Abstract

In vivo studies have described the pharmacodynamic (PD) characteristics of several triazoles. These investigations have demonstrated that the 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC ratio is the critical pharmacokinetic (PK)-PD parameter associated with treatment efficacy. Further analyses from these in vivo studies have demonstrated that a triazole free drug 24-h AUC/MIC of 20 to 25 is predictive of treatment success. We used a neutropenic murine model of disseminated Candida albicans infection to similarly characterize the PK-PD of the new triazole voriconazole. PK and PD parameters (percentage of time that the concentration remains above the MIC [T > MIC], AUC/MIC ratio, and peak level in serum/MIC ratio) were correlated with in vivo efficacy, as measured by the organism number in kidney cultures after 24 h of therapy. Voriconazole kinetics and protein binding were studied in infected neutropenic mice. Peak level/dose and AUC/dose values ranged from 0.1 to 0.2 and 0.1 to 0.7, respectively. The serum elimination half-life ranged from 0.7 to 2.9 h. The level of protein binding in mouse serum was 78%. Treatment efficacy with the four dosing intervals studied was similar, supporting the AUC/MIC ratio as the PK-PD parameter predictive of efficacy. Nonlinear regression analysis also suggested that the AUC/MIC ratio was strongly predictive of treatment outcomes (R2 for AUC/MIC ratio = 82%, R2 for peak level/MIC ratio = 63%, R2 for T > MIC = 75%). Similar studies were conducted with nine additional C. albicans isolates with various voriconazole susceptibilities (MICs, 0.007 to 0.25 μg/ml) to determine if a similar 24-h AUC/MIC ratio was associated with efficacy. The voriconazole free drug AUC/MIC ratios were similar for all of the organisms studied (range, 11 to 58; mean ± standard deviation, 24 ± 17 [P = 0.45]). These AUC/MIC ratios observed for free drug are similar to those observed for other triazoles in this model.

Several studies with antibacterial drugs have demonstrated that the pharmacokinetic (PK)-pharmacodynamic (PD) parameter predictive of in vivo efficacy is similar for drugs within the same class (4, 24). Therapeutic outcome predictions based upon these PD relationships have correlated well with the outcomes of treatment of infections caused by both susceptible and resistant pathogens (2). Furthermore, studies have suggested that the magnitude of the PK-PD parameter necessary for efficacy is relatively similar for drugs within the same class. These investigations have also shown that similar parameter magnitudes are needed to produce efficacy in different animal species, including humans.

Prior in vivo studies have demonstrated that the PK-PD parameter predictive of triazole efficacy against Candida albicans is the 24-h area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC ratio (1, 3, 12). Studies have also suggested that a 24-h AUC/MIC ratio in the range of 20 to 25 is associated with treatment efficacy in experimental in vivo models (1, 3, 19, 23; K. Sorenson, S. Corcoran, S. Chen, D. Clark, V. Tembe, O. Lomovskaya, and M. Dudley, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1271, 1999). This AUC/MIC ratio has also been shown to be predictive of outcomes in clinical trials with fluconazole (1, 10, 18; C. J. Clancy, C. A. Kauffman, A. Morris, M. L. Nguyen, D. C. Tanner, D. R. Snydman, V. L. Yu, and M. H. Nguyen, Program Abstr. 36th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am., abstr. 98, p. 93, 1998).

In the present study we have characterized the PK-PD parameter that is predictive of the efficacy of a new triazole, voriconazole, in a neutropenic murine model of disseminated candidiasis. Furthermore, we have determined the magnitude of the PK-PD parameter required to achieve efficacy for numerous C. albicans strains with various azole susceptibilities in order to provide a framework for the rational development of preliminary in vivo breakpoints for voriconazole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Ten clinical isolates of C. albicans (isolates K-1, W-2, 580, 98-17, 98-234, 98-210, 1490, 5810, 2-76, and 2183) were used. The isolates were chosen to include both fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant strains. Previous studies have shown that drug-resistant C. albicans strains are often less virulent than susceptible strains in mice. In order to limit organism virulence as a confounding variable in these studies, isolates were also chosen on the basis of a relatively similar degree of virulence in this animal model, as determined by the amount of growth in the kidneys of untreated animals over 24 h (data not shown). Isolates 1490, 580, and 2183 were kindly provided by J. Lopez-Ribot (11). Isolate 2-76 was similarly provided by T. C. White (26). The organisms were maintained, grown, subcultured, and quantified on Sabouraud dextrose agar slants (SDA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Twenty-four hours prior to study, the organisms were subcultured at 35°C.

Antifungal.

Voriconazole was obtained from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals as a powder (purity, 99.8%). Drug solutions were prepared on the day of study by dissolving the powder in 4% polyethylene glycol 400 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.).

In vitro susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined by the NCCLS M27-A method (13). Determinations were performed in duplicate on three separate occasions. Final results are expressed as the geometric means of these results.

