Abstract

The aim of the present study was to characterize the population pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in patients with and without cystic fibrosis ranging in age from 1 day to 24 years and to propose a limited sampling strategy to estimate individual pharmacokinetic parameters. Patients were divided into four groups according to the treatment schedule. They received ciprofloxacin by intravenous infusion (30 min) or by the oral route. The number of samples collected from each patient ranged from 1 to 12. The population parameters were computed for an initial group of 37 patients. The data were analyzed by nonlinear mixed-effect modeling by use of a two-compartment structural model. The interindividual variability in clearance (CL) was partially explained by a dependence on age and the patient's clinical status. In addition, a significant relationship was found between weight and the initial volume of distribution. Eighteen additional patients were used for model validation and evaluation of limited sampling strategies. When ciprofloxacin was administered intravenously, sampling at a single point (12 h after the start of infusion) allowed the precise and accurate estimation of CL and the elimination half-life, as well as the ciprofloxacin concentration at the end of the infusion. It should be noted that to take into account the presence of a lag time after oral administration, a schedule based on two sampling times of 1 and 12 h is needed. The results of this study combine relationships between ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters and patient covariates that may be useful for dose adjustment and a convenient sampling procedure that can be used for further studies.

Hospitalized pediatric patients with serious infections are a challenge to the clinician who takes care of them. Indeed, the pharmacokinetics of most drugs are age dependent (4, 8, 32). Maturation of metabolic pathways takes place at different rates; the level of metabolic clearance of drugs is very low at birth and then increases to reach a maximum at about age 1 year, when it can exceed that for adults. Renal blood flow, the glomerular filtration rate, and tubular secretion are all lower at birth and then increase to approach the values for adults by the end of the first year of life. There are also significant changes in drug disposition and in the quantity and quality of plasma proteins in the first few years of life. Moreover, pharmacokinetics can be modified according to the pathological status of the patient. It is well known that pathological changes that occur in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) can lead to alterations in the dispositions of many drugs (26). However, the information available on the dispositions of most antibacterial agents commonly used to treat hospitalized pediatric patients is scarce.

Fluoroquinolones have a broad spectrum of in vitro antimicrobial activity against a variety of pathogens. These drugs are occasionally used to treat pediatric patients with severe infections for which no other treatment is possible, especially per os. Potential indications in pediatrics are CF-related infections, salmonellosis, and shigellosis due to resistant strains; severe neonatal infections due to members of the family Enterobacteriaceae; complicated urinary tract infections; and severe infections due to resistant strains in immunocompromised patients (13, 31).

Among the fluoroquinolones, ciprofloxacin has been shown to have excellent concentration-dependent activity—and thereby, excellent activity against the infection—against nosocomial infections caused by multiresistant bacteria that occurred in neonatal intensive care units and against a variety of microorganisms found in bronchial sputum from patients with CF (14, 18, 34, 36). Two bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are usually the first pathogens encountered in children with CF (10). Until recently, ciprofloxacin was not widely used in the pediatric age group (17) because of the potential occurrence of weight-bearing joint arthropathy, as has been observed in animals exposed to ciprofloxacin and other halogenated quinolones (6). However, on the basis of past experience showing satisfactory safety, its use in children is now allowed in selected situations (2, 24, 40). Today, ciprofloxacin is not yet licensed for administration to children younger than 5 years of age, and a dosage regimen has not been established. However, in early 2003 this drug was licensed in France for administration to children under age 5, but not patients with CF, for the treatment of severe infections.

Ciprofloxacin nonrenal clearance mechanisms are important, accounting for approximately one-third of its elimination. Glomerular filtration and tubular secretion account for about 66% of the total clearance (CL) in adults (37).

Only a few pharmacokinetic studies have reported data on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in pediatric patients with CF (20, 27, 28, 33) and in patients without CF (22, 38). The number of patients included in all of those studies was small. Most of the studies have been carried out with patients older than 5 years of age. Only Peltola et al. (22) determined the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in infants without CF aged 5 to 14 weeks. Those investigators reported that ciprofloxacin appeared to be eliminated markedly more slowly in the postnatal group than in the group aged 1 to 5 years. Moreover, patients with CF have an increased volume of distribution and enhanced CL of ciprofloxacin compared with those for subjects who do not have CF (27). Dose adjustment by Bayesian forecasting, which results in improvements in the rates at which therapeutic drug concentrations are achieved and in patient clinical outcomes (39), could play an important role in the optimization of drug dosage regimens for this vulnerable population of patients with large interpatient variability. However, population studies of the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin have been performed only with adults (5, 12, 19, 35), and no data are available for the pediatric population. The most widely used methods for population modeling were nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM) and nonparametric expectation maximization (NPEM2) (5, 19, 35).

