Abstract

Group A streptococci (GAS) can use heme and hemoproteins as sources of iron. However, the machinery for heme acquisition in GAS has not been firmly revealed. Recently, we identified a novel heme-associated cell surface protein (Shp) made by GAS. The shp gene is cotranscribed with eight downstream genes, including spy1795, spy1794, and spy1793 encoding a putative ABC transporter (designated HtsABC). In this study, spy1795 (designated htsA) was cloned from a serotype M1 strain, and recombinant HtsA was overexpressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity. HtsA binds 1 heme molecule per molecule of protein. HtsA was produced in vitro and localized to the bacterial cell surface. GAS up-regulated transcription of htsA in human blood compared with that in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract. The level of the htsA transcript dramatically increased under metal cation-restricted conditions compared with that under metal cation-replete conditions. The cation content, cell surface location, and gene transcription of HtsA were also compared with those of MtsA and Spy0385, the lipoprotein components of two other putative iron acquisition ABC transporters of GAS. Our results suggest that HtsABC is an ABC transporter that may participate in heme acquisition in GAS.

Iron is essential for the multiplication and survival of most bacterial pathogens in host environments (32). Most iron in humans and animals is located intracellularly in complexes with proteins such as hemoglobin, myoglobin, other heme-containing proteins, ferritin, and non-heme iron-containing proteins. Small amounts of iron are present extracellularly as complexes with transferrin in serum and lymph and with lactoferrin in mucosal secretions or released from phagocytic cells. Ferric iron has extremely low solubility in water at physiological pH, and there is little free iron to support bacterial growth in mammalian hosts (33). Therefore, hemoproteins and non-heme iron-protein complexes are the iron sources for pathogenic bacteria in vivo (25).

Gram-negative bacterial pathogens assimilate iron or heme from host iron- or heme-protein complexes by using systems based on siderophores, hemophores, or specific receptors (13-15, 26). Siderophores (low-molecular-weight iron chelators) and hemophores (heme-binding proteins) are secreted by pathogens to sequester iron and heme from host proteins, respectively. Siderophore-iron or hemophore-heme complexes are taken up by an outer membrane receptor and transported across the outer and cytoplasmic membranes by a TonB-dependent process (20) and an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter in gram-negative pathogens (16), respectively. Alternatively, iron or heme can be directly sequestered from host proteins by specific receptors on the surfaces of bacteria and brought across the cytoplasmic membrane by ABC transporters (15). Recent studies suggest that cell surface proteins and ABC transporters are involved in heme acquisition by gram-positive bacteria (23).

Streptococcus pyogenes, commonly referred to as group A streptococcus (GAS), is a gram-positive bacterial pathogen causing a variety of human diseases including pharyngitis, scarlet fever, necrotizing fasciitis, streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, and postinfection sequelae such as acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease, and glomerulonephritis (7). GAS can take up heme from hemoglobin and haptoglobin-hemoglobin complexes (11). Exogenously supplied heme or host heme proteins (hemoglobin, myoglobin, and catalase), but not iron-loaded transferrin and lactoferrin, support in vitro growth of GAS under iron-restricted conditions (9). However, little is known about the machinery for heme acquisition in GAS. Recently, a novel heme-associated cell surface protein (Shp) made by GAS was identified (21). The shp gene is cotranscribed with eight contiguous downstream genes (21), including spy1795 (designated htsA), spy1794 (htsB), and spy1793 (htsC), encoding a putative ABC transporter (designated heme transporter of S. pyogenes, or HtsABC). We report here the preparation, heme binding, and cell surface location of HtsA and its comparison in cation content, cell surface location, and gene transcription with MtsA and Spy0385, the lipoprotein components of two other putative iron acquisition ABC transporters of GAS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The pET-His2 vector was obtained by inserting the XbaI/EcoRI fragment of pET-His (6) into pET-21b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) linearized by XbaI and EcoRI. Hemin, imidazole, and Sephadex G-25 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies specific for HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385 were prepared by Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, Tex.) by using recombinant proteins as antigens and immunoabsorbents. As determined by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, the affinity-purified antibodies specific for MtsA, HtsA, and Spy0385 had titers of 1/209,000, 1/281,380, and 1/142,290, respectively. The control rabbit antibody was raised against recombinant phospholipase A2 (Sla) encoded by sla in strain MGAS315 (serotype M3) (2). Strain MGAS5005 lacks the sla gene. The rabbit anti-Sla antibody was purified by analogous procedures and purchased from Bethyl Laboratories.

Bacterial strains and growth.

GAS strain MGAS5005 (serotype M1) has been described previously and characterized extensively (17). GAS was grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.2% yeast extract (THY). Iron-restricted conditions were achieved by treating THY with the chelating resin Chelex 100 (Sigma) and supplementing it with 60 μM MgCl2 (DTHYMg) or 0.4 mM (each) CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, and ZnCl2 (DTHYM). Tryptose agar with 5% sheep blood (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) or brain heart infusion agar (Difco Laboratories) was used as the solid medium. Escherichia coli strains NovaBlue and BL21(DE3) (Novagen) were used for gene cloning and protein expression, respectively.

Gene cloning.

