Abstract

Aim

The efficacy and safety of repeated injections of intravitreal triamcinolone (IVTA) for diabetic macular oedema is unclear, with results of previous reports conflicting.

Methods

This is a prospective, observational case series of 27 eyes receiving IVTA for diabetic macular oedema. LogMAR visual acuity (VA) and central macular thickness (CMT) were measured at baseline and in 3 to 6 monthly intervals for up to 24 months, then correlated with the number of IVTA injections given.

Results

One IVTA injection was required in 6 (18%) eyes, 2 in 8 (24%) eyes, 3 in 13 (39%) eyes and 4–5 in 6 (18%) eyes. VA improved in all patients, but neither the final improvement in VA nor the absolute improvement in CMT from baseline to 24 months correlated with the number of injections received (p = 0.44 and 0.84, respectively). Cataract surgery was more frequent in eyes receiving more injections (p = 0.01).

Conclusions

This study suggests that repeated injections of IVTA continue to be as effective as the first over a 2‐year period. The probability of cataract surgery increases with an increasing number of injections.

Whether repeated injections of high‐dose, locally delivered corticosteroids continue to be as safe and efficacious as the first injection is a vital issue that will influence how these treatments will be used for conditions such as severe diabetic macular oedema (DMO). The matter remains unresolved, with previous studies reporting conflicting results.1,2

We have recently reported the results of a double‐masked, placebo‐controlled randomised clinical trial which demonstrated that intravitreal triamcinolone (IVTA) can improve visual acuity and reduce the risk of visual loss in eyes with DMO that have failed standard laser treatment over a 2‐year period.3,4 However, more than one injection was required in 27/33 (82%) treated eyes. We now report the efficacy, as reflected by change in visual acuity and central macular thickness, and safety (requirement for treatment of cataract or glaucoma) of multiple injections of IVTA in actively treated eyes from this study in order to determine whether repeated injections are associated with reduced efficacy and greater risk.

Methods

Patient enrolment

Patients were recruited from the Retina Clinics of the Sydney Eye Hospital from March 2002 to April 2003. Patients with severe (involving the central fovea5) DMO, diffuse or focal, 3 or more months after at least one session of laser treatment and best corrected visual acuity in the affected eye(s) of 20/30 or worse were included. Exclusion criteria included uncontrolled glaucoma. Eyes were randomly allocated to receive either IVTA or a placebo subconjunctival injection of saline. Only eyes that were randomised to receive treatment with IVTA were included in the present analysis. The trial was approved by the University of Sydney research ethics committee. Safety data were reviewed by an independent safety monitoring committee.

Data collection and masking

The measurement of best corrected LogMAR visual acuity was performed with ETDRS charts using standardised procedures by certified, masked examiners. Intraocular pressures were measured using Goldman applanation tonometry. When it became available, optical coherence tomography (OCT) was used to measure central macular thickness (1 mm diameter). A masked clinical observer graded cataracts using the Age Related Eye Diseases Study (AREDS) photographic standard.6

Visual acuity, OCT and intraocular pressure data were obtained from baseline to 24 months with different time intervals, but at least 3‐monthly, and have been reported here in 6‐month intervals. Data missing at any 6‐month interval (ie, 6, 12, 18 or 24 months) were replaced by the previous values closest to that time point. Data have been considered up to the nearest 6‐month interval for the patients who had surgery and censored after the surgery. For example, if a patient had a surgery at 16 months, his/her biometric data were considered up to 18 months (the nearest 6‐month interval). Based on this criterion, one patient with cataract surgery had biometric data up to 12 months, 3 had data up to 18 months and the other 15 had data up to 24 months.

Requirement for glaucoma therapy or cataract surgery was used as the simplest and most clinically relevant safety outcomes. All eyes recording intraocular pressure of greater than 24 mm Hg at any visit were placed on glaucoma therapy. Prostaglandin agonists were avoided because of a suspicion that they may aggravate macular oedema. β blockers were used in the first instance, with α adrenergic drugs used as second‐line medication. The decision to institute glaucoma therapy at lower levels of intraocular pressure was made along conventional lines in discussion with the patient, based on the degree and duration of the intraocular pressure elevation and extent of glaucomatous optic neuropathy if present. Eyes that did not respond satisfactorily to first‐line medication were referred to the glaucoma service for further evaluation and treatment as appropriate. The decision to perform cataract surgery was also made in discussion with the patient after they had developed at least a 2+ posterior subcapsular cataract, taking into account the level of visual acuity in both the affected and fellow eyes. All eyes that underwent cataract surgery received a repeat injection of triamcinolone at the time of surgery.

