Abstract

This study investigated the role of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) during Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection of mice. We show that ICAM-1 is expressed in and around granulomas on day 4 of infection in wild-type mice. However, when naive ICAM-1−/− mice were challenged with a sublethal dose of serovar Typhimurium, there were no detectable differences in systemic bacterial burden over the first 9 days of infection compared to wild-type control mice. When mice were immunized with the S. enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strain SL2361 and then challenged with the virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strain C5, 100% of the ICAM-1−/− mice succumbed to infection, compared to 30% of wild-type mice. T-cell responses, as measured by activation via interleukin-2 production, as well as antibody responses were comparable in the ICAM-1−/− and wild-type mice. Following challenge, counts in organs were significantly higher in the ICAM-1−/− mice, and histological examination of organs showed pathological differences. Strain SL3261-immunized wild-type mice had cellular infiltrate and normal granuloma formation in the liver and spleen on days 5 and 10 after challenge with strain C5. ICAM-1−/− mice had a similar infiltrate on day 5, whereas on day 10 the infiltrate was more widespread and there were fewer macrophages associated with the granulomas. High circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha and gamma interferon, as well as a high burden of strain C5 in the blood, accompanied the differences in histopathology. In this study we show that ICAM-1 plays a critical role during rechallenge of immunized mice with virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium.

Salmonella infections continue to be a major health hazard worldwide. The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium mouse model has facilitated a better understanding of the mechanisms of pathogenesis and immunity involved in infection, which may lead to a more rational approach to both treatment of and development of vaccines against human and veterinary salmonellosis. Salmonella growth in the reticuloendothelial system of mice is controlled by the innate resistance Nramp-1 gene expressed by macrophages (20). Lethally infected mice succumb to infection when bacterial numbers reach 108 CFU per organ (30). In sublethally infected mice, bacterial growth is controlled at approximately 1 week postinoculation (23). Early host responses that are critical for preventing bacterial spread and growth include the production of NADPH oxidase early in infection (29) and the recruitment of bone marrow-derived macrophages (12) coinciding with the formation of organized granulomas (28, 37). The majority of salmonellae are localized within phagocytes in the granulomas in both the liver and spleen (37). These early responses do not require T cells, as nude, T-cell receptor αβ knockout, and antibody-depleted (CD4+ and CD8+) mice can suppress Salmonella growth (9, 12).

The production of a number of cytokines and soluble factors is important during the early phases of Salmonella infection. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-18, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and inducible nitric oxide synthase are all critical for the control of Salmonella growth in vivo (1, 18, 19, 24, 25, 27-29, 32, 34, 44). TNF-α is required for the localization of NADPH oxidase and the formation and organization of the salmonella-containing granulomas (28, 46) and is needed throughout the infection, as depletion of TNF-α after bacterial growth is controlled causes a relapse in granuloma organization and resurgence of bacterial growth (31). IL-12 and IL-18 work both independently and synergistically on NK cells and T cells inducing the production of IFN-γ (25, 27, 36, 48). IFN-γ promotes the Salmonella killing mechanisms of macrophages (17), which include inducible nitric oxide synthase (1, 29, 44).

Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1 or CD54) is a 55-kDa protein that can be produced by many cell types and can be expressed on the cell surface or secreted extracellularly (8). ICAM-1 is composed of five immunoglobulin superfamily extracellular domains and is the ligand for leukocyte function antigen 1 (42) and macrophage antigen 1 (5). Expression of ICAM-1 is strongly up regulated by inflammatory mediators (41). The primary role of ICAM-1 and its interactions with the ligands is the facilitation of the migration of leukocytes towards sites of stimuli. Studies using animal models of infection have added to our understanding of leukocyte migration in vivo. Leukocyte recruitment models such as enterotoxin or glycogen injection of mice show reduced leukocyte accumulation when ICAM-1 or its ligands are blocked with antibody (14, 43). In vivo, multiple cell types express ICAM-1 in the face of infections caused by Haemophilus influenzae, Trypanosoma cruzi, Schistosoma mansoni, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (7, 21, 22, 33, 47).

The generation of ICAM-1−/− mice has enabled a more thorough examination of the specific role of this adhesion molecule during infection (40). ICAM-1−/− mice showed a greater intensity and ascending disease for the first 3 weeks during a genital chlamydial infection. However, mice still cleared the infection, albeit more slowly than control animals (13). ICAM-1−/− mice infected with Candida albicans had diminished body weights associated with an increased fungal load in both the kidney and brain compared to control mice. Neutrophil recruitment, indicative of a response seen in wild-type animals, was abridged in ICAM-1−/− mice (4). With respiratory infections, differences in lymphocyte numbers were observed in the lungs of H. influenzae-infected ICAM-1−/− mice compared to control animals (39). ICAM-1−/− mice infected with M. tuberculosis controlled infection for the first 90 days, with a reduction in granuloma formation and leukocyte numbers in the lung. However, these mice failed to mount a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to M. tuberculosis antigens (15). During a chronic long-term M. tuberculosis infection, ICAM-1−/− mice have an increased bacterial burden in their lungs compared to control mice and succumb to infection around day 136 postchallenge. These mice have widespread infiltrate with no detectable granuloma organization (38).

Here we investigated the role that ICAM-1 plays in the recruitment of leukocytes to primary and secondary sites of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− (40) mice were purchased from B&K Universal Ltd. and Jackson Laboratory, respectively. ICAM-1−/− mice were backcrossed to the C57BL/6 background for nine generations when purchased. Age- and sex-matched groups were used when older than 6 weeks.

