Abstract

gp63 is a highly abundant glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein expressed predominantly in the promastigote but also in the amastigote stage of Leishmania species. In Leishmania spp., gp63 has been implicated in a number of steps in establishment of infection. Here we demonstrate that Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiological agent of Chagas' disease, has a family of gp63 genes composed of multiple groups. Two of these groups, Tcgp63-I and -II, are present as high-copy-number genes. The genomic organization and mRNA expression pattern were specific for each group. Tcgp63-I was widely expressed, while the Tcgp63-II group was scarcely detected in Northern blots, even though it is well represented in the T. cruzi genome. Western blots using sera directed against a synthetic peptide indicated that the Tcgp63-I group produced proteins of ∼78 kDa, differentially expressed during the life cycle. Immunofluorescence staining and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C digestion confirmed that Tcgp63-I group members are surface proteins bound to the membrane by a GPI anchor. We also demonstrate the presence of metalloprotease activity which is attributable, at least in part, to Tcgp63-I group. Since antibodies against Tcgp63-I partially blocked infection of Vero cells by trypomastigotes, a possible role for this group in infection is suggested.

Trypanosoma cruzi is the flagellated protozoan parasite that causes American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas' disease), a chronic illness prevalent in Latin America (55). This parasite has a complex life cycle, involving a hematophagous insect vector and a mammalian host. It has an obligate intracellular replicative form, the amastigote, and a nonreplicative one, the bloodstream trypomastigote, within the mammalian host. The major forms present in the insect vector are also a replicative form, the epimastigote, and a nonreplicative one, the infective metacyclic trypomastigote.

The proteases present in different protozoan parasites appear to be relevant for several aspects of host-parasite interactions, quite apart from their obvious participation in the nutrition of the parasite at the expense of the host. Metalloproteases have been described in a number of parasites, but only that present in Leishmania spp. has been thoroughly characterized (6).

Leishmania spp. are parasitic protozoa that alternate between a promastigote form in the insect vector and an amastigote form in the vertebrate host. At their surfaces, Leishmania spp. express a major glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoprotein of 63 kDa named gp63 or leishmanolysin, which represents more than 1% of the total cell protein (5, 18). gp63 is a Zn2+-dependent HEXXH metalloprotease with a broad range of substrate specificity and optimum pH activity (7). The protease is produced as a proenzyme (30) that is N glycosylated (32). The genes that code for gp63 in Leishmania are clustered in tandem repeats, usually located on a single chromosome, and can be divided in classes according to their expression pattern during the development of the parasite (9, 40). gp63s are abundantly expressed on the surface of the promastigote form, are upregulated in infectious metacyclic promastigotes, and have a low but detectable expression level in the intracellular amastigote stage (34, 46).

gp63 plays different roles in the host-parasite interactions and has been postulated as a virulence factor (27). A role for gp63 in the attachment of the promastigote form to host cell surface receptors, such as the fibronectin receptor, has been suggested (11, 43, 48). In addition, it interacts with the complement system (42) and may contribute to the ability of the amastigote form of Leishmania spp. to survive inside the macrophage (12, 31, 47). It was also suggested that the primary role of the proteolytic activity of gp63 is related to the cleavage of host cell macromolecules, either for protection or to provide parasite nutrition (12). Its predominant expression in the promastigote form, together with the identification of homologues in monogenetic trypanosomatids like Crithidia fasciculata and Herpetomonas samuelpessoai (26, 45), suggest that leishmanolysin may be important for the interaction with the invertebrate host. However, gp63 is apparently not essential for insect stages of the life cycle, as Leishmania major promastigote-specific genes can be deleted without deleterious effects on growth and development in the sandfly vector (27).

There is evidence for both zinc metalloprotease activities and gp63 gene homologues in African trypanosomes (2, 15). RNAi experiments recently performed on T. brucei indicated that at least one of these homologues provides the previously detected zinc metalloprotease activity (28). In T. cruzi, different metalloprotease activities were previously described (23), some of them specifically expressed during metacyclogenesis (3, 29), but there is no evidence about their possible relationship to Leishmania gp63. Four gp63-homologous genes in T. cruzi, some of them predominantly expressed at mRNA level in the amastigote stage, have been identified (22).

We report in this paper that gp63 in T. cruzi, like in Leishmania spp., is present as a family of multiple genes with at least two groups, whose expression is regulated during parasite differentiation. At least one of the members of the Tcgp63-I group presents metalloprotease activity and is bound to the parasite's membrane by a GPI anchor. We discuss the possible role of Tcgp63-I in infection of mammalian host cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite cultures.

T. cruzi CL Brener cloned stock was used (56) for parasite culture. Different forms of the parasite were obtained as previously described (20). Other parasites used in this study were Tulahuen2 and Y strains as well as SylvioX10 and CA-I/72 cloned stocks. Purity of the different forms of the parasite (epimastigote, metacyclic trypomastigote, cell-derived trypomastigote, and amastigote) was examined by conventional microscopy and was at least 95%.

Nucleic acids purification.

DNA was prepared from epimastigotes of T. cruzi by using conventional Proteinase K phenol-chloroform method (44). RNA was purified using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.) by following the manufacturer's instructions.

Southern and Northern blot analyses.

DNA was digested with the indicated restriction enzymes. Southern and Northern blots were performed as described previously (44). DNA and RNA were transferred to Zeta-Probe nylon membranes (Bio-Rad) and UV cross-linked. High-specific-radioactivity probes were obtained by labeling with [α-32P]dCTP (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences) by PCR as described previously (35). Filters were hybridized with the different probes described below, using a hybridization solution containing 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% bovine serum albumin, 3× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and 1 mM EDTA, and the filters were washed at 63°C in 0.2× SSC and 0.1% SDS.

Gene cloning.

Tcgp63-I and -II were obtained using PCRs on genomic DNA from T. cruzi epimastigotes. The sequences of the primers were as follows: for Tcgp63-I, 5′-ATGCGTCACACTCTGCTAT-3′ (Tcgp63-I.N) and 5′-GTCGTGCGGTCCAAGTCTA-3′ (Tcgp63-I.C); for Tcgp63-II, 5′-ATGCGCCAGCCACGCCGCACCGC-3′ (Tcgp63-II.N) and 5′-TGCCGCCCGCCCCACCATCCACGCTGC-3′ (Tcgp63-II.C). Radioactive probes were obtained by amplification of Tcgp63-I with Tcgp63-I.N/Tcgp63-I.s (5′-CCTCACCCTTTTCACACGAC-3′) and Tcgp63-II with Tcgp63-II.N/Tcgp63-II.s (5′-GGAACCCCACCCTCGTCTC-3′). Sequencing of the products was performed using an ABI 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer). All sequence computational analyses were done using the Lasergene package from DNASTAR, Inc. The alignments were done using the online Workbench server from the University of California at San Diego (http://workbench.sdsc.edu).

Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) treatment.

Cell-derived trypomastigotes (108) were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 500 μl of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies). Parasites were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with or without the addition of 4 U of PI-PLC from Bacillus cereus (Sigma Aldrich) and washed twice in PBS. Harvested pellets and concentrated conditioned media were also prepared for Western blotting (see below).

Parasite extracts.

PBS-washed parasites were resuspended to a concentration of 109 parasites/ml in PBS containing 1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM N-α-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone, 5 mM EDTA, and 10 μM N-(trans-epoxysuccinyl)-l-leucine(4-guanidino)butylamide (E-64). The suspension was kept on ice for 10 min with frequent mixing and centrifuged at 3,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant and the pellet, resuspended in the same buffer solution, were kept and used for the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) experiments. Tcgp63-I was found in the pellet.

Polyacrylamide electrophoresis and Western blots.

Polyacrylamide gels were prepared according to methods previously described (44). Antibodies were obtained by using the synthetic peptide PTcgp63-I (PEGSSITPTGLFTGC), corresponding to amino acid residues 483 to 496 of Tcgp63-I. The C-terminal Cys was added for the covalent linking of the peptide to the carrier Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (Pierce). Western blotting and detection by enhanced chemiluminescence were performed as described previously (44). Wells were loaded using lysates from equivalent numbers of cells. Protease activity gels were done according to methods previously described (29). Briefly, 0.2% gelatin was added to the separating gel, and samples were neither heated nor reduced prior to analysis. After electrophoresis, gels were washed twice in 250 ml of 2.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. After that, the gels were incubated for 3 days at 37°C in a buffer containing 50 mM trisodium citrate, 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM sodium phosphate, and 50 mM sodium borate at pH 8 in the presence of E-64 and, when indicated, 1,10-phenanthroline. Gels were then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Immunofluorescence assays.

A drop of parasites resuspended at 5 × 106/ml in PBS was layered onto 10-mm glass coverslides pretreated with polylysine (Sigma) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Coverslides were saturated in blocking buffer (3% goat serum, 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS) for 1 h, washed twice in PBS, and incubated with anti-Tcgp63-I or preimmune serum diluted in blocking buffer. Coverslides were washed three times and incubated with AlexaFluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. After two washes, coverslides were mounted in antifade reagent (Vector Laboratories), observed under a microscope (Nikon E600) using appropriate fluorescence emission filters, and photographed.

In vitro infectivity studies.

Parasite infection of Vero cells was performed according to methods described previously (20) with some modifications. Vero cells (2 × 104/ml) were cultured for 3 h at 37°C in 24-well plates containing glass coverslips. Trypomastigotes (2 × 106/ml) were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in culture medium (MEM containing 3% [vol/vol] fetal calf serum) in the presence of either PBS, preimmune serum or serum from a T. cruzi-infected rabbit, anti-Tcgp63-I serum, or affinity-purified antibodies against recombinant Tcgp63-I obtained as described previously (25). Parasites from the different treatments were used to infect the Vero cells, with a trypomastigote-to-cell ratio of 100/1. After overnight incubation at 37°C, the medium containing the noninternalized parasites was removed, and the cells were washed three times with PBS and maintained for an additional 72-h period in culture medium. Cells were then stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa, and the percentage of infected cells was estimated by observing at least 500 Vero cells in a Zeiss photomicroscope. The data were analyzed by the Student t test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences reported in this paper have been submitted to GenBank with accession numbers AY266316, AY266317, and AY266318.

RESULTS

Analysis of the gp63 family in Trypanosoma cruzi revealed the presence of two different groups.

In order to analyze the complexity of the gp63 family in T. cruzi, we performed searches for sequences having significant homology to leishmanial gp63 genes. We screened different databases available in our lab, containing genome sequence surveys and expressed sequence tags, from T. cruzi clone CL Brener. This analysis revealed the presence of several related sequences with homology to gp63 genes. With this information, we designed primers (see Materials and Methods) to perform PCRs. By using a first set of primers, two different clones were identified. We named these Tcgp63-Ia and -Ib for T. cruzi gp63 group I member a and b, respectively. The gene obtained with a second set of primers belonged to another gp63 group and was named Tcgp63-II.

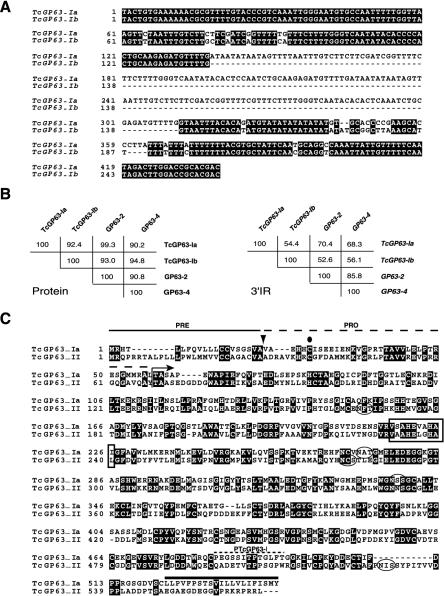

Tcgp63-Ia and -Ib encode proteins of 543 amino acid residues. Sequencing revealed that both genes are highly conserved in their coding regions (97% identical). However, Tcgp63-Ib has a deletion of 175 bp with respect to -Ia in the 3′ intergenic region (3′IR) encoding part of the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) (Fig. 1A). The Tcgp63-I group presents a high degree of homology with the sequences named gp63-1 to -4 previously identified by Grandgenett et al. (22). Tcgp63-Ia protein is 92.4% similar to Tcgp63-Ib and 99.3% to gp63-2. Tcgp63I-b showed the highest homology with gp63-4 (94.8%) (Fig. 1B, left panel). It is interesting that although the coding regions are relatively conserved, the 3′IRs that encode 3′UTRs are highly divergent (Fig. 1B, right panel).

FIG. 1.

Analysis of gp63 members from T. cruzi. (A) Comparison of 3′IRs encoding part of the 3′UTRs from Tcgp63-Ia and -Ib. Black boxes represent identical nucleotides. Dashes indicate gaps for best matching. (B) Percentage of similarity between Tcgp63-Ia, -Ib, gp63-2 (GenBank: AF267162), and gp63-4 (GenBank: AF267505) at the amino acid level (left) or at nucleotide level in the 3′IRs encoding 3′UTRs (right). (C) Comparison of the amino acid sequences of Tcgp63-Ia and -II. Black boxes represent positions of identity. The protease zinc-binding site associated with metalloprotease actiivty is in an open box. Potential N-glycosylation sites are encircled by ovals. The arrowhead and the arrow indicate the end of the proposed pre- and the proregion, respectively. The dot denotes the Cys residue involved in inhibition of protease activity. The hydrophobic C-terminal region of Tcgp63-I is overlined. Dashes show the peptide used to raise specific anti-Tcgp63-I antibodies (PTcgp63-I).

