Abstract

Deficiencies in the pathway of N-glycan biosynthesis lead to severe multisystem diseases, known as congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG). The clinical appearance of CDG is variable, and different types can be distinguished according to the gene that is altered. In this report, we describe the molecular basis of a novel type of the disease in three unrelated patients diagnosed with CDG-I. Serum transferrin was hypoglycosylated and patients’ fibroblasts accumulated incomplete lipid-linked oligosaccharide precursors for N-linked protein glycosylation. Transfer of incomplete oligosaccharides to protein was detected. Sequence analysis of the Lec35/MPDU1 gene, known to be involved in the use of dolichylphosphomannose and dolichylphosphoglucose, revealed mutations in all three patients. Retroviral-based expression of the normal Lec35 cDNA in primary fibroblasts of patients restored normal lipid-linked oligosaccharide biosynthesis. We concluded that mutations in the Lec35/MPDU1 gene cause CDG. This novel type was termed CDG-If.

Introduction

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a family of severe inherited diseases caused by a defect in protein N-glycosylation (1–4). These multisystem disorders present with a wide variety of clinical features, such as disorders of the nervous system development, psychomotor retardation, dysmorphic features, hypotonia, coagulation disorders, and immunodeficiency. The broad spectrum of features reflects the critical role of N-glycoproteins during embryonic development, differentiation, and maintenance of cell functions (5, 6).

Isoelectric focusing of serum transferrin, a sialylated glycoprotein, is used as a diagnostic tool and makes it possible to distinguish two basic types of CDG: deficiencies in assembly of the core oligosaccharide or its transfer to protein are referred to as CDG-I and defects in trimming and modification of the core oligosaccharide after its transfer to protein are referred to as CDG-II (7). Several subtypes of CDG have been characterized at the biochemical and genetic level, such as the deficiency in phosphomannomutase activity, caused by a defect in the PMM2 gene (CDG-Ia) (8, 9), the deficiency in the phosphomannose isomerase activity due to a mutated PMI locus (CDG-Ib) (10, 11), mutations in the ALG6 gene resulting in a reduced dolichylphosphoglucose-dependent (Dol-P-Glc–dependent) α1,3-glucosyltransferase activity (CDG-Ic) (12–15), mutations in the ALG3 gene leading to a reduced dolichylphosphomannose-dependent (Dol-P-Man–dependent) α1,3-mannosyltransferase activity (CDG-Id) (16), and a defect in the Dol-P-Man synthase activity due to mutations in the DPM1 gene (CDG-Ie) (17, 18). Furthermore, a deficiency in the Golgi enzyme N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase II leads to CDG-IIa (19), mutations in the glucosidase I gene lead to CDG-IIb (20), and an impaired transport of GDP-fucose into the Golgi apparatus causes CDG-Iic (21).

The assembly of the dolichylpyrophosphate-linked oligosaccharide core is a highly conserved process that takes place at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (22). The synthesis of the lipid-linked Man5GlcNAc2 intermediate occurs at the cytoplasmic face of the ER, and nucleotide-activated sugars serve as donors for the glycosyltransferases involved in this process. The oligosaccharide assembly is completed at the luminal leaflet of the ER membrane. The lipid-linked Man5GlcNAc2 intermediate, and Dol-P-Man as well as Dol-P-Glc, the substrates of the luminal glycosyltransferase reactions, are translocated across the membrane in the so-called flipping processes (23). The complete oligosaccharide is the preferred substrate for the enzyme complex oligosaccharyltransferase (OTase), which transfers the oligosaccharide from the lipid carrier to selected asparagine residues of nascent polypeptide chains (24–26). However, the OTase will also transfer biosynthetic intermediates, albeit with a reduced efficiency (25). The terminal α-1,2 glucose residue of the lipid-linked Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide is an essential element in substrate recognition by the OTase complex (27). The incomplete but glucosylated Glc3Man5GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide is transferred to protein more efficiently than Man5GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide (28).

In this study, we present the identification of a novel type of CDG (CDG-If) found in three unrelated patients. When lipid-linked oligosaccharide (LLO) intermediates isolated from these patients were analyzed, we detected the accumulation of dolichylpyrophosphate-linked Man5GlcNAc2, Glc3Man5GlcNAc2, Man9GlcNAc2, and Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 LLOs. Sequencing of the Lec35 gene, recently termed MPDU1 (29), from patients’ fibroblasts revealed mutations in this locus known to be required for efficient use of Dol-P-Man and Dol-P-Glc in mammalian cells (29). Importantly, the deficiency in the LLO biosynthesis in patients’ fibroblasts was complemented by the expression of normal Lec35 cDNA. Our data define a novel type of CDG (CDG-If) caused by a defective Lec35 function.

Methods

Cell culture of patient cells.

Primary fibroblasts isolated from a skin biopsy were grown in DMEM/F12 with high glucose levels (Life Technologies Inc., Paisley, Scotland), supplemented with 10% FCS. Epstein-Barr virus-transformed (EBV-transformed) lymphoblasts (30) were grown in Iscove’s modified DMEM with 10% FCS.

Analysis of serum transferrin.

Isolectric focusing was done as previously described (31).

Analysis of LLO.

