Abstract

Background

The Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis, launched following World Health Assembly Resolution 50.29 (WHA 50.29), has been facilitated in its progress by new research findings, drug donations, the availability of diagnostic tools, disability management strategies to help those already suffering and the development of partnerships. The strategy recommended by the World Health Organization of annual treatment with a two-drug combination has proved safe.

Discussion

Using different approaches in several countries the elimination of lymphatic filariasis (LF) has been demonstrated to be feasible during earlier decades. These successes have been largely overlooked. However, the programme progress since 2000 has been remarkable – upscaling rapidly from 2 million treatments in 2000 to approximately 60 million in 2002. Around 34 countries had active programmes at the end of 2002. It is anticipated that there will be further expansion – but this will be dependent on additional resources becoming available. The programme also provides significant opportunities for other disease control programmes to deliver public health benefits on a large scale. Few public health programmes have upscaled so rapidly and so cost-effectively (<$0.03/treatment in some Asian settings) – one country treating 9–10 million people in a day (Sri Lanka). The LF programme is arguably the most effective pro-poor public health programme currently operating which is based on country commitment and partnerships supported by a global programme and alliance. Tables are provided to summarize programme characteristics, the benefits of LF elimination, opportunities for integration with other programmes and relevance to the Millennium Development Goals.

Summary

Lymphatic filariasis elimination is an "easy-to-do" inexpensive health intervention that provides considerable "beyond filariasis" benefits, exemplifies partnership and is easily evaluated. The success in global health action documented in this paper requires and deserves further support to bring to fruition elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem and health benefits to poor people. A future free of lymphatic filariasis will reduce poverty and bring better health to poor people, prevent disability, strengthen health systems and build partnerships.

Background

The Global Programme for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis (GPELF) was established in early 2000. This followed World Health Assembly Resolution 50.29 (WHA 50.29) in 1997 calling on the member states of the World Health Organisation (WHO) to eliminate the disease as a public health problem. This landmark resolution followed the 1993 declaration by the International Task Force for Disease Eradication (ITFDE) that lymphatic filariasis (see Table 1) was one of the six eliminable diseases [1].

Table 1.

Lymphatic Filariasis

| • Caused by thread-like parasitic worms (Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi and Brugia timori) that damage the human lymphatic system – transmitted by mosquitoes (see additional file 1) |

| • One of the most disabling and disfiguring of diseases |

| • 80+ endemic countries (Figure 1) |

| • 1+ billion people are at risk of infection |

| • 120 million people are infected. Of these... |

| • 43 million people have swelling of the limbs and breasts (known as lymphoedema) and genitals (known as hydrocoele), and their more chronic state – known as elephantiasis – in which the skin becomes enormously thickened, and is rough, hard, and fissured |

| • It is a disease of poverty – affecting the "poorest of the poor" – preventing those afflicted from living a normal working and social life (See additional file 2) |

| • Children acquire the disease early and are blighted for life |

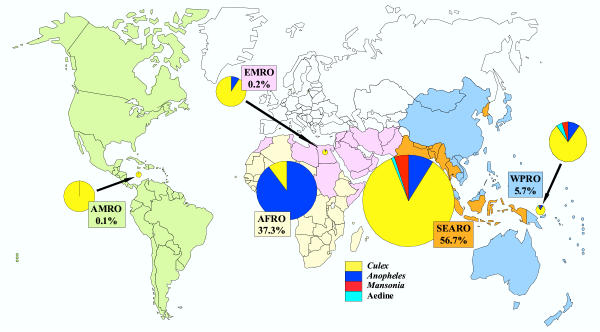

Figure 1.

The proportions of the total, global burden posed by lymphatic filariasis that occur in the areas covered by the World Health Organization's regional offices for the Americas (AMRO), Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO), Africa (AFRO), South-east Asia (SEARO) and the Western Pacific (WPRO). Burden was estimated as the number of disability-adjusted life-years (DALY) lost and is shown split, in the pie chart for each region, according to the type of mosquito responsible for transmitting the causative parasite. Reprinted with permission from Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Vol. 96, Supplement No. 2, S3–S13 (2002).

Intensive research over the last decade has shown the efficacy of new drug combinations [2], created simple diagnostic tools [3] (See additional file 3), improved knowledge of pathology [4,5] (See additional file 4) and demonstrated that those with existing disability could have symptoms of lymphoedema and elephantiasis alleviated by community home-based care [6].

