of this region). Among those genes, there are several known candidate tumor suppressor genes and cancer related genes, including MTUS1, pericentriolar material-1 (PCM1), leucine zipper putative tumor suppressor-1 (LZTS1), deleted in breast cancer 1 (DBC-1), Rho-related BTB domain-containing protein 2 (RHOBTB2), early growth response 3 (EGR3), tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 10A (TNFRSF10A), and member 10B (TNFRSF10B). The MTUS1 gene is a newly identified candidate tumor suppressor gene [14] and the protein product of this gene has been shown to interact with angiotensin II AT2 receptor, and inhibit growth-factor-induced extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and cell proliferation [25, 26]. The protein product of PCM1 gene is a centrosomal protein that exhibits a distinct cell cycle-dependent association with the centrosome complex [27], and has been showed to form fusion protein with RET protooncogene in papillary thyroid carcinoma [28], and with JAK2 in leukemia [29]. The protein product of LZTS1 contains a leucine zipper region with similarity to the DNA-binding domain of the cAMP-responsive activating transcription factor-5, and may involve in cell cycle regulation at late S-G2/M stage [30]. The DBC-1 and RHOBTB2 (also known as DBC-2) genes were shown to be homozygously deleted in breast cancer [31]. EGR3 is a critical transcriptional factor for induction of Fas ligand (FasL) expression [32], and has been shown to be silenced by hypermethylation in adult T-cell leukemia [33]. TNFRSF10A (also known as Death Receptor 4) and TNFRSF10B (also know as Death Receptor 5) are death domain-containing receptors that trigger apoptosis by inducing the oligomerization of intracellular death domains [34].

Table 1.

Frequent LOH regions identified by 10K SNP array assay on HNSCC

| Chromosome arm | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| 3p | 63.4 |

| 4p | 51.2 |

| 4q | 58.5 |

| 5q | 58.5 |

| 8p | 87.8 |

| 9p | 75.6 |

| 10p | 58.5 |

| 11q | 68.3 |

| 17p | 58.5 |

Figure 1.

SNP array based LOH profiles of chromosome 8 in HNSCC

The genomic DNA from each cell lines was assayed using Affymetrix 10K SNP mapping array. The LOH regions were detected and demarcated using dChipSNP as described [18]. Each column represents one cell line, and each row represents a SNP marker. Color code: Blue = LOH; Yellow = retained; Gray = uninformative; White = no call. The relative genomic location was indicated by the cytoband map on the left. The blue curve in the shaded gray box on the right denotes LOD (Logarithm of the odds) score representing the excessive sharing of LOH. The red arrow head designates the most frequent LOH region at chromosome 8p.

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) map: single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array-based LOH profiles of chromosome 8 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). The genomic DNA from each cell lines was assayed using an Affymetrix 10K SNP mapping array. The LOH regions were detected and demarcated using dChipSNP informatics software, as previously described [18]. Each column represents one cell line, and each row presents a SNP marker, with colours as follows: blue, LOH; yellow, retained; gray, uninformative; white, no call. The relative genomic location is indicated by the cytoband map (left). In the shaded gray box (right), the blue curve denotes the logarithm of the odds score (LOD score) representing the excessive sharing of LOH. The red arrowhead designates the most frequent LOH region at chromosome 8p.

Figure 2.

Genes located in the frequent LOH region at 8p22−21.3

The frequent LOH region at 8p22−21.3 was displayed using UCSC Genome Browser. Genes located in this genomic region and their corresponding mRNAs were plotted.

Genes located in the frequent LOH region at 8p21.3∼p22, as displayed using the UCSC Genome Browser (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu). Genes located in this genomic region and their corresponding mRNAs were plotted.