Bacteria.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 is an aroA attenuated live vaccine strain (10), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium purE and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 are strains of intermediate virulence (35), and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 is a fully virulent strain with an oral 50% lethal dose of 106 CFU (11). Bacteria were grown at 37°C as stationary overnight cultures in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Difco).

Preparation of inocula.

For oral inoculation, overnight cultures were centrifuged at 15,191 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 1/10 of the original volume in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Bacteria were administered with a blunt-tipped gavage needle. For intravenous inoculation, overnight cultures were diluted in PBS and injected into the lateral tail vein. Inocula were cultured retrospectively on LB agar to determine the administered dose.

Enumeration of bacteria in organs.

Mice were sacrificed by cardiac exsanguination under anesthesia. Serum was prepared by centrifugation at 16,200 × g for 5 min and stored at −20°C. Organs were aseptically removed and homogenized with a Colworth stomacher in 5 ml of distilled water (26). Viable counts were determined by spotting 20 μl of homogenate onto LB agar. For blood cultures, blood was collected into heparin (300 U/ml of blood), and then 100 μl was mixed with molten LB agar and pour plated. All plates were incubated overnight at 37°C.

Immunohistochemistry protocol.

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and organs were aseptically removed and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was mounted in OTC, and 5-μm sections were cut with a Shanndon cryostat. Sections were transferred to poly-l-lysine-coated slides.

After air drying for 30 min, the tissue was fixed in 100% acetone for 10 min. Following 2 min in water, the slides were transferred to 70% methanol containing 0.6% hydrogen peroxide and left for 30 min. After washes in PBS, the tissue was blocked with normal goat serum (1:10 in PBS) for 10 min, and anti ICAM-1 antibody diluted 1:1,000 in PBS was added. The slides were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and then washed twice in PBS. The tissue was then coated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody for 1 h, followed by three washes in PBS. The tissue was submerged in Sigma Fast diaminobenzidine substrate (15 ml of Tris-buffered saline, 12 μl of H2O2, and one 10-μg diaminobenzidine tablet [the substrate was filtered prior to use]). The slides were removed to water after 10 min of incubation at room temperature. Sections were counterstained for 30 s in Mayer's hemalum and dehydrated through ethanol, beginning with 70% (2 min) and followed by 90% (2 min), 100% (4 min), and 2 min in Histoclear. Slides were mounted in dibutyl phtalate xylene, allowed to dry, and viewed by light microscopy.

Histology.

Small pieces of tissue were fixed in 4% formaldehyde. The tissue was paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Determination of total IgG in mouse sera.

Nunc Maxisorp plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 50 μl of a 2-μg/ml solution of purified recombinant tetanus toxin fragment C (TetC) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in coating buffer (0.1 M Na2HPO4 at pH 9). Following one wash with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), the plates were blocked with 100 μl of 3.0% bovine serum albumin in PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Plates were then washed once with PBS-T, and sera from experimental animal groups were added as follows: 3 μl of serum was added to 27 μl of PBS-T with 0.2% BSA (PBS-BT), and 12.5 μl of this was then added to 125 μl of PBS-BT in the top well and then diluted with PBS-BT fivefold down the plate. Each plate contained control wells with preimmune sera, PBS alone, and known positive immune sera and was incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-T, anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies conjugated to HRP, diluted 1/1,000 in PBS-BT, were added at 100 μl per well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Following five washes with PBS-T, the plates were developed with the Sigma Fast o-phenylene diamine dihydrochloride tablet set (100 μl per well). The reaction was stopped after 20 min with 20 μl of 2.5 M H2SO4. Optical densities (ODs) were read at 490 nm, and were titers expressed as the reciprocal of the dilution giving an OD of 0.3.

Determination of IgG subclasses in mouse sera.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol described above was modified as follows to determine the IgG subclass titers in mouse sera. Rat monoclonal antibodies against different mouse IgG subclasses conjugated to biotin (PharMingen) were used as the secondary antibody. Anti-IgG1, anti-IgG2a, and anti-IgG2b were used at dilutions of 1:4,000, 1:1,000, and 1:1,000, respectively. Subclass conjugate antibodies were calibrated against purified isotype antibodies as antigens to enable direct comparisons. To detect the biotin-conjugated antibodies, plates were washed four times in PBS-T and then incubated with (per well) 50 μl of streptavidin-HRP diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-T. Plates were developed and titers were measured as described above.

Measurement of cellular responses. (i) Proliferation assay.

Immunized and control mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and their spleens were aseptically removed into RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM glutamine, 10−5 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml (RPMI+). Single-cell suspensions were prepared by pushing spleens through a 100-μm-pore-size cell strainer (Becton Dickinson). Cells were centrifuged at 420 × g for 5 min, followed by 5 min of incubation with a 0.5% Tris-ammonium chloride (pH 7.2) solution to remove erythrocytes. The cells were washed with RPMI twice and then resuspended in 1 ml of RPMI+. Viable splenocytes were counted by trypan blue exclusion.

Cells were seeded, in duplicate, into round-bottom 96-well tissue culture plates at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/well in a volume of 200 μl. Splenocytes were restimulated with either purified TetC (5 μg/ml) or Salmonella whole-cell lysate (15 μg/ml) in a final volume of 200 μl. Control wells were stimulated with concanavalin A or RPMI+. Plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, and then supernatants were stored at −80°C for subsequent cytokine ELISAs.

(ii) Cytometric bead array.

Assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following standard curve calibration, 50 μl of mixed capture beads were added to 50 μl of each sample serum and mixed. Fifty microliters of R-phycoerythrin detection reagent was added to each sample tube and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. A 1-ml volume of wash buffer was added to each vortex tube and centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min. After the supernatant was discarded, a further 300 μl of wash buffer was added and the pellet was resuspended. Samples were then analyzed on a flow cytometer.

Statistical analysis.

The Mann-Whitney U test or permutation test with a two-sample t test-type statistic was used to determine the significance of differences between controls and experimental groups. Differences were considered significant at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

ICAM-1 is up regulated during a S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infection.

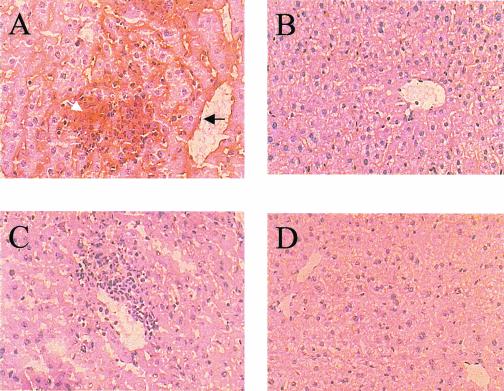

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were infected intravenously with 104 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 organisms. Strain M525 exhibits an intermediate level of virulence in mice and generates significant liver pathology. Animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation on day 4 of infection; livers were removed and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Uninfected mice were used as controls. Tissue sections were immunostained with anti-CD54 antibodies. Figure 1 shows that ICAM-1 is expressed during a primary M525 infection. Staining was observed throughout the granuloma and more intensely around the blood vessels close to the granuloma (Fig. 1A). There was no significant staining in the tissue of naive control mice (Fig. 1B) or in the ICAM-1−/− sections (Fig. 1C and D). The staining shown is representative of that for four mice per group.

FIG. 1.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were infected intravenously with 104 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 organisms; naive mice were used as controls. (A and C) Livers from infected C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/−, respectively; (B and D) naive controls for panels A and C, respectively. The arrow shows ICAM-1 staining in and around the granuloma (white) and blood vessels (black). Magnification, ×200.

ICAM-1 deficiency has no obvious effect on the early control of a primary S. enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 infection in vivo.

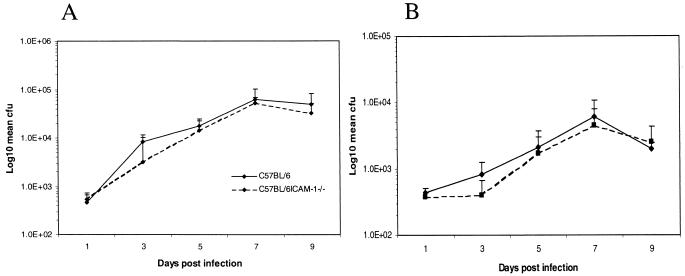

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were injected intravenously with 104 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium M525 organisms. Mice were sacrificed at various times thereafter (Fig. 2), and total bacterial viable counts in liver and spleen were determined. At the early time points (days 1 to 9) of a primary Salmonella infection, there were no significant differences in bacterial counts in either the spleen or liver between C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice.

FIG. 2.

Mice were infected as described for Fig. 1. Total counts from the spleen (A) and liver (B) were determined on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 of infection. Counts are expressed as mean log10 CFU per organ for four mice ± standard deviation. The results are from one of two experiments that gave similar results.

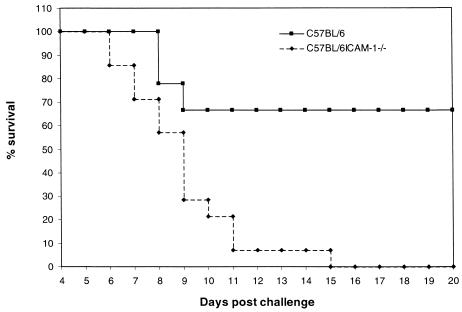

ICAM-1−/− mice are unable to control a virulent challenge following immunization.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were injected intravenously with 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms and then left for 3 months. Livers and spleens from three mice were assessed for the presence of the SL3261 aroA immunizing strain on days 49 and 70 postimmunization. On day 49 postimmunization, wild-type mice had mean bacterial loads (± standard deviations) of 613 ± 506 and 410 ± 107, and ICAM-1−/− mice had loads of 443 ± 160 and 250 ± 143, in the spleen and liver, respectively. By day 70, all six mice sampled were found to be clear of this strain. The remaining SL3261-immunized mice were then challenged orally with 1010 viable virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 organisms. Five naive unimmunized mice from each group were similarly challenged. The mice were monitored and sacrificed by cervical dislocation when they showed overt signs of disease. Data from two separate experiments were pooled, and the percent survival was plotted against days postinfection (Fig. 3). SL3261-immunized ICAM-1−/− mice exhibited reduced protection against wild-type C5 challenge compared to immunized C57BL/6 control mice. Figure 3 shows that 100% of the SL3261-immunized ICAM-1−/− mice challenged succumbed to C5 infection by day 15 postchallenge, compared to 30% of the wild-type mice. Naive ICAM-1−/− mice succumbed to C5 infection 1 day earlier than wild-type mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were immunized intravenously with 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms. The mice were left 3 months and then checked for clearance of the immunizing bacteria. Mice were then challenged orally with 1010 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 organisms. The mice were monitored closely and sacrificed at a predetermined end point relating to advanced disease symptoms. Results are expressed as the pooled percent survival from two separate experiments, with a total of 15 mice in each group.

