Abstract

Heart failure in sub‐Saharan Africans is mainly due to non‐ischaemic causes, such as hypertension, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy and pericarditis. The two endemic diseases that are major contributors to the clinical syndrome of heart failure in Africa are cardiomyopathy and pericarditis. The major forms of endemic cardiomyopathy are idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, peripartum cardiomyopathy and endomyocardial fibrosis. Endomyocardial fibrosis, which affects children, has the worst prognosis. Other cardiomyopathies have similar epidemiological characteristics to those of other populations in the world. HIV infection is associated with occurrence of HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy in patients with advanced immunosuppression, and the rise in the incidence of tuberculous pericarditis. HIV‐associated tuberculous pericarditis is characterised by larger pericardial effusion, a greater frequency of myopericarditis, and a higher mortality than in people without AIDS. Population‐based studies on the epidemiology of heart failure, cardiomyopathy and pericarditis in Africans, and studies of new interventions to reduce mortality, particularly in endomyocardial fibrosis and tuberculous pericarditis, are needed.

Keywords: epidemiology, management, cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, sub‐Saharan Africa

The problem of heart failure has been recognised in sub‐Saharan Africa for over 60 years.1 Estimates of the crude incidence of heart failure in the general population of developed countries range from one to five cases per 1000 per year, while the crude prevalence is 3–20 per 1000.2 No population‐based incidence or prevalence studies of heart failure from Africa or other developing countries have been published.2,3 Information on the epidemiology of heart failure in Africa is therefore obtained from hospital‐based studies. These studies indicate that cardiovascular diseases account for 7–10% of all medical admissions to African hospitals, with heart failure contributing to 3–7% of these admissions.4,5

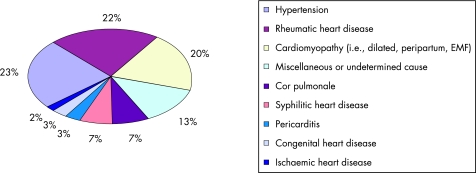

At least 12 clinical studies have examined the aetiology of heart failure in hospitalised Africans over the past 50 years (fig 1).4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 These studies disclose several features of the epidemiology of heart failure that are unique to sub‐Saharan Africa. First, 98% of heart failure cases are due to non‐ischaemic causes, with hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, and cardiomyopathy accounting for 65% of cases. The diagnosis of myocardial infarction was made in only 2% of cases, which confirms the observation that coronary artery disease remains uncommon in black Africa.16 This is not a surprise because the prevalence of risk factors for coronary artery disease, apart from hypertension, remains relatively low in many parts of the sub‐Sahara.17,18,19 It must be noted, however, that the diagnosis of myocardial infarction was made on the basis of electrocardiographic abnormalities in almost all the African studies so far. This method may underestimate the true prevalence of coronary artery disease within a heart failure population.20

Figure 1 Causes of heart failure in sub‐Saharan Africa: combined data from 12 hospital‐based case series conducted between 1957 and 2005 involving 4549 patients from eight countries (Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe). EMF, endomyocardial fibrosis.

Second, the common causes of heart failure in sub‐Saharan Africa, such as rheumatic heart disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PCM),21 and endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF)22 present before middle age, whereas in developed regions of the world, heart failure is a disease of the elderly, with an average age of 76 years.23,24 The early presentation of heart failure in Africans has the potential to undermine national productivity as a consequence of the number of active life years lost by the most productive segment of the population.

Finally, infectious diseases remain a major cause of heart failure in Africans. The contribution of cor pulmonale and pericarditis to about 10% of cases of heart failure reflects the continuing impact of tuberculosis on heart disease (fig 1). Cor pulmonale is mainly related to chronic post‐tuberculosis lung disease, whereas pericarditis, which has been exacerbated by the HIV epidemic, is overwhelmingly due to active tuberculous involvement.25 Syphilitic heart disease has accounted for an average of 7% of cases of heart failure in the hospital series (fig 1). More recent studies, however, show a dramatic reduction in the number of cases of heart failure attributed to syphilis, a development that may be related to the wide use of penicillin.4,5 Unfortunately, syphilis has been replaced by HIV infection, a disease that affects more than 25 million people in Africa. HIV‐related cardiac pathology, which manifests mainly as dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and tuberculous pericarditis, has emerged as an important cause of heart failure in many African countries.26,27

This review deals with the contemporary trends in the epidemiology and management of cardiomyopathies and pericarditis in sub‐Saharan Africa. The impact of HIV infection on the clinical epidemiology of cardiomyopathy and pericarditis is also examined. The implications of these new developments for clinical practice and research are summarised.

Endemic cardiomyopathies

DCM, PCM and EMF are endemic in sub‐Saharan Africa.3 DCM is a disease that is found in all age groups and in all the regions of Africa. By contrast, EMF is a disease of children and young adults, which is confined to the tropical regions of equatorial Africa.

Dilated cardiomyopathy

DCM, a primary disorder of heart muscle, which is characterised by dilatation and impaired contraction of the chambers of the heart, accounts for 10–17% of cardiac conditions encountered at necropsy,28 and for 20% of patients who are admitted to hospital for heart failure (fig 1). Presentation is usually with heart failure, which is progressive, with a 4 year mortality of 34% after the onset of symptoms.29 DCM represents a final common expression of myocardial damage that can be provoked by multiple insults, including haemodynamic, infective, immunological, toxic, nutritional and genetic factors. The aetiological factors that have been examined in African subjects include unrecognised hypertension, myocarditis, autoimmune mechanisms, iron overload, excessive alcohol intake, nutritional deficiency and pregnancy. A systematic overview of studies of these potential aetiological factors is available elsewhere.3

It has been established that an intensive strategy of clinical investigation which includes coronary angiography and endomyocardial biopsy, where indicated, yields a specific diagnosis in up to 50% of patients with previously unexplained DCM.29 The cases of DCM that remain unexplained even after invasive investigation need to be considered for family and molecular genetic studies. A major advance in the study of the pathogenesis of unexplained DCM has been the demonstration that about 30% of cases are familial, suggesting that genetic factors may be involved in the aetiology of the condition.30 Reported families most commonly are compatible with autosomal dominant inheritance, but some with X‐linked and autosomal recessive inheritance have been documented. Familial DCM is caused by mutations at over 25 chromosome loci, where genes encoding contractile, cytoskeletal and calcium regulatory proteins have been identified, underlining the genetic heterogeneity of the condition.31