The WHA resolution also prompted two major pharmaceutical donors to provide free donations of albendazole globally (GlaxoSmithKline) and Mectizan® (ivermectin) (Merck and Co. Inc.), for countries where lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis (river blindness) are co-endemic, for as long as needed (Table 2) [7,8]. These pledges represent the largest long-term donation to a global health care initiative and a commitment to provide quality drugs to stop transmission of a disease. However, both companies recognize that the provision of drugs alone is not enough to sustain programme activity and provide wider support to the programme.

Table 2.

Lymphatic Filariasis as a unique and successful programme

| • Two drugs (largely donated or inexpensive) once per year for time limited duration |

| • DEC + albendazole in areas where onchocerciasis is not endemic |

| • Albendazole + Mectizan® where onchocerciasis is co-endemic with lymphatic filariasis |

| • Two major pharmaceutical companies involved |

| • A global disease (80 endemic countries; 1+ billion at risk) but regionalised programmatically |

| • Many synergistic/integration opportunities in the programme (See Table 4) |

| • Major successes already demonstrated |

| • Disability alleviation and prevention component to increase coverage and compliance via household and community self help |

| • Mass drug distribution – an overtly pro-poor intervention |

| • Intervention provides entry point to both rural and urban health settings |

| • Different drug distribution systems dependent on country decisions |

| • Separation of programmatic and GAELF responsibilities |

| • A free non-restrictive alliance with diverse partners |

| • Strong involvement of academic institutions and research funders |

| • Wide use of IT for dissemination and communication |

Discussion

The development of a new strategy – time limited (at least 5 years) – annual co-administration of two drugs and the creation of GPELF and the Global Alliance for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis (GAELF) builds on successful lymphatic filariasis elimination programmes in several countries [7-9]. These countries in different endemic areas and epidemiological settings have convincingly demonstrated that transmission could be stopped permanently. China, Japan, Korea, Thailand and the Solomon Islands using different strategies have eliminated transmission; Sri Lanka has eliminated Brugian filariasis and smaller foci in Brazil, Malaysia, Costa Rica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago have been eliminated [10].

The establishment of a diverse partnership in 2000 to form GAELF and the endorsement of the WHO strategic plan created a momentum that has resulted in 34 countries establishing active programmes. The programme has expanded rapidly with the number of people treated annually rising from 2.9 million in 12 countries in 2000 to 28.89 million in 2001 and an estimated 60 million in 34 countries in 2002 [11]. This upscaling occurred as the safety and tolerability of the drug combinations was confirmed on an increasingly large scale, as the extent of the disease and its consequent disabling effects on poor people were recognised, and as the magnitude of the latent burden in children was appreciated at the same time that new diagnostic tests revealed that children acquire infection at an early age [12] (One study from Haiti found that by the age four more than 25% of children were already infected [13]). These findings were recognised by many endemic countries who considered that LF was a priority as a disease that could be eliminated as public health problem, thus improving productivity and well-being of affected communities through reducing costs to individuals, communities and under-resourced health systems and enhancing earning capacity through increased productivity in various sectors.

It has also become increasingly apparent that the two-drug intervention provides substantial collateral health benefits to afflicted communities and provides additional intervention platforms for health systems. The multiplicities of health benefits that derive from annual treatment are depicted in Table 3, whilst the opportunity for integration and synergy with other health programmes are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

The benefits of Lymphatic Filariasis elimination

| • Lymphatic Filariasis transmission stopped |

| • Intestinal helminth burden reduced |

| • Anaemia caused by hookworm alleviated |

| • Disability alleviated and skin diseases controlled |

| • Nutritional status improved |

| • Health systems strengthened |

| • Improved surveillance, monitoring and evaluation |

| • Enhanced drug distribution system |

| • Social mobilisation approaches improved |

| • Linkage of LF to other disease interventions |

| • Increased human resource capacity in health |

| • Strengthened knowledge of disease distribution |

| • Reduced costs to poor families who seek inappropriate treatment |

| • Reduced costs of surgery at district level |

| • Increased school attendance |

| • A bridge to other public-private partnerships |

Table 4.