Tcgp63-II encodes a protein composed of 566 amino acid residues that is 42% identical to Tcgp63-I. A comparison of Tcgp63-Ia and -II is shown in Fig. 1C. Both proteins diverged throughout the entire sequence, but the most important differences were (i) that there are two potential N-glycosylation sites in Tcgp63-I, whereas in Tcgp63-II there are three sites, located in different positions, and (ii) in the sequence of the C-terminal region (Fig. 1C). The deduced C-terminal region of Tcgp63-I presents a hydrophobic region of 17 to 20 amino acids (overlined in Fig. 1C) that is compatible with a GPI anchor addition site (36). Conversely, the C-terminal region of Tcgp63-II does not have a hydrophobic sequence at the end. This portion is replaced by a charged region containing three Asp and four Arg residues.

In Leishmania spp., gp63 protein is synthesized as a precursor protein containing a leader peptide (preregion) followed by the proregion. Both are removed from the N-terminal region prior to the localization of gp63 on the cell surface (8). Both Tcgp63 groups have a predicted cleavable signal peptide of 20 and 28 amino acids, respectively (38), which might be cleaved at the sequence SVA/VA or CVA/AD in Tcgp63-Ia and -II, respectively (Fig. 1C, arrowhead). The proregion, by comparison with Leishmania gp63s, is 37 and 40 amino acids long for Tcgp63-Ia and -II, respectively (Fig. 1C, arrow). Both Tcgp63s also have the consensus sequence for the zinc-binding site associated with the metalloprotease activity (box in Fig. 1C). The most important residues for the catalytic activity, both His and Glu in the HEXXH motif (30), are totally conserved. A Cys residue, which might be involved in the inhibition of protease activity by chelation of the active site Zn2+ atom (30), is present in the proregion of both isoforms (Fig. 1C, dot).

Figure 2 shows the alignment of Tcgp63s with the African trypanosome (15), Leishmania guyanensis (49), and C. fasciculata (26) gp63s. Tcgp63-I is 30 to 38% identical to these enzymes. This identity is 26 to 31% for Tcgp63-II. Like gp63s from other organisms, Tcgp63s conserved the position of 18 Cys residues in the mature protein and 1 in the proregion (Fig. 2, asterisks) and almost all Pro residues (Fig. 2, dots), suggesting a high degree of secondary and tertiary structure conservation. In addition, there is also a strong conservation in the catalytic site for metalloprotease activity (Fig. 2, box). However, the N- and C-terminal regions are less conserved.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of gp63 from T. cruzi group I (Tcgp63-Ia), T. cruzi group II (Tcgp63-II), T. brucei gene 1 (Tbgp63-1) (15), L. guyanensis (Lggp63) (49), and C. fasciculata (Cfgp63) (26). Black and gray boxes represent identical positions in all or some gp63 proteins, respectively. Gaps to allow best matches are indicated by dashes. The open box encompass the consensus zinc-binding site associated with metalloprotease activity. The position of 19 Cys and 10 Pro residues conserved in all gp63s are indicated by asterisks and black circles, respectively.

Genomic organization of gp63 in T. cruzi.

To confirm that T. cruzi gp63 belongs to a gene family, we performed Southern blot analysis using probes that correspond to the coding regions of Tcgp63-I and -II (Fig. 3). In both cases, even under stringent washing conditions, the pattern obtained was complex and indicated that the genome of T. cruzi contains multiple genes for each group (Fig. 3A). The digestion of genomic DNA with either EcoRI or BamHI, which do not cut into Tcgp63-II genes, and NotI, which cuts once at the end of the coding region, generated a predominant genomic fragment of about 3.2 kbp (Fig. 3A, large arrowhead). Thus, this fragment might correspond to the minimal fragment size of a repeat unit in a tandem array.

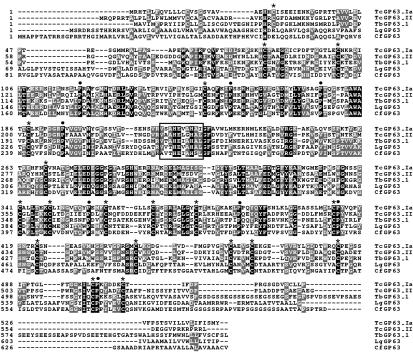

FIG. 3.

Southern blot analysis of Tcgp63 groups. (A) Genomic DNA from T. cruzi CL Brener (4 μg) was digested with the indicated enzymes and hybridized to a probe corresponding to Tcgp63-Ia and -II, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods. The large arrowhead in Tcgp63-II panel indicates the repetitive 3.2-kb fragment (see text). (B) Genomic DNA from T. cruzi Tulahuen2 and CA-I/72 (6 μg) was digested with BamHI and hybridized with the same probes as described for panel A. Markers are in kilobase pairs. Asterisks and arrowheads denote bands shared between T. cruzi CL and Tulahuen2 for Tcgp63-I and -II, respectively (see text).

Several data indicated that Tcgp63-II is more represented in the genome than Tcgp63-I. First, in the Southern blot shown in Fig. 3, the number of bands observed was higher for Tcgp63-II than for Tcgp63-I. Second, a search in a T. cruzi genome sequence survey database (1), using the coding region of Tcgp63-I or -II as query, rendered 3 and 34 hits for Tcgp63-I and -II, respectively. Third, if we use a formula previously described (1) to estimate the copy number of genes from each group, we obtain a value of 5 copies for Tcgp63-I and 62 copies for Tcgp63-II. Moreover, a hybridization of a T. cruzi CL Brener cosmid library ordered in a high-density array (24) produced five positive signals for the Tcgp63-I probe when normalized per haploid genome. Clearly, this number is in agreement with the results from the BLAST search and gene copy number estimations.

In order to study the genomic organization of gp63 groups in different strains of T. cruzi, we performed Southern blots of DNA from Tulahuen2 and CA-I/72 digested with BamHI and hybridized with the same probes described in the legend of Fig. 3A. Like in T. cruzi CL Brener, Tcgp63-I and -II groups have also multiple members in the Tulahuen2 strain and the CA-I/72 clone (Fig. 3B). The organization of the genes from the Tulahuen2 strain is more similar to CL Brener than that from CA-I/72 (Fig. 3, asterisk and arrowheads).

Northern blot analysis of gp63 in T. cruzi.

