Deliberate self-poisoning has become an increasingly common response to emotional distress in young adults,1 and it is now one of the most frequent reasons for emergency hospital admission.2 In industrialised countries, the drugs people commonly take in overdose - analgesics, tranquillisers, antidepressants3- are relatively non-toxic. The estimated case fatality for overdose in England, for example, is around 0.5%.4 Most individuals who self-harm do not intend to die. Studies carried out in industrialised countries have found that only 2% go on to commit suicide in the subsequent 12 months.5

In developing countries the situation is quite different.6 The substances most commonly used for self-poisoning are agricultural pesticides.6,7,8,9,10,11 Overall case fatality ranges from 10% - 20%.12 For this reason, deaths from pesticide poisoning make a major contribution to patterns of suicide in developing nations, particularly in rural areas.6 In rural China, for example, pesticides account for over 60% of suicides.8 Similarly high proportions of suicides are due to pesticides in rural areas of Sri Lanka (71%),13 Trinidad (68%),14 and Malaysia (>90%).10 There is, however, no evidence that levels of suicidal intent associated with pesticide ingestion in these countries are any higher than those associated with drug overdose in industrialised countries, where the drugs taken in overdose are less toxic.

Patterns of suicide in countries where pesticide poisoning is commonplace

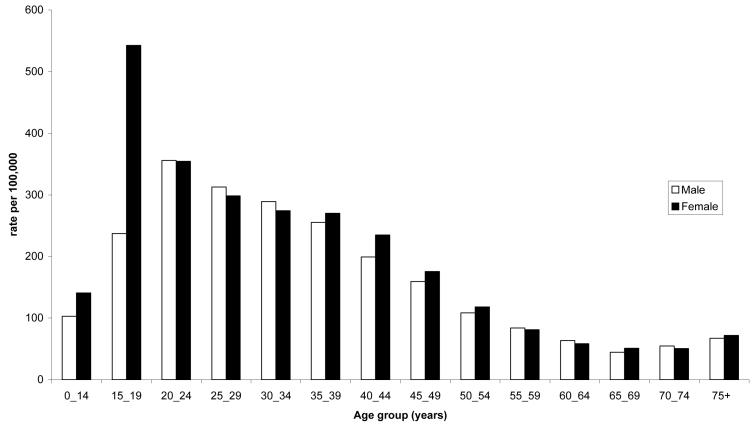

In countries where the use of pesticides for self-harm is commonplace conventional epidemiological features of suicide may be distorted. In industrialised nations, suicide rates are two to three times higher in men than women, and its incidence tends to increase with age, although in some countries recent rises in young male suicides have distorted this pattern.15 The incidence of non-fatal self-harm in industrialised countries is 20+ times higher than that of suicide; in contrast to suicide, self-harm rates peak in the 15-24 year olds and are generally highest in women (see fig. 1a).16

Fig 1.

Fig 1a Hospital admissions for self poisoning: England (source: Hospital Episode Statistics April 1999-March 2000)

Fig 1b Hospital admissions for self-poisoning: Sri Lanka (data are for the two secondary referral hospitals in North Central Province: April 2002 - March 2003)

