Abstract

The present study addressed the ability of moxifloxacin to penetrate into healthy and inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissues in 12 patients with soft tissue infections (STIs). Penetration of moxifloxacin into the interstitial space fluid of healthy and inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissues was measured by use of in vivo microdialysis following administration of a single intravenous dosage of 400 mg in six diabetic and six nondiabetic patients with STIs. For the entire study population, the mean time-concentration profile of free moxifloxacin in plasma was identical to the time-concentration profile of free moxifloxacin in tissue (P was not significant). For healthy and inflamed adipose tissues for the diabetic subgroup, the mean moxifloxacin areas under the concentration-time curves (AUCs) from 0 to 8 h (AUC0-8s) were 8.1 ± 7.1 and 3.7 ± 1.9 mg·h/liter, respectively (P was not significant). The ratios of the mean AUC0-8 for inflamed tissue/AUC0-8 for free moxifloxacin in plasma were 0.5 ± 0.4 for diabetic patients and 1.2 ± 0.8 for nondiabetic patients (P was not significant). The ratios of the AUCs from 0 to 24 h for free moxifloxacin in plasma/MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited were >58 and 121 h for Streptococcus species and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. Concentrations of moxifloxacin effective against clinically relevant bacterial strains are reached in plasma and in inflamed and healthy adipose tissues. Thus, the pharmacokinetics of moxifloxacin in tissue and plasma support its use for the treatment of STIs in diabetic and nondiabetic patients.

Antibiotic therapy of soft tissue infections (STIs) must be directed against the most prevalent and virulent pathogens and therefore requires effective antimicrobial coverage. However, in some cases initial antibiotic therapy fails to be effective (9, 26), which can be attributed to inappropriate initial drug selection, impaired drug tissue penetration properties, or the development of bacterial resistance to the administered antibiotic agent.

Moxifloxacin, a relatively new 8-methoxyfluoroquinolone antibiotic, acts not only against gram-negative bacteria and intracellular and atypical organisms but also against gram-positive pathogens (19, 32). Plasma moxifloxacin concentrations were shown to exceed the MICs for periods sufficient to eradicate many clinically relevant bacteria (23). Optimal bacterial killing by moxifloxacin can be expected at the site of infection if the time-concentration profiles of moxifloxacin in inflamed lesions equal or exceed the time-concentration courses in plasma. However, recent studies have demonstrated that rapid or complete equilibration of antibiotics between plasma and tissue cannot be taken for granted for each clinical setting and patient population (4, 16), particularly for those patients who suffer from substantially impaired local or systemic blood flow (6, 17).

Hence, the present study was carried out to determine the penetration characteristics of moxifloxacin in patients with STIs. In a subgroup analysis, we gathered information on moxifloxacin penetration into tissue in diabetic patients and compared the time-concentration profiles for healthy and inflamed adipose tissues in diabetic patients who had angiopathy with those for tissues in nondiabetic controls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study took place at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Vienna Medical School, Vienna, Austria. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) in the revised version of 1996 (Somerset West), the Guidelines of the International Conference of Harmonization, the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Austrian drug law. All patients were given a detailed description of the study, and their written consent was obtained prior to the enrollment in the study.

Patients.

Twelve Caucasian patients (five women and seven men) with severe STIs of the lower limbs requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy were included. Patients received moxifloxacin for study purposes only. Each patient underwent a screening examination, comprising a medical history and a physical examination. Women of childbearing potential were required to have undergone pregnancy tests that yielded negative results.

Measurement of interstitial space moxifloxacin concentrations.

In vivo microdialysis was used for the measurement of free interstitial space moxifloxacin concentrations (20, 22). This method is based on sampling of analytes from the interstitial space by means of a semipermeable membrane at the tip of a microdialysis probe. The probe was constantly perfused with a physiological solution at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min. Once the microdialysis probe is implanted into tissues, substances present in the interstitial space fluid at a certain concentration (Ctissue) diffuse out of the extravascular fluid into the probe, resulting in a concentration in the perfusion medium (Cdialysate). For most analytes, equilibrium between Ctissue and Cdialysate is incomplete; therefore, Ctissue is >Cdialysate. The factor by which the concentrations are interrelated is termed “relative recovery.”

