Abstract

To determine the role of endogenous interleukin-18 (IL-18) during peritonitis, IL-18 gene-deficient (IL-18 KO) mice and wild-type mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) infected with Escherichia coli, the most common causative agent found in septic peritonitis. Peritonitis was associated with a bacterial dose-dependent increase in IL-18 concentrations in peritoneal fluid and plasma. After infection, IL-18 KO mice had significantly more bacteria in the peritoneal lavage fluid and were more susceptible for progression to systemic infection at 6 and 20 h postinoculation than wild-type mice. The relative inability of IL-18 KO mice to clear E. coli from the abdominal cavity was not due to an intrinsic defect in the phagocytosing capacity of their peritoneal macrophages or neutrophils. IL-18 KO mice displayed an increased neutrophil influx into the peritoneal cavity, but these migratory neutrophils were less activate, as reflected by a reduced CD11b surface expression. These data suggest that endogenous IL-18 plays an important role in the early antibacterial host response during E. coli-induced peritonitis.

Despite advances in diagnosis, surgery, antimicrobial therapy, and intensive care support, the mortality rate associated with severe peritonitis remains high (5, 6). In particular, sepsis that originates from the peritoneal cavity has a grim prognosis, with mortality rates up to 80% (13). Escherichia coli is one of the most common causative pathogens (causing up to 60% of cases) in intraperitoneal (i.p.) infections (18).

Cytokines play an important role in the pathogenesis of bacterial infections (32). Local activity of proinflammatory cytokines is required for an adequate antimicrobial defense against localized bacterial infections. On the other hand, systemic activity of proinflammatory cytokines, such as is observed during fulminant sepsis, can be toxic to the host and can contribute to multiple-organ failure and death. Our laboratory recently provided evidence for this dual effect of cytokine activity in a murine model of E. coli peritonitis (28). Indeed, mice deficient for the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 (IL-10) (IL-10 knockout [KO] mice) demonstrated enhanced bacterial clearance from the abdominal cavity and diminished dissemination of the infection to distant organs after i.p. injection of live E. coli. In spite of these findings, systemic inflammation and multiple-organ failure were more prominent in IL-10 KO mice, and the mortality rate was increased.

IL-18 was originally identified as a gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-inducing factor but now is generally recognized as a proinflammatory cytokine (1, 7). IL-18 can induce a wide array of inflammatory responses in different cell types, including activation of nuclear factor κB, Fas ligand expression, and induction of chemokines. It plays an important role in the host response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the toxic component of the gram-negative bacterial cell membrane. In one study, IL-18 KO mice tolerated a 50% higher LPS dose than did wild-type (WT) mice (12), and treatment with an anti-IL-18 antiserum protected mice against the lethal effects of both E. coli and Salmonella LPS (21). Moreover, treatment of mice with a fusion construct consisting of recombinant human IL-18 binding protein and human immunoglobulin G1 Fc also conferred a strong protective effect against death after administration of LPS (9). Only a few investigations have addressed the role of IL-18 in host defense against gram-negative infection in vivo and have demonstrated that passive immunization of mice against IL-18 impaired the host defense against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium or Yersinia enterocolitica (4, 8, 19). The role of endogenous IL-18 in host defense against peritonitis is unknown. Therefore, in the present study we sought to determine the role of IL-18 in the local and systemic host response to abdominal sepsis caused by E. coli by using IL-18 KO mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments. IL-18 KO mice were generated as described previously (30) and were on the C57BL/6 background. Normal C57BL/6 WT mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Horst, The Netherlands). Sex- and age-matched (8- to 12-week-old) mice were used in all experiments.

Induction of peritonitis.

Peritonitis was induced as described previously (28). In brief, E. coli O18:K1 was cultured in Luria-Bertani medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C, harvested at mid-log phase, and washed twice with sterile saline before injection to clear the bacteria of medium. Mice were injected i.p. with 102 to 104 CFU of E. coli O18:K1 in 200 μl of sterile isotonic saline. The inoculum was plated immediately after inoculation on blood agar plates to determine viable counts. Control mice received 200 μl of normal saline.

Reagents.

Rabbit anti-murine IL-18 antiserum, kindly donated by C. Dinarello, was prepared as described previously (10). The anti-IL-18 serum contained <10 pg of endotoxin per ml as determined by the Limulus assay. Anti-IL-18 antiserum (200 μl) was given i.p. 1 h before intraperitoneal administration of bacteria. This dose significantly reduced endotoxin-induced IFN-γ release and mortality in mice (21). Rabbit serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was used as a control. In other experiments, recombinant murine IL-18 (MBL, Naka-ku Nagoya, Japan) in a dose of 0.1 μg/200 μl was given i.p. 1 h before i.p. administration of bacteria. Saline was used as a control.

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

Livers were harvested at 20 h after administration of E. coli or sterile saline (controls), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C. To extract total cellular RNA, lungs from three mice per group were pooled and homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.). Then total RNA was isolated using chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation. The RNA pellet was dissolved in 100 μl of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and quantified by spectrophotometry. Reverse transcription was performed by mixing 2 μg of total cellular RNA with 0.5 μg of oligo(dT) (Life Technologies) in a total volume of 12 μl. The mixture was incubated at 72°C for 10 min. Then 8 μl of a solution containing 4 μl of 5x First Strand buffer (Life Technologies), 10 mM dithiothreitol (Life Technologies), 1.25 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, U.K.), and 100 U of Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) was added, and the mixture was incubated at 42°C for 1 h. Finally, the tubes were heated to 72°C for 10 min, after which 180 μl of H2O was added to the reaction mixture. Samples were stored at −20°C until further use. For PCR, 5 μl of cDNA solution was mixed with 20 μl of a solution containing 1× PCR buffer [67 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 6.7 mM MgCl2, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.67 μg of EDTA, 16.6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2% dimethyl sulfoxide, (Merck, München, Germany), 1.25 μg of bovine serum albumin (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), 0.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.), and 75 ng of sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers specific for IL-18 and β-actin (internal standard)]. The PCR amplifications were performed in a thermocycler (Gene Amp PCR System 9700 [Perkin-Elmer]) under the following conditions: 94°C for 5 min (1 cycle) followed immediately by 95°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min (with different numbers of cycles), and a final extension phase of 72°C for 10 min. For semiquantitative assessment of IL-18 mRNA, different numbers of cycles were used to ensure that amplification occurred in the linear phase. To exclude the possibility of finding differences between tubes as a result of unequal concentrations of cDNA in the PCR mixture, a PCR amplification using β-actin as the internal standard was performed on each sample. β-Actin was found to be linear at 27 amplification cycles, and IL-18 was found to be linear at 29 amplification cycles. The primers used for IL-18 (433 bp) were 5′- ACTGTACAACCGCAGTAATACGG-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGTGAACATTACAGATTTATCCC-3 (antisense), and those used for β-actin (617 bp) were 5′- GTCAGAAGGACTCCTATGTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCTCGTTGCCAATAGTGATG-3′ (antisense). PCR products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Monitoring of mortality and sample harvesting.