To the best of our knowledge, the first report of familial DCM in Africa described twin brothers who were affected from Uganda.32 Brink et al subsequently documented a condition characterised by hereditary dysrhythmic congestive cardiomyopathy,33 and Przybojewski et al described two brothers of Afrikaner ancestry with unexplained DCM from South Africa.34 More recently, Fernandez and others have shown that familial progressive heart block type II, which was initially reported in 1977, may be associated with DCM in the late stages of the disease.35,36

Apart from these reports, there seem to be no systematic family studies that have been conducted to establish the frequency of familial DCM in Africans,3 such as have been done elsewhere.37 Nevertheless, several gene association studies have been conducted, which suggest that heredity may have a role in the susceptibility to DCM in Africans. An association with HLA‐DR1 and DRw10 antigens has been reported in South African patients, implying that genetically determined immune‐response factors have a role in the pathogenesis of some people with DCM.38 A common mitochondrial DNA polymorphism (T16189C) has also been found to be a genetic risk factor for DCM in a South African cohort, with a population attributable risk of 6%.39 These genetic associations have been replicated in other populations, suggesting that they may represent genuine genetic risk factors for DCM world wide.40,41 Mutation screening studies in South African patients with idiopathic and familial DCM have identified a family with early onset DCM caused by a known mutation in the troponin T gene (Arg141Trp),42 but failed to show mutations in the cardiac and skeletal actin genes.43

The management of African patients with heart failure due to DCM is similar to that for patients with other forms of heart failure.44 There is, however, emerging clinical trial evidence from South Africa that suggests that the immunomodulating agent, pentoxifylline, may be beneficial in patients with heart failure due to cardiomyopathy.45,46 The rationale for the use of this agent is based on some serological and histological evidence of abnormal immune activation and myocarditis as potential aetiological factor in DCM in Africans.47,48 These preliminary studies indicate that pentoxifylline use may be associated with an improvement in effort tolerance, left ventricular function and a trend towards lower mortality in patients receiving standard treatment for heart failure.3 A recent systematic review has, however, highlighted the limitations of the available evidence on the effectiveness of pentoxifylline in the treatment of heart failure.49 The existing trials are small (with a total of 144 randomised participants) and do not provide conclusive estimates of the effect of pentoxifylline on important clinical outcomes, such as mortality. The promising results that have been obtained with pentoxifylline in the treatment of heart failure due to cardiomyopathy need to be tested in large multicentre randomised trials with the power to determine mortality benefits.3

Peripartum cardiomyopathy

PCM, which is defined as a disorder of unknown cause in which left ventricular systolic dysfunction and symptoms of heart failure occur between the last month of pregnancy and the first 5 months postpartum,3,21 shares many features with other forms of non‐ischaemic DCM. The important distinction is that women with PCM have a higher rate of spontaneous recovery of ventricular function and better survival than idiopathic DCM.29,50 A prospective echocardiographic study of 92 women from Haiti showed partial improvement of systolic function in the first year in the majority of patients, with one‐third of patients recovering fully over 3–5 years.51 The contemporary mortality rate is 15% at 6 months,52 and 42% over 25 years of follow‐up.53 The clinical predictors of mortality are New York Heart Association functional class at presentation, radiographic cardiothoracic ratio, ECG QRS voltage based on the Sokolow–Lyon criteria and higher diastolic blood pressure.52,53 The presence of HIV infection does not seem to have an effect on outcome at 6 months of follow‐up.54

The epidemiology, aetiology, clinical profile, and management of PCM has been reviewed in detail elsewhere.3,21 Although PCM is reported in some form in all parts of the sub‐Saharan region in about 1 per 1500 deliveries, the Zaria province of Nigeria is a hot spot for a unique form of the disease that affects 1 in every 100 women after delivery. This phenomenon is presumed to be due to volume overload as a consequence of ingestion of kanwa, a dried lake salt, while lying on heated mud beds twice daily for 40 days post partum.55

An important advance in this field has been the intriguing discovery of the possible role of excessive prolactin production in the pathogenesis of PCM in mice and women.56,57 A high incidence of PCM has been discovered in mice with a knockout of the cardiac‐tissue‐specific signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), a DNA binding protein that is activated by interleukin‐6. STAT3, in addition to mediating cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and myocardial angiogenesis, also protects the heart from oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidative enzymes such as superoxide desmutatse. A reduction in STAT3 leads to increased oxidative stress, activation of cathepsin D, which leads to the cleavage of prolactin into an antiangiogenic and proapoptotic 16 kDa isoform.56 The treatment of stat3‐deficient mice with the inhibitor of prolactin secretion, bromocriptine, prevents the development of PCM. A study of patients with PCM shows that STAT3 protein levels are reduced in the heart, serum levels of activated cardiac cathepsin D and 16 kDa prolactin are increased, raising the possibility that the biologically active derivative of prolactin may mediate PCM in humans.

A preliminary clinical trial of 12 women who had recovered from a previous episode of PCM and presented with a subsequent pregnancy, in which six out of the 12 women received bromocriptine in addition to standard treatment up for to 3 months after delivery while six patients received standard treatment, has shown promising results.56 In patients receiving bromocriptine after delivery, serum prolactin levels, which were raised more than fivefold, returned to non‐pregnant levels within 14 days of treatment. Three months post partum, all six bromocriptine‐treated women had preserved or increased left ventricular function and dimensions and survived the 4‐month observation period. By contrast, the ejection fraction in the non‐bromocriptine‐treated group deteriorated and three women had died within 4 months. These intriguing and consistent human and mouse data provide a sound justification for assessing the effectiveness of bromocriptine in the treatment of PCM in a large randomised controlled trial with the important clinical end points.