The present study was carried out to provide data on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in order to optimize care for pediatric patients. It was performed with 53 pediatric patients ages 1 day to 17 years and 2 young adults (ages 20 and 24 years). The first objective of this work was to determine accurate population pharmacokinetic parameters for ciprofloxacin in a population of patients covering a wide age range by using a two-compartment open model. This model takes into account the dependence of body weight, age, and the patient's clinical status (CF or no CF) on pharmacokinetic parameters. A NONMEM approach (with NONMEM software) was used to estimate population pharmacokinetic parameters. To verify the predictive performance of this method, subsequent ciprofloxacin concentrations were predicted in a study with an independent group of patients and then compared to the measured concentrations. The secondary objective of the study was to propose a limited sampling strategy for estimation of CL, the elimination half-life (t1/2β), and ciprofloxacin concentrations after both intravenous and oral administrations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Fifty-five patients with or without CF ranging in age from 1 day to 24 years were included in this study. They were admitted to the Gastroenterology or Nephrology Unit, the Department of Neonatology, or the Department of Pediatric Surgery of Robert Debré Hospital (Paris, France). The demographic characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1; age classification was performed according to the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) harmonized tripartite guideline (16). CF patients (20 patients ranging in age from 4 to 24 years) were eligible to participate in this trial if they had an acute exacerbation of infection with P. aeruginosa. The other 35 patients (ages, 1 day to 13 years) had infections caused by multiresistant organisms. The diagnosis of infection was based on both clinical and bacteriological evaluations.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Age category | No. of patients | No. of patients with CF | Mean age (yr)a | Mean wt (kg)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn infants | 3 | 0 | 0.004 (0.003-0.006) | 2.12 (1.37-3.5) |

| Infants and toddlers | 17 | 0 | 0.50 (0.083-1) | 5.5 (0.75-9.2) |

| Children | 27 | 13 | 5.6 (2-11) | 18.6 (8-33) |

| Adolescents and young adults | 8 | 7 | 16.4 (12-24) | 42.3 (29-58) |

The values in parentheses are minimums-maximums.

For all patients, anamnestic data, a physical examination, and standard laboratory tests which included hematological and biochemical tests were performed before, during, and at the end of the study.

Concurrent use of antacids and vitamins containing divalent cations, H2 blockers, sucralfate, ketoconazole, and theophylline was not permitted during this study.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. It was performed in accordance with the legal requirements and the Declaration of Helsinki and with present European Community and U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidelines for good clinical practice. For pediatric patients, written consent was obtained from the patients and/or their parents (or legal guardians). The two patients older than age 18 years gave written consent.

Diagnostic criteria.

In CF patients, infection with P. aeruginosa was confirmed by bacteriological tests of the sputum.

Urinary tract infections (15 children) were defined as frequency, dysuria, or pyuria accompanied by a clean-voided urine specimen that yielded >105 CFU of a single organism per ml. The strains isolated were P. aeruginosa, group D streptococci, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas pickettii, and Enterococcus faecalis. Fever along with a toxic appearance, including tachypnea, tachycardia, and altered mental status in the presence of one or more positive blood cultures (the strains isolated were Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas cepacia, Serratia, and E. coli) obtained from percutaneous punctures of peripheral veins, supported a diagnosis of septicemia (three children). A gastrointestinal disorder was diagnosed in one child after isolation of Salmonella spp. from the fecal flora. Three children suffered from meningitis (the strain isolated was E. coli). Four children developed nosocomial pneumonia (the strains isolated were Serratia, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Mycoplasma hominis, and Ureaplasma), defined by its occurrence at least 4 days following admission to the intensive care unit, elevated temperature (>38.5°C), leukocytosis (>10 × 109 cells liter−1), purulent sputum at least 3 days before the trial, and lung infiltration on chest X ray. One of them died. Postsurgery infections were observed in seven patients (the strains isolated were Clostridium butyricum and Klebsiella spp.).

Treatment and sample collection.

The patients were divided into four groups according to the treatment schedule. The first group included 20 CF patients (age range, 4 to 24 years). They received an infusion of 10 mg of ciprofloxacin per kg of body weight over 30 min, followed by the administration of oral ciprofloxacin (15 mg/kg) every 12 h. The pharmacokinetic behavior of ciprofloxacin was assessed on day 1 of treatment (i.e., after the infusion and administration of the first oral dose). Blood samples were obtained at the following times: (i) immediately before intravenous administration; (ii) at the end of the infusion; (iii) 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 h after the start of the infusion; and (iv) 1, 2, 4, 6, 10, and 12 h after administration of the first oral dose. The second group included 12 patients (age range, 2 days to 8 years) who received repeated intravenous infusions of ciprofloxacin (5 to 17 mg/kg, according to the patient) over 30 min. Two to three blood samples were drawn from each patient on the first day of treatment (the first one between 0.5 and 2 h, the second one between 4 and 6 h, and the third one between 10 and 12 h). The third group included 15 patients (age range, 1 to 13 years) who received repeated oral administrations of ciprofloxacin (7.5 to 30 mg/kg, according to the patient). One to three blood samples were collected from each patient, as reported above. The fourth group included eight pediatric patients (age range, 1 day to 4 years) who received repeated intravenous infusions of ciprofloxacin (8 to 15 mg/kg) over 30 min. One to two blood samples were drawn on the last day of treatment.

Blood samples were collected by means of an indwelling catheter in the arm opposite that used for infusion, placed in heparinized tubes, rapidly centrifuged, and then frozen at −20°C until assay.

For the CF patients, pancreatic enzymes, desoxycholic acid, and tocopherol acetate were also administered as part of long-term continuous therapy. Most of the patients without CF received concomitant antibiotic therapy (cefotaxime, netilmicin, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, amikacin, teicoplanin, ceftazidime, or vancomycin) and acetaminophen. None of these drugs are known to interact with ciprofloxacin.

Analytical method.

The drug analysis was undertaken at the Clinical Pharmacology Unit of Robert Debré Hospital. The ciprofloxacin concentration in plasma was assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography with spectrofluorometric detection. The detection was performed at 278 nm for excitation and 445 nm for emission. The assay was sensitive and specific. The concentration range of the quality control samples used during analysis was 70 to 700 μg/liter. Precision was in the range of 1.3 to 2.1%. Accuracy ranged from 1.3 to 2.1%. The limit of quantitation was 15 μg/liter. Analyses of unknown samples were performed within 15 days after sample collection.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis.

