Abstract

Two clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci (VS) with different degrees of susceptibility to optochin (OPT), i.e., fully OPT-susceptible (Opts) VS strain 1162/99 (for which the MIC was equal to that for Streptococcus pneumoniae, 0.75 μg/ml) and intermediate Opts VS strain 1174/97 (MIC, 6 μg/ml) were studied. Besides being OPT susceptible, they showed characteristics typical of VS, such as bile insolubility; lack of reaction with pneumococcal capsular antibodies; and lack of hybridization with rRNA (AccuProbe)-, lytA-, and pnl-specific pneumococcal probes. However, these VS Opts strains and VS type strains hybridized with ant, a gene not present in S. pneumoniae. A detailed characterization of the genes encoding the 16S rRNA and SodA classified isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 as Streptococcus mitis. Analysis of the atpCAB region, which encodes the c, a, and b subunits of the F0F1 H+-ATPase, the target of optochin, revealed high degrees of similarity between S. mitis 1162/99 and S. pneumoniae in atpC, atpA, and the N terminus of atpB. Moreover, amino acid identity between S. mitis 1174/97 and S. pneumoniae was found in α helix 5 of the a subunit. The organization of the chromosomal region containing the atp operon of the two Opts VS and VS type strains was spr1284-atpC, with spr1284 being located 296 to 556 bp from atpC, whereas in S. pneumoniae this distance was longer than 68 kb. In addition, the gene order in S. pneumoniae was IS1239-74 bp-atpC. The results suggest that the full OPT susceptibility of S. mitis 1162/99 is due to the acquisition of atpC, atpA, and part of atpB from S. pneumoniae and that the intermediate OPT susceptibility of S. mitis 1174/97 correlates with the amino acid composition of its a subunit.

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) remains a major etiological agent of community-acquired pneumonia, meningitis, and acute otitis media (6). Four phenotypic characteristics are classically used in the diagnostic laboratory for the identification of the pneumococcus: colony morphology on blood agar plates, optochin (OPT) susceptibility, bile solubility, and immunological reaction with type-specific antisera (23). Although their colony morphologies can be very similar, the alpha-hemolytic oral streptococci (known as viridans group streptococci [VS]), notably, Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis, are classically OPT resistant (Optr) and bile insoluble (23).

Genetic and biochemical evidence supports that fact that the typical OPT susceptibility of the pneumococcus resides in the characteristics of the F0 complex of its F0F1 H+-ATPase, an enzyme that is essential for the viability of this organism (10). The primary roles of this enzyme are to create a proton gradient with the energy provided by ATP hydrolysis and to maintain the intracellular pH via proton extrusion (25), as in other related bacteria (18). However, in bacteria with a respiratory chain, the role of the F0F1 H+-ATPase is the synthesis of ATP from the proton gradient of the respiratory chain. Hydrolysis of ATP on the cytoplasmic F1 sector (formed by the α, β, δ, ξ, and γ subunits) drives proton transport through the F0 cytoplasmic membrane sector (formed by the a, b, and c subunits) by long-range conformational changes. Conformational changes in the F1 β subunits drive hydrolysis of ATP (1), which generates rotation of the attached γ and ξ subunits. This rotation, in turn, causes the rotation of an oligomeric ring of c subunits (33, 38) and the pumping of protons across the membrane through F0. The activity of the F0F1 ATPase of S. pneumoniae is pH inducible and is regulated at the level of transcription initiation (25).

Pneumococcal strains resistant to amino-alcohol antimalarial drugs such as OPT, quinine (QIN), and mefloquine (MFL) have point mutations that change amino acid residues located in one of the two transmembrane α helices of the c subunit or in one of the two last α helices of the a subunit (9, 24, 28, 31), suggesting that those α helices of the c and a subunits interact and that the mutated residues are important for the structure of the F0 complex and proton translocation. Although OPT was used at the beginning of the 20th century for the treatment of pneumococcal infections (26), its use nowadays is restricted to diagnostic purposes due to its high level of toxicity. However, new, less toxic MFL-related compounds that also target the F0 complex of the F0F1 ATPase (24) have been synthesized (22).

Although several OPT-resistant S. pneumoniae isolates have been reported (21, 27, 30, 31, 40), to the best of our knowledge, there is a single report of VS with an OPT-susceptible phenotype (5). In this work we describe the genetic characterization of two Opts VS clinical isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

OPT sensitivity tests were performed by placing 5-μg OPT disks (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems) onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Difco) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood streaked with the bacteria being tested. After overnight incubation at 37°C in a CO2 atmosphere, the inhibition zones around the disk were measured, and isolates with zone diameters ≥14 mm were considered sensitive. MICs were determined by the microdilution method with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with 2.5% lysed horse blood, as recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (29). The inoculum was prepared by suspension of several colonies from an overnight blood agar culture in Mueller-Hinton broth and adjustment of the turbidity to a 0.5 McFarland standard (ca. 108 CFU/ml). The suspension was further diluted to provide a final bacterial concentration of 104 CFU/ml in each well of the microdilution trays. The plates were covered with plastic tape and incubated in ambient atmosphere at 37°C for 20 to 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of drug that inhibited visible growth. S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303 and ATCC 49619, S. mitis NCTC 12261T, and S. oralis NCTC 11427T and ATCC 10557 were used for quality control. OPT and QIN were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) MFL (Ro 21-5998-000) was provided by Roche Laboratories (Basel, Switzerland).