The htsA (spy1795), mtsA (spy0453), and spy0385 genes were cloned from MGAS5005 by using vectors and primers summarized in Table 1. MtsA was expressed as a mature form without any tag in which the first amino acid residue of the mature protein, cysteine, was replaced by a glycine residue. HtsA and Spy0385 each had 11 amino acid residues (MHHHHHHLETMG) fused to the second amino acid residue of each mature protein. Therefore, all three proteins were expressed as unlipidated cytosolic proteins without secretion signal sequences. The cloned genes were sequenced to rule out spurious mutations.

TABLE 1.

Primers, vectors, cloning sites, and recombinant plasmids in gene cloning

| ORF | Primers | Vector/cloning sites | Plasmid | His tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| spy0385 | 5′-ACCATGGGTGGTAATCAAGCAACTAATC-3′ | pET-His2/NcoI, EcoRI | pLP385 | + |

| 5′-CGAATTCTTAGTTTTCACTTGATAAGATTG-3′ | ||||

| mtsA | 5′-ACCATGGGTTCGTCAACTGGCACTAAAAC-3′ | pET21d/NcoI, EcoRI | pLP453 | − |

| 5′-CGAATTCTTATTTTGCTAGACCTTCAG-3′ | ||||

| htsA | 5′-ACCATGGGTGGTAATCAAGCAACTAATC-3′ | pET-His2/NcoI, EcoRI | pLP1795 | + |

| 5′-CGAATTCTTAGTTTTCACTTGATAAGATTG-3′ |

Expression of recombinant proteins.

For expression of MtsA, E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing mtsA were grown overnight at 37°C in 6 liters of Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with 100 mg of ampicillin/liter (LBA). For expression of HtsA and Spy0385, the gene-containing E. coli BL21(DE3) bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of approximately 1.0 in 4 liters of LBA at 37°C, and expression was induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 6 h. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation to yield a cell paste used for protein purification.

Protein purification.

All solutions were buffered with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) (THCl). The cell paste described above was suspended in 70 ml of THCl and sonicated on ice for 15 min. The samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min to remove cell debris, and the lysate containing recombinant protein was collected. Dialysis was done against 3 liters of THCl at 4°C for 30 h with two buffer changes. Purified proteins were concentrated by (NH4)2SO4 precipitation at 70% of saturation, dialyzed against THCl, and stored at −20°C. All centrifugation was carried out at 20,000 × g for 15 min.

(i) Purification of MtsA.

The cell lysate was loaded onto a 2.5- by 10-cm DEAE Sepharose column, and the column was washed with 50 ml of THCl. (NH4)2SO4 (21 g) was added to 100 ml of the flowthrough pool. The sample was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was loaded onto a 2.5- by 5-cm phenyl Sepharose column. The column was washed with 170 ml of 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and the protein was eluted with a 100-ml linear gradient of 1.5 to 1.0 M (NH4)2SO4. Fractions containing recombinant MtsA were pooled.

(ii) Purification of Spy0385.

NaCl (4 g) was added to 70 ml of cell lysate. The sample was loaded onto a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column (1 by 5 cm), the column was washed with 100 ml of 1 M NaCl in THCl, and the protein was eluted with a 50-ml gradient of 0 to 0.15 M imidizole in the 1 M NaCl solution. The protein obtained was dialyzed, loaded onto a 1.5- by 10-cm Q-Sepharose column, and eluted with THCl.

(iii)Purification of HtsA.

Initial chromatography of HtsA using a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column was carried out exactly as described above. The eluted protein was dialyzed, loaded onto a 1.5- by 10-cm Q-Sepharose column, and eluted with a 100-ml linear gradient of 0 to 0.2 M NaCl in THCl and then with 50 ml of 0.2 M NaCl in THCl.

Reconstitution of holo-HtsA.

Holo-HtsA was reconstituted from heme and apo-HtsA present in the purified HtsA sample. HtsA (0.3 ml at 0.57 mM) was incubated with 0.6 mM heme in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) for 10 min, loaded onto a Sephadex G-25 column (0.5 by 30 cm), and eluted with THCl. HtsA without free heme was collected.

Determination of protein concentration and heme content.

Protein concentrations were determined with the modified Lowry protein assay kit purchased from Pierce (Rockford, Ill.) with bovine serum albumin as a standard (22). A pyridine hemochrome assay (12) was used to assess the existence and content of heme associated with HtsA. Purified or reconstituted HtsA in 750 ml of THCl was mixed with 175 ml of pyridine, 75 μl of 1 N NaOH, and about 2 mg of sodium hydrosulfite, and the optical spectrum was recorded immediately with an Ultraspec 4000 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Pharmacia). Heme content was determined by measuring the absorbance at 418 nm (ɛ418, 191.5 mM−1 cm−1) (12).

Measurement of iron, manganese, and zinc by ICP-MS.

Levels of iron, manganese, and zinc in HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385 were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) conducted by procedures described previously (21) using an HP4500 ICP-MS instrument equipped with an CETAC ASX-500 autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, Calif.). Multielement calibration standard-2A (Agilent Technologies), a certified standard, was used to generate calibration curves.

Analysis of gene transcription.