Treatment

Intravitreal IVTA (0.1 ml Kenacort 40 [40 mg/ml triamcinolone acetonide, Bristol‐Myers Squibb Pharmaceuticals, Australia]) was injected into the vitreous.3 Retreatment was considered at each visit as long as treatments were at least 6 months apart. Eyes with a reduction of visual acuity of at least five letters from previous peak value and persistent central macular thickness greater than 250 micron received retreatment with study medication. If visual acuity had not improved by five or more letters when measured 4 weeks later and macular thickening persisted, then fluorescein angiography was performed and further laser treatment was applied if the investigator thought it would be beneficial.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of the effect of multiple injections described herein was not a prospectively defined outcome. There was a potential maximum of five injections per participant over the study period of 24 months. For analysis, the number of injections was categorised into four groups (single injection, 2, 3, and 4 or 5). We initially used generalised linear models to estimate mean visual acuity or central macular thickness comparing injection categories over the 24‐month visit by 6‐monthly intervals, adjusting for age and gender. The paired sample t test was used to compare mean changes in visual acuity and macular thickness between the baseline and final 24‐month visit for injection categories. Test of trend in visual acuity or macular thickness from baseline over the 24 months at 6‐monthly intervals comparing injection categories was determined by using generalised estimating equation models by Liang and Zeger.7 The associations between injection categories and cataract and glaucoma surgery status were determined by the χ2 test statistic.

We also compared the mean visual acuity and macular thickness immediately prior to the injection with the best post‐injection values within 6 months after each injection. For this analysis, all data were grouped according to the injection categories, irrespective of how many injections each eye received during the study, and the means were compared for injection categories by using the paired sample t test. All analyses were performed in SPSS version 12.0.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) and Stata version 9 and the results were reported significant for p⩽0.05.

Results

Thirty‐four eyes were randomised to receive IVTA, of which two‐year data were available for 31 (91%). One patient died soon after entry and was not included in this analysis, leaving 33 for the current analysis. A total of 87 injections of IVTA for these 33 eyes were given over the 2 years of the study. Only one injection was required in 6 (18%) eyes, 2 in 8 (24%) eyes, 3 in 13 (39%) eyes and 4–5 in 6 (18%) eyes. There was no significant difference with respect to gender, age or baseline intraocular pressure and central macular thickness across these injection categories (table 1). The mean baseline visual acuity of eyes that eventually had more injections was less than that of the eyes that had fewer but the trend according to number of injections received during the study was not statistically significant. There was a significant trend towards longer duration of diabetes and number of injections received.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of 33 patients participating in the study.

| Characteristic | Number of injections | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N = 33 | 1, N = 6 | 2, N = 8 | 3, N = 13 | 4–5, N = 6 | p | ||||||

| Gender | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Male | 18 | 54.5 | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 50.0 | 8 | 61.5 | 4 | 66.7 | 0.62 |

| Female | 15 | 45.5 | 4 | 66.7 | 4 | 50.0 | 5 | 38.5 | 2 | 33.3 | |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age, years | 63.3 | 10.1 | 59.2 | 6.4 | 63.3 | 11.0 | 62.2 | 8.4 | 69.6 | 14.2 | 0.34 |

| VA baseline | 60.4 | 12.0 | 68.8 | 6.4 | 61.6 | 14.8 | 55.7 | 12.8 | 60.3 | 6.8 | 0.17 |

| MT baseline | 441 | 122 | 405 | 99 | 407 | 74 | 503 | 125 | 381 | 161 | 0.27 |

| IOP baseline | 16.6 | 2.6 | 17.3 | 1.4 | 17.3 | 3.2 | 16.7 | 2.3 | 14.5 | 2.7 | 0.17 |

| HbA1C | 8.0 | 1.36 | 6.9 | 0.83 | 7.6 | 1.09 | 8.3 | 1.37 | 9.0 | 1.61 | 0.06 |

| Duration of diabetes | 15.4 | 8.8 | 12.4 | 6.1 | 11.1 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 6.8 | 24.8 | 12.6 | 0.02 |

IOP, intraocular pressure; MT, macular thickness; N, number at risk; n, number with categorical endpoint; VA, visual acuity. Data are proportions or means with standard deviation (SD).