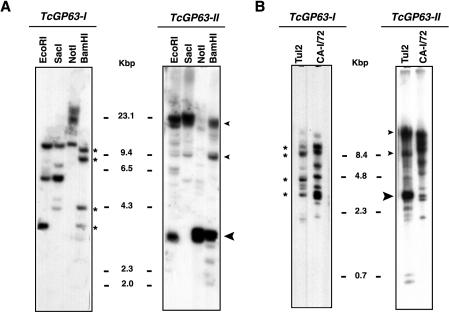

Total RNA was extracted from epimastigotes, amastigotes, and cell-derived trypomastigotes, and Northern blots of these RNAs were hybridized with the same probes used in Southern blot analysis. For Tcgp63-I (Fig. 4A), a different expression pattern was observed depending on the life cycle stage. In epimastigotes, a transcript of 2.1 kb was predominantly detected. Conversely, amastigotes predominantly expressed a 2.4-kb RNA. Trypomastigotes showed both forms but expressed at very low levels. In contrast, Tcgp63-II RNAs were detected as two transcripts of 2.6 and 2.8 kb, which presented low steady-state levels in all stages analyzed. However, in amastigote forms the expression was slightly higher (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis of T. cruzi gp63. Total RNA (15 μg/lane) was fractionated in a 1.5% formaldehyde-containing agarose gel and transferred to nylon membrane. (A and B) RNA was extracted from T. cruzi CL Brener epimastigotes (E), amastigotes (A), and cell-derived trypomastigotes (T). The probes used were the same as those described in the legend of Fig. 3. To control for equal loading of RNA in each lane, the membranes were stripped and rehybridized with a T. cruzi 24S ribosomal probe (lower panel). (C and D) RNA was extracted from T. cruzi epimastigotes SylvioX10, CA-I/72, Tulahuen2 and Y and hybridized with the same probes as those described for panels A and B.

In order to compare the expression pattern of Tcgp63 RNAs among different strains of T. cruzi, we performed Northern blots using RNA from epimastigote forms of the clones SylvioX10 and CA-I/72 as well as the strains Tulahuen2 and Y. In all strains studied, the RNAs detected were the same as that in CL Brener. For Tcgp63-I (Fig. 4C), all the strains except SylvioX10 predominantly showed the 2.1-kb band. SylvioX10, in contrast, overexpressed the 2.4-kb band normally observed in CL Brener amastigotes. In strain Y, the expression was lower than in the other strains, and the 2.4-kb transcript seemed to be absent. In the case of Tcgp63-II, as in CL Brener, there was negligible RNA expression in all the strains analyzed (Fig. 4D).

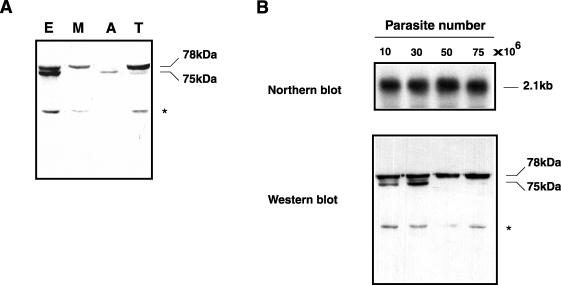

Tcgp63-I proteins are expressed in all life cycle stages of T. cruzi.

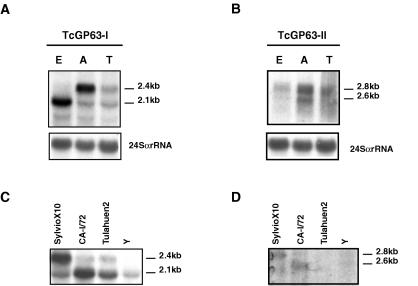

To further analyze the expression of Tcgp63-I group members (the ones with a predicted GPI anchor), we prepared a polyclonal antiserum. For this purpose we designed a Tcgp63-I sequence-derived peptide, PTcgp63-I (see Fig. 1C). Cell lysates, prepared with the same quantities of parasites from the different stages, were fractionated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, and proteins were detected by Western blot analysis. As shown here, Tcgp63-I was found in the resuspended pellets obtained from all developmental stages of T. cruzi life cycle (Fig. 5A), indicating its possible association with membranes. Two major protein bands, with apparent molecular masses of 75 and 78 kDa, were detected in the epimastigote stage with anti-Tcgp63-I serum. Only the upper band was detected in metacyclic trypomastigotes, whereas only the lower band was apparent in amastigotes. Cell-culture trypomastigotes presented both protein bands, but the 78-kDa component was predominant (Fig. 5A). A minor band of approximately 45 kDa was sometimes detected with anti-Tcgp63-I serum (Fig. 5, asterisk). This band disappeared after competition with PTcgp63-I (data not shown). This result indicates that this band is specific and may belong to a differentially processed form of Tcgp63-I or to another group member with lower molecular weight.

FIG. 5.

gp63-I expression in T. cruzi developmental stages. (A) Parasites were lysed by addition of 1% NP-40 to epimastigotes (E), metacyclic trypomastigotes (M), amastigotes (A) and cell-derived trypomastigotes (T). Pellet fractions from 30 × 106 parasites were separated by a 10% SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with a 1/500 dilution of polyclonal anti-Tcgp63-I serum. (B) Cultured epimastigotes (100 × 106) were harvested on sequential days during in vitro development from log to stationary phase. At each point, half of the parasites were extracted with TRIzol reagent, and 15 μg of total RNA was separated on formaldehyde-containing agarose gel, transferred and probed with 32P-labeled Tcgp63-I (upper part). The other half was extracted, and 30 × 106 parasites were loaded and prepared for Western blot (lower part). The gel labels 10, 30, 50, and 75 (all × 106) indicate the density of the culture at each point analyzed in parasites per milliliter. The asterisks indicate a minor band of ∼45 kDa sometimes detected with anti-Tcgp63-I serum.

Previous reports documented in Leishmania chagasi an increase in the amount of gp63 protein during culture growth of promastigotes from logarithmic to stationary phase (40). They also demonstrated that this increase in quantity is associated with the expression of RNA transcripts derived from different gp63 genes. To test if a similar effect might be observed with Tcgp63-I in T. cruzi, epimastigotes were harvested on sequential days from logarithmic to stationary phase of growth, and the amount of RNA and protein was determined by Northern and Western blots, respectively. In Fig. 5B, we present a Northern blot probed with Tcgp63-I (upper panel). Parallel immunoblots of the same samples were developed with anti-Tcgp63-I serum (Fig. 5B, lower panel). During the entire growth curve, epimastigotes expressed the same 2.1-kb transcript detected in Fig. 4A. However, the protein profile changed upon parasite growth. In early-logarithmic phase, T. cruzi expressed the two forms of the protein of 75 and 78 kDa, but in late-logarithmic phase, the lower-size form disappeared and only the 78-kDa protein band was detected. This protein form is the same one that is present in metacyclic trypomastigote extracts. It might, therefore, be related to an intermediate differentiating stage of the parasite (see Discussion).

