Abstract

Purpose

To study the design and distribution of different organizational solutions regarding the responsibility for and provision of home care for elderly in Swedish municipalities.

Method

Directors of the social welfare services in all Swedish municipalities received a questionnaire about old-age care organization, especially home care services and related activities. Rate of response was 73% (211/289).

Results

Three different organizational models of home care were identified. The models represented different degrees of integration of home care, i.e. health and social aspects of home care were to varying degrees integrated in the same organization. The county councils (i.e. large sub-national political-administrative units) tended to contain clusters of municipalities (smaller sub-national units) with the same organizational characteristics. Thus, municipalities' home care organization followed a county council pattern. In spite of a general tendency for Swedish municipalities to reorganize their activities, only 1% of them had changed their home care services organization in relation to the county council since the reform.

Conclusion

The decentralist intention of the reform—to give actors at the sub-national levels freedom to integrate home care according to varying local circumstances—has resulted in a sub-national inter-organizational network structure at the county council, rather than municipal, level, which is highly inert and difficult to change.

Keywords: care for the elderly, deinstitutionalisation, decentralisation, integrated care, policy

Introduction

Health care and old-age care in the western world are facing demographical and financial challenges [1–3]. An increasing proportion of elderly people in the population, improved conditions of living, and medical technological advances during the 20th century have raised the demands and expectations on the services provided by the health care system [4–6]. Medical advances have made it possible to move health care partly from hospital to primary care, and often directly into patients' private homes [7, 8]. Today both rehabilitation and advanced palliative care can be provided in patients' private homes [9]. The boundary between health care institutions and homes has been displaced and sometimes almost erased.

The transition from hospital to community care is a general international trend [7, 10, 11]. However, the differences are large between countries. Scandinavian countries have a particularly high volume of community services [12]. The deinstitutionalisation of old-age care is part of this pattern. One important aspect of this deinstitutionalisation is an increase in home care [2]. Policy makers in Europe recommend home care and, wherever possible, a reduction in the number of residential homes [13].

Home care consists of two different kinds of activities: home care services and home help services. Home care services means provision of medical treatment by trained medical and nursing personnel (or delegated to home helpers) in patients' private homes. Home help services, on the other hand, entails provision of social services, and involves domestic work and personal services.

Previously, the old-age care structure was similar in many countries: medical care was provided in hospitals and social care in the community. The deinstitutionalisation has raised the expectations of overcoming the traditional problems of integration of medical and social aspects of care. Attempts have been made, and are still in progress, to integrate health and social care in several countries [14–19].

The purpose of integrated care is to provide care without service gaps, fragmentation or lack of cooperation [20]. Ageing is connected with complex and often interrelated problems comprising physical, psychological and social health [21]. This complexity calls for collaboration between and integration of health and social care [20, 21].

Provision of integrated health and social care is advocated by policy makers in Europe [16]. Alaszewski et al. [21] identify three different approaches to integrated care: structure, process, and outcome. Of these, structure will be dealt with here. Structural integration is mainly a matter of organizational structure (e.g. to bring together staff and resources in one single organization under a unified hierarchical structure). Sweden is by some researchers regarded to be among the most advanced countries with respect to structural integration, mainly due to the introduction of a major organizational reform in 1992 [22, 23].

The Swedish public sector consists of three administrative levels (central government, county councils and municipalities), but only two hierarchical ones. County councils (20 in total, consisting of 18 traditional county councils and two recently formed regions, each consisting of a number of former county councils1) and municipalities (290 in total2) are at the same hierarchical level but are both subordinate to the central government. County councils and municipalities are responsible for the provision of health and social care in Sweden. Each county council covers a geographical area where several municipalities are situated. The number of municipalities in each county council varies between 5 and 49. The number of inhabitants in the county council areas varies between 128,000 and 1,900,000. Traditionally, Swedish county councils have been responsible for health and medical services, while social services have been the responsibility of municipalities at the local level. Home care services have been a part of county councils' health and medical services generally, whereas municipalities have provided home-help service [24].