The response in visual acuity and central macular thickness at 6‐month visits by injection categories adjusted for duration of disease and baseline glycosylated haemoglobin is presented in table 2. This table shows the overall course of the injection groups during the study, and does not necessarily reflect the full response to the IVTA injections, since data are included for eyes that may have developed recurrent oedema and a decline in vision at any of the visits that would have been eligible for re‐injection. There was a trend towards worse vision in the eyes that received multiple injections, which was statistically significant after 12 and 18 months. However, the mean improvement in visual acuity after 24 months bore no correlation with the number of injections received. Visual acuity improved in all groups at different times and there was no significant trend towards progressive improvement of vision over the course of the study. There was no correlation between the number of injections received and absolute level of central macular thickness or change from one visit to the next. There was, however, a significant trend towards progressive improvement in central macular thickness over the course of the study for those receiving 1 and 3 injections, but this was not significant for those receiving 2 and 4–5 injections.

Table 2 Effect of multiple IVTA injections on visual acuity and central macular thickness over the course of the study.

| 1 injection, N = 6 | 2 injections, N = 8 | 3 injections, N = 13 | 4–5 injections, N = 6 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Δ | Mean (SD) | Δ | Mean (SD) | Δ | Mean (SD) | Δ | p* | |

| Visual acuity | |||||||||

| Baseline | 68.8 (6.4) | 61.6 (14.8) | 55.7 (12.8) | 60.3 (6.8) | 0.11 | ||||

| 6.9 | 5.4 | 8.7 | −3.0 | 0.05 | |||||

| 6 months | 75.7 (6.5) | 67.0 (18.9) | 64.4 (11.3) | 57.3 (5.3) | 0.31 | ||||

| −0.5 | −0.5 | −9.3 | −3.1 | 0.25 | |||||

| 12 months | 75.2 (7.4) | 66.5 (14.7) | 55.1 (14.8) | 54.2 (9.4) | 0.10 | ||||

| −1.2 | 0.5 | 2.5 | 6.0 | 0.65 | |||||

| 18 months | 74.0 (6.4) | 67.0 (16.2) | 57.6 (10.3) | 60.2 (11.8) | 0.02 | ||||

| 2.0 | −7.0 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 0.15 | |||||

| 24 months | 76.0 (8.6) | 60.0 (19.1) | 58.9 (11.7) | 65.7 (17.9) | 0.12 | ||||

| p (trend)† | 0.54 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.38 | |||||

| Final change | 7.2 | 0.14 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 0.44 | ||||

| p‡ | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.006 | 0.47 | |||||

| Macular thickness | |||||||||

| Baseline | 405 (99) | 407 (74) | 503 (125) | 381 (161) | 0.36 | ||||

| 168 | 126 | 157 | 2 | 0.82 | |||||

| 6 months | 237 (51) | 281 (62) | 346 (152) | 379 (149) | 0.23 | ||||

| −35 | −40 | −6 | 43 | 0.99 | |||||

| 12 months | 272 (135) | 321 (104) | 352 (71) | 336 (147) | 0.23 | ||||

| 36 | 30 | −8 | 63 | 0.70 | |||||

| 18 months | 236 (53) | 291 (103) | 360 (140) | 293 (105) | 0.31 | ||||

| −3 | 9 | 72 | 48 | 0.70 | |||||

| 24 months | 239 (57) | 282 (126) | 288 (98) | 245 (43) | 0.62 | ||||

| p (trend)† | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.12 | |||||

| Final change | 148 | 92 | 172 | 88 | 0.84 | ||||

| p‡ | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.37 | |||||

Data are grouped according to number of injections received during the study; Δ, change between consecutive 6‐month visits. *p value compares injection categories adjusting for duration of diabetes and HbA1C; †p value compares trend in visual acuity over 24 months; ‡p value compares baseline and 24‐month visit.

Safety outcomes by number of injections received and adjusted for diabetes duration and baseline glycosylated haemoglobin level are presented in table 3. There was a highly significant correlation between the number of injections received and the need for cataract surgery. The probability of requiring glaucoma medication did not correlate with increasing numbers of injections (p = 0.43).

Table 3 Rate of cataract surgery and glaucoma therapy by injection categories.

| 1 injection, N = 6 | 2 injections, N = 8 | 3 injections, N = 13 | 4–5 injections, N = 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | p* | |

| Cataract surgery | |||||

| No | 6 (100.0) | 6 (75.0) | 4 (30.8) | 2 (33.3) | 0.01 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (25.0) | 9 (69.2) | 4 (66.7) | |

| Glaucoma therapy | |||||

| No | 6 (100.0) | 5 (62.5) | 8 (61.5) | 3 (50.0) | 0.43 |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 3 (50.0) |

N, number at risk; n, number with categorical endpoint. Data are grouped according to how many injections each eye received during the study. *p value compares injection categories adjusting for duration of diabetes and HbA1C.

