Abstract

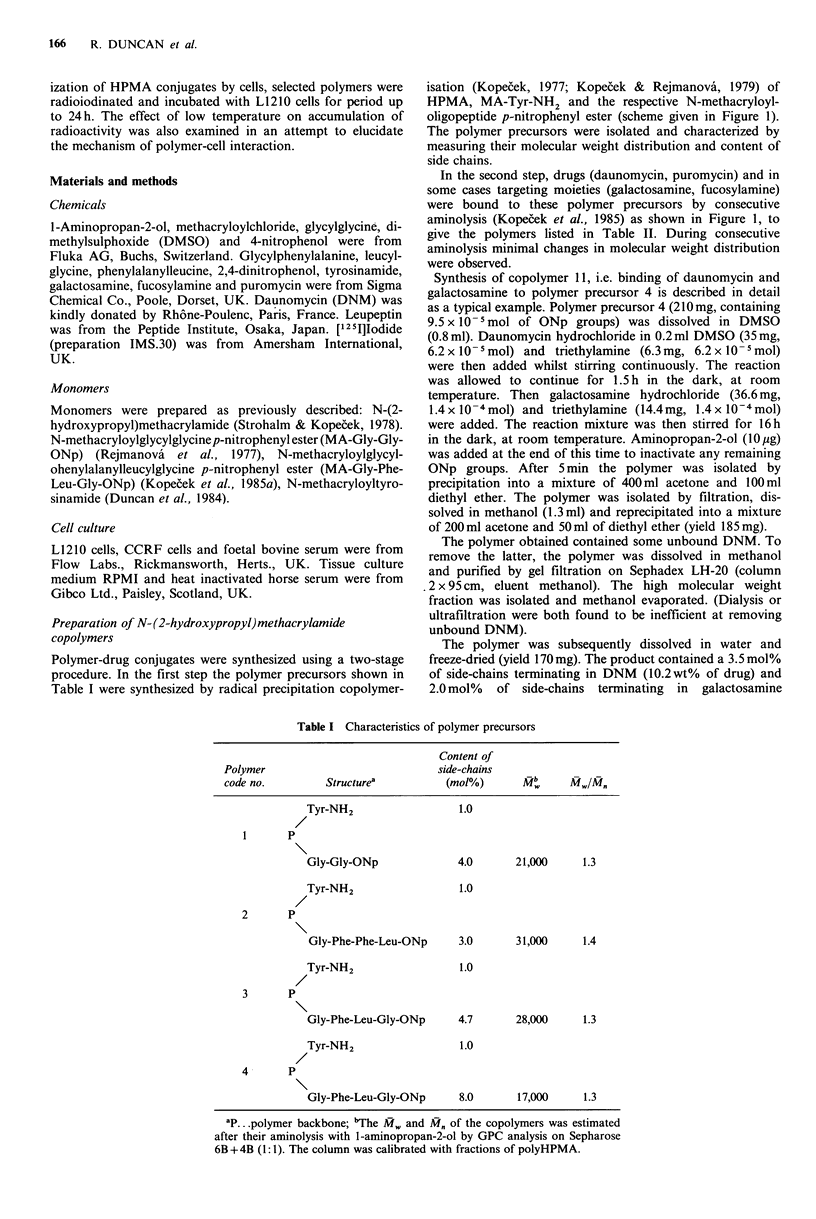

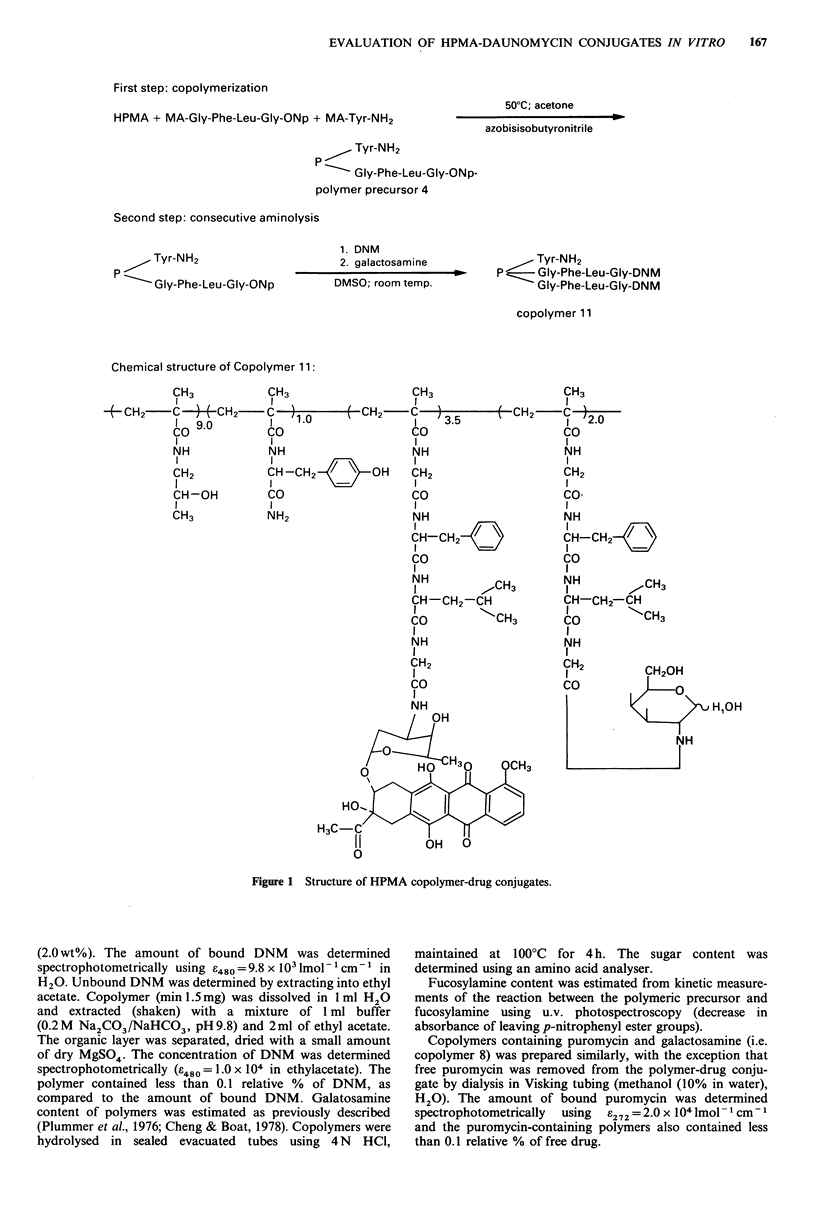

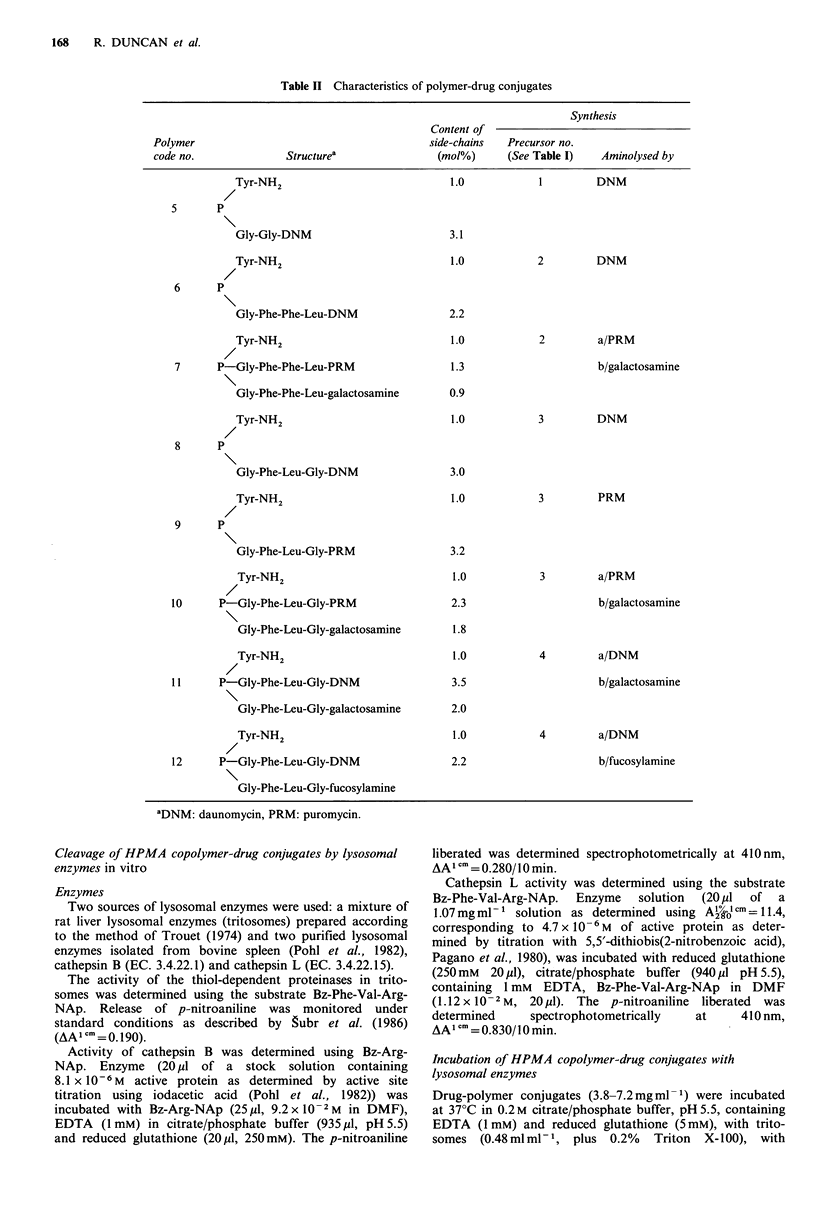

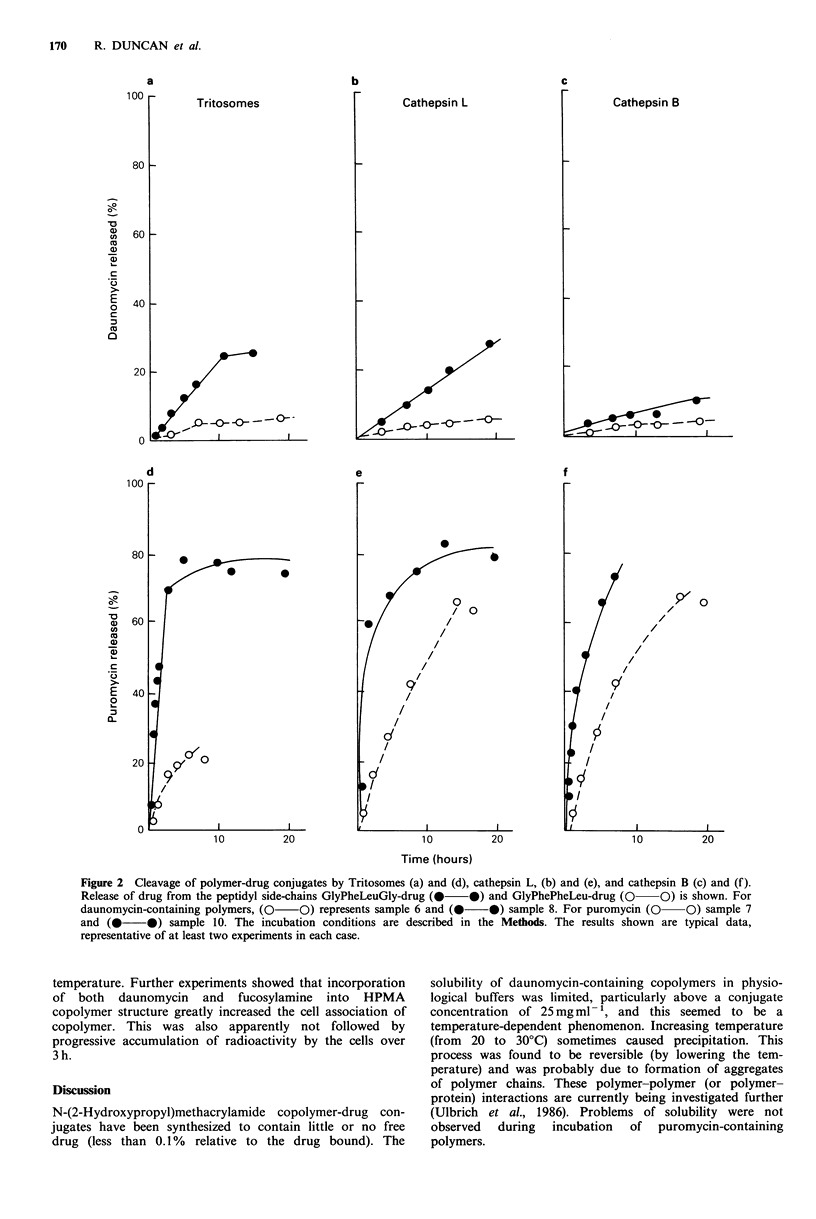

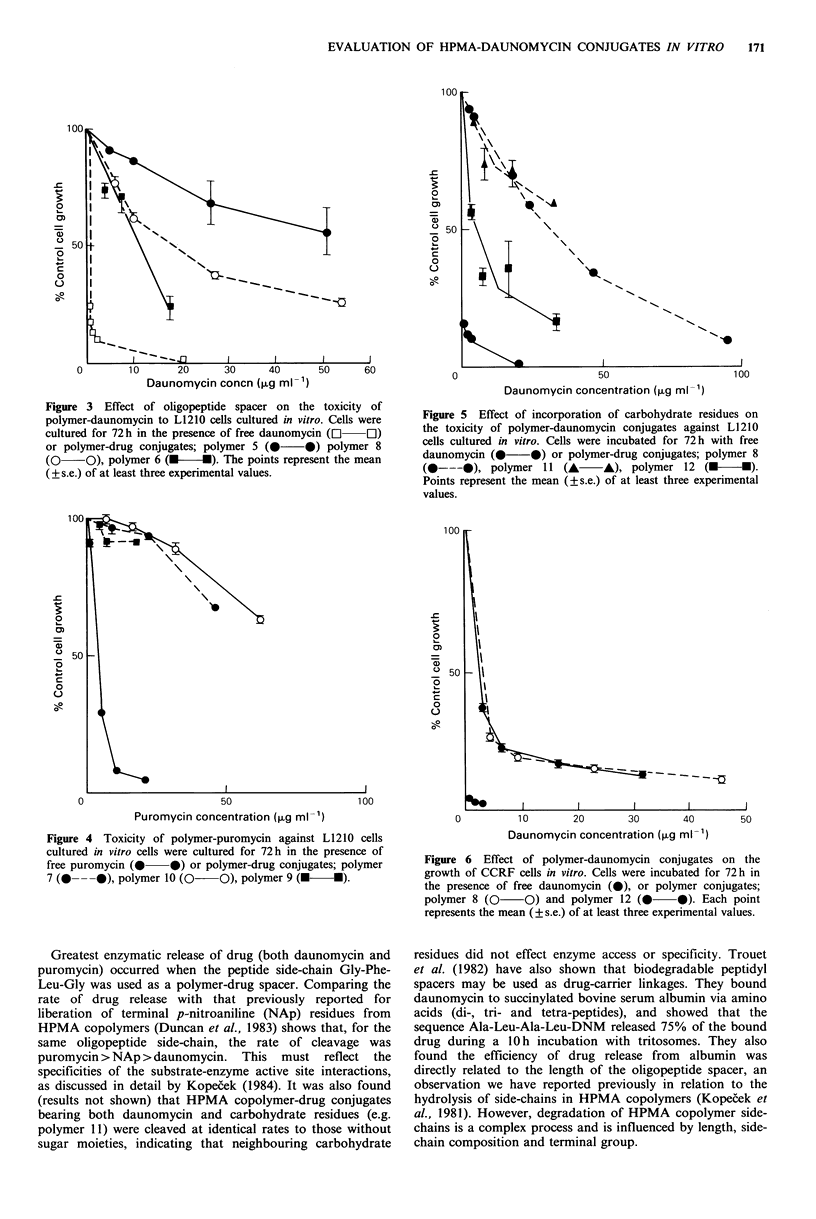

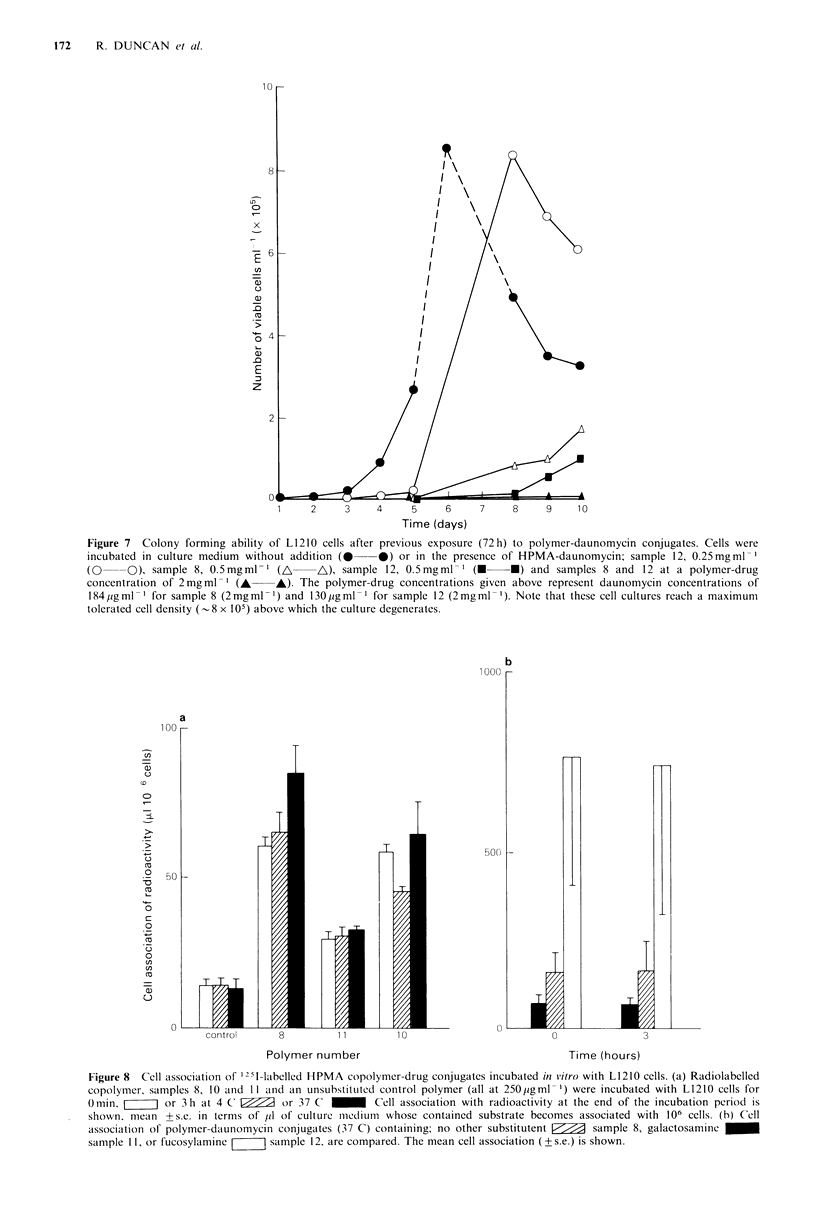

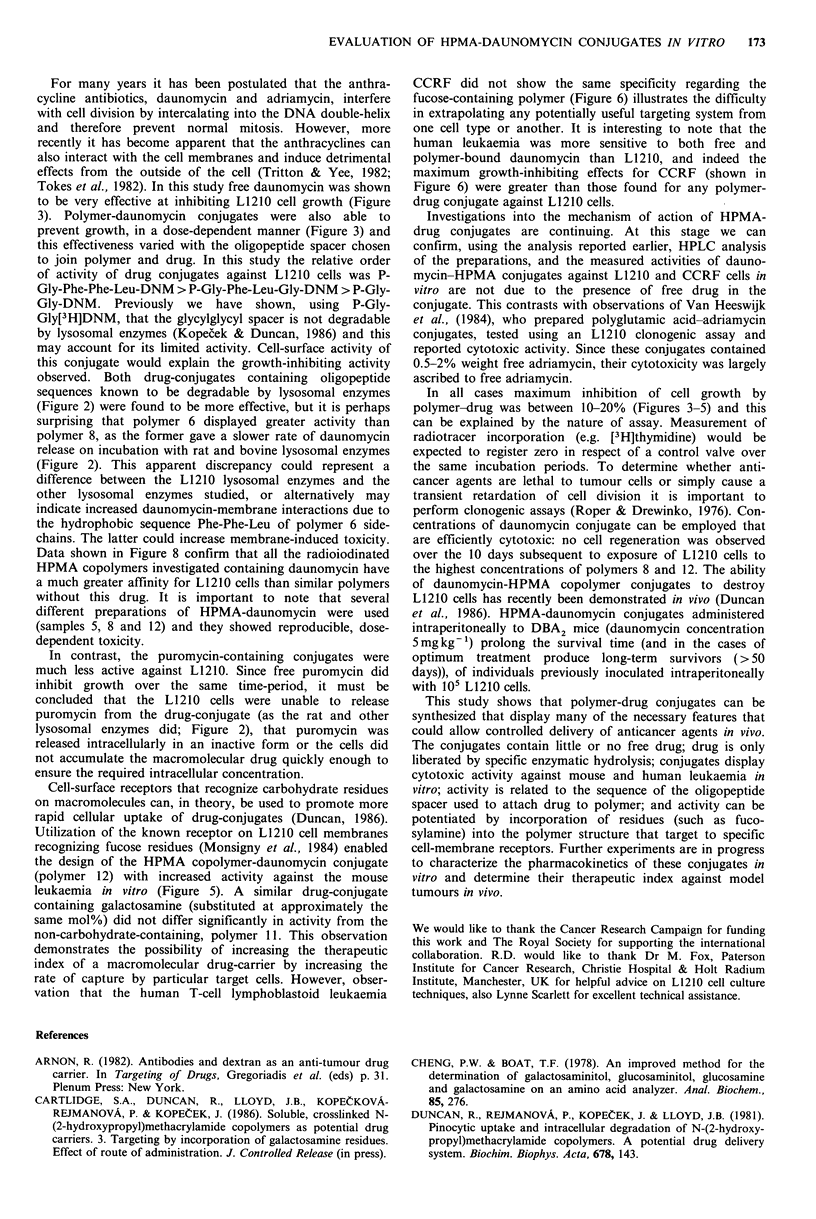

During recent years N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide (HPMA) copolymers have been developed as targetable drug carriers. These soluble synthetic polymers are internalized by cells by pinocytosis and they can be tailor-made to include peptidyl side-chains degradable intracellularly by specific lysosomal enzymes. Thus they provide the opportunity fo achieve controlled intracellular delivery of anticancer agents. The anthracycline antibiotic daunomycin, and protein synthesis inhibitor puromycin, were bound to HPMA copolymers via several different peptide side-chains, including Gly-Gly, Gly-Phe-Leu-Gly and Gly-Phe-Phe-Leu. Incubation of polymer-drug conjugates with isolated lysosomal enzymes (either a mixture of rat liver lysosomal enzymes or