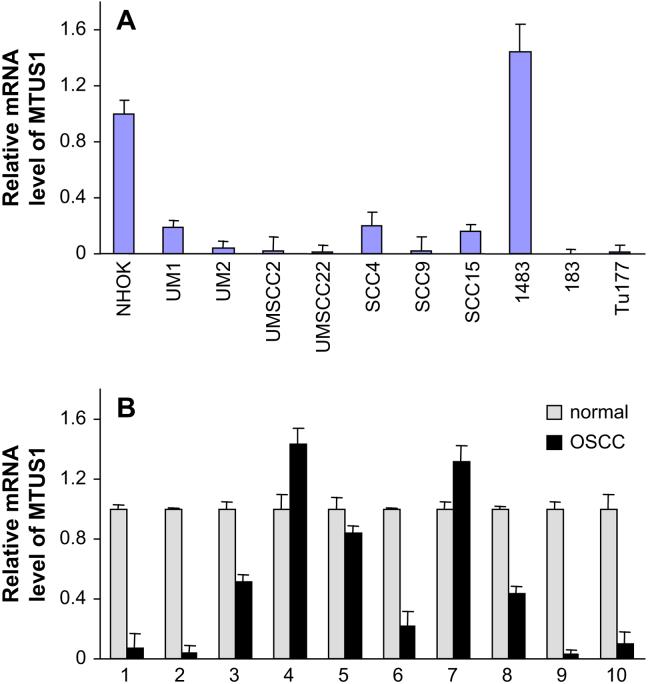

Since our recent study suggested that the reduction of MTUS1 expression may be associated with advanced oral tongue SCC [15], we further investigated expressional changes of this gene in HNSCC. The qRT-PCR analyses were performed on 10 HNSCC cell lines and normal oral keratinocytes (NHOK), as well as 10 paired normal and tongue cancer tissue samples. As illustrated in Figure 3A, 9 out of 10 HNSCC cell lines examined exhibit reduced expression of MTUS1 gene compare to NHOK. Similarly, for the paired tongue cancer and matching normal tissue samples, 7 out of 10 cancer cases samples exhibit reduced expression of MTUS1 gene compare to their corresponding normal controls (Figure 3B). The MTUS1 was initially identified as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in pancreatic cancer [14]. The mature protein product of this gene was suggested to localize to mitochondria [14]. The ectopic expression of MTUS1 gene products has been shown to inhibit the cell proliferation [14, 26]. The reduced expression of MTUS1 has been observed in colon cancer, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer [14, 16, 17]. These results, together with our study suggested that MTUS1 is a potential tumor suppressor gene for HNSCC and is a promising candidate for further functional analysis.

Figure 3.

The mRNA level of MTUS1 in HNSCC.

The qRT-PCR for MTUS1 was performed as described in Methods and Materials. The data analysis was carried out using the 2-delta delta Ct method described previously [22], where beta-actin was used as reference gene. A) The mRNA levels of MTUS1 were evaluated on 10 HNSCC cell lines and normal oral keratinocytes (NHOK). B) The mRNA levels of MTUS1 were evaluated on 10 pairs of tongue SCC cases and matching normal tissue samples.

The mRNA level of MTSU1 in HNSCC. Quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction for MTUS1 was performed as described in Methods and Materials. Data analysis was performed using the 2–ΔΔCt method as described previously [22], with the β-actin gene ACTB used as the reference. (A) The mRNA levels of MTUS1 were evaluated on 10 HNSCC cell lines and normal oral keratinocytes (NHOK). (B) The mRNA levels of MTUS1 were evaluated on 10 pairs of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma cases (OSCC) and matching normal tissue samples.

