Abstract

Quinoline-2,4-dicaboxylic acids (QDCs) bearing lipophilic substituents in the 6- or 7-position were shown to be inhibitors of the glutamate vesicular transporter (VGLUT). Using the arrangement of the QDC lipophilic substituents as a template, libraries of X1X2EF and X1X2EW tetrapeptides were synthesized and tested as VGLUT inhibitors. The peptides QIEW and WNEF were found to be the most potent. Further stereochemical deconvolution of these two peptides showed dQlIdElW to be the best inhibitor (Ki = 828 ± 252 μM). Modeling and overlay of the tetrapeptide inhibitors with the existing pharmacophore showed that H-bonding and lipophilic residues are important for VGLUT binding.

L-Glutamate is stored in synaptic vesicles prior to its depolarization-triggered, calcium-dependent release from neuron terminals1-4 and is transported into the vesicles in an ATP-dependent manner by the glutamate vesicular transporter (VGLUT). Unlike the plasma membrane neurotransmitter transporters, VGLUT is stimulated by low, physiologically relevant concentrations of Cl- ion,5 although the contribution of the Cl- - to ΔpH has been debated.2-7 VGLUT is specific for glutamate but it is low affinity (Km = 1 to 3 mM), which contrasts with the plasma membrane transporters that are specific for glutamate but high affinity (Km = 5-50 μM).8-11 To differentiate between these transporters, potent and selective inhibitors of VGLUT are needed.

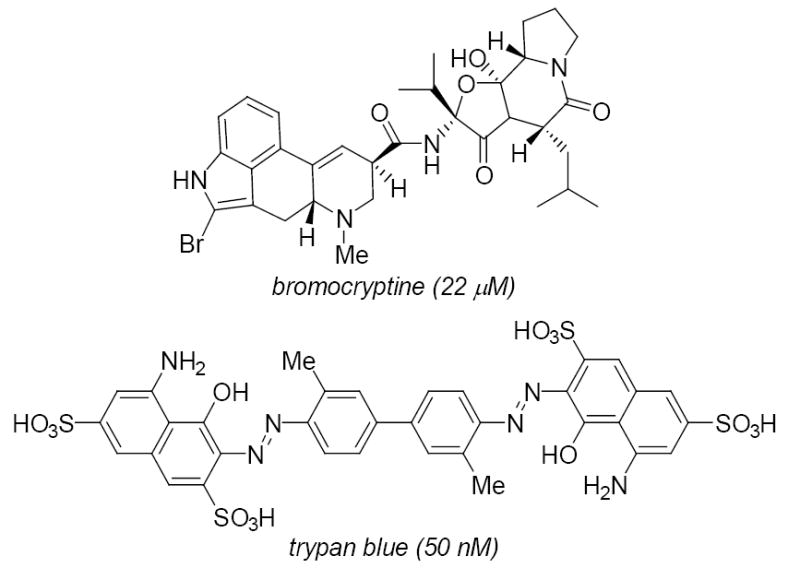

The main VGLUT inhibitor structures have been recently reviewed.1 In brief, aspartate5,12 and simple glutamate analogs are not good inhibitors of VGLUT, whereas some kynurenate analogs showed modest activity. The alkaloid bromocryptine (ki = 20 μM) and certain azo dyes (e.g., trypan blue) are among the most potent VGLUT inhibitors (Fig. 1).13 We reported a systematic, structure-activity study of quinoline 2,4-dicarboxylic acids (QDCs; Fig . 2) as inhibitors14, 15 that seeded the development of the first pharmacophore model1 for VGLUT and the use of QDC’s as a key motif for future inhibitor design and substituent variation.

Fig 1.

Structures of VGLUT inhibitors

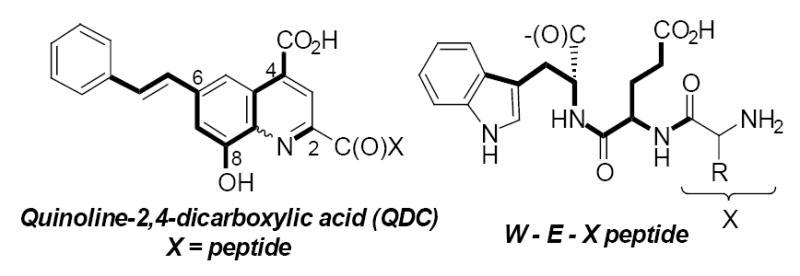

Fig 2.