Endomyocardial fibrosis

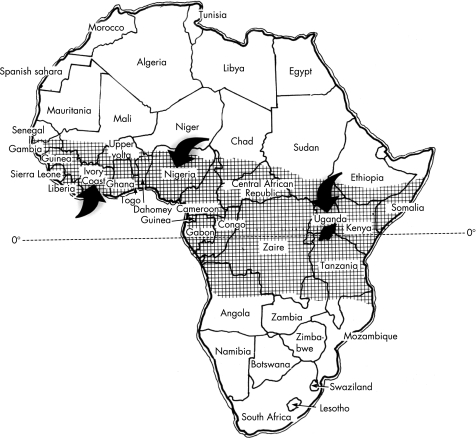

EMF is a form of restrictive cardiomyopathy, in which dense fibrosis in the mural endocardium restricts ventricular diastole and entraps the papillary muscles of the atrioventricular valves. EMF, which occurs mainly in tropical and subtropical areas, is probably the commonest cause of restrictive cardiomyopathy in the world. In Africa, the first modern description of EMF is ascribable to Williams in Uganda.58 The disorder was named endomyocardial fibrosis in a subsequent clinicopathological study,59 and was given the eponym, Davies' disease,60,61 in deference to the seminal contributions of Davies.62 EMF has been reported in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, Gabon, Congo, Cameroon, Sudan, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Ghana (fig 2). It is uncommon in northern and southern Africa. EMF in Africa is more commonly right sided or bilateral, and rarely left sided. The disease predominates in children and young adults, with a peak incidence between the ages of 11 and 15 in both sexes.

Figure 2 Geographical distribution of endomyocardial fibrosis in Africa is shown in the shaded area. Arrows indicate the location of major centres of research in this disease. Zaire is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. Reproduced with permission of Professor Krishna Somers, Perth, Australia.

EMF is said to be the most common form of heart disease in Ugandan hospitals, where it accounts for nearly 20% of cases referred to an echocardiography service.63 The only population‐based epidemiological survey performed in Africa was based on an echocardiographic diagnosis of EMF in the Inharrime district of Mozambique. In a sample of 948 inhabitants from an endemic area and aged between 4 and 45 years, a prevalence of 8.9% was found, suggesting that EMF is a major form of heart disease in the region.64,65

The clinical features of EMF depend on the stage of the disease and the anatomical involvement of the heart. An initial illness with fever, chills, night sweats, facial swelling and urticaria is reported by 30–50% of children and adolescents.66 A retrospective history of fever in malaria‐prone areas is a confounding fact. In natural history there may be rapidly developing cardiac failure and early death, or evolution to established and apparently inactive EMF with predominantly right ventricular or left ventricular disease. Ascites with little or no peripheral oedema is the characteristic clinical feature of end‐stage EMF, regardless of which ventricle is affected. Unlike congestive right heart failure, the ascites is an exudate in 75% of cases and is associated with peritoneal fibrosis.67 An exudative pericardial effusion of variable size is a common presentation. Several environmental (geography, social deprivation, infection) and host (diet, ethnicity, eosinophilia) factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of EMF in Africa. Although in Uganda the disease is said to be more common among immigrants from neighbouring Rwanda and Burundi who have settled in specific geographical districts of the country,60,61,68 EMF also occurs in other Ugandans and in foreigners who have lived in tropical Africa,69,70 suggesting that the disease cannot be explained solely by ethnic factors or social deprivation.

Eosinophilia has also been proposed as a major risk factor for EMF in both Uganda and Nigeria.68,71 The level of eosinophilia has been found to be inversely related to the duration of illness, leading to the notion that patients who do not have eosinophilia are at a late stage of EMF. The usual presentation of EMF is in end‐stage restrictive cardiomyopathy. There has been a suggestion that Loeffler's endocarditis, which is occasionally seen in non‐tropical countries, and EMF represent the extremes of the same disease. Eosinophils contain major basic protein, cationic protein, protein X and other substances which are released during degranulation and which are thought to be toxic to the endo‐ and myocardium, resulting in mural thrombosis and fibrosis.72

The pathogenesis of EMF remains elusive. It appears, however, that the conditioning factor is geography and socioeconomic status, the triggering factor may be an as yet unidentified infective agent, and the perpetuating factor may be eosinophilia. Apart from a few isolated reports of familial cases of EMF in endemic regions,73,74 the role of familial and genetic factors has not been studied systematically in this condition.3

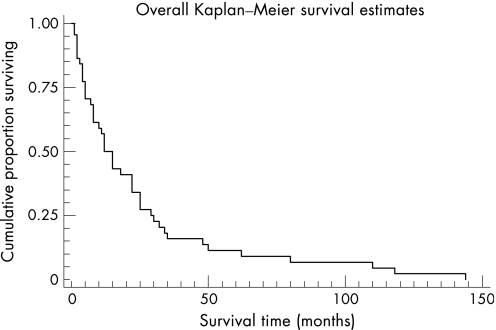

Although controlled trials are not available, there is a belief that corticosteroids and immunosuppressant agents may have a role in the early illness of EMF, especially in patients with hypereosinophilia.66 Standard treatment with diuretics and cardiac glycosides has little effect, except in those with pulmonary venous congestion. Paracentesis may be required to relieve ascites, but this causes significant protein loss and the fluid reaccumulates quickly. Response to medical treatment for heart failure is generally poor, with a 75% mortality rate at 2 years after the onset of symptoms (fig 3).22

Figure 3 Survival of 46 patients with endomyocardial fibrosis after the first symptoms (data source: D'Arbela et al22). Reprinted with permission from Mayosi BM, Somers K. Cardiomyopathy in Africa: heredity versus environment. Cardiovasc J S Afr 2007;18:175–9.110

Tailored surgical excision of fibrotic endocardial material and reconstruction of the atrioventricular valve or valve replacement releases the myocardium, increasing ventricular volume and improving contractile function. The determinants of a good outcome appear to be intervention in the earlier stages of the disease before extensive fibrosis, muscle thinning, valvular destruction, left ventricular dysfunction and mural calcification have set in.75 Surgery is recommended for selected patients with heart failure due to EMF as it is their only hope of survival; the actuarial probability of survival at 17 years, including operative mortality, may be as high as 55%, indicating that surgery should be considered in all cases where feasible.76

