Abstract

Ammonia production is of great importance for the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori as a nitrogen source, as a compound protecting against gastric acidity, and as a cytotoxic molecule. In addition to urease, H. pylori possesses two aliphatic amidases responsible for ammonia production: AmiE, a classical amidase, and AmiF, a new type of formamidase. Both enzymes are part of a regulatory network consisting of nitrogen metabolism enzymes, including urease and arginase. We examined the role of the H. pylori amidases in vivo by testing the gastric colonization of mice with H. pylori SS1 strains carrying mutations in amiE and/or amiF and in coinfection experiments with wild-type and double mutant strains. A new cassette conferring resistance to gentamicin was used in addition to the kanamycin cassette to construct the double mutation in strain SS1. Our data indicate that the amidases are not essential for colonization of mice. The search for amiE and amiF genes in 53 H. pylori strains from different geographic origins indicated the presence of both genes in all these genomes. We tested for the presence of the amiE and amiF genes and for amidase and formamidase activities in eleven Helicobacter species. Among the gastric species, H. acinonychis possessed both amiE and amiF, H. felis carried only amiF, and H. mustelae was devoid of amidases. H. muridarum, which can colonize both mouse intestine and stomach, was the only enterohepatic species to contain amiE. Phylogenetic trees based upon the sequences of H. pylori amiE and amiF genes and their respective homologs from other organisms as well as the amidase gene distribution among Helicobacter species are strongly suggestive of amidase acquisition by horizontal gene transfer. Since amidases are found only in Helicobacter species able to colonize the stomach, their acquisition might be related to selective pressure in this particular gastric environment.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacterium that colonizes the gastric mucosa of humans (11, 36). It is the etiologic agent of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcers and is a risk factor for the development of gastric cancer (14). In H. pylori, nitrogen metabolism is strongly dependent on ammonia production, as illustrated by the absence of the GOGAT assimilation enzyme (glutamate synthase), which is characteristic of an organism in which ammonia is never limiting (9). One specific feature of H. pylori is the link between ammonia production and its capacity to resist strong acidity. Urease, which is very abundant in H. pylori, produces ammonia and is essential for the acid resistance of this bacterium (7, 13). Several studies have suggested that the large amounts of ammonia produced by H. pylori are also responsible for tissue damage during colonization. The long-term administration of ammonia induces mucosal atrophy in the stomachs of rats (51), and the ammonia generated by H. pylori accelerates cytokine-induced apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells (25). H. pylori also possesses other ammonia-producing enzymes, including deaminases, deamidases (both found in many bacteria), and, more unusually, two aliphatic amidases, AmiE and AmiF. Aliphatic amidases (EC 3.5.1.4) are enzymes that hydrolyze short-chain amides to produce ammonia and the corresponding organic acid. The finding of aliphatic amidases in H. pylori was unexpected, as these enzymes had been described only in bacteria that spend at least part of their life cycles in the environment (Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Rhodococcus erythropolis). In previous studies (42, 43), the two amidases found in H. pylori were identified and characterized. The first amidase, AmiE, is a typical aliphatic amidase, showing 75% sequence identity with its orthologs and presenting characteristic substrate specificity. In vitro, AmiE hydrolyzes acrylamide, acetamide, and propionamide very efficiently but is not active on formamide or urea (42). H. pylori is the first organism in which a second amidase has been found; this enzyme, designated AmiF, displays 34% sequence identity with AmiE proteins. AmiF displays unexpected substrate specificity, as it is active only on formamide, the shortest amide (42). AmiF is the first formamidase (EC 3.5.1.49) described to belong to the aliphatic amidase enzyme family. A conserved cysteine residue within the active site has been identified for both enzymes (42). Despite this knowledge of the amidases of H. pylori, the role of these enzymes in vivo and the nature and origin of the natural substrate of AmiE remain unclear. It is difficult to identify this substrate, as it can be generated either in the gastric juice or as a by-product of intracellular metabolism. Interestingly, we found that the production of AmiE and AmiF is dependent on the activity of other enzymes involved in nitrogen metabolism, urease and arginase, respectively (42). These data strongly suggest that the amidases are involved in nitrogen metabolism in H. pylori and that their synthesis is regulated to maintain the intracellular nitrogen balance. AmiE is a highly produced protein. Antibodies specifically recognizing this protein, but not AmiF, are present in the sera of a large proportion of patients (21 out of 26 tested) (43; unpublished data). Immunoproteomic studies also confirmed the recognition of AmiE by patient sera. Serum samples from patients with gastric cancer were more frequently immunoreactive (22).

The aims of this study were (i) to improve our understanding of the role of amidases in H. pylori by using a mouse model and (ii) to examine the distribution of the amidases in the Helicobacter genus to allow us to determine whether there is a correlation between these enzymes and the habitat of the Helicobacter species tested (gastric, hepatic, or enteric). The distribution of the amiE and amiF genes in H. pylori and in the Helicobacter species led us to propose a model for the acquisition of these genes in relation to their colonization site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

E. coli strain MC1061 (5) was used as a host for the preparation of the plasmids used to transform H. pylori. E. coli strains were grown at 37°C on solid or liquid Luria-Bertani medium (35). Antibiotics for the selection of recombinant E. coli strains were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 20 μg ml−1; tetracycline, 10 μg ml−1; gentamicin, 30 μg ml−1, and carbenicillin, 100 μg ml−1. The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Helicobacter strains were grown on blood agar base 2 plates (Oxoid) supplemented with 10% defibrinated horse blood and with an antibiotic and fungicide mix consisting of vancomycin (final concentration, 10 μg ml−1), polymyxin B (2.5 IU liter−1), trimethoprim (5 μg ml−1), and fungizone (2.5 μg ml−1). The plates were incubated for 24 to 48 h at 37°C in microaerobic conditions. For the selection of SS1 H. pylori transformants (four to five days of growth), kanamycin and gentamicin were added to the growth medium at concentrations of 20 μg ml−1 and 5 μg ml−1, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristic(s) or natural host | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| MC1061 | F′ araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7696 galE15 galK16, Δ(lacX74) rpsL hsdR2 mcrA mcrB1 | 5 |

| H. pylori | Human | |

| N6 | Parental strain | 16 |

| 26695 | Parental strain | 49 |

| SS1 | Parental strain | 32 |

| SS1-444a | SS1-amiEΩaac(3)-IV | This work |

| SS1-437b | SS1-amiFΩaphA-3 | This work |

| SS1-444a-437b | SS1-amiEΩaac(3)IVamiFΩaphA-3 | This work |

| H. pylori (pluri-ethnic collection) | Human | D. E. Berg |

| H. acinonychis ATCC 51101 | Cheetah | 12; via CIPa |

| H. felis CS1, ATCC 49179 | Cat, dog | 37; via R. Ferrero |

| H. mustelae R85-13-6P, ATCC 43772 | Ferret | 19; via CIP |

| H. pametensis B9A, ATCC 51478 | Bird, swine | 10; via CIP |

| H. cinaedi 165, ATCC 35683 | Human, hamster | 52; via CIP |

| H. bilis MIT Hb1, ATCC 51630 | Mouse, dog, human | 20; via CIP |

| H. canis ATCC 51401 | Dog, human | 46; via CIP |

| H. muridarum | Mouse, rat | |

| ST1, ATCC 49282 | 33; via CIP | |

| ST2 | 33; via J. L. O'Rourke | |

| ST3 | 33; via J. L. O'Rourke | |

| ST5 | 33; via J. L. O'Rourke | |

| H. hepaticus ATCC 51449 | Mouse | 18; via J. G. Fox |

| H. fenelliae 231, ATCC 35684 | Human | 50; via CIP |

CIP, Collection of the Institut Pasteur.