PCR amplification and DNA sequence determination.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from laboratory strain S. pneumoniae R6, S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. oralis NCTC 11427T, and the clinical isolates as described previously (12). Gel electrophoresis of the PCR products was carried out in agarose gels as described previously (35). PCR amplifications were performed with 0.5 to 1 U of Thermus thermophilus thermostable DNA polymerase (Biotools), 0.1 μg of chromosomal DNA, 0.4 to 1 μM (each) synthetic oligonucleotide primers, and 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate in a final volume of 50 μl in the buffer recommended by the manufacturers. Amplification was achieved with an initial cycle of 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 25 to 30 cycles of 30 to 60 s of denaturation at 94°C, 90 s of annealing at 55°C, and 1 to 2 min of polymerase extension at 72°C, with a final 8-min extension at 72°C and slow cooling at 4°C. The oligonucleotides used in the PCR amplifications are described in Table 1. To amplify the atpC and atpA genes, two pairs of oligonucleotides were used: atp660 (28) and atpB56 or atpWO and atpB56 (24). Several internal oligonucleotides were synthesized for the sequencing of the atpCA regions of the various strains used. Oligonucleotides atpc18RSpn, atpc18RSmi, atpc18RSor, and UPatp3 were used for sequencing of the atpC upstream regions. We also used primers 16SDNAF1 and 16SDNAR1 to amplify the 16S rRNA genes and the same primers and the internal oligonucleotides 16SDNAF2 and 16SDNAR2 for sequencing. Primers SOD-UP and SOD-DOWN were used to amplify and sequence of the sodA gene (20). PCR products were purified by using MicroSpin S400 HR columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and both strands were sequenced with an Applied Biosystems Prism 377 DNA sequencer.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this work

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Nucleotide (amino acid) positionsb |

|---|---|---|

| atp660 | ggtcggaaTTCCAATAGCGGTTAAAAGTTG | −83 to −62 of atpC |

| antDOWN | TCATGAGTCTTCTCCTCTCGC | Complementary to 853 to 873 of ant (285ARGEDS290) |

| antUP | GCTGTCGCCATGTCTGGTTCACG | 76 to 98 of ant (26AVAMSGSR33) |

| atpA 107R | GCGGTTGGCGAACTCCACCAG | Complementary to 318 to 338 of atpA (107WWSSPTA113) |

| atpB56 | GACGGGCTTCTTCAGCTCTGTC | Complementary to 169 to 147 of atpB (50DRAEEAR56) |

| atpc18RSmi | CCAAGAGACACACCCATACAGGC | Complementary to 31 to 53 of atpC (11ACMGVSVG18)c |

| atpc18RSor | GCAAGAGATACACCCATACAGGC | Complementary to 31 to 53 of atpC (11ACMGVSVG18)d |

| atpc18RSpn | CCGACAGATACGCCCATACAGGC | Complementary to 31 to 53 of atpC (11ACMGVSVG18) |

| atpWO | gcgcatgcTTAAAGGAGAATTTGTTATGAA | −15 to 5 of atpC (1MN2) |

| pepti101 | GCAGTTATCGTATCTGACCCAGCC | 304 to 327 of spr1284 (102AVIVSDPA109) |

| pepti413R | CGAACCATGTCTCCTGATTGAACGGG | Complementary to 1213 to 1238 of spr1284 (405PVQSGDMVR413) |

| UPatp3 | tcggaagcttAGGAAAAGCGCTTAAGAACA | −651 to −631 of atpC |

| 16SDNAF1 | GAGTTGCGAACGGGTGAGT | 86 to 104 of 16S rRNA |

| 16SDNAF2 | GTGGCGAAAGCGGCTCTCTGG | 719 to 739 of 16S rRNA |

| 16SDNAR1 | AGCGATTCCGACTTCAT | Complementary to 1326 to 1342 of 16S rRNA |

| 16sDNAR2 | CCAGAGAGCCGCTTTCGCCAC | Complementary to 719 to 739 of 16S rRNA |

The 5′ ends of atp660, atpWO, and UPatp3 contained sequences that included EcoRI, SphI, and HindIII restriction sites, respectively, which are underlined. Lowercase letters indicate bases not present in the nucleotide sequence of S. pneumoniae R6.

The nucleotide and amino acid numbering refers to the numbering for the genes and proteins of the S. pneumoniae R6 sequence, with the first nucleotide or amino acid being at position 1.

The nucleotide and amino acid numbering refers to the numbering for the atpC gene and protein of S. mitis NCTC 12261T, with the first nucleotide or amino acid being at position 1.

The nucleotide and amino acid numbering refers to the numbering for the atpC gene and protein of S. oralis NCTC 11427T, with the first nucleotide or amino acid being at position 1.

Southern blotting identification of strains and determination of genetic structures of chromosomal regions upstream of atpC.