Fibroblasts were grown on 530-cm2 plates to 90% confluence, washed with PBS, and preincubated in DMEM (Life Technologies Inc.) supplemented with 5% dialyzed FCS at 37°C for 90 minutes. Cells were then labeled in 80 ml of the same medium for 1 hour at 37°C by the addition of 175 μCi [3H]mannose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). To terminate the labeling, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS twice and scraped from the plate in 10 ml methanol/0.1 mM Tris, pH 7.4 (8:3 vol/vol). Then 10.9 ml chloroform was added, the samples were vigorously mixed, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,300 g for 5 minutes. LLOs were extracted (12) and analyzed by HPLC as described (32). To obtain standard oligosaccharide, exponentially growing yeast cells were labeled for a short time period in order to obtain labeled biosynthetic intermediates. LLOs were extracted as described (12). However, the relative abundance of the different intermediates varied between different preparations.

For quantification of the relative abundance of the different oligosaccharide species, the radioactivity in a peak area was determined and compared to the sum of the radioactivity representing all LLO species. No correction was made for the relative abundance of mannose.

PNGaseF treatment of cellular protein and analysis of protein-linked oligosaccharide.

Cells were grown and labeled as described for the analysis of LLOs. The cells were scraped from the plates in 2 ml methanol/0.1 mM Tris, pH 7.4 (8:3 vol/vol). After the addition of 5 ml chloroform and mixing, the samples were centrifuged at 5,000 g for 5 minutes. The interphase was carefully removed and LLOs were separated from proteins by extraction into chloroform/methanol/water (10:10:3 vol/vol/vol). After centrifugation, the resulting pellet containing the glycoproteins was dried under a stream of nitrogen to remove chloroform. Proteins were denatured by the addition of 200 μl of 1% SDS/2% 2-mercaptoethanol and incubation on ice for 30 minutes. Oligosaccharides were cleaved from protein by adding 500,000 U/ml PNGaseF (New England Biolabs Inc., Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) in 30 μl of 0.5 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 60 μl 10% Nonidet-P40 and incubating overnight at 30°C. Proteins were removed from oligosaccharides by precipitating them with 600 μl ethanol. Then, the samples were dried under a stream of nitrogen and resuspended in 60 μl of water. Before HPLC analysis (see above), samples were filtered through an Ultrafree MC filter (Durapore; Millipore Corp., Bedford, Massachusetts, USA).

Analysis of total dolichol-P levels.

Dolichol-P (Dol-P) was extracted as described (33). EBV-immortalized cells were grown to an approximate cell number of 109. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 6 ml H2O. Dolichyl-18-P (6 μg) in a small volume of hexane was added as an internal standard. The cell suspension was then subjected to strong alkaline hydrolysis (3 M KOH in 40% methanol, 100°C, 60 minutes). Dol-P was extracted by the addition of 6 ml methanol and 24 ml dichloromethane to the hydrolysate, and the mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 40°C. The organic (lower) phase was removed and washed four times with equal volumes of dichloro-methane/methanol/water (3:48:47). The washed organic phase was dried under N2, and the lipids were dissolved in 10 ml methanol/water (98:2) containing 20 mM H3PO4. A C-18 Sep-Pak (2 ml) was equilibrated with 10 ml methanol/water (98:2) containing 20 mM H3PO4, and the lipid extract was applied to the column. The column was washed with 10 ml methanol/water (98:2) containing 20 mM H3PO4 and then with 10 ml methanol/water (98:2). Dolichol and Dol-P were eluted with chloroform/methanol (2:1), and the eluate was adjusted to 0.5% NH4OH (vol/vol). A silica Sep-Pak (2 ml) was equilibrated with 40 ml chloroform/methanol (2:1) containing 0.5% NH4OH, and the dolichol- and Dol-P–containing sample was applied to the column. Dolichol was removed from the silica Sep-Pak in 20 ml chloroform/methanol (2:1) containing 0.5% NH4OH, and Dol-P was eluted with 30 ml chloroform/methanol/water (10:10:3). Samples were dried under N2 and resuspended in the mobile phase solvent mixture. The Dol-P fraction was separated into single isoprenologues on a Merck LiChrospher (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). 100 reverse-phase C-18 column (5 μm, 4 × 12.5 mm) equilibrated with the mobile phase for 1 hour using a Merck/Hitachi L-6200A Intelligent pump (Merck KGaA). The mobile phase (isopropanol/methanol/water, 65:30:5, containing 20 mM H3PO4) was run at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Samples were injected using an autosampling device (Merck/Hitachi AS-2000A). Dol-P was detected by absorption at 214 nm with a Merck/Hitachi L-4250 UV-VIS detector.

Genomic PCR and sequence analysis.

The genomic structure of the human Lec35/MPDU1 gene was deduced by searching GenBank using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) algorithm with the human Lec35 cDNA, and exon and intron boundaries were determined. The regions containing the exons 1 to 7 were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA and the following primers: 5′-ACG AAA GTC AAT GGC GGT CTG-3′ and 5′-CGT CAC TTA GTC GCC GAT CAA G-3′ for exon 1; 5′-CTG GCC TGG GTT TCA GAC ATC-3′ and 5′-CCA CTT TGC TGC CTT GTA ACC TC-3′ for exons 2 and 3; and 5′-CAG AGC ATA GTG TCC CTG GAT GG-3′ and 5′-GAG GAT GAG TAA GTC ACA CCA GCA G-3′ for exons 4 through 7. Conditions for the amplification protocol are available upon request. PCR fragments of the expected size of 238 bp for exon 1, 487 bp for exons 2 and 3, and 1,048 bp for exons 4 through 7 were purified, and sequences were determined as described previously (17).