Molecular techniques, PCR, sequencing, and Southern blotting.

Standard procedures were used for small-scale plasmid preparation, endonuclease digestion, ligation, and agarose gel electrophoresis and for the elution of DNA fragments from agarose gels (41). Midi or maxi QIAGEN columns were used for large-scale plasmid preparations. The QIAamp DNA extraction kit (QIAGEN) was used to extract chromosomal DNA from Helicobacter species. PCR was carried out according to the manufacturer's recommendations by using the Taq DNA polymerase kit (Amersham). Sequencing was performed on an ABI 310 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (29).

The chromosomal DNA extracted from the collection of H. pylori strains from different geographic origins was amplified by PCR with primers H46 and H58 for the amiE gene and primers H69 and H70 for the amiF gene (Table 2). The procedure comprised an initial denaturation step at 94°C (2′) followed by 30 cycles of 30 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The absence of PCR cross-reaction on the cognate amidase gene was verified with each pair of primers by using as a template E. coli plasmids in which the entire H. pylori amiE or amiF gene was cloned (pILL417 and pILL439b, respectively) (42).

TABLE 2.

Designations and nucleotide sequences of primers used for PCR amplification and plasmid construction

| Target gene | Primera | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′)b |

|---|---|---|

| amiE | H46(f) | CCTTATAACACTTTGATTCTTGTC |

| H58(r) | CCGCTACATAACATTGATTGGCCC | |

| H49(r) | CAAGCCCTTAGGCCCATCAACC | |

| H59(f) | CGGGATCCAGACATGGAGATATTAGTAGC | |

| H37(r) | CCAiAT(C/T)TCiGG(A/G)TA(A/G)ATiCC(A/G)TC(A/G)TC(A/G)C | |

| amiF | H69(f) | CGggatccATGGGAAGTATCGGTAGTATGGGC |

| H70(r) | GgaattcGAATCATGCCGTCATGGCAAATGCAC | |

| OI11(r) | GGAATTCATTTCCCCGGTTACAATCTCCCA | |

| H89(r) | CACGCTCACGGTATACATC | |

| 16S RNA | H276(f) | CTATGACGGGTATCCGGC |

| H676(r) | ATTCCACCTACCTCTCCCA | |

| acc(3)-IV | H121 | GGCTTTTCGCCATTCGTATTGC |

| H122 | GACGTTGGAGGGGCAAGGTCG | |

| aphA-3 | H50 | CCGGTGATATTCTCATTTTAGCC |

| H17 | TTTGACTTACTGGGGATCAAGCCTG |

f, forward primer; r, reverse primer.

Lowercase letters indicate BamHI (H69) and EcoRI (H70) restriction sites. For primer H37, two residues at the same position indicate that the oligonucleotide preparation contained a mixture of both types of molecule; “i” corresponds to inosine.

Southern blot experiments were performed by using a low-stringency hybridization protocol (hybridization at 42°C in the presence of 30% formamide) (41). Genomic DNA was digested overnight with the HindIII restriction enzyme. Gene-specific probes with chromosomal DNA from strain 26695 were obtained by PCR by using primer pair H59-H37 for amiE and primer pair H69-H89 for amiF; the probes for each gene were 522- and 654-bp long, respectively (Table 2). The probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci mmol−1) by using the Megaprime random labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). As a control, the same membranes were hybridized with a 16S rRNA gene probe (a 375-bp-long PCR product was generated with H276f, H676r, and H. pylori DNA) (Table 2) that recognized the corresponding genes in all the Helicobacter species.

Construction of plasmids and H. pylori mutants.

As a prerequisite for the construction of a double mutation in strain SS1, we developed a new cassette suitable for insertional mutagenesis in this genetic background. Indeed, we were not able to select SS1 mutants with amiE interrupted by a cat cassette (encoding chloramphenicol acetyltransferase). Therefore, we used for the first time an apramycin-gentamicin resistance cassette originating from the pUC1813apra vector (D. Mazel, unpublished data), a derivative of pUC1813 carrying the aac(3)-IV gene from the pWP7b R-plasmid (3). We verified the sequence of this gene and found that the originally published sequence contained three more base pairs than our sequence (3). Partially corrected versions of the aac(3)-IV sequence are now available in GenBank, but only one (accession number AJ414670) includes all three corrections consistent with our sequence.

pILL444a, amiEΩaac(3)-IV was derived from pILL835 (43) by insertion of an apramycin-gentamicin resistance cassette (a 1-kb SmaI fragment from pUC1813apra) into the amiE gene at the unique SmaI restriction site (Fig. 1). pILL436 is a pBR322 derivative carrying the first 520 bp of amiF amplified with primers H69-H70 (Table 2). pILL437b, amiFΩapha-3 was derived from pILL436 by insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette (a 1.5-kb SmaI fragment from pILL600) (28) into the unique SmaI restriction site situated in the amiF gene (Fig. 1). The H. pylori mutant strains were obtained by natural transformation as previously described (4) with about 2 μg of plasmid DNA prepared on maxi QIAGEN columns. After transformation, gene replacement with the chromosome of strain SS1 was selected on gentamicin for pILL444a or on kanamycin for pILL437b, resulting in the SS1-444a and SS1-437b mutant strains, respectively. The double mutant strain was obtained by transformation of strain SS1-444a by pILL437b and selection on both gentamicin and kanamycin. PCR was used to ensure that the expected allelic exchange events had occurred. The following primer pairs were used: for amiE, H49-H122, H59-H121, and H49-H59, and for amiF, H69-H50, OI11-H17, and H69-OI11 (Table 2).

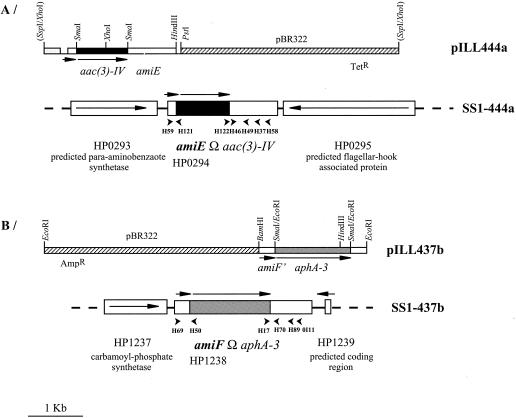

FIG. 1.