For detection of the rRNA genes, the Accuprobe S. pneumoniae Culture Identification test (Gen-Probe, San Diego, Calif.) was used according to the instructions of the manufacturer with four colonies from an overnight culture on 5% blood agar. lytA- and pnl-specific DNA probes were prepared as described previously (11). A 798-bp probe derived from S. pneumoniae 3870 (11), a strain with a recombinational origin that had acquired the ant gene (which encodes amino acid residue positions 26 to 290 of the 290-amino-acid-residue Ant protein) from a VS strain (3), was obtained by PCR amplification with oligonucleotides antUP and antDOWN. The 936-bp spr1284-specific probe was obtained by amplification of S. pneumoniae R6 with oligonucleotides pepti101 and pepti413R. The atpCA-specific probe was obtained by amplification of S. pneumoniae R6 with oligonucleotides atpWO and atpA107R. DNA inserts and PCR fragments were labeled with the Phototope-Star detection kit (New England Biolabs). Southern blotting and hybridization were done according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the atpCAB genes reported here have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AY172982 (VS isolate 1162/99), AY172983 (VS isolate 1174/97), AY172984 (S. mitis NCTC 12261), AY172985 (S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303), and AY172986 (S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619). The sodA fragments have been assigned GenBank accession numbers AY314979 and AY314980.

RESULTS

Isolation and identification of strains 1162/99 and 1174/97 to species level.

Clinical isolates are received at the Pneumococcal Reference Laboratory, Madrid, Spain, for typing purposes and antibiotic resistance surveillance. Isolates are routinely confirmed to be S. pneumoniae by colony morphology on blood agar, OPT susceptibility, and sodium deoxycholate solubility. Two of these isolates, which were isolated from sputum samples from patients with pneumonia and identified at the hospital laboratory as Opts S. pneumoniae strains (OPT disk inhibition zone diameters, 14 mm for isolate 1174/97 and 20 mm for isolate 1162/99), drew our attention since they were insoluble in sodium deoxycholate. In addition, their DNAs did not hybridize with the pnl-, lytA-, and pneumococcus ribosomal DNA (AccuProbe)-specific probes (data not shown). On the other hand, phenotypic characterization of Opts isolates 1174/97 and 1162/99 with the API 32 Strep system classified them as S. oralis.

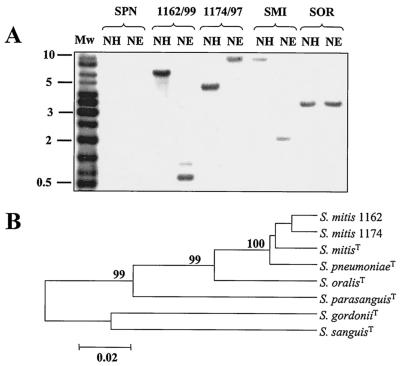

In recent work carried out in our laboratory (3), we detected an open reading frame, ant, that is not present in S. pneumoniae strains but that it is found in S. mitis and S. oralis. A probe containing this gene was used in Southern blotting experiments with chromosomal DNAs from isolates 1162/99 and 1174/99. Both Opts VS isolates, S. mitis NCTC 12261T and S. oralis NCTC 11427T, hybridized with the ant-specific probe, whereas S. pneumoniae R6 did not (Fig. 1A). The results of these experiments suggest that even though they were Opts, isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 were not pneumococcal strains. To determine the phylogenetic positions of strains 1162/99 and 1174/97 among VS, we amplified and sequenced a 1,138-nucleotide internal fragment of the genes encoding their 16S rRNAs (data not shown). Sequence comparison revealed more than 99% identity with the 16S rRNA genes of S. pneumoniae, S. mitis, and S. oralis, whereas lower levels of similarity (98.2 to 97.6%) with other species of the mitis group (Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus sanguis, and Streptococcus parasanguis) were found, indicating that isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 belong to the mitis group of VS (19). Recent investigations (20, 32) have shown that sequence analysis of sodA is a faithful method for identification of species within the mitis group. The sequences of an internal portion of sodA (366 bp) of strains 1162/99 and 1174/97 were determined and compared with those of laboratory strain R6, S. pneumoniae NCTC 7465T, S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. oralis NCTC 11427T, S. gordonii ATCC 10558T, S. sanguis ATCC 10556T, and S. parasanguis ATCC 15910T. The sodA sequences of 1162/99 and 1174/97 were very similar (98.1% identical) and showed high degrees of similarity (greater than 96%) with those of S. mitis NCTC 12261T and S. pneumoniae strains (Fig. 1B). Lower degrees of similarity were found with other species of the S. mitis group: less than 93, 83, 82, and 88% similarity with S. oralis NCTC 11427T, S. gordonii, S. sanguis, and S. parasanguis, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Identification of VS by hybridization with a specific DNA probe (A) and identification as S. mitis by sequencing of sodA (B). (A) Chromosomal DNAs from S. pneumoniae R6 (SPN), S. mitis NCTC 12261T (SMI), S. oralis NCTC 11427T (SOR), and isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 were cleaved with NheI plus HindIII (lanes NH) or NheI plus EcoRV (lanes NE), and the fragments were separated in 1% agarose gels. Lane Mw, biotinylated DNA ladder. The gel was blotted, and the blot was probed with a 798-bp biotinylated fragment containing most of the ant gene. (B) Tree of 365-bp sodA fragments obtained by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages. The sequences of strains 1162/99 and 1174/97 were compared with those of the type strains of S. mitis (NCTC 12261), S. pneumoniae (NCTC 7465), S. oralis (NCTC 11427), S. parasanguis (ATCC 15912), S. gordonii (ATCC 10558), and S. sanguis (ATCC 10556). Phylogenetic analyses were conducted with the MEGA program (version 2.1) by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages. Only bootstrap confidence intervals exceeding 90% are shown.