Expression of Lec35 cDNA in primary human fibroblasts.

An expression cassette including the Lec35 cDNA flanked by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and the SV40 polyA signal derived from the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA) was subcloned into the pBABE-hygro retroviral shuttle vector (34). Amphotropic recombinant retrovirus was generated by Lipofectamine-mediated (Invitrogen Corp.) transfection of the packaging CAK8 cell line with 5 μg of the respective retrovirus DNA constructs (35). The culture medium of transfected cells was recovered after 48 hours and used as retrovirus suspension. Human primary fibroblasts were infected at a moi of 10 in the presence of polybrene at 4 μg/ml for 5 hours. Hygromycin B (20 μg/ml) selection was started 48 hours after infection.

Results

Identification of the patients.

The primary clinical and laboratory data of the three unrelated patients are listed in Table 1. In summary, patient S had intractable seizures from birth. He had severe feeding difficulties necessitating nasogastric feeding. Psychomotor development was absent. He showed persistent oxygen dependency from the age of 4 months, and developed ascites progressing to anasarca during the last months of his life. There was no hypoalbuminemia and no evidence of cardiac or pulmonary pathology. He developed patchy desquamation over his entire body. His seizure activity worsened, and this was accompanied by recurrent apnea leading to his death at the age of 10 months. Patient L was admitted to hospital at the age of 5 months for attacks of hypertonia, a congenital disabling ichthyosis-like skin disorder and psychomotor retardation. Because of low serum cholesterol, a tentative diagnosis of hypo-β lipoproteinemia was made. Skin biopsy showed nonspecific changes. She was seen again at 2 years and 4 months with the same symptoms and, in addition, growth retardation. She was next seen at the age of 16 years. She had severe dwarfism, psychomotor retardation (developmental level of 1 year), and unchanged skin disease. Laboratory investigation showed a normal growth hormone response. Serum transferrin isoelectro focusing revealed increased disialotransferrin, suggesting a diagnosis of CDG (Figure 1a). Patient A is a boy with severe psychomotor retardation but no growth or skin problems. At 15 months he had generalized seizures that responded well to valproate. At the age of 10 years his psychomotor developmental age is about 2.5 years.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory data of the three patients

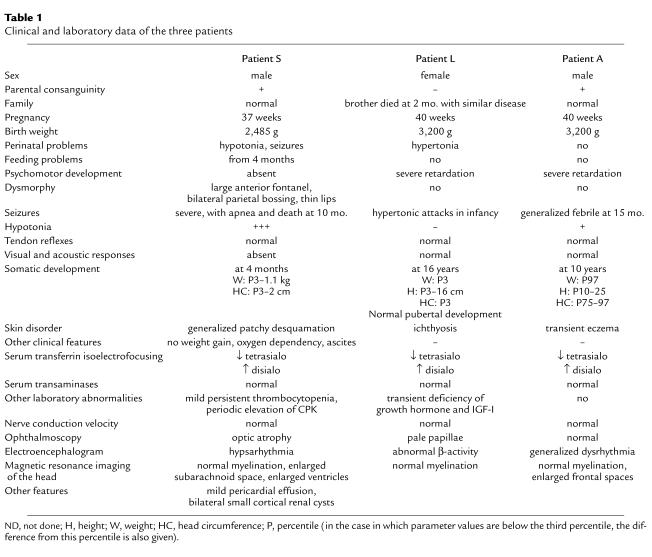

Figure 1.

(a) Isoelectric focusing of serum transferrin. Data from two different experiments are shown. The number of negative charges (sialic acid residues) is given at the left. Transferrin from healthy control individuals (lanes 1 and 5), from CDG-1a patients (lanes 2 and 7), from patient L (lane 3), patient A (lane 4), and patient S (lane 6) was analyzed. (b–d) Analysis of LLOs in CDG patients, control subjects, and yeast cells. Metabolically labeled LLOs were isolated from wild-type yeast cells (standard), ALG3-deficient yeast cells overexpressing the ALG6 locus (Δalg3 + pALG6), and fibroblasts derived from patient S (b), patient A (c), and patient L (d). [3H]oligosaccharides were released by mild acid hydrolysis and analyzed by HPLC. Elution was monitored by a radiodetector. The elution positions of Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 (G3M9), Man9GlcNAc2 (M9), Man8GlcNAc2 (M8), Man5GlcNAc2 (M5), and Glc3Man5GlcNAc2 (G3M5) are indicated.

The isoelectric focusing of serum transferrin from the three patients revealed hypoglycosylation of the protein in a type 1–like pattern (36) (Figure 1a). Phosphomannomutase and phosphomannose isomerase activities in patients’ fibroblasts were found to be normal, excluding CDG-Ia and CDG-Ib (data not shown).

Accumulation of intermediates in LLO biosynthesis in patients’ fibroblasts.

