Summary:

The jumonji (jmj) gene plays important roles in multiple organ development in mouse, including cardiovascular development. Since JMJ is expressed widely during mouse development, it is essential that conditional knockout approaches be employed to ablate JMJ in a tissue-specific manner to identify the cell lineage specific roles of JMJ. In this report, we describe the establishment of a jmj conditional null allele in mice by generating a loxP-flanked (floxed) jmj allele, which allows the in vivo ablation of jmj via Cre recombinase-mediated deletion. Gene targeting was used to introduce loxP sites flanking exon 3 of the jmj allele to mouse embryonic stem cells. Our results indicate that the jmj floxed allele converts to a null allele in a heart-specific manner when embryos homozygous for the floxed jmj allele and carrying the α-myosin heavy chain promoter-Cre transgene were analyzed by Southern and Northern blot analyses. Therefore, this mouse line harboring the conditional jmj null allele will provide a valuable tool for deciphering the tissue and cell lineage specific roles of JMJ.

Keywords: Jumonji (Jarid 2), Cre-loxP technology, conditional knockout, mouse development, heart

The jumonji gene (jmj) was identified by gene trap technologies and shown to be a critical nuclear factor for mouse embryonic development [for review, see (Jung et al., 2005b)]. Jmj has been shown to play important roles in cardiovascular development (Lee et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 1999), the neural tube fusion process (Takeuchi et al., 1995), and hematopoiesis (Kitajima et al., 1999, 2001; Motoyama et al., 1997) in mouse embryos. JMJ has recently been renamed Jarid2 according to NCBI nomenclature but will be referred to in this report as JMJ. We have previously reported that knockout of jmj results in heart malformations, which mimic human congenital heart diseases. These malformations include ventricular septal defect, thin ventricular wall, and double outlet right ventricle (Lee et al., 2000). All mice having a homozygous jmj deletion (jmj-/-) die in the uterus (Takeuchi et al., 1995, 1999) or right after birth (Lee et al., 2000), depending on the genetic background of the mouse.

The amino acid sequence of JMJ reveals that JMJ belongs to the AT-rich interaction domain (ARID) transcription factor family (Gregory et al., 1996; Herrscher et al., 1995; Kortschak et al., 2000), and has been more recently described as a member of the JMJ transcription factor family (Balciunas and Ronne, 2000; Clissold and Ponting, 2001). Our structural/functional analyses of JMJ indicate that JMJ functions as a transcriptional repressor (Kim et al., 2003, 2004, 2005). JMJ inhibits ANF activation by Nkx2.5 and GATA4 via physical interaction (Kim et al., 2004). It has been demonstrated that JMJ is involved in regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation in a temporal- and spatial-dependent manner (Toyoda et al., 2003). At the molecular level, JMJ represses cardiomyocyte proliferation through interaction with the retinoblastoma protein (Jung et al., 2005a), which along with its relative p130 is one of the master cell cycle regulators for this lineage (MacLellan et al., 2005). Although the diverse functional roles of JMJ are emerging in association with embryonic development, the exact molecular roles of JMJ remain largely unknown.

The heart is the first organ to form and function during embryogenesis [for review, see (Olson and Schneider, 2003; Person et al., 2005)]. In early development, a population of cells within the anterior lateral plate mesoderm becomes committed to a cardiogenic fate. These cardiogenic cells migrate to form the cardiac crescent and then the linear heart tube. Subsequently, the rightward looping converts the heart tube from anterior-posterior into left-right patterning. A four-chambered heart is eventually formed upon the formation of septum and valves between them.

Many factors are implicated in the process of cardiac development based on their spatial and temporal expression patterns or their phenotypic effects when they are functionally inactivated. Transcriptional factors that play critical roles in early cardiac morphogenesis include the homeodomain protein Nkx2.5 (Lyons et al., 1995), the zinc-finger containing factor GATA4 (Kuo et al., 1997; Molkentin et al., 1997), the MADS-box containing factor MEF2C (Lin et al., 1997), and the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factors HAND 1 and 2 (Srivastava et al., 1995). Mice with null alleles of RXR (Sucov et al., 1994), RAR (Mendelsohn et al., 1994), TEF-1 (Chen et al., 1994), Fog2 (Tevosian et al., 2000), and CHF1/Hey2 (Sakata et al., 2002) display cardiac defects, including thin-walled myocardium, septal defects and/or abnormal outflow tract defects.