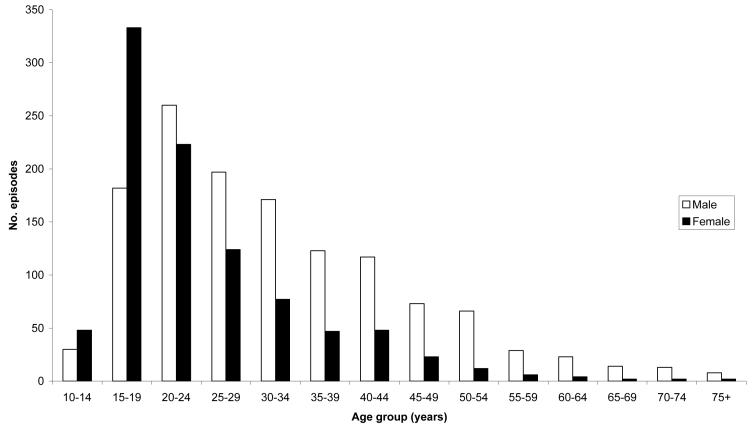

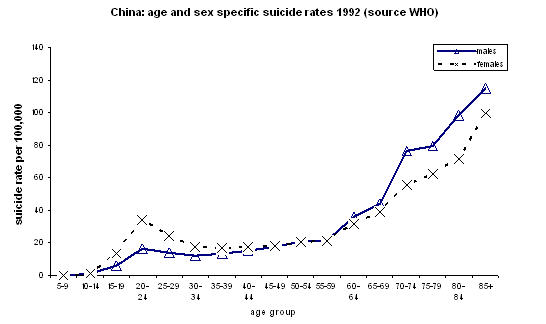

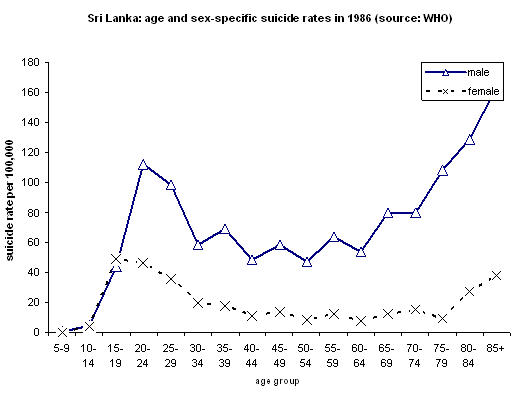

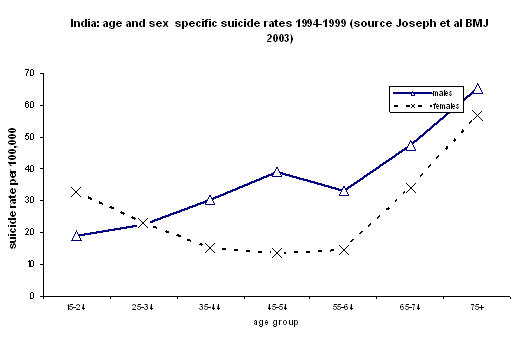

A possible explanation for these differences in the age- and sex- patterning of fatal and non-fatal self-harm is that young people, particularly females, are more likely to engage in impulsive acts of self-harm – as indicated by the comparatively lower levels of suicidal intent in young people.17 Because these acts are unplanned, the methods used are those that are readily available at the time of acute distress - prescribed and non-prescribed medicines – and these are relatively non-toxic. If more lethal methods of self-harm, such as pesticides, were favoured and readily accessible in industrialised nations the epidemiology of suicide in these countries might be quite different. Thus the widespread availability of pesticides may contribute to the difference in the age- and sex- patterning of suicide in China,18 Sri Lanka,19 India,20 and several other developing countries compared with that commonly seen in industrialised nations (fig. 2). In these developing countries some of the highest rates are seen in young adults and the ratio of male: female suicide approaches or exceeds unity at this age.

Fig 2.

Age and sex patterns of suicide. a. In China (Source: WHO), b. Sri Lanka (Source: WHO), and c. Kaniyambadi region, S. India (Source: Joseph et al.20)

In China, whilst suicide rates do tend to increase with age, there is a notable peak in rates amongst males and females aged 20-25 (fig. 2); recent data show that this peak is more prominent in rural localities.18 In rural India rates of suicide in 15-24 year old females are higher than rates in males of the same age and most other female age groups.20 Similar patterns are seen in Sri Lanka (fig. 2). In both China and Sri Lanka pesticides are the most frequently used method of suicide, likewise in India self-poisoning is the commonest method 20 and pesticides are the most frequently used agents.9,21 It is of note that the age- and sex- patterns of self-poisoning in Sri Lanka in the younger age groups are similar to those in industrialised countries (fig. 1b) although, in contrast, the case fatality in Sri Lanka is much higher (fig 2c and 2d).