Opportunities for integration and synergy with other programmes

| • Vector control via bednets with malaria control |

| • Vector control of dengue vectors |

| • Intestinal helminths/Schistosomiasis programmes via schools |

| • Addition of DEC to iodinated/fluoridated salt (with the possibility of fortification with other micronutrients) |

| • Onchocerciasis control linkage in Africa where onchocerciasis/LF are co-endemic |

| • Linkage to guinea-worm programme for surveillance and drug distribution |

| • Use of National Immunisation Days for annual treatment |

| • Evaluation and rapid appraisal systems can link to other diseases e.g. anaemia and malaria, vector status, Loa loa, schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis |

| • Linkages to Vitamin A and Zithromax (Trachoma) distribution programmes |

Lymphatic filariasis is one of the "neglected diseases"; however its elimination appears not only feasible if programmes are sustained over a 5-year time scale but the programme has unique characteristics which enable it to appeal to a wide constituency of donors (Tables 2 and 5). Lymphatic filariasis elimination can viably contribute to the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (Table 5) and represents an, as yet, unheralded global health success story; early targets for expansion of the programme's treatment numbers have been achieved. Countries have become convinced of the benefits of the programme, an active non-restrictive alliance of committed partners has been created, and real progress in arresting transmission has been reported from countries which commenced treatment in 2000 and which have completed three or four rounds of mass drug administration (MDA) – Egypt, Samoa, Vanuatu, Tanzania and Zanzibar. All are recording significant declines in prevalence and intensity of microfilariaemia. Furthermore, those suffering from the disease also appear to benefit from the treatment itself – an unpredicted outcome – as the frequency of filarial fevers are markedly reduced, and more recently a study from Papua New Guinea has shown a decrease in the incidence of hydrocoele (swelling of the scrotal sac) following annual mass treatment over 4 years [14] (although the effects on leg lymphoedema are equivocal [15]). The momentum of this success must be sustained to bring hope to the 1+ billion people at risk and remove LF as an impediment to the productivity and well-being of poor people and free future generations from exclusion, stigma, dependency and pain [16].

Table 5.

Lymphatic Filariasis elimination and the Millennium Development Goals

| Goal 1 |

| • Eliminate extreme poverty and hunger |

| • LF is a disease of poor people in poor countries, particularly in individuals earning below $1/day. LF elimination reduces health care costs and increases productivity |

| • Reduces prevalence of underweight children by improving nutritional status, micronutrient uptake enhanced through albendazole and by improvement of agricultural productivity and improving household/community food security |

| Goal 2 |

| • Achieve universal primary education |

| • LF elimination will increase capacity of poor families to access education through increased income, reduced caring for afflicted parents, increased school attendance and performance via drug treatment impact on intestinal helminths |

| • Schools can act as an entry point for drug distribution, increasing both coverage and parental awareness of the benefits |

| Goal 3 |

| • Promote gender equity and empowerment |

| • Women play a role as drug distributors enhancing respect and empowerment |

| • Women's marital prospects enhanced as LF control reduces stigma of disease |

| Goal 4 and Goal 5 |

| • Reduce child mortality and reduce maternal mortality |

| • Women's health status improves as albendazole alleviates hookworm anaemia |

| • Anaemia → better birth outcomes → reduced prevalence of low birth weight babies hence reduced maternal and infant mortality |

| Goal 6 |

| • Combat HIV/AIDS/malaria and other diseases |

| • LF and malaria control interlinked by bednets, alleviation of anaemia by albendazole; drug distribution can enhance bednet coverage and re-impregnation rates |

| • Albendazole impacts on child and maternal mortality via alleviation of anaemia burden |

| Goal 7 and Goal 8 |

| • Ensure environmental sustainability |

| • Develop a Global partnership for Development |

| • GAELF and GPELF are an effective diverse global partnership committed to elimination of a disease of poverty by 2020. |

| • Elimination has been achieved in several countries bringing development benefits to poor communities |

Summary

Lymphatic filariasis elimination is an "easy-to-do" inexpensive health intervention that provides considerable "beyond filariasis" benefits (Tables 4 and 5), exemplifies partnership and is easily evaluated. The success in global health action documented here requires and deserves further support to bring to fruition elimination of lymphatic filariasis as a public health problem and health benefits to poor people. A future free of lymphatic filariasis will reduce poverty and bring better health to poor people, prevent disability, strengthen health systems and build partnerships.