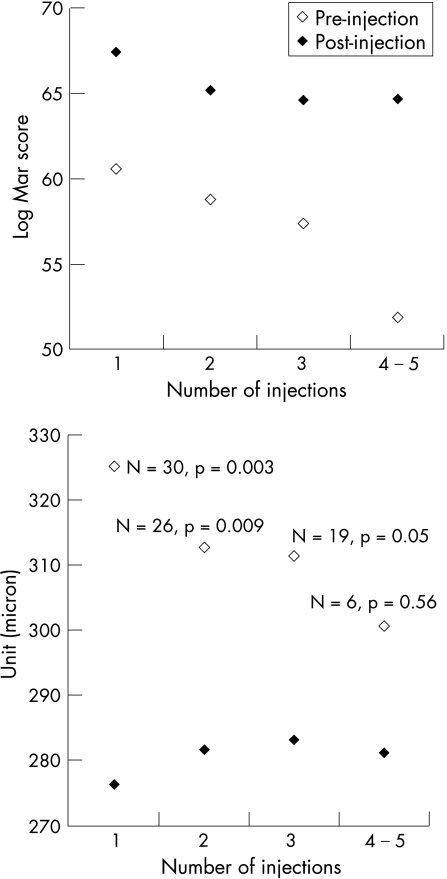

The mean efficacy response of all eyes after the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th–5th injections, irrespective of how many injections each eye actually received during the study, is presented in fig 1. In contrast to the data presented in table 2, in this analysis the pre‐injection values are compared with the best post‐injection value whenever it occurred in the 6 months after the injection, thus eyes that were eligible for retreatment with IVTA are excluded. Mean visual acuity improved significantly after each injection with no correlation between number of injections and degree of improvement. The numbers included in the macular thickness analysis are less than those included in the VA analysis because OCT data became available only after the study commenced. Central macular thickness improved less with increasing numbers of injections, but this may be because the pre‐injection thickness was progressively lower, since the mean central macular thickness improved to a similar level after each successive injection.

Figure 1 Mean visual acuity (top) and macular thickness (bottom) immediately prior to IVTA injection compared with the best post‐injection values within 6 months after each injection. Data are grouped according to number of injection, irrespective of how many injections each eye received during the study.

Discussion

The data we present in this study do not support the hypothesis that repeated injections of IVTA are less efficacious than the first. When examined according to the total number of injections received during the study, there was a trend towards worse vision in the eyes that received more injections, but this was evident at the baseline visit before treatments had started and was most likely because the eyes that required more treatments had more advanced DMO to begin with. Importantly, there was no trend at all between number of injections and absolute improvement in vision from the baseline to the 24‐month visit (eg, 7.2 letters for one injection versus 6.3 letters for 4–5 injections, p = 0.44). Moreover, by this analysis there was no correlation at all between absolute levels of, or improvement in, central macular thickness according to number of injections at any time during the study. When pre‐injection levels of visual acuity and central macular thickness were compared with the best post‐injection level and eyes were grouped according to injection number, irrespective of how many injections they actually received during the study, it was evident that visual acuity improved significantly and to a similar extent after each successive injection (see fig 1). Cataract surgery may have contributed to the largest improvement occurring in the group receiving 4–5 injections; however, this would not account for the improvement in central macular thickness that was also seen after each successive injection in this group.

The data do, however, support the hypothesis that repeated injections are associated with an increased probability of steroid‐related adverse events. These risks are more evident in the present study than in previous reports, because we followed patients closely for 2 years. There was a highly significant association between multiple injections and probability of cataract surgery, with no eyes receiving only 1 injection undergoing surgery compared with 13 or 19 (68%) eyes receiving 3 or more injections. However, there was no correlation between requirement for glaucoma therapy and number of injections. In a randomised clinical trial of a single injection of IVTA for exudative age‐related macular degeneration, glaucoma therapy and cataract surgery were required in 41% and 34%, respectively, of 75 treated eyes.8

The significant correlation between duration of disease and number of injections required suggests, unsurprisingly, that patients with more advanced disease are likely to require more treatments. However, adjustment of results concerning changes in visual acuity and central macular thickness for duration of diabetes and baseline glycosylated haemoglobin did not alter the significance of any of the comparisons at the level of p = 0.05 (unadjusted p values not shown), suggesting that patients with more advanced disease may respond as well to IVTA as those with milder retinopathy.