Insertional mutations of the amiE and amiF genes in H. pylori SS1. Restriction maps of pILL444a and pILL437b are shown. For each construction, the vector is represented by a hatched box. The genes are indicated by boxes, with arrows indicating the direction of transcription. Tetr and Ampr represent the genes conferring resistance to tetracycline and carbenicillin, respectively. The aac(3)-IV gene confers resistance to gentamicin, and the aphA-3 gene confers resistance to kanamycin. The chromosomal organization of the resulting mutant strains is shown with the adjacent genes. We used specific primers to verify that the genes downstream and upstream of amiE and amiF in strain SS1 were identical to those of the sequenced strain 26695. The small arrowheads indicate the primers used in this study.

Mouse model for colonization.

Wild-type or mutant strains of H. pylori were harvested after 24 h of growth on blood agar plates and suspended in peptone broth. The bacterial concentrations were adjusted to 108 bacteria ml−1 or 109 bacteria ml−1, depending on the experiment; the CFU were subsequently counted precisely. Aliquots (100 μl) of bacteria were administered orogastrically to 10 female NMRI mice (four weeks old; provided by Iffra-Credo) as described previously (17). In each experiment, six mice were inoculated with peptone broth as a negative control. Mice were killed 4 weeks after inoculation. We tested for the presence of H. pylori with a direct urease test performed on half the stomach. The remaining gastric tissues were used for the quantitative culture of H. pylori on blood agar plates in the presence of bacitracin (200 μg ml−1) and nalidixic acid (10 μg ml−1) as described before (17): (i) without antibiotics for the mice infected with the SS1 parental strain, (ii) with 20 μg of kanamycin ml−1 for mice infected with SS1-437b, (iii) with 5 μg of gentamicin ml−1 for mice infected with SS1-444a, (iv) with kanamycin and gentamicin for mice infected with SS1-444a-437b, and (v) on plates without antibiotics plus on plates with both kanamycin and gentamicin for the mixed infections. We confirmed that with the mutant strains the presence of one or two antibiotics did not affect the number of CFU. The wild-type SS1 strain and the single mutants (SS1-437b and SS1-444a) had undergone 21 in vitro subcultures since recovery from the mouse stomach, whereas the double mutant strain (SS1-444a-437b) had undergone 25. This is far below the number of in vitro cultures at which the SS1 strain starts to lose its ability to colonize mice (about 75 passages; R. Ferrero, personal communication). We followed the growth of the mutant strains (single or double mutants) in liquid medium to ensure that their doubling time was identical to that of the parental SS1 strain.

Measurement of urease, amidase and formamidase activities.

Cell extracts prepared as previously described (43) were used to measure urease, amidase, and formamidase activities. Samples (10 to 50 μl) were added to 200 μl of a urea or amide substrate solution (acrylamide, acetamide, or formamide) at a final concentration of 100 mM in 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and 10 mM EDTA. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min; then 400 μl of phenol-nitroprusside and 400 μl of alkaline hypochlorite were added, and the samples were incubated for 6 min at 50°C. Absorbance was then read at 625 nm. The amount of ammonia released was determined from a standard curve. One unit (U) of amidase or formamidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to hydrolyze 1 μmol of amide (corresponding to the formation of 1 μmol of ammonia) per min per mg of total protein. One unit of urease activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to hydrolyze 1 μmol of urea (producing 2 μmol of ammonia) per min per mg of total protein. Protein concentration was determined with a commercial version of the Bradford assay (Sigma Chemicals) by using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Phylogenetic analysis of the amiE and amiF genes.

Sequences of amiE and amiF were retrieved from the EMBL (Cambridge, United Kingdom) and GenBank (Bethesda, Md.) databases. The amiF sequences of Bacillus anthracis and Desulfovibrio vulgaris were obtained from the respective unfinished genome sequences of the Institute of Genome Research. The amiE and amiF sequence data sets were treated separately. Sequences were first aligned by using Clustal W (24). The initial alignments were further refined by eye by using the alignment editor of the PAUP* version 4.0 software package (47). Likelihood scores were calculated for 56 different models of evolution by using PAUP*. The likelihood scores were compared by using the hierarchical likelihood ratio test approach through Modeltest version 3.0 (38). The general time reversible model of substitution (39) was selected as the model that best fit both gene data sets. Gamma shape parameters, substitution rate matrices, and nucleotide frequencies were also estimated for each gene by using Modeltest. The improved version of the Neighbor Joining algorithm, BIONJ (21), and the maximum likelihood method were applied under these models and settings to build phylogenetic trees. Maximum parsimony trees were built by heuristic search with a starting tree based on 10 random stepwise additions and using the tree bisection-reconnection branch-swapping option. Statistical significance was evaluated by bootstrap analysis (15) with 100 repeats of bootstrap samplings.

RESULTS

Use of a new apramycin-gentamicin resistance cassette to generate amidase gene mutations in the SS1 strain.

The mouse-adapted H. pylori SS1 strain is widely used for its capacity to colonize mice efficiently and because it is genetically transformable (32, 44). To construct an SS1 mutant strain carrying insertional mutations in both amidase genes, we used a new cassette comprising a gentamicin-apramycin resistance gene, designated aac(3)-IV and originating from the pWP7b R-plasmid (3). This cassette was constructed and validated in different H. pylori strains, including SS1, N6, 26695 (Table 1), J99 (2), X47-2AL (27), and HAS-141 (26). The aac(3)-IV gene was inserted into the amiE gene in both orientations (pILL444a and pILL444b). After its transformation into H. pylori strain SS1 and its selection on gentamicin, we found that allelic exchange occurred only with pILL444a, i.e., when aac(3)-IV was in the same orientation as amiE (Fig. 1). The resulting strain was designated SS1-444a (Fig. 1). This suggests that the aac(3)-IV promoter was not active in H. pylori and that it was expressed only under the control of the amiE promoter in strain SS1-444a.

The same strategy, inserting pILL437b carrying the aphA3 gene into the amiF gene, was used to construct strain SS1-437b (Fig. 1). An SS1 derivative deficient in both amidase genes was constructed by introducing the amiFΩaphA-3 mutation into the SS1-444a [amiEΩaac(3)-IV] strain. This double-mutant SS1 derivative carrying amiEΩaac(3)-IV and amiFΩaphA-3 was designated SS1-444a-437b (Table 1). We ensured that the single mutants lacked AmiE or AmiF activities and that the double mutant lacked AmiE and AmiF activities.

Colonization of the mouse model with amidase-deficient mutants.