Gene transcripts present in GAS grown in THY, DTHYM, DTHYMg, or heparinized human blood were assessed by real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (TaqMan) analysis. GAS grown in THY, DTHYM, or DTHYMg were harvested at an OD600 of 0.2. Culture of GAS in human blood was carried out by inoculating 108 CFU of GAS per ml of fresh nonimmune blood and rotating tubes end to end at 37°C for 4 h. The GAS culture in blood was incubated with 3 volumes of RNAprotect Bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) for 5 min at room temperature, and GAS bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 2 min. The harvested bacteria were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C prior to RNA isolation. Total RNA was isolated as described previously (21). High RNA quality was confirmed spectrophotometrically with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and an RNA 6000 LabChip kit (Agilent Technologies).

TaqMan analysis was performed as previously described (5) with probes and primers specific for gyrA, htsA, mtsA, or spy0385 (listed in Table 2). Oligonucleotide probes were labeled at the 5′ end with the reporter dye 5-carboxyfluorescein and at the 3′ end with the quencher N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine. The RT-PCR mixture (25 μl) contained the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix reagents (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems), 500 nM each gene-specific primer, 100 nM each probe, and 30 ng of total RNA template or known quantities of MGAS5005 genomic DNA as the standard. Triplicates of samples, standard, and controls were set up in a single 96-well plate for all four genes tested. Amplification and detection of specific products were performed with the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) with a cycle profile of 1 cycle at 48°C for 30 min, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The critical threshold cycle (Ct) is defined as the cycle at which the fluorescence becomes detectable above background and is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the initial number of template molecules. A standard curve was plotted for each primer-probe set, with Ct values obtained from amplification of known quantities of MGAS5005 genomic DNA. The standard curves were used to transform Ct values to the relative number of DNA molecules. Control reactions that did not contain reverse transcriptase revealed no contamination of genomic DNA in any RNA sample.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers and fluorescent probes used to quantitate cDNA

| Gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Probea (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| htsA | CAGCACCCTAAAACGGCTAAA | GGTCACAGATATCAACCACAGCAA | AGACTGAACAGCAGAGAATTGTAGCCACTTCG |

| mtsA | GTCGTGGCAACCAATTCAATTATT | ACAATGCTGTGCAGATCGATTT | CCGACATGACAAAAGCTATTGCTGGTGA |

| Spy0385 | CGCAAACGTGATTATTTACAAGTGTT | TTTCCAATCTTTTAACCACTTCTTGG | TCTGACTTCGGCCGCATCTTTAACAAAGA |

| gyrA | CGACTTGTCTGAACGCCAAA | TTATCACGTTCCAAACCAGTCAA | CGACGCAAACGCATATCCAAAATAGCTTG |

Covalently linked at the 5′ end to 5-carboxyfluorescein and at the 3′ end to N, N, N-tetramethyl-6-carboxyrhodamine.

Bacterial cell surface localization of proteins assessed by flow cytometric analysis.

Strain MGAS5005 was grown in THY and harvested at an OD600 of 0.4. The bacteria were washed twice with pyrogen-free Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Sigma), pH 7.2, and suspended in 2% fetal bovine serum in DPBS (FBS-DPBS) to 107 CFU/ml. A purified polyclonal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody specific for HtsA, MtsA, or Spy0385 or an anti-Sla control antibody (each at 0.05 μg in 100 μl of FBS-DPBS) was added to 100 μl of bacterial suspension, the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min, and the cells were washed once with FBS-DPBS. The samples were incubated on ice for 30 min with phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.) at a dilution of 1 to 500 in FBS-DPBS, washed once with FBS-DPBS, and analyzed with a FACScaliber flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, Calif.).

RESULTS

Putative ABC transporters for acquisition of heme and metal ions.

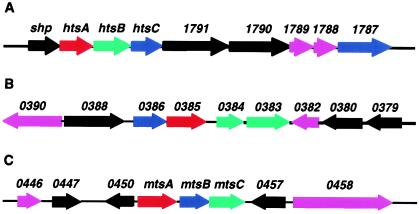

ABC type transporters consist of a solute-binding lipoprotein, one or two membrane proteins (permeases), and an ATPase which are encoded by genes organized into an operon. They transport nutrients across the cytoplasmic membrane (16). Lipoproteins are a major class of extracellular proteins which have type II secretion signal sequences at the amino terminus (31). Proteins with a secretion signal sequence display a typical pattern of a hydrophilic region followed by a hydrophobic region at the amino terminus in hydrophilicity plot analysis. Analysis of an available GAS M1 genome (10) identified 123 open reading frames (ORFs) encoding proteins with this type of pattern. Inferred proteins encoded by these ORFs include 30 proteins with type II secretion signal sequences or putative lipoproteins. Fifteen of the 30 putative lipoproteins are components of putative ABC transporters (data not shown). Three of these putative transporters may participate in iron acquisition (Fig. 1), including htsA (spy1795), htsB (spy1794), and htsC (spy1793) (21); spy0383, spy0384, spy0385, and spy0386 (28); and mtsA (spy0453), mtsB (spy0454), and mtsC (spy0456) (18). The MtsA protein has been shown to have broad specificity for metal ions (18). shp is immediately upstream of htsA and encodes a cell surface heme-binding protein (21).

FIG. 1.