Our laboratory previously established that in this model mortality occurs predominantly between 18 and 24 h after the E. coli challenge (28); therefore, mortality was assessed every hour during this period and at 6-h intervals thereafter. In this model, mice surviving for more than 3 days appeared healthy and remained alive for at least 4 weeks (after which they were killed). At the time of sacrifice, mice were first anesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane (Abbott Laboratories Ltd.)-2 liters of O2. A peritoneal lavage was then performed with 5 ml of sterile isotonic saline using an 18-gauge needle, and peritoneal lavage fluid was collected in sterile tubes (Plastipack [Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.]). The recovery of peritoneal fluid was >90% in each experiment and did not differ between groups. After collection of peritoneal fluid, deeper anesthesia was induced by i.p. injection of 0.07 ml of FFM mixture (fentanyl [0.315 mg/ml]-fluanisone [10 mg/ml] [Janssen, Beersen, Belgium], midazolam [5 mg/ml] [Roche, Mijdrecht, The Netherlands]) per g. The abdomen was opened, and blood was drawn from the lower caval vein into a sterile syringe, transferred to tubes containing heparin, and immediately placed on ice. Plasma for these determinations was prepared by centrifugation at 1,400 × g for 10 min at 4°C, after which aliquots were stored at −20°C.

Determination of bacterial outgrowth.

Serial 10-fold dilutions of blood, homogenized liver, and peritoneal lavage fluid were made in sterile saline, and 50-μl volumes were plated onto blood agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2, and CFU were counted after 16 h.

Cell counts and differentials.

Cell counts were determined using a hemacytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, Calif.). Subsequently, peritoneal fluid was centrifuged at 1,400 × g for 10 min; the supernatant was collected in sterile tubes and stored at −20°C until used for determination of cytokines. The pellet was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline to a final concentration of 105 cells/ml, and differential cell counts were done on cytospin preparations stained with a modified Giemsa stain (Diff-Quick, [Dade Behring AG, Düdingen, Switzerland]) as specified by the manufacturer.

FACS analysis.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was used to measure granulocyte activation in peritoneal lavage fluid. The analysis was done by using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson). At least 5,000 cells were analyzed in each sample. Erythrocytes were lysed with ice-cold isotonic NH4Cl solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]) for 10 min. Incubations for FACScan analysis were performed in 96-well V-shaped microtiter plates (Greiner B.V., Alphen a/d Rijn, the Netherlands). For staining, 5 × 105 cells/well were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-Ly-6G (Gr-1) and phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD11b rat anti-mouse monoclonal antibodies (1:100) (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). The appropriate isotype controls (Pharmingen) were included in all experiments. The cells were incubated on ice for 30 min and washed twice with cold FACS buffer (phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 0.01% NaN3, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 0.35 mM EDTA) and resuspended in FACS buffer. Granulocyte CD11b expression was determined by forward-scatter and side-scatter gating and by gating Ly-6G-positive cells. Results are expressed as the mean channel fluorescence of Ly-6G-positive cells.

Phagocytosis.

The uptake of E. coli by peritoneal macrophages and granulocytes was analyzed essentially as described previously (36). Macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavities of untreated mice, and 0.5 × 106 cells/well were cultured overnight at 37°C in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum to allow adherence. The macrophages were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution prior to the addition of labeled bacteria. Peritoneal granulocytes were harvested 5 h after i.p. injection of 10% (wt/vol.) proteose peptone (Becton Dickinson) (34). Peritoneal exudate cells were treated with 160 mM NH4Cl-10 mM KHCO3 to lyse erythrocytes, washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution, and plated at 0.5 × 106 cells/well. E. coli was heat-killed by incubation at 65°C for 1 h and labeled with 0.2 mg of FITC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 9.0) for 1 h at 37°C. FITC-labeled E. coli cells (equivalent to 50 × 106 CFU) were added to the cells (bacterium/cell ratio of 100:1) and incubated for 1 h (granulocytes) or 2 h (macrophages) at 37 or 4°C, respectively. Phagocytosis was stopped by immediately transferring the cells to 4°C and washing them with ice-cold FACS buffer. The cells were treated with vital blue stain (Orpegen, Heidelberg, Germany) to quench extracellular fluorescence, washed with FACS buffer, and analyzed using a flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson FACScalibur). Macrophages and granulocytes were gated based on forward and side scatter of light. Based on this selection criterion, the purity of the macrophages and neutrophils was >95%. Results are expressed as phagocytosis index, defined as the percentage of cells with internalized E. coli times the mean fluorescence intensity.

Assays.

IL-18, IL-12, IFN-γ, and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), and keratinocyte-derived cytokine (KC) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays as specified by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom). Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were determined with commercially available kits (Sigma), using a Hitachi analyzer (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) as specified by the manufacturer's instructions.

Histological testing.

Directly after sacrifice, samples from the liver and lungs were fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin for routine histological testing. Sections 4 μm thick were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. All slides were coded and scored by a pathologist without knowledge of the type of mice or treatment used.