Gene knockout strategies applied to the whole body are largely inadequate to reveal underlying mechanisms of organ or tissue development, because of extraneous early lethality, confounding systemic defects, and inability to dissect with precision the interplay among diverse signals from distinct cell lineages that is required for organogenesis. To tackle the biological complexity of organ development, conditional gene knockout using the Cre-loxP system are often a more incisive model system (Chen et al., 1998; Chien, 2001; Gitler et al., 2004; Kwan, 2002). To unravel the logic of congenital heart disease and normal cardiac development, it is necessary to move beyond simply cataloging genes that are associated with heart defects. It is critical to examine the roles of JMJ in different cell lineages in the heart, which mainly consist of the myocardium, endocardium, epicardium, and cardiac neural crest. The complex interplay among these distinct lineages influences normal cardiac morphogenesis such as myocardium expansion in the ventricular wall, as well as appropriate cushion, outflow tract, and septal development.

In this study, we undertook the generation of a conditional jmj knockout mouse line by flanking the jmj exon 3 with loxP sites (flox). The genomic structure of mouse jmj and the precise exon/intron boundaries were determined based on the NCBI sequence data (see Fig. 1). Based on this information, we chose to flox exon 3 consisting of nucleic acids 238−373. Upon deletion of exon 3, splicing of exon 2 to exon 4 creates a frame shift that results in a termination codon at the beginning of exon 4, generating a truncated peptide of 15 amino acids of JMJ. Since JMJ consists of 1,234 amino acids, and the 15 amino acid peptide contains none of the known functional motifs of JMJ (Kim et al., 2003, 2004, 2005), it is likely that this peptide cannot function as a wild type JMJ, or a dominant-inhibitory protein, resulting in a null mutation. The targeting vector for jmj conditional knockout was constructed as described in the Materials and Methods section and depicted in Figure 2. The linearized targeting vector with Sal I was electroporated into murine strain 129/Sv embryonic stem (ES) cells (generously provided by Dr. Andras Nagy, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). ES cells that integrate the targeting vector either by homologous or random integration were selected by growth in the presence of G418 (333 μg/ml). 415 clones resistant to G418 were expanded and genomic DNAs were isolated from each clone. The ES cells that were correctly targeted by homologous recombination were identified by PCR and Southern blot analysis (data not shown). The four correctly targeted clones were transfected with the Cre encoding plasmid pBS185 (generously provided by Dr. Brian L. Sauer, Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Kansas City, MO) to delete artificial vector sequences such as pGK-neo and HSV-TK. After selection with ganciclovir (5 μm) as described elsewhere (Chen et al., 1998), 190 surviving colonies were screened by Southern and PCR analyses to identify the correct deletion type (Type II deletion in Fig. 2). 16 out of 190 clones were correctly deleted. Two correctly deleted ES clones that were determined to have normal karyotypes were injected into C57BL/C6 blastocysts to generate chimeras by the Transgenic Animal Facility at the University of Wisconsin. We successfully generated several highly chimeric male mice. These founder mice were bred to C57BL/C6 females to generate heterozygous (f/+ ) and homozygous jmj floxed mice (f/f), which are viable and appear normal (see Fig. 3).

FIG. 1.

A diagram of the mouse genomic structure of jumonji. There are 18 exons encoding jmj cDNA. Exon 2 encodes nucleic acids 34−237 bp, which includes the ATG translation initiation coding sequence. Exon 3 consists of 238−373 bp, which was floxed in this study for conditional deletions.