We used several different experimental approaches to study the impact of amidase and formamidase activities on the efficiency of mouse colonization by the SS1 strain (Fig. 2). In the first protocol, the inoculation dose was 1 × 108 to 7 × 108 bacteria per mouse. The infecting strains consisted of the single-mutant strains deficient in amiE (SS1-444a) or in amiF (SS1-437b), the double-mutant strain (SS1-444a-437b), and the parental wild-type SS1 strain (positive control). Four weeks after infection, we assessed the bacterial load in the mouse stomach. In these conditions, colonization with the mutant strains was as effective as that with the parental strain, with mean gastric colonization loads of 5 × 104 to 3 × 105 bacteria per g of gastric tissue (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained with amidase-deficient mutants of another mouse-adapted strain, X47-2AL (27) (data not shown).

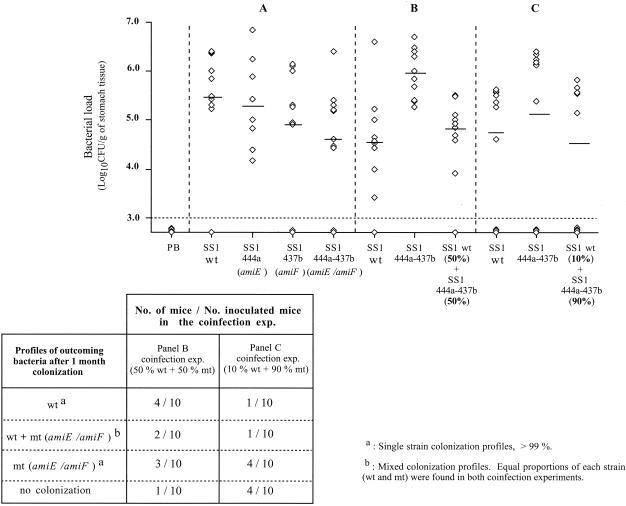

FIG. 2.

Assessment of mouse stomach colonization after inoculation with H. pylori SS1, amidase-negative mutant strains, or a mixture of wild-type and mutant strains. SS1-444a corresponds to the amiE-deficient mutant, SS1-437b corresponds to the amiF mutant, and SS1-444a-437b corresponds to the double mutant strain deficient in both amidases. Panels A, B, and C correspond to three independent experiments. The strains used to inoculate the mice are indicated below the panels. The detection limit of the assay is indicated by the dashed horizontal line. PB corresponds to five control animals inoculated with sterile peptone broth. Each point (indicated by an open diamond) corresponds to the gastric colonization load for one mouse, and the horizontal bars represent the geometric mean for each group of mice. The table presents the results of the two coinfection experiments. wt indicates the wild-type strain, and mt (amiE/amiF) indicates the double mutant. The values in the table correspond to the number of mice presenting a given stomach colonization profile versus the total number of mice tested for the coinfection experiment of panel B or C. For instance, in the panel B coinfection experiment, 4 out of the 10 inoculated mice were infected solely with a wild-type strain.

In a second set of experiments, the inoculation dose was between 4 × 107 and 8 × 107 bacteria per mouse. We compared the outcomes of the infection with the wild-type strain and with the amidase double mutant strain, and we also performed coinfections to examine whether the double mutant strain could be out-competed for colonization by the wild-type strain. We first tested a mixed infection with 50% wild-type strain (4 × 107 bacteria/mouse) and 50% double mutant strain (4 × 107 bacteria/mouse). This test allowed us to determine which of the two strains colonized the mouse stomach and to what extent, based on the kanamycin and gentamicin resistance of the double mutant. In this experiment, we found that the mean colonization load for the double mutant alone was higher than that for the wild-type strain alone (9 × 105 and 4 × 104 bacteria per g of gastric tissue, respectively) (Fig. 2B). Nine of the 10 mice infected with the mixed inoculum were colonized as follows (Fig. 2, table): (i) four mice carried almost exclusively the wild-type strain; (ii) three mice were infected only with the double mutant strain; and (iii) two mice were colonized with a mixed population. The unexpectedly low proportion of mice presenting mixed colonization will be discussed later.

In the last experimental approach (Fig. 2C), the inoculation dose was slightly lower (107 bacteria per mouse). This was probably a limiting dose, as for each infecting strain 3 or 4 of the 10 mice were not infected. The mean colonization loads of the wild type and the double mutant were 4.5 × 104 and 1.5 × 105 bacteria per g of gastric tissue, respectively. In the colonization competition test, we inoculated mice with a mixture of 10% wild-type strain (106 bacteria/mouse) and 90% double mutant strain (9 × 106 bacteria/mouse). Six mice were infected. The double mutant strain was the unique colonizer in four mice, and the wild-type strain was the only colonizer in one case. The last mouse was colonized with a mixture of both strains (Fig. 2, table). The competition index was calculated for the coinfection experiments as previously described (40). This value, which takes into consideration the outcome of the bacterial load for each of the two inoculated strains, showed that in the mouse model the double mutant strain was not at a disadvantage for colonization.

Distribution of the amiE and amiF genes in H. pylori isolates.

Given the great variability and plasticity of the H. pylori genome (1), we investigated whether the amiE and amiF genes were always present together in this species. We tested 53 H. pylori strains from various geographic origins by PCR with amiE-specific primers (H46-H58) (Table 2) and with amiF-specific primers (H69-H70) (Table 2). The size of the corresponding PCR products was 307 bp for amiE and 514 bp for amiF. The strains included 20 strains from Bordeaux in France (which already tested positive in previous studies; see references 42 and 43), 5 from Spain, 5 from Lithuania, 5 from Hong Kong, 5 from India, 5 from South Africa, 4 from Peru, and 4 from Alaska. PCR products of the expected size were obtained in every case, indicating that all strains examined contained both the amiE and amiF genes.

Construction of phylogenetic trees for the amiE and amiF genes.

Helicobacter is the only bacterium from the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts known to possess an aliphatic amidase and a new type of formamidase. This prompted us to investigate the evolutionary origin of these enzymes by establishing phylogenetic trees for these two genes.

As a prerequisite to this analysis, the general time reversible model of substitution was applied to our data. The parameters estimated under this model showed slight differences between base frequencies and between substitution rates among sites of the two genes. Nucleotide frequencies were found to be equal for amiF and heterogeneous for amiE (for A, 0.2609; for C, 0.2541; for G, 0.2839; for T, 0.2011). Both genes showed variable substitution rates over sites, but the extent of rate variation was more apparent for amiE. The alpha shape parameters (used to determine the shape of the gamma distributions of these rates) were 1.0695 and 0.4315 for amiF and amiE, respectively. Thus, the parameters estimated for the two samples of sequences revealed that there were differences in the evolutionary constraints between amiE and amiF.