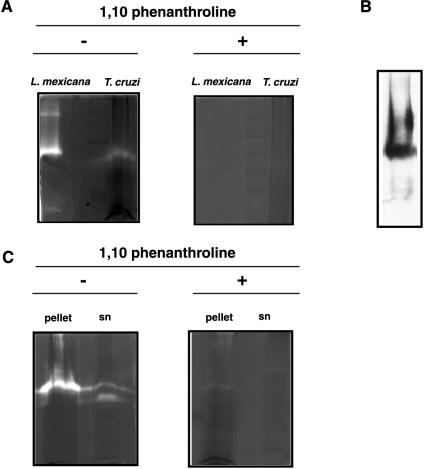

Tcgp63-I is an active metalloprotease.

In order to analyze the metalloprotease activity of Tcgp63, we performed assays with gelatin-containing gels with extracts from epimastigotes of T. cruzi and used promastigotes of L. mexicana mexicana as a control. The quantity of parasites needed to detect protease activity was 50 times higher in epimastigotes than with Leishmania promastigotes (250 × 106 versus 5 × 106 parasites, respectively) (Fig. 6A). This result is consistent with the relative abundance of the protein in each parasite species. It is known that in Leishmania gp63 represents approximately 1% of the total cell protein (19).

FIG. 6.

Metalloprotease activity of T. cruzi gp63-I. (A) L. mexicana mexicana promastigotes (5 × 106) and epimastigotes of T. cruzi CL Brener (250 × 106) were extracted as described in Materials and Methods. The NP-40-insoluble fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (7.5%) on a 0.2% gelatin-containing gel, without heating or reduction prior to electrophoresis. Gels were incubated at 37°C for 72 h in reaction buffer (see Materials and Methods). Proteolytic activity was detected as a clear band on a Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gelatin background (left panel), which disappeared after incubation with the specific inhibitor 1,10 phenanthroline (right panel). (B) The T. cruzi sample (70 × 106 epimastigotes) was run in a gel as described for panel A but without gelatin, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Tcgp63-I serum. (C) The NP-40-insoluble fraction from 300 × 106 T. cruzi epimastigotes was treated with PI-PLC for 1 h at 37°C. After centrifugation, the insoluble (pellet) and soluble (sn) fractions were analyzed as described for panel A.

The protease activity detected in the epimastigote and promastigote forms of T. cruzi and L. mexicana mexicana, respectively, was inhibited by 1,10-phenanthroline (Fig. 6A), indicating that this activity corresponded to a metalloprotease. The activity was highest at pH 8, although there was also gelatinolytic activity at pH values ranging from 6 to 10 (data not shown), as was previously described for Leishmania (17). In amastigote and trypomastigote extracts, we were unable to detect protease activity, even when 300 × 106 parasites were used per lane. We cannot rule out the possibility that a metalloprotease activity is present in these stages, but if present, it is so low that it was not detected in our gelatin-containing gels, at least in the conditions assayed.

To further analyze the identity of this metalloprotease activity, a polyacrylamide gel was prepared in the same conditions as those for the procedures whose results are shown in Fig. 6A, except that the gelatin in the gel was omitted and only 70 × 106 parasites were used to avoid protein overloading. After that, a Western blot was probed with a serum against Tcgp63-I. A band with an electrophoretic mobility similar to that of the metalloprotease activity was detected, suggesting that the activity corresponds at least in part to Tcgp63-I (Fig. 6B). If we compare the amount of protein detected by Western blots with the gelatinolytic activity, we could infer that in T. cruzi the metalloprotease activity is very low, at least in the conditions tested so far.

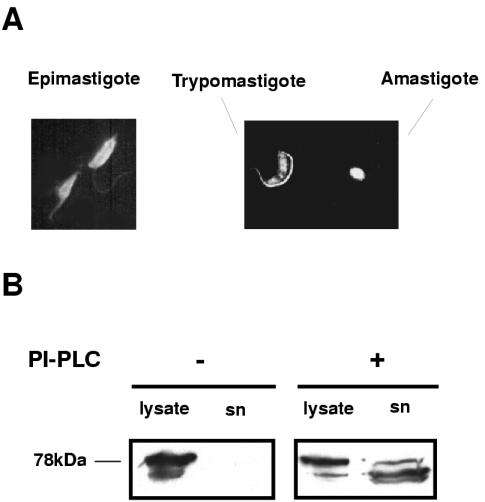

Tcgp63-I members are surface proteins bound to the membrane by a GPI anchor moiety.

The surface localization of Tcgp63-I was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence on nonpermeabilized parasites. The entire surface of epimastigotes and amastigotes was clearly labeled by anti-Tcgp63-I serum. On the other hand, cell-derived trypomastigotes were mainly labeled in the region of the flagellum (Fig. 7A), although some label was seen in the rest of the parasite. When using preimmune serum, we did not detect signal in any of the parasite stages evaluated (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

gp63 is expressed at the cell surface of T. cruzi. (A) Epimastigotes and a mixture of cell-derived trypomastigotes and amastigotes were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. Parasites were probed by using anti-Tcgp63-I serum raised in rabbit and photographed (magnification, ×180) under fluorescence. (B) Intact live cell-derived trypomastigotes were treated (+) or not (−) with B. cereus PI-PLC for 1 h at 37°C. Normal morphology and motility was controlled by microscopic observation before and after incubation. Parasites were centrifuged, and aliquots from parasite extracts (lysate) and culture medium supernatants (sn) were probed with anti-Tcgp63-I serum.

As Tcgp63-I proteins have a putative GPI anchor signal, as deduced by sequence analysis (Fig. 1C), the possible presence of such modification was evaluated by PI-PLC treatment on intact cell-derived trypomastigotes. The addition of PI-PLC to living trypomastigotes caused the decrease of the signal in lysates from treated parasites when probed with an anti-Tcgp63-I serum in Western blotting. This signal was detected in the culture supernatant only after PI-PLC treatment (Fig. 7B). As expected, the molecular weight of the GPI free form generated after the enzymatic treatment was slightly lower than the native one.

The metalloprotease activity in the pellet fraction shown in Fig. 6A could be partially released by PI-PLC treatment (Fig. 6C). A band of the expected size for Tcgp63-I and with protease activity was clearly seen in the soluble fraction (Fig. 6C, left panel). This activity was inhibited by 1,10 phenanthroline (Fig. 6C, right panel).

