Abstract

The plasminogen activator inhibitors (PAIs) play critical roles in regulating hemostatic and invasive functions of trophoblasts through suppression of plasmin-dependent fibrinolysis and extracellular matrix degradation. The expression of PAI-1 is increased under hypoxic conditions, although the mechanism remains incompletely understood. In the current study we used HTR-8/SVneo cells, a first trimester extravillous trophoblast cell line, and siRNA technology to examine the role of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs)−1α and −2α in the regulation of PAI-1 expression. Using serum-containing and serum-free media culture media it was initially noted that levels of PAI-1, but not PAI-2 protein, were markedly induced by hypoxic (2−3% oxygen) treatment. Under hypoxic conditions, Western blotting revealed that the presence of siRNAs to HIF-1α and HIF-2α suppressed expression of their respective proteins, whereas treatment with non-targeting and cyclophilin B siRNAs did not. Importantly, incubation with siRNA to HIF-1α or HIF-2α alone reduced PAI-1 protein levels to a similar extent, with the combined treatment inducing a more profound effect. The presence of HIF siRNAs reduced levels of PAI-1 mRNA as measured by quantitative real-time PCR, indicating that HIF-1α and HIF-2 α regulate PAI-1 expression at a transcriptional level. These results indicate that both HIF-1α and HIF-2α play important and similar roles in hypoxia-mediated stimulation of PAI-1 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells. Our findings provide insight into the physiological regulation of trophoblast PAI-1 expression in early pregnancy when placental oxygen levels are low, as well as a mechanism for over-expression of placental PAI-1 noted in pregnancies with preeclampsia.

Keywords: Placenta, plasminogen activators, hypoxia-inducible factor, trophoblast

INTRODUCTION

Successful placentation and maintenance of pregnancy requires that invasive and hemostatic processes in trophoblasts are tightly regulated [1-4]. The plasmin/plasminogen activator system plays a key role in modulating these pathways at the maternal-fetal interface [2,3]. In trophoblasts as in other cell types, plasmin-dependent fibrinolysis is controlled through the action of tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), whereas urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) mediates plasmin-associated degradation of the extracellular matrix, a requisite for cellular invasion [5,6]. Plasminogen activator inhibitors, (PAIs), members of the serpin (serine protease inhibitor) family of protease inhibitors, suppress uPA and tPA activity and limit plasmin generation [5,7]. PAI-1, a 52 kD protein, was originally described as an endothelial cell protein [8], but later reports revealed that it was synthesized by several cell types, including trophoblasts and decidual cells [9-11]. PAI-2 is expressed at extremely high levels in placental tissue [12], but its secretion in several cell types including trophoblasts may be limited by a non-cleaved secretion signal that appears to be inefficient by design [13]. The binding affinity of tPA for PAI-1 is 1,000-fold that of PAI-2 [5,6], indicating that PAI-1 plays a more critical role in the regulation of fibrinolysis. Conversely, both PAIs are suggested to play major roles in uPA-dependent invasion [3,6]. Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization studies have localized PAI-1 in human placenta mainly to extravillous or invasive trophoblasts, whereas PAI-2 is expressed at higher level by syncytiotrophoblasts (i.e. the outer cell layer bathed by maternal blood) [9,14-16]. Pathological up-regulation of PAI-1 levels in syncytiotrophoblasts [14,15] is suggested to promote increased intervillous fibrin deposition and placental infarction (villous collapse) noted in pregnancies associated with preeclampsia (PE) [14-18]. A direct role of PAI-1 in TNF-α-mediated inhibition of trophoblast migration and invasion was demonstrated using PAI-1 blocking antibodies in villous explants from first trimester placenta and a trophoblast cell line [19,20].

Previous work showed that PAI-1 expression is increased under hypoxic conditions in several cell types including trophoblasts [21,22]. The PAI-1 gene, like several other hypoxia-responsive genes, has a hypoxia response element (HRE) in its promoter through which hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) induces transcription [23]. HIF is a heterodimer composed of either HIF-1α or HIF-2α and HIF-1β (ARNT) subunits, all of which contain basic helix-loop-helix motifs and Per-ARNT-Sim domains [24]. Regulation of HIF activity is achieved through oxygen degradation domains in HIF-1α and HIF-2α (24). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is hydroxylated by prolyl hypdroxylase, promoting ubiquitination of the HIF heterodimer by the Von-Hippel-Lindau complex which rapidly targets HIF for degradation by the proteasome [25]. Under low concentrations of oxygen, prolyl hydroxylase activity decreases, HIF-α is stabilized and binds to the constitutively expressed HIF-1β, and the complex translocates to the nucleus [25]. Although HIF-1α and HIF-2α may both participate in enhancing the expression of a particular gene under hypoxic conditions, preferential cell-type specific involvement of one of the HIF-α subunits was generally observed [26-28].