Taken together, these results classified isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 as S. mitis.

Susceptibilities of strains to amino-alcohol antimalarial drugs and sequences of atpC and atpA genes.

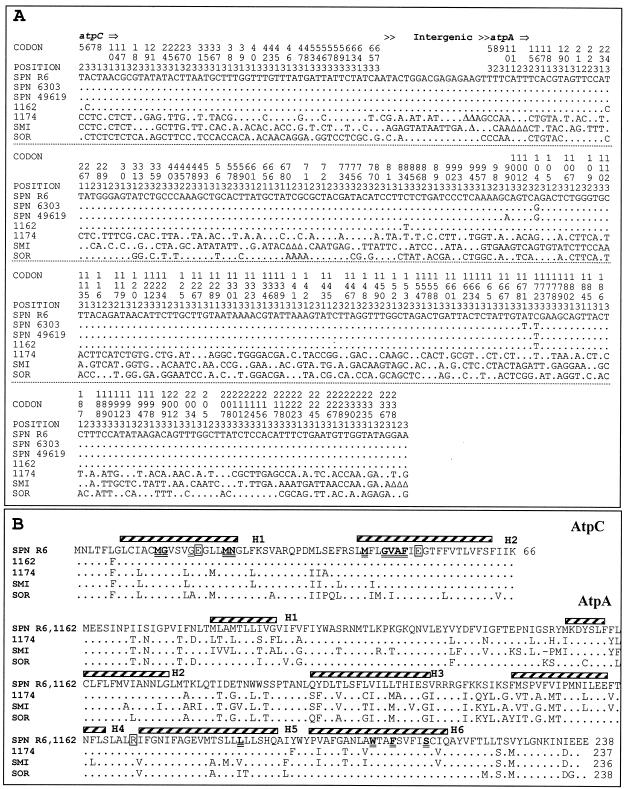

The characterization of pneumococcal strains carrying point mutations in atpC or atpA (24) provided criteria that could be used to categorize their susceptibilities to OPT, QIN, and MFL. Strains were considered susceptible when OPT MICs were ≤1.5 μg/ml, QIN MICs were ≤50 μg/ml, or MFL MICs were ≤1.25 μg/ml. MICs for intermediate susceptible strains ranged from 3 to 6 μg/ml for OPT, 100 to 200 μg/ml for QIN, and 0.31 to 0.62 μg/ml for MFL. Strains were considered resistant when OPT MICs were >6 μg/ml, QIN MICs were >200 μg/ml, or MFL MICs were >0.62 μg/ml. By these criteria, isolate 1162/99 was susceptible to OPT and QIN and intermediately susceptible to MFL (Table 2). However, isolate 1174/97 showed intermediate susceptibility to OPT and resistance to QIN and MFL (Table 2). Since the mutations involved in OPT resistance map in the atpC and atpA genes, the nucleotide sequences of these genes from the two Opts VS clinical isolates, together with those of S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303, and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619, were determined and compared to the published sequences of S. pneumoniae R6 and S. oralis NCTC 11427T (9). PCR fragments of about 1 kb were obtained by amplification of S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303 and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (by using oligonucleotides atp660 and atpB56) and S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. mitis 1162/99, and S. mitis 1174/97 (by using oligonucleotides atpWO and atpB56). Those fragments were sequenced with the same primers used in the PCR amplifications as well as with internal primers. The nucleotide sequences of the atpC and atpA genes from isolate 1162/99 showed almost complete identity with those of the S. pneumoniae strains (Fig. 2A). However, the nucleotide sequence from isolate 1174/97 showed a higher degree of identity with those of S. mitis NCTC 12261T (83.07%) and S. oralis NCTC 11427T (80.99%) than with that of S. pneumoniae (79.51%). In comparison with the S. pneumoniae R6 sequence, these nucleotide changes yielded a single amino acid change (cL6F) in the c subunit of isolate 1162/99, eight changes in isolate 1174/97 (Fig. 2B), but no changes in S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303 and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619. Two changes in the a subunit were observed in S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303 (aE104G and aD171F) and S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 (aL99I and aE104G), 52 changes were observed in 1174/99, but no changes were observed in 1162/99 (Fig. 2B).

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities of S. pneumoniae and VS strains to amino-alcohol antimalarials

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| OPT | QIN | MFL | |

| S. pneumoniae R6 | 1.5 | 50 | 0.15 |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303 | 0.75 | 25 | 0.15 |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 | 1.5 | 50 | 0.15 |