For calibration of the microdialysis probes, in vivo recovery was assessed in each experiment by the retrodialysis method (22). The principle of this method is based on the fact that the process of diffusion through the semipermeable membrane is equal in both directions. Therefore, moxifloxacin was added to the perfusion medium, and the disappearance rate (delivery) through the membrane was subsequently calculated.

The in vivo percent recovery value was calculated as 100 − [100 · (Cdialysate/Cperfusate)], where Cperfusate is the concentration in the perfusate. In vivo recovery was assessed for each experiment by dialyzing the tissue (healthy or inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissue) with a perfusion medium containing 0.5 mg of moxifloxacin per liter for 30 min.

Measurement of moxifloxacin concentrations.

For the measurement of moxifloxacin concentrations in plasma and microdialysates, a reversed-phase chromatography method with a high-performance liquid chromatograph column with fluorescence detection was used according to a validated method published by Stass et al. (28). Cinoxacin was used as the internal standard. The levels of precision ranged from 1.55 to 4.14% for plasma and from 3.05 to 10.0% for microdialysates.

Study protocol.

Blood and microdialysate samples were collected at defined time points or time intervals ranging from 15 min to 2 h. Microdialysis experiments were performed as described previously (20, 22). In brief, two commercially available microdialysis probes (CMA 10; Microdialysis AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with cutoffs of 20 kDa, outer diameters of 0.5 mm, and membrane lengths of 16 mm were inserted into subcutaneous adipose tissues of the thigh. One microdialysis probe was inserted into the inflamed lesion, and the reference probe was inserted into healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue of the contralateral thigh by the following procedure: the surface of the skin was punctured with a 20-gauge intravenous plastic cannula. The steel needle was removed, the appropriate positioning of the probe was checked by aspiration, and the dialysis probe was inserted into the plastic cannula. The microdialysis system was connected to a precision pump (Precidor; Infors-AG, Basel, Switzerland) and perfused with Ringer's solution at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min. After a 30-min baseline sampling period, 400 mg of moxifloxacin (Moxifloxacin 400 mg Infusionsflasche; Bayer, Wuppertal, Germany) was administered to the patients with an automatic infusion apparatus (Infusionspumpe IP 85-2; Döring Medizintechnik, Leverkusen, Germany) over a period of 60 min. The infusion solution was protected from light. Sampling of microdialysates and plasma was continued at defined time intervals for up to 3 days postdosing. All samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Calculations for microdialysis experiments.

Each microdialysis probe was calibrated in vivo. The absolute concentrations in the interstitial space (in milligrams per liter) were calculated by the following formula: 100 · (Cdialysate/individual concentration recovered).

PK calculations.

The level of plasma protein binding of moxifloxacin was reported to range from about 50 to 70% (27). For the present study free moxifloxacin concentrations were calculated from total concentrations in plasma by using a given level of plasma protein binding of 50%. Pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis was performed with a computer program (Kinetica, version 3.0; Innaphase Sarl, Paris, France), and PK parameters were calculated by noncompartmental approaches. The area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for plasma and the interstitium were calculated from nonfitted data by using the linear trapezoidal rule. The volume of drug distribution at steady state (Vss) and clearance (CL) were calculated for plasma in patients by use of standard formulae, as follows: CL = dose/total AUC and Vss = CL × MRT, where MRT represents the mean residence time of a molecule. MRT was calculated by use of the formula MRT = AUMC/AUC, where AUMC is the area under the moment time-concentration curve.