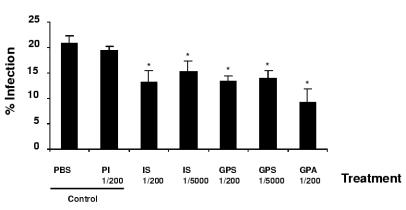

T. cruzi gp63-I group is implicated in the infection of mammalian cells in vitro.

As gp63 in T. cruzi was expressed in the infective stages (metacyclic and cell-derived trypomastigotes), we investigated whether its presence could be implicated in infection. To study this possibility, we performed in vitro neutralization assays by using trypomastigote forms preincubated under different conditions to infect Vero cells (Fig. 8). Trypomastigote viability was not affected when preincubated with different sera (data not shown). The percentages of infected cells in the control treatments (PBS and preimmune serum) ranged from 19 to 21%. When trypomastigotes were preincubated with serum from infected rabbits or with anti-Tcgp63-I serum, this percentage dropped to 13 to 15%. The effect was more pronounced, i.e., about 50% inhibition, when Tcgp63-I affinity-purified antibodies were used (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

In vitro Vero cell infection assay. Vero cells (2 × 104) were cultured at 37°C in 24-well plates. One hour before infection, trypomastigotes were incubated with PBS, preimmune serum (PI), serum from an infected rabbit (IS), anti-Tcgp63-I serum (GPS), or anti-Tcgp63-I specific antibodies (GPA) at the dilutions indicated. After overnight infection, cells were washed and incubated for 72 h at 37°C. The percentage of infected cells was estimated by observing 500 cells under the microscope. The results are expressed as the percentage of infection (number of infected cells/number of total cells). Values represent the means ± standard deviations of triplicate determinations. Statistically significant differences compared to the control are indicated with asterisks (P < 0.001 by the Student t test).

DISCUSSION

gp63 is a complex, well-studied gene family in Leishmania spp. (9, 16, 50, 51). Our results show for the first time, in a trypanosomatid different from Leishmania, that gp63 is a proteolytically active enzyme bound to the membrane by a GPI anchor and with a possible role in the infection to host cells (see below).

The number of gp63 genes in Leishmania spp. is variable, ranging from 7 to 18, and all with highly conserved coding regions (9, 33, 41, 49, 52, 53). In contrast, T. cruzi has at least 70 genes that code for gp63 homologues (1). Results shown in this paper and others recently obtained in our lab (I. C. Cuevas et al., unpublished data) confirm that there are several groups of genes that belong to the gp63 family, with multiple members in each. In the present work, we have characterized two of these groups, named Tcgp63-I and -II (Fig. 1C). Tcgp63-I genes are similar to those previously described (22). Tcgp63-II, on the other hand, represents a new group not described before, composed mainly by tandemly linked genes (Fig. 3A). Thus, the complexity of gp63 gene family in T. cruzi resembles that observed in L. guyanensis (49), and it is important to mention that the genes described here show the highest homology, among Leishmania species, to gp63s from L. guyanensis.

Tcgp63-I and -II show several characteristic features of gp63s metalloproteases, including putative pre- and prodomains, the consensus site for catalytic activity (HEXXH), several Cys and Pro residues located in positions which are totally conserved, potential N-glycosylation sites, and, in the case of Tcgp63-I, a GPI anchor addition site (Fig. 1C). The amino acid identity between Tcgp63-I and -II is about 42%, and the differences between them are scattered along the sequence. On the other hand, gp63s members of the same strain in Leishmania are in general conserved, and when different, there are clusters of differing amino acid residues (41).

Tcgp63-I was detected at the mRNA and protein levels in all T. cruzi CL Brener developmental stages. An increase of total mRNA level for the gp63 homologue in the amastigote stage had been described for the Tulahuen strain (22). However, we found no evidence for such an increase in CL Brener clone. This suggests that the expression of these mRNAs is different in different T. cruzi strains and clones, as shown for the epimastigote stage in Fig. 4C. All strains studied showed a predominant 2.1-kb mRNA in the epimastigote stage, except for SylvioX10, which had a major 2.4-kb mRNA band. The most important differences between gp63-2, gp63-4 (22), and Tcgp63-Ia and -Ib genes are in the 3′IR regions encoding 3′UTRs (Fig. 1). These regions might be involved in stage-specific regulation, as it normally occurs for gp63 genes in Leishmania (40, 41, 52). For example, Tcgp63-Ia encodes a GU-rich motif (5′-GUUUCGUUUCUUUUGGG-3′) (not shown) described as a recognition site for mRNA-destabilizing factors in T. cruzi (13).

Western blot analysis indicates that heterogeneous Tcgp63-I proteins are expressed in T. cruzi. The molecular mass of the proteins observed ranged from 75 to 78 kDa. The theoretical molecular mass of the mature enzyme is 54 kDa; thus, Tcgp63 is likely to be posttranslationally modified in vivo. Posttranslational differences might include differential N-glycosylation or the presence of a partially processed prodomain. Posttranslational regulation in Tcgp63-I expression might also exist. For example, in the trypomastigote stage, the protein is expressed in similar quantities to that in the epimastigote stage, even though the mRNA steady-state level is higher in this latter stage. In all the stages analyzed, Tcgp63-I proteins are bound to the membrane (Fig. 7A). It would be interesting to investigate whether they are also secreted to the medium as noted recently for L. mexicana gp63 (14).

This is the first report in which a metalloprotease activity is correlated with gp63 expression in T. cruzi (Fig. 6). The metalloprotease nature of the Tcgp63-I family is suggested by its sensitivity toward the metal-chelating 1,10-phenanthroline, as was described previously for the Leishmania enzyme (4). In marked contrast to Leishmania, the T. cruzi enzyme has a very low activity under the conditions tested. In T. brucei, it was suggested that a metalloprotease surface activity is responsible for the shedding of variant surface glycoprotein during differentiation (2). In fact, one of the T. brucei gp63 families is involved in the release of transgenic variant surface glycoprotein from procyclic cells (28). It would be interesting to test if, in T. cruzi, gp63 is active on some of the abundant surface molecules known to be shed during differentiation and/or infection.

It is well-known that in T. cruzi epimastigote cultures, metacyclogenesis occurs spontaneously during stationary phase (10). We have observed a change in the protein profile for Tcgp63-I proteins: as the culture grows, it expresses predominantly a high-molecular-mass form (78 kDa), the same protein form detected in metacyclic trypomastigotes. Thus, the 78-kDa form might be related with infectivity. In sharp contrast to previous L. donovani chagasi reports (40), there is no switch in the nature of the RNAs expressed during in vitro epimastigote culture growth.

Multiple determinants are clearly involved in intracellular parasitism. Among them, the surface glycoproteins like trans-sialidases/sialidases and mucins have been extensively studied and implicated as virulence factors in T. cruzi (21), as well as gp82, a metacyclic stage-specific surface molecule involved in invasion of epithelial cells (37). According to our results, gp63 might be involved in infection of host cells. In fact, trypomastigotes preincubated with anti-Tcgp63-I serum showed a decrease in infectivity (Fig. 8). The antibodies used in this study were raised against a C-terminal extension (Fig. 1C), a region known to be exposed in Leishmania gp63s. This region might be able to interact with antibodies (39). Antibodies against this C-terminal region have been shown to inhibit parasite internalization in L. guyanensis by approximately 30% (39). It is known that gp63 protease activity is not necessary for L. donovani chagasi promastigotes' interaction with CR3 (54). In contrast, protease activity appears to help Leishmania as a mechanism for anticytolysis inside macrophages (47). Thus, Tcgp63 might be important for the initial infection steps, but as it does not have remarkable protease activity, its involvement in the intracellular survival of the parasite is not likely. As the percentage of infection diminished by only ∼30 to 50%, it is possible that molecules other than gp63 may also contribute in the binding of T. cruzi to mammalian cells, as was suggested for the mucins (21) and gp82 antigens (37). It would be interesting to study the molecule in the host cells that interacts with Tcgp63-I and also whether mice immunized with gp63 are more resistant to T. cruzi infection.