| S. mitis NCTC 12261 | 96 | 800 | 40 |

| S. oralis ATCC 10557 | 48 | 400 | 40 |

| S. oralis NCTC 11427 | 48 | 400 | 20 |

| S. mitis 1162/99 | 0.75 | 50 | 0.30 |

| S. mitis 1174/97 | 6 | 800 | 10 |

Susceptibility categorizations for OPT, QIN, and MFL: resistant, MICs of >6, >200, and >0.62 μg/ml, respectively; intermediate, MICs of 3 to 6, 100 to 200, and 0.3 to 0.6 μg/ml, respectively; susceptible, MICs of ≤1.5, ≤50, and ≤1.25 μg/ml, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence variations in the atpC and atpA genes (A) and comparisons of the amino acid sequences and the secondary structures of the c and a subunits (B) of S. pneumoniae and VS strains. (A) The nucleotides present at each polymorphic site are shown for strain R6, but for the other strains, only nucleotides that differ from those in R6 are shown. Codon numbers are indicated vertically above the sequences. Positions 1, 2, and 3 refer to the first, second, and third nucleotides in the codon, respectively. Triangles indicate gaps. (B) The predicted α helices (H1 to H6) are shown above the sequence of S. pneumoniae R6. Residues mutated in Optr strains (24) are shown in boldface and are double underlined. Residues involved in proton translocation are boxed. SPN R6, S. pneumoniae R6 (GenBank accession number Z25851); SPN 6303, S. pneumoniae ATCC 6303; SPN 49619, S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619; 1162, VS 1162/99; 1174, VS 1174/97; SMI, S. mitis NCTC 12261; and SOR, S. oralis NCTC 11427 (GenBank accession numbers Z26852 and Z26853).

Chromosomal organization of atp operon region.

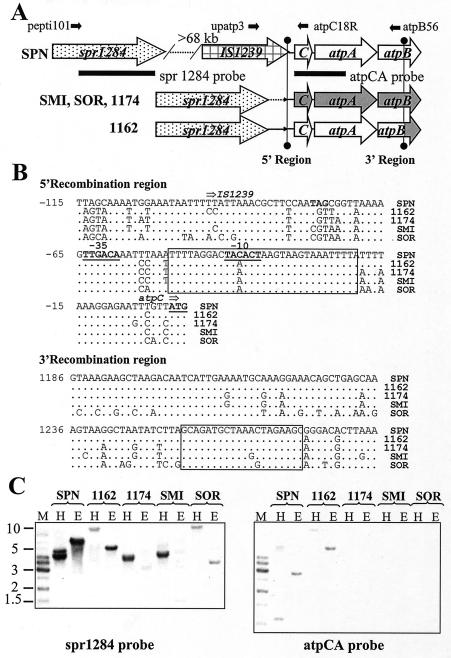

The virtual identity of the atpC and atpA sequences of S. mitis 1162/99 and S. pneumoniae led to the hypothesis that S. mitis 1162/99 may have acquired this genome region from S. pneumoniae via horizontal transfer. To test this hypothesis, the chromosomal region located 5′ of atpC was sequenced by using chromosomal DNAs from the various strains and oligonucleotides corresponding to the complementary strand of the primer coding for AtpC residues 11 to 18 (atpc18RSpn, atpc18RSmi, or atpc18RSor). Comparison of these sequences showed the presence in S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. oralis NCTC 11427T, and isolates 1162/99 and 1174/97 of a gene with a high degree of similarity (>87%) to spr1284 of S. pneumoniae R6 (16) and sp1429 of S. pneumoniae TIGR4 (39), both of which encode putative peptidases. The spr1284 gene was contiguous with atpC in VS strains but was located 68,630 bp upstream of atpC in the R6 genome and 73,606 bp upstream of atpC in the TIGR4 genome. Given the high degrees of similarity among the sequences of spr1284 of S. pneumoniae R6 and the VS, an oligonucleotide (pepti101) was designed on the basis of the spr1284 R6 sequence. Confirmation of the spr1284-atpCA gene organization in VS was obtained by PCR experiments. Amplifications with oligonucleotide pepti101, whose sequence is specific for a region in spr1284, and two oligonucleotides whose sequences are specific for a region in either atpC (atpC18RSmi) or atpB (atpB56) (Fig. 3A) rendered DNA fragments of 1.4 and 2.4 kb, respectively, for S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. mitis 1162/99, and S. mitis 1174/97. Amplification of S. oralis NCTC 11427T with oligonucleotides pepti101 and atpC18RSor yielded a 1.6-kb fragment instead of the 1.4-kb fragment observed for S. mitis NCTC 12261T, as expected from the larger size of the spr1284-atpC intergenic region of S. oralis NCTC 11427T, but no amplification with the primer pair peti101 and atpB56 was observed, probably due to the low degree of similarity between the atpB sequences of S. pneumoniae R6 and S. oralis NCTC 11427T. On the other hand, no amplification was observed for S. pneumoniae R6 with pepti101 and either atpC18RSpn or atpB56. However, PCR amplifications with an oligonucleotide specific for a region in IS1239 (upatp3) and atpC18RSpn yielded a 0.6-kb fragment for R6 and no fragment for the VS (data not shown). The PCR products resulting from these amplifications were sequenced with the same oligonucleotides used for the amplifications as well as with internal primers. A comparison of the sequences of S. pneumoniae R6 and S. mitis 1162/99 showed almost complete identity in a 50-nucleotide region located 5′ of atpC (positions 1 to −50 of the sequence in Fig. 3B) that includes the −10 region of the atp promoter. From positions −50 to −115, the sequence of S. mitis 1162/99 showed a higher degree of identity with S. mitis NCTC 12261T (93.8%) than with S. pneumoniae R6 (78.5%). In addition, the size of the spr1284-atpC intergenic region in S. oralis NCTC 11427T DNA was 242 to 260 nucleotides longer than those in the S. mitis clinical isolates and S. mitis NCTC 12261T (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Genetic structures of atp regions of S. pneumoniae and VS (A), nucleotide sequence of the region surrounding the recombination point in strain 1162/99 (B), and Southern blotting hybridizations with two different probes (C). (B) The putative recombination regions are boxed. (C) H, digestion with NheI plus HindII; E, digestion with NheI plus EcoRV; the other abbreviations are as defined in the legend to Fig. 1. The gel was blotted and the blot was probed with probe spr1284. After stripping of the blot, the blot was reprobed with probe atpCA.