Chromosomal contexts of the 10-kb regions containing genes encoding three putative ABC transporters which may participate in iron acquisition in GAS. Red arrow, lipoprotein gene; blue arrow, ATP-binding protein gene; green arrow, permease gene; pink arrow, hypothetical protein of unknown function black arrow, protein with known or inferred function. Above each arrow is the spy number assigned to the corresponding ORF in the M1 genome sequence (10). (A) ORFs around the htsABC transporter. Known or inferred functions are as follows: shp, heme-binding protein; 1791 and 1790, transporter proteins with transmembrane and ATP-binding domains. (B) ORFs around the spy0386-to-spy0383 transporter. Inferred functions are as follows: 0388, UDP-MurNac-tripeptide synthetase; 0380, manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase; 0379, pyruvate-formate lyase activating enzyme. (C) ORFs around the mtsABC transporter. Inferred functions are as follows: 0447, 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase; 0450, metal-dependent transcriptional regulator; 0457, peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase.

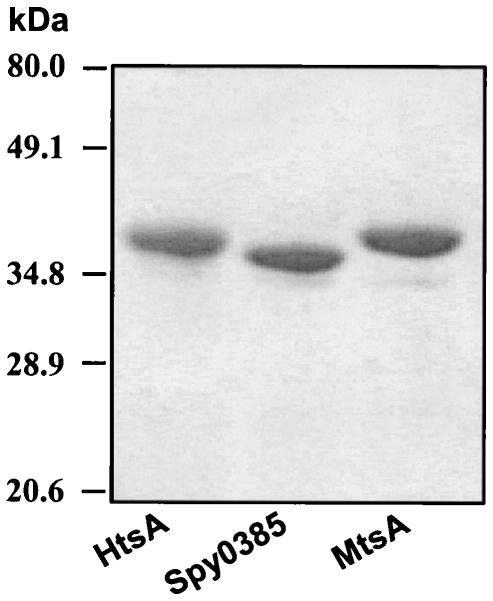

Recombinant proteins.

Recombinant plasmids were constructed to produce mature HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385. MtsA without a His tag was overexpressed, but tag-free HtsA and Spy0385 were not expressed. Attachment of 11 amino acid residues, including the six-His tag, to the mature form achieved overexpression of HtsA and Spy0385. The three recombinant proteins were purified to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of purified recombinant HtsA, Spy0385, and MtsA. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

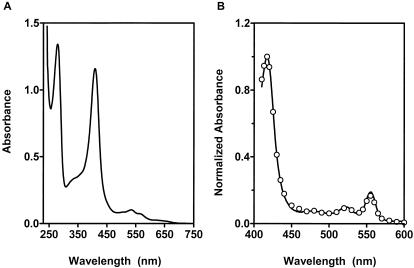

HtsA binds heme.

E. coli expressing HtsA and purified HtsA had an intense red color, indicating that HtsA has an associated chromophore. HtsA had a typical UV-visible absorption spectrum of heme-binding protein with peaks at 275, 370, 417, 530, and 560 nm (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the chromophore is heme. To confirm that heme is the chromophore associated with this protein, we first used a pyridine hemochrome assay (12). Spectral peaks were observed at 418, 524, and 556 nm and were identical to those obtained for purified Mycobacterium tuberculosis KatG (Fig. 3B), a known heme-containing protein, indicating that the bound chromophore is heme. The molar ratio of bound heme to recombinant protein was 0.18, a value indicating that 82% of the protein was in a chromophore-free or apoprotein form.

FIG. 3.

HtsA binds heme. (A) UV-visible absorption spectrum of 50 μM HtsA in THCl. (B) Reductive spectra of pyridine hemochrome derived from HtsA (solid curve) and purified recombinant M. tuberculosis KatG (open circles) obtained as described in Materials and Methods. The spectra were normalized for comparison.

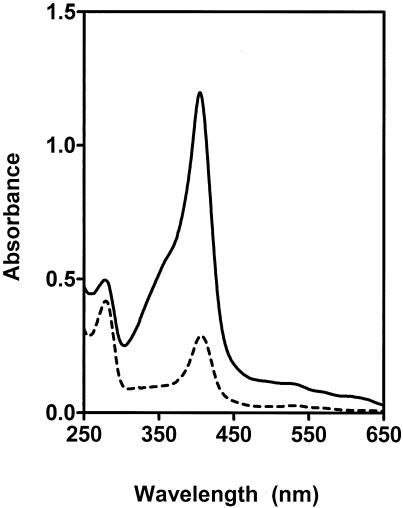

If HtsA binds heme, it should be possible to reconstitute holo-HtsA from heme and apo-HtsA present in the purified HtsA protein. To test this hypothesis, HtsA was first incubated with heme and then separated from free heme by molecular sieve chromatography using a Sephadex G-25 column. The spectra of HtsA with and without holoprotein reconstitution are presented in Fig. 4. The absorbance of reconstituted HtsA at 408 nm, the Soret absorption peak of bound heme, was about 4 times greater than that of untreated HtsA at the same protein concentration. As assessed by the pyridine hemochrome assay, reconstituted HtsA had 1.04 bound heme molecules per protein molecule, compared with 0.18 for untreated HtsA. These results indicate that holo-HtsA was reconstituted from heme and apo-HtsA, and they unambiguously demonstrate that HtsA binds heme in a 1:1 stoichiometry.

FIG. 4.

