Abstract

Fusarium is a filamentous fungus widely distributed in plants and in the soil. Most species are more common at tropical and subtropical areas. Besides being a common contaminant and a well‐known plant pathogen, Fusarium sp may cause various infections in humans. However, it has not yet been reported as being the pathogen of urinary tract infection. A 67‐year‐old woman had extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for renal stones 7 and 6 years ago, respectively. She had had fever, chillness, urinary urgency and frequency for 6 days. Routine testing of urine showed numerous leucocytes. She was admitted under the impression of urinary tract infection. On admission, many spindle‐shaped structures were found in the urine smears. This shows that Fusarium was identified. Fusarium may be the pathogen of the urinary tract infection, particularly when urolithiasis is present.

Over the past decade, there has been a marked increase in opportunist infection by fungal pathogens involving the urinary tract. This increasing incidence in fungal urinary tract infection is associated with extensive and prolonged use of broad‐spectrum antimicrobial agents, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive and cytotoxic drugs.1 Other important risk factors include higher age, diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, haemodialysis, renal transplantation, malignancy, nephrolithiasis, and structural or functional abnormalities of the urinary tract, with indwelling urinary catheter or nephrostomy.1,2,3 Fungal urinary tract infections are most commonly caused by Candida species.2,3,4 Fungal infections of the urinary tract may also be caused by Cryptococcus,3Coccidioides,5Aspergillus,6Histoplasma7 and Curvularia species.8 However, Fusarium species have not been previously reported as pathogenic fungi in the urinary tract in the English literature.

Case report

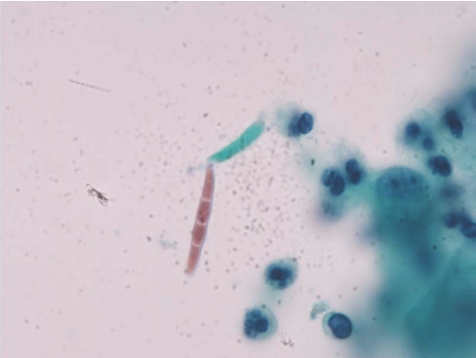

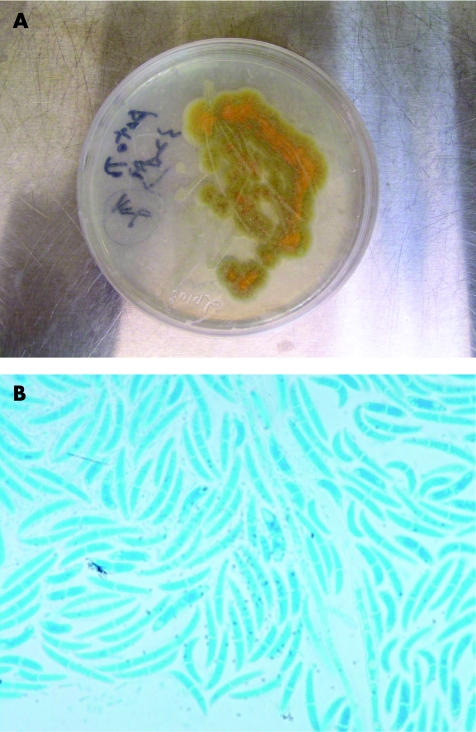

A 67‐year‐old woman had received extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for renal stones 7 and 6 years ago, respectively. She had had fever, chills, urinary urgency and frequency, poor appetite and general weakness for 6 days. Urine routine analysis showed numerous leucocytes. Considering the possibility of urinary tract infection, she was admitted to the hospital. On admission, cytological examination of urine specimen showed many sickled to fusiform macroconidia (3−8×11−70 μm) with 3–5 septa (fig 1). Fusariosis of the urinary tract was suspected. The urine specimen was then cultured with Sabouraud dextrose agar at 30°C for 7 days. The colony surface at first looked like white wool, later turning cream‐coloured and leather‐like in appearance. The back view of the colony had a leather‐like centre and a tan margin (fig 2A). Hyaline septate hyphae, conidiophores, phialides, macroconidia and microconidia were found microscopically (fig 2B). Fusariosis of the urinary tract due to Fusarium species was confirmed. The patient was treated with percutaneous nephrostomy, double J and hydration. She was discharged with improved condition.