purified thiol-dependent lysosomal proteinases, cathepsins L and B) showed that significant release of drug occurred over 20 h, more than 20% of daunomycin and more than 80% of puromycin being liberated. To test their pharmacological activity conjugates were incubated with either the mouse leukaemia L1210, or the human lymphoblastoid leukaemia CCRF in vitro. The conjugates tested were all less effective than free daunomycin, but they showed differential toxicity against L1210 depending on the aminoacid sequence of their drug-polymer linkage. Inclusion of fucosylamine-terminating side-chains into the HPMA copolymer structure increased the affinity of conjugates for the L1210 cell membrane and resulted in increased toxicity. In contrast HPMA-daunomycin conjugates with or without fucosylamine affected CCRF cells equally, but this cell line was more sensitive than the mouse leukaemia to both free and polymer-bound daunomycin. Incubation of L1210 cells in polymer-bound daunomycin for 72 h, followed by plating cells out in low density in drug-free medium, showed that a concentration of polymer-bound drug (184 micrograms ml-1) could be selected to achieve a cytotoxic effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cheng P. W., Boat T. F. An improved method for the determination of galactosaminitol, glucosaminitol, glucosamine, and galactosamine on an amino acid analyzer. Anal Biochem. 1978 Mar;85(1):276–282. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90300-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R., Cable H. C., Rejmanová P., Kopecek J., Lloyd J. B. Tyrosinamide residues enhance pinocytic capture of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 May 25;799(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(84)90320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R., Kopecek J., Rejmanová P., Lloyd J. B. Targeting of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers to liver by incorporation of galactose residues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983 Feb 22;755(3):518–521. