Abstract

OmpK35 from Klebsiella pneumoniae is the homologue of Escherichia coli OmpF porin. Expression of OmpK35 in K. pneumoniae strain CSUB10R (lacking both OmpK35 and OmpK36) decreased the MICs of cephalosporins and meropenem ≥128-fold and decreased the MICs of imipenem, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol ≥8-fold. MIC reductions by OmpK35 were 4 times (cefepime), 8 times (cefotetan, cefotaxime, and cefpirome), or 128 times (ceftazidime) higher than those caused by OmpK36, but the MICs were similar or 1 dilution lower for other evaluated agents.

Klebsiella pneumoniae produces two major porins (OmpK35 and OmpK36) and the quiescent porin OmpK37. Details on OmpK36 and OmpK37 have been previously reported (1, 6, 10). Most clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae lacking extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) express both OmpK35 and OmpK36 porins, while most ESBL-expressing K. pneumoniae clinical isolates produce only OmpK36 (9). Until now, the few clinical isolates lacking both OmpK35 and OmpK36 have been ESBL-producing strains (14).

Loss of OmpK36 is related to cefoxitin resistance and increased resistance to oxyimino- and zwitterionic cephalosporins in strains producing ESBL and to carbapenem resistance in strains producing plasmid-mediated AmpC-type β-lactamase (3, 4, 13, 15). Loss of OmpK36 also results in a moderate increase in fluoroquinolone resistance in strains with altered topoisomerases and/or active efflux of quinolones.

Preliminary results (6) indicate that OmpK35 allows efficient penetration of cefoxitin, cefotaxime, and carbapenems, but there has been some controversy on the role of this porin in cephalosporin penetration in K. pneumoniae (18). Detailed studies on the importance of OmpK35 in antimicrobial resistance are lacking.

In order to investigate the role of OmpK35 in antimicrobial resistance, we cloned the ompK35 gene. For this purpose, genomic DNA from K. pneumoniae strain KT755 (19) was digested with Sau3A. Fragments were ligated to cosmid pLA2917 (2) and used to transform Escherichia coli DH5α (17). Recombinants were screened for ompK35 by PCR using primers U681 (5′-CGG TTA CGG CCA GTG GGA ATA-3′) and L1316 (5′-GAC GCA GAC CGA AAT CGA ACT-3′), specific for enterobacterial porins and located 215 and 850 bp downstream of the ompK36 start codon, respectively (6). The sizes of PCR-amplified products from ompF-type genes are different from those of other porin genes (data not shown). One clone carrying a plasmid, designated pSHA15, produced an amplicon of the desired size. Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) were isolated as described previously (1, 13). Western blot analysis of OMPs was performed on Immobilon P filters (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) using anti-OmpK35 antibody (diluted 1:1,000) and alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (diluted 1:5,000) (13).

OMP profiles of E. coli DH5α carrying pSHA15 exhibited a band with the same mobility as that of OmpK35 expressed by K. pneumoniae KT755 (data not shown). The expression of OmpK35 was downregulated in a high-osmolarity culture medium, as occurs with the OmpF-like porins (9), and OmpK35 reacted with anti-OmpK35 in immunoblot experiments (data not shown). The OmpK35 protein expressed by the E. coli clone was extracted by porin extraction methods based on the trypsin resistance of porins and their strong noncovalent association with the peptidoglycan, and it also retained its heat modifiability.