Additional testing of the genetic structure of the atpC upstream chromosomal region in S. pneumoniae and the VS was carried out by Southern blotting hybridization with two probes derived from S. pneumoniae R6, one coding for Spr1284 amino acid residue positions 101 to 413 (probe spr1284) and another encoding AtpC and the first 113 residues of AtpA (probe atpCA). Probe spr1284 hybridized with the DNAs of all strains tested, indicating a high degree of sequence similarity among the spr1284 genes (Fig. 3C). However, probe atpCA hybridized only with S. pneumoniae R6 and S. mitis 1162/97 DNAs, as was expected from the low degrees of similarity among the sequences of the atpCA genes of S. pneumoniae R6 and those of the rest of the VS strains (Fig. 2A). Hybridization of probe spr1284 with S. pneumoniae R6 DNA showed two bands of 4.7 and 4.2 kb (for digestions with NheI and HindIII) and a single band of 6.5 kb (for digestions with NheI and EcoRV), whereas hybridization with probe atpCA showed bands of 1.1 kb (for digestions with NheI and HindIII) and 2.9 kb (for digestions with NheI and EcoRV), suggesting that spr1284 and atpCA are located at different chromosomal positions, in accordance with the restriction map for those enzymes in the R6 genome. However, hybridization of probe spr1284 or probe atpCA with S. mitis 1162/99 showed bands of identical sizes (11 kb for digestions with NheI and HindIII and 5.2 kb for digestions with NheI and EcoRV) (Fig. 3C), indicating that spr1284 is located near atpC and atpA in the S. mitis 1162/99 chromosome.

DISCUSSION

Natural genetic transformation is essential for the genetic plasticity of S. pneumoniae (7). Interspecies recombination events between S. pneumoniae and the genetically related VS S. oralis and S. mitis have been described for the penicillin-binding protein-encoding genes (13, 37) and the fluoroquinolone target genes (4, 11). In these cases, interchanges have been detected in the presence of intense selective pressure. This does not imply, however, that other interchanges, both inter- and intraspecific, in genes not involved in antimicrobial resistance are occurring, as is the case for the genes encoding the capsular types (8), the comCDE loci required for competence (14), and the genes of the F0 complex of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of S. mitis 1162/99, as shown in this work. A comparison of the chromosomal organization of the atp operon regions in S. pneumoniae, VS strains, and S. mitis Opts strains (Fig. 2), together with that of the nucleotide sequence of the atpC-atpA-atpB region, strongly suggests a recombinational origin for strain 1162/99. That recombination resulted in the acquisition of a region of about 1.3 kb that includes the complete atpC and atpA genes and of 300 bp of atpB from S. pneumoniae. That interchange is responsible for the Opts phenotype of S. mitis 1162/99 (Table 1), since the F0 complex (c, a, and b subunits) of the F0F1 H+-ATPase is responsible for that phenotype. Although the mutations conferring OPT resistance map in atpC and atpA (9, 24, 28, 31), it is well known that the b subunit is required for H+ translocation (36). The structure of the Escherichia coli subunit b dimer consists of a single 33-amino-acid residue transmembrane helix at its N-terminal region that interacts with F0 subunit a and a 123-residue cytoplasmic domain that binds to the δ subunit and to one of the α subunits of F1 (2, 15, 34). This structure is shared by the b subunits of S. pneumoniae, S. mitis NCTC 12261T, S. oralis NCTC 11427T, S. mitis 1162/99, and S. mitis 1174/97 (data not shown). The N-terminal part of atpB of pneumococcal origin that is present in S. mitis 1162/99 includes the coding region of the first 100 amino acid residues of the b subunit in which the transmembrane helix (residues 6 to 26) that interacts with the a subunit is located. The same occurred in an Optr recombinant laboratory strain (S. pneumoniae M222) that we constructed by genetic transformation of S. pneumoniae R6 with DNA from S. oralis NCTC 11427T (9). Comparisons of the atp sequences of these strains and that of S. mitis 1162/99 showed that the same region of the atp operon was involved in the interchanges that yielded Optr S. pneumoniae M222 and Opts S. mitis 1162/99: the complete atpC and atpA genes and 300 bp of the 5′ end of atpB. These results suggest that the organization of a functional F0F1 ATPase in both recombinant strains requires a b subunit with an N terminus compatible with the a subunit and a C terminus compatible with the δ subunit. In this way, in S. mitis 1162/99, the N termini of the b, a, and c subunits are of pneumococcal origin, whereas the C termini of the b and δ subunits are of VS origin. Likewise, S. pneumoniae M222 had c and a subunits and the 5′ end of the b subunits of S. oralis NCTC 11427T, whereas the δ subunit (and the rest of the F1 subunits) came from S. pneumoniae R6. The simultaneous interchange of the c and a subunits also seems to be a requisite for proper functioning of the F0 complex. The 5′ point of recombination in S. mitis 1162/99 would be at a 31-bp sequence located upstream of atpC that is identical in S. pneumoniae and all VS strains studied, with the exception of a single change in S. pneumoniae strains (Fig. 3B). The 3′ point of recombination in both S. mitis 1162/99 and S. pneumoniae M222 would be at a 20-bp sequence in atpB that is almost identical in S. pneumoniae and the VS strains studied (Fig. 3B). The sizes of these recombination regions are close to the minimal size of an efficient processing segment required for recombination in S. pneumoniae, which is about 30 bp (17).