Part of the distinct age- and gender-patterns of suicide deaths in the developing world may therefore reflect a mixture of deaths with high suicidal intent (predominantly in the elderly) and an excess of deaths with low suicidal intent amongst the young where the method chosen for impulsive acts of self-harm (pesticide ingestion) is highly lethal. A possibility strikingly born out in Western Samoa in the 1980s, where two thirds of all suicides were a result of pesticide ingestion and the age- and sex-patterning of suicide and non-fatal self harm were almost identical.22

Method availability and suicide

The common use of pesticides for self-harm in part reflects their ease of availability. Whilst their use in agriculture is widespread in industrialised countries, large scale farming is practiced by a small number of landowners thus reducing the number of people with direct access to pesticides. In contrast, most people living in rural regions of developing countries are involved in agriculture and farm small areas of land. Subsistence farmers keep their own supply of pesticides, commonly within, or close to, the household.23 A recent study in China found that 65% of pesticide suicides used chemicals stored in the home.8

There is general consensus that the ease of availability of particularly lethal means of self-harm may influence patterns of suicide. Suicidal impulses are often short lived and if time can be ‘bought’ allowing such impulses to pass - by making the means of suicide less readily available – a proportion of suicides will be prevented.24 The best documented evidence of this was the effect of the detoxification of the domestic gas supply in Britain in the 1960s25 – this was thought to have contributed to the prevention of an estimated 6,700 suicides.26 Similarly, temporal and geographical variations in the availability of other commonly used methods have influenced patterns of suicide in Australia (barbiturates),27 USA (firearms),28,29 and Britain (catalytic converters for car exhaust fumes).30

This evidence has prompted the inclusion of policies aimed at reducing access to, or the lethality of, commonly used methods within national and international suicide prevention strategies.31,32,33 In Britain attention has focussed on restricting the availability of paracetamol (acetaminophen)34,35 and in the USA there are similar concerns about the ease of availability of firearms.28,29

The number of deaths caused by pesticides36 make Western concerns about these two methods of suicide appear somewhat trivial. For example, in Britain where paracetamol suicide is comparatively common,34 there are only around 200 paracetamol suicides per year (<4% of all suicides).35 If a similar proportion of suicides were due to paracetamol worldwide (an overestimate34) then using the WHO's current estimate of 849,000 suicides worldwide each year37 a maximum of 34,000 of these might be attributable to paracetamol.

In contrast, the WHO estimated in 1990 that there are around 3 million hospital admissions for pesticide poisoning each year, 2 million of which are as a result of deliberate ingestion, and these result in around 220,000 deaths.36 The size of the problem is probably larger now – there have, for example, been well-recognised increases in pesticide poisonings in South Asia.21

The best evidence for estimating the global burden of suicide deaths from pesticide ingestion comes from China and South East Asia. In 2001 there were an estimated 517,000 suicides in developing countries in these regions37 and research evidence (see above) suggests pesticide ingestion accounts for over 60% of these suicides. We therefore estimate there are around 300,000 pesticide suicides each year in these regions alone. As pesticide suicides from other developing nations in Africa and South America are not included in this figure the global toll is likely to be higher.

Economics of pesticide poisoning

Deaths from pesticide ingestion are a major contributor to the global burden of suicide and premature mortality. This burden is increased by the economic and indirect health care effects of self-harm following ingestion of pesticides. Such effects have been less well documented in the research literature.

The hospital management of pesticide poisoning often requires intensive care, in particular ventilation. In 1995-6, in one general hospital in Sri Lanka, 41% of bed occupancy on medical intensive care beds was for the treatment of pesticide poisoning.38 This not only drains limited healthcare budgets but also prevents the treatment of other patients requiring intensive care. Furthermore, the loss through premature death, of young, economically active, community members and the impact of their death on others (spouses, children, friends and family) may influence productivity in communities that are on the margins of subsistence.

The costs of self-harm should be balanced against agricultural benefits of pesticides. These have not been formally quantified and work over the last 20 years with integrated pest management have shown that reduced use of pesticides can be compatible with at least stable levels of crop production.39,40 Pesticides are also used to control disease vectors (e.g. mosquito vectors of dengue and malaria) but supplies of pesticides used for this purpose are kept in official store rooms and are therefore less likely to be available for acts of self-harm.