The following main PK parameters were determined: AUC, maximum concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (Tmax), and the half-life for the terminal slope (t1/2β). The main PK data are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Main PK parameters calculated for the study populationa

| Population and compartment | AUC0-8 for tissue/ AUC0-8 for free plasma | AUC0-8 (mg · h/liter) | AUC0-24b (mg · h/liter) | Cmax (mg/liter) | Tmax (h) | t1/2β (h) | CL (liters/h) | Vss (liters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire population (n = 11) | ||||||||

| Plasma, total | 16.4 ± 5.5 | 29.5 ± 12.0 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 11.0 ± 3.1 | 13.0 ± 5.8 | 150 ± 42 | |

| Inflamed tissue | 0.9 ± 0.7 | 6.4 ± 4.1 | 9.7 ± 6.1 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 1.3 | NDc | ND |

| Healthy tissue | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 5.7 | 13.2 ± 16.4 | 1.2 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 6.3 ± 2.3 | ND | ND |

| Diabetic patients (n = 5) | ||||||||

| Plasma, total | 17.5 ± 5.4 | 33.6 ± 16.4 | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 13.0 ± 3.5 | 10.9 ± 6.0 | 146 ± 48 | |

| Inflamed tissue | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 6.0 ± 2.9 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 2.6 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | ND | ND |

| Healthy tissue | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 8.1 ± 7.1 | 20.8 ± 22.0 | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 2.2 | ND | ND |

| Nondiabetic patients (n = 6) | ||||||||

| Plasma, total | 15.4 ± 5.9 | 26.0 ± 10.6 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 8.6 ± 1.6 | 14.8 ± 5.6 | 152 ± 41 | |

| Inflamed tissue | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 8.7 ± 4.1 | 12.8 ± 6.4 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.3 | ND | ND |

| Healthy tissue | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 4.2 | 6.9 ± 7.1 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 1.7 | ND | ND |

Data are means ± SDs for 11 patients.

Data for AUC for tissue were calculated from time zero to infinity.

ND, not determined.

Statistical calculations.

Mann-Whitney U tests were performed for statistical comparison of PK parameters between diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Data within individuals were compared by use of paired Wilcoxon tests. All PK data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SDs). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patients.

Twelve patients were enrolled in the present study. The demographic data for the patients are presented in Table 1. The diabetic patients had had diabetes for a median duration of 13.5 years (range, 10 to 20 years). All diabetic patients had documented peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) of the lower limbs. Severe Fontaine stage IV PAOD of the lower limbs (31) was present in five diabetics, and stage IIb PAOD was diagnosed in one patient. PAOD without ulcer or gangrene was present in two nondiabetic patients. The median serum creatinine levels were not significantly different between the groups. All patients completed the study and were available for safety analysis.

TABLE 1.

Demographic dataa

| Parameters | Diabetics (n = 6) | Nondiabetics (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 65 (50-89) | 57 (23-80) |

| Wt (kg) | 74 (64-161) | 82 (39-90) |

| BMIb (kg/m2) | 24.8 (23.7-51.8) | 25.7 (17.3-33.1) |

| Leukocyte count (109/liter) | 8.3 (7.2-11.8) | 7.2 (4.3-13.4) |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 651 (360-711) | 446 (409-742) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.91 (0.69-1.01) | 0.99 (0.73-1.15) |

| Size of infected area (cm2) | 40 (20-100) | 40 (6-200) |

Value are medium (ranges).

BMI; body mass index.

Microdialysis experiments.

The malfunction of microdialysis probes rendered the moxifloxacin PK profile invalid for one patient from the diabetic group. Therefore, tissue data sets for 11 patients were eligible for PK analysis.