Generally, the 1990s was a decade of reorganization of the public sector [25–28]. One of the most far-reaching Swedish organizational reforms was the Care of the Elderly Reform (Ädel reform) of 1992, whereby the organization of old-age care was radically changed. One important aim of the reform was to find more efficient ways to organize old-age care under one authority (i.e. to increase the integration of health and social care). The essence of the Ädel reform was that municipalities were given total responsibility for elderly (≥65 years) and old-age care outside of hospitals [29]. As a result of the reform, Swedish old-age care outside of hospitals is currently mainly provided by municipalities and takes place either in special housing for the elderly or in private homes. In special housing for the elderly, health and social care are integrated in one organization.

Most elements of the reform were compulsory, unilaterally decided by central government, and imposed on county councils3 and municipalities. However, the taking over of the responsibility for home care services by municipalities was voluntary. The Swedish government gave county councils and municipalities a free hand to negotiate the organization of home care services [29]. The freedom to negotiate organizational forms locally was intended to result in variation among municipalities, based on local conditions, regarding the responsibility for home care services.

In other words, the reform consisted of a combination of two coordinating mechanisms, namely, central steering from the Swedish government, and incentives to create networks at the regional and local levels [29]. In terms of a common distinction between three ideal typical coordinating mechanisms—hierarchy, market and network [30]—the reform was implemented mainly through the use of hierarchy and, specifically regarding home care services, through the use of networks. The Swedish political system, including its organizations, institutions and culture, can be viewed as a historically evolved configuration, and such national configurations shape the steering processes [31]. Sweden has a large public sector and a strong central state, and political reforms are often carried through by means of using hierarchy. During the last few decades elements of market mechanisms have been introduced in Swedish public sector, and decentralisation from national to sub-national levels has been a common trend [32]. However, deliberate attempts from national government to initiate implementation networks at sub-national levels is a more recent phenomenon in Sweden, and the voluntary elements of the Ädel reform is an early example of this new political “style” [29].

Networks are often viewed in a positive way as a flexible and non-traditional method for solving complex and “cross-cutting issues” [33] or “wicked problems” [34]. Integrated care is often regarded to be such a “cross-cutting issue”, and implementation networks may therefore be expected to be an appropriate form of organization [31]. Though initiated at the national level, the networks of the Swedish home care organization are actually structured through negotiations between county councils and municipalities. Thus, these networks are designed at the regional and local levels.

Two aspects of network structuring are central in this study, namely, the responsibility and provision of home care services. The responsibility rests with either the county council or the municipality. However, responsibility does not necessarily coincide with provision of services. Home care services may be provided by county council, municipality and other actors (e.g. private companies and cooperatives). Different solutions regarding these two aspects result in different local organizational models of home care. Therefore, the terms “network” and “organizational model” will henceforth be used inter changeably.

If the design of networks were determined only by unique local circumstances it would be difficult to find any clear patterns regarding the distribution of local organizational models among Swedish municipalities. However, distribution of organizational forms usually shows clear patterns. Even if the introduction of an organizational model is voluntary its dissemination may still form inter-organizational patterns, due to e.g. imitation and fashion-following. Moreover, the adoption of a new organizational form is not always voluntary. It may also be more or less coercively imposed by strong organizations on weaker ones, or it may be the result of inter-organizational negotiations [35–38]. In all those cases the distribution of organizational models may be expected to form inter-municipal patterns. The shape of those patterns is a matter for empirical investigation.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to study a structural aspect of integrated care, namely, the design and distribution of different organizational solutions regarding the responsibility for and provision of home care for elderly in Swedish municipalities.

Methods

The authors developed a questionnaire containing 28 questions. Most of the questions were of organizational character, including, for example, the provision of home care services. In order to map the organization of home care services, the respondents were asked to specify the providing organizations (county council, municipality, and contractors) and performing occupations (assistant nurse and district nurse). The questionnaire was tested on four municipalities before being sent out, and was found to work well.

The questionnaire and a letter of information about the study were sent to directors of the social welfare services in all Swedish municipalities (n=289). They were informed that participation was voluntary and that answers would be treated confidentially. Moreover, if they wanted to remain anonymous, they were asked not to state their names. Two reminders were sent out. Fifty-six per cent of the respondent municipalities were contacted by phone to clarify their answers, particularly concerning the organization of home care services.

Data were collected during the summer of 2002 and were analyzed with SPSS Version 11.5. One-way ANOVA tests were performed to investigate differences in municipal size and proportion of elderly regarding the responsibility and organization of provision of home care. Moreover, Chi-square tests were performed in order to investigate whether there were any differences, in reluctance to reorganize regarding the home care organization. Level of significance was set to 5%.