Based on the isoelectric-focusing pattern of serum transferrin (Figure 1a), we concluded that there was a defect in oligosaccharide core assembly or in its transfer to protein in these patients. Therefore, we analyzed the LLO isolated from patients’ fibroblasts. A specifically altered LLO profile can be diagnostic for a given type of CDG-I. Figure 1, b–d, shows the LLO profiles obtained upon HPLC analysis. All three patients accumulated the lipid-linked Man5GlcNAc2 intermediate as well as a detectable amount of completely assembled oligosaccharide (Glc3Man9GlcNAc2). Preparations of oligosaccharides derived from patient S and patient A revealed Man9GlcNAc2, and an additional oligosaccharide species was detected in fibroblasts from patient S. Comigration experiments using LLO from a genetically tailored yeast mutant strain (relevant genotype: Δalg3 overexpressing ALG6; ref. 37) suggested that this species represented a Glc3Man5GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide, lacking all four mannose residues derived from Dol-P-Man–dependent mannosyltransferase reactions. This type of LLO profile has not been observed in previously characterized types of CDG. We concluded that the biosynthesis of the LLO was affected in this novel type of CDG.

Incompletely assembled oligosaccharides are transferred to protein in patients’ fibroblasts.

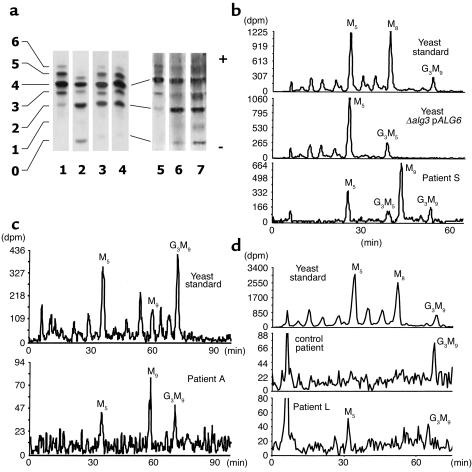

To analyze N-linked oligosaccharides (NLO), glycoproteins in patient and control fibroblasts were labeled by incubating cells in the presence of [3H]mannose. Total glycoprotein was isolated, the oligosaccharide moiety was cleaved from protein with PNGase F and extracted and analyzed by HPLC (Figure 2). In all cells, we detected a major peak comigrating with the Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide standard and minor peaks comigrating with Glc1Man9GlcNAc2, Man8GlcNAc2, and Man7GlcNAc2 oligosaccharides. Analysis of NLO from cells that were grown in the presence of deoxynojirimycin as glycosidase inhibitor supported the assignment of these peaks and suggested that complete Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 was transferred to protein in all patients’ fibroblasts (data not shown). These different oligosaccharide species can be explained by the action of deglucosylating enzymes (38) and ER-localized mannosidases (39) as well as UDP-glucose–dependent glucosyltransferase (40) on the complete Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide transferred to protein. Interestingly, we observed a novel group of protein-bound oligosaccharides in patients L and S. A putative Man5GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide represented the major peak, but signals comigrating with the Man4GlcNAc2 and the Man6GlcNAc2 were also present. Experiments using deoxynojirimycin inhibitor are compatible with the hypothesis that these N-linked oligosaccharides derived from the transfer of Glc3Man5GlcNAc2 to protein (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Analysis of NLOs in CDG patients and a control subject. Metabolically labeled NLOs were isolated from a healthy individual (control subject) and from patients A, L, and S (CDG-If patient A, CDG-If patient L, CDG-If patient S). [3H]-labeled NLOs were cleaved from protein by incubation with PNGaseF, protein was removed by precipitation, and the liberated oligosaccharides were analyzed by HPLC using a radiodetector to monitor elution positions. Elution positions for standard oligosaccharide intermediates Man3GlcNAc2 to Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 (M3, M4, M5, M6, M7, M8, M9, G1M9) are given at the top of the figure.

Normal Dol-P levels in patients’ fibroblasts.

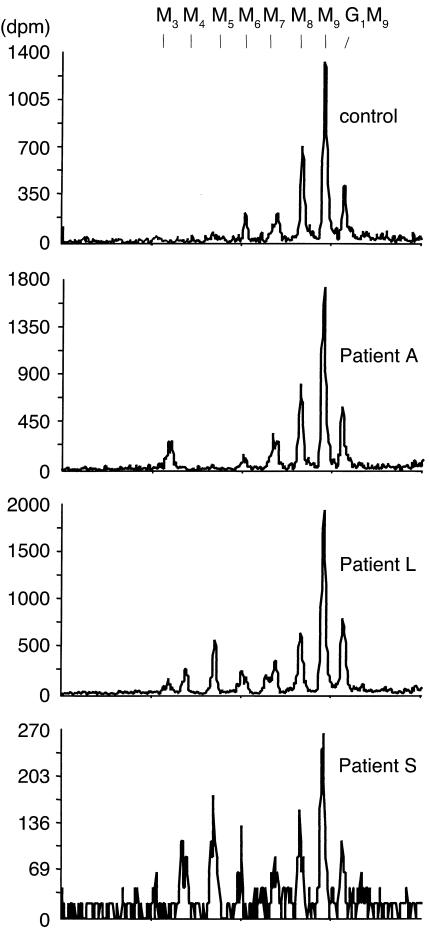

Mutations that affect the synthesis of the lipid carrier Dol-P can severely affect the N-glycosylation pathway (41, 42). Therefore, Dol-P was analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively in immortalized lymphoblasts from patient L and from a control subject. These lymphoblasts exhibited the same LLO pattern as the primary fibroblasts derived from the same patient (data not shown). Human dolichol and dolichylphosphate has a chain length of 17–21 isoprene units (43) (Figure 3). Dol-P standards isolated from yeast cells served as a marker for the chain length of the Dol-P, and Dol-P composed of 18 isoprene units (Dol-18-P) was added as an internal standard before extraction. As shown in Figure 3, patient L contains very similar levels of Dol-P as compared with the control subject, and the chain-length distribution also is the same in patient L and in the control subject. From this we concluded that biosynthesis of Dol-P was not affected.

