Abstract

Combinations of flucytosine with conventional and new antifungals were evaluated in vitro against 30 clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. Synergy determined by checkerboard analysis was observed with combinations of fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin with flucytosine against 77, 60, 80, 77, and 67% of the isolates, respectively. Antagonism was never observed. Killing curves showed indifferent interactions between triazoles and flucytosine and synergy between amphotericin B and flucytosine.

Infections caused by Cryptococcus neoformans have become a major problem, especially for patients with AIDS. With the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Western countries, the incidence of cryptococcosis has decreased in AIDS patients (15) but is still associated with high mortality. Amphotericin B (AMB), fluconazole (FCZ), and flucytosine (5FC) are the most commonly used antifungals to treat cryptococcosis (7, 24). New azoles, like voriconazole (VRZ), have potent in vitro activity against C. neoformans (20). Caspofungin (CAS), a new antifungal with broad-spectrum activity, showed poor activity against C. neoformans in vitro (3) and in vivo (1), but it has been shown to improve the in vitro activity of AMB or FCZ (9). The potential role of these new drugs used in combination for the management of C. neoformans infections remains to be determined.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the activity of 5FC in combination with conventional or new antifungals against the same panel of clinical isolates of C. neoformans. Antifungal interactions were tested by a broth microdilution technique, performed according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards M27-A document (16), modified for checkerboard studies. Interpretation was made by calculation of fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FICI). Time-kill studies were also performed (8).

Thirty clinical isolates of C. neoformans from our private collection were studied. Two quality control strains (16) were included in each series of experiments.

FCZ (Pfizer Ltd., Sandwich, United Kingdom), itraconazole (ITZ) (Jansen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium), VRZ (Pfizer), AMB (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and CAS (Merck and Co., Rahway, N.J.) were all tested in combination with 5FC (Sigma). The final concentrations were 32 to 0.06 μg/ml for 5FC, 32 to 0.5 μg/ml for CAS, 1 to 0.015 μg/ml for ITZ, 0.125 to 0.0019 μg/ml for VRZ, and 2 to 0.03 μg/ml for AMB. For FCZ, final concentrations were 32 to 0.5 μg/ml or 2 to 0.03 μg/ml, depending on the susceptibilities of the strains. The final inoculum in each well was 1.0 × 103 to 5.0 × 103 CFU/ml. Trays were incubated at 35°C for 72 h, and MICs were recorded spectrophotometrically. Susceptibility tests were run in duplicate. MICs of a drug alone or in combination were defined as the minimum concentration that inhibited by 50% (or 95% for AMB alone) the growth of the organism compared to the level of growth of the control. Additionally, the minimum concentrations that inhibited growth by 95% (MIC95) were also recorded for all drugs. The FIC of each drug used in combination was calculated and added to obtain the FICI (8). The interactions were defined as synergistic if the lowest FICI was ≤0.5, additive if the FICI was >0.5 and ≤4, and antagonistic if the highest FICI was >4.

Isolate 27 was selected for time-kill studies. The starting inoculum was 1.0 × 105 CFU/ml in a final volume of 20 ml of RPMI 1640. Test suspensions were incubated at 35°C with shaking. At predetermined time points, aliquots were removed, diluted, and plated on Sabouraud agar plates in duplicate. CFU were enumerated after incubation at 35°C for 48 h. The limit of detection was 20 CFU/ml. Killing was defined as a decrease of 99.9% of the starting inoculum, and synergy was defined as a ≥2-log10 decrease in killing for a combination compared to the level of killing of the most active drug alone (8). Experiments were performed in duplicate.

Duplicate MICs of 5FC, FCZ, ITZ, VRZ, AMB, and CAS alone were within ±1 log2 dilution for 94, 87, 96, 100, 100, and 100% of the isolates, respectively.

5FC MICs ranged from 0.5 to ≥32 μg/ml, with a geometric mean MIC between 3.12 and 5.16 μg/ml. For isolates 7, 14, and 23, the MICs of 5FC were ≥32 μg/ml, and these isolates were considered to be resistant to this drug (16).

MICs ranged from 0.25 to 8, 0.03 to 0.5, 0.004 to 0.12, and 0.25 to 1 μg/ml, with geometric mean MICs of FCZ, ITZ, VRZ, and AMB of 1.95, 0.11, 0.023, and 0.62 μg/ml, respectively. For synergistic interactions, the concentrations of 5FC, FCZ, ITZ, VRZ, and AMB in combination were ≤4, ≤1, ≤0.12, ≤0.008, and ≤0.25 μg/ml, respectively. MICs of CAS ranged from 8 to 32 μg/ml, with a geometric mean MIC of 12.13 μg/ml. For combinations, the MIC of 5FC for synergistic interactions was ≤1 μg/ml and that of CAS ranged from 1 to 2 μg/ml.