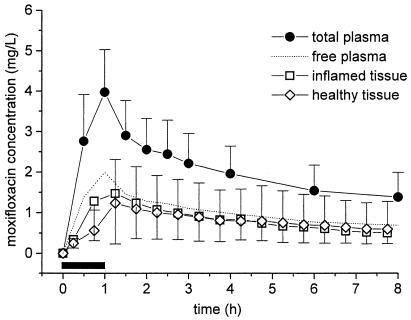

The results of in vivo microdialysis experiments show that the concentrations of moxifloxacin in the interstitial space are consistently lower than the total concentrations in plasma (Table 2; Fig. 1). For the entire study population, moxifloxacin concentrations in tissues (n = 11) closely resembled the time-concentration course of free moxifloxacin in plasma (n = 12) (Fig. 1). The ratios of the AUC from 0 to 8 h (AUC0-8) for tissue/AUC0-8 for free plasma ranged from 0.7 to 0.9 for inflamed and healthy tissues (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Time-concentration profiles of moxifloxacin for total plasma (n = 11), free plasma, inflamed tissue (n = 11), and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue (n = 11) after administration of a single intravenous dosage of 400 mg over 60 min to patients with STIs. The horizontal black bar indicates the duration of intravenous moxifloxacin administration. Data are shown as means ± SDs.

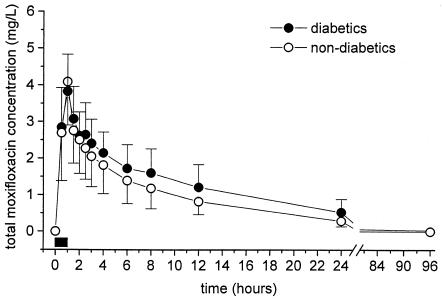

The time-concentration courses of total moxifloxacin in plasma were comparable between diabetics and nondiabetics (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Time-concentration profiles of total moxifloxacin in plasma for diabetic patients (n = 5) and nondiabetic patients (n = 6). The horizontal black bar indicates the duration of intravenous moxifloxacin administration. Data are shown as means ± SDs.

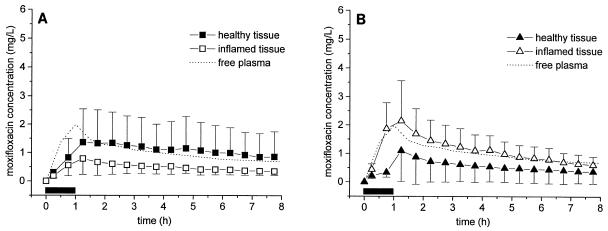

A statistical analysis of the diabetic and nondiabetic subgroups shows that moxifloxacin penetration into healthy, unaffected subcutaneous tissues was not significantly different between groups (Table 2). The moxifloxacin concentrations in the inflamed lesions of nondiabetics were descriptively higher than those in the inflamed lesions of diabetic patients (P was not significant) (Fig. 3). The ratios of the mean AUC0-8 for inflamed tissue/mean AUC0-8 for free plasma were 0.5 ± 0.4 and 1.2 ± 0.8 for diabetic and nondiabetic patients, respectively. The mean Cmaxs in inflamed adipose tissue lesions were 0.8 ± 0.5 and 2.3 ± 1.2 mg/liter for diabetic and nondiabetic patients, respectively. However, these differences in main PK parameters were not significantly different because of the relatively small sample size and the large interindividual variability of the moxifloxacin PKs in tissue (coefficients of variation, up to 130%).

FIG. 3.

(A) Time-concentration profiles of free moxifloxacin for free plasma, healthy adipose tissue, and inflamed tissue in diabetic patients (n = 5). (B) Time-concentration profiles of free moxifloxacin in plasma, healthy adipose tissue, and inflamed adipose lesions in nondiabetic patients. The horizontal black bar indicates the duration of intravenous moxifloxacin administration. Data are shown as means ± SDs.

The main PK parameters for moxifloxacin in plasma and the interstitia of inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissues are presented in Table 2.

Safety and tolerability.

Study drug administration was well tolerated by all patients. No significant prolongation of the QTc interval was observed. No study drug-related severe adverse events were observed within the follow-up period of 30 days.

DISCUSSION

Some worrisome recent reports have linked the development of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents either to their excessive and uncritical use (12, 14) or to the exposure of bacteria to ineffective antibiotic concentrations (10, 30). This is in line with the observation that subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents at the target site may promote the emergence of resistant bacteria (8, 13). Against this background we performed the present study to investigate the ability of moxifloxacin to penetrate the interstitia of healthy and inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissues by use of in vivo microdialysis. Although the present study was not designed for subgroup analysis, we also aimed to obtain a first insight into the impact of diabetic angiopathy disorder on moxifloxacin penetration into tissue and compared the time-concentration profiles for diabetic patients with those for nondiabetic patients.