Any analysis of the competing adverse and beneficial effects of pesticides should incorporate the possibility of replacing pesticides which are toxic to humans with less toxic, but equally effective alternatives.6 Likewise the short term effects on crop yields should be balanced against wider effects on the environment, development of parasite resistance, and possible longer term effects of pesticide exposure on human health.6

How can the death toll from pesticide poisoning be reduced?

Possible approaches to reducing deaths from pesticide ingestion are outlined in the Table. The importance of broad based commitment from industry as well as national and international health and regulatory organisations is highlighted.

Table.

Possible approaches to reducing deaths from intentional pesticide ingestion

| Possible strategy | Advantages | Disadvantages | Who should be responsible for action? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce availability of highly toxic pesticides | |||

| Introduce a ‘minimum pesticides list’ 6 restricting pesticide use to a few, less dangerous pesticides. | Reduced case fatality. | Industry pressure against restriction from companies whose products are regulated. | WHO/FAO National regulatory authorities / National Government |

| Prohibit sales of the pesticides most lethal to humans after ingestion. | Reduced case fatality. | Replacement pesticides may be less effective agriculturally. | National Government |

| Subsidise or reduce the costs of pesticides which are less toxic to humans | Reduced case fatality. | Reduced industry profits Costs to national Governments May increase pesticide use |

Industry National Government |

| Ensure all pesticides are kept in a locked cabinet with the key held by the licensed user. | Limited availability in times of acute emotional crisis. | Inconvenience. Costs, difficulty policing legislation. |

National Government (legislation) Purchaser of pesticide |

| Appoint a village elder, schoolteacher, police officer or councillor to hold the locality's stocks of pesticides centrally. | Limited availability at times of emotional crisis. | Inconvenience. Administration costs. Diminished access for farmers. |

National Government (legislation) Local Government / community |

| Reduce the use of pesticides in agricultural practice (e.g. Integrated Pest Management (IPM))39. | Less pesticides around at times of emotional crisis. | Reduced industry profit Possibly reduced agricultural yield – further studies are required. |

United Nations National Government |

| Ensure all remaining pesticides are returned to vendor after application. | Limited availability in times of emotional crisis. | Administration costs. Costs to farmers. |

Local Government / community |

| Reduce use of pesticides in acts of self harm | |||

| Public education campaigns regarding the dangers of pesticide ingestion.22 44 | May lead to reduced quantities of pesticides being taken in self harm. May lead to more rapid help seeking from those who have ingested pesticides, as well as their friends and relatives. |

May, by highlighting lethal dose and potential for using this method, lead to increases in suicides. There is already widespread awareness regarding the dangers / toxicity of pesticides. No clear evidence of effect in W Samoa.22 |

National and Local Government |

| Better labelling of products with advice regarding dangers, need for safe-keeping, need for early treatment. | Limited availability. Reduced case fatality because of early help-seeking and treatment |

Industry. National and Local Government. |

|

| Reduce the toxicity of pesticides taken in overdose | |||

| Addition of emetic agent / antidote to all pesticide products. | Possibly reduced case fatality. | Costs to industry. Possibly reduced agricultural effectiveness of the pesticide. No consistent evidence of effectiveness.44 |

Industry. National regulatory bodies. |

| Change formulation of pesticides: reduced concentration or addition of agents that make them unpleasant to taste / smell. | Reduced case fatality. | Costs to industry. | Industry |

| Industry research to produce agents which are non-toxic to humans | Reduced case fatality. | Costs to industry. | Industry |

| Improved management of pesticide poisoning | |||

| Ensure all villages have first aid kits for the immediate management of pesticide poisoning – charcoal; possibly emetics | Possibly reduced poison absorption and therefore case fatality. | Costs of ensuring supplies regularly updated. No evidence of effectiveness |