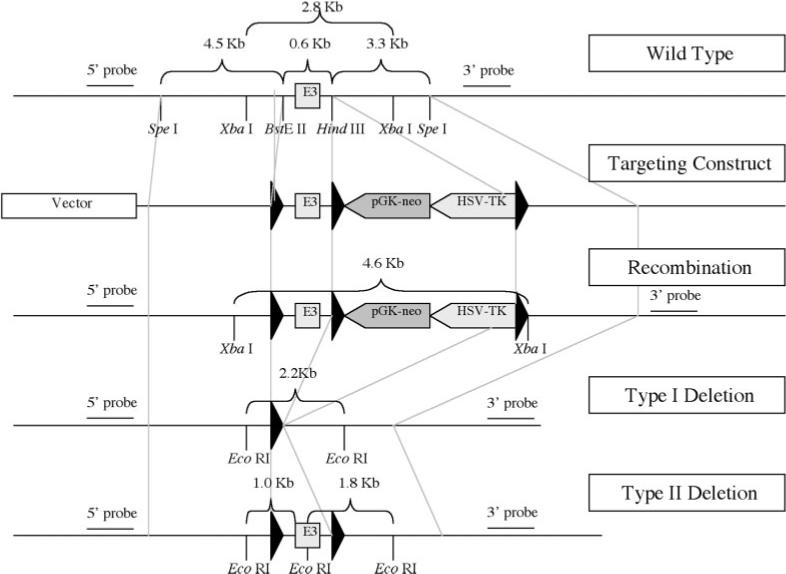

FIG. 2.

A diagram of the loxP targeting vector containing exon 3 (E3) and 5′ and 3′ adjacent fragments of jmj. This diagram depicts the restriction map of the mouse jmj locus, the targeting construct, the homologous recombinant allele, and the Type I and Type II deletions generated by transient transfection of the Cre expression plasmid into mouse ES cells. The Type II deletion in ES cells is the correct deletion type, which was subsequently used to generate the floxed jmj mice. Southern blot analyses were performed using 5′ and 3′ probes that are indicated in the diagram.

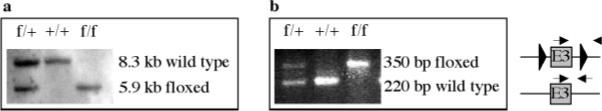

FIG. 3.

Genotyping of jmj floxed pups. a: Southern hybridization with DNAs isolated from tails. DNAs (20 μg/lane) were digested with Eco RV and the membrane was hybridized with 32P-labeled 3′ probe. +, wild type (8.3 kb band); f, floxed allele (5.9 kb band). The Southern blot analyses were also performed using 32P-labeled 5′ probe after digestion with Dra III, which showed a wild type (7 kb) or floxed allele (11 kb band) (data not shown). b: To genotype, PCR was also performed using a pair of primers located upstream and downstream of the 3′ loxP site using genomic DNAs isolated from tails. The arrows indicate the forward and reverse primers.