A key finding of the present study is that for the entire study population the free moxifloxacin concentrations in the interstitia of healthy and inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissues resemble the time-concentration course of free moxifloxacin in plasma (Fig. 1). A subgroup analysis indicates that moxifloxacin equilibrates rapidly with the interstitia of healthy tissues and inflamed tissues in diabetic (Fig. 3A) and nondiabetic (Fig. 3B) patients, respectively. In diabetic patients, the concentrations of moxifloxacin in inflamed tissues are descriptively lower than those in healthy adipose tissues, although the limited number of patients and the high degree of interindividual variability do not allow statistical confirmation of this trend. Thus, the data from the present study generate the hypothesis that penetration into inflamed subcutaneous lesions is restricted in diabetic patients.

A potential explanation for the descriptively lower concentrations of moxifloxacin in inflamed tissues in diabetics might be that long-term diabetic patients (mean duration, 10 years for our study population) suffer from a poor vascular supply in the lower limbs because of angiopathy of the micro- and macrovessels. Insufficient blood flow in tissues triggers the development of ulcers or gangrene. Nevertheless, in diabetic patients ulcerated regions tend to be warmer and more edematous than healthy adipose tissues, regardless of the presence of infection (1). In the present study, microdialysis probes were implanted very close to the margins of the ulcers in all diabetic patients. In contrast, nondiabetic patients had tissue infections without ischemic or necrotic regions, and the microdialysis probes were positioned in inflammatory, well-perfused, hyperemic zones. It is expected that local inflammation itself causes an increase in capillary permeability, contributing to enhanced rates of exchange of moxifloxacin between plasma and tissue. However, local edema combined with impaired arterial blood flow at the inflammatory site may completely reverse this effect to such a magnitude that the concentrations of moxifloxacin in the inflammatory tissue of diabetic patients equal the concentrations in unaffected tissues in nondiabetic patients. Thus, our data on lower Cmax and AUC values in inflamed subcutaneous lesions in diabetic patients fit the concept that blood flow is a very important determinant for drug exchange between compartments, as recently suggested by several clinical studies with ciprofloxacin (17), β-lactams (16, 18), imipenem (29), and other small diffusible molecules (6).

In recent years increasing attention has been paid to the membrane P glycoprotein (P-gp), an ATP-dependent unspecific efflux pump. P-gp is expressed on the membrane in certain tissues, including the skin, particularly on capillary endothelial cells in venules (7), and is overexpressed or activated in inflammatory states (2). While activation of P-gp results in greater differences in drug concentrations between compartments, its inhibition facilitates equilibration of the concentration between compartments (5). Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that differences in the PKs of moxifloxacin in tissue are related to the modulation of P-gp activity (21). Moxifloxacin, however, was recently reported to be only a moderate substrate of efflux pump mechanisms, which is in contrast to the findings for other fluoroquinolones (24).

Our finding of descriptively incomplete equilibration of moxifloxacin between plasma and tissue for inflamed lesions in diabetic patients might be of clinical relevance, because meeting of a specific threshold value for the AUC from 0 to 24 h (AUC0-24)/MIC is predictive of the clinical and bacteriological outcomes for fluoroquinolones (10, 11, 15, 25). In addition, failure to achieve this goal was reported to be associated with an increased likelihood for the development of resistance of gram-negative bacteria to fluoroquinolones (30).