Figure 3.

Analysis of total Dol-P levels in a healthy individual (control subject) and patient L. Dol-P was extracted from approximately 109 EBV-transfected lymphoblasts grown in liquid culture and analyzed. Isoprenologues were separated by HPLC and detected using an ultraviolet detector at 214 nm. Dol-P composed of 18 isoprene units (Dol-18-P) was added to the cells before extraction and served as a qualitative and quantitative marker. Dol-Ps isolated from genetically tailored yeast cells served as standards for the Dol-Ps composed of 15–21 isoprene units (Dol-P standards). The chain length of the isoprenologues is indicated above the peaks.

Mutations in the LEC35/MPDU1 locus of patients’ cells.

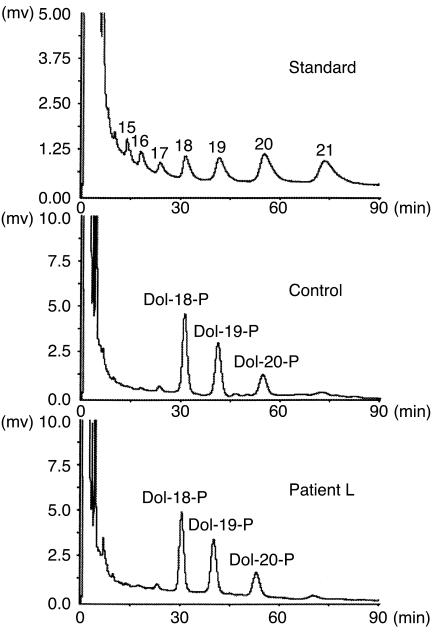

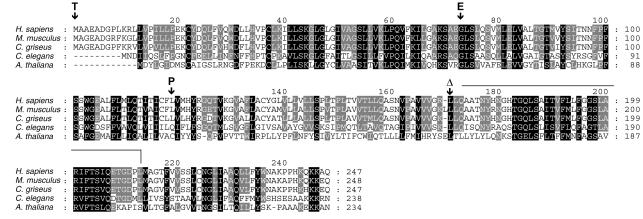

The deficiencies in both N-linked glycosylation and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor biosynthesis (data not shown) but normal Dol-P levels in patients’ fibroblasts suggested a deficiency in Dol-P-Man synthesis or use. However, the presence of significant levels of lipid-linked Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide (in patient S and A) also suggested a deficiency in Dol-P-Glc use. Such a phenotype, not known in mutant yeast cells, was reminiscent of deficiencies detected in Chinese hamster ovary–derived (CHO-derived) Lec35 mutant cells (29). Therefore, the seven exons of the Lec35/MPDU1 locus were amplified from patient-derived genomic DNA, and their sequence was determined. Indeed, in all three patients mutations were found (Figure 4). Patient A is homozygous for a T→C substitution at position 356 (cDNA-ORF), leading to an amino acid change (L119P), and patient S is homozygous for a G→A substitution at position 218 (G73E). Patient L was heterozygous for two different mutations in the Lec35/MPDU1 locus, the parental origin of these two mutations was determined by sequencing parental Lec35/MPDU1 loci. A 2T→C substitution changing the initiating methionine to threonine (M1T) was of maternal origin, and a deletion of a C at position 511 (511delC) leading to a frameshift was the paternal allele. We postulated that the mutations in the Lec35/MPDU1 gene of the patients are the cause for the CDG phenotype observed. This is supported by the observation that the deduced Lec35 protein sequence from five control individuals and from 46 assembled EST sequences available in the databases do not contain polymorphisms.

Figure 4.

Alignment of the primary sequence of Lec35 proteins from human (Homo sapiens, GenBank accession no. XP_008236), mouse (Mus musculus, accession number Q9R0Q9), hamster (Cricetulus griseus, accession no. Q60441), worm (Caenorhabditis elegans, accession no. AAA83473), and plant (Arabidopsis thaliana, assembled from genomic clone AF147262). Regions conserved in the five proteins are shaded in black, and residues that are conserved in four proteins are shaded in gray. The amino acid substitutions and the change of reading frame detected in CDG-If patients are indicated above the human sequence. The line following the Δ-mark for the mutation 511delC shows the portion of the polypeptide translated in another reading frame before a stop codon appears (vertical line).

Complementation of the Lec35/MPDU1 mutation in primary patients’ fibroblasts.