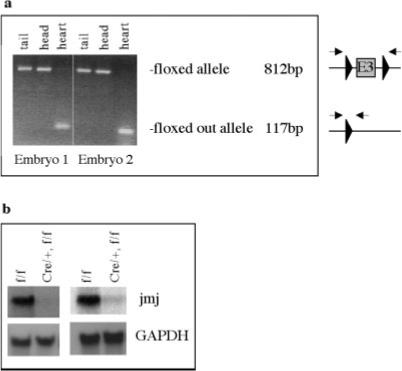

To determine whether the floxed jmj exon 3 can be deleted in vivo by the Cre recombinase in a heart-specific manner, jmj floxed mice were mated with α myosin heavy chain (αMHC)-Cre mice (Gaussin et al., 2002). The αMHC promoter is a strong cardiomyocyte-specific promoter, which has been widely used for the cardiac-specific expression of genes of interest in vivo. αMHC is expressed from the early embryonic heart at embryonic day (E) 7.5 to the adult heart in both atrium and ventricle (Lyons et al., 1990). The functional recombination of αMHC-Cre mice has been demonstrated as early as E9.5 and at E11.5 when mated to ROSA26 Cre-dependent lacZ-reporter embryos (Gaussin et al., 2002). Therefore, αMHC-Cre mice are appropriate for myocardial-specific deletion of jmj. Our PCR data on genomic DNA showed that exon 3 was efficiently deleted in the heart, but not in the head or tail of αMHC conditional knockout mouse embryos at E14 (αMHC-Cre+/-, jmj f/f) (Fig. 4a). More importantly, the Cre-loxP function was also validated by Northern blot analyses using a probe designed to detect exon 3. The jmj transcripts in the hearts of αMHC Cre/+, jmj f/f embryos were not detectable with a normal over-night exposure time (Fig. 4b), indicating an efficient deletion of jmj. A low level of jmj expression was detected with a prolonged exposure time (3 days), which is likely due to the expression of jmj in non-cardiomyocytes including cardiac fibroblasts in the heart. The expression level of jmj is much higher in cardiomyocytes than cardiac fibroblasts in the mouse embryonic heart (Jung et al., 2005a). Initial characterization of αMHC-Cre/+, jmj f/f mice shows no change in Mendelian ratio at postnatal day 21. However, more extensive studies are required to determine the phenotypes of these mice. These results clearly demonstrate that CreloxP functions very well in our conditional jmj knockout mice. Therefore, the jmj floxed mice described in this article will provide a valuable tool to determine the tissue-specific roles of jmj in embryonic development as well as in adult tissues. Further, these mice will serve to advance our understanding of the transcriptional control of normal organ development.

FIG. 4.

Confirmation of a jmj deletion in conditional knockout mice (αMHC Cre/+, jmj f/f mice). a: Genomic deletion of the jmj exon by αMHC Cre. PCR was performed using a pair of primers located just outside two loxP sites with DNAs from various tissues of two E14 embryos as indicated. The arrows indicate the forward and reverse primers. b: The level of jmj transcript in two conditional knockout embryos by MHC-Cre was analyzed by Northern blot analyses. The total RNA extracted from the heart of E14 embryos (20 μg/lane) was hybridized by 32P-labeled exon 3 probe. GAPDH is a loading control. Lanes 1, and 3, f/f; lanes 2 and 4, jmj conditional knockout (Cre/+, f/f).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the Targeting Vector

Four P1 jmj genomic clones were obtained using a probe containing the sequence 3′ to the transcriptional initiation site of jmj, designated as intron 2 (a service provided by Genome Systems; St. Louis, MO). All four genomic clones were greater than 100 kb, and contained the jmj sequence that was used to screen a mouse P1 genomic library. Genomic sequence of the fragment of interest was identical to the published sequence of NIH BAC clone containing jmj contigs (NIH BAC clone RP23−257b17 from genomic sequence library). We constructed the targeting vector as described in Figure 2. A 9-kb genomic region containing exon 3 and the flanking region was subcloned into the pBluescript vector using SpeI restriction enzyme site. Three fragments consisting of a 0.6-kb fragment containing exon 3, a 4.5-kb fragment containing 5′, and a 3.3-kb containing 3′ region of exon 3 were obtained by restriction enzyme digestion of the 9-kb/pBluescript vector. These three fragments were sequentially subcloned into the pflox vector containing three loxP sites flanking the pGK-neo and HSV-TK cassettes (Chen et al., 1998) (provided by Drs. Ju Chen and Jamey Marth at University of California San Diego, CA). The exon 3 region (a BsteII-HindIII fragment) was first subcloned into the vector that was digested with BamHI to generate the pflox-exon 3 plasmid. The region 3′ to exon 3 (a HindIII-SpeI fragment) was subcloned into the XbaI digested pflox-exon 3 vector. The region homologous to the 5′ region (a SpeI-BsteII fragment) was then subcloned into the XhoI site, completing the targeting vector. The integrity of the targeting vector sequence was confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing. To confirm the ability of Cre recombinase to act on the loxP sites, the targeting vector was incubated with purified Cre recombinase (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendation, which was transformed into competent bacteria. DNA was prepared from individual colonies to analyze the pattern of recombination and we confirmed that loxP sequences in our targeting vector were functional (data not shown).

Genotyping of Mice and Mouse Embryos

To determine if the mice were homozygous or heterozygous for the floxed allele, primers were designed that would overlap exon 3 containing the loxP sites (Fig. 3b). These primers were forward 5′-GCG GTA AAT GGT GAG TTG AAA G-3′, and reverse 5′-ACA GAC TGA CAC ACC TTC C-3′. PCR amplification of DNA from mice homozygous for the loxP sites produced a 350-bp band, mice heterozygous for the floxed allele produced both the 350-bp and the 220-bp bands, and those containing no loxP sites (wild type allele) produced only a 220-bp band.