By looking at the most common bacterial strains causing STIs, such as Streptococcus species (MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited, 0.25 mg/liter) (32) or methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MIC at which 90% of isolates are inhibited, 0.12 mg/liter) (32), and given a mean AUC0-24 for free plasma of approximately 14.5 mg·h/liter (Table 2), AUC0-24 for free plasma/MIC ratios will range between 58 and 121 h after administration of a single intravenous dose of 400 mg of moxifloxacin. Corresponding Cmaxs are very close to the mutant prevention concentration (MPC), i.e., the concentration at which bacterial mutations are expected to occur rarely during fluoroquinolone therapy (3, 33). However, the MPC is an in vitro measurement that is determined with constant concentrations, and it is unknown for how long bacteria must be exposed in vivo to prevent the emergence of resistance. Thus, the clinical value of MPC needs to be verified in clinical settings.

In conclusion, the present study has shown that concentrations of moxifloxacin effective against clinically relevant bacterial strains, including methicillin-sensitive S. aureus and Streptococcus species, are attained in plasma and the interstitia of healthy and inflamed subcutaneous lesions. Thus, the PKs of moxifloxacin in plasma and tissue indicate that moxifloxacin qualifies for the management of STIs in diabetic and nondiabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our study nurse, Petra Zeleny, for essential contributions to the study.