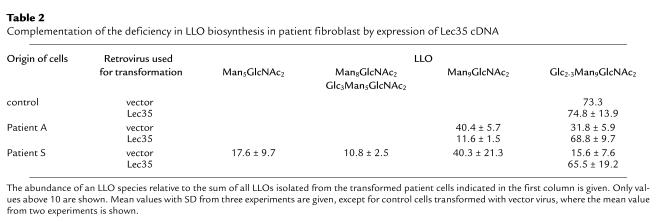

To demonstrate the direct relation between the Lec35 deficiency and the glycosylation disorder, a Lec35 expression cassette was introduced (the CMV promoter was used to drive Lec35 cDNA expression) into the primary patients’ fibroblasts using a retroviral vector. A retroviral vector expressing a hygromycin B resistance gene alone was used as a negative control in these experiments. To visualize complementation, the accumulation of LLOs was determined. Patients’ cells transfected with the control vector retained the underglycosylation phenotype, characterized by the accumulation of lipid-linked Man5GlcNAc2 and Man9GlcNAc2 as the main oligosaccharides. By contrast, patients’ cells infected with the Lec35-expressing retrovirus showed a restored normal LLO profile, primarily the mature lipid-linked Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide was detected (Table 2).

Table 2.

Complementation of the deficiency in LLO biosynthesis in patient fibroblast by expression of Lec35 cDNA

Discussion

Here we present the identification of mutations in the Lec35/MPDU1 gene, recently located on chromosome 17 and termed MPDU1 (29), as the primary cause for a novel type of CDG, to which we assign the designation If. At a cellular level, this type of CDG-I is characterized by the accumulation of a defined set of intermediates in LLO biosynthesis: the Man9GlcNAc2 and the Man5GlcNAc2 oligosaccharides were the major species detected, but complete Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide was also detected. Interestingly, the Glc3Man5GlcNAc2 was observed in fibroblasts derived from patient S. This oligosaccharide is transferred to protein, because we detect protein-bound oligosaccharides that derived from this incompletely assembled but glucosylated OTase substrate in patient A- and S-derived fibroblasts.

In this limited sample of patients, the severity of the clinical phenotype correlated with the accumulation of intermediates of core oligosaccharide and with the transfer of truncated oligosaccharides to protein: patient S, homozygous for a mutation that alters a conserved residue in the Lec35 protein sequence, has the most severe deficiencies at the cellular and molecular level. The very dramatic clinical picture reflects this. In patient L, we detected heterozygous mutations that either eradicate the start codon on the maternal allele or lead to a frameshift resulting in the expression of a hydrophilic instead of a very hydrophobic C-terminal part of the Lec35 protein from the paternal allele (Figure 4). We hypothesize that neither of these two alleles express functional Lec35p; however, we cannot exclude the possibility that the truncated Lec35 protein remains partially active. We assume that the absence of Lec35p function is tolerated at a cellular level, and to a certain extent, also at the systemic level. This observation is supported by the existence of mutant CHO cells that do not harbor a functional Lec35/MPDU1 allele (29).

The ability to complement the deficiency in LLO biosynthesis in patient-derived cells by expression of a normal Lec35 cDNA shows that the Lec35 deficiency is the primary cause of the disease.

Mutant Lec35 CHO cell lines were shown to accumulate the Man5GlcNAc2 LLO intermediate and to be unable to produce Man6GlcNAc2 or longer intermediates, although the substrates for these reactions, Dol-P-Man and Dol-P-Glc, were present and the glycosyltransferase activities seemed to be normal (44, 45). A recent analysis of the Lec35 mutant phenotype showed that the use of Dol-P-Man in the process of C-mannosylation and GPI anchoring and Dol-P-Glc–dependent reactions in the ER also require Lec35p activity in vivo. Interestingly, the deficiency can be complemented in vitro by the addition of detergent (29). The accumulation of the lipid-linked Man9GlcNAc2 in patients’ fibroblasts (Figure1) supports the finding regarding Dol-P-Glc use. We also observed a reduced level of the GPI-anchored CD59 protein at the cell surface of fibroblasts of two patients, suggesting a deficiency in GPI-anchor biosynthesis (data not shown). However, the simultaneous build-up of Man5GlcNAc2, Glc3Man5GlcNAc2, Man9GlcNAc2, and Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 (patient S, Figure1) is not explained by a shortage of either Dol-P-Man or Dol-P-Glc and also makes a deficiency in a Dol-P-Man or a Dol-P-Glc “flippase” (46, 47) activity in these cells unlikely. Instead, it implies that these substrates are present, but cannot be used efficiently. As suggested by Lehrman and coworkers (29), we consider the role of the Lec35 protein as a dolichol chaperone required for the lateral distribution of Dol-P-Man and Dol-P-Glc within the ER membrane. Studies on the influence of dolichol and its derivatives on the properties of model membranes revealed that these molecules do not distribute homogeneously in the lipid bilayer but might aggregate and form clusters within the membrane (48, 49). We propose that in the absence of the Dol-(P) chaperone Lec35p, specific Dol-P-Man and Dol-P-Glc clusters (or rafts) form within the membrane at the place of their synthesis and translocation. Within the framework of our hypothesis, the aggregation of these components required for the synthesis of the LLO substrate reduces the relative local concentration of the different substrates. When two such rafts come in close contact with each other, the biosynthesis can continue: if the Dol-PP-Man5 domain encounters a Dol-P-Man domain, synthesis up to Dol-PP-GlcNAc2Man9 proceeds; if a Dol-P-Glc raft is in close proximity, synthesis of the Dol-PP-GlcNAc2Man5Glc3 occurs. The limited access of the OTase complex to the completely assembled, but aggregated, Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 oligosaccharide might be an additional reason for the hypoglycosylation observed in CDG-If patients, because completely assembled oligosaccharide was detected in patients’ fibroblasts.