Statistical analysis.

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error. Differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Survival was analyzed with Kaplan-Meier. Values of P of <0.05 were considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Production of IL-18.

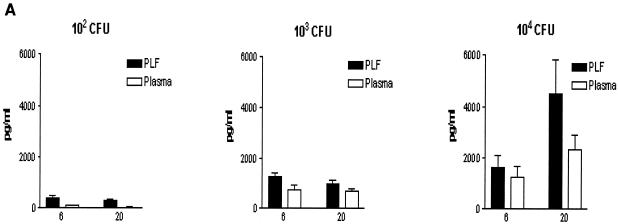

To determine whether IL-18 is produced during peritonitis, WT mice received an i.p. injection with 200 μl of NaCl containing 102, 103, or 104 CFU of E. coli or 200 μl of NaCl as a control. Peritonitis was associated with elevated IL-18 concentrations in both peritoneal fluid and plasma at 6 and 20 h after infection (Fig. 1A). IL-18 levels increased with increasing doses of E. coli and were higher in peritoneal fluid than in plasma. After inoculation with 102 CFU of E. coli, IL-18 levels peaked at 6 h, while after infection with 104 CFU of E. coli, IL-18 levels peaked after 20 h. Mice injected i.p. with sterile saline did not have detectable IL-18 in their peritoneal lavage fluid or plasma (data not shown). In IL-18 KO mice, IL-18 was undetectable at all time points. To determine whether IL-18 mRNA is also produced during E. coli peritonitis, RT-PCR was performed on liver samples obtained from mice 20 h after i.p. administration of saline or E. coli. A faint band of IL-18 mRNA was found in the livers of mice that received saline, indicating that some IL-18 mRNA is constitutively expressed (Fig. 1B). i.p. infection with E. coli was associated with enhanced expression of IL-18 mRNA, as indicated by equal intensity of β-actin bands and clear differences in band intensity between control and peritonitis samples for IL-18 RT-PCR products.

FIG. 1.

Enhanced IL-18 production during peritonitis. (A). IL-18 levels, measured by ELISA, in peritoneal lavage fluid (PLF) and plasma. WT mice were injected i.p. with 200 μl containing 102, 103, and 104 CFU of E. coli and sacrificed after 6 and 20 h. Results are expressed as mean and standard error of the mean for eight mice per group. (B). IL-18 mRNA and β-actin mRNA expression in the liver as determined by RT-PCR at 20 h after i.p. injection of sterile saline or 104 CFU of E. coli. Livers from three mice per group were pooled.

IL-18 KO mice show an increased bacterial outgrowth.

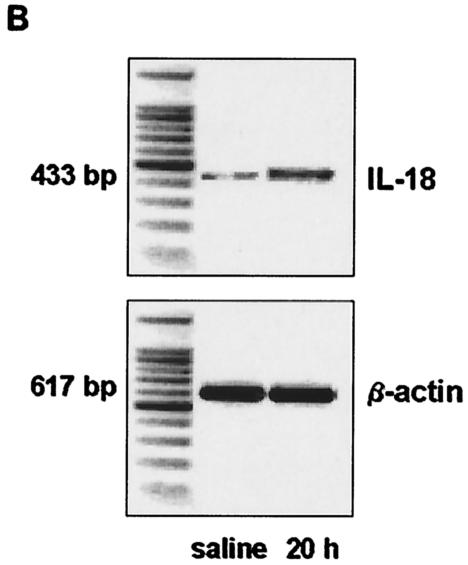

To determine the role of IL-18 in early host defense against peritonitis, we compared the bacterial outgrowth in peritoneal lavage fluid (the site of the infection), blood (to evaluate to which extent the infection became systemic), and livers of WT and IL-18 KO mice after i.p. inoculation with 104 CFU of E. coli (Fig. 2). At both 6 and 20 h postinfection, IL-18 KO mice had more bacteria in the peritoneal lavage fluid and blood than did the WT mice (P < 0.05). In addition, the livers of IL-18 KO mice contained more bacteria than did those of WT mice, although at 20 h postinfection the difference between the two strains did not reach statistical significance. Hence, IL-18 KO mice demonstrated a reduced capacity to clear E. coli from the primary infectious site in association with an enhanced dissemination of the infection.

FIG. 2.

IL-18 KO mice demonstrate enhanced bacterial outgrowth. The E. coli cell count in peritoneal lavage fluid (top panel), blood (middle panel), and liver (bottom panel) in IL-18 KO and WT mice 6 and 20 h after i.p. administration of 104 CFU of E. coli is shown. Solid symbols represent WT mice; open symbols represent IL-18 KO mice. Horizontal lines represent medians. *, P < 0.05 for the difference between groups.

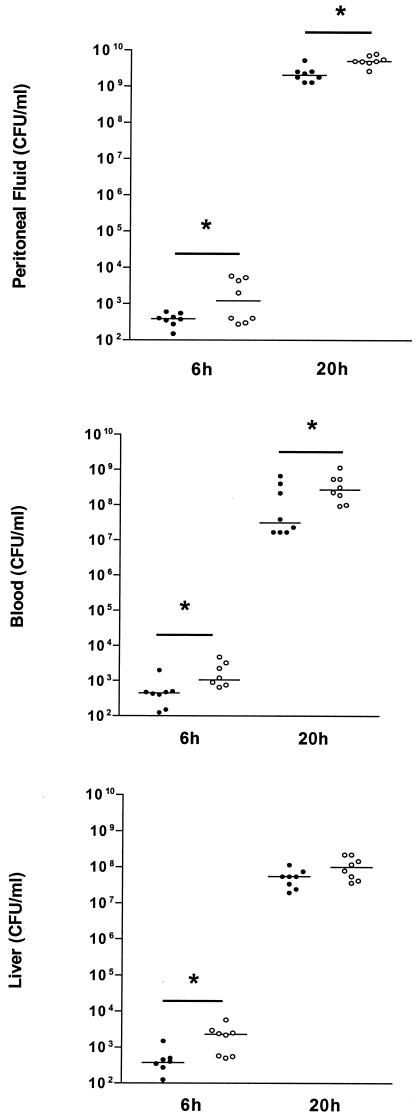

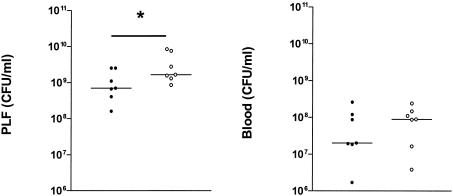

Treatment of WT mice with anti-IL-18 and recombinant murine IL-18.