Figure 1 Cytological examinaion of urine with Papanicolaou staining showed many sickled to fusiform macroconidia (3−8×11−70 μm) with 3–5 septa (Papanicolaou stain, original magnification, ×1000).

Figure 2 (A) After being cultured with Sabouraud dextrose agar at 30°C for 7 days, the back view of the colony had a leather‐like centre and a tan margin. (B) In this field, the hyaline septate hyphae, a phialide, abundant, large, sickle‐(canoe)‐shaped macroconidia with 1–4 septa, and some small, oval to cylindric, one‐celled or two‐celled microconidia were found microscopically (lactophenol cotton blue stain, original magnification, ×1000).

Discussion

Fusarium is a filamentous fungus widely distributed in plants and in the soil. Most species are common in tropical and subtropical areas.9 They grow rapidly on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 30°C and produce woolly to cottony, flat, spreading colonies. From the front, the colour of the colony may be white, cream, tan, salmon, cinnamon, yellow, red, violet, pink or purple. From the back, it may be colourless, tan, red, dark purple or brown.10

Hyaline septate hyphae, conidiophores, phialides, macroconidia and microconidia are observed microscopically.10 Macroconidia (3−8×11−70 μm) are produced from phialides on unbranched or branched conidiophores. They are two or more celled, thick‐walled, smooth, and cylindrical or sickle‐(canoe‐)shaped. Macroconidia have a distinct basal foot cell and pointed distal ends. They tend to accumulate in balls or rafts. Microconidia (2−4×4−8 μm), on the other hand, are formed on long or short simple conidiophores. They are one‐celled (occasionally two‐celled or three‐celled), smooth, hyaline, ovoid to cylindrical and arranged in balls (occasionally occurring in chains).10Fusarium differs from Acremonium, Lecythophora and Phialemonium in having macroconidia.11

Besides being a common plant pathogen, Fusarium is also one of the emerging causes of opportunist by mycoses.10,12 It may exist in the soil of potted plants in hospitals. These plants constitute a hazardous mycotic reservoir for nosocomial fusariosis.13Fusarium species are causative agents of superficial and systemic infections in humans. Infections due to Fusarium species are collectively referred to as fusariosis. Trauma is the major predisposing factor for development of cutaneous infections due to Fusarium strains. Disseminated opportunist infections, on the other hand, develop in immunosuppressed hosts, particularly in neutropenic patients and those undergoing transplants.14,15Fusarium infections from solid organ transplantation tend to remain local and have a better outcome compared with those that develop in patients with haematological malignancies and patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation.16

Keratitis,17 endophthalmitis,18 otitis media,19 onychomycosis,20 cutaneous infections (particularly of burn wounds, mycetoma),21 sinusitis,22 pulmonary infections,23 endocarditis, peritonitis, central venous catheter infections, septic arthritis, disseminated infections10,12 and fungaemia24 due to Fusarium species have been reported.

Fusarium is one of the most drug‐resistant fungi. The only antifungal drugs that yield relatively low minimal inhibitory concentrations for Fusarium are amphotericin B, voriconazole25 and natamycin.21Fusarium infections are difficult to treat, and the invasive forms are often fatal. Amphotericin B alone or in combination with flucytosine or rifampin is the most commonly used antifungal drug for treatment of systemic fusariosis.16

Being a pathogen of the urinary tract infection, Fusarium has not been discussed in the English literature yet. Fusariosis of the urinary tract in this patient might have resulted from ascending infection due to urostasis produced by nephrolithiasis. The best therapeutic method for these patients is to resolve the underlying urolithiasis. In conclusion, Fusarium may be a pathogen of the urinary tract infection, particularly when urolithiasis is present.