Animals.

Specific-pathogen-free female ICR/Swiss mice (age, 6 weeks; weight, 23 to 27 g; Harlan Sprague-Dawley, Indianapolis, Ind.) were used for all studies. Animals were maintained in accordance with the criteria of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Care (14). All animal studies were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Affairs Hospital.

Infection model.

Mice were rendered neutropenic (polymorphonuclear leukocyte count, <100/mm3) by injecting cyclophosphamide (Mead Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Evansville, Ind.) intraperitoneally 4 days (150 mg/kg of body weight) and 1 day (100 mg/kg) before infection.

Organisms were subcultured on SDA 24 h prior to infection. The inoculum was prepared by placing three to five colonies into 5 ml of sterile pyrogen-free 0.9% saline warmed to 35°C. The final inoculum was adjusted to a transmittance of 0.6 at 530 nm. Fungal counts of the inoculum determined by measurement of the viable counts on SDA were 104.8 to 105.9 CFU/ml.

Disseminated infection with the Candida organisms was achieved by injection of 0.1 ml of inoculum via the lateral tail vein 2 h prior to the start of drug therapy. At the end of the study period the animals were killed by CO2 asphyxiation. After the animals were killed, the kidneys of each mouse were immediately removed and placed in sterile 0.9% saline at 4°C. The homogenate was then serially diluted 1:10, and aliquots were plated on SDA for determination of viable fungal colony counts after incubation for 24 h at 35°C. The lower limit of detection was 100 CFU/kidneys. The results were expressed as the mean number of CFU per kidneys for two mice (four kidneys).

PKs.

The single-dose PKs of voriconazole were determined in individual infected neutropenic ICR/Swiss mice following administration of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg administered in 0.2-ml volumes by oral gavage. Blood samples were collected three times by retro-orbital puncture from groups of three mice anesthetized with halothane, and the samples were placed in heparinized capillary tubes (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.). The volume collected with each sample ranged from 30 to 50 μl. Less than 5% of the total blood volume was collected from any individual mouse. The samples were collected at 1- to 2-h intervals over 5 h. Capillary tubes were immediately centrifuged (model MB centrifuge; International Equipment Co.) at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The serum samples (10 μl each) were then placed in the agar wells. The samples were analyzed by microbiologic assay. Previously described ultrafiltration methods were used for the protein binding studies (5). For the microbiologic assay, Candida kefyr ATCC 46764 was used as the assay organism in yeast nitrogen base agar supplemented with glucose and trisodium citrate (25). Assays of serum were performed and standard curves were prepared on the same day. The intraday variation was less than 5%. The lower limit of detection for this assay was 0.25 μg/ml.

PK calculations were based on a noncompartmental model. The AUC was calculated by use of the trapezoidal rule. For treatment doses for which no kinetics were determined, PK parameters were extrapolated from the values obtained in the PK studies described above.

PD parameter determination.

Neutropenic mice were infected with C. albicans K-1 2 h prior to the start of therapy. Twenty-four dosing regimens were chosen to determine the impact of dose level and dosing interval on voriconazole efficacy. These 24 regimens comprised six total dose levels (0.078, 0.3125, 1.25, 5, 20, and 80 mg/kg/24 h). The six total dose levels were fractionated by using four dosing intervals (every 3, 6, 12, and 24 h). This wide variety of regimens was used to minimize the interdependence among the three PD parameters studied. The 80-mg/kg dose was the maximum dose tolerated in this infection model. Groups of two mice were treated with each dosing regimen. The drug was administered in 0.2-ml volumes. The mice were killed at the end of therapy, and the kidneys were removed for CFU determination, as described above. Untreated control mice were killed just before treatment and at the end of the experiment. Efficacy was defined as the change in the log10 number of CFU per kidneys over the study period and was calculated by subtracting the mean log10 number of CFU per kidneys in treated mice from the mean number of CFU from the kidneys of two mice at the end of therapy in untreated animals.

PD parameter magnitude determination.

Studies similar to those described above were performed with nine additional strains of C. albicans (W-2, 580, 98-17, 98-234, 98-210, 1490, 5810, 2-76, and 2183). Attempts were made to choose organisms with various susceptibilities to voriconazole. This group of organisms included fluconazole-susceptible, fluconazole-susceptible dose-dependent, and fluconazole-resistant strains. Dosing studies were designed to vary the magnitudes of the PD parameters. The six total dose levels varied from 0.08 to 320 mg/kg/24 h. The doses were fractionated into four doses (every 6 h) for the 24-h study period. Groups of two mice were again used for each dosing regimen. At the end of study, the mice were euthanized and the kidneys were immediately processed for CFU determination.

Data analysis.