The subjects included were randomly allocated into a model-building set (population group; n = 37 patients [14 patients from group 1, 8 patients from group 2, 10 patients from group 3, and 5 patients from group 4]) and a test data set (validation group; n = 18 patients [6 patients from group 1, 4 patients from group 2, 5 patients from group 3, and 3 patients from group 4]). Potential explanatory covariables such as patient age, weight, gender, and clinical status were included in the original data files.

Pharmacostatistical model.

Pharmacokinetic analyses were performed by using the NONMEM approach as implemented in the NONMEM computer program (version 5.1) (3) through the Visual-NM graphical interface (25). The population characteristics for the pharmacokinetic parameters (fixed and random effects) were estimated by using the subroutines ADVAN-4 and TRANS-1 from the library of programs provided with the NONMEM-PREDPP package. Both first-order and first-order conditional estimation methods were used to estimate population pharmacokinetic parameters. The estimation was markedly improved by use of the first-order method.

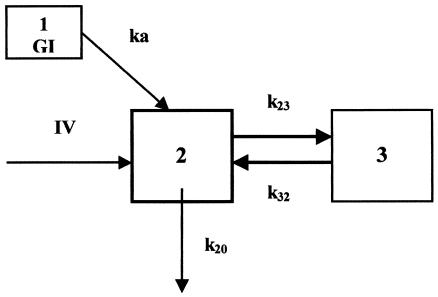

By using the data for the subjects with an extensive sampling schedule, preliminary analyses (data not shown) were conducted to select the structural model. Two- and three-compartment models with a zero- or first-order input rate from the gastrointestinal tract were compared. Model discrimination was performed by using Akaike's information criterion, the log likelihood function, and the residuals distribution. The two-compartment model with a first-order input rate after oral administration (Fig. 1) best described the data and was therefore chosen as the most appropriate model for the population analysis. Then, a NONMEM run performed with the model-building data set (including rich and sparse data) without covariates was carried out to choose the pharmacostatistical model (data not shown). The seven-dimensional vector θ of kinetic parameters considered in the population analysis consisted of CL, transfer rate constants (k23 and k32), absorption rate constant (ka), initial volume of distribution (V), bioavailability (F), and lag time.

FIG. 1.

Two-compartment model used to fit ciprofloxacin data. GI, gastrointestinal tract; IV, zero-order intravenous infusion rate; 2, central compartment; 3, peripheral compartment; ka, first-order input rate; k23 and k32, intercompartmental rate constants; k20, first-order elimination.

Interindividual variability was assessed by use of a proportional error model associated with each fixed-effect parameter; thus, for example, CL for subject j (CLj) was described by the relationship

|

(1) |

where CLmean is the mean CL for the population, and ηCL is the difference between the population CLmean and the CL for subject j; ηCL is assumed to be a Gaussian random variable with mean of zero and variance σ2η. The error on the concentration measurements for individual j [Cijk(t)] was modeled by use of a proportional model, described as follows:

|

(2) |

where pj is the pharmacokinetic parameters of individual j; tij is the time of the ith measurement; Dij is the dosing history of subject j; f is the pharmacokinetic model; and ɛij represents the residual departure of the model from the observations and contains contributions from intraindividual variability, assay error, and model misspecification for the dependent variable. ɛij is assumed to be a random Gaussian variable with a mean of zero and variance σ2.

The individual predicted concentrations (IPREDs) in plasma were computed for each individual by using the empirical Bayes estimate of the pharmacokinetic parameters by using the POSTHOC option in the NONMEM program.

Estimation of population parameters.

Data analysis was performed by using a three-step approach. (i) In step 1, the population parameters (i.e., fixed and random effects) together with the individual posterior estimates were computed by assuming that no dependency existed between the pharmacokinetic parameters and the covariates. (ii) In step 2, following selection of the basic structural and statistical models, the influences of covariates were first assessed by plotting the individual empirical estimates obtained by the Bayesian methodology against all preselected potential covariates, namely, the gender, age, weight, and clinical status of the patient. When a relationship was detected, selected covariates were individually added to the model and tested for statistical significance. The change in the NONMEM objective function produced by the inclusion of a covariate term (asymptotically distributed as χ2, with the number of degrees of freedom equal to the number of parameters added to the model) was used to compare alternative models. A change in objective function of at least 3.8 (P < 0.05 with 1 degree of freedom) was required for statistical significance at the initial covariate screening stage. Finally, accepted covariates were added to the model and the population pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated. To demonstrate that retained covariates contributed to an improvement of the fit of the population pharmacokinetic model, each covariate was deleted sequentially from the proposed final model (backward elimination) in order to confirm statistical significance (by the χ2 test). If the objective function did not vary significantly, the relationship between the covariate and the pharmacokinetic parameter was ignored. (iii) In step 3, only the covariates providing a significant change in the objective function when they were introduced into the model were retained in the analysis. The population pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated by consideration of the relationship with the covariates.

Several secondary pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated from the individual primary pharmacokinetic parameters (estimated by the Bayesian methodology) t1/2β and the volume of distribution at the end of the distributive phase (Vβ). t1/2β was calculated as follows:

|

(3) |

where kel is the elimination rate constant, which is equal to CL/V. Vβ is equal to CL/β, where β is calculated as 0.693/t1/2β.

Model acceptance.