Non‐endemic cardiomyopathies

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which was found in 0.2% of 6680 unselected echocardiograms in Tanzania,77 is recognised in Africans and other populations as an autosomal dominant disorder that is caused by mutations in at least 11 different genes that code for sarcomeric proteins.3 Most HCM‐causing mutations have arisen independently in most families studied, suggesting that the majority occurred relatively recently as new mutations.30 This finding predicts that HCM is likely to be evenly distributed among different populations world wide.78 Experience elsewhere in the world has disclosed numerous mutations in the sarcomeric protein genes, such that many families have a “private” mutation.30 In South Africa, however, there are three founder mutations that recur in 45% of genotyped patients of Afrikaner and mixed racial ancestry.79 Consequently, South African patients of Afrikaner or mixed ancestry with HCM referred for molecular diagnosis are initially screened for the three founder mutations (ie, β‐MHC Arg403Trp, β‐MHC Ala797Thr, and cTNT Arg92Trp), and more extensive screening is performed only in their absence.30

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) was reported for the first time in Africa in 2000,80 about 40 years after the first case was described.81 The disease is known to be familial in about half of affected patients. Initial information from the newly established ARVC Registry of South Africa suggests that the disease occurs in all segments of the population, and that its clinical features, frequency of familial disease and outcome are similar to experience that has been gathered elsewhere in the world.3

HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy

The association of HIV infection with cardiomyopathy was recognised in the early stages of the HIV epidemic.82 Although the percentage of people living with HIV who develop clinically apparent cardiomyopathy is relatively small, the disease burden could be substantial in the face of the exceptionally high prevalence of HIV infection in sub‐Saharan Africa.26 The fact that HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy has a poor prognosis, with progression to death within 100 days of diagnosis in patients who are not treated with antiretroviral drugs,26 and as the vast majority of patients with HIV in this continent do not yet have access to antiretroviral therapy, HIV‐associated heart muscle disease has the potential to result in a heavy burden of patients with heart failure with a very poor prognosis in Africa.

Cross‐sectional and retrospective studies suggest that myocardial dysfunction is a common abnormality, among other systemic and protean manifestations of immunosuppression, in acutely ill hospitalised patients with HIV in Africa.83 A prospective echocardiographic study of acutely ill, hospitalised patients showed that of the 50% of patients who had a cardiac abnormality, 31% had left ventricular dysfunction (22%) or cardiomyopathy (9%) and 19% had pericardial effusion.83 HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy is characterised by global systolic functional impairment with or without left ventricular dilatation. The prevalence of cardiomyopathy in non‐hospitalised ambulant HIV positive patients ranges from 15% to 17%,84,85 a rate that is similar to Western series.86 The association of cardiomyopathy with more advanced immunosuppression and lower CD4 counts that was found in the African series is consistent with international experience.27,85

Few studies have examined the cause of cardiomyopathy in HIV‐infected people living in Africa.26 Systematic reviews of the literature identified one report of cardiac histology in 16 HIV‐positive patients with cardiomyopathy in a cohort of 157 patients.27,87 All 16 patients had histopathological changes of acute myocarditis. It was not stated in that report whether these data were acquired from ante mortem or postmortem samples. Myocarditis was attributed to Toxoplasmagondii in 3/16 cases (18.75%), to Cryptococcus neoformans in 3/16 cases (18.75%), to Mycobacterium avium intracellulare in 2/16 cases (12.5%), and to direct HIV infection in 8/16 (50%) patients. These preliminary data suggest that HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy may be caused by potentially treatable opportunistic infections in up to 50% of patients living in the Democratic Republic of Congo. By contrast, in Western series, opportunistic cardiotropic viral infections have been implicated in a significant proportion of cases.26

Standard treatment for heart failure is indicated in the management of patients with HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy. There has been a significant reduction of HIV‐associated cardiomyopathy in the highly active anti‐retroviral therapy (HAART) era.27 There is no conclusive evidence that HAART reverses cardiomyopathy, but it appears that by preventing profound immunosuppression and the development of AIDS, the heart muscle remains healthier for longer.88

Pericarditis

Tuberculosis is the most common cause of pericarditis in Africa, Asia and other regions where tuberculosis remains a major public health problem.25 In one series from the Western Cape Province of South Africa, tuberculous pericarditis accounted for 70% of cases of large pericardial effusion.89 Table 1 compares the causes of large pericardial effusion in the largest contemporary series of pericarditis in an African and Italian institution.90,91 The causes of pericarditis in the Western series is dominated by idiopathic cases, which has been the case for over 20 years.92,93 By contrast, in tuberculosis‐endemic regions, which affect the majority of the world's population, tuberculosis is the leading cause of pericardial effusion. The non‐tuberculous causes of effusion account for a significant third of cases, and these are associated with a poorer prognosis than a tuberculous aetiology.94,95

Table 1 Causes of large pericardial effusion in contemporary African and non‐African case series.

| Causes | Reuter et al, 200690 (n = 233) | Imazio et al, 200791 (n = 453) |

|---|---|---|

| Period of study | 1995–2001 | 1996–2004 |

| Tuberculous pericarditis | 162 (69.5) | 17 (3.8) |

| Neoplastic pericarditis | 22 (9.4) | 23 (5.1) |

| Connective tissue disease or autoimmune aetiology | 12 (5.2) | 33 (7.3) |

| Purulent/septic pericarditis | 5 (2.1) | 3 (0.7) |

| Idiopathic or other causes | 32 (13.7) | 377 (83.2) |

Data are shown as number (%).

Tuberculous pericarditis is a common cause of heart failure in sub‐Saharan Africa, being less common than rheumatic heart disease and more common than hypertensive heart disease and cardiomyopathy in the Eastern Cape of South Africa and Zimbabwe.96,97 Echocardiography studies of the relative importance of aetiologies for heart failure in African subjects indicate that tuberculous pericarditis accounts for 8–13% of cases in South Africa and Kenya, and 3% overall in the sub‐Saharan region (fig 1).5,12

The pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of tuberculous pericarditis has been reviewed extensively elsewhere.25,98 This paper will review the clinical epidemiology of HIV‐associated pericarditis, a syndrome with unique clinical features and poor prognosis.