To determine whether the jmj loxP allele is deleted in vivo in a tissue-specific manner, jmj conditional knockout mice (αMHC-Cre/+, f/f) were generated. First, αMHC-Cre mice (Gaussin et al., 2002) were crossed with jmj f/f to generate αMHC Cre/+, f/+ mice that were subsequently mated with jmj f/f to generate αMHC-Cre/+ , f/f mice. DNAs extracted from various embryonic tissues at E14 were subjected to PCR to confirm the deletion of exon 3 (Fig. 4a). The primers used were forward 5′-GTA CCC GGG GAT CAA TTC GA-3′ and reverse 5′-AAG CTC TAG AGG ATC AGC TTG-3′. PCR primers to detect Cre were forward 5′-GGT CGC AAG AAC CTG ATG GAC A-3′, and reverse 5′-CTA GAG CCT GTT TTG CAC GTT C-3′.

Northern and Southern blot analyses were performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2000).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We greatly appreciate Timothy Ridolfi for his excellent technical support in construction of the targeting vector. We also thank the Transgenic Animal Facility staff at the University of Wisconsin's Biotechnology Center for their help in the generation of the chimera mice. Our sincere thanks go to Dr. Ju Chen (University of California, San Diego, San Diego, CA) for helpful discussions and providing valuable plasmids.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health, Contract grant number: HL67050, Contract grant sponsor: American Heart Association, Contract grant number: 0030002N.

Footnotes

†This article is a US Government work and, as such, is in the public domain in the United States of America.