The adequacy of the model to the data was judged by using graphics and descriptive statistics. IPREDs were plotted versus observed concentrations (DVs), and the results were compared to the reference line with a slope of 1 and an intercept of 0. Residuals (IPRED − DV) were plotted versus time and versus IPRED. Descriptive statistics were used to compare mean residual values to 0 and to calculate 95% confidence intervals. The model was accepted when (i) the plots showed no systematic pattern and (ii) descriptive statistics did not show any systematic deviation from the initial hypothesis (the mean is supposed to be 0).

Performance of Bayesian individual parameter estimates.

Data for 18 patients (validation group) not included in the calculation of population parameters were used to evaluate the performance of the estimation by the Bayesian methodology. Individual pharmacokinetic parameters were computed by estimation by the Bayesian procedure by combining the prior knowledge of the mean and the dispersion of pharmacokinetic parameters in the population to which the selected individual belongs and the individual sample(s). From the resulting individualized parameter values, t1/2β, Vβ, and plasma ciprofloxacin concentrations at each sampling time (IPRED) were calculated for each patient.

Computing of a limited sampling strategy to estimate ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters.

Individual pharmacokinetic parameters (only CL and t1/2β were considered for this purpose, due to their clinical interest) were estimated on the basis of estimates obtained by the Bayesian methodology by using the NONMEM program with data for a limited number of samples. The database consisted of the data for the validation group of patients (six CF patients from group 1 with rich data). The rationale for the sampling strategy used was to select the concentrations in plasma that would be the most sensitive to differences in V (the peak concentration) and elimination (the peak and the subsequent trough concentrations) (1, 9, 11, 15). Moreover, it is very interesting for practical purposes to limit the number of samples to one. Thus, schedules with one (each of the six available samples) or two (10 combinations of samples) sampling times were tested.

Statistical analysis.

The performance of estimation by the Bayesian methodology was assessed for the validation group (18 patients) by comparing DVs to the concentrations estimated by the Bayesian approach (IPRED5) by using bias and precision (29, 30). (i) The bias or mean predictor error was calculated as follows:

|

(4) |

(ii) The precision or root mean square error was calculated as follows:

|

(5) |

In these equations for bias and precision, the index i refers to the number of concentrations, and N is the sample size. The 95% confidence interval for bias was computed, and the t test was used to compare the bias to 0.

To evaluate the reliability of the parameter estimates by using a limited sampling protocol, for each combination, CL, t1/2β, as well as ciprofloxacin concentrations estimated by the Bayesian methodology and a limited sampling strategy were compared to the values estimated by the Bayesian methodology and estimated with the entire set of data. These comparisons were performed by computing the bias and the precision.

RESULTS

Population pharmacokinetic parameters.

The pharmacokinetic parameter database consisted of 216 ciprofloxacin concentrations from 37 patients. In step 2, during covariate testing (i) the patient's age and clinical status were significantly related to CL and (ii) the patient's weight and clinical status were significantly related to V. In step 3 of the analysis, final population parameters were computed to account for the relationship between CL, age, and the patient's clinical status and between V and weight. The inclusion of this second-stage model significantly improved the fit of the basic model and provided a substantial decrease in unexplained interindividual variabilities in CL and V (from 435 to 103.4% and 128 to 73.1%, respectively). The objective function dropped from 3,230.3 to 2,848.8 (difference = 381.5; P < 0.001). The population pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Final population pharmacokinetic parameters for ciprofloxacina

| Population parameter | CL (liters/h)

|

V (liters)

|

k23 (h−1) (θ6) | k32 (h−1) (θ7) | ka (h−1) (θ8) | F (θ9) | Lag time (h) (θ10) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| θ4 | θ3 | θ5 | θ1 | θ2 | ||||||

| Population group (n = 37)b | ||||||||||

| Population mean | 1.93 | 0.469 | 16.7 | 2.17 | 0.908 | 0.340 | 0.429 | 0.423 | 0.852 | 0.798 |

| Interindividual variability (% CV) | 103.4 | 73.1 | 59.5 | 61.1 | 77.9 | 36.4 | 37.3 | |||

| All patients (n = 55)c | ||||||||||

| Population mean | 2.01 | 0.402 | 17.3 | 1.82 | 0.958 | 0.417 | 0.473 | 0.432 | 0.862 | 0.698 |

| Interindividual variability (% CV) | 96.5 | 76.9 | 24.1 | 50.6 | 102.5 | 32.1 | 54.8 | |||

CL = [θ3 + age · θ4] + θ5 · STAT (where STAT is the patient's clinical status); V = θ1 · weightθ2.

Intraindividual variability was 29.7%, and the objective function was 2,848.8.

Intraindividual variability was 34.3%, and the objective function was 4,197.3.

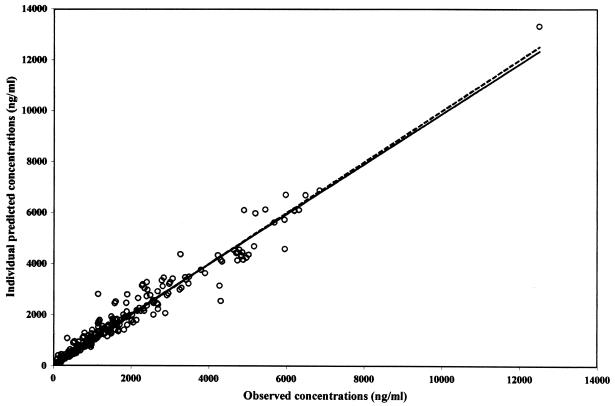

The goodness of fit has been evaluated (i) by comparing the regression line estimated with the individual predicted concentrations versus the observed concentrations (slope = 0.98, standard error of slope = 0.0116; intercept = 26.7 ng/ml, standard error of intercept = 33.4) to the reference line with a slope of 1 and an intercept of 0 (no significant difference occurred) (Fig. 2); (ii) by comparing the bias (−3.79 ng/ml with a 95% confidence interval of −60.9 to 53.3) to 0 (a t test showed that this value was not statistically different from 0); and (iii) by studying the frequency distribution histogram of the normalized residuals which reveals a distribution very close to the expected one (a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of unity).