If the international health community cannot deliver two safe efficacious drugs annually – which are largely free – which in addition to stopping transmission of lymphatic filariasis also bring profound additional health benefits, it is difficult to expect more complex interventions to succeed in controlling other infectious diseases.

The Global Alliance for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis has the skills, commitment and partnerships to succeed, thereby preventing the next generation of children being infected and subsequently afflicted by this most stigmatising of diseases. There is, however, a need for significant new resources to be committed to achieve this goal.

Related websites

Global Alliance for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis

GlaxoSmithKline: Lymphatic Filariasis Programme

http://www.gsk.com/filariasis/

Mectizan® Donation Program

http://mectizan.org/lymphatic_filariasis.asp

filariasis.net

Competing Interests

David H Molyneux is a member of the Secretariat of the Global Alliance for the Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis.

Authors' Contributions

David H Molyneux was sole author.

Supplementary Material

Wuchereria bancrofti is the causative parasite responsible for approximately 90% of all cases of lymphatic filariasis. This animation illustrates the parasite's life cycle. Copyright © filariasis.net

"The Patient's Perspective" This video – filmed in Brazil, Haiti, India, Samoa and Tanzania – gives a unique insight into how lymphatic filariasis affects individuals and prevents them from leading a normal life.

• T1 connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_t1.rm (7.3 MB);

• ISDN connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_isdn.rm (1.6 MB);

• Modem connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_modem.rm (1.2 MB). We would like to thank GlaxoSmithKline, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NEPAF, NGO Amaury Coutinho (Recife, Brazil) and all the people who took part in this video. This video was produced by Lipfriend Rodd International and supported by an education grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

The ICT (Immunochromatographic Card Test) procedure for lymphatic filariasis is a simple, rapid test for detecting adult worm antigen in human blood and permits the rapid assessment of prevalence, facilitates mapping of disease distribution and evaluation of levels of transmission in populations under mass drug administration. This animation illustrates the ICT procedure. We would like to thank The Wellcome Trust for making this animation available to us. Copyright © The Wellcome Trust

Our understanding of the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of hydrocoele (one of the sequelae of lymphatic filariasis where fluid collects in the scrotal sac causing it to swell) has been greatly increased by ultrasonography which is able to detect adult Wuchereria bancrofti worms in scrotal lymphatic vessels on account of the characteristic pattern of adult worm movements, known as the filarial dance sign. Examination by ultrasound is a non-invasive tool that has become important in clinical studies of lymphatic filariasis. In this digital video sequence (a transverse ultrasound scan of the left testis) an enlarged lymphatic vessel can be seen (arrow), along with one or more adult worms – detectable by their typical movements – the filarial dance sign. We would like to thank Sabine Mand and Achim Hoerauf for making this video available to us. Reproduced with permission from Filaria Journal 2003, 2:3 (27 February 2003) Copyright © Sabine Mand and Achim Hoerauf, Bernhard Nocht Institute, Hamburg, Germany.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his appreciation to the following organizations for their financial support: the UK Department for International Development http://www.dfid.gov.uk/, GlaxoSmithKline http://www.gsk.com/filariasis/ and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation http://www.gatesfoundation.org/; and to the following colleagues for their comments and suggestions on this manuscript: Dr Francecso Rio (Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination, WHO), Dr Brian Bagnall (Global Community Partnerships, GlaxoSmithKline), Dr David Addiss and Dr Pat Lammie (Division of Parasitic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), Dr Bernhard Liese (World Bank) and Mr Michael Brown and Mrs Joan Fahy (Lymphatic Filariasis Support Centre, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine).

