In the summer of 2006, a previously healthy 16 year old individual presented to the local Accident and Emergency Department, of a Northern Ireland hospital, with a 1.5cm diameter abscess over the left great toe, surrounded by cellulitis. The lesion had failed to respond to oral flucloxacillin prescribed by the family doctor. Apart from trauma to the toe three weeks previously, the patient had no significant past medical history and no risk factors for the acquisition of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The lesion required incision and drainage on two occasions. Culture of pus revealed MRSA and treatment was changed to oral doxycyline. Phenotypically, the organism behaved unusually, in that it was sensitive to ciprofloxacin, unlike the majority of other MRSA isolates seen. Detailed molecular work-up of the isolate demonstrated that it carried the Panton Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) gene locus and belonged to subclass IV of the Staphylococcal Chromosomal Cassette (SCCmec), a typical microbiological characteristic of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA).

To date, there has been an extensive awareness of MRSA within healthcare facilities, particularly hospitals. More recently, there has been increased reporting of MRSA occurring in the community amongst healthy individuals who have no hospital association.1 Most recently, the first nosocomial outbreak of community-associated MRSA, has been described in the West Midlands.2 Eight cases of Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) positive community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) were identified among individuals in a hospital and their close household contacts, of whom four individuals developed an infection, which was fatal in two cases. Transmission of the CA-MRSA strain appeared to have occurred on two separate wards and went undetected until a fatal case was examined in detail.

These organisms are termed CA-MRSA (community-associated MRSA) and differ significantly from healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA). Although all are Staphylococcus aureus, they have distinct epidemiological and microbiological characteristics which are summarised in Tables I and II. Notably CA-MRSA are more likely to produce PVL, a cytotoxin that causes leucocyte destruction and tissue necrosis, than HA-MRSA.

Table I.

Comparison of clinical, epidemiological and microbiological characteristics of community-associated MRSA

| Characteristic | Staphylococcus aureus | Healthcare-associated-MRSA (HA-MRSA) | Community-associated-MRSA (CA-MRSA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population affected | immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals in the community. | Hospital/healthcare/nursing home patients/residents elderly, preterm neonate immunocompromised neonates. | Usually young healthy individuals in the community. |

| Those who have no risk factors for acquisition of HA-MRSA. | |||

| Individuals in prisons, military personnel, athletic population (especially those involved in combat and ball sports), male homosexuals, ethnic populations (native American Indians, Hawaiian islanders, Alaskan native people). | |||

| Site of infection | Predominantly wound, bacteraemia, (including infective endocarditis), enterotoxin-mediated food-poisoning. | Bacteraemia & wound infections Also symptomatic infections of respiratory and urinary tracts. | Mainly skin (abscesses and cellulitis, furunculosis, severe skin and soft tissue infections (sSSTIs). In severe cases, septic shock & bacteraemia. |

| Risk factors | Colonisation with S. aureus, trauma, body piercing, drug abuse. | Indwelling devices, catheters, lines, haemodialysis, prolonged hospitalisation, long term antibiotic use. | Close physical contact, abrasion injuries, activities associated with poor communal hygiene (e.g. sharing towels) |

| Transmission | Patients' own skin flora |

|

person-to-person shared facilities (e.g. Sports equipment. towels, pools, etc) environment |

| Microbiological characteristics | |||

| Susceptibility to methicillin | Yes | No | No |

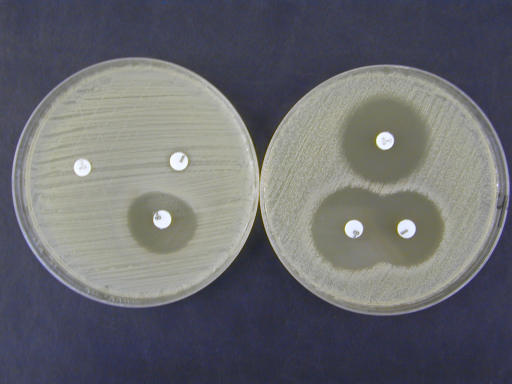

| Susceptibility to other antibiotic agents (fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, erythromycin, clindamycin) (see Figure 1) | Yes | No | Yes |

| Presence pvl gene locus | Variable (usually limited) | low (<5%) | high (>95%) |

| SCCmecA type | not present | predominantly subclasses I, II or III | Mainly IV (& subtypes a-h), V |

| Treatment | Oral or IV flucloxacillin | Oral: doxycyline IV: vancomycin/teichoplanin/daptomycin | clindamycin or co-trimethoxazole |

Table II.

Key points associated with community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). (Adopted from Elston1)

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Epidemiological | CA-MRSA was first described over a decade ago and only recently emerged as a significant clinical and virulent Gram +ve pathogen in the US. |

| It has not been described in Northern Ireland until now | |

| Approximately 85% of CA-MRSA infections present in skin, usually with abscesses, cellulitis and/or folliculitis. | |

| Elsewhere, they can mimic a spider-bite and consider this if patient has recently returned from an endemic area, where spider bites are common, e.g. USA. | |

| Different epidemiology to HA-MRSA. Mainly present in young health individuals with no risk factors for the acquisition of MRSA. High-risk populations include individuals in prisons, military personnel, athletic population (especially those involved in combat and ball sports), male homosexuals, ethnic populations (native American Indians, Hawaiian islanders, Alaskan native people) and children in playgroups/nurseries. | |

