Abstract

The pathways between a receptor and transcriptional activation mediated by NF-κB are complex. The study of human gene mutations that result in dysregulation of these pathways has provided insight into the functions of individual components of the pathway, their interrelations, and the significance of these systems to the organism .

Inducible activation of gene transcription

NF-κB was recognized as a DNA-binding factor that exists in the cytoplasm of resting cells and that accumulates in the nucleus under appropriate conditions (1). The ability of NF-κB to shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus in a tightly regulated manner led to the exploration of a complex series of events leading to activation-induced gene expression, and to the discovery of factors that prevent the transit of NF-κB into the nucleus (2). Receptor-mediated NF-κB activation of gene transcription and its stringent control are fundamental to cell development, survival, and function. In this issue of the JCI, Courtois and colleagues report a novel human mutation in a protein that negatively regulates NF-κB activation (3). The resultant mutant dominantly inhibits the activation of NF-κB (see below) and gives rise to a clinical syndrome of ectodermal dysplasia (ED) and susceptibility to infection.

NF-κB activity is imparted by a protein dimer selected from five mammalian homologues: p50, p52, p65 (RelA), Rel, and RelB (p50 and p52 are derived from larger precursors, p105 and p100, respectively). The majority of dimers formed by these individual NF-κB members are capable of activating transcription by binding to κB sites in DNA. The dimerization of these molecules occurs through a conserved N-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD). Importantly, the RHD also serves as the binding site for one of several inhibitors of NF-κB (IκBs). An IκB can physically interfere with NF-κB dimerization or block nuclear localization sequences within the NF-κB member. The family of molecules possessing these activities consists of at least seven members: IκBα, IκBβ, IκBε, IκBγ, Bcl-3, and inhibitory domains of the p105 and p100 precursor proteins. The cytoplasmic association of an IκB and a NF-κB member is controlled by the phosphorylation of the IκB, which leads to its ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation (Figure 1). The release of an NF-κB protein from IκB allows it to participate in dimer formation, translocate to the nucleus, and activate transcription. The phosphorylation of IκB, therefore, is a critical regulatory step in NF-κB function.

Figure 1.

Receptor-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation and inhibition by a dominant negative IκB. A variety of cell surface receptors are capable of inducing associated specific signaling complexes that can activate the IKK signalosome to phosphorylate IκB. This phosphorylation of IκB leads to its proteosomal degradation, thus liberating NF-κB dimers and allowing them to regulate gene transcription in the nucleus. The particular signaling complex activated and utilized by a given cell surface receptor varies and is specific to the receptor family. When a mutant IκB is present, the IKK signalosome is unable to phosphorylate the key serine residues, and NF-κB is retained in the cytoplasm bound to the mutant protein despite appropriate upstream activation. The octagons represent NF-κB family members, and individual dimers are frequently heterogeneous. NKR, NK cell activation receptor; TCR, T cell receptor; BCR, B cell receptor.

NF-κB activation

Phosphorylation of IκB is mediated by an IκB kinase (IKK), a large, multisubunit signaling complex (signalosome) capable of binding IκB as well as other upstream regulators. The classical IKK signalosome consists of two catalytic subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, and a regulatory subunit, IKKγ, also known as the NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) (4). IKKα is capable of functioning independently of the aforementioned IKK signalosome and has the particular capacity to induce processing of p100 to yield p52 (5). When appropriately activated by phosphorylation, IKK serves as a conduit to the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and is the bottleneck common to many activation pathways (Figure 1).

Genetic disorders resulting from mutations in the NF-κB activation pathway

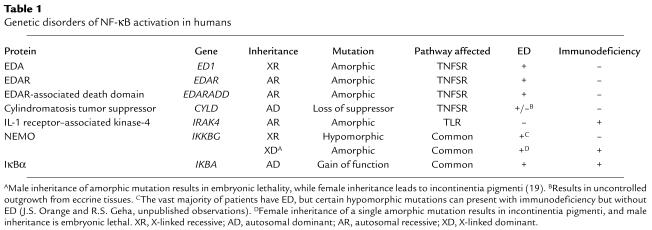

Unique insight into the role of NF-κB receptor–mediated function has been gained through the study of congenital diseases that affect NF-κB (Table 1). Investigation of diseases that affect development of the ectoderm have provided evidence for an essential role for NF-κB in this process. ED is characterized by fine, sparse hair, conical teeth, and hypohidrosis and has been linked to gene mutations that interfere with the appropriate ligation of the TNF superfamily receptor (TNFSR) ectodysplasin-A receptor (EDAR) or with appropriate EDAR signaling. Mutations can affect the EDAR receptor itself (6), its ligand ectodysplasin-A (EDA) (7, 8), or its associated adaptor protein (EDAR-associated death domain) (9). These mutations result in an inability to activate NF-κB through the EDAR system during developmental stages critical to ectodermal maturation, resulting in ED. Although these genetic lesions are not associated with immunodeficiency, a subset of patients with ED have variable, but often profound, immunodeficiency. The majority of individuals with ED and immunodeficiency have a hypomorphic X-linked recessive mutation in the gene encoding the NEMO protein (10–13). In addition to impaired EDAR signaling, cells from these boys fail to demonstrate significant nuclear translocation of NF-κB after exposure to TNF or the Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4) ligand LPS. As a result, these individuals have a remarkable susceptibility to disease caused by pyogenic bacteria and mycobacteria.