Results

A total of 211 answers were received, resulting in a 73% rate of response. The response rate within county councils varied between 50% and 100%. Some of the directors responded themselves, others delegated the task to managers and civil servants at different levels in the municipal old-age care organization. The responding municipalities were evenly distributed, geographically and according to size; the total number of citizens (7,127,035) in the responding municipalities represented 80% of the Swedish population. Number of inhabitants in the responding municipalities varied between 3,294 and 754,948 inhabitants. The proportion of elderly (≥65 years) was 17%.

Besides the municipality–county council boundary, another inter-organizational boundary exists regarding provision of home care services, between public and private providers of home care services. Elements of “privatization” represented only a minor part of home care services in Sweden. All in all, non-public provision of home care services, as a complement to public provision, was represented in 10.5% (22) of the municipalities. Thus, private alternatives in home care are of secondary importance in this study. Therefore, further analysis on private providers is not presented in this article.

We identified three different organizational models of home care. The models represent different degrees of structural integration, and are based on the allocation of responsibility and provision of home care services. The responsibility was either still in the hands of county councils, as it was before the Ädel reform, or transferred to municipalities. In municipalities where the county council was responsible for home care services, the provision could be organized in two ways (model 1 and model 2). On the other hand, where municipalities were responsible for home care services, responsibility and provision coincided in one organizational model (model 3). In the presentation below, the different organizational models appear according to degree of structural integration in the provision of home care.

Organizational model 1 represents the lowest degree of structural integration. County councils were responsible for, and provided home care services. Municipalities provided home-help services. This model was adopted in 23% (48) of the municipalities. Organizational model 2: County councils were responsible for home care services, and qualified health care was provided by county council personnel (district nurses). However, less qualified health care, as well as home help, was provided by assistant nurses employed by municipalities. County councils did not employ assistant nurses and, thus, a separation between responsibility and provision of home care services was built directly into the organizational structure. This model was adopted by 26% (56) of the municipalities. Organizational model 3: Municipalities were responsible for, and provided all home care, including both home help and home care services. This model was the most common one, adopted by 51% (107) of the municipalities.

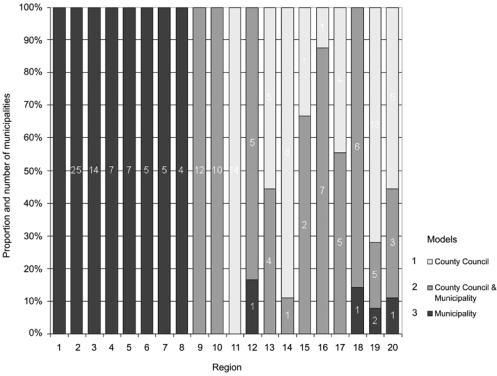

A distinct pattern was identified for the distribution of municipalities with different organizational models of home care. In 55% (11) of the 20 county councils, home care was organized the same way in all municipalities (Figure 1). In 35% (7) of the county councils two models of home care were represented in its municipalities. In 10% (2) of the areas all three ways of organizing home care were identified.

Figure 1.

The organization of provision of home care in county councils.

Thus, in 55% (11) of the county councils one model of providing home care was universally prevailing. In eight of those areas the prevailing model was organizational model 3: municipalities provided all home care. In 75% (15) of the county councils, three-fourths or more of the municipalities had chosen the same model of organization for home care. In 85% (17) of the county councils, two-thirds or more of the municipalities were organized according to the same model of home care. Thus, the organizational structure of the county councils was strongly homogeneous; most county council areas consisted of clusters of municipalities with the same kind of home care organization.

The main aim of this paper is to describe patterns of structural integration of home care, and the causes of these patterns are of secondary interest. However, some potentially influential factors are so conspicuous that they are hard to overlook. Demographical characteristics may be expected to have a general impact on the municipal organization of services. Further, a general preference for reorganizations may be expected to be correlated with the adoption of organizational model 3, the most radical organizational reform. Therefore, in the following, comparisons between the three types of municipalities (i.e. municipalities organized according to model 1, 2 or 3) are made regarding demography and preferences for organizational reforms.

Demography

Municipalities were all demographically equal, regardless of organizational model adopted. Neither number of inhabitants nor proportion of elderly differed between municipalities with different organization of home care.