In light of the importance of PAIs in trophoblast function and the observed stimulation of PAI-1 levels by hypoxic treatment, the goal of the current study was to assess the relative contributions of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the modulation of PAI expression in trophoblasts under hypoxic conditions. We used small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology to suppress HIF-1α and/or HIF-2α expression in the HTR-8/SVneo cell line. It is well established that siRNAs (19−21bp RNA fragments) suppress gene expression following binding to specific complementary mRNA, thereby promoting their degradation [29]. HTR-8/SVneo cells, derived from first trimester placenta, express an extravillous trophoblast phenotype and maintain characteristics of the non-immortalized HTR-8 parent cell line including proliferative and invasive potential as well as hormone responsiveness [30]. In addition, our group and others have previously demonstrated that PAI-1 expression in this cell line was induced by hypoxic treatment as well as by glucocorticoid and TGF-β [22,31]. Previous studies have used siRNAs to down-regulate HIF-1α and/or HIF-2α expression in cancer cell lines [26,28], but not in trophoblasts or trophoblast cell lines, and their effect on PAI levels was not examined. This study is relevant to PAI regulation in early pregnancy when the placenta is exposed to relatively hypoxic conditions (2−3% O2) in the first 10 weeks of gestation [32], as well as to pregnancies complicated by PE which is associated with prolonged hypoxia and aberrant PAI-1 expression at the maternal-placental interface [1,4,14,15].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Tissue culture media was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Bovine sera were obtained from Gemini Bio-Products (Calabasas, CA). Laboratory plasticware was obtained from Falcon, Becton-Dickinson Labware (Lincoln Park, NJ). ITS+, a mixture containing insulin, transferrin and selenium, was obtained from Collaborative Research-Becton Dickinson (Bedford, MA). The PAI-1 and PAI-2 ELISA kits were from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). Other reagents used in cell culture, Western blotting, and quantitative real-time procedures were obtained from previously described sources [13,33,34]. Materials for siRNA studies were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

Methods

Cell culture

HTR-8/SVneo cells were supplied by Dr. Charles Graham (Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario). They are a cell line obtained following immortalization of a first trimester short-lived extravillous trophoblast cell line HTR-8 after transfection with SV40 large T antigen followed by selection for neomycin resistance [30]. These cells share the phenotype and function of HTR-8 cells including responsiveness to TGF-β as well as the absence of a transformed phenotype (e.g. anchorage-independent growth or tumorigenicity in nude mice) [30,35]. In the present study, HTR-8/SVneo cells were maintained and passaged in RPMI medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum and 1 mM glutamine (i.e. FBS medium) prior to experimentation. For all experiments, cells were trypsinized and plated in triplicate wells for each experimental condition, at a density of 2.5 ×105 cells per 6 well plate in FBS medium under normoxic conditions (21% O2). Experiments were initiated after 2 or 3 days at which time cells reached 60−70% confluency. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5%CO2/95%air.

Regulation of PAIs by hypoxic treatment

Cells were washed once with PBS, and fresh FBS medium or serum-free medium containing a 1:1 mixture of phenol red-free Ham's F12:Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium containing ITS+ (a supplement utilized to obtain a final concentration of insulin of 6.25 μg/ml, transferrin 6.25 μg/ml, selenous acid 6.25 ng/ml, bovine serum albumin 1.25 mg/ml, and linoleic acid 5.35 μg/ml) [31] was added. In one group, normoxic incubation was continued for 4, 8, 24 and 48 h. A second group of cells were maintained for these time periods under hypoxic conditions as we have previously described [33]. Briefly, cells was incubated in sealed plexiglass chambers (Belleco Glass Co., Vineland, NJ) containing an oxygen gas analyzer (Hudson RCI, Temecula, CA) and a beaker of water to maintain humidity. Air in the chambers was purged with 5% CO2/95% N2 for 10 min after the oxygen meter read 0 to 1% O2. The sealed chambers were then placed in a 37°C incubator for the indicated time. Under these conditions a reading of 1−3% O2 was maintained for at least 48 h [33]. After the designated time in culture, supernatants were removed, cells were rapidly washed on ice with cold PBS and then lysed with 100 μl of a solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM NaF, 1%Triton X-100, 0.1 % SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, with a protease inhibitor cocktail containing 10 μg/ml each of pepstatin, leupeptin, aprotinin, soybean trypsin inhibitor, and phenylmethylsulfonylflfluoride (i.e. lysis buffer). Cell layers were scraped, vortexed, placed on ice for 10 min, centrifuged (7000 x g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Levels of PAI-1 and PAI-2 in the culture media were measured by ELISA according to information provided by the manufacturer. Levels of PAIs in culture media were determined in triplicate wells and were normalized to cell protein using the DC Protein Assay from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). Concentrations of these compounds at the indicated time points reflect cumulative levels since media were not replaced during the experiment. For each time point studied, the effect of hypoxic treatment on PAI-1 expression was examined in 5 to 8 independent experiments using both FBS medium and serum-free medium. The effect of hypoxic treatment on PAI-2 levels was examined in 3 or 4 independent experiments for each time point and culture medium studied. In this series of experiments, and all others, results are expressed as a mean + SE. Effect of hypoxic treatment at each time point studied was compared to its normoxic control by Student's t test.

siRNA studies

For these studies, cells plated in FBS medium were washed once with PBS and transfected with 100 nM siRNA duplexes to: HIF-1α (sense, GGACACAGAUUUAGACUUGUU; antisense, CAAGUCUAAAUCUGUGUCCUU); HIF-2α (sense, GCAAAUGUACCCAAUGAUAUU; antisense, UAUCAUUGGGUACAUUUGCUU); 100 nM of both HIF-1α + HIF-2α siRNA; non-targeting siRNA (sequence not released, cat # D-001210−01−05) serving as a negative control; cyclophilin B siRNA (sequence not released, cat # D-001136−0105) serving as a positive control; or transfection reagent alone (i.e. mock transfection with DharmaFECT 1 Transfection Reagent, 4 μl reagent/100nM siRNA) in serum-free RPMI. The cells were transfected according to the Dharmacon protocol for 6-well plates. For all experiments each treatment was carried out in triplicate wells. Following addition of siRNA, cells were incubated for 30 min under normoxic conditions and then one group of cells was placed into a hypoxic chamber as described above. After 48 h, the chambers were opened and supernatants were immediately removed and stored at −20°C until further analysis of PAI levels by ELISA. Within 1 to 2 min of opening the hypoxia chamber, adherent cells were washed once with ice cold PBS, and harvested on ice for total protein and Western blot analysis with 100 μl lysis buffer (see above). The lysate was then vortexed for 30 sec and placed on ice for 10 min prior to centrifugation (7000 x g, 10 min, 4°C). Supernatants were stored at −80°C until further analysis. Results showing the effect of siRNA treatment on expression of PAI-1 levels in culture media are presented as a mean value + SEM from 4 to 8 independent experiments. Results were analyzed by ANOVA covering all treatments. Pair-wise comparisons were carried out using the Tukey test.