Reconstitution of holo-HtsA. Purified HtsA, 82% of which was in apo-HtsA form, was incubated with heme, and the protein was separated from free heme by gel filtration using a Sephadex G-25 column. Presented are the optical absorption spectra of the untreated (dashed curve) and treated (solid curve) HtsA samples, both at 10 μM. The absorption peak at 408 nm is the Soret absorption peak of the bound heme.

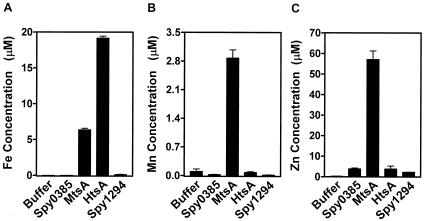

Levels of iron, manganese, and zinc in HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385 measured by ICP-MS.

To further confirm that HtsA binds heme and to obtain preliminary information about the substrate specificity of HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385, the levels of iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), and zinc (Zn) contained in each protein were determined by ICP-MS. The buffer contained little Fe, Mn, and Zn (Fig. 5). The negative-control protein (Spy1294 containing the His tag) contained levels of Fe and Mn similar to those in the buffer but a higher level of Zn (Fig. 5), presumably due to the presence of the His tag. HtsA, at a concentration of 100 μM, contained 19.3 μM iron (Fig. 5A), a value consistent with the heme content (18.6 μM). HtsA, which contained the His tag, had levels of Mn and Zn similar to those of the negative-control protein (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting that HtsA does not bind Mn2+ and Zn2+. MtsA at 100 μM contained 57.1 μM Zn, 6.4 μM Fe, and 2.9 μM Mn (Fig. 5), confirming a previous observation that MtsA binds Fe3+ and Zn2+ (18) and suggesting that MtsA can bind Mn2+. Surprisingly, Spy0385 did not bind Fe, Mn, or Zn ions (Fig. 5).

FIG.5.

Levels of iron, manganese, and zinc in purified Spy0385, MtsA, and HtsA proteins as measured by ICP-MS. Shown are concentrations of iron (A), manganese (B), and zinc (C) in buffer (THCl), Spy0385, MtsA, HtsA, and the negative-control protein Spy1294 (putative maltose/maltodextrin binding protein), each at 100 μM in the buffer.

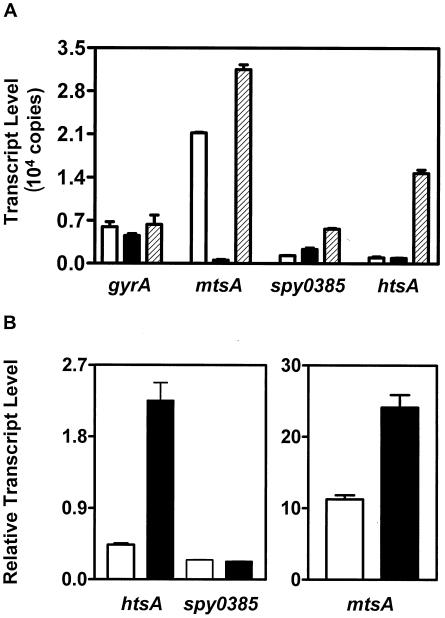

Transcription of spy0385, mtsA, and htsA.

Up- or down-regulation of gene transcription in response to designed conditions has been used widely to identify gene functions and/or support the assignment of gene functions. To compare the relative transcript levels and gain insight into whether the putative transporters are involved in the supply of metal cations, TaqMan analysis was used to assess the transcript levels of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385 and the effects of metal cation-restricted growth conditions on their transcription. In GAS grown in THY which had enough metal cations to support GAS growth, mtsA had high transcript levels while spy0385 and htsA transcript levels were about 5% that of mtsA and 18% that of gyrA (Fig. 6A). In GAS grown in DTHYM which was iron depleted but supplemented with 0.4 mM (each) CaCl2, MgCl2, MnCl2, and ZnCl2, the level of the mtsA transcript decreased 39-fold from that in THY. Meanwhile, the level of the spy0385 transcript increased by 80% and the level of the htsA transcript decreased by 8.7% relative to those in THY (Fig. 6A). Apparently, high levels of one or more of the supplemented metal cations depressed mtsA transcription. To investigate whether metal cation-depleted conditions affect the transcription of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385, the gene transcripts were also quantitated in GAS grown in DTHYMg in which metal cations were removed and 60 μM MgCl2 was added. The levels of mtsA, spy0385, and htsA transcripts in DTHYMg increased by 49, 336, and 1,400%, respectively, over those in THY (Fig. 6A). The gyrA transcript remained at similar levels in GAS grown in THY, DTHYM, and DTHYMg. These results suggest that the transporters containing HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385 supply metal cations, and they indicate the existence of a complex and integrated network for the transcriptional regulation of these genes.

FIG.6.