Reorganization

In total, 73% (154) of Swedish municipalities had completed at least one major reorganization of some kind after the Ädel reform. Of these, 26% (40) also had reorganizations in progress during the summer of 2002. Furthermore, 6% (13) of the municipalities were undergoing reorganizations during the summer of 2002 for the first time since the implementation of the Ädel reform. However, there was also a minority of 21% (43) of the municipalities with no major completed or ongoing reorganization at all since the Ädel reform. The introduction of a new form of structural integration with the Ädel reform, i.e. the transferring of responsibility for home care services (model 3) may be expected to express a general inclination to reorganize municipal activities. However, contrary to expectations, municipalities who had taken over the responsibility for home care services showed no significant differences regarding inclination to reorganize.

However, despite the general inclination to reorganize municipal activities, only 1% (3) of the municipalities stated that their home care organization had gone through any reorganization at all, affecting the relation with county councils, after the Ädel reform. Thus, the organization of home care in Sweden has been stable since the implementation of the Ädel reform.

Discussion

Home care consists of two activities: social services (home help) and medical services (home care services). One form of integrated care is the structural integration of these aspects. In all the organizational models described in the previous section, municipalities were responsible for and provided social services. Thus, the differences between the models concern the organization of home care services.

We identified three different models concerning the responsibility and provision of home care services in private homes in Swedish municipalities. These models represent different degrees of structural integration of home care. Model 1 and 2 were characterized by an organizational separation of responsibility for social and medical aspects of home care: municipalities were responsible for home help services, and county councils for home care services. The differences between the two models do not concern the responsibility but the provision of home care services. In model 1 the provider is the county council, but in model 2 home care services are provided by both county councils and municipalities. Thus, the degree of integration is higher in model 2: cooperation between county councils and municipalities regarding home care services is built into the formal organizational structure. Model 3 represents a still higher degree of structural integration of home care. Municipalities were responsible for and provided both home help and home care services.

The national organization of Swedish home care has a somewhat peculiar design. The distribution of the different organizational models for home care resulted in a sub-national rather than a national structure; county councils tended to form clusters of municipalities with the same kind of organization. In eight of the eleven county council areas where one single model of organization for home care was universally prevailing, municipalities had taken over the responsibility for home care services. This resembles an “all or nothing solution”; either all municipalities in an area took over the responsibility for home care services, or none adopted this solution. There are few exceptions to this rule. This radical organizational change, compared to the situation before the Ädel reform, seems to be strongly connected with unanimity among the municipalities within a county council area.

The distribution pattern of organizational models is also stable over time. Our data show that Swedish municipalities during the 1990s have been inclined to change their organization generally, a result strongly supported by earlier research [25, 27, 28, 39]. However, this is not so regarding the organization of home care. In 1992, more than half of the municipalities in the country took over the responsibility for home care services from the county councils. After that, changes have been few. Only 1% of the municipalities stated that they had changed their home care organization. Thus, after the radical change that occurred with the introduction of the Ädel reform, the organization of home care in Sweden has been remarkably stable.

Possible explanations

No demographical or organizational characteristics associated with different organizational models were found at the municipal level. The organization of home care services is an inter-organizational matter, and the relationship between municipalities and county councils, rather than municipal characteristics, affects the design and distribution of home care organizations.

The design of organization for responsibility and provision of home care is negotiated locally between municipality and county council. Yet, why should this result in a similar organizational structure for all or most municipalities within the same county council area? Three different explanations seem to be at least theoretically conceivable [35–38]. One explanation is processes of imitation between municipalities in the same county council; another is collective negotiations between all concerned municipalities and the county council; a third explanation is asymmetric power relations between the negotiating parties, where one party (the county council) is dominant.

However, in this case processes of imitation are hardly a plausible explanation. Imitation presupposes a process where an “innovation” is first adopted by a forerunner and then imitated by followers [35]. The Ädel reform was introduced at the same time in the whole country and a new organization of home care was adopted overnight in all Swedish municipalities. Thus, there was no time sequence involved where forerunners and followers could adopt the reform at different points in time.