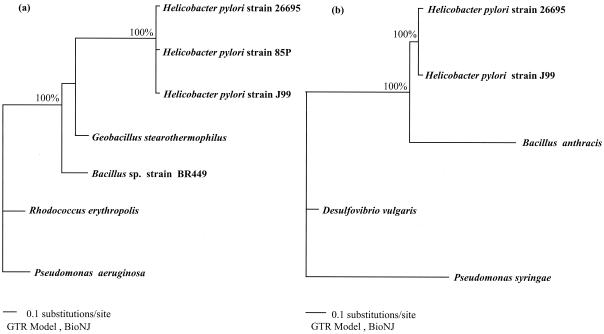

The phylogenetic trees based on the amiE and amiF genes obtained with distance methods are shown in Fig. 3a and b, respectively. The 1,020 and 1,033 unambiguously aligned positions of the amiE and amiF gene sequences, respectively, corresponded to 355 and 221 informative positions under the conditions of parsimony. Whatever the phylogenetic method used, the H. pylori amiE or amiF genes were rooted by genes from low-G+C-content, gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus spp. or Geobacillus stearothermophilus).

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic trees derived from amiE (a) and amiF (b) gene sequence comparisons with the BIONJ method. The percentages are the significant bootstrap values of 100 calculated trees.

Distribution of the amiE and amiF genes and the amidase and formamidase activities among the Helicobacter species.

To gain information on the distribution of the amidases in the Helicobacter genus, we examined gastric and enterohepatic strains that are homogeneously distributed throughout the Helicobacter phylogenetic tree (45) (Fig. 4). The presence of the amiE and amiF genes in the genomes of these Helicobacter species was examined by Southern blotting on chromosomal DNA preparations digested by HindIII by using specific PCR products of the H. pylori amiE and amiF genes as probes. The absence of cross-reaction between the amiE and amiF probes was verified on H. pylori DNA. In addition to the H. pylori strains (N6 and 26695), three gastric species (H. felis, H. acinonychis and H. mustelae) were examined (Table 1). Six enterohepatic Helicobacter species were analyzed (H. pametensis, Helicobacter cinaedi, Helicobacter bilis, Helicobacter canis, Helicobacter muridarum, and H. fennelliae) (Table 1). Information concerning the absence of amiE and amiF from the complete H. hepaticus genome sequence was provided by Suerbaum et al. (46a).

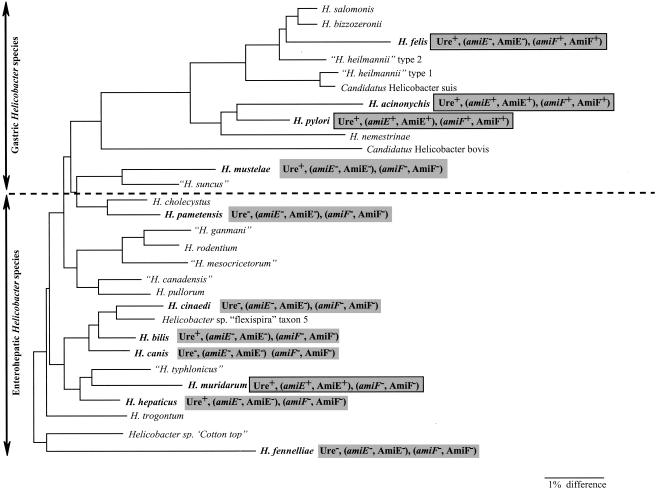

FIG. 4.

Distribution within the Helicobacter phylogenetic tree of amidase activities and the amiE or amiF genes. The 11 Helicobacter species tested are shown in bold. A hatched line separates the gastric species (top) from the enterohepatic species (bottom). The tree (adapted from the work of Solnick and Schauer [45]) contains a total of 28 Helicobacter species and is based on 16S rRNA sequences. The scale bar represents a 1% difference in nucleotide sequence, as determined by measuring the lengths of the horizontal lines connecting two species. The results of our study are indicated in shaded boxes; the black borders indicate that amidase or formamidase was found. The following abbreviations are used: Ure, AmiE, and AmiF for urease activity, AmiE-like activity, and AmiF-like enzyme activities, respectively, and amiE and amiF for the amidase and formamidase gene, respectively.

The results of the Southern blot experiments (data not shown) are presented in Table 3. Both the amiE and amiF genes were found in H. acinonychis and the two H. pylori strains (the positive controls). H. felis was found to contain an amiF-like gene, and H. muridarum was found to contain an amiE-like gene. No hybridization product was detected for the other species examined.

TABLE 3.

Activities of general amidase, formamidase, and urease and presence of the amiE and amiF genes in different Helicobacter species

| Strain | Urease activitya | Result for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General amidase

|

Formamidase

|

||||

| AmiE-like activitya | amiE gene detectionb | AmiF-like activitya | amiF gene detectionb | ||

| H. pylori N6 | 9.98 ± 1.98 | 2.32 ± 1.28 | + | 0.76 ± 0.62 | + |

| H. pylori 26695 | 3.17 ± 1.82 | 0.52 ± 0.35 | + | 2.7 ± 1.02 | + |

| H. acinonychis | 14.92 ± 1.59 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | + | 4.97 ± 3.52 | + |

| H. felis | 13.91 ± 1.59 | <0.01 | − | 8.19 ± 4.36 | + |

| H. mustelae | 42.46 ± 11.67 | <0.01 | − | 0.07 ± 0.02c | − |

| H. pametensis | <0.01 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

| H. cinaedi | <0.01 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

| H. bilis | 4.79 ± 2.07 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

| H. canis | <0.01 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

| H. muridarum | 1.11 ± 0.93 | 0.36 ± 0.17 | + | 0.04 ± 0.03c | − |

| H. hepaticus | 20.68 ± 7.79 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

| H. fennelliae | <0.01 | <0.01 | − | <0.01 | − |

Results are expressed as micromoles of substrate hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein ± standard deviation. The values shown are for the results of at least three independent experiments. The substrates used were urea for urease, acrylamide and acetamide for AmiE, and formamide for AmiF.

Detection was by Southern blot analysis with an amiE or amiF probe, as appropriate, except with H. hepaticus, for which genomic sequence data were available.

This value is close to the limit of detection of formamidase activity.

To further investigate the distribution of the amidases in the Helicobacter genus, we measured enzymatic activities on crude extracts for these Helicobacter species and for the two H. pylori strains (N6 and 26695) used as controls. For every strain, three different enzymatic activities were tested by measuring the ammonia produced in the presence of (i) urea for urease activity, (ii) formamide for AmiF-like formamidase activity, and (iii) acrylamide and acetamide for AmiE-like amidase activity (Table 3). As previously reported (45), urease activity was detected for all species except H. pametensis, H. cinaedi, H. canis, and H. fennelliae. Strong formamidase activity was detected for H. acinonychis and H. felis, whereas weak formamidase activity was detected for H. mustelae and activity close to the limit of detection was found for H. muridarum. Low formamidase activities could result from urease cross-reactivity on formamide, as shown previously with an H. pylori amiF mutant (42). This finding is in contrast with that for AmiE activity, which was below the limit of detection (<0.01 U) in an H. pylori amiE mutant.