(A) Effects of growth conditions on transcription of the gyrA, htsA, mtsA, and spy0385 genes. TaqMan assays were carried out with RNA isolated from GAS grown to an OD600 of 0.2 in metal cation-replete THY (open bars), Fe3+-depleted and Ca2+-, Zn2+-, Mn2+-, and Mg2+-replete DTHYM (solid bars), or Fe3+-, Ca2+-, Zn2+-, and Mn2+-depleted DTHYMg (hatched bars). The mean copy number of each indicated gene transcript in 30 ng of total RNA is shown. Error bars, standard deviations. (B) TaqMan analysis of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385 transcription in GAS grown in THY (open bars) or heparinized human blood (solid bars). GAS bacteria were harvested from THY at an OD600 of 0.4 or from human blood after a 4-h incubation. Levels of gene transcripts were normalized to the level of the transcript derived from the gyrA gene. Data are means ± standard deviations of triplicate measurements.

Transcription of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385 in GAS grown in human blood.

To further investigate the regulation of htsA transcription and to compare the relative levels of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385 transcripts in vitro and ex vivo, the transcripts were quantitated by TaqMan analysis. GAS grown in human blood had 5 and 2.5 times higher levels of htsA and mtsA transcripts, respectively, than bacteria grown in THY (Fig. 6B). Levels of spy0385 transcript under the two growth conditions were comparable (Fig. 6B). These results indicate that transcription of htsA and mtsA was up-regulated in GAS grown in human blood relative to that of GAS grown in THY.

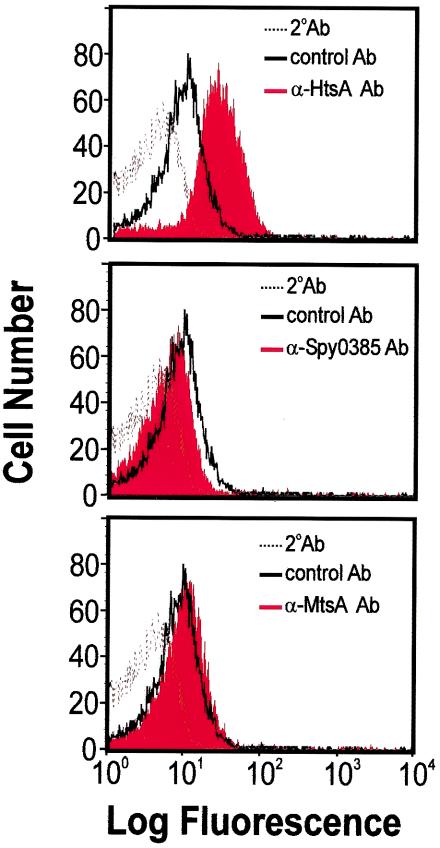

Cell surface expression of HtsA.

Iron acquisition systems are targets of vaccine research for many pathogenic bacteria. Cell surface exposure and accessibility to specific antibodies is one of the criteria for a successful vaccine candidate. To narrow our focus in future studies on GAS vaccine development, we used flow cytometry analysis to determine if HtsA, MtsA, and Spy0385 are located on the GAS cell surface. Only the antibody specific for HtsA recognized protein on the GAS surface (Fig. 7), indicating that HtsA is surface exposed.

FIG. 7.

Assessment of cell surface location of HtsA (top), Spy0385 (center), and MtsA (bottom) by flow cytometry. MGAS5005 (serotype M1) cells harvested at an OD600 of 0.4 were treated with a specific rabbit polyclonal antibody (red histograms) or a control rabbit anti-Sla antibody (histograms with solid black lines), stained with a phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (histograms with dotted lines), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

DISCUSSION

Both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens utilize specific ABC transporters to transport heme across the cytoplasmic membrane, and lipoprotein components of heme-specific ABC transporters have the ability to bind heme (8, 23, 24, 29, 30). In this study, we found that recombinant HtsA, the lipoprotein component of HtsABC of GAS, has an associated chromophore. The features of its optical absorption spectrum and analyses of HtsA by a pyridine hemochrome assay and ICP-MS indicated that the bound chromophore is heme. Moreover, reconstitution of holo-HtsA from apo-HtsA and heme conclusively demonstrated that HtsA binds heme in a 1:1 stoichiometry. These results suggest that HtsABC is an ABC transporter for heme uptake in GAS. The M1 GAS genome (10) encodes 15 putative ABC transporters. We have expressed the recombinant mature form of the lipoproteins for 13 of the 15 transporters in a soluble form in E. coli and purified 9 of the 13 proteins. E. coli overexpressing these proteins, excluding HtsA, did not have an intense red color, and the purified proteins, except for HtsA, did not have an associated chromophore (unpublished data), suggesting that 12 of the 13 proteins do not bind heme. One of the 2 remaining (out of 15) putative ABC transporters is a putative amino acid transporter, and the other has no homology with known iron or heme transporters. Therefore, HtsABC is likely the only ABC transporter that may participate in heme acquisition in GAS.

Gram-negative pathogens transport heme across the outer membrane into the periplasmic space through outer membrane heme-sequestering receptors, and the transport requires TonB, ExbB, and ExbD (20), which presumably use the proton motive force of the cytoplasmic membrane to drive the transport (3). Gram-positive pathogens do not need the TonB system. However, cell surface proteins in addition to ABC transporters are involved in heme acquisition. For example, cell wall-anchored proteins are part of the heme acquisition machinery in Staphylococcus aureus (23). A streptococcal cell surface heme-binding protein, Shp, has also been identified (21). The shp gene is cotranscribed with eight downstream genes (21), including htsABC. Subsequently, Bates et al. (1) reported that shr, the ORF immediately upstream of shp, is also cotranscribed with shp and that recombinant Shr and HtsA (which they named SiaA) can bind hemoglobin. HtsA is localized on the cell surface. HtsA could bind host hemoproteins as a receptor, as proposed by Bates et al. (1), to sequester heme from the bound hemoproteins and deliver heme to the permease HtsB. Heme in host proteins could be extracted by Shp and Shr and relayed to HtsA. We are currently in the process of investigating whether Shp and HtsABC are essential for heme acquisition in GAS and elucidating the molecular mechanism of the heme acquisition process.