HIV‐associated pericarditis

The incidence of pericarditis in sub‐Saharan Africa is increasing as a result of the HIV epidemic.99,100 Tuberculosis is the cause of large pericardial effusion in over 90% of HIV‐infected patients who live in tuberculosis‐endemic regions and communities89,100,101; by contrast, non‐HIV infected subjects have other aetiologies for the pericardial effusion in 30–50% of cases.89,101 A multicentre prospective study that recruited patients with suspected tuberculous pericarditis from centres in Cameroon, Nigeria and South Africa showed marked regional variation in the prevalence of HIV‐associated pericarditis, with an average of about 50% of patients with presumed tuberculous pericarditis having clinical or serological markers of HIV infection.102

Since the early 1980s, HIV infection has emerged as the most important predisposing factor to tuberculosis, raising the risk by 20 times overall, and by 120 times in the face of AIDS.103 HIV‐associated tuberculosis is more often atypical, extrapulmonary, multisite, widely disseminated, invasive and associated with tuberculous bacteraemia. There is an increased risk of reactivation and reinfection with HIV infection. In Malawi, pericardial tuberculous effusion is the second most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, second only to pleural disease, and the HIV seroprevalence is greater in patients with tuberculous pericardial effusion (92%) than in patients with severe (86%) and non‐severe (72%) forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Recent data suggest that the histological pattern may be affected by the immune status of the patient, with fewer granulomas being observed in HIV‐infected patients with severely depleted CD4 lymphocytes.104

Clinical presentation

The effect of HIV co‐infection on clinical features of pericarditis has been studied in the Investigation of the Management of Pericarditis in Africa (IMPI Africa) registry of 185 patients with suspected tuberculous pericarditis from Cameroon, Nigeria and South Africa.102 Forty per cent of patients (n = 74) enrolled in this study had clinical features of HIV infection. Patients with clinical HIV disease were more likely to present with dyspnoea and electrocardiographic features of myopericarditis. A positive HIV serological status was associated with greater cardiomegaly and haemodynamic instability. Patients with HIV were also less likely to present with abdominal swelling and ascites and more likely to have an effusion on echocardiography, suggesting a lower incidence of effusive‐constrictive disease.

Outcome

HIV infection appears not to impair the initial response to tuberculous treatment but may be associated with a higher risk of relapse or, possibly, reinfection.105 A single‐centre study has shown that the 30‐day and 1‐year mortality for HIV positive patients is 10% and 22% compared with 6% and 12% in HIV negative cases with definite tuberculous pericarditis.94 The higher mortality in association with HIV infection has been confirmed in the pan‐African multicentre prospective study of 185 patients, which showed an average mortality rate of 26% at 6 months, increasing to 40% in patients with AIDS.95 There is an urgent need for the development of more effective antituberculosis treatments to reduce the high morbidity and mortality associated with tuberculous pericarditis in the HIV era.

Management

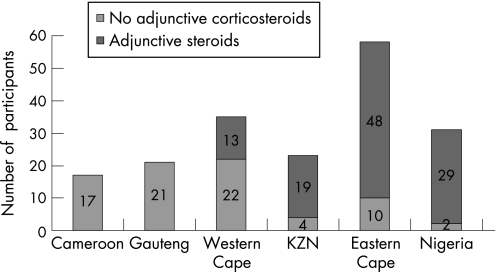

There is uncertainty about the effectiveness of adjunctive corticosteroids in reducing mortality in tuberculous pericarditis.106 Furthermore, there is concern about the safety of adjunctive corticosteroids in HIV‐infected patients because of the potential increase in adverse effects in immunocompromised hosts107; a randomised controlled trial of the use of prednisolone as an adjunct to treatment in HIV‐1‐associated pleural tuberculosis showed no survival benefit, but a significant increase of Kaposi sarcoma in HIV‐infected patients treated with steroids.108 To assess the impact of this uncertainty about effectiveness and safety on contemporary clinical practice, we studied the use of adjunctive corticosteroid in 185 consecutive patients with suspected pericardial tuberculosis from 15 hospitals in Cameroon, Nigeria and South Africa. One hundred and nine (58.9%) patients received steroids with significant variation in corticosteroid use, ranging from 0% to 93.5% per centre (fig 4). The presence of clinical features of HIV infection was an independent predictor of the non‐use of adjunctive corticosteroids.109

Figure 4 Regional distribution of adjunctive steroid use in sub‐Saharan Africa: Yaoundé, Cameroon (0%); Guateng, South Africa (0%); Western Cape, South Africa (37.1%); KwaZulu Natal (KZN), South Africa (82.6%); Eastern Cape, South Africa (82.8%); Ibadan, Nigeria (93.5%).

There is marked variation in the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in tuberculous pericarditis by practitioners, with nearly half of all patients not receiving this intervention. Taken together with the statistical uncertainty about the effectiveness of adjunctive steroids in tuberculous pericarditis, these observations probably reflect a state of genuine uncertainty or clinical equipoise among practitioners who care for patients with tuberculous pericarditis in sub‐Saharan Africa.109 These data provide a justification for the establishment of adequately powered randomised clinical trials to assess the effectiveness of adjunctive corticosteroids in patients with tuberculous pericarditis.25

Conclusion

This paper reports the unique features, new knowledge, controversies and unanswered questions on the epidemiology and management of cardiomyopathy and pericarditis in sub‐Saharan Africa (table 2).