Proposed QDC inhibitor structural relationship to peptides.

Some of the more potent QDC-based inhibitors contained lipophilic groups at position 6 or a hydroxyl at position 8. Combining these favorable substituents into the QDC template led to the observation that this pattern overlays with a peptide that contains (HO2C)WEX(NH2) (Fig. 2). The very weak basicity of the QDC nitrogen also suggested that a peptide amide might be an appropriate isostere. This prompted an investigation of small peptides that might be capable of binding VGLUT. Peptide-based inhibitors are also possible leads to uncover protein interactions.

Based on observations that QDCs containing an embedded glutamate moiety and lipophilic substituents (phenyl, styryl, etc.) confer greater inhibitory activity, a tetrapeptide library was envisioned in which the C-terminus amino acid was occupied by either tryptophan (W) or phenylalanine (F) to represent the lipophilic substituent and the adjacent position occupied by a glutamate (E) residue. The N-terminus and second residue (X1 and X2) were systematically varied to investigate how these positions could enhance binding (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Tetrapeptide design based on the QDC-template.

To further refine our binding requirements and increase the overall library diversity, either d- or l-amino acids were used. Further rationale for the incorporation of d-glutamate into the libraries is based on the modest activity of this enantiomer as an inhibitor of VGLUT.11 Overall, stereoisomeric tetrapeptides X1X2EW(F) were prepared and evaluated as VGLUT inhibitors (Fig. 3; Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhibition of VGLUT by Tetrapeptides1

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 |

3H-lGlu uptake

(% of control)2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library 1 | ||||

| AA3 | AA | E | W | |

| Q | AA | E | W | 56 ± 1% |

| Q | W | E | W | 66 ± 4% |

| Q | I | E | W | 38 ± 5% |

| D-Q | D-I | L -E | D-W | 35 ± 3% |

| L-Q | D-I | L-E | D-W | 28 ± 3% |

| Library 2 | ||||

| AA | AA | E | F | |

| N | AA | E | F | 63 ±17% |

| W | AA | E | F | 36 ± 2% |

| W | N | E | F | 13 ± 3% |

| D-W | L-N | D-E | D-F | 41 ± 1% |

| Other | ||||

| Congo Red (2 μM) | 31 ± 2% | |||

Tetrapeptides tested as racemic mixtures at 2mM.

Control rate for 3H-L-glutamate uptake was 1847±130(n=17) pmol/min/mg protein.

AA = 19 different amino acids.

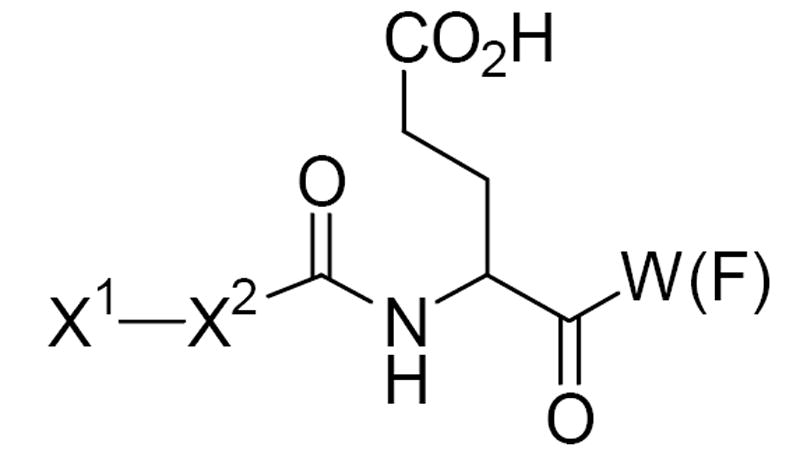

Peptide Synthesis. 16 Tetrapeptides were synthesized according to Scheme 1 and structures determined by NMR and/or mass spectrometry.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of target tetrapeptides containing a glutamate at position 3.