The transcription of mtsA, spy0385, and especially htsA is up-regulated under metal cation-depleted conditions, suggesting their roles in the acquisition of iron and/or other metal cations. The transcription of these genes is apparently regulated by different unknown transcription regulators. Metal cation-restricted conditions up-regulated the transcription of all three genes. Iron-depleted and Ca2+-, Zn2+-, Mn2+-, and Mg2+-replete conditions dramatically depressed mtsA transcription, while completely and partially abolishing, respectively, the up-regulation of htsA and spy0385 transcription induced under metal cation-depleted conditions. Furthermore, the transcription of htsA and that of spy0385 responded differently when growth conditions were changed to human blood from THY. Our results also suggest that the unknown transcription regulators belong to an integrated network coordinately responding to the levels of various metal cations. We are currently in the process of identifying the metal ion(s) responsible for depressing mtsA transcription and reversing the up-regulation of htsA transcription induced under metal cation-depleted conditions in an effort to reveal the network regulating the transcription of htsA, mtsA, and spy0385.

ICP-MS analysis confirmed the finding of Janulczyk et al. (18) that MtsA binds Zn2+ and Fe3+. In addition, we detected the binding of Mn2+ by MtsA. It should be noted that MtsA shares 76.3 and 75.2% amino acid sequence identities with the lipoprotein components PsaA (GenBank accession no. AF459738) and ScaA (GenBank accession no. L11577) of manganese transporters in Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus gordonii, respectively. As discussed above, mtsA transcription was down-regulated under iron-depleted conditions. Our findings support the idea that MtsABC transports a cation other than iron under physiological conditions (4). Surprisingly, recombinant Spy0385 did not bind Fe, Zn, or Mn ions. Since iron-restricted conditions enhance spy0385 transcription, the Spy0383-to-Spy0386 transporter is likely involved in iron acquisition but is unlikely to target free Fe3+. Our preliminary data suggest that Spy0385 binds ferrichrome, implying that Spy0383 to Spy0386 may be involved in the acquisition of ferrisiderophore complexes. Although GAS is not known to produce siderophores, and GAS genomes (2, 10, 27) do not have homologues of siderophore production systems, GAS could use the Spy0383-to-Spy0386 transporter to acquire iron by using siderophores produced by other bacteria in the pharynx, the most common site of GAS infection. The iron level in HtsA was similar to the heme content, consistent with the conclusion that HtsA binds heme. GAS is a hemolytic pathogen causing acute inflammatory infections, and hemoproteins released from host cells by GAS should be abundant at both noninvasive and invasive infection sites. In vitro studies indicate that heme or hemoproteins, but not iron-loaded transferrin, support in vitro GAS growth under iron-depleted conditions (9). Taken together, heme is likely the most important iron source for GAS in vivo, and thus, HtsABC is likely an important ABC transporter for iron acquisition in GAS.

There are several indications from the results of flow cytometric analysis that HtsA, but not MtsA or Spy0385, is accessible to specific antibodies. HtsA is cell surface exposed, whereas MtsA and Spy0385 may be buried inside the cell wall. The possible location of these proteins inside the cell wall may be dictated by their substrates. The substrates of MtsA and Spy0385 may be small enough to diffuse freely inside the cell wall, whereas heme, the substrate of HtsA, is usually in complexes with host proteins or extracted from host proteins by GAS cell surface proteins, and cell surface exposure of HtsA may be essential for the acquisition of heme from host and/or GAS hemoproteins. PsaA and ScaA are suggested to be adhesins (19). Due to limited exposure on the cell surface, MtsA, which is homologous to PsaA and ScaA, may not function as an adhesin. If HtsABC is crucial for iron acquisition and virulence in GAS, HtsA may be a vaccine candidate.