Inability to control a virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium challenge is not due to deficient antibody or T-cell responses.

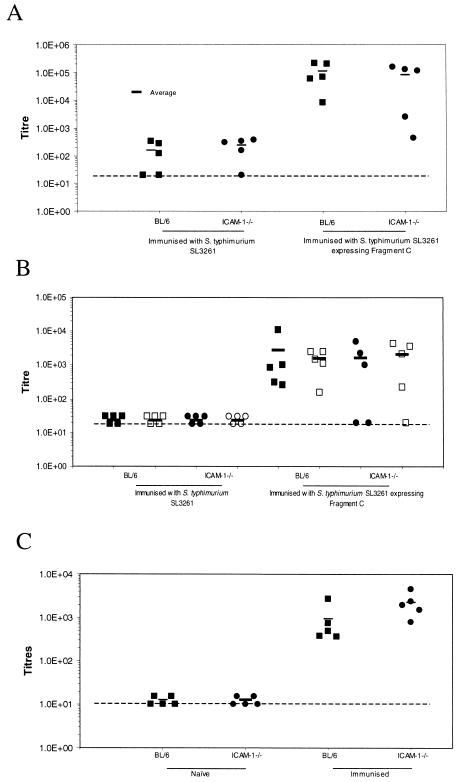

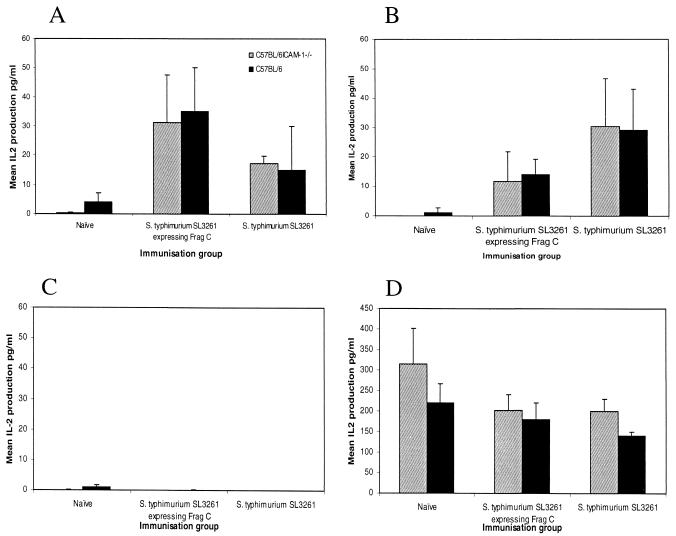

To further investigate possible reasons for the inability of ICAM-1−/− mice to mount a protective immune response, C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were immunized intravenously with either 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms or 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms expressing TetC. This TetC-expressing Salmonella derivative was used to facilitate investigations of both antibody and T-cell responses, since TetC is a good model antigen through which to study antigen-specific responses in vitro and in vivo (6). Unimmunized naive mice were used as controls. Following immunization, groups of mice were left for 1 month and then euthanatized. Figure 4A shows total serum IgG antibody titers to TetC in these mice and naive controls. ICAM-1−/− mice immunized with SL3261 expressing TetC had a serum IgG response similar to that of wild-type mice. Furthermore, when anti-TetC IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses were studied (Fig. 4B), no significant differences between ICAM-1−/− and wild-type mice were observed. In addition, no difference was detected when serum anti LPS antigen responses were examined 3 months after S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 immunization (Fig. 4C). To assess T-cell responses to the surrogate antigen TetC and to Salmonella-associated proteins, splenocytes from immunized mice were stimulated with both purified recombinant TetC and Salmonella whole-cell lysate. Supernatants were analyzed for IL-2 as a surrogate marker of T-cell activation. Splenocytes from immunized ICAM-1−/− mice produced IL-2 following stimulation with both antigens at a level comparable to that observed for wild-type murine spleen cells extracted from immunized mice (Fig. 5). These data suggest that antibody and T-cell specific responses to Salmonella-associated antigens are not detectably attenuated.

FIG. 4.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were immunized with 105 TetC-expressing S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms. (A) Total TetC-specific IgG titers from naive animals and animals immunized 1 month previously. (B) Antibody profiles were further analyzed by examining IgG1 (closed symbols) and IgG2a (open symbols) levels in the sera of immunized and naive animals. (C) Anti-Salmonella LPS antibody titers 3 months after immunization. All titers are expressed as log10 at an OD of 0.3. The dashed lines represent the level of naive antibody levels. The results are from one of two experiments that gave similar results.

FIG. 5.

Splenocytes isolated from the animals used for Fig. 4 were cultured in vitro and stimulated with either TetC (A) or S. enterica serovar Typhimurium whole-cell lysate (B) to study cellular responses. Stimulations with medium alone (C) and concanavalin A (D) were used as controls. Cells were incubated for 24 h, and then supernatants were kept at −80°C until analyzed. IL-2 production was measured by ELISA and was used as an indication of T-cell activation. The mean IL-2 production ± standard deviation from three mice per group is shown.

Bacterial enumeration and histological examination reveals differences in the recruitment of cells during a virulent challenge.

C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were immunized intravenously with 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms. The immunized mice were then challenged orally with 108 viable virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 organisms 3 months later. Five naive animals from each group were also challenged with C5. Groups of wild-type and ICAM-1−/− mice were sacrificed on days 3, 5, and 10 postchallenge, and the Salmonella burdens in Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and blood were determined. Tissues were also fixed for histological examination.

