Abstract

A series of new bisphenol derivatives bearing allylic moieties were synthesized as potential analogs of honokiol and/or magnolol. Certain compounds exhibited specific anti-proliferation activity against SVR cells and moderate anti-HIV-1 activity in primary human lymphocytes. Compound 5h was the most potent compound and its anti-tumor activity was evaluated in vivo.

In the fight against diseases and body disorders, plants extracts were exploited heavily by ancient civilizations. Thus, Chinese medicine has developed over a period of several thousand years many preparations which are used in the treatment of a wide variety of clinical diseases. It is only in the last century that efforts have been made to isolate and identify specific active chemicals from these “cocktails”. Saiboku-to, a mixture of natural products that contains magnolia bark, has been historically used for clinical depression, anxiety as well for thrombotic stroke. The principal active components of the mixture appear to be the neolignans magnolol 1 and honokiol 2.1 These two compounds demonstrated various biological properties including anti-oxidant and antidepressant activities.2 Recent studies in our laboratory also indicate that honokiol induced apoptosis in tumor cells,3,4 inhibits angiogenesis5 and has weak in vitro anti-HIV-1 activity.6 This combination of biological properties justifies further studies in order to increase the potency of these lead compounds and to understand their mechanism of action. Even though, until now, only few analogs have been reported in the literature, it appears that honokiol and magnolol’s potent activities are attributed to the presence of hydroxyl and allylic groups on a biphenolic moiety.7 Thus, to clarify a structure-activity relationship and to improve the potent activity of these two compounds, some simple allylated biphenol analogs and some “flexible” allylated biphenolic derivatives varying a linker between the two aromatic rings were prepared. Herein, we report the preparation of various compounds 5a-i and 10, their antiviral and anti-proliferatives activities in vitro and the in vivo activity of compound 5h.

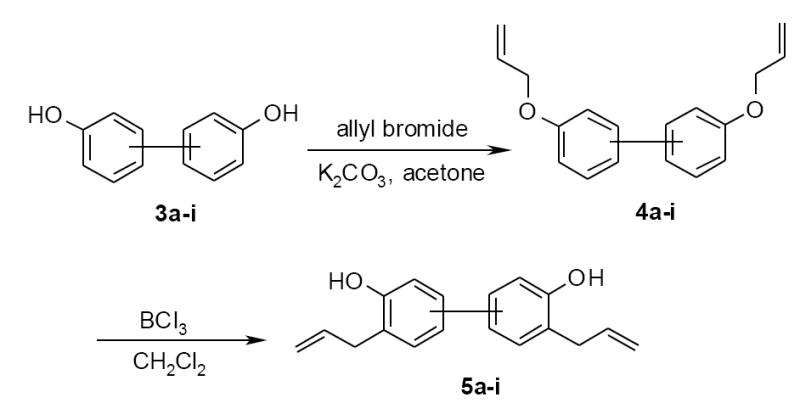

The syntheses of 5a-i were accomplished with phenolic O-allylation of compounds 3a-i followed by Claisen rearrangement. Therefore, biphenol derivatives 3a-i were treated with excess of allyl bromide in the presence of potassium carbonate to afford corresponding bis(allyloxy)-biphenyls 4a-i. The following Claisen rearrangement of 4a-i was then performed in dichloromethane using 1.5 eq. of a 1M solution of BCl3 to give the desired 3,3’-bisallylbiphenol 5a-i (scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

The biphenols 3b-i were commercially available but, biaryl 3a was synthesized through a Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura reaction (Scheme 2). Thus the coupling between 2-iodophenol 6 and the phenol 4-boronic acid 7 was achieved by using Pd(OAc)2 (10 mol%), dppf (diphenylphosphino ferrocene) (10 mol%) in presence of K2CO3 (3.0 equiv.) in THF at room temperature.

Scheme 2.