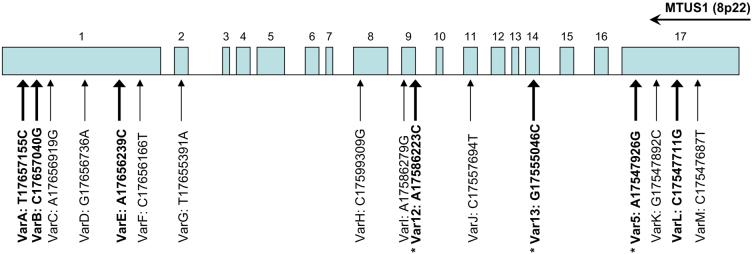

Recent structural analysis of the MTUS1 gene revealed that this gene comprises 17 coding exons [35]. The previous mutation analyses on this gene in liver cancer revealed that this gene is prone to various point mutations and small deletions which lead to the silencing of MTUS1 gene [23]. To evaluate the involvement of mutation / nucleotide substitutions of MTUS1 gene in HNSCC, we carried out sequencing analyses for all 17 exons of the MTUS1 gene on 10 HNSCC cell lines, 183, 1483, FaDu, HEP2, SCC4, SCC9, SCC15, UM1, UM2, UMSCC22B. As shown in Figure 4, 13 single nucleotide sequence variants were observed in exon 1, 2, 8, 9, 11, and 17. Among those nucleotide sequence variants, 4 of them lead to amino acid substitutions, including varA (Cys-Arg), varB (Thr-Ser), varE (Lys-Thr), and varL (Leu-Val) (Figure 5). Four of those sequence variants detected here in HNSCC have been reported in liver cancer recently, including varA, varC, varE, varH [23]. These results, together with previously detected sequence variants in 2 additional oral SCC cell lines (Var5, Var12, Var13, which lead to amino acid substitutions of Gln-Arg, Lys-Thr, Glu-Gln, respectively) [23], suggested that mutation is a common mechanism of silencing the MTUS1 gene in HNSCC. Alternatively, some of these detected sequence variants may represent the germline polymorphisms in the MTUS1 gene. While our sequencing analyses were focused on the exon regions of the gene, it is possible that additional sequence variants may exist in other regions of this gene (e.g., intron, promoter) that may affect the functions of this gene. Additional sequence analyses will be needed to fully explore the extent of the mutational effects on this gene.

Figure 4.

Exonic sequence variations of MTUS1 gene in HNSCC.

The schematic representation of the genomic organization of MTUS1 gene located on the minus strand of chromosome 8p22 was presented. The genomic locations of the detected nucleotide sequence variants for MTUS1 gene in HNSCC were indicated. The nucleotide sequence variants that lead to amino acid changes were identified with bold font. The * indicates the nucleotide sequence variants were identified previously [23].

Exonic sequence variations of MTUS1 gene in HNSCC: a schematic representation of the genomic organization of MTUS1 gene located on the minus strand of chromosome 8p22. The genomic locations of the detected nucleotide sequence variants for MTUS1 gene in HNSCC are indicated. Boldface type identifies the nucleotide sequence variants that lead to amino acid changes. An asterisk marks the nucleotide sequence variants identified previously [23].

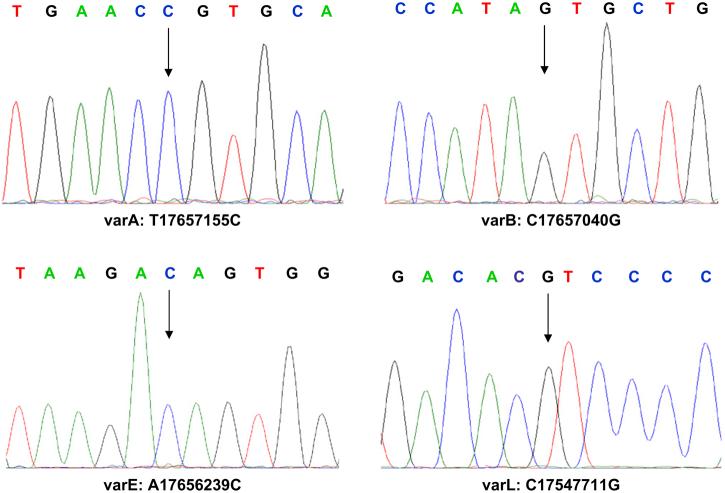

Figure 5.

Sequence analyses of the MTUS1 gene in HNSCC.

Sequence analyses of MTUS1 gene were performed on 10 HNSCC cell lines as described. A total of 13 single nucleotide sequence variants were observed in exon 1, 2, 8, 9, 11, and 17. The representative sequence chromatograms for nucleotide sequence variants varA (Cys-Arg), varB (Thr-Ser), varE (Lys-Thr), and varL (Leu-Val) were presented. The arrows designate nucleotide variants.

Sequence analyses of the MTUS1 gene were performed on HNSCC cell lines as described. A total of 13 single-nucleotide sequence variants were observed, in exons 1, 2, 8, 9, 11, and 17. Shown here are representative sequence chromatograms for nucleotide sequence variants varA (Cys-Arg), varB (Thr-Ser), varE (Lys-Thr), and varL (Leu-Val). Arrows indicate nucleotide variants.