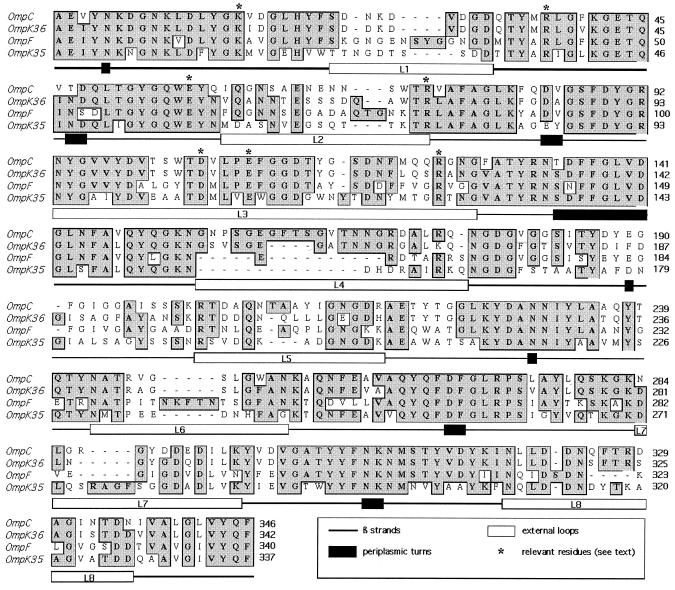

The ompK35 gene of K. pneumoniae KT755 was sequenced (EMBL database accession no. AJ011501). The amino acid sequence of OmpK35 was aligned with the sequences of other enterobacterial porins (5, 7) (Fig. 1) on the basis of the conservation of the β-strands and some key residues that are well conserved in porins: Lys16, Arg38, Glu58, Arg75, Asp106, Glu110, and Arg126. OmpK35 is an OmpF homologue and presents a typical 16 β-strand structure, with eight short periplasmic turns and eight extracellular loops of variable lengths. OmpK35 loop 3, which defines the size of the transmembrane pore in other porins, extends inside the barrel and is the most conserved loop and contains only one more residue than OmpF and OmpC from E. coli and OmpK36 from K. pneumoniae.

FIG. 1.

Comparison by alignment of the deduced OmpK35 sequence from K. pneumoniae with the sequences of OmpF and OmpC from E. coli and OmpK36 from K. pneumoniae available in GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ. Secondary structure motifs are described on the basis of the crystal structure of OmpK36. The numbering is based on the mature OmpK36. Conserved amino acids (shaded and boxed) and gaps introduced to maximize alignment (hyphens) are indicated.

For susceptibility testing experiments, the ompK35 gene was cloned in pWSK30 (20) and endowed with a kanamycin resistance cassette from pCS12 (8) to give pSHA16K. The pSHA16K plasmid was cloned into the porin-deficient K. pneumoniae CSUB10R clinical isolate and into the clonally related (3) isolate K. pneumoniae CSUB10S (expressing OmpK36). The expression of OmpK35 does not interfere with β-lactamase activity in CSUB10R, as determined spectrophotometrically with crude supernatants from sonicated cells as the enzyme source (15) (data not shown).

MICs of cefoxitin (Sigma, Madrid, Spain), cefotetan (Zeneca, Madrid, Spain), ceftazidime (Glaxo, Barcelona, Spain), cefotaxime (Sigma), cefepime (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Madrid, Spain), cefpirome (Hoechst Marion-Roussel, Romainville, France), imipenem (Merck Sharp & Dohme, Madrid, Spain), meropenem (Zeneca), ciprofloxacin (Sigma), clinafloxacin (Parke-Davis, Ann Arbor, Mich.), amikacin (Sigma), gentamicin (Sigma), tetracycline (Sigma), and chloramphenicol (Sigma) for strains CSUB10S and CSUB10R and OmpK35-expressing transconjugants derived from these two strains (Table 1) were determined by microdilution, according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) guidelines (16). Antimicrobial agent MICs for K. pneumoniae CSUB10R containing plasmids pKSK (vector) and pSHA25K (OmpK36) were also determined for comparison.

TABLE 1.

MICs of antimicrobial agents against K. pneumoniae strains with different patterns of porin expression

| Strain | Porin(s) | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOX | CTT | CAZ | CTX | FEP | PIR | IPM | MEM | CIP | CLX | AMK | GEN | TET | CHL | ||

| CSUB10S | OmpK36 | 2 | 0.06 | 256 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 16 |

| CSUB10R | None | 128 | 32 | >512 | 512 | 512 | 512 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0.125 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 64 |

| CSUB10R/pSHA16K | OmpK35 | 1 | 0.03 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| CSUB10R/pSHA25K | OmpK36 | 2 | 0.125 | 256 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | 16 |

| CSUB10S/pSHA16K | OmpK35 and OmpK36 | 1 | 0.03 | 4 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 |

| CSUB10R/pKSK | None | 128 | 16 | >512 | 256 | 128 | 256 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0.125 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 64 |

Abbreviations: FOX, cefoxitin; CTT, cefotetan; CAZ, ceftazidime; CTX, cefotaxime; FEP, cefepime; PIR, cefpirome; IPM, imipenem; MEM, meropenem; CIP; ciprofloxacin; CLX, clinafloxacin; AMK, amikacin; GEN, gentamicin; TET, tetracycline; CHL, chloramphenicol.