Inhibition of VGLUT by Tetrapeptides. 17 Screening of the peptide libraries as VGLUT inhibitors was carried out using 3H-glutamate as substrate and the ability of test compounds to block the uptake of 3H-glutamate into synaptic vesicles isolated from rat forebrain. Tetrapeptide sub-libraries of the type X1X2EW (Library 1) or X1X2EF (Library 2), where X1 and X2 were varied as amino acids (AA) in D- or L- form (except cysteine), and where the identity of X1 was known, were tested as inhibitors of VGLUT.18 The sub-libraries were screened and the pools showing the most inhibition of uptake were deconvoluted to identify X2 residues (Table 1).

We next reasoned that the various stereoisomers comprising a deconvoluted sublibrary would be approximately equal, allowing the assay to be a reasonable guide to selection of the pools used for further deconvolution. In library 1, the only tetrapeptide sublibrary to inhibit glutamate uptake at VGLUT were structures with X1 = Q (56% uptake). Systematic screening of the QX2EW tetrapeptides indicated the order of inhibitory potency for position X2 as I ≫ Q, W> N. Therefore, QIEW was selected for deconvolution into its stereoisomers, six of which inhibited the uptake of glutamate: ldld (28%), ddld (35%), lddd (60%), dddd (63%), ldll (69%), and lldl (82%). The QWEW panel was active but allowed 66% residual transport. Based on the lesser activity and solubility limits, this panel was not deconvoluted for further analysis.

The results from Library 2 showed that aryl or amide residues are preferred at position X1 (N-term) with less uptake allowed following the order W (36%) < N (63%). As found with Library 1, Library 2 showed activity with a wider range of possible residues occupying position 2. For X2 in Library 2 (WX2EF), the order was N (13%) > Q, W > I, F > H. As with library 1, the WNEF tetrapeptide was selected for further stereoisomer deconvolution. Interestingly, the individual enantiomers were not as active as the mixture and only one isomer, dWlNdEdF showed inhibition of glutamate uptake (41%).

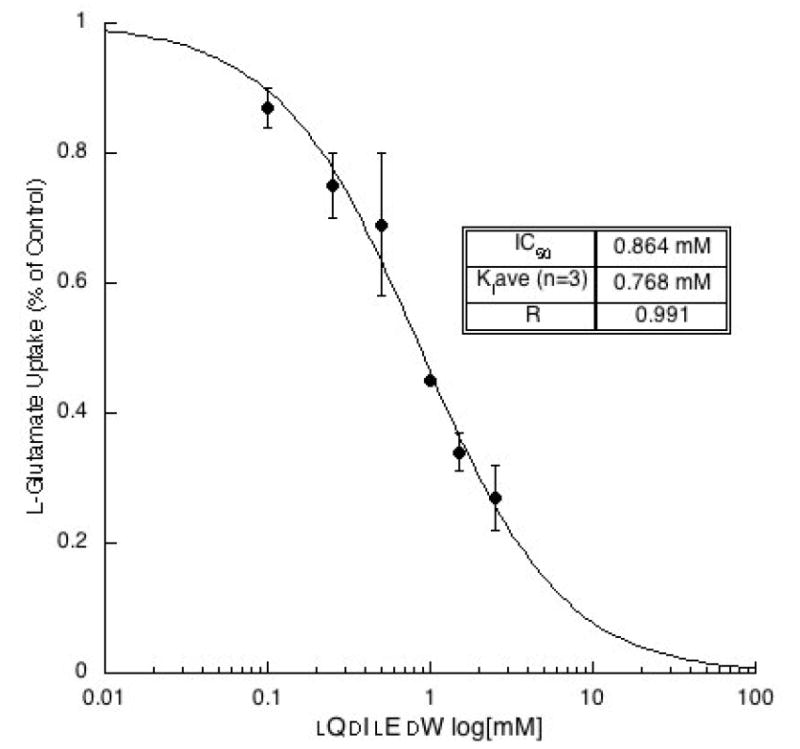

To better understand the inhibitory activity, a more thorough analysis of dQlIdElW was conducted. Using the Cheng-Prusoff relationship to estimate from IC50 values, the Ki was determined from non-linear regression analyses of sigmodial inhibitory dose-response curves. The inhibitory dose-response for dQlIdElW was plotted (Fig. 4) and the Ki was determined to be 828 ± 252 μM as the mean ± s.e.m (n = 3). In separate experiments, it was determined that neither QIEW nor WNEF blocks v-ATPase activity in rat synaptic vesicles at the concentrations tested for VGLUT inhibition.