FIG. 2.

Relationship between predicted (IPRED) and observed (DV) concentrations in plasma. The solid line represents the line of identity, and the dotted line represents the linear regression line.

Evaluation of Bayesian pharmacokinetic parameter prediction.

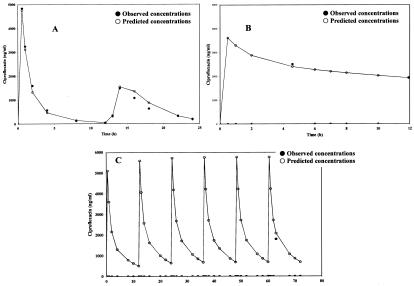

There was no statistically significant difference between the demographic data for the patients included in this evaluation and those for the population group. Individual pharmacokinetic parameters for the patients in the validation group (98 ciprofloxacin concentrations from 18 patients) were estimated by using the population characteristics. The results are given in Table 3. The regression line between the ciprofloxacin concentrations predicted by the empirical Bayes methodology and the individual observed ciprofloxacin concentrations did not differ significantly from the reference line with a slope of 1 and an intercept of 0. The bias (−35.8 ng/ml) was not statistically different from 0 (t test), and the 95% confidence interval included the 0 value (−63.0 to 21.4). Typical posterior individual fits are displayed in Fig. 3.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for patients in the validation groupa

| Parameter | Age (yr) | Wt (kg) | CL (liters/h) | t1/2ka (h) | Vβ (liters) | t1/2β (h) | F | Lag time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 0.005 | 1.37 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 3.26 | 2.15 | 0.67 | 0.40 |

| Maximum | 11.0 | 29.0 | 38.8 | 2.39 | 175 | 17.9 | 1.08 | 1.87 |

| Mean | 3.63 | 13.5 | 12.6 | 1.58 | 54.1 | 5.51 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| Interindividual variability (% CV) | 114 | 73.1 | 109 | 25.2 | 88.5 | 76.2 | 11.5 | 33.2 |

CV, coefficient of variation; t1/2ka, absorption half-life.

FIG. 3.

Typical posterior individual fits (validation group). (A) Patients in group 1 (age, 7 years); (B) patients in group 2 (age, 20 days); (C) patients in group 4 (age, 2 months).

Validation of limited sampling strategies.

Validation consisted of comparison of CL, t1/2β, and ciprofloxacin concentrations estimated by the Bayesian methodology with complete plasma concentration-time data (considered the reference values) to the ones determined by estimation by the Bayesian methodology and with limited sampling strategies. The results obtained with the better schedules (i.e., the schedules with one and two sampling times) are presented in Table 4. The precision was quite good for all strategies, and none of them was biased. However, the schedules with two sampling times (0.5 and 12 h or 1 and 12 h) and one sampling time (12 h) had better performances. For these three strategies, in comparison to the observed concentrations (5,224 ± 848 ng/ml), the maximum concentrations at the end of infusion were well estimated: 5,157 ± 751 ng/ml with sampling times of 0.5 and 12 h, 4,292 ± 437 ng/ml with sampling times of 1 and 12 h, and 4,799 ± 442 ng/ml with a sampling time of 12 h. Nevertheless, by using sampling schedules of 0.5 and 12 h or 12 h, the lag time after oral administration was poorly estimated and the predicted concentrations 1 and 2 h after drug intake were generally overestimated.

TABLE 4.

Predictive performance of Bayesian methodology for estimation of CL and t1/2β according to the different sampling strategies

| Sampling time (h) and parametera | CL (liters/h)

|

t1/2β (h)

|

Ciprofloxacin concn (ng/ml)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Bias | Precision | Mean | Bias | Precision | Mean | Bias | Precision | |

| All | |||||||||

| Mean | 30.4 | 2.35 | 1,179 | ||||||

| Min-max | 19-37 | 2.13-2.53 | 26-6,854 | ||||||

| % CV | 21.9 | 6.91 | 126 | ||||||

| 0.5-8 | |||||||||

| Mean | 27.4 | 2.97 (−1.55 to 7.5)b | 4.93 | 2.52 | −0.18 (−0.50 to 0.15) | 0.33 | 1,330 | −150 (−288 to 12.5) | 611 |

| Min-max | 16-33 | 2.17-3.09 | 40-5,153 | ||||||

| % CV | 21.8 | 12.8 | 104 | ||||||

| 0.5-12 | |||||||||

| Mean | 28.1 | 2.27 (−1.98 to 6.53) | 4.34 | 2.43 | −0.08 (−0.26 to 0.11) | 0.18 | 1,329 | −150 (−247 to 53) | 443 |

| Min-max | 16-34 | 2.17-2.70 | 14-6,633 | ||||||

| % CV | 23.0 | 9.28 | 113 | ||||||

| 1-12 | |||||||||

| Mean | 31.5 | −1.19 (−2.74 to 0.35) | 1.80 | 2.51 | −0.16 (−0.31 to 0.002) | 0.21 | 1,187 | −7.46 (−133 to 118) | 441 |