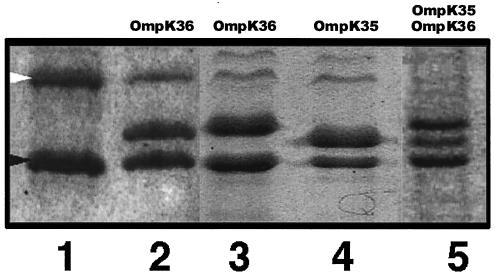

Expression of OmpK35 in K. pneumoniae CSUB10R reduced (Fig. 2) the MICs of all agents tested two or more times. The highest reductions (≥128-fold) were observed for cephamycins, oxyimino-cephalosporins, zwitterionic cephalosporins, and meropenem. Significant reductions (≥8-fold) were also noted for imipenem, ciprofloxacin, and chloramphenicol. The lowest reductions were obtained for those agents to which K. pneumoniae CSUB10R was already susceptible: clinafloxacin, tetracycline, amikacin, and gentamicin. Expression of OmpK36 in CSUB10R also decreased the MICs of all antimicrobial agents tested, except clinafloxacin, to values similar to the MICs for the related clinical isolate CSUB10S. MIC reductions caused by OmpK35 expression were 4 times (cefepime), 8 times (cefotetan, cefotaxime, and cefpirome), or 128 times (ceftazidime) higher than those caused by OmpK36 expression. These results, however, do not necessarily mean that OmpK35 should be considered specific for these agents, as expression of OmpK36 also significantly reduced their MICs. MIC reductions caused by OmpK35 were the same (meropenem, amikacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline) or 1 dilution step lower (cefoxitin, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, clinafloxacin, and chloramphenicol) than those caused by OmpK36.

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic analysis of OMPs from K. pneumoniae strain CSUB10R (lane 1) and clones derived from CSUB10R carrying plasmids pSHA25K (lane 3) and pSHA16K (lane 4). K. pneumoniae isolate CSUB10S and its clone carrying pSHA16K are also shown in lanes 2 and 5, respectively. Porins expressed by each strain are indicated above each lane. The positions of LamB (white arrowhead) and OmpA (black arrowhead) homologues of K. pneumoniae are indicated to the left of lane 1.

Expression of OmpK35 in K. pneumoniae CSUB10S, leading to the simultaneous expression of the two major porins of K. pneumoniae (Fig. 2), resulted in the MICs of the evaluated agents being the same or one dilution step higher than those against the transformant expressing only OmpK35.

Expression of both OmpK35 and to a lesser extent OmpK36 decreases the MICs of ciprofloxacin for K. pneumoniae CSUB10R (which contains a Ser83Phe change in the A subunit of DNA gyrase and expresses active efflux of fluoroquinolones [12]), indicating that both porins allow penetration of this drug. Porin expression was minimally relevant for the activity of clinafloxacin, a fluoroquinolone much more active against CSUB10R than ciprofloxacin. OmpK35 and OmpK36 expression also decreased the MICs of tetracycline and chloramphenicol. These data support the general role of both porins as hydrophilic pores. MICs of aminoglycosides did not significantly change after porin expression, presumably because of the penetration of these agents by porin-independent pathways.

Most ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains lack OmpK35 (11). Loss of this porin may be one of the factors contributing to antimicrobial resistance in ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae and may favor the selection of additional mechanisms of resistance, including loss of OmpK36 and/or active efflux (14).