Table 2 Summary of the main points, new knowledge, controversies and unanswered questions in cardiomyopathy and pericarditis in sub‐Saharan Africa.

| Summary of the main points |

| • In sub‐Saharan Africa, heart failure is largely a non‐ischaemic disease of the young and middle‐aged adults, which is caused mainly by hypertension, rheumatic heart disease and cardiomyopathy. |

| • Dilated and peripartum cardiomyopathies, and endomyocardial fibrosis, which are endemic in sub‐Saharan Africa, account for 20% of all cases of heart failure. |

| • Endomyocardial fibrosis is a major form of heart disease that is found in 9% of the general population in affected regions of Mozambique. Early surgery is the only intervention that may reduce morbidity and improve survival in symptomatic cases with endomyocardial fibrosis. |

| • Apart from a founder effect for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the Afrikaner and mixed ancestry population of South Africa, the epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy is similar to that of other populations of the world. |

| • HIV infection is associated with an increase in the incidence of cardiomyopathy and tuberculous pericarditis, both of which are associated with poor prognosis without antiretroviral drug treatment. |

| New knowledge |

| • A stat‐3‐deficient mouse model develops peripartum cardiomyopathy owing to excessive production of an abnormal prolactin isoform that causes cardiomyopathy. The prolactin antagonist, bromocriptine, reverses the heart failure in the mouse model. A small clinical trial of 12 African patients with peripartum cardiomyopathy shows the same abnormalities of STAT3 and abnormal prolactin production, with a good response to bromocriptine treatment. |

| • HIV‐associated tuberculous pericarditis is associated with a severe myopericardial disease and mortality of up to 40% at 6 months despite antituberculous treatment. |

| Unanswered questions and controversies |

| • There is a need for population‐based studies of the incidence, prevalence and aetiology of heart failure in Africa. |

| • The role (if any) of genetic factors in peripartum cardiomyopathy and endomyocardial fibrosis remains unknown. |

| • The effectiveness of pentoxifylline in heart failure due to cardiomyopathy, and bromocriptine in peripartum cardiomyopathy, remains to be established in adequately powered randomised trials with important clinical end points. |

| • It remains to be established whether the early detection of endomyocardial fibrosis and the institution of surgery before end‐stage disease will prevent morbidity and mortality in this condition. |

| • The effectiveness of adjunctive oral corticosteroids in reducing progression to constriction and mortality in tuberculous pericarditis, and safety in patients who are immunosuppressed by HIV, needs to be established in adequately powered randomised trials with important clinical end points. |

In Africa, there is a need for renewed focus on the assessment and control of the non‐ischaemic causes of heart failure, in addition to measures to prevent the rise of risk factors that will lead to degenerative atherosclerotic disease in the future.16 Sub‐Saharan Africa is the only region of the world where non‐ischaemic causes of circulatory disease are still dominant, and where risk factors for atherosclerotic disease are still relatively low. The continent provides a historic opportunity for primordial prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded, in part, by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, the National Research Foundation of South Africa and the Wellcome Trust (UK).

Abbreviations

DCM - dilated cardiomyopathy

EMF - endomyocardial fibrosis

HCM - hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

PCM - peripartum cardiomyopathy

STAT3 - signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Bedford D E, Konstam G L S. Heart failure of unknown aetiology in Africans. Br Heart J 19468236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendez G F, Cowie M R. The epidemiological features of heart failure in developing countries: a review of the literature. Int J Cardiol 200180213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sliwa K, Damasceno A, Mayosi B M. Epidemiology and etiology of cardiomyopathy in Africa. Circulation 20051123577–3583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antony K K. Pattern of cardiac failure in Northern Savanna Nigeria. Trop Geogr Med 198032118–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyoo G O, Ogola E N. Clinical and socio demographic aspects of congestive heart failure patients at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J 19997623–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelfand M.The sick African. 2nd ed. Cape Town: Juta, 1957