The relative abundance of genes is higher for the Tcgp63-II group (Fig. 3B), the one without a predicted GPI anchor addition site (Fig. 1C) and which had the lowest RNA expression levels under the conditions assayed in all strains (Fig. 4B and D). T. cruzi presents at least two gene families thoroughly described: trans-sialidase and mucin like. These families are composed of about 150 and 700 genes, respectively, and are likely to be the most abundant proteins on the surface of the parasite (21). One intriguing question is why T. cruzi has about 60 Tcgp63-II genes if they are expressed at a very low level, at least as mRNAs. Moreover, we have evidence for the presence of still another group, Tcgp63-III, which may consist essentially of pseudogenes (I. C. Cuevas et al., unpublished data). Further work will be necessary to elucidate the mechanism of individual Tcgp63 members' expression pattern and their role in host cell interactions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the World Bank/UNDP/WHO Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Disease (TDR), the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina), the Carrillo-Oñativia Fellowship, Ministerio de Salud (Argentina), and the Fundación Antorchas (Argentina) to D.O.S. and TDR/WHO Project 970629 and Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica SECyT (Argentina) PICT no. 01-06578 grants to J.J.C. I.C.C. is a Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas (CIC) fellow. D.O.S. and J.J.C. are researchers from the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnicas (CONICET).

We thank Iván D'Orso for careful reading of the manuscript, Berta Franke de Cazzulo and Liliana Sferco for their technical assistance with parasites, Fernan Agüero and Ramiro Verdun for help with figures, and Ulf Hellman and Ulla Engström from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Uppsala Branch, Sweden, for synthesis of the peptides.