National and Local Government |

| Improve speed of transfer to hospital. | Ensure patient is in a hospital when deterioration occurs. | Costs to cash restricted health services. | National and Local Government |

| Ensure all hospitals have adequate supplies of antidotes. | Reduce requirements for transfer, reduce case fatality. | Costs to cash restricted health services. | National and Local Government |

| Perform research to establish best management guidelines and determine effectiveness of antidotes. | Establishment of agreed best practice. | Major research funding bodies. | |

| Promulgate management guidelines. | Reduced case fatality | Costs of synthesising evidence to produce such guidelines | Major research funding bodies. |

The first broad approach is to restrict the availability of pesticides either directly, for example through restricting the import and use of pesticides, or indirectly through ensuring supplies are kept in a secure facility in each geographic locality. Restricting availability could be achieved by either direct control of particular pesticides (banning, requiring licences for use or prescriptions) or through the promotion of practices that minimise their use. Such health protection approaches appear to have led to a reduction in serious paracetamol poisonings in England35 and a decline in barbiturate suicides in Australia.27 The World Health Organisation (WHO) has encouraged countries to restrict the availability of more lethal pesticides 32 and countries such as Sri Lanka have followed this approach.41 In Jordan, a steady rise in fatal pesticide poisonings was reversed by increased awareness of the problem, decreased imports of some toxic pesticides and bans on the imports of others.42 Similar effects have been observed in Western Samoa after reduced use of paraquat and a campaign to raise awareness of suicide, here fluctuations in imports were driven by the nation's financial problems rather than a concern with suicide.22

The second approach is to improve public education regarding the dangers of pesticide poisoning and the safekeeping of pesticides – through media campaigns and clear labelling of product containers. The effects are difficult to predict and there is a suggestion that enhanced knowledge concerning the toxicity of pesticides resulted in an increase in their use for self-harm in some settings.12 Furthermore, it is widely recognised that media portrayal of acts of self-harm can lead to increases in ‘copy-cat’ suicides.43

The third general approach is to encourage manufacturers to improve the safety of their products. This may be achieved by diluting the concentrations of liquid pesticides, incorporating emetics or agents to make them unpleasant to taste or, more fundamentally, to produce pesticides which are non-toxic to humans.44 Company responsibility for the safe use of pesticides should extend for the entire life cycle of their use.

Lastly, if the occurrence and lethality of pesticide ingestions cannot be prevented then improved medical management is crucial.12 The lethality of pesticide poisoning is for the most part due to the difficulty of treatment and their greater toxicity compared to substances taken in overdose in industrialised countries. Antidotes to pesticides are not completely effective. In rural areas, where the majority of cases occur, health care is often distant and of poor ‘quality’. In the UK, where paracetamol is the most common poison used for self-harm, a similar situation could be envisaged if all the antidotes became unavailable – the medical wards might once again become filled with paracetamol poisoned patients with either anticipated or florid liver failure.

Why has there been a failure to act?

The problem of death from pesticide self-poisoning is neither new12,45,46,47,48nor unique to a few countries, so reasons for the lack of a global response need to be understood if this continuing tragedy is to be reversed.

Five main factors appear to contribute. First, the pattern of agriculture practised in developing countries – where most people living in rural areas cultivate small areas of land – is quite different from that in industrialised nations where a small number of farmers cultivate large tracts of land. In industrialised countries access to pesticides is therefore largely restricted to the few individuals engaged in farming. In developing nations pesticides are available within most peoples' place of residence. Interventions to limit access in such settings are complex and need to involve most rural adults, rather than a select few.