Table 1.

Genetic disorders of NF-κB activation in humans

In this issue of the JCI, Courtois and colleagues describe a child with a point mutation in one allele of IκBα that results in the inability of the mutant IκBα to be phosphorylated (3) (Figure 1). Substitution (S32I) of one of two key serine residues (S32 and S36) that are targets for IKK phosphorylation and are critical for phospho-IκBα ubiquitination and degradation results in a dominant gain-of-function inhibitor of NF-κB. Like boys with a NEMO mutation, the patient had ED as well as combined immunodeficiency characterized by an inability to respond to ligands for TLR and TNFSR, impairment of antibody production and T cell proliferation, and susceptibility to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Unlike many patients with the NEMO mutation (13), he had normal NK cell activity and did not have mycobacterial infection.

Links to upstream receptors

Much of the diversity attributed to NF-κB functions can be ascribed to specific cell surface receptors that recognize a variety of unrelated ligands. The pathways that link these diverse ligands and families of receptors to activation of IKK are complex. Key receptor families that can activate NF-κB and induce gene transcription include TLRs, TNFSRs, T and B cell receptors, and NK cell activation receptors. Each of these different groups of receptors activates IKK by utilizing a specific cascade of signaling molecules (with some degree of overlap) that forms a receptor-specific signaling complex. These multifaceted complexes present numerous opportunities for specific activation and regulation. Gene mutations that affect NEMO or IκBα will presumably affect all receptors that converge upon IKK. Mutations of proteins functioning in the complex between specific receptors and IKK, however, have also been described (Table 1). They include the cylindromatosis tumor suppressor (CLYD), which negatively regulates TNFSR signaling (14–17), and the IL-1 receptor–associated kinase-4 (IRAK-4), which participates in activation mediated by TLRs (18). Restricted phenotypes resulting from these different mutations, e.g., cutaneous tumors in CLYD mutation and susceptibility to infection in IRAK-4 deficiency, illustrate the function of the mutant proteins and their upstream receptors.

Lessons learned

The discovery of NF-κB activation disorders is providing great insight into the complex events involved in receptor-mediated NF-κB–dependent transcriptional activation. Clinical presentations that include ectodermal abnormalities and/or immunodeficiency should prompt evaluation of NF-κB function and may lead to the appreciation of novel mutations in members of the IKK signalosome and related proteins that affect the function of specific receptors that utilize NF-κB. These discoveries could provide novel targets for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by dysregulated NF-κB activation.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 1108.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: ectodermal dysplasia (ED); inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB); IκB kinase (IKK); NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO); TNF superfamily receptor (TNFSR); ectodysplasin-A (EDA); EDA receptor (EDAR); Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4).

References

- 1.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. Activation of DNA-binding activity in an apparently cytoplasmic precursor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Cell. 1988;53:211–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90382-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl.):S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Courtois G, et al. A hypermorphic IκBα mutation is associated with autosomal dominant anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia and T cell immunodeficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1108–1115. doi:10.1172/JCI200318714. doi: 10.1172/JCI18714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Israel A. The IKK complex: an integrator of all signals that activate NF-kappaB? Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:129–133. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01729-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dejardin E, et al. The lymphotoxin-beta receptor induces different patterns of gene expression via two NF-kappaB pathways. Immunity. 2002;17:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00423-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monreal AW, et al. Mutations in the human homologue of mouse dl cause autosomal recessive and dominant hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:366–369. doi: 10.1038/11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kere J, et al. X-linked anhidrotic (hypohidrotic) ectodermal dysplasia is caused by mutation in a novel transmembrane protein. Nat. Genet. 1996;13:409–416. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider P, et al. Mutations leading to X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia affect three major functional domains in the tumor necrosis factor family member ectodysplasin-A. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18819–18827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Headon DJ, et al. Gene defect in ectodermal dysplasia implicates a death domain adapter in development. Nature. 2001;414:913–916. doi: 10.1038/414913a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doffinger R, et al. X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-kappaB signaling. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:277–285. doi: 10.1038/85837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain A, et al. Specific missense mutations in NEMO result in hyper-IgM syndrome with hypohydrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:223–228. doi: 10.1038/85277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zonana J, et al. A novel X-linked disorder of immune deficiency and hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is allelic to incontinentia pigmenti and due to mutations in IKK-gamma (NEMO) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:1555–1562. doi: 10.1086/316914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orange JS, et al. Deficient natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with IKK-γ/NEMO mutations. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;109:1501–1509. doi:10.1172/JCI200214858. doi: 10.1172/JCI14858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bignell GR, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:160–165. doi: 10.1038/76006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brummelkamp TR, Nijman SM, Dirac AM, Bernards R. Loss of the cylindromatosis tumour suppressor inhibits apoptosis by activating NF-kappaB. Nature. 2003;424:797–801. doi: 10.1038/nature01811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trompouki E, et al. CYLD is a deubiquitinating enzyme that negatively regulates NF-kappaB activation by TNFR family members. Nature. 2003;424:793–796. doi: 10.1038/nature01803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovalenko A, et al. The tumour suppressor CYLD negatively regulates NF-kappaB signalling by deubiquitination. Nature. 2003;424:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature01802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picard C, et al. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with IRAK-4 deficiency. Science. 2003;299:2076–2079. doi: 10.1126/science.1081902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smahi A, et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature. 2000;405:466–472. doi: 10.1038/35013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]