This work was supported by a research grant from Bayer Corporation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong, D. G., L. A. Lavery, P. J. Liswood, W. F. Todd, and J. A. Tredwell. 1997. Infrared dermal thermometry for the high-risk diabetic foot. Phys. Ther. 77:169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertilsson, P. M., P. Olsson, and K. E. Magnusson. 2001. Cytokines influence mRNA expression of cytochrome P450 3A4 and MDRI in intestinal cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 90:638-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondeau, J. M., X. Zhao, G. Hansen, and K. Drlica. 2001. Mutant prevention concentrations of fluoroquinolones for clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:433-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunner, M., T. Pernerstorfer, B. X. Mayer, H. G. Eichler, and M. Müller. 2000. Surgery and intensive care procedures affect the target site distribution of piperacillin. Crit. Care Med. 28:1754-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, Y. L., M. H. Chou, M. F. Lin, C. F. Chen, and T. H. Tsai. 2001. Effect of cyclosporine, a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, on the pharmacokinetics of cefepime in rat blood and brain: a microdialysis study. Life Sci. 69:191-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clough, G. F., P. Boutsiouki, M. K. Church, and C. C. Michel. 2002. Effects of blood flow on the in vivo recovery of a small diffusible molecule by microdialysis in human skin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302:681-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordon-Cardo, C., J. P. O'Brien, J. Boccia, D. Casals, J. R. Bertino, and M. R. Melamed. 1990. Expression of the multidrug resistance gene product (P-glycoprotein) in human normal and tumor tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 38:1277-1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagan, R., K. P. Klugman, W. A. Craig, and F. Baquero. 2001. Evidence to support the rationale that bacterial eradication in respiratory tract infection is an important aim of antimicrobial therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:129-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, R., A. Markham, and J. A. Balfour. 1996. Ciprofloxacin. An updated review of its pharmacology, therapeutic efficacy and tolerability. Drugs 51:1019-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firsov, A. A., I. Y. Lubenko, S. N. Vostrov, O. V. Kononenko, S. H. Zinner, and Y. A. Portnoy. 2000. Comparative pharmacodynamics of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin in an in vitro dynamic model: prediction of the equivalent AUC/MIC breakpoints and equiefficient doses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:725-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest, A., D. E. Nix, C. H. Ballow, T. F. Goss, M. C. Birmingham, and J. J. Schentag. 1993. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1073-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales, R., D. C. Malone, J. H. Maselli, and M. A. Sande. 2001. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould, I. M., and F. M. MacKenzie. 2002. Antibiotic exposure as a risk factor for emergence of resistance: the influence of concentration. Symp. Ser. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 31:78S-84S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huovinen, P. 2002. Macrolide-resistant group A streptococcus—now in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 346:1243-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyatt, J. M., P. S. McKinnon, G. S. Zimmer, and J. J. Schentag. 1995. The importance of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic surrogate markers to outcome. Focus on antibacterial agents. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 28:143-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joukhadar, C., M. Frossard, B. X. Mayer, M. Brunner, N. Klein, P. Siostrzonek, H. G. Eichler, and M. Müller. 2001. Impaired target site penetration of beta-lactams may account for therapeutic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit. Care Med. 29:385-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joukhadar, C., N. Klein, M. Frossard, E. Minar, H. Stass, E. Lackner, M. Herrmann, E. Riedmüller, and M. Müller. 2001. Angioplasty increases target site concentrations of ciprofloxacin in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 70:532-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joukhadar, C., N. Klein, B. X. Mayer, N. Kreischitz, G. Delle-Karth, P. Palkovits, G. Heinz, and M. Müller. 2002. Plasma and tissue pharmacokinetics of cefpirome in patients with sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 30:1478-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krasemann, C., J. Meyer, and G. Tillotson. 2001. Evaluation of the clinical microbiology profile of moxifloxacin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32(Suppl. 1):S51-S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lönnroth, P., P. A. Jansson, and U. Smith. 1987. A microdialysis method allowing characterization of intercellular water space in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 253:E228-E231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer, U., E. Wagenaar, B. Dorobek, J. H. Beijnen, P. Borst, and A. H. Schinkel. 1997. Full blockade of intestinal P-glycoprotein and extensive inhibition of blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein by oral treatment of mice with PSC833. J. Clin. Investig. 100:2430-2436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller, M., O. Haag, T. Burgdorff, A. Georgopoulos, W. Weninger, B. Jansen, G. Stanek, H. Pehamberger, E. Agneter, and H. G. Eichler. 1996. Characterization of peripheral-compartment kinetics of antibiotics by in vivo microdialysis in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2703-2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller, M., H. Stass, M. Brunner, J. G. Moller, E. Lackner, and H. G. Eichler. 1999. Penetration of moxifloxacin into peripheral compartments in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2345-2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raherison, S., P. Gonzalez, H. Renaudin, A. Charron, C. Bebear, and C. M. Bebear. 2002. Evidence of active efflux in resistance to ciprofloxacin and to ethidium bromide by Mycoplasma hominis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:672-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schentag, J. J., D. E. Nix, and M. H. Adelman. 1991. Mathematical examination of dual individualization principles. I. Relationships between AUC above MIC and area under the inhibitory curve for cefmenoxime, ciprofloxacin, and tobramycin. DICP Ann. Pharmacother. 25:1050-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seppala, H., T. Klaukka, J. Vuopio-Varkila, A. Muotiala, H. Helenius, K. Lager, P. Huovinen et al. 1997. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:441-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siefert, H. M., A. Domdey-Bette, K. Henninger, F. Hucke, C. Kohlsdorfer, and H. H. Stass. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of the 8-methoxyquinolone, moxifloxacin: a comparison in humans and other mammalian species. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43(Suppl. B):69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stass, H., and A. Dalhoff. 1997. Determination of BAY 12-8039, a new 8-methoxyquinolone, in human body fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection using on-column focusing. J. Chromatogr. B Biomed. Sci. Appl. 702:163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tegeder, I., A. Schmidtko, L. Brautigam, A. Kirschbaum, G. Geisslinger, and J. Lotsch. 2002. Tissue distribution of imipenem in critically ill patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 71:325-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas, J. K., A. Forrest, S. M. Bhavnani, J. M. Hyatt, A. Cheng, C. H. Ballow, and J. J. Schentag. 1998. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of factors associated with the development of bacterial resistance in acutely ill patients during therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:521-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner, F. W., Jr. 1981. The dysvascular foot: a system for diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle 2:64-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodcock, J. M., J. M. Andrews, F. J. Boswell, N. P. Brenwald, and R. Wise. 1997. In vitro activity of BAY 12-8039, a new fluoroquinolone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:101-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao, X., and K. Drlica. 2001. Restricting the selection of antibiotic-resistant mutants: a general strategy derived from fluoroquinolone studies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33(Suppl. 3):S147-S156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]