Western blotting

Western blotting was used to initially assess the time-dependent changes in expression of HIF-1α, HIF-2α and cyclophilin B expression under hypoxic conditions, and then to examine the effect of siRNA treatment on expression of these proteins. For these studies 25 μg of cell lysate from each condition was incubated for 5 min at 37°C with Laemelli sample buffer containing 50 μM of the reducing agent dithiothreitol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Electrophoresis was carried out using 4−15% Tris-HCl gradient gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were then transferred on ice to Hybond ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, England). The membranes were then blocked with 5% Carnation non-fat dry milk in a solution containing PBS and 2% Tween-20. Proteins were detected with mouse monoclonal antibodies to HIF-1α (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA), HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), and rabbit cyclophilin B antibody (Abcam Incorporated, Cambridge, MA) at dilutions of 1:250, 1:1000 and 1:2000, respectively. Cyclophilin B levels served as a loading control as well as a positive control for siRNA knock-down. Overnight incubation with primary antibody at 4°C was followed by a 1 h incubation with goat anti-mouse (1:5000) or goat anti-rabbit (1:15,000) horseradish secondary antibody conjugates (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate, Pierce, Rockford, IL). For quantitation of Western blotting results, intensities of bands for HIF-1α, HIF-2α and cyclophilin B on scanned autoradiographs were analyzed using NIH Image J software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and the level of HIF expression was normalized to that of cycophilin B. For the time course experiment shown in Figure 3, a Western blot from a single experiment is shown representing 3 identically conducted ones. For the HIF siRNA knockdown study shown in Figure 4, a single experiment representing 4 identically conducted ones is shown.

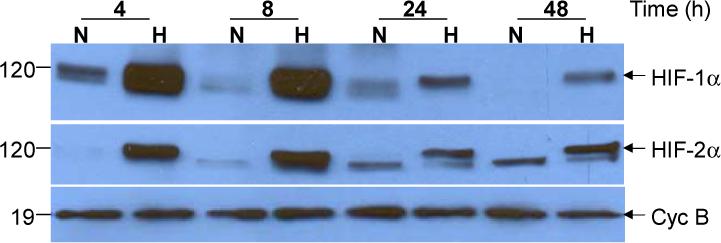

Figure 3.

Hypoxia-dependent induction of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

Cells were maintained for the indicated time under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions and levels of HIF-1α (Top Panel), HIF-2α (Middle Panel) and cyclophilin B Bottom Panel) were analyzed by Western blotting. The predominant hypoxia-responsive species for both HIFs was detected at a molecular weight of approximately 120 kD and is indicated by an arrow. A lower molecular weight, hypoxia-unresponsive species was also detected by the HIF-2α antibody at approximately 110 kDA. These blots are from a single experiment representing 3 identically conducted ones.

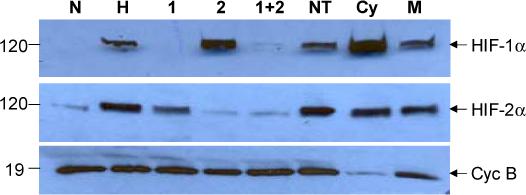

Figure 4.

Western blot of siRNA-mediated suppression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression.

HTR8/SVneo cells were maintained for 48 h under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions alone, or transfected under hypoxic conditions with the following siRNAs: 1, HIF-1α; 2, HIF-2α; 1+2, HIF-1α and HIF-2α; NT, non-targeting; Cy, cyclophilin B; M, mock transfection. Levels of HIF-1α (Top Panel), HIF-2α (Middle Panel), and cyclophilin B (Bottom Panel) were detected following Western blotting and immunodetection. These results were obtained in a single experiment representing 4 independently conducted ones.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Procedures for quantitative real-time PCR analysis are essentially as we have previously described [34]. Total cellular RNA was initially extracted from duplicate wells for each condition studied and purified with an RNAeasy minikit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Five μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with AMV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). A quantitative standard curve ranging from 500 pg to 250 ng of cDNA was created with the Roche Light Cycler (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) by monitoring the increasing fluorescence of PCR products during amplification. Once the standard curve was established, quantitation of unknowns was determined and adjusted to the expression of 18S RNA. Melting curve analysis was conducted to determine the specificity of the amplified products and to ensure the absence of primer-dimer formation. All products obtained yielded the correct melting temperature. Electrophoresis of amplified products revealed a single product of the expected size for PAI-1 (233 bp) and 18S RNA (333 bp), and DNA sequencing verified their identity. The following primers were synthesized and gel-purified at the Yale DNA Synthesis Laboratory, Critical Technologies: PAI-1 (forward, 5′-TGCTGGTGAATGCCCTCTACT-3′; reverse, 5′-CGGTCATTCCCAGGTTCT CTA-3′) and 18S RNA (forward, 5′-GAT ATGCTCATGTGGTGTTG; reverse, 5′-AATCTTCTTCAGTCGCTCCA-3′). Results shown in Fig. 5 are from a single experiment representing 3 identically conducted ones.