Fig 4.

Demonstration of the inhibitory dose-response dependency of dQlIdElW on the uptake of 3H-l-glutamate (0.25 mM) into rat brain synaptic vesicles. Representative plot yielded a Ki = 0.465 mM. The control rate for L-glutamate uptake was 1912 nmol/min/mg protein and Km = 2.1 mM.

Although a glutamic acid is fixed at position 3 in all libraries, charged residues at positions X1 and X2 resulted in poor VGLUT inhibition. For X2, both libraries prefer hydrophobic or amide-containing residues. Q, N, W, and I consistently appeared in the panels that showed inhibition of glutamate uptake. This finding both correlates with the structure of bromocryptine (Fig. 1),19 a ‘peptide containing’ alkaloid and with the reportedpharmacophore. Bromocryptine is a potent inhibitor that lacks an acidic side chain group like glutamate but contains homologous lipophilic residues along a peptide-like framework.

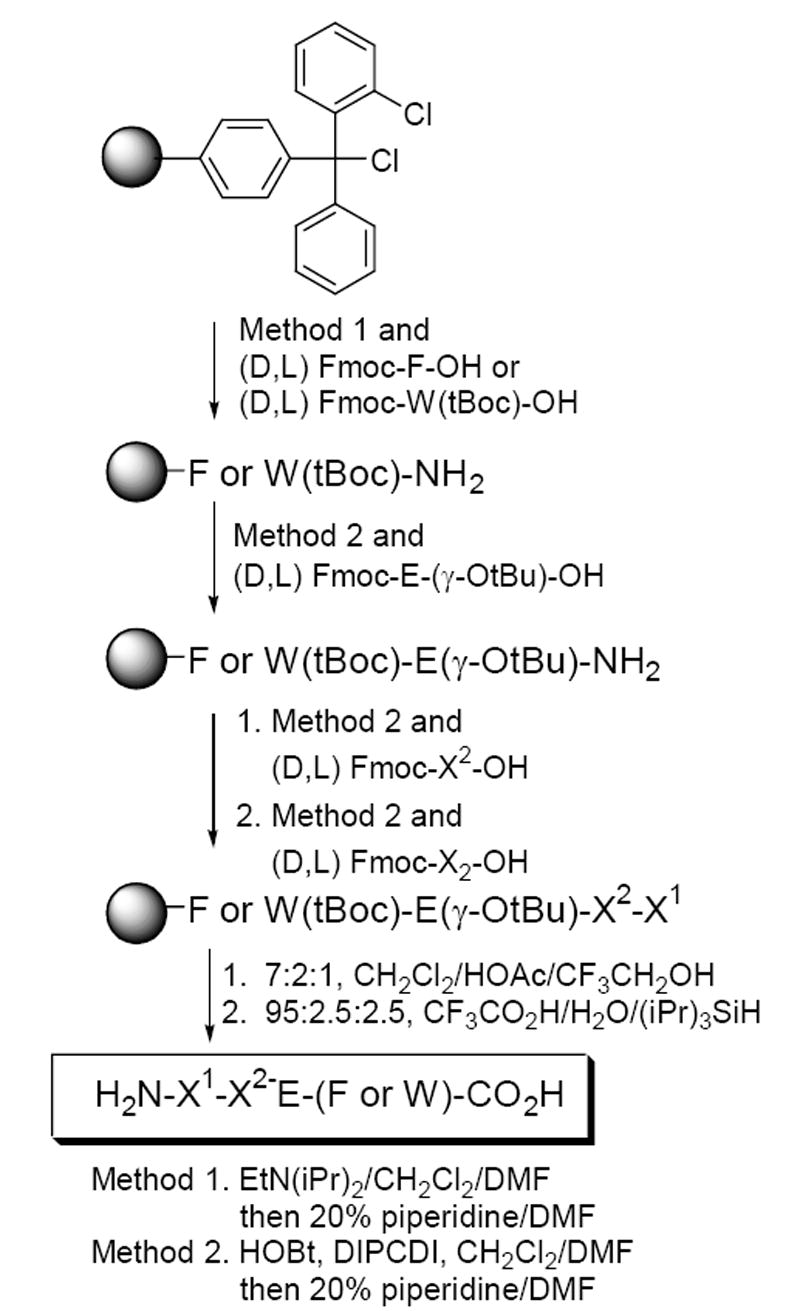

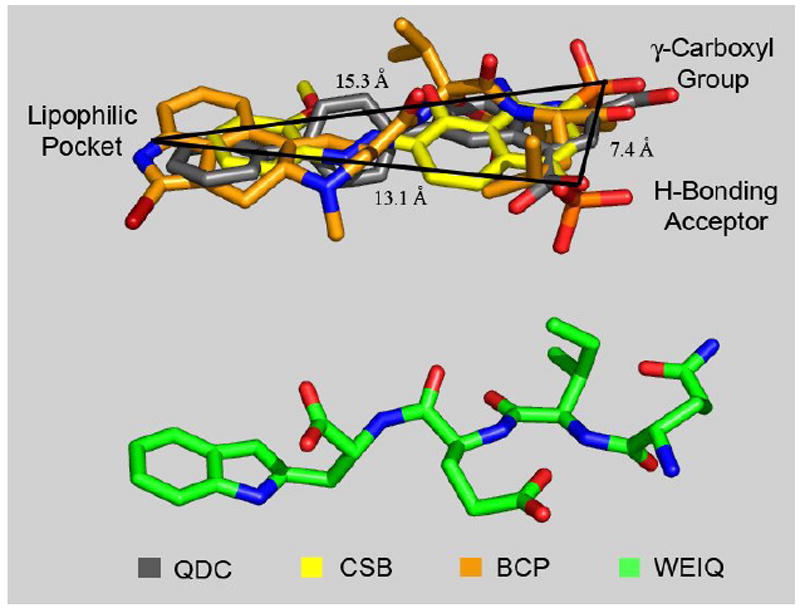

In an effort to gain insight into the plausible interactions with VGLUT as a function of the QDC-based ligand design features (Fig. 2) and the inhibition (Table 1, Fig. 3) an initial alignment of an extended conformation of the stereoisomer lQdIlEdW (C- to N-terminal) was made against our established inhibitor-based VGLUT pharmacophore model (Fig. 5).1

Fig. 5.

An extended conformation of the tetrapeptide lQdIlEdW (green) aligned in relation to a computationally-derived VGLUT superposition pharmacophore model1 composed with QDC (grey), one half of CSB (yellow) and BCP (orange), in which the ligands are correlated together with defined common pharmacophore comparison points (γ-carboxyl group, H-bonding acceptor and lipophilic pocket). Inter-atomic distances noted.

The inhibitor pharmacophore model, derived using the automated three-dimensional (3D) ligand alignment protocol GASP (Tripos Inc., St. Louis), is defined with 6-(4’-biphenyl)-quinoline-2,4-dicarboxylate (QDC, grey), one half of the symmetric structure of Chicago Sky Blue (yellow, CSB) and bromocryptine (orange, BCP). The superposition model describes three distinct regions in 3D space, including γ-carboxyl groups, H-bonding acceptors and lipophilic pocket moieties brought together with discrete inter-atomic distances between the regional points (Å values, Fig. 5). Since small peptides may assume a host of conformations, a plausible extended conformation of lQdIlEdW was selected for a VGLUT pharmacophore model comparison.