| Min-max | 20-38 | 2.26-2.84 | 14-5,524 | ||||||

| % CV | 21.5 | 9.85 | 109 | ||||||

| 8 | |||||||||

| Mean | 28.7 | 1.69 (−5.69 to 9.07) | 6.64 | 2.59 | −0.24 (−0.60 to 0.13) | 0.39 | 1,164 | 14.8 (−108 to 138) | 530 |

| Min-max | 24-34 | 2.11-3.18 | 22-4,695 | ||||||

| % CV | 15.9 | 14.3 | 109 | ||||||

| 12 | |||||||||

| Mean | 29.4 | 0.93 (−4.45 to 6.31) | 4.78 | 2.46 | −0.11 (−0.32 to 0.10) | 0.22 | 1,297 | 1.02 (−134 to 136) | 482 |

| Min-max | 24-35 | 2.15-2.71 | 15-5,129 | ||||||

| % CV | 15.5 | 10.1 | 110 | ||||||

Min-max, minimum-maximum; CV, coefficient of variation.

The values in parentheses represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Final population pharmacokinetic parameters.

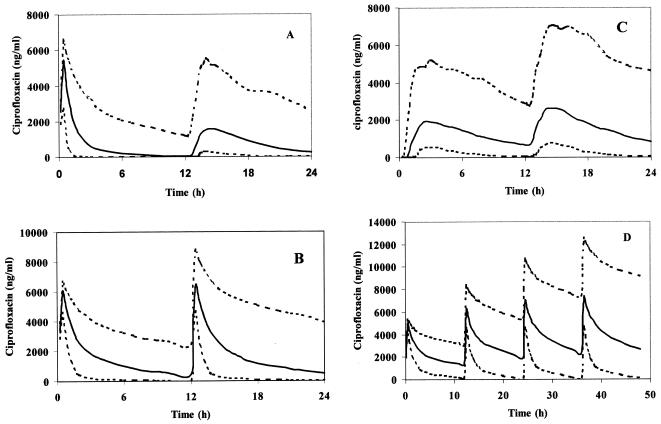

In the last step, population pharmacokinetic parameters were reestimated by using data for all individuals (314 ciprofloxacin concentrations from 55 patients). The results are given in Table 2. The CL from plasma was 14.8 ± 13.8 liters/h (range, 110 ml/h to 50.3 liters/h). Mean values for the secondary parameters calculated by estimation by the Bayesian methodology were t1/2β equal to 5.30 ± 4.30 h (range, 1.82 to 24.5 h) and Vβ equal to 67.1 ± 56.0 liters (range, 2.40 to 244 liters). Finally, simulations were accomplished by performing a Monte Carlo simulation (23) for a typical patient in each age group, including the 95% confidence intervals, plus the variability identified. Two hundred simulations were performed. The results are presented in Fig. 4.

FIG. 4.

Simulations for typical patients in each age group. (A) Group 1, mean age, 10.5 years; mean weight, 28.7 kg; intravenous dose, 330 mg; oral dose, 480 mg; (B) group 2, mean age, 2.6 years; mean weight, 9.9 kg; intravenous dose, 125 mg; (C) group 3, mean age, 4.6 years; mean weight, 17.2 kg; oral dose, 250 mg; (D) group 4, mean age, 0.13 years; mean weight, 3.75 kg; intravenous dose, 40 mg. The dotted lines represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Due to differences in the ages of the individuals in the population studied, mean pharmacokinetic parameters are presented, according to ICH harmonized tripartite guidelines (16), in Table 5. In the 2- to 11-year-old age group, CL from plasma was higher in CF patients (24.5 liters/h; coefficient of variation, 32.9%; n = 13) than in patients without CF (12.2 liters/h; coefficient of variation, 67.9%; n = 13).

TABLE 5.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters for study patients according to the age categories of the ICH harmonized tripartite guidelinesa

| Group (age) parameter | CL (liters/h) | t1/2β (h) | Vβ (liters) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn infants (0-28 days) (n = 3) | |||

| Minimum | 0.11 | 10.5 | 3.83 |

| Maximum | 0.82 | 24.5 | 12.4 |

| Mean | 0.39 | 16.6 | 7.19 |

| % CVb | 96.0 | 42.9 | 63.4 |

| Infants and toddlers (28 days-23 mo) (n = 17) | |||

| Minimum | 0.29 | 3.24 | 2.40 |

| Maximum | 8.79 | 12.8 | 41.1 |

| Mean | 2.93 | 6.16 | 20.9 |

| % CV | 85.7 | 37.9 | 55.3 |

| Children (2-11 yr) (n = 27) | |||

| Minimum | 0.58 | 1.82 | 16.6 |

| Maximum | 37.4 | 19.9 | 141 |

| Mean | 17.7 | 4.16 | 73.4 |

| % CV | 59.6 | 94.3 | 43.6 |

| Adolescents and young adults (12-24 yr) (n = 8) | |||

| Minimum | 21.7 | 2.40 | 103 |

| Maximum | 50.3 | 4.89 | 244 |

| Mean | 35.7 | 3.32 | 166 |

| % CV | 22.9 | 18.2 | 28.5 |

The ICH harmonized tripartite guidelines are presented elsewhere (16).

CV, coefficient of variation.

DISCUSSION

It is well known that the pharmacokinetics of most drugs are age dependent (4, 8, 32). Moreover, alterations in the absorption, disposition, and elimination (i.e., increases in both the volume of distribution and CL and a decrease in the rate of absorption) of many drugs have been reported in CF patients (19, 26); these alterations seem to be more pronounced as the severity of illness increases (27). However, there is a paucity of pharmacokinetic data for pediatric patients, particularly neonates, as most drug treatments and many empirical treatment practices are based on data for adults.