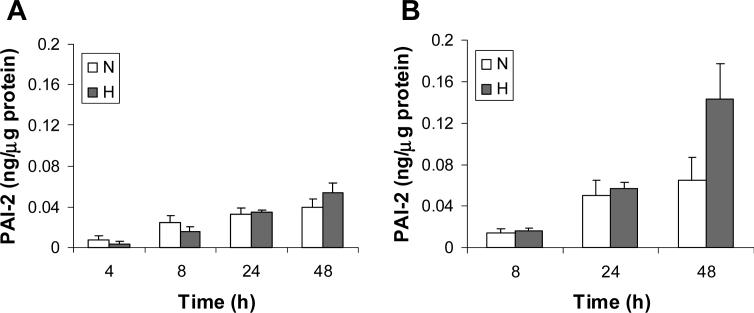

Figure 5.

Effect of HIF siRNA treatment on PAI-1 levels in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

HTR8/SVneo cells were incubated for 48 h under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions alone, or were maintained under hypoxic conditions with the following siRNAs: NT, non-targeting; Cyc, cyclophilin B; M, mock transfection; 1, HIF-1α; 2, HIF-2α; 1+2, HIF-1α and HIF-2α. Levels of PAI-1 in culture media were determined by ELISA and normalized to total cellular protein. Results are expressed as a mean + SE obtained in 4 to 8 independent experiments.

*P < 0.02 vs hypoxic treatment alone group

+P < 0.001 vs non-targeting and mock transfection groups

Statistics

Results are expressed as a mean + SE. Data were analyzed by Student's t test or ANOVA using SigmaStat software from Jandel Scientific (San Rafael, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Regulation of PAI-1 expression by hypoxic treatment

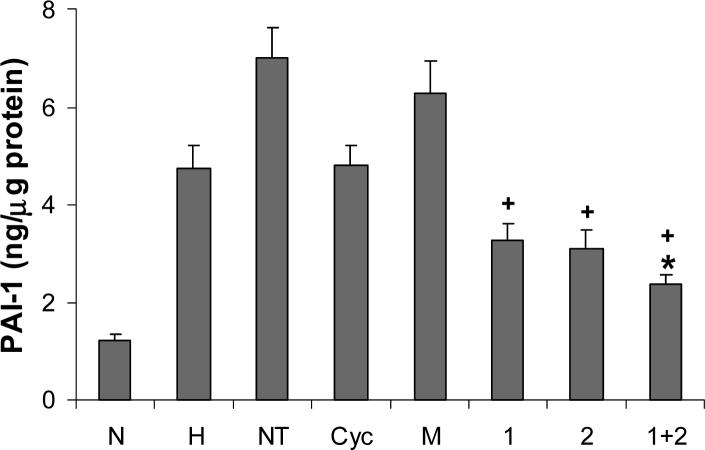

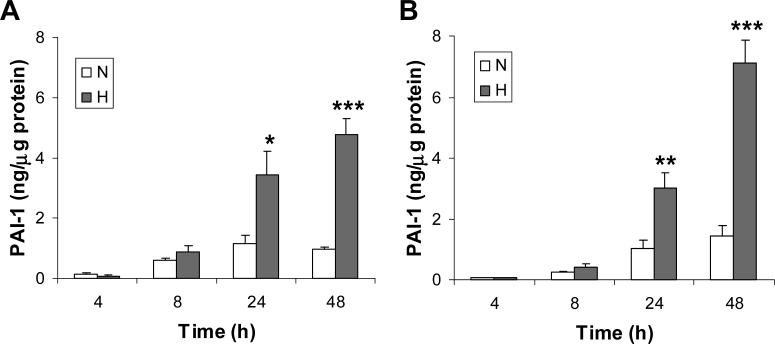

HTR-8/SVneo cells were incubated for 4, 8, 24 and 48 h under normoxic or hypoxic conditions and levels of PAI-1 and PAI-2 in culture media were determined by ELISA following normalization to total cellular protein. Experiments were conducted in serum-containing media and serum-free media to control for effects of endogenous serum factors. Using both media, we noted no significant change in PAI-1 levels following hypoxic treatment for 4 and 8 h (Fig. 1), whereas a significant 3- and 5-fold induction were noted at 24 and 48 h, respectively (serum-containing media, P < 0.05 at 24 h and P < 0.001 at 48 h; serum-free medium, P< 0.01 at 24 h and P < 0.001 at 48 h). Conversely, hypoxic treatment had no significant effect on PAI-2 levels under serum-containing or serum-free conditions at all time points studied (Fig. 2). The 2-fold induction in PAI-2 levels by hypoxic treatment noted only in serum-free medium at 48 h did not reach statistical significance. In addition, the PAI-1 levels in culture media were at least 10-fold that of PAI-2 for all conditions studied. These results indicate that PAI-1 is the major PAI released by HTR-8/SVneo cells, and its concentration in culture media is markedly enhanced by hypoxic treatment.

Figure 1.