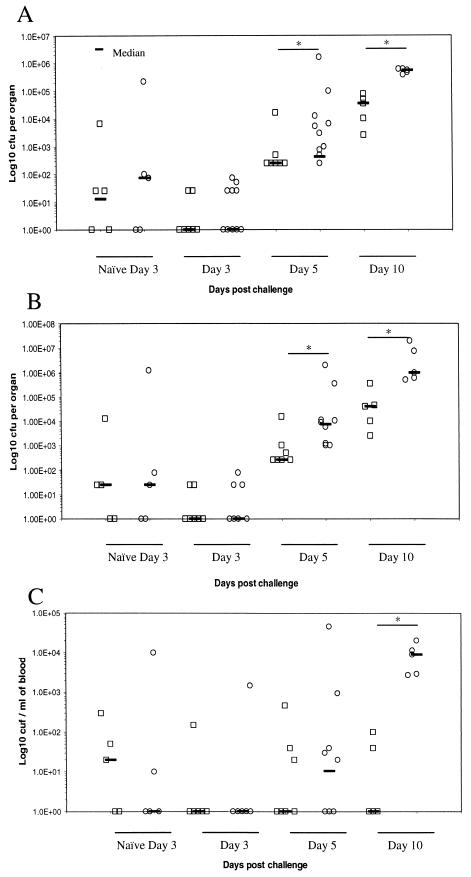

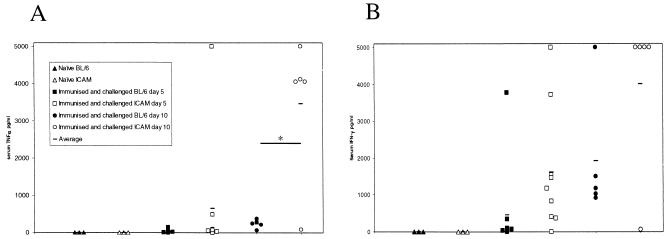

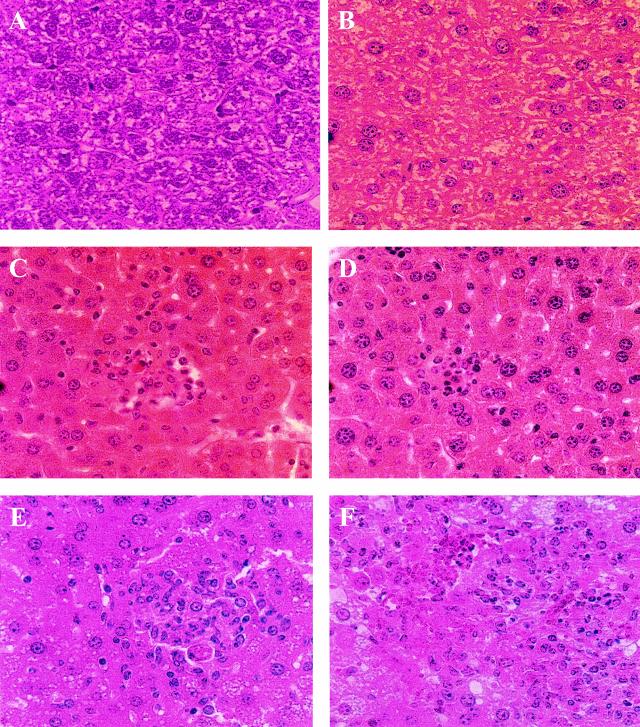

The numbers of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 in the Peyer's patches and mesenteric lymph nodes were similar in ICAM-1−/− and wild-type mice at all time points (data not shown). However, the average counts in the spleens and livers of ICAM-1−/− mice were significantly different from those in wild-type mice on days 5 (P = 0.001 and 0.043, respectively) and 10 (P = 0.008 and 0.008, respectively) postinfection, although they were similar on day 3 (Fig. 6A and B). Counts in the blood were similar up to day 10 postchallenge, when a significantly (P = 0.008) greater C5 burden was detected in ICAM-1−/− mice (Fig. 6C). These differences also correlated with significantly higher circulating levels of TNF-α (P = 0.015) and increased IFN-γ (P = 0.083) in the ICAM-1−/− mice (Fig. 7). Histological examination of livers from these mice showed differences in the organization of leukocyte infiltrates. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261-immunized and C5-challenged mice sacrificed on day 5 were similar in the organization and type of leukocytes associated with focal lesions (Fig. 8C and D). Both ICAM-1−/− and control mice challenged with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 had microabscesses rich in neutrophils at day 5. By day 10 postchallenge, control mice had developed more organized granulomas, which contained a mix of neutrophils and macrophages (Fig. 8E). In contrast, ICAM-1−/− mice had a more unorganized infiltration of leukocytes and focal lesions consisting mainly of neutrophils, with very few macrophages (Fig. 8F). A similar pattern of pathology was also seen in the spleens of infected animals (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

C57BL/6 (squares) and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− (circles) mice were immunized intravenously with 105 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 organisms and challenged orally 3 months later with 108 S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 organisms. Naive C57BL/6 and C57BL/6ICAM-1−/− mice were also challenged and sacrificed on day 3. Total counts from the spleen (A), liver (B), and blood (C) were determined on days 3, 5, and 10 postchallenge. Counts are expressed as log10 CFU per organ or per milliliter of blood from individual mice. *, P < 0.05 as determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

FIG. 7.