The present study was undertaken in light of the limited information that exists concerning the pharmacokinetic profile of ciprofloxacin in pediatric patients. At variance to previously reported data (22, 27, 28, 33, 38), the population enrolled in this study was affected by large variabilities in age (1 day to 24 years) and weight (0.75 to 58 kg). Patient classification was performed according to the ICH harmonized tripartite guidelines (16). Our objectives were (i) to determine accurate population pharmacokinetic parameters for ciprofloxacin by using a two-compartment open model and (ii) to propose a limited sampling strategy to estimate individual pharmacokinetic parameters and plasma ciprofloxacin concentrations.

Both, NONMEM and NPEM2 have been used for population pharmacokinetic modeling for pediatric patients, but to date, only a few studies have compared these methods for subjects in the same age group (7, 21). The study conducted by Patoux et al. (21) was carried out after carboplatin administration to children. The investigators concluded that there are no differences in bias or precision between the two methods. de Hoog et al. (7) showed that the NONMEM approach gave a significantly smaller bias after the administration of tobramycin to neonates, but there was no significant difference in precision. In the present study, population parameters after the administration of ciprofloxacin were estimated by using the NONMEM approach. This population modeling method described the data for ciprofloxacin well. Relationships between ciprofloxacin CL, age, and the patient's clinical status and between V and weight were taken into account in the final model. The performance of estimation by the Bayesian methodology was evaluated by using plasma concentration-time data for patients not included in the calculation of the population parameters. The low values of the bias and the precision for prediction of concentration (290 ng/ml, which is lower than the interindividual standard deviation of 1,483 ng/ml) showed that the population characteristics allowed a good prediction of the individual pharmacokinetic parameters in very different subjects with different pathologies (including CF patients) belonging to the same population. Indeed, in the group of patients with CF, CL ranged from 130 ml/h to 38.8 liters/h and t1/2β ranged from 2.15 to 17.9 h.

This study showed that ciprofloxacin was eliminated markedly more slowly from newborn infants than from the other children studied. Moreover, CL was about two times higher in patients with CF than in subjects who did not have CF. These findings are in accordance with data reported in the literature (22, 27). In each group of patients, large interindividual variability in pharmacokinetic parameters occurred.

For determination of ciprofloxacin CL and t1/2β in the clinical routine with minimal constraints for patients, we propose the use of a limited sampling strategy based on estimation by the Bayesian methodology with the NONMEM program. It is very interesting for practical purposes to limit the number of samples to one, especially for pediatric patients. Thus, schedules of sampling at one or two points were tested. When the ciprofloxacin treatment was administered solely by the intravenous route, sampling at a single point (12 h after the start of infusion) allowed the precise and accurate estimation of CL and t1/2β as well as the plasma ciprofloxacin concentration at the end of the infusion. It should be noted that to take into account the lag time that occurred after oral administration, a schedule based on two sampling times (1 and 12 h after drug intake) is needed.

In the last step, ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated for all patients (n = 55). The pharmacokinetic parameters computed for the population were of the same order of magnitude as those computed for the 37 patients.

In conclusion, the population approach developed in this study should allow monitoring of the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin on a large scale, especially to avoid underdosing of pediatric patients with serious infections. The limited sampling strategy proposed in this paper for estimation of individual ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters may be useful for optimization of care for pediatric patients. Moreover, the suggested convenient sampling procedure might be used in further studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Banna, M. K., A. W. Kelman, and B. Whitng. 1990. Experimental design and efficient parameter estimation in population pharmacokinetics. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 18:347-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alghasham, A. A., and M. C. Naahata. 2000. Clinical use of fluoroquinolones in children. Ann. Pharmacother. 34:347-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beal, S. L., and L. B. Sheiner. 1994. NONMEM user's guide. University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco.

- 4.Bouwmeester, N. J., J. N. Van Den Anker, W. C. Hop, K. J. Anand, and D. Tibboel. 2003. Age- and therapy-related effects on morphine requirements and plasma concentrations of morphine and its metabolites in postoperative infants. Br. J. Anaesth. 90:642-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breilh, D., M. C. Saux, P. Maire, J. M. Vergnaud, and R. W. Jelliffe. 2001. Mixed pharmacokinetic population study and diffusion model to describe ciprofloxacin lung concentrations. Comput. Biol. Med. 31:147-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkhardt, J. E., M. A. Hill, W. W. Carlton, and J. W. Kesterson. 1990. Histologic and histochemical changes in articular cartilages of immature beagle dogs dosed with difloxacin, a fluoroquinolone. Vet. Pathol. 27:162-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Hoog, M., R. C. Schoemaker, J. N. van den Anker, and A. Vinks. 2002. NONMEM and NPEM2 population modeling: a comparison using tobramycin data in neonates. Ther. Drug Monit. 24:359-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Hoog M., J. W. Mouton, and J. N. van den Anker. 2003. Thoughts on “Population pharmacokinetics and relationship between demographic and clinical variables and pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in neonates.” Ther. Drug. Monit. 25:256-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drusano, G. L. 1991. Optimal sampling theory and population modelling: application to determination of the influence of the microgravity environment on drug distribution and elimination. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 31:962-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerson, J., M. Rosenfeld, S. McNamara, B. Ramsey, and R. L. Gibson. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 34:91-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endrenyi, L. 1981. Design of experiments for estimating enzyme and pharmacokinetic experiments, p. 137-167. In L. Endrenyi (ed.), Kinetic data analysis, design and analysis of enzyme and pharmacokinetic experiments. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Forrest A., C. H. Ballow, D. E. Nix, M. C. Birmingham, and J. J. Schentag. 1993. Development of a population pharmacokinetic model and optimal sampling strategies for intravenous ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1065-1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gendrel, D., F. Moulin, H. Sauvé-Martin, and J. Raymond. 2001. Les fluoroquinolones en pédiatrie. Med. Mal. Infect. 31:105-114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoiby, N. 1982. Microbiology of lung infection disease in cystic fibrosis patients. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 301:33-54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurst, A. K., M. A. Yoshinaga, G. H. Mitani, K. A. F. Too, R. W. Jelliffe, and E. C. Harrison. 1990. Application of a Bayesian method to monitor and adjust vancomycin dosage regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1165-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guidelines. 2000. Clinical investigation of medicinal products in the pediatric population. [Online.] http://www.fda.gov/oc/gcp/draft.html [PubMed]