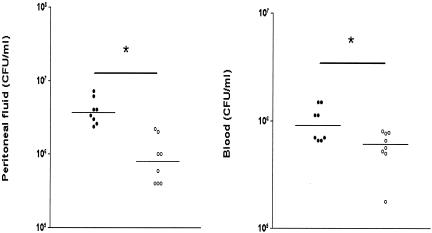

Compensatory immune mechanisms may develop in mice that genetically lack the IL-18 signaling pathway. To determine whether the differences between IL-18 KO and WT mice were caused solely by the absence of IL-18, WT mice were treated with an anti-IL-18 antibody or normal rabbit serum 1 h prior to i.p. infection with E. coli (Fig. 3). The results of the experiments with IL-18 KO mice could be replicated in this experiment, i.e., treatment with anti-IL-18 was associated with increased CFU numbers in peritoneal lavage fluid and blood at 20 h postinfection (P < 0.05 versus controls for peritoneal lavage fluid). To obtain further evidence for an antibacterial effect of IL-18 during E. coli peritonitis, we injected mice i.p. with recombinant murine IL-18 (0.1 μg) 1 h prior to infection and determined the CFU count 20 h after the bacterial challenge (Fig. 4). IL-18-treated mice displayed a decreased outgrowth in both peritoneal lavage fluid and blood (P < 0.05 versus controls).

FIG. 3.

Anti-IL-18 treatment increases bacterial outgrowth. The E. coli cell count in peritoneal lavage fluid (left) and blood (right) in WT mice 20 h after i.p. administration of 104 CFU of E. coli is shown. At 1 h prior to infection, mice received either rabbit anti-IL-18 serum (200 μl) (open symbols) or normal rabbit serum (control) (solid symbols). Horizontal lines represent medians. *, P < 0.05 for the difference between groups.

FIG. 4.

Recombinant IL-18 inhibits bacterial outgrowth. The E. coli cell count in peritoneal lavage fluid (left) and blood (right) in WT mice 20 h after i.p. administration of 104 CFU of E. coli is shown. At 1 h prior to infection, mice received either 0.1 μg of recombinant mouse IL-18 (open symbols) or saline (control) (solid symbols). Horizontal lines represent medians. *, P < 0.05 for the difference between groups.

IL-18 KO mice have an increased neutrophil recruitment to the peritoneal cavity.

Since leukocytes play an important role in the local host defense against invading bacteria, we next determined leukocyte counts and differentials in peritoneal lavage fluid during peritonitis. Peritonitis was associated with a profound influx of cells into the peritoneal cavity, which was mainly the result of neutrophil influx (Table 1). IL-18 KO mice had more neutrophils in their peritoneal fluid than did WT mice at both 6 and 20 h postinfection (P < 0.05).

TABLE 1.

IL-18 KO mice have an increased granulocyte influx into the peritoneal fluid during peritonitisa

| Cell type | Cell counts in peritoneal fluid at time:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h

|

6 h

|

20 h

|

||||

| WT (104/ml) | KO (104/ml) | WT (106/ml) | KO (106/ml) | WT (106/ml) | KO (106/ml) | |

| Total cells | 15 ± 0.1 | 14.2 ± 0.2 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | 11.2 ± 2.4* | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.9* |

| Neutrophils | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | 7.9 ± 1.4* | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 3.9 ± 0.6* |

| Macrophages | 14.0 ± 0.6 | 13.1 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

| Other | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

Mice were sacrificed at 0, 6, and 20 h after i.p. administration of 104 CFU of E. coli to obtain peritoneal lavage fluid. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Note that cell counts are given as 104/ml at t = 0 and as 106/ml at t = 6 and 20 h. Each group consisted of eight mice for each time point, except the t = 0 group (five mice). *, P < 0.05 versus WT mice.

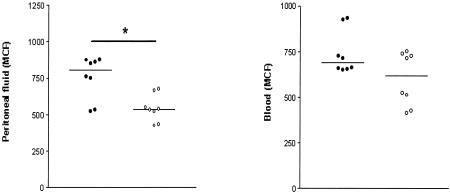

IL-18 KO mice have a reduced CD11b expression on peritoneal neutrophils.

The extent of CD11b expression at the surface of neutrophils has been used as an activation marker of this cell type (17, 25, 33). Since IL-18 is able to activate neutrophils in vitro, which includes upregulation of CD11b (17), we considered it of interest to compare neutrophil CD11b expression at the site of infection in IL-18 KO and WT mice (Fig. 5). Neutrophils derived from peritoneal fluid of IL-18 KO mice obtained 20 h after infection expressed less CD11b at their surface than did neutrophils from peritoneal fluid of WT mice (P < 0.05).

FIG. 5.

IL-18 KO mice have a decreased CD11b expression on peritoneal neutrophils. CD11b expression (mean channel fluorescence [MCF]) was determined by FACS analysis of neutrophils harvested from peritoneal fluid at 20 h postinfection, as described in Materials and Methods. Solid symbols represent WT mice; open symbols indicate IL-18 KO mice. Horizontal lines represent medians. *, P < 0.05 for the difference between groups.

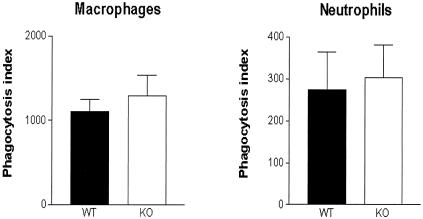

Unchanged phagocytosis of E. coli by IL-18-deficient peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages.