Blood taken from the mice used for Fig. 6 was analyzed by cytometric bead assay to determine levels of TNF-α (A) and IFN-γ (B) levels, expressed as picograms per milliliter of plasma from individual mice. *, P < 0.05 as determined by a permutation test using a two-sample t test-type statistic.

FIG. 8.

Organs from mice immunized and challenged as described for Fig. 5 were processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The images represent sections of liver from naive mice (A and B), challenged wild-type mice at days 5 and 10 (C and E, respectively), and challenged ICAM-1−/− mice at days 5 and 10 (D and F, respectively). Images are representative of those for the five animals at each time point. Magnification, ×400.

DISCUSSION

Adhesion molecules play an important role in tissue-specific organization and the recruitment of leukocytes to invading pathogens (4, 14, 38, 43). During S. enterica serovar Typhimurium infection of C57BL/6 mice, ICAM-1 antigen was detected in the liver by immunohistochemistry. ICAM-1 expression was observed in and around the granuloma, with more intense staining on the endothelial cells of blood vessels closest to the granuloma. When ICAM-1−/− mice were infected with serovar Typhimurium, bacterial counts in the livers and spleens were similar to those for control mice during the first 9 days of infection. Indeed, we have been unable to detect any differences in Salmonella counts in naive mice challenged with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains (our observations). Similar observations have been made during M. tuberculosis (15) and C. albicans (4) infections. Even though there was a reduction in leukocyte infiltration, ICAM-1−/− mice infected with M. tuberculosis were able to control infection during the early days of primary infection, although differences were detected later in chronically infected mice, with increased mycobacterial loads in ICAM-1−/− mice (15). Cellular infiltration into the liver and granuloma formation microscopically appear to be unaffected during primary serovar Typhimurium infection in ICAM-1−/− mice. As is the case with many aspects of the immune system, redundancy between adhesion molecules may contribute to explaining these results. ICAM-2 and ICAM-3, molecules functionally related to ICAM-1, have been reported to be expressed at high basal levels (16).

As well as being important in recruitment, ICAM-1 has also been shown to be important as a costimulatory molecule for lymphocyte activation (2, 3, 45). One assessment of the data presented here is that ICAM-1 is important in recall of immunity to Salmonella, as the ICAM-1−/− mice were unable to control a virulent challenge following immunization. However, ICAM-1−/− mice have similar levels of T-cell activation upon restimulation with both Salmonella antigen and surrogate antigens. Similarly, ICAM-1−/− mice mounted comparable antigen-specific serum IgG titers and similar IgG subclass ratios compared to control animals. Thus, simple splenocyte stimulation and antibody studies could not discriminate between the immune responses in ICAM-1−/− and wild-type mice. Others have studied antigen-specific responses associated with infection and ICAM-1 function. Lukacs et al. reported a decrease in antigen-specific T-cell proliferation in vitro in the presence of anti-ICAM-1 antibodies (22). ICAM-1−/− mice infected with M. tuberculosis had a reduced delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, indicating defects in macrophage and other immune cell recruitment (38). A potential hypothesis to explain the increased sensitivity of immunized ICAM-1−/− mice to virulent challenge is that ICAM-1−/− mice fail to efficiently recruit appropriate immune effector cells to sites of secondary infection. Igietseme et al. demonstrated that the high affinity of ICAM-1 for leukocyte function antigen 1 promotes early recruitment and rapid activation of specific Th1 cells (13). If Salmonella-specific Th1 cells were not arriving at sites of infection or were not being adequately stimulated, then an increased bacterial load might be one consequence. In our experiments, counts of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 were similar in the guts of both immunized control and immunized ICAM-1−/− mice succumbing to infection. Counts were 1 log unit higher in the spleens and livers of ICAM-1−/− mice than in those of wild-type animals on day 10 postchallenge. However, the bacterial burden alone may not account for the death of these animals, as numbers as high as 108 to 109 per organ have been reported previously (27). The high numbers of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium C5 detected in the blood of the ICAM-1−/− mice is an indication that bacteria in the liver and spleen may not be restricted to macrophages and granulomas, which have been shown to be important factors in the control of Salmonella growth during infection (31). Along with high levels of circulating bacteria, high levels of TNF-α in serum were detected in ICAM-1−/− mice, indicating that these animals may have been succumbing to endotoxic shock and organ failure.

The liver granulomas formed in S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261-immunized and C5-challenged ICAM-1−/− mice were histologically different from granulomas in control mice, in that there were fewer macrophages associated with them. Macrophages were present in the livers of the challenged ICAM-1−/− mice, but they were dispersed and not localized to foci of infection. An interesting observation with the ICAM-1−/− mice was the higher incidence of apoptotic hepatocytes associated with granulomas (our observation). This could be a consequence of fewer macrophages at sites of infection and a lack of clearance of apoptotic hepatocytes via macrophages.

This leads us to the question of why mice lacking ICAM-1 control a primary infection. This could be due to the relative speed of the infection. In a primary sublethal infection, the bacteria are attenuated in their virulence and as a consequence grow at a lower rate in vivo. During a lethal challenge, a fully virulent strain was used, which is more vigorous and faster growing. Thus, during a primary infection, there may be more time for compensatory mechanisms to facilitate protection. During a virulent challenge, the speed of recruitment is critical, and ICAM-1 is an important molecule in this type of response. Animals that have been challenged with higher doses of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (1010), such as those for Fig. 3, have very few infiltrating leukocytes and show severe hepatic damage (data not shown). We have shown that ICAM-1 contributes to the control of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium challenge following immunization and that this is probably due to recruitment of the appropriate leukocytes to systemic tissues to control bacterial growth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust and BBSRC to Gordon Dougan.