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(83)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R., Rejmanova P., Kopecek J., Lloyd J. B. Pinocytic uptake and intracellular degradation of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers. A potential drug delivery system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981 Nov 18;678(1):143–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(81)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R., Seymour L. C., Scarlett L., Lloyd J. B., Rejmanová P., Kopecek J. Fate of N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers with pendent galactosamine residues after intravenous administration to rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986 Jan 15;880(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(86)90120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoriadis G. Targeting of drugs: implications in medicine. Lancet. 1981 Aug 1;2(8240):241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecek J. Controlled biodegradability of polymers--a key to drug delivery systems. Biomaterials. 1984 Jan;5(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(84)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecek J., Rejmanová P., Duncan R., Lloyd J. B. Controlled release of drug model from N-(2-hydroxypropyl)-methacrylamide copolymers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;446:93–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb18393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsigny M., Roche A. C., Midoux P. Uptake of neoglycoproteins via membrane lectin(s) of L1210 cells evidenced by quantitative flow cytofluorometry and drug targeting. Biol Cell. 1984;51(2):187–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322x.1984.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano M., Engler R., Gelin M., Jayle M. F. Kinetic study of the interaction between rat haptoglobin and rat liver cathepsin B. Can J Biochem. 1980 May;58(5):410–417. doi: 10.1139/o80-054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer T. H., Jr A simplified method for determination of amino sugars in glycoproteins. Anal Biochem. 1976 Jun;73(2):532–534. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl J., Baudys M., Tomásek V., Kostka V. Identification of the active site cysteine and of the disulfide bonds in the N-terminal part of the molecule of bovine spleen cathepsin B. FEBS Lett. 1982 Jun 1;142(1):23–26. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rejmanová P., Kopecek J., Duncan R., Lloyd J. B. Stability in rat plasma and serum of lysosomally degradable oligopeptide sequences in N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide copolymers. Biomaterials. 1985 Jan;6(1):45–48. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(85)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper P. R., Drewinko B. Comparison of in vitro methods to determine drug-induced cell lethality. Cancer Res. 1976 Jul;36(7 Pt 1):2182–2188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokes Z. A., Rogers K. E., Rembaum A. Synthesis of adriamycin-coupled polyglutaraldehyde microspheres and evaluation of their cytostatic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):2026–2030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triton T. R., Yee G. The anticancer agent adriamycin can be actively cytotoxic without entering cells. Science. 1982 Jul 16;217(4556):248–250. doi: 10.1126/science.7089561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouet A. Isolation of modified liver lysosomes. Methods Enzymol. 1974;31:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(74)31034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouet A., Masquelier M., Baurain R., Deprez-De Campeneere D. A covalent linkage between daunorubicin and proteins that is stable in serum and reversible by lysosomal hydrolases, as required for a lysosomotropic drug-carrier conjugate: in vitro and in vivo studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Jan;79(2):626–629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenebergh A., Baurain R., Trouet A. Cellular pharmacokinetics of aclacinomycin A in cultured L1210 cells. Comparison with daunorubicin and doxorubicin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1982;8(2):243–249. doi: 10.1007/BF00255491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]