Table 1 gives a summary of the interactions of the different antifungals with 5FC. The combinations of 5FC with each of the other antifungals showed synergism in more than 60% of the cases. Antagonism was never observed. With 5FC combinations with FCZ, ITZ, VRZ, and AMB, synergistic interactions were observed with two of the 5FC-resistant isolates and additivity was noted with the third isolate. With the CAS-5FC combination, additive interactions were obtained with all three isolates.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the interactions between antifungal drugs for clinical isolates of C. neoformans

| Mode of interaction | % of isolates

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5FC + FCZ (n = 30) | 5FC + ITZ (n = 25) | 5FC + VRZ (n = 30) | 5FC + AMB (n = 30) | 5FC + CAS (n = 30) | |

| Synergistic | 77 | 60 | 80 | 77 | 67 |

| Additive | 23 | 40 | 20 | 23 | 33 |

| Antagonistic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

When MIC95 were considered, antifungal interactions were mostly additive for all combinations (data not shown). Synergistic interactions were observed with ITZ (3%) and CAS (13%) but not with FCZ, VRZ, and AMB.

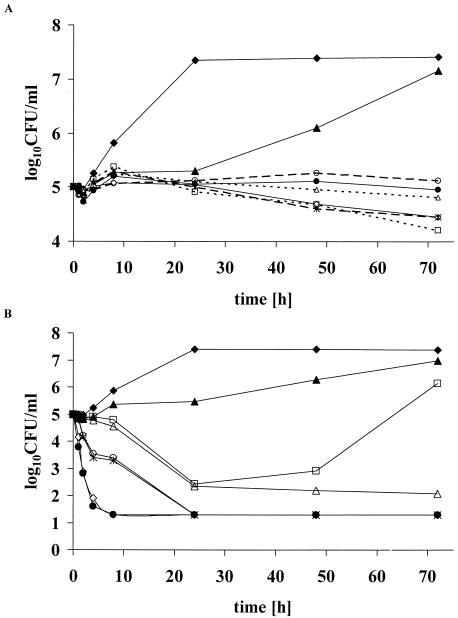

Figure 1A shows the results of the time-kill studies of the azoles. None of the three triazoles showed fungicidal activity when they were used alone. An increase in the number of CFU per milliliter with 5FC alone was observed at 48 and 72 h of incubation due to the growth of 5FC-resistant colonies. Combinations of triazoles with 5FC were neither fungicidal nor synergistic.

FIG. 1.

(A) Time-kill study with triazoles alone and in combination with 5FC on C. neoformans (isolate 27). Concentrations of 5FC, VRZ, ITZ, and FCZ alone and in combination were four, eight, eight, and four times the MIC95 as determined by the broth microdilution technique. ⧫ (solid line), control; ▴ (solid line), 5FC; ⋄ (solid line), VRZ; ×|, (dashed line), ITZ; □ (dotted line), FCZ; • (solid line), 5FC plus VRZ; ○ (dashed line), 5FC plus ITZ; Δ (dotted line), 5FC plus FCZ. (B) Time-kill study with AMB alone and in combination with 5FC on C. neoformans (isolate 27). Concentrations alone and in combination were four times the MIC95 of 5FC and two times, one times, or half the MIC95 of AMB. ⧫, control; ▴, 5FC; ⋄, AMB at twice the MIC95; ×|, AMB at the MIC95; □, AMB at half the MIC95; •, 5FC plus AMB at twice the MIC95; ○, 5FC plus AMB at the MIC95; Δ, 5FC plus AMB at half the MIC95. The limit of detection was 1.3 log10 CFU per milliliter.

As shown in Fig. 1B, AMB alone was fungicidal and killing was dose dependent. At concentrations of at least one times the MIC, the addition of 5FC did not result in a higher rate of killing. For AMB alone at a concentration of one-half the MIC, a decrease in the number of CFU per milliliter of about 2.5 logs was observed after 24 h, followed by an increase reaching at 72 h a concentration of 10 times the starting inoculum. The addition of 5FC resulted in synergy, with a decrease in the number of CFU per milliliter of about 4 logs after 72 h compared to the number with AMB alone at one-half the MIC.