We thank the members of Central Biomedical Services for their help with this work.

Editor: B. B. Finlay

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam, M. S., T. Akaike, S. Okamoto, T. Kubota, J. Yoshitake, T. Sawa, Y. Miyamoto, F. Tamura, and H. Maeda. 2002. Role of nitric oxide in host defense in murine salmonellosis as a function of its antibacterial and antiapoptotic activities. Infect. Immun. 70:3130-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damle, N. K., K. Klussman, P. S. Linsley, and A. Aruffo. 1992. Differential costimulatory effects of adhesion molecules B7, ICAM-1, LFA-3, and VCAM-1 on resting and antigen-primed CD4+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 148:1985-1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damle, N. K., K. Klussman, P. S. Linsley, A. Aruffo, and J. A. Ledbetter. 1992. Differential regulatory effects of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on costimulation by the CD28 counter-receptor B7. J. Immunol. 149:2541-2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis, S. L., E. P. Hawkins, E. O. Mason, Jr., C. W. Smith, and S. L. Kaplan. 1996. Host defenses against disseminated candidiasis are impaired in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J. Infect. Dis. 174:435-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond, M. S., D. E. Staunton, S. D. Marlin, and T. A. Springer. 1991. Binding of the integrin Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) to the third immunoglobulin-like domain of ICAM-1 (CD54) and its regulation by glycosylation. Cell 65:961-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douce, G., M. Fontana, M. Pizza, R. Rappuoli, and G. Dougan. 1997. Intranasal immunogenicity and adjuvanticity of site-directed mutant derivatives of cholera toxin. Infect. Immun. 65:2821-2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frick, A. G., T. D. Joseph, L. Pang, A. M. Rabe, J. W. St. Geme III, and D. C. Look. 2000. Haemophilus influenzae stimulates ICAM-1 expression on respiratory epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 164:4185-4196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gearing, A. J., and W. Newman. 1993. Circulating adhesion molecules in disease. Immunol. Today 14:506-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hess, J., C. Ladel, D. Miko, and S. H. Kaufmann. 1996. Salmonella typhimurium aroA− infection in gene-targeted immunodeficient mice: major role of CD4+ TCR-alpha beta cells and IFN-gamma in bacterial clearance independent of intracellular location. J. Immunol. 156:3321-3326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoiseth, S. K., and B. A. Stocker. 1981. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature 291:238-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hormaeche, C. E. 1979. Natural resistance to Salmonella typhimurium in different inbred mouse strains. Immunology 37:311-318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hormaeche, C. E., P. Mastroeni, A. Arena, J. Uddin, and H. S. Joysey. 1990. T cells do not mediate the initial suppression of a Salmonella infection in the RES. Immunology 70:247-250. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igietseme, J. U., G. A. Ananaba, J. Bolier, S. Bowers, T. Moore, T. Belay, D. Lyn, and C. M. Black. 1999. The intercellular adhesion molecule type-1 is required for rapid activation of T helper type 1 lymphocytes that control early acute phase of genital chlamydial infection in mice. Immunology 98:510-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaeschke, H., A. Farhood, M. A. Fisher, and C. W. Smith. 1996. Sequestration of neutrophils in the hepatic vasculature during endotoxemia is independent of beta 2 integrins and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. Shock 6:351-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson, C. M., A. M. Cooper, A. A. Frank, and I. M. Orme. 1998. Adequate expression of protective immunity in the absence of granuloma formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice with a disruption in the intracellular adhesion molecule 1 gene. Infect. Immun. 66:1666-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juan, M., J. Mullol, J. Roca-Ferrer, M. Fuentes, M. Perez, C. Vilardell, J. Yague, and C. Picado. 1999. Regulation of ICAM-3 and other adhesion molecule expressions on eosinophils in vitro. Effects of dexamethasone. Allergy 54:1293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kagaya, K., K. Watanabe, and Y. Fukazawa. 1989. Capacity of recombinant gamma interferon to activate macrophages for Salmonella-killing activity. Infect. Immun. 57:609-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kincy-Cain, T., J. D. Clements, and K. L. Bost. 1996. Endogenous and exogenous interleukin-12 augment the protective immune response in mice orally challenged with Salmonella dublin. Infect. Immun. 64:1437-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koebernick, H., L. Grode, J. R. David, W. Rohde, M. S. Rolph, H. W. Mittrucker, and S. H. Kaufmann. 2002. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) plays a pivotal role in immunity against Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13681-13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang, T., E. Prina, D. Sibthorpe, and J. M. Blackwell. 1997. Nramp1 transfection transfers Ity/Lsh/Bcg-related pleiotropic effects on macrophage activation: influence on antigen processing and presentation. Infect. Immun. 65:380-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laucella, S., R. Salcedo, E. Castanos-Velez, A. Riarte, E. H. De Titto, M. Patarroyo, A. Orn, and M. E. Rottenberg. 1996. Increased expression and secretion of ICAM-1 during experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasite Immunol. 18:227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukacs, N. W., S. W. Chensue, R. M. Strieter, K. Warmington, and S. L. Kunkel. 1994. Inflammatory granuloma formation is mediated by TNF-alpha-inducible intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J. Immunol. 152:5883-5889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maskell, D. J., C. E. Hormaeche, K. A. Harrington, H. S. Joysey, and F. Y. Liew. 1987. The initial suppression of bacterial growth in a salmonella infection is mediated by a localized rather than a systemic response. Microb. Pathog. 2:295-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mastroeni, P., A. Arena, G. B. Costa, M. C. Liberto, L. Bonina, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1991. Serum TNF alpha in mouse typhoid and enhancement of a Salmonella infection by anti-TNF alpha antibodies. Microb. Pathog. 11:33-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mastroeni, P., S. Clare, S. Khan, J. A. Harrison, C. E. Hormaeche, H. Okamura, M. Kurimoto, and G. Dougan. 