Our results, together with previous findings suggested that MTUS1 is one of the functional tumor suppressor genes in several cancer types. The precise tumor suppressor function of MTUS1 at molecular level is not clearly defined yet. It has been demonstrated that the protein product of MTUS1 gene interacts with angiotensin II AT2 receptor in eukaryotic cells and inhibits growth-factor-induced extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) activation and cell proliferation [25, 26]. Several splicing variants have been observed, each showing different tissue distribution. Comparison of amino acid sequences from different species revealed high conservation of this gene [35], suggesting that protein product of MTUS1 gene may play important roles in cellular homeostasis. Further study will be needed to fully characterize the molecular mechanisms utilized by MTUS1 as a functional tumor suppressor in HNSCC.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported in part by NIH PHS grants K22 DE014847, RO3 DE016569, RO3 CA114688 (to X. Zhou), R01 DE015970 (to D. Wong). The 10K SNP mapping array hybridization and scanning were performed at the UCLA DNA microarray facility. The sequence analyses performed at the UIC Research Resource Center, DNA service facility. The primary NHOK cell and the 183, 1483 OSCC cell lines were gifts from Drs N.H. Park and K.H. Shin of the UCLA. UMSCC2 and UMSCC22B cell lines were gifts from Drs S. Sharma and A. Lichtenstein of the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center. The 830182SCC and 830182CA cell lines were gifts from Drs G. Milo and S. D’Ambrosio of the Ohio State University. MDA686Tu, MDA686Ln, MDA1386Tu, MDA1386Ln cells were gifts from Dr. PG. Sacks of the New York University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary Material

Reference:

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(2):106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1999;80(6):827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazarus P, Park JY. Metabolizing enzyme genotype and risk for upper aerodigestive tract cancer. Oral Oncol. 2000;36(5):421–431. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichart PA. Identification of risk groups for oral precancer and cancer and preventive measures. Clin Oral Investig. 2001;5(4):207–213. doi: 10.1007/s00784-001-0132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagpal JK, Das BR. Oral cancer: reviewing the present understanding of its molecular mechanism and exploring the future directions for its effective management. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(02)00162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, Yu T, Cole SW, Wong DT. Advancement in characterization of genomic alterations for improved diagnosis, treatment and prognostics in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2006;6(1):39–50. doi: 10.1586/14737159.6.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pekarsky Y, Palamarchuk A, Huebner K, Croce CM. FHIT as tumor suppressor: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1(3):232–236. doi: 10.4161/cbt.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zabarovsky ER, Lerman MI, Minna JD. Tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p involved in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21(45):6915–6935. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong JT. Chromosomal deletions and tumor suppressor genes in prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20(3−4):173–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1015575125780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou X, Li C, Mok SC, Chen Z, Wong DTW. Whole Genome Loss of Heterozygosity Profiling on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by High-Density Single Nucleotide Polymorphic Allele (SNP) Array. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;151(1):82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Mok SC, Chen Z, Li Y, Wong DT. Concurrent analysis of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and copy number abnormality (CNA) for oral premalignancy progression using the Affymetrix 10K SNP mapping array. Hum Genet. 2004;115(4):327–330. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X, Rao NP, Cole SW, Mok SC, Chen Z, Wong DT. Progress in concurrent analysis of loss of heterozygosity and comparative genomic hybridization utilizing high density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;159(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seibold S, Rudroff C, Weber M, Galle J, Wanner C, Marx M. Identification of a new tumor suppressor gene located at chromosome 8p21.3−22. Faseb J. 2003;17(9):1180–1182. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0934fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Temam S, Oh M, Pungpravat N, Huang BL, Mao L, Wong DT. Global expression-based classification of lymph node metastasis and extracapsular spread of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2006;8(11):925–932. doi: 10.1593/neo.06430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Bang S, Song K, Lee I. Differential expression in normal-adenoma-carcinoma sequence suggests complex molecular carcinogenesis in colon. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(4):747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pils D, Horak P, Gleiss A, Sax C, Fabjani G, Moebus VJ, Zielinski C, Reinthaller A, Zeillinger R, Krainer M. Five genes from chromosomal band 8p22 are significantly down-regulated in ovarian carcinoma: N33 and EFA6R have a potential impact on overall survival. Cancer. 2005;104(11):2417–2429. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberfarb ME, Lin M, Lechpammer M, Li C, Tanenbaum DM, Febbo PG, Wright RL, Shim J, Kantoff PW, Loda M, et al. Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity analysis from laser capture microdissected prostate cancer using single nucleotide polymorphic allele (SNP) arrays and a novel bioinformatics platform dChipSNP. Cancer Res. 2003;63(16):4781–4785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(8):1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newton MA, Gould MN, Reznikoff CA, Haag JD. On the statistical analysis of allelic-loss data. Stat Med. 1998;17(13):1425–1445. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980715)17:13<1425::aid-sim861>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(25):14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Benedetto M, Pineau P, Nouet S, Berhouet S, Seitz I, Louis S, Dejean A, Couraud PO, Strosberg AD, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, et al. Mutation analysis of the 8p22 candidate tumor suppressor gene ATIP/MTUS1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;252(1−2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin C, Jin Y, Wennerberg J, Annertz K, Enoksson J, Mertens F. Cytogenetic abnormalities in 106 oral squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;164(1):44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wruck CJ, Funke-Kaiser H, Pufe T, Kusserow H, Menk M, Schefe JH, Kruse ML, Stoll M, Unger T. Regulation of transport of the angiotensin AT2 receptor by a novel membrane-associated Golgi protein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(1):57–64. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150662.51436.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nouet S, Amzallag N, Li JM, Louis S, Seitz I, Cui TX, Alleaume AM, Di Benedetto M, Boden C, Masson M, et al. Trans-inactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases by novel angiotensin II AT2 receptor-interacting protein, ATIP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(28):28989–28997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balczon R, Bao L, Zimmer WE. PCM-1, A 228-kD centrosome autoantigen with a distinct cell cycle distribution. J Cell Biol. 1994;124(5):783–793. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corvi R, Berger N, Balczon R, Romeo G. RET/PCM-1: a novel fusion gene in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Oncogene. 2000;19(37):4236–4242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiter A, Walz C, Watmore A, Schoch C, Blau I, Schlegelberger B, Berger U, Telford N, Aruliah S, Yin JA, et al. The t(8;9)(p22;p24) is a recurrent abnormality in chronic and acute leukemia that fuses PCM1 to JAK2. Cancer Res. 2005;65(7):2662–2667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishii H, Vecchione A, Murakumo Y, Baldassarre G, Numata S, Trapasso F, Alder H, Baffa R, Croce CM. FEZ1/LZTS1 gene at 8p22 suppresses cancer cell growth and regulates mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10374–10379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181222898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamaguchi M, Meth JL, von Klitzing C, Wei W, Esposito D, Rodgers L, Walsh T, Welcsh P, King MC, Wigler MH. DBC2, a candidate for a tumor suppressor gene involved in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(21):13647–13652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212516099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittelstadt PR, Ashwell JD. Cyclosporin A-sensitive transcription factor Egr-3 regulates Fas ligand expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(7):3744–3751. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasunaga J, Taniguchi Y, Nosaka K, Yoshida M, Satou Y, Sakai T, Mitsuya H, Matsuoka M. Identification of aberrantly methylated genes in association with adult T-cell leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6002–6009. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hymowitz SG, Christinger HW, Fuh G, Ultsch M, O'Connell M, Kelley RF, Ashkenazi A, de Vos AM. Triggering cell death: the crystal structure of Apo2L/TRAIL in a complex with death receptor 5. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):563–571. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Benedetto M, Bieche I, Deshayes F, Vacher S, Nouet S, Collura V, Seitz I, Louis S, Pineau P, Amsellem-Ouazana D, et al. Structural organization and expression of human MTUS1, a candidate 8p22 tumor suppressor gene encoding a family of angiotensin II AT2 receptor-interacting proteins, ATIP. Gene. 2006;380(2):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.