Take‐home messages

Fusarium may be the pathogen of the urinary tract infection, particularly when urostasis is present.

Thus, resolving the urostasis is the best therapeutic method for these patients.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grant DTCRD94(2)‐08 from the Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi General Hospital, Chiayi County, Taiwan. The present study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital.

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Krcmery S, Dubrava M, Krcmery V., Jr Fungal urinary tract infections in patients at risk. Int J Antimicrob Antigen 199911289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho M, Guimaraes C M, Mayer J R., Jret al Hospital‐associated funguria: analysis of risk factors, clinical presentation and outcome. Braz J Infect Dis 20015313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kauffman C A, Vazquez J A, Sobel J D.et al Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis 20003014–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise G J, Silver D A. Fungal infections of the genitourinary system. J Urol 19931491377–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeFelice R, Wieden M A, Galgiani J N. The incidence and implications of coccidioidouria. Am Rev Respir Dis 198212549–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kueter J C, MacDiarmid S A, Redman J F. Anuria due to bilateral ureteral obstruction by Aspergillus flavus in an adult male. Urology 200259601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mukunyadzi P, Johnson M, Wyble J G.et al Diagnosis of histoplasmosis in urine cytology: reactive urothelial changes, a diagnostic pitfall. Case report and literature review of urinary tract infections. Diagn Cytopathol 200226243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robson A M, Craver R D.Curvularia urinary tract infection: a case report. Pediatr Nephrol 1994883–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitt J I, Hocking A D, Bhudhasamai K.et al The normal mycoflora of commodities from Thailand. 2. Beans, rice, small grains and other commodities. Int J Food Microbiol 19942335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Hoog G S, Guarro J, Gene J.et alAtlas of clinical fungi. 2nd edn. Vol 1 Utrecht, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, 2000

- 11.Sutton D A, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. eds. Guide to clinically significant fungi. 1st edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1998

- 12.Ponton J, Ruchel R, Clemons K V.et al Emerging pathogens. Med Mycol 200038225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Summerbell R C, Krajden S, Kane J. Potted plants in hospitals as reservoirs of pathogenic fungi. Mycopathologia 198910613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vartivarian S E, Anaissie E J, Bodey G P. Emerging fungal pathogens in immunocompromised patients: classification, diagnosis, and management. Clin Infect Dis 199317S487–S491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austen B, McCarthy H, Wilkins B.et al Fatal disseminated fusarium infection in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in complete remission. J Clin Pathol 200154488–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampathkumar P, Paya C V. Fusarium infection after solid‐organ transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 2001321237–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanure M A, Cohen E J, Sudesh S.et al Spectrum of fungal keratitis at Wills Eye Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cornea 200019307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louie T, el Baba F, Shulman M.et al Endogenous endophthalmitis due to Fusarium: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 199418585–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadhwani K, Srivastava A K. Fungi from otitis media of agricultural field workers. Mycopathologia 198488155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta A K, Summerbell R C. Combined distal and lateral subungual and white superficial onychomycosis in the toenails. J Am Acad Dermatol 199941938–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotowa N A, Shadomy H J, Shadomy S. In vitro activities of polyene and imidazole antifungal agents against unusual opportunistic fungal pathogens. Mycoses 199033203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schell W A. Histopathology of fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin N Amer 200033251–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rolston K V I. The spectrum of pulmonary infections in cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol 200113218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacicova G, Spanik S, Kunova A.et al Prospective study of fungaemia in a single cancer institution over a 10‐year period: aetiology, risk factors, consumption of antifungals and outcome in 140 patients. Scand J Infect Dis 200133367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinel‐Ingroff A. In vitro fungicidal activities of voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B against opportunistic moniliaceous and dematiaceous fungi. J Clin Microbiol 200139954–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]