1999. Interleukin 18 contributes to host resistance and gamma interferon production in mice infected with virulent Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 67:478-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mastroeni, P., J. A. Harrison, J. A. Chabalgoity, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1996. Effect of interleukin 12 neutralization on host resistance and gamma interferon production in mouse typhoid. Infect. Immun. 64:189-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mastroeni, P., J. A. Harrison, J. H. Robinson, S. Clare, S. Khan, D. J. Maskell, G. Dougan, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1998. Interleukin-12 is required for control of the growth of attenuated aromatic-compound-dependent salmonellae in BALB/c mice: role of gamma interferon and macrophage activation. Infect. Immun. 66:4767-4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastroeni, P., J. N. Skepper, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1995. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibodies on histopathology of primary Salmonella infections. Infect. Immun. 63:3674-3682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mastroeni, P., A. Vazquez-Torres, F. C. Fang, Y. Xu, S. Khan, C. E. Hormaeche, and G. Dougan. 2000. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. II. Effects on microbial proliferation and host survival in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 192:237-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mastroeni, P., B. Villarreal-Ramos, J. A. Harrison, R. Demarco de Hormaeche, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1994. Toxicity of lipopolysaccharide and of soluble extracts of Salmonella typhimurium in mice immunized with a live attenuated AroA Salmonella vaccine. Infect. Immun. 62:2285-2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mastroeni, P., B. Villarreal-Ramos, and C. E. Hormaeche. 1993. Effect of late administration of anti-TNF alpha antibodies on a Salmonella infection in the mouse model. Microb. Pathog. 14:473-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muotiala, A., and P. H. Makela. 1990. The role of IFN-gamma in murine Salmonella typhimurium infection. Microb. Pathog. 8:135-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasreen, N., K. A. Mohammed, M. J. Ward, and V. B. Antony. 1999. Mycobacterium-induced transmesothelial migration of monocytes into pleural space: role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in tuberculous pleurisy. J Infect. Dis. 180:1616-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nauciel, C., and F. Espinasse-Maes. 1992. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha in resistance to Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect. Immun. 60:450-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Callaghan, D., D. Maskell, F. Y. Liew, C. S. Easmon, and G. Dougan. 1988. Characterization of aromatic- and purine-dependent Salmonella typhimurium: attention, persistence, and ability to induce protective immunity in BALB/c mice. Infect. Immun. 56:419-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramarathinam, L., D. W. Niesel, and G. R. Klimpel. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium induces IFN-gamma production in murine splenocytes. Role of natural killer cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 150:3973-3981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richter-Dahlfors, A., A. M. Buchan, and B. B. Finlay. 1997. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 186:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders, B. M., A. A. Frank, and I. M. Orme. 1999. Granuloma formation is required to contain bacillus growth and delay mortality in mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunology 98:324-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinikovic, B., M. Larbig, H. J. Hedrich, R. Pabst, and T. Tschernig. 2001. The numbers of leukocyte subsets in lung sections differ between intercellular adhesion molecule-1−/−, lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1−/− mice and intercellular adhesion molecule-1−/− mice after aerosol exposure to Haemophilus influenzae type-b. Virchows Arch. 438:362-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sligh, J. E., Jr., C. M. Ballantyne, S. S. Rich, H. K. Hawkins, C. W. Smith, A. Bradley, and A. L. Beaudet. 1993. Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8529-8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Springer, T. A. 1990. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346:425-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staunton, D. E., M. L. Dustin, H. P. Erickson, and T. A. Springer. 1990. The arrangement of the immunoglobulin-like domains of ICAM-1 and the binding sites for LFA-1 and rhinovirus. Cell 61:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tessier, P. A., P. H. Naccache, K. R. Diener, R. P. Gladue, K. S. Neote, I. Clark-Lewis, and S. R. McColl. 1998. Induction of acute inflammation in vivo by staphylococcal superantigens. II. Critical role for chemokines, ICAM-1, and TNF-alpha. J. Immunol. 161:1204-1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umezawa, K., T. Akaike, S. Fujii, M. Suga, K. Setoguchi, A. Ozawa, and H. Maeda. 1997. Induction of nitric oxide synthesis and xanthine oxidase and their roles in the antimicrobial mechanism against Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 65:2932-2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Seventer, G. A., Y. Shimizu, K. J. Horgan, and S. Shaw. 1990. The LFA-1 ligand ICAM-1 provides an important costimulatory signal for T cell receptor-mediated activation of resting T cells. J. Immunol. 144:4579-4586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vazquez-Torres, A., J. Jones-Carson, P. Mastroeni, H. Ischiropoulos, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. I. Effects on microbial killing by activated peritoneal macrophages in vitro. J. Exp. Med. 192:227-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, L., and R. L. Tarleton. 1996. Persistent production of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines and associated MHC and adhesion molecule expression at the site of infection and disease in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infections. Exp. Parasitol. 84:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, T., K. Kawakami, M. H. Qureshi, H. Okamura, M. Kurimoto, and A. Saito. 1997. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-18 synergistically induce the fungicidal activity of murine peritoneal exudate cells against Cryptococcus neoformans through production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells. Infect. Immun. 65:3594-3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]