References

- Recommendations of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MM, Jayakody RL, Weil GJ, Nirmalan N, Jayasinghe KS, Abeyewickrema W, Rezvi Sheriff MH, Rajaratnam HN, Amarasekera N, de Silva DC, Michalski ML, Dissanaike AS. Efficacy of single dose combinations of albendazole, ivermectin and diethylcarbamazine for the treatment of bancroftian filariasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:94–97. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil GJ, Lammie PJ, Weiss N. The ICT Filariasis Test: A Rapid-format Antigen Test for Diagnosis of Bancroftian Filariasis. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:401–404. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral F, Dreyer G, Figueredo-Silva J, Noroes J, Cavalcanti A, Samico SC, Santos A, Coutinho A. Live adult worms detected by ultrasonography in human Bancroftian filariasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:753–757. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mand S, Marfo-Debrekyei Y, Dittrich M, Fischer K, Adjei O, Hoerauf A. Animated documentation of the filaria dance sign (FDS) in bancroftian filariasis. Filaria J. 2003;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer G, Addiss D, Dreyer P, Norões J. Basic Lymphoedema Management. Treatment and prevention of problems associated with lymphatic filariasis. 1. New Hampshire, Hollis; 2002. p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux DH, Neira M, Liese B, Heymann D. Lymphatic filariasis: setting the scene for elimination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:589–591. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottesen EA, Duke BO, Karam M, Behbehani K. Strategies and tools for the control/elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75:491–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux DH, Zagaria N. Lymphatic filariasis elimination: progress in global programme development. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96 Suppl 2:S15–40. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MJ, Njongmeta LH, Addiss D, Ngwira B, Fiack C, Ottesen EA, Bassanez M, Molyneux DH. Review of historical data of lymphatic filariasis control programmes - Evidence that lymphatic filariasis can be eliminated as a public health problem. Filaria J. 2003;In press [Google Scholar]

- Lymphatic filariasis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt C, Ottesen EA. Lymphatic filariasis: an infection of childhood. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:582–606. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammie PJ, Reiss MD, Dimock KA, Streit TG, Roberts JM, Eberhard ML. Longitudinal analysis of the development of filarial infection and antifilarial immunity in a cohort of Haitian children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:217–221. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockarie MJ, Tisch DJ, Kastens W, Alexander ND, Dimber Z, Bockarie F, Ibam E, Alpers MP, Kazura JW. Mass treatment to eliminate filariasis in Papua New Guinea. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1841–1848. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addiss DG. Mass treatment of filariasis in New Guinea. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1179–81; author reply 1179-81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200303203481219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez Tan JZ. The Elimination of Lymphatic Filariasis: A Strategy for Poverty Alleviation and Sustainable Development - Perspectives from the Philippines. Filaria J. 2003;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2883-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Wuchereria bancrofti is the causative parasite responsible for approximately 90% of all cases of lymphatic filariasis. This animation illustrates the parasite's life cycle. Copyright © filariasis.net

"The Patient's Perspective" This video – filmed in Brazil, Haiti, India, Samoa and Tanzania – gives a unique insight into how lymphatic filariasis affects individuals and prevents them from leading a normal life.

• T1 connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_t1.rm (7.3 MB);

• ISDN connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_isdn.rm (1.6 MB);

• Modem connection rtsp://gskdotcomrm.fplive.net/gskdotcom/lf_modem.rm (1.2 MB). We would like to thank GlaxoSmithKline, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NEPAF, NGO Amaury Coutinho (Recife, Brazil) and all the people who took part in this video. This video was produced by Lipfriend Rodd International and supported by an education grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

The ICT (Immunochromatographic Card Test) procedure for lymphatic filariasis is a simple, rapid test for detecting adult worm antigen in human blood and permits the rapid assessment of prevalence, facilitates mapping of disease distribution and evaluation of levels of transmission in populations under mass drug administration. This animation illustrates the ICT procedure. We would like to thank The Wellcome Trust for making this animation available to us. Copyright © The Wellcome Trust

Our understanding of the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of hydrocoele (one of the sequelae of lymphatic filariasis where fluid collects in the scrotal sac causing it to swell) has been greatly increased by ultrasonography which is able to detect adult Wuchereria bancrofti worms in scrotal lymphatic vessels on account of the characteristic pattern of adult worm movements, known as the filarial dance sign. Examination by ultrasound is a non-invasive tool that has become important in clinical studies of lymphatic filariasis. In this digital video sequence (a transverse ultrasound scan of the left testis) an enlarged lymphatic vessel can be seen (arrow), along with one or more adult worms – detectable by their typical movements – the filarial dance sign. We would like to thank Sabine Mand and Achim Hoerauf for making this video available to us. Reproduced with permission from Filaria Journal 2003, 2:3 (27 February 2003) Copyright © Sabine Mand and Achim Hoerauf, Bernhard Nocht Institute, Hamburg, Germany.