Hypoxic treatment enhances PAI-1 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

HTR-8/SVneo cells were cultured in either serum-containing (Panel A) or serum-free (Panel B) media under normoxic (unfilled bars) or hypoxic (filled bars) conditions. At the indicated time points, the concentration of PAI-1 in culture media were analyzed by ELISA and normalized to total cell protein. Results are expressed as a mean + SE from 5 to 8 independent experiments for each time point studied.

*P < 0.05 vs normoxic control by Student's t test

**P < 0.01 vs normoxic group by Student's t test

***P < 0.001 vs normoxic group by Student's t test

Figure 2.

Effect of hypoxic treatment on PAI-2 levels in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

Cells were incubated in serum-containing (A) or serum-free (B) medium under normoxic (unfilled bars) or hypoxic (filled bars) conditions, and at the indicated time level of PAI-2 in culture media was determined by ELISA and normalized to cell protein. Results are presented as a mean + SE from 3 or 4 independent experiments at each time point studied.

Regulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression by hypoxic treatment

Since HIF is a critical regulator of hypoxia-dependent changes in gene expression [24], we then used Western blotting to examine the time course of hypoxia-dependent changes in cellular levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in HTR-8/SVneo cells. We noted that hypoxic treatment for 4, 8, 24 and 48 h markedly increased levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in cell extracts compared to normoxic controls at all time points studied (Fig. 3). The predominant, hypoxia-inducible HIF-1α and HIF-2α species was detected at a molecular weight of approximately 120 kDa (indicated by the arrows in the top and middle panels of Fig. 3), consistent with previous findings [36]. A lower molecular protein (∼110 kDA), unresponsive to hypoxic treatment, was also detected by antibody to HIF-2α. It is of note that maximal levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α were observed after 8 h of hypoxic treatment. Conversely, hypoxic treatment had no effect on the expression of cyclophilin B, a 19 kDa housekeeping gene. These studies indicate that induction of HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels by hypoxic treatment precedes stimulation of PAI-1 expression.

Use of siRNA to suppress HIF expression in HTR8/SVneo cells

Previous studies have used siRNA technology to down-regulate HIF expression in several cancer cell lines [26,28], but not in trophoblasts or trophoblast cell lines. Before evaluating the effect of HIF siRNAs on PAI-1 levels in HTR8/SVneo cells, it was necessary to determine the efficacy and specificity of suppression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression following siRNA treatment. HTR-8/SVneo cells were maintained for 48 h under normoxic conditions, under hypoxic conditions alone, or with siRNA to HIF-1α, HIF-2α, HIF-1 + HIF-2α, a non-targeting sequence, cyclophilin B, or transfection reagent (i.e. mock treatment). Levels of HIF-1α, HIF-2α and cyclophilin B expression in cell extracts were determined by Western blotting (Fig. 4). As expected, hypoxic treatment markedly enhanced levels of both HIF-1α (top blot) and HIF-2α (middle blot). Treatment with HIF-1α or HIF-2α siRNA completely suppressed the hypoxia-dependent increase of the targeted protein, but did not affect the expression of the other HIF-α isoform. The presence both HIF siRNAs completely inhibited the expression of both proteins. It is of note that in each of 4 independent experiments, under hypoxic conditions the presence of HIF siRNAs suppressed HIF protein expression to a level equal to that noted under normoxic conditions. The specificity of this system was also demonstrated by the finding that treatment with non-targeting and cyclophilin siRNA, as well as mock transfection, did not affect expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α. In addition, cyclophilin B expression was suppressed by the presence of cyclophilin B siRNA, but was unaffected by treatment with HIF siRNAs (bottom blot).

Role of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxia-dependent effects on PAI-1 expression

HTR-8/SVneo cells were incubated for 48 h under normoxic, hypoxic, and hypoxic conditions with siRNAs as described above, and levels of PAI-1 in culture media were determined by ELISA. We observed that compared to hypoxic treatment alone the presence of HIF-1α or HIF-2α siRNA suppressed PAI-1 levels 31% and 35% respectively, although these effects did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5). Treatment with both siRNAs significantly suppressed PAI-1 levels 50% (P<0.02, denoted by * in Fig. 5). It is of note that the presence of non-targeting RNA significantly increased PAI-1 levels 48% (P<0.01). Although mock transfection enhanced PAI-1 levels 32%, this effect was not statistically significant. Statistically significant suppression of PAI-1 levels by HIF-1α, HIF-2α and combined siRNA treatments was noted when compared to non-targeting and mock treatment groups (P<0.001 for all twoway comparisons, denoted by +). The presence of cyclophilin B siRNA did not affect PAI-1 levels, and as a result only the combined presence of HIF-1α or HIF-2α siRNAs significantly reduced PAI-1 levels compared to the cyclophilin B siRNA treatment group (P<0.03).