Amidase activities with acrylamide and acetamide were found for H. acinonychis and H. muridarum in addition to the two H. pylori strains. H. muridarum was the only enterohepatic strain to display AmiE-like amidase activity. This unexpected result was confirmed by the measurement of the same AmiE-like amidase activities in three other H. muridarum isolates (ST2, -3, and -5) (Table 1). In addition, when positive, the AmiE amidase activity was always detected with both acrylamide and acetamide, suggesting a significant conservation of this enzyme.

DISCUSSION

H. pylori presents the original characteristic of possessing two amidases belonging to the aliphatic amidase family even though these enzymes are usually found only in bacteria from the environment. The hydrolysis of short-chain amides by the amidases provides the cell with ammonia. Ammonia is a central compound in H. pylori, as it is a major nitrogen source, contributes to the exceptional capacity of this organism to resist gastric acidity, and has a cytotoxic potential. We previously characterized the general aliphatic amidase, AmiE, and the AmiF formamidase (42, 43) of H. pylori and identified their in vitro substrates. The amidases are part of the nitrogen metabolic pathway of H. pylori; however, the origin of their natural substrates and the nature of the in vivo AmiE substrate remain unknown. We showed that the expression of the two amidases is dependent on the activity of two enzymes, urease and arginase, known to play a key role in nitrogen metabolism and colonization by this organism (42, 43). We proposed the existence of a common transcriptional regulatory network designed to maintain the intracellular nitrogen balance, to avoid toxic intracellular accumulation of ammonium, and possibly to respond to acid stress (9, 42). As H. pylori, with its unique gastric habitat, is still the only nonenvironmental bacteria to possess these enzymes, we hypothesized that these functions might have been selected through evolution because they confer a certain advantage to this bacterium for the colonization of its particular niche. Our in vivo competition experiments with the mouse did not detect a selective advantage for the strains possessing the amidases, but the mouse model might be badly suited to testing for subtle metabolic selective advantages. The potential influence of the amidase-produced ammonium on the degree of local gastric inflammation of mice still remains to be investigated.

Surprisingly, in our coinfection experiments, we observed that most of the mice were colonized with a single population corresponding to either of the two inoculated strains. Our interpretation is that only a very small subpopulation of the inoculated bacteria is able to colonize the mouse stomach, resulting in a clonality of in vivo infection by H. pylori. This is consistent with previous data (6) showing that 1 day after inoculation with the wild-type SS1 strain, the bacterial load of infected mice is below the detection limit; this clonality might be related to the presence of a mucus barrier. As a consequence, the results of coinfection experiments should be interpreted with caution. Testing the role of amidases in another animal model, such as the gerbil, which has a lower stomach pH than the mouse (48), might provide additional information on the role of these enzymes in colonization.

We then wanted to investigate the possibility that amidases might play a nonessential metabolic role in the colonization capacities of H. pylori. More and more metabolic functions are being found to be associated with pathogenicity, even though they are not essential virulence factors. These findings are illustrated by the fact that some of the horizontally acquired pathogenicity islands code for metabolic functions such as sucrose uptake in Salmonella senftenberg or catechol degradation in Pseudomonas putida (23). To approach this question, we decided to analyze the distribution of the amidase genes and activities in Helicobacter species with various colonization tropisms (gastric, hepatic, or enteric) and to examine whether there is a link between the colonization site and the presence of active amidases.

First, we examined the presence of the amiE and amiF genes in H. pylori strains from different geographic origins. Due to the plasticity of the H. pylori genome, the presence of these nonessential genes in every strain tested is highly significant and indicates that the amidase and formamidase play important metabolic functions, both of which have been maintained together during the evolution of H. pylori.

We sought the presence of amiE-like and amiF-like genes and amidase activities (general amidase and formamidase) in 11 Helicobacter species (Table 1) homogeneously distributed in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4). The Helicobacter genus contains more than 20 characterized species that can be classified as either gastric or enterohepatic (separated by a hatched line in Fig. 4). Examples of gastric Helicobacter species are H. pylori, H. felis, H. acinonychis, and H. mustelae, which colonize the stomachs of humans, cats, cheetahs, and ferrets, respectively. The tropism of the enterohepatic Helicobacter species is more diverse, and these species have been identified in the intestinal tracts and/or the livers of humans, other mammals, and birds (45).

In our analysis, there was a good correlation between the detection of amidase or formamidase activities and the presence of the corresponding genes. Among the four gastric strains tested, we observed that H. pylori and a closely related species, H. acinonychis, possessed both the AmiE amidase and the AmiF formamidase (Table 3). H. felis possessed only an AmiF-like formamidase. H. mustelae was devoid of both AmiE and AmiF activities and the corresponding genes. Very weak formamidase activity was measured, possibly due to a side activity of another enzyme such as urease, which is highly active in this organism. Interestingly, although H. mustelae is a ferret gastric pathogen, it is phylogenetically closer to the enterohepatic species than to the gastric species (45). H. muridarum was the only enterohepatic species tested found to display general amidase activity and to possess the corresponding amiE gene. This unexpected result is particularly interesting, given that H. muridarum is the only enterohepatic Helicobacter species known to colonize the mouse stomach in addition to its primary site in the intestine (45). In some cases, inflammatory lesions such as gastritis were found to be associated with stomach colonization by H. muridarum in mice (31).

These results indicate that amidases are found only in Helicobacter strains that are able to colonize the stomach, although they cannot be considered to be a specific marker for gastric Helicobacter. This type of association is what is expected from a metabolic function; having an amidase might enhance fitness in a particular environment and thus help a pathogen become more successful. However, having an amidase is not essential for the colonization of this niche, as suggested by our in vivo experiments and by the absence of amidase in H. mustelae. Amidases are not found in urease-negative Helicobacter species, supporting the notion that the activities of urease, amidase, and formamidase are coordinated.

To further investigate the link between the distribution of the amidases among the Helicobacter species and the tropism of these strains, we performed a phylogenetic analysis of these unusual enzymes to get insight into their origin and evolutionary history. The degree of identity between AmiE from H. pylori and its homologs from phylogenetically distant organisms is abnormally high: 74% for the homolog from P. aeruginosa and 74.3 and 76% for those from R. erythropolis and G. stearothermophilus, respectively (42, 43). The same observation is true for AmiF, for which two highly conserved homologs were recently found in the unfinished genomic sequences of two environmental bacteria, B. anthracis (75.5% identity) and D. vulgaris (74% identity). These high identity levels are particularly striking in comparison to the homologies between H. pylori housekeeping proteins and their homologs. For example, the MutY and GlmM proteins share 32 and 40% identity with their respective homologs from P. aeruginosa. Phylogenetic analyses indicated that the strongest evolutionary affinities of H. pylori amiE and amiF were with genes from low-G+C-content, gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 3). The discrepancy between the close relationship between the amidase genes from H. pylori and Bacillus spp. and the large evolutionary distance between the corresponding genomes is strongly suggestive of lateral gene transfer. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that the H. pylori amidase genes have atypical features in their own genomic context. The overall GC content of H. pylori is 39%, whereas the GC contents of amiE and amiF are 45 and 46.6%, respectively. These arguments, in agreement with the criteria developed by Lawrence and Ochman (30), give clues to the origin and direction of the lateral gene transfer. Ancestors of H. pylori probably acquired the amiE and amiF genes from the low-G+C-content, gram-positive bacterial lineage. Our phylogenetic data and the percentage of identity between each AmiE protein and each AmiF protein, around 34% whatever the organism, make it hard to distinguish between (i) functional convergence of these two enzymes and (ii) enzymes acquired by lateral gene transfer of two deep or hidden paralogs generated by very ancient gene duplication (maybe in a gram-positive organism). We favor this last, more complex hypothesis, although hidden paralogs are, by definition, difficult to identify (8).