Second, the sale of pesticides is a multi-million dollar business. 1.5 million tons of pesticides are sold annually and sales are worth an estimated US$ 30 billion.6 Tensions commonly exist between commercial interests and population health and industry has not always acknowledged the impact of the easy availability of lethal suicide methods on patterns of suicide.49 In describing Western Samoa's preventive considerations following the epidemic rise in pesticide suicides in that country Bowles noted: “There was at that time a contentious debate about actually banning paraquat entirely. We knew however that there were powerful and influential people who had a vested interest in continuing the importation and we did not want to be aligned with a lobby group likely to fail.”22

Third, the issue of pesticide self-poisoning has never been taken up as a campaign issue by any of the international organizations. The World Health Organization (WHO) is the pre-eminent public health organization and its Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence (MNH) is responsible for suicide prevention.50 It has managed to successfully draw mental health up the worldwide political agenda over the last 10 years.32 It has also emphasised the global health importance of suicide, organising workshops across the world to discuss strategies for reducing self-harm, but it has not taken up pesticides as a central issue. Recent WHO publications with major input from the MNH,32,51, have put greater emphasis on psychiatric and social models of self-harm aetiology. While pesticide self-poisoning was mentioned in both reports, it received much les attention than its importance warrants.

The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) is the major WHO program dealing with pesticides.52 It was set up in 1980 by the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization, and the WHO, to establish the scientific basis for safe use of chemicals and to strengthen national capabilities for chemical safety. Current IPCS activities aim to increase knowledge of the epidemiology of pesticide poisoning and to encourage the setting up of poisoning information centres.52,53 The IPCS has not, however, actively taken up the issue of intentional pesticide self-poisoning, concentrating instead on occupational and environmental poisoning.54 This is unfortunate since its own studies have indicated the great importance of self-poisoning in the Asia Pacific region.53 The interests of its parent organisations may be the reason for this lack of advocacy for the problem of intentional poisoning.

Fourth, the self-inflicted nature of suicide, together with the fact there are fewer suicide deaths than deaths from other global health problems such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, may have lead to policy makers giving it lower priority than the number of premature deaths warrant.

Fifth, pesticide self-poisoning is ideologically and politically inconvenient. Pesticide use has adverse effects on the environment and human health.55,56,57 This has become a major global political issue. Much of the adverse effects of pesticides are considered to result from their overuse and poor treatment of workers and communities due to globalisation58 – of which pesticide corporations are major participants. The issue has been taken up by numerous national and international NGOs, in continual ‘battle’ with the pesticide companies. In this battle, the fact that the vast majority of severe and fatal pesticide cases are self-inflicted is inconvenient to the environmentalists. If the pesticide industry can argue that they should not be held responsible for people who drink pesticides, then this may be seen as undermining the environmentalists' case. People therefore want to avoid the issue of self-poisoning and deal with issues where the pesticide industry, and globalisation in general, can be held responsible.

This need not be true. An overall assessment of public health, environmental and agricultural factors should determine regulatory actions, not simply their political appropriateness. Pesticide self-harm is just as important as occupational poisoning for regulatory issues. And in some countries, regulatory authorities have been very effective in banning pesticides that have been problems only for self-harm.41

Conclusion

Pesticide self-poisoning is a major contributor to population patterns of morbidity and mortality in developing nations. The use of pesticides for self-poisoning may distort conventional epidemiological features of suicide in these countries and contribute to their excess premature mortality. We estimate there are around 300,000 self-inflicted pesticide deaths worldwide each year. Research dating back over 30 years has documented the size of this problem and yet contemporary research bears witness to its continuing impact.

Research to identify the most acceptable means of restricting the availability of pesticides within rural communities is urgently required together with randomised controlled trials to determine the best means of treatment and cost-effectiveness of possible interventions. Some of this research is now underway (M Eddleston, unpublished). Preventive measures must take account of the local needs and context and should be rigorously evaluated.

Thus far there has been no global leadership to respond to the problem. Engagement of national government and WHO in the issue is essential. Commitment from industry and the need for them to acknowledge their responsibility for some of these deaths is vital (Table) as is the need to ensure they understand the scale, importance and preventability of the problem. Reducing the number of pesticide deaths by 50% could rapidly reduce the number of suicides worldwide by 150,000. This is quite possible.