Two of the three above-mentioned explanations are, however, plausible and they are not mutually exclusive. Rather, we consider them complementary. Collective negotiations are facilitated by the fact that municipalities are organized according to county council area affiliation. Regarding the power relations between county councils and municipalities the situation is more uncertain: the negotiations regarding the organization of home care services took place at the political level and we have not found any research at all neither regarding these negotiations nor regarding the power relations more generally. (The absence of research in this area is in itself remarkable.) However, regarding the operative level, medical services have for several reasons (financial resources, professional status) a stronger position than social services, in Sweden as well as elsewhere [21, 40, 41]. Whether this asymmetry at the operative level is also reflected at the political level is not clear, but our data are certainly not inconsistent with the assumption that county councils are more powerful than municipalities. Thus, the distribution of the different organizational models of home care may be explained by collective negotiations and/or asymmetric power relations, but not imitation.

A possible explanation for the absence of further organizational reforms in the area of home care could be a lack of perceived problems with the present organization. This explanation gains partly support from evaluations. The Ädel reform has been regarded as partly successful by evaluators [42]. However, some old problems remain and others have been created or aggravated by the reform, particularly in municipalities of types 1 and 2, e.g. increased costs, fragmentation, lack of co-ordination, and no possibilities to influence the home care activity area as a whole [42–44].

Thus, in spite of a general inclination to reorganize among Swedish municipalities, and despite existing problems in the home care organization [43] few efforts have been made to solve the problems through organizational reforms. How could that be?

The same factors that explain the distribution of organizational home care models (collective negotiations and/or asymmetric power relations) may also explain the reluctance to reorganize the home care organization. Each municipality faces a combination of a necessity to negotiate with the county council, and a strong conformity among municipalities within the same county council area. Thus, if one municipality wishes to change its home care organization, it has to pass a high threshold, namely, not only negotiate with a powerful county council but also sometimes negotiate with other municipalities to make them adopt the same organizational reform. This inter-organizational structure seems to create considerable inertia at the network level.

Limitations of the study

Even though the Ädel reform has been extensively evaluated [42], international publications about the organization of home care in Sweden are rare. Further research from an organizational perspective is needed, preferably by way of comparisons between the three types of municipalities, regarding, e.g. quality of care and inter-professional cooperation across organizational boundaries.

Despite having distributed the questionnaire at the beginning of the summer vacation the rate of response was high (73%). It would probably have been even higher if another time had been chosen.

In spite of the high rate of response, the fact remains that 27% of the municipalities did not answer the questionnaire. However, the missing cases were evenly distributed all over the country in municipalities of different sizes. The internal loss is partly due to our way of presenting combinations of data, and partly to unanswered questions in some questionnaires.

To test its validity, the questionnaire was sent to four municipalities. The respondents, who were asked to give constructive criticism, had no objections to the design and content of the questionnaire. Therefore, we consider the validity of the study to be acceptable. The reliability of the study was confirmed through follow-up telephone calls with 118 municipalities.

Conclusions

The organizational structure of home care in Sweden was radically changed through the Ädel reform of 1992, and three different organizational models arose. However, the models have not been disseminated in a national organizational field, but rather in sub-national networks at the county council level within the field. The organizational structure within the county council areas was highly homogeneous. The highest degree of structural integration of home care, i.e. municipal responsibility for and provision of home care services as well as social services, presupposed the most radical organizational change, and was related to unanimity among the municipalities within each county council area; in 8 of 11 entirely homogeneous county council areas the municipalities had all chosen the most radical change (i.e. organizational model 3), and few municipalities outside these areas had chosen this solution.

However, once the Ädel reform was implemented the organizational structure of home care has remained unchanged. The inter-organizational network structure within the county councils was designed in a way that made it difficult for individual municipalities to change their organization of home care. The necessity to reach an agreement with the county council as well as with other municipalities within the region seems to have created an almost insurmountable threshold.

Our conclusion is a paradox: The decentralist intention of the Ädel reform—to give actors at the municipal and county council levels freedom to integrate home care according to varying local circumstances—has resulted in an inter-organizational network structure leading to conformity within county council areas, and local home care organizations which are highly inert and difficult to change.

It seems entirely possible for national governments to bring about structural integration of home care through major organizational reforms, at least in countries with strong political institutions [31]. However, the use of hierarchical power in order to decentralize, by creating network structures at different sub-national levels results in inter-organizational structures, which, once established, are highly difficult to change. Thus, after one change, the inter-organizational structure is frozen.