- 7.Schwartz M B, Schamroth L, Seftel H C. The pattern of heart disease in the urbanized (Johannesburg) African. Med Proc 19584275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaper A G, Williams A W. Cardiovascular disorders at an African hospital in Uganda. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 19605412–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosnett J E. Heart disease in the Zulu: especially cardiomyopathy and cardiac infarction. Br Heart J 19622476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldachin B J. Cardiovascular disease in the African in Matabeleland. Cent Afr J Med 196328463–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell S J, Wright R. Cardiomyopathy in Durban. S Afr Med J 1965391062–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maharaj B. Causes of congestive heart failure in black patients at King Edward VIII Hospital, Durban. Cardiovasc J S Afr 1991231–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thiam M. Cardiac insufficiency in the African cardiology milieu. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 200396217–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingue S, Dzudie A, Menanga A.et al [A new look at adult chronic heart failure in Africa in the age of the Doppler echocardiography: experience of the medicine department at Yaounde General Hospital]. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 200554276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amoah A G, Kallen C. Aetiology of heart failure as seen from a national cardiac referral centre in Africa. Cardiology 20009311–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Commerford P, Mayosi B. An appropriate research agenda for heart disease in Africa. Lancet 20063671884–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swai A B M, Mclarty D G, Kitange H M.et al Low prevalence of risk factors for coronary heart disease in rural Tanzania. Int J Epidemiol 199322651–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gebre‐Yohannes A, Rahlenbeck S I. Coronary heart disease risk factors among blood donors in northwest Ethiopia. East Afr Med J 199875495–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okesina A B, Oparinde D P, Akindoyin K A.et al Prevalence of some risk factors of coronary heart disease in a rural Nigerian population. East Afr Med J 199976212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox K F, Cowie M R, Wood D A.et al Coronary artery disease as the cause of incident heart failure in the population. Eur Heart J 200122228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sliwa K, Fett J, Elkayam U. Peripartum cardiomyopathy. Lancet 2006368687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Arbela P G, Mutazindwa T, Patel A K.et al Survival after first presentation with endomyocardial fibrosis. Br Heart J 197234403–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenger N K. The greying of cardiology: implications for management. Heart 200793411–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg R J, Ciampa J, Lessard D.et al Long‐term survival after heart failure: a contemporary population‐based perspective. Arch Intern Med 2007167490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayosi B M, Burgess L J, Doubell A F. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation 20051123608–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magula N P, Mayosi B M. Cardiac involvement in HIV‐infected people living in Africa: a review. Cardiovasc J S Afr 200314231–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ntsekhe M, Hakim J. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection on cardiovascular disease in Africa. Circulation 20051123602–3607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallichurum S. Major aetiological types of heart failure in the Bantu in Durban. S Afr Med J 196943250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felker G M, Thompson R E, Hare J M.et al Underlying causes and long‐term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 20003421077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moolman‐Smook J C, Mayosi B M, Brink P A.et al Molecular genetics of cardiomyopathy: changing times, shifting paradigms. Cardiovasc J S Afr 200314145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad F, Seidman J G, Seidman C E. The genetic basis for cardiac remodeling. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 20056185–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ower R, Rwomushana R J W. Familial congestive cardiomyopathy in Uganda. East Afr Med J 197552372–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brink A J, Torrington M, van der Walt J J. Hereditary dysrhythmic congestive cardiomyopathy. S Afr Med J 1976502119–2123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Przybojewski J Z, van der Walt J J, van Eeden P J.et al Familial dilated (congestive) cardiomyopathy. Occurrence in two brothers and an overview of the literature. S Afr Med J 19846626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brink A J, Torrington M. Progressive familial heart block – two types. S Afr Med J 19775253–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez P, Moolman‐Smook J, Brink P.et al A gene locus for progressive familial heart block type II (PFHBII) maps to chromosome 1q32.2–q32.3. Hum Genet 20051181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michels V V, Moll P P, Miller F A.et al The frequency of familial dilated cardiomyopathy in a series of patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 199232677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maharaj B, Hammond M G. HLA‐A, B, DR, and DQ antigens in black patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1990651402–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khogali S S, Mayosi B M, Beattie J M.et al A common mitochondrial DNA variant associated with susceptibility to dilated cardiomyopathy in two different populations. Lancet 20013571265–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez‐Perez J M, Fragoso J M, Alvarez‐Leon E.et al MHC class II genes in Mexican patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Exp Mol Pathol 20078249–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marin‐Garcia J, Zoubenko O, Goldenthal M J. Mutations in the cardiac mitochondrial DNA control region associated with cardiomyopathy and aging. J Card Fail 2002893–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayosi B M, Meissenheimer L, Matolweni L O.et al A cardiac troponin T gene mutation causes early‐onset familial dilated cardiomyopathy in a South African family. Cardiovasc J S Afr 200415237 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayosi B M, Khogali S, Zhang B.et al Cardiac and skeletal actin gene mutations are not a common cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet 199936796–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med 20033482007–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sliwa K, Skudicky D, Candy G.et al Effects of pentoxifylline on the left ventricular performance in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Lancet 19983511091–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sliwa K, Woodiwiss A, Candy G.et al Pentoxifylline modifies cytokine profiles and improves left ventricular performance in patients with decompensated congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2002901118–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanderson J E, Olsen E G, Gatei D. Peripartum heart disease: an endomyocardial biopsy study. Br Heart J 198656285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanderson J E, Olsen E G, Gatei D. Dilated cardiomyopathy and myocarditis in Kenya: an endomyocardial biopsy study. Int J Cardiol 199341157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batchelder K, Mayosi B M. Pentoxifylline for heart failure: a systematic review. S Afr Med J 200595171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Hoeven K H, Kitsis R N, Katz S D.et al Peripartum versus idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy in young women – a comparison of clinical, pathologic and prognostic features. Int J Cardiol 19934057–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fett J D, Christie L G, Carraway R D.et al Five‐year prospective study of the incidence and prognosis of peripartum cardiomyopathy at a single institution. Mayo Clin Proc 2005801602–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sliwa K, Forster O, Libhaber E.et al Peripartum cardiomyopathy: inflammatory markers as predictors of outcome in 100 prospectively studied patients. Eur Heart J 200627441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ford L, Abdullahi A, Anjorin F.et al The outcome of peripartum cardiac failure in Zaria, Nigeria. QJM 19989193–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forster O, Ansari A A, Sundstrom J B.et al Untreated human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) ‐ infection does not influence outcome in peripartum cardiomyopathy patients [abstract]. Eur Heart J 20062760 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fillmore S J, Parry E O. The evolution of peripartal heart failure in Zaria. Circulation 1977561058–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hilfiker‐Kleiner D, Kaminski K, Podewski E.et al A cathepsin D‐cleaved 16 kDa form of prolactin mediates postpartum cardiomyopathy. Cell 2007128589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leinwand L A. Molecular events underlying pregnancy‐induced cardiomyopathy. Cell 2007128437–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams A W. Heart disease in the native population of Uganda. East Afr Med J 193815229 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ball J D, Williams A W, Davies J N P. Endomyocardial fibrosis. Lancet 195411049–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Connor D H, Somers K, Hutt M S.et al Endomyocardial fibrosis in Uganda (Davies' disease). 1. An epidemiologic, clinical, and pathologic study. Am Heart J 196774687–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Connor D H, Somers K, Hutt M S.et al Endomyocardial fibrosis in Uganda (Davies' disease). II. An epidemiologic, clinical, and pathologic study. Am Heart J 196875107–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davies J N P. Endomyocardial fibrosis: a heart disease of obscure aetiology in Africans. E Afr Med J 19482510–16. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freers J, Mayanja‐Kizza H, Ziegler J L.et al Echocardiographic diagnosis of heart disease in Uganda. Trop Doct 199626125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferreira B, Matsika‐Claquin M, Hausse‐Mocumbi A.et al Geographic origin of endomyocardial fibrosis treated at the central hospital of Maputo (Mozambique) between 1987 and 1999. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 200295276–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marijon E, Ou P. What do we know about endomyocardial fibrosis in children of Africa? Ped Cardiol 200627523–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Freers J, Hakim J, Myanja‐Kizza H.et al The heart. In: Parry E, Godfrey R, Mabey D, et al eds. Principles of medicine in Africa. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004837–886.