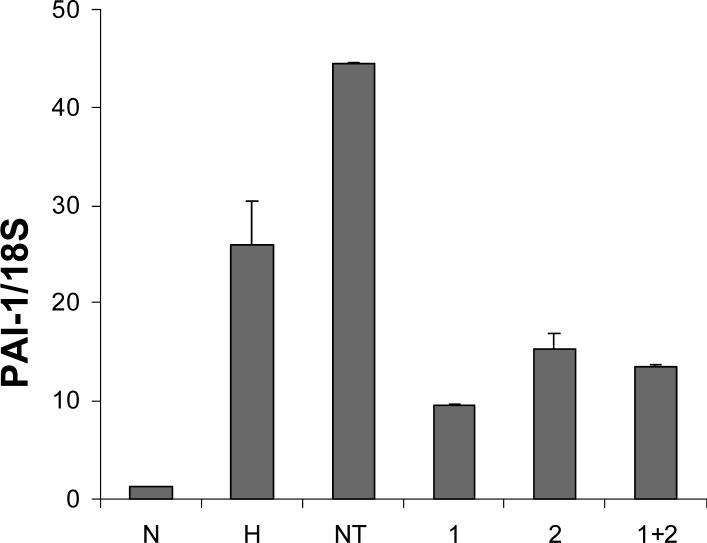

We then examined the effects of treatment with HIF siRNAs on hypoxia-dependent modulation of PAI-1 mRNA expression. For this experiment, cells were maintained for 48 h under normoxic conditions, hypoxia alone, or hypoxia in the presence of siRNA specific for HIF-1α , HIF-2α , both HIF-1α and HIF-2α, or non-targeting sequence. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed to quantify mRNA levels of PAI-1 and results were normalized to that of 18S RNA. As shown in Fig. 6, hypoxic treatment induced PAI-1 mRNA expression approximately 20-fold compared to normoxic control. Treatment of cells with HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or both siRNAs reduced the hypoxia-dependent increase in levels of PAI-1 mRNA 63, 42, and 48%, respectively. This suggests that the presence of HIF-1α and HIF-2α siRNA suppress the level of PAI-1 protein by reducing the expression of PAI-1 mRNA.

Figure 6.

Effect of HIF siRNAs on PAI-1 mRNA levels in HTR-8/SVneo cells.

Cells were incubated for 48 h under normoxic (N) or hypoxic (H) conditions alone, or under hypoxia with non targeting (NT), HIF-1α (1), HIF-2α (2), or HIF-1α and HIF-2α (1+2) siRNAs. Levels of PAI-1 mRNA were determined by quantitative real-time PCR and were normalized to that of 18S RNA. Results are expressed as a mean + SE from duplicate determinations in a single experiment representing 3 identically conducted ones.

DISCUSSION

We initially demonstrated using HTR-8/SVneo cells that levels of PAI-1 released to culture media far exceeded that of PAI-2. This is not unexpected as PAI-1 expression in normal placenta throughout gestation is localized to extravillous trophoblast [9], the cell-type from which the HTR-8/SVneo cell line is derived [30]. Conversely, PAI-2 was primary localized to the syncytial layer of villous trophoblast across gestation [9,14-16]. We noted that hypoxic treatment markedly enhanced the synthesis of PAI-1 in both serum-containing and serum-free culture media. Conversely, PAI-2 levels were not significantly affected by hypoxic treatment. Cells were maintained at an oxygen concentration of 1−3% oxygen, a level similar to that which the placenta is exposed to before 10 weeks of pregnancy [32]. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating hypoxic induction of PAI-1 expression in trophoblasts and other cell types, and the demonstration of a HRE in the PAI-1 promoter [21-23]. We observed that hypoxic treatment induced a small (∼40%) but significant increase in PAI-1 levels in culture media from BeWo choriocarcinoma cells, whereas PAI-1 levels were extremely low in JAR choriocarcinoma cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (not shown). This indicated that the HTR-8/SVneo cell line is well suited for studies of hypoxic regulation of trophoblast PAI-1 expression.

Our results also demonstrated that enhancement of HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels by hypoxic treatment preceded stimulation of PAI-1 levels. Levels of PAI-1 in culture medium increased slightly between 24 and 48 h of hypoxic treatment, whereas HIF expression was markedly suppressed following prolonged hypoxic treatment (compare Figs. 1A and 3). These disparate time courses of hypoxic induction may reflect the time required for HIF to enhance PAI-1 transcription, and for translation and secretion of PAI-1 to then occur. It is also likely that secreted PAI-1 protein is more stable than intracellular HIF leading to elevated PAI-1 expression long after HIF levels have decreased. Other groups have noted a marked decrease in HIF protein levels, especially that of HIF-1α, under prolonged hypoxic treatment [37,38]. This decrease was attributed to a reduction in HIF mRNA stability and an increase in the levels of an endogenous antisense HIF-1α transcript [37,38].

We then used siRNA technology to dissect the roles of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in the regulation PAI-1 expression. Western blotting initially revealed that treatment with the three targeting siRNAs (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and cyclophilin B) resulted in almost a complete suppression of the corresponding proteins, indicating an efficacious uptake and action of siRNA. We are unaware of any report in which siRNA has been effective in modulation of gene expression in primary cultures of trophoblasts. It our experience that primary cultures of cytotrophoblasts are exceedingly difficult to transfect with nucleic acids. Thus, although use of a trophoblast cell line may reduce the ability to extrapolate results to in vivo conditions, it greatly facilitates molecular manipulations that are at best extremely difficult to perform in primary cultures.

With the efficacy of HIF siRNA treatment established, we then examined the effect of HIF suppression on the stimulation of PAI-1 levels under hypoxic conditions. We observed that the hypoxia-mediated increase in PAI-1 levels in culture media was similarly reduced approximately 33% by treatment with either HIF-1α or HIF-2α siRNA alone, with the combined treatment significantly suppressing PAI-1 levels approximately 50%. It is of note that the presence of non-targeting siRNA or transfection reagents alone (mock condition) increased PAI-1 levels under hypoxic conditions, whereas the presence of cyclophilin B siRNA did not affect PAI-1 levels. The importance of using multiple controls in siRNA studies has been previously described [29]. Of note, we observed that a second non-targeting siRNA did not affect PAI-1 levels under normoxic conditions, and actually suppressed PAI-1 levels approximately 20% under hypoxic conditions (not shown). This indicates that regulation of PAI-1 expression by non-targeting siRNAs is sequence specific. It has been observed that interleukins and interferons are non-specifically induced by siRNA treatment, suggesting that siRNA stimulates innate cytokine immune responses [39]. Since PAI-1 levels are stimulated by cytokines including IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α [40], this suggests that non-specific modulation of PAI-1 levels by siRNAs and/or transfection reagents may be due to effects on cytokine levels in HTR-8/SVneo cells. Our observation that the presence of HIF-1α and HIF-2α siRNAs reduced PAI-1 mRNA levels under hypoxic conditions as quantitated by real-time PCR, indicated that HIF modulates PAI-1 expression at a transcriptional level.