The identification of mutations in the Lec35/MPDU1 locus as the cause of a severe form of CDG (CDG-If) would not have been possible without the knowledge gained from mutant CHO cells altered in the N-linked glycosylation process (29, 44, 45, 50–52). Conversely, the analysis of the deficiencies observed in CDG-If patients might lead to an understanding of Lec35 function at a cellular and molecular level. Mutant cell lines will be a valuable tool to experimentally address the function of Lec35p, but the impact of its deficiency at the systemic level may only be clarified by targeted gene disruption in mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of I. Korn-Lubezki and S. Revel-Vilk, Bikur Cholim Hospital, Jerusalem, and E. Smeets, Center for Human Genetics, University of Leuven. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grants 31-57082.99 to M. Aebi., 31-58577.99 to T. Hennet). J. Jaeken, G. Matthijs, E. Berger, T. Hennet, and M. Aebi are supported by a grant from the European Community (Euroglycan network, QLG1-CT-2000-00047).

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 1579.

Barbara Schenk’s present address is: Dualsystems Biotech, Zürich, Switzerland.

Barbara Schenk and Timo Imbach contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Freeze HH, Aebi M. Molecular basis of carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndromes type I with normal phosphomannomutase activity [erratum 2000, 1500:349]. . Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999; 1455:167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaeken, J., Matthijs, G., Carchon, H., and van Schafftingen, E. 2001. Defects of N-glycan synthesis. In The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseases. C.R. Scriver, A.L. Beaudet, W.S. Sly, and D. Valle, editors. McGraw-Hill. New York, USA. 1601–1622.

- 3.Krasnewich D, Gahl WA. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome. Adv Pediatr. 1997;44:109–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aebi M, Hennet T. Congenital disorders of glycosylation: genetic model systems lead the way. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:136–141. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01925-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varki A. Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helenius A, Aebi M. Intracellular functions of N-linked glycans. Science. 2001;291:2364–2369. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aebi M, et al. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndromes become congenital disorders of glycosylation: an updated nomenclature for CDG. Glycobiology. 2000;10:III-V. doi: 10.1023/a:1017249723165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Schaftingen E, Jaeken J. Phosphomannomutase deficiency is a cause of carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type I. FEBS Lett. 1995;377:318–320. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthijs G, et al. Mutations in PMM2, a phosphomannomutase gene on chromosome 16p13, in carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein type I syndrome (Jaeken syndrome) [erratum 1997, 16:316] Nat Genet. 1997;16:88–92. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niehues R, et al. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type Ib. Phosphomannose isomerase deficiency and mannose therapy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1414–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeken J, et al. Phosphomannose isomerase deficiency: a carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome with hepatic-intestinal presentation. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1535–1539. doi: 10.1086/301873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burda P, et al. A novel carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome characterized by a deficiency in glucosylation of the dolichol-linked oligosaccharide. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:647–562. doi: 10.1172/JCI2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imbach T, et al. A mutation in the human ortholog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae ALG6 gene causes carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type-Ic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6982–6987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imbach T, et al. Multi-allelic origin of congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG)-Ic. Hum Genet. 2000;106:538–545. doi: 10.1007/s004390000293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Körner C, et al. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type V: deficiency of dolichyl-P-Glc:Man9GlcNAc2-PP-dolichyl glucosyltransferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13200–13205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Körner C, et al. Carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome type IV: deficiency of dolichyl-P-Man:Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-dolichyl mannosyltransferase. EMBO J. 1999;18:6816–6822. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imbach T, et al. Deficiency of dolichol-phosphate-mannose synthase-1 causes congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ie. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:233–239. doi: 10.1172/JCI8691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S, et al. Dolichol phosphate mannose synthase (DPM1) mutations define congenital disorder of glycosylation Ie (CDG-Ie) J Clin Invest. 2000;105:191–198. doi: 10.1172/JCI7302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeken J, et al. Carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome type II: a deficiency in Golgi localised N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferase II. Arch Disease Childhood. 1994;71:123–127. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.2.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Praeter CM, et al. A novel disorder caused by defective biosynthesis of N-linked oligosaccharides due to glucosidase I deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1744–1756. doi: 10.1086/302948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubke T, Marquardt T, von Figura K, Korner C. A new type of carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome due to a decreased import of GDP-fucose into the Golgi. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25986–25989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.25986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burda P, Aebi M. The dolichol pathway of N-linked glycosylation. . Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999; 1426:239–257. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirschberg CB, Snider MD. Topography of glycosylation in the rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Q, Lennarz WJ. Oligosaccharyltransferase: a complex multisubunit enzyme of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;266:684–689. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silberstein S, Gilmore R. Biochemistry, molecular biology, and genetics of the oligosaccharyltransferase. FASEB J. 1996;10:849–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knauer R, Lehle L. The oligosaccharyltransferase complex from yeast. . Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999; 1426:259–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spiro RG. Glucose residues as key determinants in the biosynthesis and quality control of glycoproteins with N-linked oligosaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35657–35660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapman A, Trowbridge IS, Hyman R, Kornfeld S. Structure of the lipid-linked oligosaccharides that accumulate in class E Thy-1-negative mutant lymphomas. Cell. 1979;17:509–515. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anand M, et al. Requirement of the Lec35 gene for all known classes of monosaccharide-P-dolichol-dependent glycosyltransferase reactions in mammals. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:487–501. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Packer, R.J., and Bolton, B.J. 1998. Immortalisation of B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. In Cell biology: a laboratory manual. J.E. Celis, editor. Academic Press. San Diego, USA. 178–185.