Therefore, if structural integration is the political goal, decentralisation to county council and municipal levels may not be the most appropriate means, because those municipalities who initially choose not to adopt an organizational solution leading to full structural integration cannot change their minds later. They are locked into a frozen structure, and it probably takes another government decision to unfreeze it.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anders Röjde, Department of Social Work and Annika Tillander, Department of Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, who gave valuable advice and support in statistical matters. We are also grateful to Klas Borell, Department of Social Work, Mid Sweden University, for valuable comments on the manuscript. The study was funded by grants from Mid Sweden University, Department of Health Sciences and Uppsala University, Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences and the Research and Development Unit for Elderly Care in North-West Stockholm County Council, Sweden. The study was also funded by grants from County of Jämtland Fund for Cancer Research and The Swedish Society of Nursing.

Footnotes

Henceforth, county councils and regions will both be called county councils.

289 municipalities at the time of data collection.

1992, the number of county councils were 25 (i.e. the two regions were not yet formed).

Contributor Information

Nils Olof Hedman, Department of Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden and Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Roine Johansson, Department of Social Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Östersund, Sweden.

Urban Rosenqvist, Department of Public Health and Caring Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Reviewers

Anna-Karin Edberg, PhD, Associate Professor Department of Health Sciences Lund University, Sweden.

Nick Gould, Senior Lecturer, Networks and Integrated Care, Welsh Institute for Health and Social Care, University of Glamorgan, United Kingdom.

Gunnar Ljunggren, MD, PhD, Forum/Centre for Care Development, Stockholm County Council, Stockholm, Sweden.