Our results indicate that HIF-1α and HIF-2α play similar roles in the hypoxia-mediated increase in PAI-1 expression in HTR-8/SVneo cells. Several studies suggest that relative contributions of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxia-mediated changes in gene expression are both cell type- and gene-specific [26-28,41]. Using siRNAs it was demonstrated that a panel of hypoxia-responsive genes were dependent on both HIF-1α and HIF-2α in HUVECs and MDA 468 breast cancer cells, but only on HIF-2α in 786−0 renal carcinoma cells [26]. Another study showed HIF-α isoform specific transcriptional activation for several genes in renal carcinoma cells, indicating that they have contrasting properties in the biology of renal cell carcinoma [28]. The only report addressing the role of HIFs in PAI-1 regulation was one using MCF7 breast cancer cells in which siRNA treatment revealed a dependence on both HIF-1α and HIF-2α for hypoxia-dependent changes in PAI-1 mRNA expression [41]. In contrast to our observations, the effect of HIF-2α siRNA on PAI-1 expression was greater than that noted for HIF-1α siRNA. In addition, the results from the present study indicate a critical role for HIF-1α and HIF-2α in hypoxic regulation of secreted PAI-1, the active form of this protein.

Studies suggest that HIF plays a role in the regulation of trophoblast function. It was shown that HIF-1α and HIF-2α are expressed by villous cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblast, as well as extravillous cytotrophoblasts, and their expression in placenta decreases with gestational age [42,43]. It was suggested that the gestational age dependent reduction in HIFs likely reflects their degradation in response to increasing oxygen concentration [42,43]. In support of this premise is the finding of increased placental expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in pregnancies complicated by PE [44], which are also characterized by placental hypoxia [1,3,45].

In conclusion, our results indicate that both HIF-1α and HIF-2α play an important role in hypoxia-dependent regulation of PAI-1 levels in a trophoblast cell model, a finding of particular significance during the first trimester of pregnancy when cytotrophoblasts may be exposed to low concentrations of oxygen [32]. Our results may also be important in furthering our understanding of placental dysfunction in pregnancies complicated by PE which is associated with prolonged placental hypoxia and elevated levels of placental PAI-1.