Comparison of our results with other studies provides additional insights. Jonas et al found no difference in the visual acuity and intraocular pressure response of a second (n = 22) and third (n = 4) injection of around 20 mg IVTA.1 Our study differed from theirs in that we used masked examiners to measure best corrected LogMAR visual acuity in a prospectively defined group of patients, we included OCT measurement of central macular thickness, our numbers were somewhat larger and follow‐up was significantly longer, allowing us to also study the effect of multiple injections on the probability of developing cataracts.

In contrast to the findings of Jonas et al, Chan et al found, in a retrospective case series of 10 patients, that both visual acuity and central foveal thickness improved less after a second IVTA injection.2 In fact macular oedema improved much more significantly in that study than did the visual acuity. We have previously described the poor correlation between improvement in macular thickness and visual acuity after IVTA injections for diabetic macular oedema.9 Part of the discrepancy between our study and that of Chan et al may lie in the smaller numbers in their study. Chan et al. appear to have studied patients with less advanced disease, since only 10% of eyes in their initial trial underwent re‐injection, whereas in our study it was 82%.

Limitations of this study include small patient numbers in each injection category, which do not allow more meaningful evaluation of trends, and only medium‐term patient follow‐up. Examining the data according to the injection number irrespective of how many injections were eventually given to each eye boosted the power of the analysis, but even so the numbers receiving only 1 as well as 4–5 injections were small. A larger study might discern changes in efficacy and safety with multiple injections that were not evident in the present sample. While it is reassuring that multiple injections appear to remain efficacious over 2 years, it is still possible that efficacy will be lost over a longer period for which many people with severe DMO will still require therapy.

The data from the present study give practitioners confidence that the efficacy of multiple injections appears to hold up for up to 2 years. Our study confirms the view that multiple injections are, however, associated with an increased probability of steroid‐induced adverse events, particularly cataracts. Physicians and patients should consider this information when considering using multiple injections of IVTA for recalcitrant DMO, particularly since the response of these eyes to cataract surgery has not been well studied.

Acknowledgements

The safety monitoring committee comprised: Jeremy Smith, FRANZCO (Chair), Paul Power and Jie Jin Wang.

Abbreviations

CMT - central macular thickness

DMO - diabetic macular oedema

IVTA - intravitreal triamcinolone

OCT - optical coherence tomography

VA - visual acuity

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Sydney Eye Hospital Foundation, the Ophthalmic Research Institute of Australia, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and the Diabetes Australia Research Trust. The study was investigator‐initiated and unsupported by the pharmaceutical industry.

Competing interests: MG is included as an inventor on patents relating to the formulation of triamcinolone for ocular use and its use for the treatment of retinal neovascularisation but not macular oedema. He has received research funding, as well as honoraria and travel expenses for participation on advisory boards, from Allergan, which is developing steroids for the treatment of macular disease. The other authors have no conflicting or proprietary interests.

References

- 1.Jonas J B, Spandau U H, Kamppeter B A.et al Repeated intravitreal high‐dosage injections of triamcinolone acetonide for diffuse diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2006113800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan C K, Mohamed S, Shanmugam M P.et al Decreasing efficacy of repeated intravitreal triamcinolone injections in diabetic macular oedema. Br J Ophthalmol 2006901137–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutter F K P, Simpson J M, Gillies M C. Intravitreal triamcinolone for diabetic macular edema that persists after laser treatment: 3 months efficacy and safety results of a prospective, randomized, double‐masked, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology 20041112044–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies M C, Sutter F K P, Simpson J M.et al Intravitreal triamcinolone for refractory diabetic macular oedema: 2‐year results of a double‐masked, placebo‐controlled, randomised clinical trial. Ophthalmology 20061131533–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkinson C P, Ferris F L, 3rd, Klein R E.et al Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 20031101677–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The age‐related eye disease study (AREDS) system for classifying cataracts from photographs: AREDS report no 4. Am J Ophthalmol 2001131167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang K Y, Zeger S L. Longitudinal data analysis using general linear models. Biometrika 19867313–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillies M C, Luo W, Hunyor A B.et al Safety of an intravitreal injection of triamcinolone acetonide: results from a randomised clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2004122336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson J, Zhu M, Sutter F.et al Relation between reduction of foveal thickness and visual acuity in diabetic macular edema treated with intravitreal triamcinolone. Am J Ophthalmol 2005139802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]