One can readily agree with Bernice Elger and Arthur Caplan's conclusion in their Viewpoint on ‘Consent and anonymization in research involving biobanks' that “[t]o maximize the benefit of biobanks and genetic databases for both research and public health, a single ethical framework is essential, which requires a harmonization of the terminology about anonymity” (Elger & Caplan, 2006). However, one has to disagree with their statement that “[i]f samples contain any trace of DNA, they are not truly anonymous, because it is always possible to identify the donor through DNA fingerprinting.”

According to Webster's Dictionary (1991 edition), ‘to identify' means ‘to establish the identity', and ‘identity' means ‘who a person is'. The latter term is generally accepted to comprise at least a name, as well as date and place of birth. DNA fingerprinting can only determine with a certain probability—depending on the quality of the material and the sensitivity of the method—that a biological sample originates from a specific individual. It does not lead to identification per se, because DNA itself does not contain such identity data. Therefore, finding a match between two DNA fingerprints is not the same as finding out the identity of an individual.

Various scenarios can be defined with regard to DNA fingerprinting. First, if the sample is registered without identity data—or without a key that connects the sample to identity data—and if there is no clue from whom the sample originates, such a sample is de facto anonymous. To find the donor of the sample would require comparing the DNA fingerprint of the sample with the DNA fingerprints of all the people on the planet, which is possible in theory but impossible in practice.

Second, there could be indicators suggesting that an anonymous sample originated from a person in a limited group of individuals with known identity. Such a situation occurs, for example, in forensics, when a DNA fingerprint from a crime scene sample is compared with the DNA fingerprints of a group of suspects. The group of suspects cannot be too large because of financial, logistical and time constraints. One should be aware that if a DNA fingerprint match is established, the sample is not used to identify the subject. However, as a consequence of the matching the sample is no longer anonymous.

Third, the donor identifies him/herself to a biobank, which is storing anonymous samples, and provides a second sample for comparison. Through matching DNA fingerprints, even an anonymous sample and the research and diagnostic data retrieved from it can be linked to the donor. Of course, this situation requires that the donor knows where his/her sample is kept and that there are no constraints to prevent the DNA fingerprinting of each sample in the biobank. Again, the sample is no longer anonymous after the fingerprint matching, but it was not used to identify the donor. Furthermore, if the donor came to the biobank anonymously, it would be possible to perform DNA fingerprinting and at the same time guarantee that the sample remains anonymous.

Fourth, a sample is registered together with identity data—or with a code and key to connect the sample to the identity data—and there are a limited number of individuals with unknown identity from whom the sample might originate. Such a situation occurred when blood samples from the Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden) were used to identify Swedish victims of the tsunami disaster in December 2004 (News in Brief, 2005).

Finally, if the identity of the individual from whom the sample originates is known, identification through a match between the DNA fingerprint of the sample and the individual is a self-evidently unnecessary exercise.

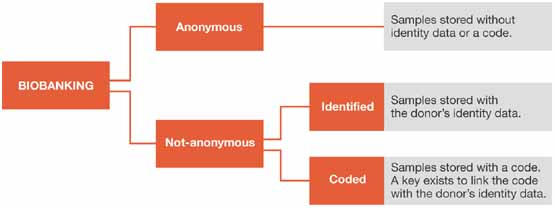

To clarify the ambiguity surrounding anonymity, the international use of a simple scheme (Fig 1) could bring clarity, uniformity and the required harmonization of terminology.

Figure 1.

Biobanking terminology

References

- Elger BS, Caplan AL (2006) Consent and anonymization in research involving biobanks. EMBO Rep 7: 661–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- News in Brief (2005) Swedish biobank data used to identify tsunami victims. Nature 433: 564 [Google Scholar]