The increased bacterial load in IL-18 KO mice could be caused by an intrinsic defect in the ability of IL-18-deficient cells to phagocytose E. coli. To investigate this possibility, we harvested neutrophils and macrophages from uninfected IL-18 KO and WT mice and compared their capacity to phagocytose FITC-labeled E. coli (Fig. 6). Both peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages from the IL-18 KO mice displayed a normal ability to phagocytose E. coli.

FIG. 6.

Phagocytosis of E. coli by peritoneal macrophages and neutrophils of IL-18 KO mice is unchanged with respect to WT. Phagocytosis of FITC-labeled E. coli by macrophages and granulocytes harvested from peritoneal fluid from uninfected mice was determined by FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Solid bars represent WT mice; open bars represent IL-18 KO mice. Results (mean and standard error) are expressed as the phagocytosis index, defined as the percentage of cells with internalized E. coli multiplied by the mean fluorescence intensity.

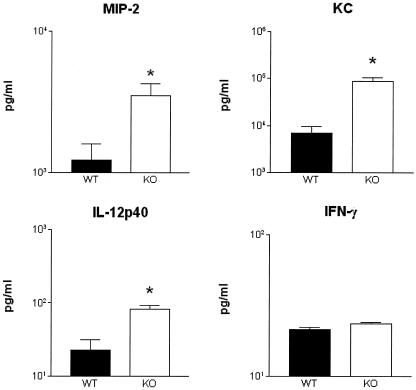

Chemokine and cytokine response.

The mouse CXC chemokines MIP-2 and KC have been implicated in the attraction of neutrophils to the site of an infection (23, 35). Therefore, the concentrations of these mediators were measured in peritoneal fluid (Fig. 7). IL-18 KO mice had higher concentrations of both MIP-2 and KC at the site of the infection than did WT mice (P < 0.05). In addition, since IL-18, together with IL-12, is required for optimal induction of IFN-γ (1, 7), the levels of IL-12 and IFN-γ were measured in peritoneal fluid (Fig. 7). Whereas IL-12 concentrations were higher in IL-18 KO mice than in WT mice (P < 0.05), IFN-γ levels did not differ between IL-18 KO and WT mice.

FIG. 7.

Chemokine and cytokine concentrations in peritoneal lavage fluid. MIP-2, KC, IL-12p40 and IFN-γ concentrations in peritoneal lavage fluid obtained 20 h postinfection are shown. Solid bars represent WT mice; open bars represent IL-18 KO mice. Data are the mean and standard error for eight mice per strain. *, P < 0.05 versus WT mice.

IL-18 KO mice demonstrate enhanced lung and liver injury.

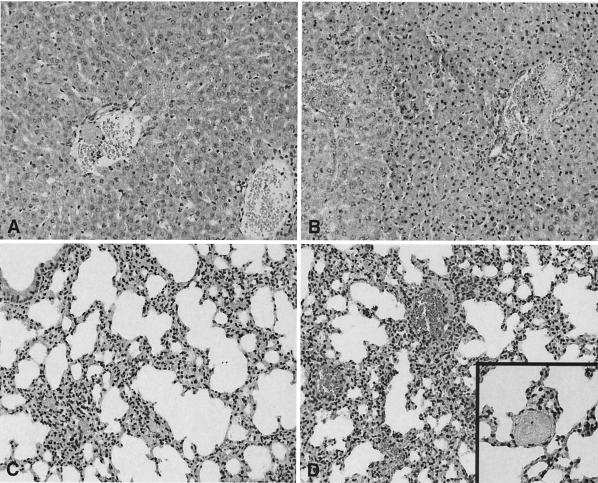

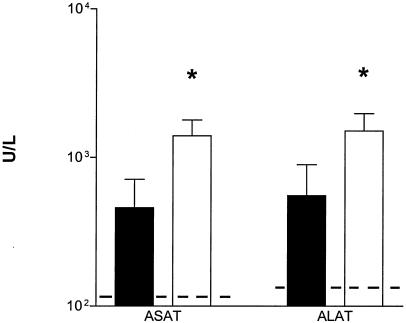

To evaluate the role of endogenous IL-18 in organ injury during abdominal sepsis, we performed a histological analysis of liver and lungs stained 20 h after infection. As shown in Fig. 8, IL-18 KO mice displayed more severe liver and lung damage than did WT mice. The lungs of both mouse strains displayed congestion and interstitial inflammation. These changes were more severe in IL-18 KO mice (Fig. 8D), than in WT mice (Fig. 8C). Moreover, in IL-18 KO mice, small thrombi were seen (Fig. 8D inset), as well as foci of pleuritis (data not shown). In the livers of IL-18 KO mice, numerous thrombi were observed (Fig. 8B). These changes were more pronounced in the livers of IL-18 KO mice than in those of WT mice (Fig. 8A). The histopathological findings in the livers were confirmed by clinical chemistry; i.e., IL-18 KO mice had higher concentrations of ALT and AST in plasma 20 h postinfection than did WT mice (both P < 0.05) (Fig. 9).

FIG. 8.

IL-18 KO mice demonstrate increased liver and lung injury. Representative views of the histological damage in the livers (A and B) and lungs (C and D) of WT mice (A and C) and IL-18 KO mice (B and D) at 20 h after infection are shown. Liver necrosis was more extended in IL-18 KO mice than in WT mice. The lungs of IL-18 KO mice were also more inflamed than those of WT mice. Numerous thrombi were observed (inset in panel D). The illustrations shown are representative of a total of eight mice per group. Hematoxylin and eosin staining. Magnification, ×20 (A to D) and ×40 (inset in panel D).

FIG. 9.

IL-18 KO mice demonstrate enhanced hepatocellular injury. Concentrations of ALT and AST in plasma (units/liter) at 20 h after i.p. injection of E. coli (104 CFU) are shown. Solid bars represent WT mice; open bars represent IL-18 KO mice. Data are the mean and standard error for eight mice per strain. Dotted lines represent the mean values obtained from normal plasma of mice that were injected i.p. with sterile saline (six mice). *, P < 0.05 versus WT mice.