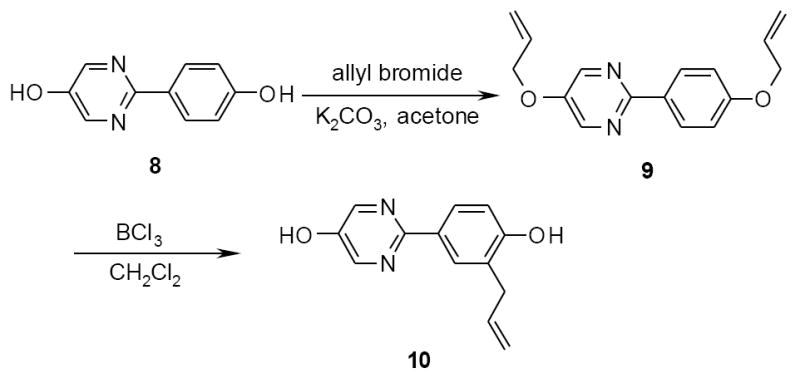

Interestingly, the allylation/Claisen procedure applied to the 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-pyrimidinol 8 did not give the expected diallylated derivative, but produced the monoallylated compound 10 (Scheme 3). In fact, if the migration of the allyl group is generally the main product of the Claisen reaction,8 the cleavage can be the dominant reaction mode in particular with electron deficient rings such as the case of pyrimidine.

Scheme 3.

Cytotoxic activities

The antitumoral activities of compounds 5a-i and 10 were conducted by measuring their effect on the survival and proliferation of the immortalized endothelial cell line SVR.9 Briefly, SVR cells (104) were plated in 24-well dishes. The next day, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the inhibitors or controls. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 72 h,10 and cell number was determined in triplicate using a Coulter Counter (Hialeah, FL). Immortalized and K-Ras transformed rat epithelial cells (RIEpZip and RIEpZipK-Ras12V) were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2, in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (RIE).11,12 Cells were plated at 105/well in six-well plates. Cells were treated with either vehicle (≤ 0.05% DMSO in medium) or increasing concentrations (10 and 15 μg/ml) of honokiol analogs (from a 10 mg/ml stock) and observed for morphology changes after 24 h.

Modifying the position of allyl and hydroxyl groups around the simple biphenyl skeleton, as with compounds 5b and 5c, reduced the cellular growth (Table 1), but did not demonstrate any activity enhancement compared with honokiol (57% and 56% inhibition at 15 mg/ml, respectively for 5b and 5c, compared to 85% inhibition for honokiol). The mono-allylated compound 10 was almost completely inactive in all cell lines. Introduction of a linker between the two phenyl rings, making larger, but also more “flexible” molecules, is an interesting way to determine the influence of the size of the compound on the target. Initial results indicated that introduction of a one carbon bridge bearing a dimethyl (5e) or a pyridine group (5h) significantly decreased cytotoxicity in SVR cells. On the other hand, the presence of groups such as methylene (5d), methylenecyclohexyl (5f) or dichloroalkene (5g) provided similar antiproliferative activities, but without selectivity compared to normal human lymphocytes [peripheral blood mononuclear (PBM) cells]. Compound 5i was quite potent and showed an excellent antiproliferative response in SVR cells (68% and 89% inhibition at 10 and 15 μg/mL) and an IC50 of 3.4 μM in human T-cell lymphoma cells (CEM). At the same time, no toxicity was detected in normal human PBM cells. This selectivity made this compound a good candidate for further evaluation in a small animal model. To determinate whether compound 5i exhibits anti-tumor activity in vivo, SVR cells were injected into flank of 6-week-old nude male mice. When tumors became visible at approximately 1 week after inoculation, mice received 3 mg/day compound 5i or vehicle control intraperitoneally. Treatment up to 100 mg/kg for 30 days did not inhibit the tumor growth, but also did not result in any toxicity compared with vehicle control.

Table 1.

Inhibition of SVR proliferation, anti HIV-1 activity and cytotoxicity against human PBM, CEM and Vero cells.

| Compound | Structure | Inhibition of SVR cells at 10 μg/mLa | Inhibition of SVR cells at 15 μg/mLa | Anti HIV-1 activity in PBM cells (μM) | Cytotoxicity (IC50, μM) in | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 | EC90 | PBM | CEM | Vero | ||||