Editor: W. A. Petri, Jr.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agüero, F., R. E. Verdún, A. C. C. Frasch, and D. O. Sánchez. 2000. A random sequencing approach for the analysis of the Trypanosoma cruzi genome: general structure, large gene and repetitive DNA families, and gene discovery. Genome Res. 10:1996-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangs, J. D., D. A. Ransom, M. Nimick, G. Christie, and N. M. Hooper. 2001. In vitro cytocidal effects on Trypanosoma brucei and inhibition of Leishmania major gp63 by peptidomimetic metalloprotease inhibitors. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 114:111-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaldo, M. C., L. N. d'Escoffier, J. M. Salles, and S. Goldenberg. 1991. Characterization and expression of proteases during Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. Exp. Parasitol. 73:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier, J., C. Bordier, H. Vogel, R. Reichelt, and R. Etges. 1989. Characterization of the promastigote surface protease of Leishmania as a membrane-bound zinc endopeptidase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 37:235-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouvier, J., R. J. Etges, and C. Bordier. 1985. Identification and purification of membrane and soluble forms of the major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 260:15504-15509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvier, J., P. Schneider, and R. Etges. 1995. Leishmanolysin: surface metalloproteinase of Leishmania. Methods Enzymol. 248:614-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler, M. J. 1998. Leishmanolysin, p. 1135-1140. In A. J. Barret, N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner (ed.), Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 8.Button, L. L., and W. R. McMaster. 1988. Molecular cloning of the major surface antigen of Leishmania. J. Exp. Med. 167:724-729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Button, L. L., D. G. Russell, H. L. Klein, E. Medina-Acosta, R. E. Karess, and W. R. McMaster. 1989. Genes encoding the major surface glycoprotein in Leishmania are tandemly linked at a single chromosomal locus and are constitutively transcribed. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 32:271-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camargo, E. P. 1964. Growth and differentiation in Trypanosoma cruzi. I. Origin of metacyclic trypanosomes in liquid media. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 6:93-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, C. S., and K. P. Chang. 1986. Monoclonal antibody affinity purification of a Leishmania membrane glycoprotein and its inhibition of Leishmania-macrophage binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83:100-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhuri, G., M. Chaudhuri, A. Pan, and K. P. Chang. 1989. Surface acid proteinase (gp63) of Leishmania mexicana. A metalloenzyme capable of protecting liposome-encapsulated proteins from phagolysosomal degradation by macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 264:7483-7489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Orso, I., and A. C. Frasch. 2001. TcUBP-1, a developmentally regulated U-rich RNA-binding protein involved in selective mRNA destabilization in trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:34801-34809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis, M., D. K. Sharma, J. D. Hilley, G. H. Coombs, and J. C. Mottram. 2002. Processing and trafficking of Leishmania mexicana gp63. Analysis using GP18 mutants deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol protein anchoring. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27968-27974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Sayed, N. M., and J. E. Donelson. 1997. African trypanosomes have differentially expressed genes encoding homologues of the Leishmania gp63 surface protease. J. Biol. Chem. 272:26742-26748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espinoza, J. R., A. C. Skinner, C. R. Davies, A. Llanos-Cuentas, J. Arevalo, C. Dye, W. R. McMaster, J. W. Ajioka, and J. M. Blackwell. 1995. Extensive polymorphism at the Gp63 locus in field isolates of Leishmania peruviana. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 72:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etges, R., J. Bouvier, and C. Bordier. 1986. The major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes is a protease. J. Biol. Chem. 261:9098-9101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etges, R., J. Bouvier, and C. Bordier. 1986. The major surface protein of Leishmania promastigotes is anchored in the membrane by a myristic acid-labeled phospholipid. EMBO J. 5:597-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etges, R. J., J. Bouvier, R. Hoffman, and C. Bordier. 1985. Evidence that the major surface proteins of three Leishmania species are structurally related. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 14:141-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franke de Cazzulo, B. M., J. Martínez, M. J. North, G. H. Coombs, and J. J. Cazzulo. 1994. Effects of proteinase inhibitors on the growth and differentiation of Trypanosoma cruzi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 124:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frasch, A. C. C. 2000. Functional diversity in the trans-sialidase and mucin families in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol. Today 16:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandgenett, P. M., B. C. Coughlin, L. V. Kirchhoff, and J. E. Donelson. 2000. Differential expression of gp63 genes in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 110:409-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greig, S., and F. Ashall. 1990. Electrophoretic detection of Trypanosoma cruzi peptidases. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 39:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanke, J., D. O. Sánchez, J. Henrihsson, L. Aslund, U. Pettersson, A. C. Frasch, and J. D. Hoheisel. 1996. Mapping the Trypanosoma cruzi genome: analyses of representative cosmid libraries. BioTechniques 21:686-688, 690-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harlow, E., and D. Lane. 1999. Using antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 26.Inverso, J. A., E. Medina-Acosta, J. O'Connor, D. G. Russell, and G. A. Cross. 1993. Crithidia fasciculata contains a transcribed leishmanial surface proteinase (gp63) gene homologue. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 57:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi, P. B., B. L. Kelly, S. Kamhawi, D. L. Sacks, and W. R. McMaster. 2002. Targeted gene deletion in Leishmania major identifies leishmanolysin (gp63) as a virulence factor. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 120:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaCount, D. J., A. E. Gruszynsky, P. M. Grandgenett, J. D. Bangs, and J. E. Donelson. 2003. Expression and function of TbMSP (gp63) genes in African trypanosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 278:24658-24664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowndes, C. M., M. C. Bonaldo, N. Thomaz, and S. Goldenberg. 1996. Heterogeneity of metalloprotease expression in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology 112:393-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macdonald, M. H., C. J. Morrison, and W. R. McMaster. 1995. Analysis of the active site and activation mechanism of the Leishmania surface metalloproteinase gp63. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1253:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGwire, B., and K. P. Chang. 1994. Genetic rescue of surface metalloproteinase (gp63) deficiency in Leishmania amazonensis variants increases their infection of macrophages at the early phase. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 66:345-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGwire, B. S., and K. P. Chang. 1996. Posttranslational regulation of a Leishmania HEXXH metalloprotease (gp63). The effects of site-specific mutagenesis of catalytic, zinc binding, N-glycosylation, and glycosyl phosphatidylinositol addition sites on N-terminal end cleavage, intracellular stability, and extracellular exit. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7903-7909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medina-Acosta, E., R. E. Karess, and D. G. Russell. 1993. Structurally distinct genes for the surface protease of Leishmania mexicana are developmentally regulated. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 57:31-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medina-Acosta, E., R. E. Karess, H. Schwartz, and D. G. Russell. 1989. The promastigote surface protease (gp63) of Leishmania is expressed but differentially processed and localized in the amastigote stage. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 37:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mertz, L. M., and A. Rashtchian. 1994. Nucleotide imbalance and polymerase chain reaction: effects on DNA amplification and synthesis of high specific activity radiolabeled DNA probes. Anal. Biochem. 221:160-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moran, P., and I. W. Caras. 1994. Requirements for glycosylphosphatidylinositol attachment are similar but not identical in mammalian cells and parasitic protozoa. J. Cell Biol. 125:333-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neira, I., F. A. Silva, M. Cortez, and N. Yoshida. 2003. Involvement of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes surface molecule gp82 in adhesion to gastric mucin and invasion of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 71:557-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. von Heine. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Prot. Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puentes, F., F. Guzman, V. Marin, C. Alonso, M. E. Patarroyo, and A. Moreno. 1999. Leishmania: fine mapping of the Leishmanolysin molecule's conserved core domains involved in binding and internalization. Exp. Parasitol. 93:7-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramamoorthy, R., J. E. Donelson, K. E. Paetz, M. Maybodi, S. C. Roberts, and M. E. Wilson. 1992. Three distinct RNAs for the surface protease gp63 are differentially expressed during development of Leishmania donovani chagasi promastigotes to an infectious form. J. Biol. Chem. 267:1888-1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts, S. C., K. G. Swihart, M. W. Agey, R. Ramamoorthy, M. E. Wilson, and J. E. Donelson. 1993. Sequence diversity and organization of the msp gene family encoding gp63 of Leishmania chagasi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62:157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell, D. G. 1987. The macrophage-attachment glycoprotein gp63 is the predominant C3-acceptor site on Leishmania mexicana promastigotes. Eur. J. Biochem. 164:213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell, D. G., and S. D. Wright. 1988. Complement receptor type 3 (CR3) binds to an Arg-Gly-Asp-containing region of the major surface glycoprotein, gp63, of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Exp. Med. 168:279-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 45.Schneider, P., and T. A. Glaser. 1993. Characterization of a surface metalloprotease from Herpetomonas samuelpessoai and comparison with Leishmania major promastigote surface protease. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 58:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider, P., J. P. Rosat, J. Bouvier, J. Louis, and C. Bordier. 1992. Leishmania major: differential regulation of the surface metalloprotease in amastigote and promastigote stages. Exp. Parasitol. 75:196-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seay, M. B., P. L. Heard, and G. Chaudhuri. 1996. Surface Zn-proteinase as a molecule for defense of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis promastigotes against cytolysis inside macrophage phagolysosomes. Infect. Immun. 64:5129-5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soteriadou, K. P., M. S. Remoundos, M. C. Katsikas, A. K. Tzinia, V. Tsikaris, C. Sakarellos, and S. J. Tzartos. 1992. The Ser-Arg-Tyr-Asp region of the major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania mimics the Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser cell attachment region of fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:13980-13985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steinkraus, H. B., J. M. Greer, D. C. Stephenson, and P. J. Langer. 1993. Sequence heterogeneity and polymorphic gene arrangements of the Leishmania guyanensis gp63 genes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 62:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Victoir, K., A. L. Banuls, J. Arevalo, A. Llanos-Cuentas, R. Hamers, S. Noel, S. De Doncker, D. Le Ray, M. Tibayrenc, and J. C. Dujardin. 1998. The gp63 gene locus, a target for genetic characterization of Leishmania belonging to subgenus Viannia. Parasitology 117:1-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Victoir, K., J. C. Dujardin, S. de Doncker, D. C. Barker, J. Arevalo, R. Hamers, and D. Le Ray. 1995. Plasticity of gp63 gene organization in Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and Leishmania (Viannia) peruviana. Parasitology 111:265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Voth, B. R., B. L. Kelly, P. B. Joshi, A. C. Ivens, and W. R. McMaster. 1998. Differentially expressed Leishmania major gp63 genes encode cell surface leishmanolysin with distinct signals for glycosylphosphatidylinositol attachment. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 93:31-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webb, J. R., L. L. Button, and W. R. McMaster. 1991. Heterogeneity of the genes encoding the major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania donovani. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 48:173-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson, M. E., and K. K. Hardin. 1990. The major Leishmania donovani chagasi surface glycoprotein in tunicamycin-resistant promastigotes. J. Immunol. 144:4825-4834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Health Organization. 1997. Tropical disease research, progress 1995-1996. WHO Publications, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 56.Zingales, B., M. E. Pereira, R. P. Oliveira, K. A. Almeida, E. S. Umezawa, R. P. Souto, N. Vargas, M. I. Cano, J. F. da Silveira, N. S. Nehme, C. M. Morel, Z. Brener, and A. Macedo. 1997. Trypanosoma cruzi genome project: biological characteristics and molecular typing of clone CL Brener. Acta Trop. 68:159-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]