Survival.

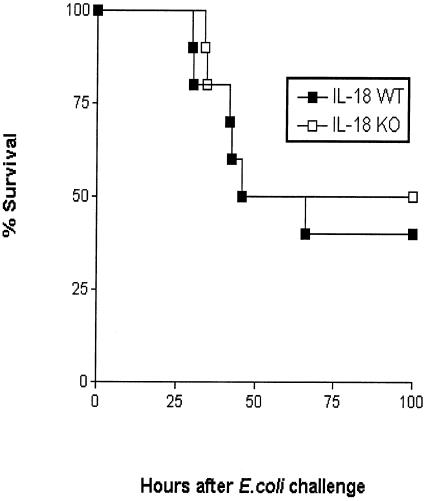

To determine the influence of IL-18 on survival, IL-18 KO and WT mice were infected with 104 CFU of E. coli and observed for 4 days (Fig. 10). Survival did not differ between the two mouse strains.

FIG. 10.

IL-18 deficiency does not influence survival during murine peritonitis. Survival of WT and IL-18 KO mice infected i.p. with E. coli (104 CFU; n = 10 per group). No difference was found between the mortality rate in the two mouse strains.

DISCUSSION

Severe bacterial infection is associated with enhanced production of IL-18, as reflected by elevated circulating levels of this proinflammatory cytokine in patients with sepsis (11, 16, 22). In experimental animals, several organs express IL-18 constitutively, especially the liver and lungs, and an increase in the concentrations of IL-18 in plasma was detected after administration of high doses of LPS (3, 14, 21). In the present investigation, we sought to determine the extent of IL-18 production during abdominal sepsis caused by E. coli and the role of this endogenously produced IL-18 in the host response to this infection. We confirmed the presence of constitutive expression of IL-18 mRNA in the liver and demonstrated bacterial dose-dependent release of IL-18 in peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma. In addition, IL-18 KO mice were less able to clear bacteria from the site of infection and showed an increased dissemination of the infection to the blood compartment, indicating that IL-18 plays an important regulatory role in the early local antimicrobial host defense against E. coli.

Peritonitis is characterized by the recruitment of phagocytic cells, especially neutrophils, to the site of infection (28, 35). Neutrophil influx into the peritoneal cavity was markedly increased in IL-18 KO mice 6 and 20 h after E. coli administration. This finding was unexpected in light of a previous investigation that showed enhanced influx of neutrophils into the peritoneal fluid of mice injected i.p. with recombinant IL-18 (17). The most likely explanation for the increased peritoneal neutrophil numbers in IL-18 KO mice is that they are a consequence of the increased proinflammatory stimulus provided by the higher bacterial load. Theoretically, the increased recruitment of neutrophils to the peritoneal fluid of IL-18 KO mice may also have been mediated in part by the elevated local concentrations of the CXC chemokines MIP-2 and KC, which are known to contribute to neutrophil attraction to sites of bacterial infection (23, 35). The elevated MIP-2 and KC concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of IL-18 KO mice were probably also a consequence of the enhanced outgrowth of E. coli, especially considering that in contrast to our study with living bacteria, treatment of mice with anti-IL-18 antibodies before challenge with E. coli LPS was accompanied by a significant decrease in MIP-2 levels and diminished neutrophil accumulation in the lungs and liver (21). Furthermore, IL-18 has been reported to increase rather than inhibit the production of IL-8, the prototypic human CXC chemokine, in vitro (17, 24).

A recent study identified a role for IL-18 in the activation of neutrophils (17). IL-18 induced the release of cytokines and chemokines from human peripheral blood-derived neutrophils, induced degranulation, enhanced the respiratory burst after stimulation with formylmethionine-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP) and upregulated the surface expression of the activation marker CD11b. We here demonstrate that endogenous IL-18 plays a role in the activation of neutrophils recruited to the peritoneal cavity during E. coli peritonitis. Indeed, IL-18 KO mice displayed a reduced expression of CD11b at the surface of neutrophils recovered from their peritoneal fluid. These data are the first to indicate that IL-18 may contribute to neutrophil activation during infection in vivo.

IL-18 has been implicated, together with IL-12, in optimal production of IFN-γ (1, 7). IL-18 in particular seems important for IFN-γ production induced by a gram-negative bacterial stimulus such as LPS. Indeed, elimination of endogenous IL-18 decreased IFN-γ release in mice during endotoxemia (9, 12, 21), whereas IL-18 did not contribute to IFN-γ release after administration of the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B to mice (12, 15). Although IFN-γ concentrations in peritoneal fluid did not differ between IL-18 KO and WT mice, it is possible that the higher bacterial load in the former mouse strain compensated for the IL-18 deficiency and that IL-18 does play a role in IFN-γ production during gram-negative bacterial infection.

IL-18 KO mice displayed more signs of lung and liver injury than did WT mice. The increased bacterial loads in these mice probably played an important role in this injury. Indeed, passive immunization against IL-18 diminished systemic inflammation elicited by LPS (21). Moreover, Propionibacterium acnes-primed IL-18 KO mice are resistant to LPS-induced liver injury (26).

IL-18 exerts cellular effects by undergoing a specific interaction with the IL-18 receptor complex, consisting of a high-affinity ligand binding chain (IL-18R or IL-18Rα) and a signal-transducing element (IL-18R accessory protein or IL-18Rβ) (29). The intracellular signaling cascade induced after triggering of the IL-18R complex is highly similar to the signaling cascades induced after stimulation of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family. Indeed, these distinct receptors all use the same intracellular adapter molecules (MyD88, IRAK, and TRAF6) and elicit similar responses (activation of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [2, 29, 31]). In this respect, it is interesting that MyD88 gene-deficient mice were reported to have a normal capacity to clear bacteria from their peritoneal cavity after induction of peritonitis induced by placing a stent in the colon ascendens (37). However, MyD88 KO mice displayed an enhanced survival in this abdominal sepsis model, presumably due to a relatively attenuated systemic inflammatory response. In contrast, mice lacking TLR4, the receptor considered to be essential for the recognition of LPS and gram-negative bacteria, did not demonstrate an altered survival (37). Several non-mutually exclusive possibilities may explain these observations on the role of IL-18, TLR4, and MyD88 in abdominal sepsis, including differences in the models used, in the extent and localization of IL-18 production, and in the cellular and tissue distribution of the IL-18R, TLR4, and MyD88.

