Abstract

Background

Community follow-up is often inadequate for patients discharged from hospital following commencement of PEG tube feeding.

Objective and methods

We performed a postal questionnaire to assess if patients/carers were trained in the care of the PEG tube pre-discharge and whether appropriate community follow-up was in place.

Results

Of 166 PEG tubes inserted during the study period, 66 patients were alive at least 6 months following PEG tube insertion. Response rate was 44% (29 of 66 patients). Of the 29 respondents, 21 (72%) had been taught how to manage the tube, feeds and feeding pumps prior to discharge; 17 (59%) had their swallow re-assessed following PEG tube insertion and 16 (55%) patients were able to take some food or liquids by mouth. Twenty-four (83%) patients had had dietetic assessment following discharge. Fifteen patients had encountered problems with the PEG tube, 14 of whom knew who to contact in the event of a problem, all of which were resolved. In six of the 14 cases the respondent felt that the experience was not satisfactory for the patient/carer and that the resolution of PEG-related problems could be improved. In 9 (31%) cases the PEG tube had been removed.

Conclusions

Over two-thirds of patients/carers had been trained regarding PEG tube care. As expected, dietetic follow-up was in place for the majority of patients. Approximately one third of patients had had their PEG tube removed. Ongoing PEG tube feeding may not be required in all of the remaining patients. Most PEG tube problems were resolved although there is still scope to improve the PEG follow-up service.

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies (PEGs) are an established supportive treatment for a variety of medical conditions including stroke, cystic fibrosis and neurological disorders affecting swallowing. Outpatient follow-up of patients who have had PEG tubes inserted is often inadequate and variable in different institutions. We carried out a postal questionnaire of patients/carers of patients who had a PEG tube inserted in our hospital at least six months previously to determine whether training had been given to the patient/carer pre-discharge and to determine what community follow-up was in place.

METHODS

All patients who had a PEG tube inserted in the Belfast City Hospital between 1st October 2000 and 31st December 2004 were identified from an endoscopic database. The Patient Administration System was reviewed to determine which patients had died since their PEG tube insertion, so that a questionnaire was not sent to them. A postal questionnaire was posted out at least six months following the latest PEG tube insertion. Non-responders were sent a second questionnaire six weeks after the first questionnaire had been sent. Medical charts of respondents were reviewed to identify if PEG tube training had been given pre-discharge and details regarding PEG feeding if this had subsequently been discontinued.

RESULTS

Of 166 patients (84 male; mean age 70.0 years) who had PEG tubes inserted, 66 (31 male; mean age 66.2 years) were still alive at least six months following PEG tube insertion with a median follow-up of 25.7 months (range 0.5 – 4.6 yrs). Of the 100 patients (53 male; mean age 72.4 years) who were identified as deceased, 31 had died within 30 days following PEG tube insertion, giving a 30-day mortality of 18.7%. Seventy-one patients had died within six months of PEG tube insertion, giving a 6-month mortality of 42.8%.

Twenty-nine of 66 completed questionnaires were returned (response rate 44%). The respondent was the patient in six cases (one male) and the main carer in 23 cases (five male). The mean length of time the PEG tube had been in-situ was 19.5 months (based on 24 responses). Of the 29 respondents, 19 (65%) indicated that they had been taught how to manage the tube, feeds and feeding pumps prior to discharge; 17 (59%) had their swallow re-assessed following PEG tube insertion and 16 (55%) patients were able to take some food or liquids by mouth. Twenty-four (83%) patients had had dietetic assessment following discharge.

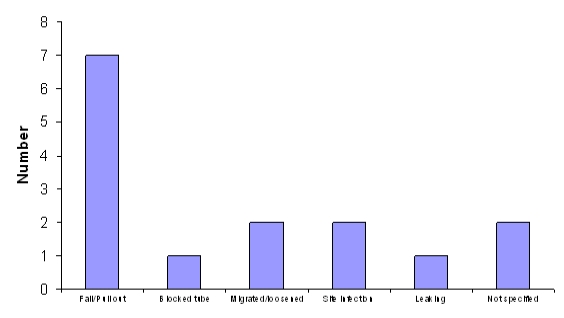

Fifteen (52%) patients had encountered problems with the PEG tube, 14 of whom knew who to contact in the event of a problem, all of which were resolved. In six of the 14 cases the respondent felt that the experience was not satisfactory for the patient/carer and that the resolution of PEG-related problems could be improved. The main problems encountered were PEG tube falling out (n=7); PEG site infection (n=2), migration / loosening of the PEG tube (n=2) and tube blockage (n=1) (Fig 1). Five respondents (17%) indicated that the PEG tube had subsequently been removed.

Fig 1.

PEG tube problems encountered following discharge

Following review of the medical records, the indications for PEG tube insertion in the 29 respondents are given in Table I. Six patients were identified as having their PEG tube removed from review of the medical notes, of whom four had not been clearly identified from the returned questionnaires, giving a total of nine patients (31%) in whom PEG tube feeding had been discontinued. The reasons identified in these nine patients were return of normal swallow reflex (n=8) [stroke in three; aspiration pneumonia in three; subdural haematoma in one; Parkinson's disease in one] and resolution of vomiting in gastroparesis (n=1). The PEG tube feeding was discontinued after a mean period of 5.4 months (range 1-12 months), by medical staff in five cases and the Nutrition Nurse Specialist in one case. Of the 19 cases in which PEG tube training was recalled by the patient/carer, documentation of training was confirmed on review of medical notes in six patients. In two further cases, training was documented in the medical notes, but the patient/carer did not recall this on the returned questionnaire, giving a total of 21 (72%) patients/carers who received training. No documentation of training was identified in 18 cases and three further patients were discharged to a Nursing Home familiar with PEG feeding. Training was given by Nursing staff (n=5), dietitian (n=1), Nutrition Nurse Specialist (n=1) and the Stoma Nurse (n=1).