Acknowledgments

*These studies were supported in part through NIH grant HD 33909 (S.G.) and NIH Training Grant HL07649 (E.S.M.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaufmann P, Black S, Huppertz B. Endovascular trophoblast invasion: implications for the pathogenesis of intrauterine growth retardation and preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.014977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sood R, Kalloway S, Mast AE, Hillard CJ, Weiler H. Fetomaternal cross talk in the placental vascular bed: control of coagulation by trophoblast cells. Blood. 2006;107:3173–3180. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zini JM, Murray SC, Graham CH, Lala PK, Kariko K, Barnathan ES, Mazar A, Henkin J, Cines DB, McCrae KR. Characterization of urokinase receptor expression by human placental trophoblasts. Blood. 1992;79:2917–2929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Latest advances in understanding preeclampsia. Science. 2005;308:1592–1594. doi: 10.1126/science.1111726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vassalli JD, Sappino AP, Belin D. The plasminogen activator/plasmin system. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1067–1072. doi: 10.1172/JCI115405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loskutoff DJ, Sawdey M, Keeton M, Schneiderman J. Regulation of PAI-1 gene expression in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprengers ED, Kluft C. Plasminogen activator inhibitors. Blood. 1987;69:381–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pannekoek H, Veerman H, Lambers H, Diergaarde P, Verweij CL, van Zonneveld AJ, van Mourik JA. Endothelial plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI): a new member of the Serpin gene family. EMBO J. 1986;5:2539–2544. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feinberg RF, Kao LC, Haimowitz JE, Queenan JT, Jr, Wun TC, Strauss JF, III, Kliman HJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor types 1 and 2 in human trophoblasts. PAI-1 is an immunocytochemical marker of invading trophoblasts. Lab Invest. 1989;61:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann GE, Glatstein I, Schatz F, Heller D, Deligdisch L. Immunohistochemical localization of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and the plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2 in early human implantation sites. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:671–676. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schatz F, Lockwood CJ. Progestin regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in primary cultures of endometrial stromal and decidual cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:621–625. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.3.8370684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radtke KP, Wenz KH, Heimburger N. Isolation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-2 (PAI-2) from human placenta. Evidence for vitronectin/PAI-2 complexes in human placenta extract. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1990;371:1119–1127. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1990.371.2.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Heijne G, Liljestrom P, Mikus P, Andersson H, Ny T. The efficiency of the uncleaved secretion signal in the plasminogen activator inhibitor type 2 protein can be enhanced by point mutations that increase its hydrophobicity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15240–15243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estelles A, Gilabert J, Keeton M, Eguchi Y, Aznar J, Grancha S, Espna F, Loskutoff DJ, Schleef RR. Altered expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 in placentas from pregnant women with preeclampsia and/or intrauterine fetal growth retardation. Blood. 1994;84:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estelles A, Gilabert J, Grancha S, Yamamoto K, Thinnes T, Espana F, Aznar J, Loskutoff DJ. Abnormal expression of type 1 plasminogen activator inhibitor and tissue factor in severe preeclampsia. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:500–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grancha S, Estelles A, Gilabert J, Chirivella M, Espana F, Aznar J. Decreased expression of PAI-2 mRNA and protein in pregnancies complicated with intrauterine fetal growth retardation. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salafia CM, Minior VK, Pezzullo JC, Popek EJ, Rosenkrantz TS, Vintzileos AM. Intrauterine growth restriction in infants of less than thirty-two weeks' gestation: associated placental pathologic features. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salafia CM, Pezzullo JC, Minior VK, Divon MY. Placental pathology of absent and reversed end-diastolic flow in growth-restricted fetuses. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:830–836. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer S, Pollheimer J, Hartmann J, Husslein P, Aplin JD, Knofler M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits trophoblast migration through elevation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in first-trimester villous explant cultures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:812–822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber AV, Saleh L, Bauer S, Husslein P, Knofler M. TNFalpha-mediated induction of PAI-1 restricts invasion of HTR-8/SVneo trophoblast cells. Placenta. 2006;27:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchiyama T, Kurabayashi M, Ohyama Y, Utsugi T, Akuzawa N, Sato M, Tomono S, Kawazu S, Nagai R. Hypoxia induces transcription of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene through genistein-sensitive tyrosine kinase pathways in vascular endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1155–1161. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fitzpatrick TE, Graham CH. Stimulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in immortalized human trophoblast cells cultured under low levels of oxygen. Exp Cell Res. 1998;245:155–162. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kietzmann T, Roth U, Jungermann K. Induction of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression by mild hypoxia via a hypoxia response element binding the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in rat hepatocytes. Blood. 1999;94:4177–4185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell PH. Hypoxia-inducible factor as a physiological regulator. Exp Physiol. 2005:791–797. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.030924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haase VH. The VHL/HIF oxygen-sensing pathways and its relevance to kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1302–1307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sowter HM, Raval RR, Moore JW, Ratcliffe PJ, Harris AL. Predominant role of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor (HIF)-1alpha versus HIF-2alpha in regulation of the transcriptional response to hypoxia. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6130–6134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang V, Davis DA, Haque M, Huang LE, Yarchoan R. Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in HEK293T cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3299–32306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schutze N. siRNA technology. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;213:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham CH, Hawley TS, Hawley RG, MacDougall JR, Kerbel RS, Khoo N, Lala PK. Establishment and characterization of first trimester human trophoblast cells with extended lifespan. Exp Cell Res. 1993;206:204–211. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y, Ryu JS, Dulay A, Segal M, Guller S. Regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 expression in a human trophoblast cell line by glucocorticoid (GC) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta. Placenta. 2002;23:727–34. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(02)90863-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress. A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:2111–2122. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee MJ, Ma Y, LaChapelle L, Kadner SS, Guller S. Glucocorticoid enhances transforming growth factor-beta effects on extracellular matrix protein expression in human placental mesenchymal cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1246–1252. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krikun G, Mor G, Alvero A, Guller S, Schatz F, Sapi E, Rahman M, Caze R, Qumsiyeh M, Lockwood CJ. A novel immortalized human endometrial stromal cell line with normal progestational response. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2291–2296. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lala PK, Graham CG. TGF-beta-responsive human trophoblast-derived cell lines. Placenta. 2001;22:889–890. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang GL, Semenza GL. Purification and characterization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1230–1237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li QF, Wang XR, Yang YW, Lin H. Hypoxia upregulates hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-3alpha expression in lung epithelial cells: characterization and comparison with HIF-1alpha. Cell Res. 2006;16:548–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchida T, Rossignol F, Matthay MA, Mounier R, Couette S, Clottes E, Clerici C. Prolonged hypoxia differentially regulates hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha expression in lung epithelial cells: implication of natural antisense HIF-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14871–14878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pauls E, Senserrich J, Bofill M, Clotet B, Este JA. Induction of interleukins IL-6 and IL-8 by siRNA. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;147:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Healy AM, Gelehrter TD. Induction of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in HepG2 human hepatoma cells by mediators of the acute phase response. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19095–19100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elvidge GP, Glenny L, Appelhoff RJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Ragoussis J, Gleadle JM. Concordant regulation of gene expression by hypoxia and 2-oxoglutarate dependent dioxygenase inhibition; the role of HIF-1alpha , HIF-2alpha and other pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15215–15226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajakumar A, Conrad KP. Expression, ontogeny, and regulation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors in the human placenta. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:559–569. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.2.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ietta F, Wu Y, Winter J, Xu J, Wang J, Post M, Caniggia I. Dynamic HIF-1alpha regulation during placental development. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:112–121. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.051557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajakumar A, Whitelock KA, Weissfeld LA, Daftary AR, Markovic N, Conrad KP. Overexpression of the hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, HIF-1alpha and −2 alpha, in placentas from women with preeclampsia. Biol Reprod. 2001;64:499–506. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/64.2.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soleymanlou N, Jurisica I, Nevo O, Ietta F, Zhang X, Zamudio S, Post M, Caniggia I. Molecular evidence of placental hypoxia in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4299–4308. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]