Our results showed the same trends of interactions for all five combinations, even against 5FC-resistant strains. AMB in combination with 5FC is currently the “gold standard” for the treatment of cryptococcosis, as was suggested for in vitro (19) and animal (21, 22) models and demonstrated for patients (4, 26). By time-kill methodology, synergy between AMB and 5FC can be detected only at 72 h, in agreement with the results of previous studies (11, 23).

For the combination of azoles with 5FC, we found 60 to 80% of synergy by checkerboard studies, but our time-kill experiments showed no significant interaction between azoles and 5FC, as was reported by others (23). Discrepancies between results obtained by these two techniques are not unusual for fungistatic agents. A checkerboard analysis provides only static inhibitory data at one time point. In contrast, time-kill curves explore dynamic fungicidal activity over time. A previous study reported synergistic interactions between FCZ and 5FC by using checkerboard methodology (17). Murine models generally showed synergy between these two drugs (5, 6, 13, 18), while a rabbit model did not (10). In patients, a combination of FCZ and 5FC was more effective than FCZ alone (14). In a recent in vitro study, the combination of ITZ with 5FC was shown to be synergistic for 63% of the strains while antagonism was not observed (2), in agreement with our results. In animal studies, indifferent-to-synergistic interactions were found (21), but there have been no trials with humans.

Although VRZ is very active in vitro against C. neoformans (26), it is not marketed for the treatment of cryptococcosis. We found synergy between VRZ and 5FC in the checkerboard study with very low MICs alone and in combination.

Preliminary studies evaluating CAS alone showed no activity against C. neoformans (1, 3), but synergy has been reported between CAS and either AMB or FCZ in vitro (9). Here we found high MICs of CAS alone and synergy when it was used in combination with 5FC. In more than 50% of the cases the MICs of CAS in combination were in the range of achievable levels in serum (25). Nevertheless, it has to be pointed out that the high level of binding of drugs to proteins or other pharmacokinetics properties are not taken into account by in vitro tests. The potential of combination between an echinocandin and 5FC in cryptococcosis remains to be determined. In the present study, three strains were resistant to 5FC. Interestingly, interactions between 5FC and other antifungals for these strains were comparable to those obtained with susceptible strains. Although 5FC use has been advocated to be questionable when in vitro 5FC resistance is found (12), our results suggest that a combination therapy including 5FC might also be beneficial for the management of cryptococcal infections due to 5FC-resistant isolates. Nevertheless, the ability to overcome 5FC resistance may be correlated with its mechanism of resistance. If the resistance is related to a defect of intracellular penetration, the resistance may be overcome by using a drug such as AMB that favors the cellular uptake of 5FC. On the other hand, if resistance is related to a lack of deaminase, combination with a permeabilizing drug is not likely to be effective.