Previous investigations have addressed the role of IL-18 in host defense against gram-negative bacterial infection in vivo. Administration anti-IL-18 to mice intravenously infected with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium was associated with a relatively enhanced outgrowth of bacteria in the liver and spleen seven days after the infection (19). In line with these findings, anti-IL-18 treatment increased bacterial growth in the spleens of mice intravenously infected with Y. enterocolitica and IL-18 KO mice demonstrated a higher bacterial load in their lungs after intranasal infection with Shigella flexneri (4, 27). IL-18 also contributes to an effective host defense against gram-positive bacterial infection, including systemic infection with Listeria monocytogenes and pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (14, 20). The present investigation provides the first evidence for a role for IL-18 in the early antibacterial defense against i.p. infection, as indicated by the fact that IL-18 KO mice had a reduced ability to clear E. coli from their peritoneal cavity and were less capable of preventing dissemination of the infection. This finding was supported by the fact that exogenous treatment with recombinant IL-18 facilitated antibacterial defense in this model. Notably, similar and even higher doses of recombinant IL-18 did not influence the outgrowth of Y. enterocolitica in an intravenous-infection model (4) whereas daily treatment with IL-18 starting 2 days before intravenous infection with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium did reduce bacterial counts in the liver and spleen (19). In our study, IL-18 deficiency did not affect survival. We recently reported similar findings for pneumococcal pneumonia; i.e., in that model, IL-18 KO mice also demonstrated an increased bacterial outgrowth yet did not have a reduced survival (14). Together, these data suggest that IL-18 in particular contributes to the early host response to bacterial infection.

The present study indicates that IL-18 is produced at the site of infection during experimentally induced E. coli peritonitis, where it facilitates an optimal host response by limiting the bacterial outgrowth and thereby reducing secondary tissue injury. Thus, IL-18 production is part of a protective early immune response to abdominal sepsis caused by E. coli.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Society of Scientific Research (NWO) to S. Weijer.