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Bates, C. S., G. E. Montanez, C. R. Woods, R. M. Vincent, and Z. Eichenbaum. 2003. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes operon involved in binding of hemoproteins and acquisition of iron. Infect. Immun. 71:1042-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beres, S. B., G. L. Sylva, K. D. Barbian, B. Lei, J. S. Hoff, N. D. Mammarella, M. Liu, J. C. Smoot, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, J. K. McCormick, D. Y. M. Leung, P. M. Schlievert, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence of a serotype M3 strain of group A Streptococcus: phage-encoded toxins, the high-virulence phenotype, and clone emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:10078-10083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradbeer, C. 1993. The proton motive force drives the outer membrane transport of cobalamin in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:3146-3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, J. S., and D. W., Holden. 2002. Iron acquisition by Gram-positive bacterial pathogens. Microbes Infect. 4:1149-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaussee, M. S., R. O. Watson, J. C. Smoot, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822-831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, B. P. C., and T. Hai. 1994. Expression vectors for affinity purification and radiolabeling of proteins using Escherichia coli as host. Gene 139:73-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham, M. W. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drazek, E. S., C. A. Hammack, and M. P. Schmitt. 2000. Corynebacterium diphtheriae genes required for acquisition of iron from haemin and haemoglobin are homologous to ABC haemin transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 36:68-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichenbaum, Z., E. Muller, S. A. Morse, and J. R. Scott. 1996. Acquisition of iron from host proteins by the group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 64:5428-5429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferretti, J. J., W. M. McShan, D. Ajdic, D. J. Savic, G. Savic, K. Lyon, C. Primeaux, S. Sezate, A. N. Suvorov, S. Kenton, H. S. Lai, S. P. Lin, Y. Qian, H. G. Jia, F. Z. Najar, Q. Ren, H. Zhu, L. Song, J. White, X. Yuan, S. W. Clifton, B. A. Roe, and R. McLaughlin. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4658-4663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis, R. T., Jr., J. W. Booth, and R. R. Becker. 1985. Uptake of iron from hemoglobin and the haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex by hemolytic bacteria. Int. J. Biochem. 17:767-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuhrhop, J. H., and K. M. Smith. 1975. Laboratory methods, p. 804-807. In K. M. Smith (ed.), Porphyrins and metalloporphyrins. Elsevier Publishing Co., New York, N.Y.

- 13.Genco, C. A., and D. W. Dixon. 2001. Emerging strategies in microbial haem capture. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghigo, J.-M., S. Letoffe, and C. Wandersman. 1997. A new type of hemophore-dependent heme acquisition system of Serratia marcescens reconstituted in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:3572-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths, E., and P. Williams. 1999. The iron-uptake systems of pathogenic bacteria, fungi and protozoa, p. 87-212. In J. J. Bullen and E. Griffiths (ed.), Iron and infection: molecular, physiological and clinical aspects. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 16.Higgins, C. F. 1992. ABC transporters: from microorganisms to man. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 8:67-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoe, N. P., K. Nakashima, D. Grigsby, X. Pan, S. J. Dou, S. Naidich, M. Garcia, E. Kahn, D. Bergmire-Sweat, and J. M. Musser. 1999. Rapid molecular genetic subtyping of serotype M1 group A Streptococcus strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:254-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janulczyk, R., J. Pallon, and L. Bjorck. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Streptococcus pyogenes ABC transporter with multiple specificity for metal cations. Mol. Microbiol. 34:596-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson, J. F. 1994. Cell surface protein receptors in oral streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:133-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klebba, P. E., J. M. Rutz, J. Liu, and C. K. Murphy. 1993. Mechanisms of TonB-catalyzed iron transport through the enteric bacterial cell envelope. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 25:603-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lei, B., L. M. Smoot, H. M. Menning, J. M. Voyich, S. V. Kala, F. R. DeLeo, S. D. Reid, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Identification and characterization of a novel heme-associated cell surface protein made by Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:4494-4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mazmanian, S. K., E. P. Skaar, A. H. Gaspar, M. Humayun, P. Gornicki, J. Jelenska, A. Joachmiak, D. M. Missiakas, and O. Schneewind. 2003. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science 299:906-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Occhino, D. A., E. E. Wyckoff, D. P. Henderson, T. J. Wrona, and S. M. Payne. 1998. Vibrio cholerae iron transport: haem transport genes are linked to one of two sets of tonB, exbB, exbD genes. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1493-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otto, B. R., A. M. J. J. Verweij-van Vught, and D. M. MacLaren. 1992. Transferrins and heme-compounds as iron sources for pathogenic bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 18:217-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schryvers, A. B., and I. Stojiljkovic. 1999. Iron acquisition systems in the pathogenic Neisseria. Mol. Microbiol. 32:1117-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smoot, J. C., K. D. Barbian, J. J. Van Gompel, L. M. Smoot, M. S. Chaussee, G. L. Sylva, D. E. Sturdevant, S. M. Mackie, S. F. Porcella, L. D. Parkins, S. B. Beres, D. S. Campell, T. M. Smith, Q. Zhang, V. Kapur, J. A. Daly, L. G. Veasy, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Genome sequence and comparative microarray analysis of serotype M18 group A Streptococcus strains associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:4668-4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smoot, L. M., J. C. Smoot, M. R. Graham, G. A. Somerville, D. E. Sturdevant, C. A. Migliaccio, G. L. Sylva, and J. M. Musser. 2001. Global differential gene expression in response to growth temperature alteration in group A Streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:10416-10421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojiljkovic, I., and K. Hantke. 1994. Transport of haemin across the cytoplasmic membrane through a haemin-specific periplasmic binding-protein-dependent transport system in Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 13:719-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson, J. M., H. A. Jones, and R. D. Perry. 1999. Molecular characterization of the hemin uptake locus (hmu) from Yersinia pestis and analysis of hmu mutants for hemin and hemoprotein utilization. Infect. Immun. 67:3879-3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Heijne, G. 1989. The structure of signal peptides from bacterial lipoproteins. Protein Eng. 2:531-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberg, E. D. 1974. Iron and susceptibility to infectious disease. Science 184:952-956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinberg, E. D. 1990. Cellular iron metabolism in health and disease. Drug Metab. Rev. 22:532-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]