In conclusion, all tested combinations of 5FC with triazoles or CAS were mostly synergistic and comparable to the AMB-5FC combination. Precise relevance of these in vitro results has now to be evaluated with animal models of cryptococcosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abruzzo, G. K., A. M. Flattery, C. J. Gill, L. Kong, J. G. Smith, V. B. Pikounis, J. M. Balkovec, A. F. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, H. Rosen, H. Kropp, and K. Bartizal. 1997. Evaluation of the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872): efficacies in mouse models of disseminated aspergillosis, candidiasis, and cryptococcosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2333-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barchiesi, F., D. Gallo, F. Caselli, L. F. Di Francesco, D. Arzeni, A. Giacometti, and G. Scalise. 1999. In-vitro interactions of itraconazole with flucytosine against clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartizal, K., C. J. Gill, G. K. Abruzzo, A. M. Flattery, L. Kong, P. M. Scott, J. G. Smith, C. E. Leighton, A. Bouffard, J. F. Dropinski, and J. Balkovec. 1997. In vitro preclinical evaluation studies with the echinocandin antifungal MK-0991 (L-743,872). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2326-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, J. E., W. E. Dismukes, R. J. Duma, G. Medoff, M. A. Sande, H. Gallis, J. Leonard, B. T. Fields, M. Bradshaw, H. Haywood, Z. A. McGee, T. R. Cate, C. G. Cobbs, J. F. Warner, and D. W. Alling. 1979. A comparison of amphotericin B alone and combined with flucytosine in the treatment of cryptococcal meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 301:126-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diamond, D. M., M. Bauer, B. E. Daniel, M. A. Leal, D. Johnson, B. K. Williams, A. M. Thomas, J. C. Ding, L. Najvar, J. R. Graybill, and R. A. Larsen. 1998. Amphotericin B colloidal dispersion combined with flucytosine with or without fluconazole for treatment of murine cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:528-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding, J. C., M. Bauer, D. M. Diamond, M. A. Leal, D. Johnson, B. K. Williams, A. M. Thomas, L. Najvar, J. R. Graybill, and R. A. Larsen. 1997. Effect of severity of meningitis on fungicidal activity of flucytosine combined with fluconazole in a murine model of cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1589-1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dromer, F., S. Mathoulin, B. Dupont, O. Brugiere, L. Letenneur, et al. 1996. Comparison of the efficacy of amphotericin B and fluconazole in the treatment of cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients: retrospective analysis of 83 cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 22(Suppl. 2):S154-S160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering. 1991. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 432-492. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 9.Franzot, S. P., and A. Casadevall. 1997. Pneumocandin L-743,872 enhances the activities of amphotericin B and fluconazole against Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:331-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kartalija, M., K. Kaye, J. H. Tureen, Q. Liu, M. G. Tauber, B. R. Elliott, and M. A. Sande. 1996. Treatment of experimental cryptococcal meningitis with fluconazole: impact of dose and addition of flucytosine on mycologic and pathophysiologic outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 173:1216-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keele, D. J., V. C. DeLallo, R. E. Lewis, E. J. Ernst, and M. E. Klepser. 2001. Evaluation of amphotericin B and flucytosine in combination against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans using time-kill methodology. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 41:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1992. Principles of antifungal therapy, p. 81-102. In K. J. Kwon-Chung and J. E. Bennett (ed.), Medical mycology. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 13.Larsen, R. A., M. Bauer, J. M. Weiner, D. M. Diamond, M. E. Leal, J. C. Ding, M. G. Rinaldi, and J. R. Graybill. 1996. Effect of fluconazole on fungicidal activity of flucytosine in murine cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2178-2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayanja-Kizza, H., K. Oishi, S. Mitarai, H. Yamashita, K. Nalongo, K. Watanabe, T. Izumi, J. Ococi, K. Augustine, R. Mugerwa, T. Nagatake, and K. Matsumoto. 1998. Combination therapy with fluconazole and flucytosine for cryptococcal meningitis in Ugandan patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1362-1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirza, S. A., M. Phelan, D. Rimland, E. Graviss, R. Hamill, M. E. Brandt, T. Gardner, M. Sattah, G. P. de Leon, W. Baughman, and R. A. Hajjeh. 2003. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin. Infect. Dis. 36:789-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 17.Nguyen, M. H., F. Barchiesi, D. A. McGough, V. L. Yu, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1995. In vitro evaluation of combination of fluconazole and flucytosine against Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1691-1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen, M. H., L. K. Najvar, C. Y. Yu, and J. R. Graybill. 1997. Combination therapy with fluconazole and flucytosine in the murine model of cryptococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1120-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odds, F. C. 1982. Interactions among amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, ketoconazole, and miconazole against pathogenic fungi in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:763-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfaller, M. A., J. Zhang, S. A. Messer, M. E. Brandt, R. A. Hajjeh, C. J. Jessup, M. Tumberland, E. K. Mbidde, and M. A. Ghannoum. 1999. In vitro activities of voriconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole against 566 clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from the United States and Africa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:169-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polak, A. 1987. Combination therapy of experimental candidiasis, cryptococcosis, aspergillosis and wangiellosis in mice. Chemotherapy 33:381-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polak, A., H. J. Scholer, and M. Wall. 1982. Combination therapy of experimental candidiasis, cryptococcosis and aspergillosis in mice. Chemotherapy 28:461-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodero, L., S. Cordoba, P. Cahn, F. Hochenfellner, G. Davel, C. Canteros, S. Kaufman, and L. Guelfand. 2000. In vitro susceptibility studies of Cryptococcus neoformans isolated from patients with no clinical response to amphotericin B therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:239-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saag, M. S., R. J. Graybill, R. A. Larsen, P. G. Pappas, J. R. Perfect, W. G. Powderly, J. D. Sobel, and W. E. Dismukes. 2000. Practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30:710-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone, J. A., S. D. Holland, P. J. Wickersham, A. Sterrett, M. Schwartz, C. Bonfiglio, M. Hesney, G. A. Winchell, P. J. Deutsch, H. Greenberg, T. L. Hunt, and S. A. Waldman. 2002. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in healthy men. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:739-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Horst, C. M., M. S. Saag, G. A. Cloud, R. J. Hamill, J. R. Graybill, J. D. Sobel, P. C. Johnson, C. U. Tuazon, T. Kerkering, B. L. Moskovitz, W. G. Powderly, W. E. Dismukes, et al. 1997. Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:15-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]