On the other hand, intermediate Opts isolate 1174/97 has an atpCA sequence compatible with a VS species and several amino acid changes in its c and a subunits compared with the sequences of S. pneumoniae, S. mitis NCTC 12261T, and S. oralis NCTC 11427T (Fig. 2B). Among the amino acid residues of the c and a subunits known to be involved in the Optr-Opts phenotype of S. pneumoniae (9, 24, 28, 31), there is only one residue that was changed in S. oralis NCTC 11427T and S. mitis NCTC 12261T but that was conserved in S. pneumoniae and S. mitis 1174/97: residue L186 of the a subunit. An L186P change has been shown to be responsible for the intermediate Opts phenotype (MIC, 6 μg/ml, which is the same as that observed for strain 1174/97) of S. pneumoniae MJM21 (24). That residue is located in α helix 5 of the a subunit, which includes residues 172 to 191 (24). Identity was observed between the α helix 5 sequences of S. pneumoniae and S. mitis 1174/97, while several changes were present in the α helix 5 sequences of S. mitis NCTC 12261T and S. oralis NCTC 11427T compared with that of S. pneumoniae. The identity found between the α helix 5 sequence of S. mitis 1174/97 and that of S. pneumoniae could be responsible for the intermediate Opts phenotype of S. mitis 1174/97.

At present, most clinical laboratories depend on the OPT susceptibility test for S. pneumoniae identification. Accordingly, the two Opts VS strains described in this work, the fully Opts VS and the intermediate Opts VS, were identified as S. pneumoniae by the clinical laboratories that had sent them to the reference laboratory. Since misidentification of Opts VS as S. pneumoniae may have significant implications for the management of patients, the performance of at least two tests for the identification of S. pneumoniae, i.e., OPT susceptibility testing and bile solubility testing, is strongly recommended.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. García for critical reading of the manuscript. The technical assistance of G. Asensio and A. Rodríguez-Bernabé is acknowledged.