LITERATURE CITED

- Balciunas D, Ronne H. Evidence of domain swapping within the jumonji family of transcription factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:274–276. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01593-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Friedrich GA, Soriano P. Transcriptional enhancer factor 1 disruption by a retroviral gene trap leads to heart defects and embryonic lethality in mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2293–2301. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kubalak SW, Chien KR. Ventricular muscle-restricted targeting of the RXRalpha gene reveals a non-cell-autonomous requirement in cardiac chamber morphogenesis. Development. 1998;125:1943–1949. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.10.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien KR. To Cre or not to Cre: The next generation of mouse models of human cardiac diseases. Circ Res. 2001;88:546–549. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.6.546. comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clissold PM, Ponting CP. JmjC: Cupin metalloenzyme-like domains in jumonji, hairless and phospholipase A2β. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:7–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussin V, Van de Putte T, Mishina Y, Hanks MC, Zwijsen A, Huylebroeck D, Behringer RR, Schneider MD. Endocardial cushion and myocardial defects after cardiac myocyte-specific conditional deletion of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor ALK3. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2878–2883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042390499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler AD, Kong Y, Choi JK, Zhu Y, Pear WS, Epstein JA. Tie2-Cre-induced inactivation of a conditional mutant Nf1 allele in mouse results in a myeloproliferative disorder that models juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:581–584. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000113462.98851.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory SL, Kortschak RD, Kalionis B, Saint R. Characterization of the dead ringer gene identifies a novel, highly conserved family of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:792–799. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrscher RF, Kaplan MH, Lelsz DL, Das C, Scheuermann R, Tucker PW. The immunoglobulin heavy-chain matrix-associating regions are bound by Bright: A B cell-specific trans-activator that describes a new DNA-binding protein family. Genes Dev. 1995;9:3067–3082. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.24.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Kim TG, Lyons GE, Kim HR, Lee Y. Jumonji regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation via interaction with retinoblastoma protein. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:30916–30923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J, Mysliwiec MR, Lee Y. Roles of JUMONJI in mouse embryonic development. Dev Dyn. 2005b;232:21–32. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TG, Chen J, Sadoshima J, Lee Y. Jumonji represses atrial natriuretic factor gene expression by inhibiting transcriptional activities of cardiac transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:10151–10160. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10151-10160.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TG, Jung J, Mysliwiec MR, Kang S, Lee Y. Jumonji represses α-cardiac myosin heavy chain expression via inhibiting MEF2 activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TG, Kraus JC, Chen J, Lee Y. JUMONJI, a critical factor for cardiac development, functions as a transcriptional repressor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42247–42255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima K, Kojima M, Kondo S, Takeuchi T. A role of jumonji gene in proliferation but not differentiation of megakaryocyte lineage cells. Exp Hematol. 2001;29:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00686-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitajima K, Kojima M, Nakajima K, Kondo S, Hara T, Miyajima A, Takeuchi T. Definitive but not primitive hematopoiesis is impaired in jumonji mutant mice. Blood. 1999;93:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortschak RD, Tucker PW, Saint R. ARID proteins come in from the desert. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:294–299. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CT, Morrisey EE, Anandappa R, Sigrist K, Lu MM, Parmacek MS, Soudais C, Leiden JM. GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1048–1060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KM. Conditional alleles in mice: Practical considerations for tissue-specific knockouts. Genesis. 2002;32:49–62. doi: 10.1002/gene.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Song AJ, Baker R, Micales B, Conway SJ, Lyons GE. Jumonji, a nuclear protein that is necessary for normal heart development. Circ Res. 2000;86:932–938. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.9.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Q, Schwarz J, Bucana C, Olson EN. Control of mouse cardiac morphogenesis and myogenesis by transcription factor MEF2C. Science. 1997;276:1404–1407. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons GE, Schiaffino S, Sassoon D, Barton P, Buckingham M. Developmental regulation of myosin gene expression in mouse cardiac muscle. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2427–2436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons I, Parsons LM, Hartley L, Li R, Andrews JE, Robb L, Harvey RP. Myogenic and morphogenetic defects in the heart tubes of murine embryos lacking the homeo box gene Nkx2–5. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1654–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan WR, Garcia A, Oh H, Frenkel P, Jordan MC, Roos KP, Schneider MD. Overlapping roles of pocket proteins in the myocardium are unmasked by germ line deletion of p130 plus heart-specific deletion of Rb. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2486–2497. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2486-2497.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn C, Lohnes D, Decimo D, Lufkin T, LeMeur M, Chambon P, Mark M. Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development (II). Multiple abnormalities at various stages of organogenesis in RAR double mutants. Development. 1994;120:2749–2771. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Lin Q, Duncan SA, Olson EN. Requirement of the transcription factor GATA4 for heart tube formation and ventral morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1061–1072. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motoyama J, Kitajima K, Kojima M, Kondo S, Takeuchi T. Organogenesis of the liver, thymus and spleen is affected in jumonji mutant mice. Mech Dev. 1997;66:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: Development redux in disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Person AD, Klewer SE, Runyan RB. Cell biology of cardiac cushion development. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:287–335. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y, Kamei CN, Nakagami H, Bronson R, Liao JK, Chin MT. Ventricular septal defect and cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the transcription factor CHF1/Hey2. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16197–16202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252648999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava D, Cserjesi P, Olson EN. A subclass of bHLH proteins required for cardiac morphogenesis. Science. 1995;270:1995–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucov HM, Dyson E, Gumeringer CL, Price J, Chien KR, Evans RM. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1007–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T, Kojima M, Nakajima K, Kondo S. Jumonji gene is essential for the neurulation and cardiac development of mouse embryos with a C3H/He background. Mech Dev. 1999;86:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi T, Yamazaki Y, Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Kondo S, Motoyama J, Higashinakagawa T. Gene trap capture of a novel mouse gene, jumonji, required for neural tube formation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1211–1222. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tevosian SG, Deconinck AE, Tanaka M, Schinke M, Litovsky SH, Izumo S, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. FOG-2, a cofactor for GATA transcription factors, is essential for heart morphogenesis and development of coronary vessels from epicardium. Cell. 2000;101:729–739. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80885-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda M, Shirato H, Nakajima K, Kojima M, Takahashi M, Kubota M, Suzuki-Migishima R, Motegi Y, Yokoyama M, Takeuchi T. Jumonji downregulates cardiac cell proliferation by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Dev Cell. 2003;5:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]