Table I.

Indications for PEG tube insertion in 29 respondents

| Indication | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Stroke | 13 | 46 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 4 | 14 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 4 | 14 |

| Parkinson's disease | 3 | 10 |

| Sub-dural haematoma | 2 | 7 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 | 3 |

| Gastroparesis | 1 | 3 |

| Tongue carcinoma | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 29 | 100 |

DISCUSSION

In secondary care the main emphasis is on appropriate selection of patients for PEG tube insertion, the safe insertion of PEG tubes and the training of the patient/carer in the management of the PEG tube, including the correct use of the feeds and the feeding pumps1. Education of patients and caregivers by a multidisciplinary nutrition support team has been shown to promote independence and can limit subsequent demands on the service2. Due to limited resources there may be no formal care for PEG tube patients following discharge from hospital. Ideally all patients should have community follow-up by a dietician, speech and language therapist and an appropriately trained professional who can deal with problems and advise accordingly. Late recovery of swallow may occur following acute dysphagic stroke and these patients should have a follow-up swallowing assessment3. It has been proposed that a nurse specialist or dietician could establish a liaison service focusing on primary care and using hospital resources when appropriate4.

We performed a postal survey of patients/carers to assess if training on PEG tube care was given and to assess the degree of community follow-up and the availability of appropriate care should problems arise. PEG tube training was carried out in 21 (72%) patients. Documentation in medical notes is frequently inadequate and the fact that the absence of a record of PEG tube training in the medical notes is not categorical evidence that it had not taken place. In two cases the patients/carers did not recall training having taken place when it had been documented and this may be as a result of the long period of follow-up in this study (median 19.5 months). As expected, dietetic follow-up was in place for the majority of patients. However, in view of the fact that 16 patients were able to take some food or liquids and 17 had undergone follow-up assessment by a speech therapist, this raises the possibility that PEG tube feeding may not still be required in all of the remaining patients. Thirty-one percent of patients had had their PEG tube removed which is slightly higher than previous studies, and may reflect the indications present, some of which may be temporary (gastroparesis, aspiration pneumonia)5.

To date it has been difficult to optimise the widespread availability of appropriately trained personnel in the community who can resolve PEG tube problems, as and when they arise. General Practitioners and district nurses may not have been trained in the insertion of balloon gastrostomy replacement tubes and this often results in patients attending busy Accident and Emergency departments when the PEG tube falls out, due the lack of adequately trained personnel in the community. Since PEG tube feeding is increasingly used following stroke, there is an urgent need for such training to be performed. Alternative appropriate personnel include community nurse specialists or nutrition nurse specialist, based in secondary care, but providing a service to the community.

Nutrition clinics have been proposed as a means of continually reviewing patients following PEG tube insertion. This requires a multi-disciplinary approach from dieticians, speech and language therapists, nutrition nurse specialist and medical endoscopists. It would have huge resource implications but it is one possible way to ensure that PEG tubes are maintained adequately and that patients have ongoing assessment to determine if ongoing PEG tube feeding is the best feeding option for the individual. One study has reported that it does not increase costs and does improve quality of care for these patients6. To date nutrition clinics have not been set up in many hospitals.

We performed a questionnaire to assess what follow-up was in place for patients in the community following discharge after PEG tube insertion. This study is somewhat limited by the poor response rate (44%) and the long follow-up period, which may limit recall by patients/carers. We decided to limit our postal questionnaire to those patients who were still alive at least six months following PEG tube insertion, and this limited the number in the study population under consideration. Whilst we have demonstrated that there is currently a reasonable quality of follow-up for these patients following discharge from hospital, further improvements in aftercare of these patients following PEG tube insertion could be made.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathus-Vliegen LM, Koning H. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and gastrojejunostomy: a critical reappraisal of patient selection, tube function and the feasibility of nutritional support during extended follow-up. Gastrointestl Endosc. 1999;50(6):746–54. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koulentaki M, Reynolds N, Steinke D, Tait J, Baxter J, Vaidya K, et al. Eight years' experience of gastrostomy tube management. Endoscopy. 2002;34(12):941–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James A, Kapur K, Hawthorne AB. Long-term outcome of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding in patients with dysphagic stroke. Age Ageing. 1998;27(6):671–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.6.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders DS, Carter MJ, D'Silva J, McAlindon ME, Willemse PJ, Bardham KD. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a prospective analysis of hospital support required and complications following discharge to the community. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(7):610–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholson FB, Korman MG, Richardson MA. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a review of indications, complications and outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(1):21–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott F, Beech R, Smedley F, Timmis L, Stokes E, Jones P, et al. Prospective, randomized, controlled, single-blind trial of the costs and consequences of systematic nutrition team follow-up over 12 months after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Nutrition. 2005;21(11-12):1071–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]