A.J.M.-G. and L.B. received fellowships from the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, respectively. This study was supported by grant 1274/01 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and grant BIO2002-01398 from the Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams, J. P., A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1994. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature 370:621-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aris, J. P., and R. D. Simoni. 1983. Cross-linking and labeling of the Escherichia coli F1F0-ATP synthase reveal a compact hydrophylic portion of F0 close to an F1 catalytic subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 258:14599-14609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balsalobre, L., M. J. Ferrandiz, J. Liñares, F. Tubau, and A. G. de la Campa. 2003. Viridans group streptococci are donors in horizontal transfer of topoisomerase IV genes to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2072-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bast, D. J., J. C. S. de Azevedo, T. Y. Tam, L. Kilburn, C. Duncan, L. A. Mandell, R. J. Davidson, and D. E. Low. 2001. Interspecies recombination contributes minimally to fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2631-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borek, A. P., D. C. Dressel, J. Hussong, and L. R. Peterson. 1997. Evolving clinical problems with Streptococcus pneumoniae: increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents, and failure of traditional optochin identification in Chicago, Illinois, between 1993 and 1996. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 29:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. 1997. Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46:1-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Claverys, J. P., M. Prudhomme, I. Mortier-Barriere, and B. Martin. 2000. Adaptation to the environment: Streptococcus pneumoniae, a paradigm for recombination-mediated genetic plasticity? Mol. Microbiol. 35:251-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffey, T. J., M. C. Enright, M. Daniels, J. K. Morona, R. Morona, W. Hryniewicz, J. C. Paton, and B. G. Spratt. 1998. Recombinational exchanges at the capsular polysaccharide biosynthetic locus leading to frequent serotype changes among natural isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenoll, A., R. Muñoz, E. García, and A. G. de la Campa. 1994. Molecular basis of the optochin-sensitive phenotype of pneumococcus: characterization of the genes encoding the F0 complex of the Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus oralis H+-ATPases. Mol. Microbiol. 12:587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrándiz, M. J., and A. G. de la Campa. 2002. The membrane-associated F0F1 ATPase is essential for the viability of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 212:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrandiz, M. J., A. Fenoll, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Horizontal transfer of parC and gyrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:840-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.González, I., M. Georgiou, F. Alcaide, D. Balas, J. Liñares, and A. G. de la Campa. 1998. Fluoroquinolone resistance mutations in the parC, parE, and gyrA genes of clinical isolates of viridans group streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2792-2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakenbeck, R., K. Kaminski, A. Köning, M. Van der Linden, J. Paik, P. Reichmann, and D. Zähner. 2000. Penicillin-binding proteins in β-lactam-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, p. 433-441. In A. Tomasz (ed.), Streptococcus pneumoniae: molecular biology and mechanism of disease. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., Larchmont, N.Y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Håvarstein, L. S., R. Hakenbeck, and P. Gaustad. 1997. Natural competence in the genus Streptococcus: evidence that streptococci can change pherotype by interspecies recombinational exchanges. J. Bacteriol. 179:6589-6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermolin, J., J. Gallant, and R. H. Fillingame. 1983. Topology, organization, and function of the psi subunit in the F0 sector of the H+-ATPase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 258:14550-14555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D. J. Fu, W. Fuller, C. Geringer, R. Gilmour, J. S. Glass, H. Khoja, A. R. Kraft, R. E. Lagace, D. J. LeBlanc, L. N. Lee, E. J. Lefkowitz, J. Lu, P. Matsushima, S. M. McAhren, M. McHenney, K. McLeaster, C. W. Mundy, T. I. Nicas, F. H. Norris, M. O'Gara, R. B. Peery, G. T. Robertson, P. Rockey, P. M. Sun, M. E. Winkler, Y. Yang, M. Young-Bellido, G. Zhao, C. A. Zook, R. H. Baltz, S. R. Jaskunas, P. R. Rosteck, P. L. Skatrud, and J. I. Glass. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Humbert, O., M. Prudhomme, R. Hakenbeck, C. G. Dowson, and J.-P. Claverys. 1995. Homologous recombination and mismatch repair during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: saturation of the Hex mismatch repair system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9052-9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakinuma, Y. 1998. Inorganic cation transport and energy transduction in Enterococcus hirae and other streptococci. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1021-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawamura, Y., X.-G. Hou, F. Sultana, H. Miura, and T. Ezaki. 1995. Determination of 16S rRNA sequences of Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus gordonii and phylogenetic relationships among members of the genus Streptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:406-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamura, Y., R. A. Whiley, S.-E. Shu, T. Ezaki, and H. J. M. 1999. Genetic approaches to the identification of the mitis group within the genus Streptococcus. Microbiology 145:2605-2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontiainen, S., and A. Sivonen. 1987. Optochin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae strains isolated from blood and middle ear fluid. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 6:422-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunin, C. M., and W. Y. Ellis. 2000. Antimicrobial activities of mefloquine and a series of related compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:848-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund, E., and J. Henrichsen. 1978. Laboratory diagnosis, serology and epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Methods Microbiol. 12:241-262. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martín-Galiano, A. J., B. Gorgojo, C. M. Kunin, and A. G. de la Campa. 2002. Mefloquine and new related compounds target the F0 complex of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1680-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martín-Galiano, A. J., M. J. Ferrándiz, and A. G. de la Campa. 2001. The promoter of the operon encoding the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is inducible by pH. Mol. Microbiol. 41:1327-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore, H. F., and A. M. Chesney. 1917. A study of ethylhydrocuprein (optochin) in the treatment of acute lobar pneumonia. Arch. Intern. Med. 19:611-682. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muñoz, R., A. Fenoll, D. Vicioso, and J. Casal. 1990. Optochin-resistant variants of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13:63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muñoz, R., E. García, and A. G. de la Campa. 1996. Quinine specifically inhibits the proteolipid subunit of the F0F1 H+-ATPase of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 178:2455-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 30.Phillips, G., R. Barker, and O. Brogan. 1988. Optochin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Lancet ii:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pikis, A., J. M. Campos, W. J. Rodriguez, and J. M. Keith. 2001. Optochin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae: mechanism, significance, and clinical implications. J. Infect. Dis. 184:582-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poyart, C., G. Quesne, S. Coulon, P. Berche, and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Identification of streptococci to species level by sequencing the gene encoding the manganese-dependent superoxide dismutase. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:41-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rastogi, V. K., and M. E. Girvin. 1999. Structural changes linked to proton translocation by subunit c of the ATP synthase. Nature 402:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodgers, A. J., S. Wilkens, R. Aggeler, M. B. Morris, S. M. Howitt, and R. A. Capaldi. 1997. The subunit δ-subunit b domain of the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATPase. The β subunits interact with F1 as a dimer and through the δ subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31058-31064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Schneider, E., and K. Altendorf. 1984. Subunit b of the membrane moiety (F0) of ATP synthase (F1F0) from Escherichia coli is indispensable for H+ translocation and binding of the water-soluble F1 moiety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:7279-7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spratt, B. G. 1994. Resistance to antibiotics mediated by target alterations. Science 264:388-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stock, D., A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 1999. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286:1700-1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. Gwinn, J. F. Kolonay, W. C. Nelson, J. D. Peterson, L. A. Umayam, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, M. R. Lewis, D. Radune, E. Holtzapple, H. Khouri, A. M. Wolf, T. R. Utterback, C. L. Hansen, L. A. McDonald, T. V. Feldblyum, S. Angiuoli, T. Dickinson, E. K. Hickey, I. E. Holt, B. J. Loftus, F. Yang, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, B. A. Dougherty, D. A. Morrison, S. K. Hollingshead, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsai, H.-Y., P.-R. Hsueh, L.-J. Teng, P.-I. Lee, L.-M. Huang, C.-Y. Lee, and K.-T. Luh. 2000. Bacteremic pneumonia caused by a single clone of Streptococcus pneumoniae with different optochin susceptibilities. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:458-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]