- 17.Kubin, R. 1993. Safety and efficacy of ciprofloxacin in paediatric patients—review. Infection 21:413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lesnes-Hulin, A., P. Bourget, F. Ravat, C. Goudin, and J. Latarjet. 1999. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in patients with major burns. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 55:515-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery M. J., P. M Beringer., A. Aminimanizani, S. G. Louie, B. J. Shapiro, R. Jelliffe, and M. A. Gill. 2001. Population pharmacokinetics and use of Monte Carlo simulation to evaluate currently recommended dosing regimens of ciprofloxacin in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3468-3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odoul, F., C. Le Guellec, C. Giraut, C. de Gialluly, S. Marchand, G. Paintaud, M. C. Saux, J. C. Rolland, and E. Autert-Leca. 2001. Ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics in young cystic fibrosis patients after repeated oral doses. Therapie 56:519-524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patoux, A., N. Bleyzac, A. V. Boddy, F. Doz, H. Rubie, G. Bastian, P. Maire, P. Canal, and E. Chatelut. 2001. Comparison of nonlinear mixed-effect and non-parametric expectation maximisation modelling for Bayesian estimation of carboplatin clearance in children. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peltola, H., M. Vaarala. O. V. Renkonen, and P. J. Neuvonen. 1992. Pharmacokinetics of single-oral dose ciprofloxacin in infants and small children. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:1086-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Press, W. H., B. P. Flannery, S. A. Teukolsky, and W. T. Vetterling. 1990. Numerical recipes, p. 498-546. In The art of scientific computing (Fortran version). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 24.Redmond, A., L. Sweeney, M. MacFarland, M. Mitchell, S. Daggett, and R. Kubin. 1998. Oral ciprofloxacin in the treatment of paediatric cystic fibrosis: clinical efficacy and safety evaluation using magnetic resonance image scanning. J. Int. Med. Res. 26:304-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Research Development in Population Pharmacokinetics. 1998. Visual-NM User's manual, version 5.1. RDPP, Montpellier, France.

- 26.Rey, E., J. M. Treluyer, and G. Pons. 1998. Drug disposition in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 35:313-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubio, T. T., M. V. Miles, J. T. Lettieri, R. J. Khun, R. M. Echols, and D. A. Church. 1997. Pharmacokinetic disposition of sequential intravenous/oral ciprofloxacin in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients with acute pulmonary exacerbation. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:112-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaefer, H. G., H. Stass, J. Wedgwood, B. Hampel, C. Fischer, J. Kuhlmann, and U. B. Schaad. 1996. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:29-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheiner, L. B., and S. L. Beal. 1981. Some suggestions for measuring predictive performance. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 9:503-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheiner, L. B., and S. L. Beal. 1981. Evaluation of methods for estimating population pharmacokinetic parameters. II. Biexponential model and experimental pharmacokinetic data. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 9:635-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shortliffe, L. M., and J. D. McCue. 2002. Urinary tract infection at the age extremes: pediatrics and geriatrics. Am. J. Med. 113(Suppl. 1A):55S-66S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh, J., J. Burr, D. Stringham, and A. Arrieta. 2001. Commonly used antibacterial and antifungal agents for hospitalized paediatric patients. Implications for therapy with an emphasis on clinical pharmacokinetics. Paediatr. Drugs 3:733-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, A. L., A. Weber, R. Pandler, J. Williams-Warren, M. L. Cohen, and B. Ramsey. 1997. Utilisation of salivary concentrations of ciprofloxacin in subjects with cystic fibrosis. Infection 25:106-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanley, B. F. 1993. Clinical management of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Lancet 341:1070-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terziivanov, D., I. Atanasova, and V. Dimitrova. 1998. Population pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in patients with liver impairments analyzed by NPEM2 algorithm—a retrospective study. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 36:376-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turnidge, J. 1999. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of fluoroquinolones. Drugs 58:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vance-Bryan, K., D. R. P. Guay, and J. C. Rotschafer. 1990. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 19:434-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van den Oever, H. L. A., F. G. A. Versteegh, E. A. P. M. Thewessen, J. N. Van Den Anker, J. W. Mouton, and H. J. Neijens. 1998. Ciprofloxacin in preterm neonates: case report and review of the literature. Eur. J. Pediatr. 157:843-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinks, A. A. 2002. The application of population pharmacokinetic modeling to individualized antibiotic therapy. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 19:313-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Warren, R. W. 1997. Rheumatologic aspects of pediatric cystic fibrosis patients treated with fluoroquinolones. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:118-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]