Analysis of the lQdIlEdW conformation alignment reveals that the N-terminal arginine (Q) correlates to the γ-carboxyl model region, the glutamic acid (E) side chain carboxyl moiety corresponds to the pharmacophore H-bonding acceptor group, and the C-terminal tryptophan (W) is consistent with the aromatic ring lipophilic pocket superposition area. Taken together, QIEW may block glutamate transport at VGLUT because it contains three ligand structural binding elements similar in 3D space to the more potent inhibitor ligand pharmacophore groups. Although the lesser potency of QIEW likely results from the conformational flexibility, its identity as a VGLUT inhibitor is consistent with the basic QDC-template peptide design strategy (Figure 2).

Moreover, examination of the Q-X2-E-W library reveals an enhanced peptide inhibition efficacy when X2 = isoleucine (I). Thus, ligands with terminal aromatic ring groups and an additional lipophilic side chain residue (e.g., W and I of QIEW; W and F of WNEF, not shown) might be related to the distinct dual lipophilic moieties (the terminal aromatic rings and distal propyl groups) of the more potent VGLUT inhibitor bromocryptine. Collectively, the lipophilic peptide and bromocryptine moieties could be important structural facets for enhanced VGLUT inhibition. Full conformational analyses of QIEW and WNEF and their superposition within the pharmacophore model are currently underway to discern the relative 3D arrangement of the lipophilic groups.

The discovery of tetrapeptide inhibitors raises the possibility that they may represent protein motifs that may bind VGLUT. BLAST analysis (rodentia)20,21 matched a Ca+-transporting ATPase (WNEF), neuroprotective protein (QIEW), and vasohibin (QIEW). We are currently examining the possibility of protein binding to VGLUT using these leads.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by grants from the NIH NS38248 (CMT) and P20 RR15583 from the COBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources. We are grateful for support to the Molecular Computational Core Facility (NIH NOT-RR-02-005) and expert assistance of Rohn Wood and Dr. Wes Smith.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and Notes

- 1.Thompson CM, Davis E, Carrigan CN, Cox HD, Bridges RJ, Gerdes JM. Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2041. doi: 10.2174/0929867054637635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fykse EM, Fonnum F. Neurochem Res. 1996;21:1053. doi: 10.1007/BF02532415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maycox PR, Deckwerth T, Hell JW, Jahn R. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tabb JS, Kish PE, Van Dyke R, Ueda T. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolosker H, de Souza DO, de Meis L. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.20.11726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cidon S, Sihra TS. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartinger J, Jahn R. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett RD, Esslinger CS, Thompson CM, Bridges RJ. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:839. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bridges RJ, Lovering FE, Koch H, Cotman CW, Chamberlin AR. Neurosci Lett. 1994;174:193. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garlin AB, Sinor AD, Sinor JD, Jee SH, Grinspan JB, Robinson MB. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2572. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64062572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naito S, Ueda T. J Neurochem. 1985;44:99. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridges RJ, Kavanaugh MP, Chamberlin AR. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller BU, Blaschke M, Rivosecchi R, Hollmann M, Heinemann SF, Konnerth A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrigan CN, Bartlett RD, Esslinger CS, Cybulski KA, Tongcharoensirikul P, Bridges RJ, Thompson CM. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2260. doi: 10.1021/jm010261z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrigan CN, Esslinger CS, Bartlett RD, Bridges RJ, Thompson CM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:2607. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peptides were synthesized with DIPCDI/HOBt using Fmoc methodology on a Cl-Trt-Cl (2-chlorotrityl chloride) resin and cleaved from the resin bead by treatment with 4:1 CH2Cl2/HOAc for 3 h. Peptides were treated with TFA to remove protecting groups.

- 17.Vesicular transport was quantified as described Kish PE, Ueda T. Methods Enzymol. 1989;174:9. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)74005-2.Assays were initiated by the addition of 3H-L-glutamate ± inhibitors (0.01-5 mM) to the synaptic vesicles (approx. 0.1 mg protein). Rates of uptake were normalized to protein content

- 18.Highly lipophilic peptides displayed poor solubility and were first solubilized in acetonitrile and then diluted into the HEPES assay buffer.

- 19.Carlson MD, Kish PE, Ueda T. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altschul SF, Koonin EV. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:444. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D. J Nuc Acids Res. 1997;25:3389. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]