- 31.de Jong G, van Eijk HG. Microheterogeneity of human serum transferrin: a biological phenomenon studied by isoelectric focusing in immobilized pH gradients. Electrophoresis. 1988;9:589–598. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150090921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zufferey R, et al. STT3, a highly conserved protein required for yeast oligosaccharyl transferase activity in vivo. EMBO J. 1995;14:4949–4960. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elmberger PG, Eggens I, .Dallner G. Conditions for quantitation of dolichyl phosphate, dolichol, ubiquinone and cholesterol by HPLC. Biomed Chromatogr. 1989;3:20–28. doi: 10.1002/bmc.1130030106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morgenstern JP, Land H. Advanced mammalian gene transfer: high titre retroviral vectors with multiple drug selection markers and a complementary helper-free packaging cell line. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3587–3596. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.12.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pear, W.S., Scott, M.L., and Nolan, G.P. 1990. Generation of high titer, helper-free retrovirus by transient transfection. In Methods in molecular medicine: gene therapy protocols. P. Robbins, editor. Humana Press. Totowa, New Jersey, USA. 41–57.

- 36.Yamashita K, et al. Sugar chains of serum transferrin from patients with carbohydrate deficient glycoprotein syndrome. Evidence of asparagine-N-linked oligosaccharide transfer deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5783–5789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burda P, Jakob CA, Beinhauer J, Hegemann JH, Aebi M. Ordered assembly of the asymmetrically branched lipid-linked oligosaccharide in the endoplasmic reticulum is ensured by the substrate specificity of the individual glycosyltransferases. Glycobiology. 1999;9:617–625. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.6.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spiro, R.G. 2000. Processing enzymes involved in the deglucosylation of N-linked oligosaccharides of glycoproteins: glucosidases I and II and endomannosidase. In Carbohydrate in chemistry and biology. B. Ernst, G.W. Hart, and P. Sinay, editors. Wiley-VHC. Weinheim, Germany. 65–79.

- 39.Herscovics A. Processing glycosidases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999; 1426:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parodi AJ. Role of N-oligosaccharide endoplasmic reticulum processing reactions in glycoprotein folding and degradation. Biochem J. 2000;348:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferro-Novick S, Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Yeast secretory mutants that block the formation of active cell surface enzymes. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:35–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenwald AG, Stanley P, Krag SS. Control of carbohydrate processing: increased beta-1,6 branching in N-linked carbohydrates of Lec9 CHO mutants appears to arise from a defect in oligosaccharide-dolichol biosynthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:914–924. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rip JW, Rupar CA, Ravi K, Carroll KK. Distribution, metabolism and function of dolichol and polyprenols. Prog Lipid Res. 1985;24:269–309. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(85)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng YC, Lehrman MA. A block at Man5GlcNAc2-pyrophosphoryldolichol in intact but not disrupted castanospermine and swainsonine-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2296–2305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camp LA, Chauhan P, Farrar JD, Lehrman MA. Defective mannosylation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol in Lec35 Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6721–6728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rush JS, Waechter CJ. Transmembrane movement of a water-soluble analogue of mannosylphosphoryldolichol is mediated by an endoplasmic reticulum protein. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:529–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rush JS, van Leyen K, Ouerfelli O, Wolucka B, Waechter CJ. Transbilayer movement of Glc-P-dolichol and its function as a glucosyl donor: protein-mediated transport of a water-soluble analog into sealed ER vesicles from pig brain. Glycobiology. 1998;8:1195–1205. doi: 10.1093/glycob/8.12.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chojnacki T, Dallner G. The biological role of dolichol. Biochem J. 1988;251:1–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2510001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valtersson C, et al. The influence of dolichol, dolichol esters, and dolichyl phosphate on phopsholipid polymorphism and fluidity in model membranes. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:2742–2751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLuca AW, Rush JS, Lehrman MA, Waechter CJ. Mannolipid donor specificity of glycosylphosphatidylinositol mannosyltransferase-I (GPIMT-I) determined with an assay system utilizing mutant CHO-K1 cells. Glycobiology. 1994;4:909–915. doi: 10.1093/glycob/4.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lehrman MA, Zeng Y. Pleiotropic resistance to glycoprotein processing inhibitors in Chinese hamster ovary cells. The role of a novel mutation in the asparagine-linked glycosylation pathway. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1584–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ermonval M, et al. Truncated N-glycans affect protein folding in the ER of CHO-derived mutant cell lines without preventing calnexin binding. Glycobiology. 2000;10:77–87. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]