Acknowledgements

We thanks Shah Ebrahim, John Haines, Flemming Konradsen and Mark van Ommeren for helpful comments and suggestions and Nicos Middleton, Davidson Ho and Sanjay Kinra for obtaining some of the suicide statistics. Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data were made available by the Department of Health to the authors courtesy of the HES National Service Framework project (Prof. Shah Ebrahim and colleagues), funded by a South and West Regional project R&D grant. The MRC HSRC are data custodians and also fund some of the support costs. The Department of Social Medicine is the lead Centre of the MRC Health Services Research Collaboration. ME is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow in Tropical Clinical Pharmacology, funded by grant GR063560MA.

Reference List

- 1.NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Deliberate self-harm. Effective Healthcare Bulletin. 1998;4:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnell DJ, Brooks J, Peters TJ. Epidemiology and patterns of hospital use after parasuicide in the south west of England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1996;50:24–29. doi: 10.1136/jech.50.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michel K, Ballinari P, Bille-Brahe U, et al. Methods used for parasuicide: results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35:156–163. doi: 10.1007/s001270050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunnell D, Ho DD, Murray V. Medical Management of Deliberate Drug Overdose - a Neglected area for Suicide Prevention? Emergency Med J. 2003 doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.000935. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. Systematic review. Br.J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eddleston M, Karalliedde L, Buckley N, et al. Pesticide poisoning in the developing world--a minimum pesticides list. Lancet. 2002;360:1163–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latha KS, Bhat SM, D'Souza P. Suicide attempters in a general hospital unit in India: their socio-demographic and clinical profile - emphasis on cross-cultural aspects. Acta Paediatrica Scand. 1996;94:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002;360:1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Wig N, Chaudhary D, Sood NK, Sharma BK. Changing pattern of acute poisoning in adults: experience of a large north-west Indian hospital 1970-1989. Journal of the Association of the Physicians of India. 1997;45:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maniam T. Suicide and parasuicide in a hill resort in Malaysia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;153:222–225. doi: 10.1192/bjp.153.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hettiarachchi J, Kodithuwakku GC. Pattern of poisoning in rural Sri Lanka. Int.J Epidemiol. 1989;18:418–422. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.2.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. QJM. 2000;93:715–731. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.11.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somasundaram DJ, Rajadurai S. War and suicide in northern Sri Lanka. Acta Psychiatr.Scand. 1995;91:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1995.tb09733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hutchinson G, Daisley H, Simeon D, Simmonds V, Shetty M, Lynn D. High rates of paraquat-induced suicide in southern Trinidad. Suicide Life Threat.Behav. 1999;29:186–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cantor CH. Suicide in the Western World. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2000. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platt S, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, et al. Parasuicide in Europe: the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. I. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1992;85:97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawton K, Casey D, Hall S, Simkin S, Harriss L, Bale E, Bond A, Shepherd A. Deliberate self-harm in Oxford 2001. Oxford: The Centre For Suicide Research, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips MR, Li X, Zhang Y. Suicide rates in China, 1995-99. Lancet. 2002;359:835–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger LR. Suicides and pesticides in Sri Lanka. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:826–828. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.7.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994- 9. BMJ. 2003;326:1121–1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh D, Jit I, Tyagi S. Changing trends in acute poisoning in Chandigarh zone: a 25-year autopsy experience from a tertiary care hospital in northern India. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1999;20:203–210. doi: 10.1097/00000433-199906000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowles JR. Suicide in Western Samoa: an example of a suicide prevention program in a developing country. In: Diekstra RFW, et al., editors. Preventative strategies of suicide. Leiden: E J Brill; 1995. pp. 173–206. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abeysinghe RM. A Study of Pesticide Poisoning in an Agricultural Community. University of Colombo; 1992. MSc Community Medicine Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clarke RV, Lester D. Suicide: Closing the Exits. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. Explaining choice of method; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreitman N. The coal gas story. United Kingdom suicide rates, 1960-71. Br.J.Prev.Soc.Med. 1976;30:86–93. doi: 10.1136/jech.30.2.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wells N. Suicide and Deliberate Self Harm. White Crescent Press Ltd.; 1981. pp. 1–56. Office of Health Economics. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver RG, Hetzel BS. Rise and fall of suicide rates in Australia: relation to sedative availability. Med J Aust. 1972;2:919–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anon. As easy as buying a toothbrush. The Lancet. 1993;341:1375–1376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Household firearm ownership and suicide rates in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13:517–524. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amos T, Appleby L, Kiernan K. Changes in rates of suicide by car exhaust asphyxiation in England and Wales. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31:935–939. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Department of Health . National suicide prevention strategy for England. London: Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organisation . The World Health Report. Mental Health: New Understanding. New Hope: 2001. pp. 1–178. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor SJ, Kingdom D, Jenkins R. How are nations trying to prevent suicide? An analysis of national suicide prevention strategies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1997;95:457–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb10132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunnell D, Murray V, Hawton K. Use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for suicide and nonfatal poisoning: worldwide patterns of use and misuse. Suicide Life Threat.Behav. 2000;30:313–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hawton K, Townsend E, Deeks J, et al. Effects of legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol and salicylate on self poisoning in the United Kingdom: before and after study. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:1203–1207. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeyaratnam J. Acute pesticide poisoning: a major global health problem. World Health Stat.Q. 1990;43:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO . The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. WHO; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eddleston M, Sheriff MH, Hawton K. Deliberate self-harm in Sri Lanka: an overlooked tragedy in the developing world. BMJ. 1998;317:133–135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7151.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kenmore PE. Integrated pest management. Introduction. Int J Occup.Environ.Health. 2002;8:173–174. doi: 10.1179/107735202800338759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hruska AJ, Corriols M. The impact of training in integrated pest management among Nicaraguan maize farmers: increased net returns and reduced health risk. Int J Occup.Environ.Health. 2002;8:191–200. doi: 10.1179/107735202800338777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts DR, Karunarathna A, Buckley NA, Manuweera G, Sheriff MHR, Eddleston M. Influence of Pesticide Regulation on Acute Poisoning Deaths in Sri Lanka. WHO Bulletin. 2003 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abu al-Ragheb SY, Salhab AS. Pesticide mortality. A Jordanian experience. Am J Forensic Med.Pathol. 1989;10:221–225. doi: 10.1097/00000433-198909000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunnell D. Reporting Suicide. Medicine in the Media. British Medical Journal. 1994;308:1446–1447. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onyon LJ, Volans GN. The epidemiology and prevention of paraquat poisoning. Hum.Toxicol. 1987;6:19–29. doi: 10.1177/096032718700600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amarasingham RD, Lee H. A review of poisoning cases examined by the Department of Chemistry, Malaysia, from 1963 to 1967. The Medical Journal of Malaya. 1969;23:220–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senewiratne B, Thambipillai S. Pattern of poisoning in a developing agricultural country. Br.J Prev.Soc.Med. 1974;28:32–36. doi: 10.1136/jech.28.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nandi DN, Mukherjee SP, Banerjee G, Ghosh A, Boral GC, Chowdury A, et al. Is suicide preventable by restricting the availability of lethal agents? A rural survey of West Bengal. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 1979;21:251–255. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wohlfahrt DJ. Paraquat poisoning in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 1981;24:164–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilks MF. Paraquat poisoning. Lancet. 1999;353:321–322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74910-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.SUPRE . Prevention of Suicidal Behaviours: A Task for all. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360:1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.About the International Programme on Chemical Safety. 2003. http://www.who.int/pcs/pcs_about.html.

- 53.WHO . Pesticide poisoning database in SEAR countries: Report of a regional workshop. New Delhi: 2001. pp. 22–24. Document SEA-EH-534. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Report of the second meeting of the advisory group of the epidemiology of pesticide poisoning project. Geneva: WHO HQ; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bull D. A growing problem: pesticides and the third world poor. Oxford: Oxfam; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dinham B. The pesticide hazard: A global health and environmental audit. London: Zed Books; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murray DL. Cultivating Crisis: The Human Cost of Pesticides in Latin America. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sass R. Agricultural “killing fields”: the poisoning of Costa Rican banana workers. Int J Health Serv. 2000;30:491–514. doi: 10.2190/PNKW-HAPB-QJBA-LLL4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]