Kirstein Rummery, Professor of Social Policy, LLB(Hons), MA, PhD, Department of Applied Social Sciences, University of Stirling, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Forti EM, Johnson JA, Graber DR. Aging in America: challenges and strategies for health care delivery. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration. 2000 Fall;23(2):203–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobzone S. Coping with aging: international challenges. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2000 May-Jun;19(3):213–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knickman JR, Snell EK. The 2030 problem: caring for aging baby boomers. Health Services Research. 2002 Aug;37(4):849–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batljan I, Lagergren M. Inpatient/outpatient health care costs and remaining years of life—effect of decreasing mortality on future acute health care demand. Social Science and Medicine. 2004 Dec;59(12):2459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon M. Problems of an aging population in an era of technology. Journal of Canadian Dental Association. 2000 Jun;66(6):320–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen M, Haglund B. From healthy survivors to sick survivors—implications for the twenty-first century. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2005;33(2):151–5. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoeckle JD. The Citadel cannot hold: technologies go outside the hospital, patients and doctors too. The Milbank Quarterly. 1995;73(1):3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoeckle JD, Lorch S. Why go see the doctor? Care goes from office to home as technology divorces function from geography. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1997 Fall;13(4):537–46. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300010011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson A, Beck-Friis B, Britton M, Carlsson P, Fridegren I. Avancerad hemsjukvård och hemrehabilitering. Effekter och kostnader. [Advanced home health care and home rehabilitation—reviewing the scientific evidence on costs and effects]. Stockholm: The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care; 1999. Available from: http://www.sbu.se/www/index.asp [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Healy J, McKee M. The evolution of hospital systems. In: McKee M, Healy J, editors. Hospitals in a changing Europe. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2003. pp. 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutten JBF, Kerkstra A, editors. Home care in Europe. A country-specific guide to its organization and financing. Aldershot: Arena; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daatland SO. Ageing, families and welfare systems: comparative perspectives. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie. 2001 Feb;34(1):16–20. doi: 10.1007/s003910170086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leichsenring K. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons—A European overview. In: Leichsenring K, Alaszewski AM, editors. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons—A European overview of issues at stake. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2004. pp. 9–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman A, Rummery K. Social services representation in Primary Care Groups and Trusts. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2003 Aug;17(3):273–80. doi: 10.1080/1356182031000122898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey B, Levin E, Iliffe S, Kharicha K. Integrating health and social care: implications for joint working and community care outcomes for older people. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2005 Jan;19(1):22–34. doi: 10.1080/1356182040021734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leichsenring K, Alaszewski AM, editors. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons—a European overview of issues at stake. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rummery K. Changes in primary health care policy: the implications for joint commissioning with social services. Health and Social Care in the Community. 1998 Nov;6(6):429–37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1998.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rummery K, Coleman A. Primary health and social care services in the UK: progress towards partnership? Social Science and Medicine. 2003 Apr;56(8):1773–82. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Raak A, Mur-Veeman I, Hardy B, Steenbergen M, Paulus A, editors. Integrated care in Europe. Description and comparison of integrated care in six EU countries. Maarssen: Elsevier gezondheidszorg; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy B, van Raak A, Mur-Veeman I, Steenbergen M, Paulus A. Introduction. In: van Raak A, Mur-Veeman I, Hardy B, Steenbergen M, Paulus A, editors. Integrated care in Europe. Description and comparison of integrated care in six EU countries. Maarssen: Elsevier gezondheidszorg; 2003. pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alaszewski A, Billings J, Coxon K. Integrated health and social care for older persons: theoretical and conceptual issues. In: Leichsenring K, Alaszewski AM, editors. Providing integrated health and social care for older persons—A European overview of issues at stake. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2004. pp. 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson G, Karlberg I. Integrated care for the elderly. The background and effects of the reform of Swedish care of the elderly. International Journal of Integrated Care [serial online] 2000 Nov 1;1 Available from: http://www.ijic.org/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerkstra A, Hutten JBF. A Cross-national comparison on home care in Europe: summary of the findings. In: Hutten JBF, Kerkstra A, editors. Home care in Europe. A country-specific guide to its organization and financing. Aldershot: Arena; 1996. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafsson RÅ, Traditionernas ok. Den svenska hälso- och sjukvårdens organisering i historie-sociologiskt perspektiv. [Tradition, control and activity demarcation—The Swedish health care system in a historical sociological perspective. [PhD thesis]]. Solna: Esselte studium; 1987. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobsson B. Local governments and institutional change—Swedish experiences. Stockholm: Stockholm Centre for Organizational Research; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Czarniawska B, Sevón G, editors. Translating organizational change. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunsson N, Sahlin-Andersson K. Constructing organizations: the example of public sector reform. Organization Studies. 2000;21(4):721–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunsson N, Olsen P. The reforming organization. London: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson R, Borell K. Central steering and local networks: old-age care in Sweden. Public Administration. 1999 Fall;77(3):585–98. Available from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9299.00169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson G, Frances J, Levacic R, Mitchell J. Markets, hierarchies and networks. The coordination of social life. London: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kümpers S, van Raak A, Hardy B, Mur I. The influence of institutions and culture on health policies: different approaches to integrated care in England and The Netherlands. Public Administration. 2002 Summer;80(2):339–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordlund A. Department of Sociology [PhD thesis] Umeå: Umeå University; 2002. Resilient Welfare States—Nordic welfare state development in the late 20th Century. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin S. Implementing “Best Value”: local public services in transition. Public Administration. 2000 Spring;78(1):209–27. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Toole LJ. Treating networks seriously: practical and research-based agendas in public administration. Public Administration. 1997 Spring;75(1):45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Røvik KA. Deinstitutionalization and the logic of fashion. In: Czarniawska B, Sevón G, editors. Translating organizational change. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 139–72. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Powell WW, DiMaggio DJ, editors. The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37.DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW. The Iron Cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review. 1983;48(2):147–60. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrahamson E. Technical and aesthetic fashion. In: Czarniawska B, Sevón G, editors. Translating organizational change. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 117–37. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forssell A, Jansson D. In: Translating organizational change. Czarniawska-Joerges B, Sevón G, editors. Berlin: de Gruyter; 1996. pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freidson E. The profession of medicine. New York: Dodd, Mead and Co; 1970. The Logic of organizational transformation: on the conversion of Non-Business Organizations. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berg E. Department of Human Work Sciences/Social Psychology of Working Life. Luleå: Luleå University of Technology; 1994. Det ojämlika mötet: en studie av samverkan i hemvården mellan kommunens hemtjänst och landstingets primärvård. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Socialstyrelsen [The National Board of Health and Welfare] Ädelreformen. slutrapport. [The “Ädel Reform” final report 1996]. Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 1996. [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sammanhållen hemvård—Betänkande från Äldrevådsutredningen [Integrated home care] Stockholm: Socialdepartementet; 2004. (SOU—Official Government Reports Series: 2004:68). Available from: http://www.regeringen.se/sb/d/189/a/26584 [in Swedish] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henriksen E, Selander G, Rosenqvist U. Can we bridge the gap between goals and practice through a common vision? A study of politicians and managers' understanding of the provisions of elderly care services. Health Policy. 2003 Aug;65(2):129–37. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(02)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]