| Presentation | Young otherwise healthy individual in high-risk population, As detailed above, with spontaneous abscess, cellulitis and a collection of pus |

| Treatment | Surgical drainage of skin abscess. Many patients respond to drainage alone. |

| Seriously ill patients should be hospitalized | |

| Most infections in clinically well patients are treated appropriately on an out-patient basis with oral antibiotics | |

| Microbiological | Taxonomically, all organisms are Staphylococcus aureus. |

| Virtually all CA-MRSA are positive for the Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) gene locus | |

| Most CA-MRSA isolates belong to SCCmec IV (+ subclasses) and V | |

| No simple laboratory test for microbiological confirmation of CA-MRSA status. Requires testing with PVL and SCCmec PCR techniques, usually at specialist or reference laboratory | |

| Microbiological suspicion of the presence of CA-MRSA should be given to MRSA isolates which are sensitive to ciprofloxacin | |

| All suspect ciprofloxacin-sensitive MRSA isolates should be sent to Dr Angela Kearns, Staphylococcus aureus Reference Laboratory, Health Protection Agency, 61 Colindale Avenue, LONDON, for molecular confirmation and characterization. |

Fig 1.

Relative antibiotic sensitivity of community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) (right plate) and resistance of healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) (left plate) to ciprofloxacin, erythromycin and clindamycin by standard disk diffusion assay (Photo: Courtesy of Mr. Lester Crothers and Mr. Mark McCalmont, Northern Ireland Public Health Laboratory, Department of Bacteriology, Belfast City Hospital)

Community-associated MRSA has recently emerged in the US as a clinically significant and virulent pathogen. It is associated with serious skin and soft tissue infections, particularly in young healthy individuals in the community and those who have no risk factors for acquisition of HA-MRSA.1 Several reports have described this organism in individuals in prisons, military personnel, athletes (especially those involved in combat and ball sports, including rugby, American football, wrestling, fencing), male homosexuals and ethnic populations (native American Indians, Hawaiian islanders, Alaskan native people). Risk factors for its acquisition include close physical contact, abrasion injuries and activities associated with poor communal hygiene (e.g. sharing towels). This organism is now emerging in several European countries, including the UK.

While HA-MRSA cause heterogeneous invasive infections, CA-MRSA is usually limited to skin and soft tissue infections, particularly folliculitis, pustular lesions and abscesses. Less commonly, CA-MRSA can cause severe and rapidly fatal infections such as necrotizing pneumonia and necrotizing fasciitis.

Therapy for CA-MRSA infections presents a challenge for the clinician. They are resistant to the agents most likely to be prescribed for S. aureus infections in the community i.e. β-lactams. Small abscesses may respond to incision and drainage alone but antibiotic treatment is indicated if the patient does not respond rapidly. Current UK guidance suggests consideration of doxycycline and rifampicin for such infections. Patients should also be screened for CA-MRSA carriage and a decolonization schedule, as employed for HA-MRSA used where carriage is demonstrated. For severe and overwhelming infections caused by these organisms, antimicrobial agents may be ineffective because the patient receives the treatment too late. Such patients require full intensive care support. Optimal antimicrobial agent therapy is unknown but combination therapy may be helpful. Agents which have been used in this setting include vancomycin, rifampicin, cotrimoxazole, linezolid and clindamycin. The latter two agents have the advantage of suppression of bacterial toxin production. Finally, the addition of intravenous immune globulin (which contains anti PVL antibodies) should be considered in fulminant cases.

Microbiologically, CA-MRSA are difficult to differentiate from HA-MRSA and at present, there is no phenotypic testing method available in most primary diagnostic clinical microbiology laboratories in the UK, that can reliably distinguish between these two organisms, for definitive identification purposes.

In a recent study adopting molecular (PCR) techniques to aid in their differentiation, our group have identified 4/224 (1.8%) consecutive MRSA isolates, as CA-MRSA, which had been classified generically as MRSA.3 Therefore, given the important clinical and epidemiological differences between these types of MRSA, it is important that local physicians have a comprehension of CA-MRSA and that any presumptive CA-MRSA isolates that begin to emerge in Northern Ireland are confirmed and further characterized, so that we can quickly gain an understanding of the diversity/relatedness of such isolates to help guide local guidelines/practice and interventions to minimize its occurrence.

In conclusion, this initial report of CA-MRSA in Northern Ireland, from a 16 year old patient, is typical of CA-MRSA presentation. Firstly, it occurred in a young otherwise healthy individual, with a history of recent trauma. Secondly, the signs and symptoms, namely cellulitis with a large abscess, requiring drainage, was consistent with CA-MRSA skin/soft tissue infection. Thirdly, the resulting cultured MRSA was unusual, in that it was sensitive to ciprofloxacin on in vitro antibiotic susceptibility testing, suggesting the presence of a CA-MRSA organism. Thus, GPs, dermatologists and A&E physicians should beware of the emergence of CA-MRSA locally and should consider and manage such an organism in patients presenting with such symptoms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elston DM. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Communicable Disease Report Weekly. News. Hospital-associated transmission of Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) positive community-associated MRSA in the West Midlands. Communicable Disease Report Weekly [CDR Weekly] 2006;16(50) 1 Available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/cdr/archives/archive06/News/news5006.htm. [Last accessed February 2007]

- 3.Maeda Y, Millar BC, Loughrey A, McCalmont M, Nagano Y, Goldsmith CE, et al. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA): what are we missing? J Clin Path. 2007 doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.046011. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]