OmpK35 is not normally expressed in high-osmolarity media, which may result in repression of its expression in K. pneumoniae in vivo. This may be of therapeutic importance because of the limited entrance of certain antimicrobial agents in K. pneumoniae. New studies on porin expression in K. pneumoniae grown in vivo are needed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias of the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo of Spain to L.M.-M. and V.J.B and Plan Nacional de I+D (Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología) to J.M T. A.D.-S. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura of the Spanish government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertí, S., F. Rodríguez-Quiñones, T. Schirmer, G. Rummel, J. M. Tomás, J. P. Rosenbusch, and V. J. Benedí. 1995. A porin from Klebsiella pneumoniae: sequence homology, three-dimensional model, and complement binding. Infect. Immun. 63:903-910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen, L. N., and R. S. Hanson. 1985. Construction of broad-host-range cosmid cloning vectors: identification of genes necessary for growth of Methylobacterium organophilum on methanol. J. Bacteriol. 161:955-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardanuy, C., J. Liñares, M. A. Domínguez, S. Hernández-Allés, V. J. Benedí, and L. Martínez-Martínez. 1998. Outer membrane profiles of clonally related Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from clinical samples and activities of cephalosporins and carbapenems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1636-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, P. A., C. Urban, N. Mariano, S. J. Projan, J. J. Rahal, and K. Bush. 1997. Imipenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae is associated with the combination of ACT-1, a plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase, and the loss of an outer membrane protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:563-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowan, S. W., T. Schirmer, G. Rummel, M. Steiert, R. Ghosh, R. A. Pauptit, J. N. Jansonius, and J. P. Rosenbusch. 1992. Crystal structures explain functional properties of two E. coli porins. Nature 358:727-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doménech-Sánchez, A., S. Hernández-Allés, L. Martínez-Martínez, V. J. Benedí, and S. Albertí. 1999. Identification and characterization of a new porin gene of Klebsiella pneumoniae: its role in β-lactam antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 181:2726-2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutzler, R., G. Rummel, S. Albertí, S. Hernández-Allés, P. Phale, J. Rosenbusch, V. Benedí, and T. Schirmer. 1999. Crystal structure and functional characterization of OmpK36, the osmoporin of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Structure Fold Des. 7:425-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhai, J., and C. P. Wolk. 1988. A versatile class of positive-selection vectors based on the nonviability of palindrome-containing plasmids that allows cloning into long polylinkers. Gene 68:119-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hernández-Allés, S., S. Albertí, D. Alvarez, A. Doménech-Sánchez, L. Martínez-Martínez, J. Gil, J. M. Tomás, and V. J. Benedí. 1999. Porin expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiology 145:673-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernández-Allés, S., S. Albertí, M. D. Alvarez, L. Martínez-Martínez, J. Gil, J. M. Tomás, and V. J. Benedí. 1995. Isolation of FC3-11, a bacteriophage specific for the Klebsiella pneumoniae porin OmpK36, and its use for the isolation of porin-deficient mutants. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:399-406. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernández-Allés, S., M. Conejo, A. Pascual, J. M. Tomás, V. J. Benedí, and L. Martínez-Martínez. 2000. Relationship between outer membrane alterations and susceptibility to antimicrobial agents in isogenic strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:273-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Martínez, L., I. García, S. Ballesta, V. J. Benedí, S. Hernández-Allés, and A. Pascual. 1998. Energy-dependent accumulation of fluoroquinolones in quinolone-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1850-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Martínez, L., S. Hernández-Allés, S. Albertí, J. M. Tomás, V. J. Benedí, and G. A. Jacoby. 1996. In vivo selection of porin-deficient mutants of Klebsiella pneumoniae with increased resistance to cefoxitin and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:342-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, M. C. Conejo, I. García, P. Joyanes, A. Doménech-Sánchez, and V. J. Benedí. 2002. Energy-dependent accumulation of norfloxacin and porin expression in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and relationship to extended-spectrum β-lactamase production. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3926-3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martínez-Martínez, L., A. Pascual, S. Hernández-Allés, D. Alvarez-Díaz, A. I. Suárez, J. Tran, V. J. Benedí, and G. A. Jacoby. 1999. Roles of β-lactamases and porins in activities of carbapenems and cephalosporins against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1669-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 17.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 18.Siu, L. K. 2001. Is OmpK35 specific for ceftazidime penetration? Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1601-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomás, J. M., V. J. Benedí, B. Ciurana, and J. Jofre. 1986. Role of capsule and O antigen in resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae to serum bactericidal activity. Infect. Immun. 54:85-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]