When considering the presence of active amidases within the Helicobacter phylogenetic tree (Fig. 4), we observed that amiE and amiF are not systematically found together and are not uniformly distributed. The most likely evolutionary scenario is therefore the acquisition of alien amidase genes by different transfer events after the speciation of Helicobacter (Fig. 4). As both amiE and amiF are present together in two closely related species, H. pylori and H. acinonychis, gene transfer events could have first occurred in this phylogenetic branch. The minimal evolutionary scheme implies that an additional lateral gene transfer event took place, accounting for the presence of an amiE gene in H. muridarum. This model is supported by the absence of amidases in the closely related species H. hepaticus. At least two hypotheses can be formulated: (i) that the H. muridarum amiE gene was acquired from a non-Helicobacter organism and, because of this new function, it became able to colonize the stomach of mice more efficiently and (ii) that H. muridarum acquired an amiE gene by DNA exchange with a amidase-carrying gastric Helicobacter encountered during an episode of stomach colonization.

In conclusion, our distribution approach and phylogenetic analysis revealed original properties of the Helicobacter amidase genes. Aliphatic amidases are found only in Helicobacter species able to colonize the stomach. In addition, the amidase genes of H. pylori were obtained by horizontal transfer, possibly from a low-G+C-content, gram-positive organism. We hypothesize that the acquisition of these amidase genes might give the strain a metabolic advantage when colonizing an unusual ecological niche such as the stomach. It is noteworthy that H. pylori has the particularity of possessing an arginase, an enzyme-producing urea with a metabolic link to the amidases, for which the closest homolog is from Bacillus subtilis (34). It might not be a coincidence that B. subtilis is a low-G+C-content, gram-positive organism like the postulated donor organism of the amidases. Finally, we believe that using this type of genomic distribution approach to study the role of metabolic proteins will provide new insights into the natural history and adaptive potential of recently discovered pathogens such as H. pylori.

Acknowledgments

We thank Didier Mazel for the gift of pUC1813apra and Marie Moya for helpful discussions. We thank Jim G. Fox for the gift of the ATCC 51449 H. hepaticus strain and Sebastian Suerbaum for the unpublished information concerning the absence of the amidase genes in the H. hepaticus genome. We thank the CIP (Collection of the Pasteur Institute) for providing us with Helicobacter species. We also thank Ivo Boneca for critical reading of the manuscript and Richard Ferrero for stimulating discussions and for the gift of H. muridarum strains ST2, -3, and -5.

The work of D. E. Berg and D. Dailidiene was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI38166 and DK53727.

Editor: V. J. DiRita

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., and S. Suerbaum. 2000. Sequence variation in Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 8:57-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm, R. A., L. S. L. Ling, D. T. Moir, et al. 1999. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 397:176-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brau, B., U. Pilz, and W. Piepersberg. 1984. Genes for gentamicin-(3)-N-acetyltransferases III and IV. I. Nucleotide sequences of the AAC(3)-IV gene and possible involvement of an IS140 element in its expression. Mol. Gen. Genet. 193:179-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bury-Moné, S., S. Skouloubris, A. Labigne, and H. De Reuse. 2001. The Helicobacter pylori UreI protein: role in adaptation to acidity and identification of residues essential for its activity and for acid activation. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1021-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casadaban, M., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusions and cloning in E. coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chevalier, C., J.-M. Thiberge, R. L. Ferrero, and A. Labigne. 1999. Essential role of Helicobacter pylori γ-glutamyltranspeptidase for the colonization of the gastric mucosa of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 31:1359-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clyne, M., A. Labigne, and B. Drumm. 1995. Helicobacter pylori requires an acidic environment to survive in the presence of urea. Infect. Immun. 63:1669-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daubin, V., M. Gouy, and G. Perriere. 2002. A phylogenomic approach to bacterial phylogeny: evidence of a core of genes sharing a common history. Genome Res. 12:1080-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Reuse, H., and S. Skouloubris. 2001. Nitrogen metabolism, p. 125-133. In H. L. T. Mobley, G. L. Mendz, and S. L. Hazell (ed.), Helicobacter pylori: physiology and genetics. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [PubMed]