- 67.Freers J, Masembe V, Schmauz R.et al Endomyocardial fibrosis syndrome in Uganda. Lancet 20003551994–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rutakingirwa M, Ziegler J L, Newton R.et al Poverty and eosinophilia are risk factors for endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) in Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 19994229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brockington I F, Olsen E G J, Goodwin J F. Endomyocardial fibrosis in Europeans resident in tropical Africa. Lancet 1967i583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beck W, Schrire V. Endomyocardial fibrosis in Caucasians previously resident in tropical Africa. Br Heart J 197234915–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andy J J, Ogunowo P O, Akpan N A.et al Helminth associated hypereosinophilia and tropical endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) in Nigeria. Acta Tropica 199869127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tai P C, Ackerman S J, Spry C J.et al Deposits of eosinophil granule proteins in cardiac tissues of patients with eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Lancet 1987i643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Adi F C. Endomyocardial fibrosis in two brothers. Br Heart J 196325684–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Patel A K, Ziegler J L, D'Arbela P G.et al Familial cases of endomyocardial fibrosis in Uganda. BMJ 197148331–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mocumbi A O, Sidi D, Vouhe P.et al Pathophysiology of the right ventricular obliteration in endomyocardial fibrosis: implications for its surgical relief. J Thorac Cardiavasc Surg (in press)

- 76.Moraes F, Lapa C, Hazin S.et al Surgery for endomyocardial fibrosis revisited. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 199915309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Maro E E, Janabi M, Kaushik R. Clinical and echocardiographic study of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in Tanzania. Trop Doct 200636225–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mayosi B M, Watkins H. Impact of molecular genetics on clinical cardiology. J R Coll Physicians Lond 199933124–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moolman‐Smook J C, De Lange W J, Bruwer E C.et al The origins of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy‐causing mutations in two South African subpopulations: a unique profile of both independent and founder events. Am J Hum Genet 1999651308–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Munclinger M J, Patel J J, Mitha A S. Follow‐up of patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy dysplasia. S Afr Med J 20009061–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dalla Volta S, Battaglia G, Zerbini E. “Auricularization” on the right ventricular pressure curve. Am Heart J 19616125–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cohen I S, Anderson D W, Virmani R.et al Congestive cardiomyopathy in association with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1986315628–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hakim J G, Matenga J A, Siziya S. Myocardial dysfunction in human immunodeficiency virus infection: an echocardiographic study of 157 patients in hospital in Zimbabwe. Heart 199676161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nzuobontane D, Blackett K N, Kuaban C. Cardiac involvement in HIV infected people in Yaoundé, Cameroon. Postgrad Med J 200278678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Twagirumukiza M, Nkeramihigo E, Seminega B.et al Prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy in HIV‐infected African patients not receiving HAART: a multicenter, observational, prospective, cohort study in Rwanda. Curr HIV Res 20075129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Currie P F, Jacob A J, Foreman A R.et al Heart muscle disease related to HIV infection: prognostic implications. BMJ 19943091605–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Longo‐Mbenza B, Seghers K V, Phuati M.et al Heart involvement and HIV infection in African patients: determinants of survival. Int J Cardiol 19986463–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pugliese A, Isnardi D, Saini A.et al Impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV‐positive patients with cardiac involvement. J Infect 200040282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reuter H, Burgess L J, Doubell A F. Epidemiology of pericardial effusions at a large academic hospital in South Africa. Epidemiol Infect 2005133393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reuter H, Burgess L, van Vuuren W.et al Diagnosing tuberculous pericarditis. QJM 200699827–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B.et al Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation 20071152739–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Permanyer‐Miralda G, Sagrista‐Sauleda J, Soler‐Soler J. Primary acute pericardial disease: a prospective series of 231 consecutive patients. Am J Cardiol 198556623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zayas R, Anguita M, Torres F.et al Incidence of specific etiology and role of methods for specific etiologic diagnosis of primary acute pericarditis. Am J Cardiol 199575378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Reuter H, Burgess L J, Louw V J.et al The management of tuberculous pericardial effusion: experience in 233 consecutive patients. Cardiovasc J S Afr 20071820–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wiysonge C S, Ntsekhe M, Gumedze F.et al Excess mortality in presumed tuberculous pericarditis. Eur Heart J 200627958 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strang J I. Tuberculous pericarditis in Transkei. Clin Cardiol 19847667–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hakim J G, Manyemba J. Cardiac disease distribution among patients referred for echocardiography in Harare, Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med 199844140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Syed F F, Mayosi B M. A modern approach to tuberculous pericarditis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Cegielski J P, Ramiya K, Lallinger G J.et al Pericardial disease and human immunodeficiency virus in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Lancet 1990335209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maher D, Harries A D. Tuberculous pericardial effusion: a prospective clinical study in a low‐resource setting—Blantyre, Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19971358–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cegielski J P, Lwakatare J, Dukes C S.et al Tuberculous pericarditis in Tanzanian patients with and without HIV infection. Tuber Lung Dis 199475429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mayosi B M, Wiysonge C S, Ntsekhe M.et al Clinical characteristics and initial management of patients with tuberculous pericarditis in the HIV era: the Investigation of the Management of Pericarditis in Africa (IMPI Africa) registry. BMC Infect Dis 200662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zumla A, Malon P, Henderson J.et al Impact of HIV infection on tuberculosis. Postgrad Med J 200076259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Reuter H, Burgess L J, Schneider J.et al The role of histopathology in establishing the diagnosis of tuberculous pericardial effusions in the presence of HIV. Histopathology 200648295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hawken M, Nunn P, Gathua S.et al Increased recurrence of tuberculosis in HIV‐1‐infected patients in Kenya. Lancet 1993342332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ntsekhe M, Wiysonge C, Volmink J A.et al Adjuvant corticosteroids for tuberculous pericarditis: promising, but not proven. QJM 200396593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elliott A M, Halwiindi B, Bagshawe A.et al Use of prednisolone in the treatment of HIV‐positive tuberculosis patients. Q J Med 199285855–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Elliott A M, Luzze H, Quigley M A.et al A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of the use of prednisolone as an adjunct to treatment in HIV‐1‐associated pleural tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2004190869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wiysonge C S, Ntsekhe M, Gumedze F.et al Contemporary use of adjunctive corticosteroids in tuberculous pericarditis. Int J Cardiol 2007 Apr 17 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Mayosi B M, Somers K. Cardiomyopathy in Africa: heredity versus environment. Cardiovasc J S Afr 200718175–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]