| 1 |

|

60% | 77% | 69.3 | >100 | 38.6 | 99.5 | 50.6 |

| 2 |

|

60% | 85% | 3.3 | 22.7 | 16.1 | 10.9 | 22.5 |

| 5a |

|

74% | 81% | 23.4 | 81 | 36.7 | 17.9 | 11.4 |

| 10 |

|

4.4% | 10% | >100 | >100 | 31.9 | >100 | >100 |

| 5b |

|

41% | 57% | 34.8 | 63.0 | 45.9 | 10.4 | 19.8 |

| 5c |

|

45% | 56% | 19.4 | 66.4 | >100 | 23.0 | 83.2 |

| 5d |

|

75% | 74% | 13.6 | 35.1 | 33.7 | 15.1 | 1.9 |

| 5e |

|

33% | 57% | 4.1 | 47.3 | >100 | 5.8 | 13 |

| 5f |

|

63% | 79% | 36.5 | 67.2 | 55.4 | 11.0 | 12.5 |

| 5g |

|

54% | 76% | 14.3 | 48.8 | 43.6 | 17.1 | 12.1 |

| 5h |

|

25% | 46% | 35.0 | 67.2 | 16.8 | 16.5 | 14.8 |

| 5i |

|

68% | 89% | 9.5 | 30.9 | >100 | 3.4 | 3.7 |

to convert from μg/mL to μmol/L (μM), concentration have to be multiplied by an average of 3.2

Antiviral activities

Since honokiol 2 itself is a modest antiviral agent against HIV-1, the activities of analogs 5a-i and 10 were also evaluated and the results expressed as a median effective concentration or EC50 (Table 1). The antiviral13 and cytotoxicity14 assays were performed as previously described. Compared to honokiol 2, compounds 5a-d, 5f-h and 10 appeared less potent against HIV-1 in human PBM cells and only compounds 5e and 5i showed moderate activities close to honokiol’s activity (EC50 of 4.1 and 9.5 μM respectively, compared to 3.3 μM for honokiol)

In conclusion, the discovery of the antiproliferative potency of compounds 5d, 5f, 5g and especially 5i provides new insights on the synthesis and the evaluation of new biphenyl-linked compounds. As a result of the above studies, further modifications between the two phenol moieties would be envisaged in order to generate more potent and selective analogs with improved in vivo activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant 5P30-AI-50409 (CFAR), 5R37-AI-041980 and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- 1.Maruyama Y, Kuribara H, Morita M, Yuzurihara M, Weintraub ST. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:135–138. doi: 10.1021/np9702446. and references cited herein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lo YC, Teng CM, Chen CF, Chen CC, Hong CY. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:549–553. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nakazawa T, Yasuda T, Ohsawa K. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55:1583–1591. doi: 10.1211/0022357022188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Teng CM, Chen CC, Ko FN, Lee LG, Huang TF, Chen YP, Hsu HY. Thromb Res. 1988;50:757–765. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(88)90336-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Teng CM, Yu SM, Chen CC, Huang YL, Huang TF. Life Sci. 1990;47:1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90176-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battle TE, Arbiser J, Frank DA. Blood. 2005;106(2):690–697. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishitsuka K, Hideshima T, Hamasaki M, Raje N, Kumar S, Hideshima H, Shiraishi N, Yasui H, Roccaro A, Richardson P, Podar K, Le Gouill S, Chauhan D, Tamura K, Arbiser J, Anderson KC. Blood. 2005;106(5):1794–1800. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bai X, Cerimele F, Ushio-Fukai M, Waqas M, Campbell PM, Govindarajan B, Der CJ, Battle T, Frank DA, Ye K, Murad E, Dubiel W, Soff G, Arbiser JL. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35501–3557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302967200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amblard F, Delinsky D, Arbiser JL, Schinazi RF. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3426–3427. doi: 10.1021/jm060268m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esumi T, Makado G, Zhai H, Shimizu Y, Mitsumoto Y, Fukuyama Y. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:2621–2625. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kong Z-L, Tzeng S-C, Liu Y-C. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lutz RP. Chem Rev. 1984:206–247. [Google Scholar]; Martin Castro AM. Chem Rev. 2004:2939–3002. doi: 10.1021/cr020703u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arbiser JL, Panigrathy D, Klauber N, Rupnick M, Flynn E, Udagawa T, D’Amato RJ. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:925–929. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaMontagne KR, Jr, Moses MA, Wiederschain D, Mahajan S, Holden J, Ghazizadeh H, Frank DA, Arbiser JL. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1937–1945. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64832-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldham SM, Clark GJ, Gangarosa LM, Coffey RJ, Jr, Der CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6924–6928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pruitt K, Pestell RG, Der CJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40916–40924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schinazi RF, Sommadossi JP, Saalman V, Cannon DL, Xie M-W, Hart GC, Hahn EF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1061. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuyver LJ, Lostia S, Adams M, Mathew J, Pai BS, Grier J, Tharnish P, Choi Y, Chong Y, Choo H, Chu CK, Otto MJ, Schinazi RF. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3854. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.12.3854-3860.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]