- 10.Dewhirst, F., C. Seymour, G. J. Fraser, B. J. Paster, and J. G. Fox. 1994. Phylogeny of Helicobacter isolates from bird and swine feces and description of Helicobacter pametensis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44:553-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn, B. E., H. Cohen, and M. Blaser. 1997. Helicobacter pylori. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:720-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eaton, K. A., F. E. Dewhirst, M. J. Radin, J. G. Fox, B. J. Paster, S. Krakowka, and D. R. Morgan. 1993. Helicobacter acinonyx sp. nov., isolated from cheetahs with gastritis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaton, K. A., and S. Krakowka. 1994. Effect of gastric pH on urease-dependent colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 62:3604-3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst, P. B., and B. D. Gold. 2000. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: the immunopathogenesis of gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:615-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsenstein, J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrero, R. L., V. Cussac, P. Courcoux, and A. Labigne. 1992. Construction of isogenic urease-negative mutants of Helicobacter pylori by allelic exchange. J. Bacteriol. 174:4212-4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrero, R. L., J.-M. Thiberge, M. Huerre, and A. Labigne. 1998. Immune responses of specific-pathogen-free mice to chronic Helicobacter pylori (strain SS1) infection. Infect. Immun. 66:1349-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox, J. G., F. E. Dewhirst, J. G. Tully, B. J. Paster, L. Yan, N. S. Taylor, M. J. J. Collins, P. L. Gorelick, and J. M. Ward. 1994. Helicobacter hepaticus sp. nov., a microaerophilic bacterium isolated from livers and intestinal mucosal scrapings from mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1238-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox, J. G., N. S. Taylor, P. Edmonds, and D. J. Brenner. 1988. Campylobacter pylori subsp. mustelae subsp. nov. isolated from the gastric mucosa of ferrets (Mustela putorius furo), and an emended description of Campylobacter pylori. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 38:367-370. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox, J. G., L. L. Yan, F. E. Dewhirst, B. J. Paster, B. Shames, J. C. Murphy, A. Hayward, J. C. Belcher, and E. N. Mendes. 1995. Helicobacter bilis sp. nov., a novel Helicobacter species isolated from bile, livers, and intestines of aged, inbred mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:445-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gascuel, O. 1997. BIONJ: an improved version of the NJ algorithm based on a simple model of sequence data. Mol. Biol. Evol. 14:685-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas, G., G. Karaali, K. Ebermayer, W. G. Metzger, S. Lamer, U. Zimny-Arndt, S. Diescher, U. B. Goebel, K. Vogt, A. B. Roznowski, B. J. Wiedenmann, T. F. Meyer, T. Aebischer, and P. R. Jungblut. 2002. Immunoproteomics of Helicobacter pylori infection and relation to gastric disease. Proteomics 2:313-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hentschel, U., and J. Hacker. 2001. Pathogenicity islands: the tip of the iceberg. Microbes Infect. 3:545-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins, D. G. 1994. Clustal V: multiple alignment of DNA and protein sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 25:307-318. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Igarashi, M., Y. Kitada, H. Yoshiyama, A. Takagi, T. Miwa, and Y. Koga. 2001. Ammonia as an accelerator of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis of gastric epithelial cells in Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect. Immun. 69:816-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janvier, B., B. Grignon, C. Audibert, L. Pezennec, and J. L. Fauchère. 1999. Phenotypic changes of Helicobacter pylori components during an experimental infection in mice. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 24:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleanthous, H., G. A. Myers, K. M. Georgakopoulos, T. J. Tibbitts, J. W. Ingrassia, H. L. Gray, R. Ding, Z.-Z. Zhang, W. Lei, R. Nichols, C. K. Lee, T. H. Ermak, and T. P. Monath. 1998. Rectal and intranasal immunizations with recombinant urease induce distinct local and serum immune responses in mice and protect against Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect. Immun. 66:2879-2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Labigne, A., V. Cussac, and P. Courcoux. 1991. Shuttle cloning and nucleotide sequence of Helicobacter pylori genes responsible for urease activity. J. Bacteriol. 173:1920-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lalioui, L., and C. Le Bouguénec. 2001. afa-8 gene cluster is carried by a pathogenicity island inserted into the tRNAPhe of human and bovine pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Infect. Immun. 69:937-948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawrence, J. G., and H. Ochman. 2002. Reconciling the many faces of lateral gene transfer. Trends Microbiol. 10:1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, A., M. Chen, N. Coltro, J. O'Rourke, S. Hazell, P. Hu, and Y. Li. 1993. Long term colonization of the gastric mucosa with Helicobacter species does induce atrophic gastritis in an animal model of Helicobacter pylori infection. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 280:38-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, A., J. O'Rourke, M. Corazon De Ungria, B. Robertson, G. Daskalopoulos, and M. F. Dixon. 1997. A standardized mouse model of Helicobacter pylori infection: introducing the Sydney strain. Gastroenterology 112:1386-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, A., M. W. Phillips, J. L. O'Rourke, B. J. Paster, F. E. Dewhirst, G. J. Fraser, J. G. Fox, L. I. Sly, P. J. Romaniuk, and T. J. Trust. 1992. Helicobacter muridarum sp. nov., a microaerophilic helical bacterium with a novel ultrastructure isolated from the intestinal mucosa of rodents. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendz, G. L., E. M. Holmes, and R. L. Ferrero. 1998. In situ characterization of Helicobacter pylori arginase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1388:465-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Mobley, H. L. T., G. L. Mendz, and S. L. Hazell (ed.). 2001. Helicobacter pylori: physiology and genetics. ASM Press, Washington, D.C. [PubMed]

- 37.Paster, B. J., A. Lee, J. G. Fox, F. E. Dewhirst, L. A. Tordoff, G. J. Fraser, J. L. O'Rourke, N. S. Taylor, and R. Ferrero. 1991. Phylogeny of Helicobacter felis sp. nov., Helicobacter mustelae, and related bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Posada, D., and K. A. Crandall. 2001. Selecting models of nucleotide substitution: an application to human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1). Mol. Biol. Evol. 18:897-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez, F., J. F. Oliver, A. Marin, and J. R. Medina. 1990. The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitutions. J. Theor. Biol. 142:485-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salama, N. R., G. Otto, L. Tompkins, and S. Falkow. 2001. Vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori plays a role during colonization in a mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 69:730-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 42.Skouloubris, S., A. Labigne, and H. De Reuse. 2001. The AmiE aliphatic amidase and AmiF formamidase of Helicobacter pylori: natural evolution of two enzyme paralogs. Mol. Microbiol. 40:596-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skouloubris, S., A. Labigne, and H. De Reuse. 1997. Identification and characterization of an aliphatic amidase in Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Microbiol. 25:989-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skouloubris, S., J.-M. Thiberge, A. Labigne, and H. De Reuse. 1998. The Helicobacter pylori UreI protein is not involved in urease activity but is essential for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect. Immun. 66:4517-4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solnick, J. V., and D. B. Schauer. 2001. Emergence of diverse Helicobacter species in the pathogenesis of gastric and enterohepatic diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:59-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanley, J., D. Linton, A. P. Burnens, F. E. Dewhirst, R. J. Owens, A. Porter, S. L. W. On, and M. Costas. 1993. Helicobacter canis sp. nov., a new species from dogs: an integrated study of phenotype and genotype. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:2495-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.Suerbaum, S., C. Josenhans, T. Sterzenbach, B. Drescher, P. Brandt, M. Bell, M. Dorge, B. Fartmann, H. P. Fischer, Z. Ge, A. Horster, R. Holland, K. Klein, J. Konig, L. Macko, G. L. Mendz, G. Nyakatura, D. B. Schauer, Z. Shen, J. Weber, M. Frosch, and J. G. Fox. 2003. The complete genome sequence of the carcinogenic bacterium Helicobacter hepaticus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7901-7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Swofford, D. K. 1998. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (and other methods), 4 ed. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.

- 48.Takashima, M., T. Furuta, H. Hanai, H. Sugimura, E. Kaneko. 2001. Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric acid secretion and serum gastrin levels in Mongolian gerbils. Gut 48:765-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomb, J.-F., O. White, A. R. Kerlavage, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 388:539-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Totten, P. A., C. L. Fennell, F. C. Tenover, J. M. Wezenberg, P. L. Perine, W. E. Stamm, and K. K. Holmes. 1985. Campylobacter cinaedi (sp. nov.) and Campylobacter fennelliae (sp. nov.): two new Campylobacter species associated with enteric disease in homosexual men. J. Infect. Dis. 151:131-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsujii, M., S. Kawano, T. Tsuji, K. Ito, Y. Sasaki, N. Hayashi, H. Fusamoto, and T. Kamada. 1993. Cell kinetics of mucosal atrophy in rat stomach induced by long-term administration of ammonia. Gastroenterology 104:796-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandamme, P., E. Falsen, R. Rossau, B. Hoste, P. Segers, R. Tytgat, and J. de Ley. 1991. Revision of Campylobacter, Helicobacter, and Wolinella taxonomy: emendation of generic descriptions and proposal of Arcobacter gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41:88-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]