We thank Ingvild Kopp and Joost Daalhuijsen for expert technical assistance and C. Dinarello for his kind gift of rabbit anti-mouse IL-18 antiserum.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Akira, S. 2000. The role of IL-18 in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 12:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira, S. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Adv. Immunol. 78:1-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndt, P. G., G. Fantuzzi, and E. Abraham. 2000. Expression of interleukin-18 in the lung after endotoxemia or hemorrhage-induced acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 22:708-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bohn, E., A. Sing, R. Zumbihl, C. Bielfeldt, H. Okamura, M. Kurimoto, J. Heesemann, and I. B. Autenrieth. 1998. IL-18 (IFN-gamma-inducing factor) regulates early cytokine production in, and promotes resolution of, bacterial infection in mice. J. Immunol. 160:299-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosscha, K., K. Reijnders, P. F. Hulstaert, A. Algra, and C. van der Werken. 1997. Prognostic scoring systems to predict outcome in peritonitis and intra-abdominal sepsis. Br. J. Surg. 84:1532-1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christou, N. V., P. S. Barie, E. P. Dellinger, J. P. Waymack, and H. H. Stone. 1993. Surgical Infection Society intra-abdominal infection study. Prospective evaluation of management techniques and outcome Arch. Surg. 128:193-198; discussion, 198-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinarello, C. A. 2000. Interleukin-18, a proinflammatory cytokine. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 11:483-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dybing, J. K., N. Walters, and D. W. Pascual. 1999. Role of endogenous interleukin-18 in resolving wild-type and attenuated Salmonella typhimurium infections. Infect. Immun. 67:6242-6248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faggioni, R., R. C. Cattley, J. Guo, S. Flores, H. Brown, M. Qi, S. Yin, D. Hill, S. Scully, C. Chen, D. Brankow, J. Lewis, C. Baikalov, H. Yamane, T. Meng, F. Martin, S. Hu, T. Boone, and G. Senaldi. 2001. IL-18-binding protein protects against lipopolysaccharide- induced lethality and prevents the development of Fas/Fas ligand-mediated models of liver disease in mice. J. Immunol. 167:5913-5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fantuzzi, G., A. J. Puren, M. W. Harding, D. J. Livingston, and C. A. Dinarello. 1998. Interleukin-18 regulation of interferon gamma production and cell proliferation as shown in interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme (caspase-1)-deficient mice. Blood 91:2118-2125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grobmyer, S. R., E. Lin, S. F. Lowry, D. E. Rivadeneira, S. Potter, P. S. Barie, and C. F. Nathan. 2000. Elevation of IL-18 in human sepsis. J. Clin. Immunol. 20:212-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochholzer, P., G. B. Lipford, H. Wagner, K. Pfeffer, and K. Heeg. 2000. Role of interleukin-18 (IL-18) during lethal shock: decreased lipopolysaccharide sensitivity but normal superantigen reaction in IL-18-deficient mice. Infect. Immun. 68:3502-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holzheimer, R. G., K. H. Muhrer, N. L'Allemand, T. Schmidt, and K. Henneking. 1991. Intraabdominal infections: classification, mortality, scoring and pathophysiology. Infection 19:447-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauw, F. N., J. Branger, S. Florquin, P. Speelman, S. J. van Deventer, S. Akira, and T. van der Poll. 2002. IL-18 improves the early antimicrobial host response to pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Immunol. 168:372-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauw, F. N., S. Florquin, P. Speelman, S. J. van Deventer, and T. van der Poll. 2001. Role of endogenous interleukin-12 in immune response to staphylococcal enterotoxin B in mice. Infect. Immun. 69:5949-5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauw, F. N., A. J. Simpson, J. M. Prins, M. D. Smith, M. Kurimoto, S. J. van Deventer, P. Speelman, W. Chaowagul, N. J. White, and T. van der Poll. 1999. Elevated plasma concentrations of interferon (IFN)-gamma and the IFN-gamma-inducing cytokines interleukin (IL)-18, IL-12, and IL-15 in severe melioidosis. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1878-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung, B. P., S. Culshaw, J. A. Gracie, D. Hunter, C. A. Canetti, C. Campbell, F. Cunha, F. Y. Liew, and I. B. McInnes. 2001. A role for IL-18 in neutrophil activation. J. Immunol. 167:2879-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorber, B., and R. M. Swenson. 1975. The bacteriology of intra-abdominal infections. Surg. Clin. North Am. 55:1349-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mastroeni, P., S. Clare, S. Khan, J. A. Harrison, C. E. Hormaeche, H. Okamura, M. Kurimoto, and G. Dougan. 1999. Interleukin 18 contributes to host resistance and gamma interferon production in mice infected with virulent Salmonella typhimurium Infect. Immun. 67:478-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neighbors, M., X. Xu, F. J. Barrat, S. R. Ruuls, T. Churakova, R. Debets, J. F. Bazan, R. A. Kastelein, J. S. Abrams, and A. O'Garra. 2001. A critical role for interleukin 18 in primary and memory effector responses to Listeria monocytogenes that extends beyond its effects on interferon gamma production. J. Exp. Med. 194:343-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Netea, M. G., G. Fantuzzi, B. J. Kullberg, R. J. Stuyt, E. J. Pulido, R. C. McIntyre, Jr., L. A. Joosten, J. W. Van der Meer, and C. A. Dinarello. 2000. Neutralization of IL-18 reduces neutrophil tissue accumulation and protects mice against lethal Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium endotoxemia. J. Immunol. 164:2644-2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novick, D., B. Schwartsburd, R. Pinkus, D. Suissa, I. Belzer, Z. Sthoeger, W. F. Keane, Y. Chvatchko, S. H. Kim, G. Fantuzzi, C. A. Dinarello, and M. Rubinstein. 2001. A novel IL-18BP ELISA shows elevated serum IL-18BP in sepsis and extensive decrease of free IL-18. Cytokin. 14:334-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson, T. S., and K. Ley. 2002. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in leukocyte trafficking. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 283:R7-R28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puren, A. J., G. Fantuzzi, Y. Gu, M. S. Su, and C. A. Dinarello. 1998. Interleukin-18 (IFNgamma-inducing factor) induces IL-8 and IL-1beta via TNFalpha production from non-CD14+ human blood mononuclear cells. J. Clin. Investig. 101:711-721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rijneveld, A. W., F. N. Lauw, M. J. Schultz, S. Florquin, A. A. Te Velde, P. Speelman, S. J. Van Deventer, and T. Van Der Poll. 2002. The role of interferon-gamma in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 185:91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakao, Y., K. Takeda, H. Tsutsui, T. Kaisho, F. Nomura, H. Okamura, K. Nakanishi, and S. Akira. 1999. IL-18-deficient mice are resistant to endotoxin-induced liver injury but highly susceptible to endotoxin shock. Int. Immunol. 11:471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sansonetti, P. J., A. Phalipon, J. Arondel, K. Thirumalai, S. Banerjee, S. Akira, K. Takeda, and A. Zychlinsky. 2000. Caspase-1 activation of IL-1beta and IL-18 are essential for Shigella flexneri-induced inflammation. Immunity 12:581-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sewnath, M. E., D. P. Olszyna, R. Birjmohun, F. J. ten Kate, D. J. Gouma, and T. van Der Poll. 2001. IL-10-deficient mice demonstrate multiple organ failure and increased mortality during Escherichia coli peritonitis despite an accelerated bacterial clearance. J. Immunol. 166:6323-6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sims, J. E. 2002. IL-1 and IL-18 receptors, and their extended family. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:117-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda, K., H. Tsutsui, T. Yoshimoto, O. Adachi, N. Yoshida, T. Kishimoto, H. Okamura, K. Nakanishi, and S. Akira. 1998. Defective NK cell activity and Th1 response in IL-18-deficient mice. Immunity 8:383-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomassen, E., T. A. Bird, B. R. Renshaw, M. K. Kennedy, and J. E. Sims. 1998. Binding of interleukin-18 to the interleukin-1 receptor homologous receptor IL-1Rrp1 leads to activation of signaling pathways similar to those used by interleukin-1. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 18:1077-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van der Poll, T. 2001. Immunotherapy of sepsis. Lancet Infect Dis. 1:165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verbon, A., P. E. Dekkers, T. ten Hove, C. E. Hack, J. P. Pribble, T. Turner, S. Souza, T. Axtelle, F. J. Hoek, S. J. van Deventer, and T. van der Poll. 2001. IC14, an anti-CD14 antibody, inhibits endotoxin-mediated symptoms and inflammatory responses in humans. J. Immunol. 166:3599-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vonk, A. G., C. W. Wieland, M. G. Netea, and B. J. Kullberg. 2002. Phagocytosis and intracellular killing of Candida albicans blastoconidia by neutrophils and macrophages: a comparison of different microbiological test systems. J. Microbiol. Methods 49:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walley, K. R., N. W. Lukacs, T. J. Standiford, R. M. Strieter, and S. L. Kunkel. 1997. Elevated levels of macrophage inflammatory protein 2 in severe murine peritonitis increase neutrophil recruitment and mortality. Infect. Immun. 65:3847-3851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wan, C. P., C. S. Park, and B. H. Lau. 1993. A rapid and simple microfluorometric phagocytosis assay. J. Immunol. Methods 162:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weighardt, H., S. Kaiser-Moore, R. M. Vabulas, C. J. Kirschning, H. Wagner, and B. Holzmann. 2002. Cutting edge: myeloid differentiation factor 88 deficiency improves resistance against sepsis caused by polymicrobial infection. J. Immunol. 169:2823-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]