A sigmoid dose-effect model was used to measure the in vivo potency of voriconazole. The model is derived from the Hill equation: E = (Emax × DN)/(ED50N + DN), where E is the observed effect (change in the log10 number of CFU per kidneys compared with the values for the untreated controls at the end of the treatment period), D is the cumulative dose, Emax is the maximum effect, ED50 is the dose required to achieve 50% of Emax, and N is the slope of the dose-effect relationship. The correlation between efficacy and each of the three parameters studied (percentage of time that the concentration remains above the MIC [T > MIC], 24-h AUC/MIC ratio, and peak level in serum/MIC ratio [peak/MIC]) was determined by nonlinear least-squares multivariate regression analysis (Sigma Stat; Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, Calif.). The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to estimate the percent variance in the change in the log10 number of CFU per kidneys over the treatment period for the different dosing regimens that could be attributed to each of the PD parameters. Calculations were performed with both total and free drug concentrations.

To allow a more meaningful comparison of potency among the dosing regimens studied, we calculated the ED50 over the treatment period. The ED50 was chosen as an endpoint to allow comparison of the results with those of similar studies performed with the other triazoles (1). If the doses needed to achieve these benchmarks would increase significantly as the dosing interval was lengthened from every 3 h through every 24 h, the duration of time that the levels in serum remained above the MIC was the parameter predictive of efficacy. On the other hand, if the doses necessary to reach these outcomes decreased with lengthening of the dosing interval, the parameter associated with these outcomes would be the peak level in serum. If the doses remained similar, independent of changes in the dosing interval, the AUC would be predictive of efficacy.

The ED50s of the 6-h dosing regimens were determined for each of the 10 strains. The magnitude of the PD parameter predictive of the efficacy of voriconazole was then calculated for each of the 10 organisms studied to determine if a similar parameter magnitude was associated with efficacy. Again, both total and free drug concentrations were considered. The significance of differences among these values was determined by analysis of variance (Sigma Stat; Jandel Scientific Software). A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility testing.

The 48-h MICs for the 10 C. albicans organisms studied varied 35-fold (range, 0.007 to 0.25 μg/ml) (Table 1). The fluconazole MICs for this group of organisms varied more than 500-fold (range, 0.25 to >128 μg/ml).

TABLE 1.

Voriconazole efficacy against 10 C. albicans isolates in a disseminated candidiasis model

| C. albicans strain | MIC (mg/liter)

|

ED50 (mg/kg/24 h) | 24-h AUC/ MIC ratio

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voriconzole | Fluconazole | Total drug | Free drug | ||

| K1 | 0.007 | 0.25 | 7.93 | 81.4 | 17.9 |

| W2 | 0.015 | 0.5 | 14.1 | 97 | 21.2 |

| 580 | 0.03 | 4.0 | 26.3 | 237 | 52 |

| 98-210 | 0.03 | 16 | 16.9 | 76 | 16.6 |

| 1490 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 19.7 | 60.8 | 13.3 |

| 5810 | 0.03 | 0.5 | 14.3 | 50.3 | 11.3 |

| 2-76 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 26 | 115 | 25.3 |

| 2183 | 0.06 | >128 | 24.8 | 102 | 22.5 |

| 98-17 | 0.12 | 16 | 28.1 | 72 | 15.8 |

| 98-234 | 0.25 | 32 | 97.5 | 265 | 58 |

| Mean ± SD | 24 ± 17 | ||||

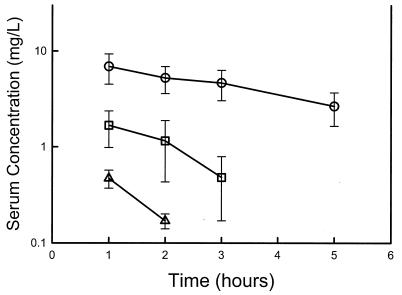

PKs.

The time courses of the serum voriconazole concentration in infected neutropenic mice following the administration of oral doses of 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg are shown in Fig. 1. The peak levels in serum and the AUC increased in a nonlinear fashion with dose escalation. Peak levels ranged from 0.5 ± 0.1 to 6.9 ± 2.4 μg/ml. The elimination half-life ranged from 0.72 to 2.9 h. The AUC, as determined by use of the trapezoidal rule, ranged from 0.72 to 27.2 mg · h/liter with the lowest and the highest doses, respectively. The level of protein binding in mouse serum was 78% at concentrations of 10 and 100 μg/ml. The lower limit of detection limited data analysis with the 10-mg/kg dose to two time points. While it is not possible to accurately predict time course measurements with two points, the available values do provide useful peak level information. In addition, the relationship between the predicted elimination half-life and AUC for this dose level and the higher levels studied provides a useful estimate of the dose dependency of voriconazole kinetics in this model.

FIG. 1.

Serum voriconazole concentrations after administration of oral doses of 10 (▵), 20 (□), and 40 (○) mg/kg in neutropenic infected mice. Each symbol represents the geometric mean ± standard deviation of the levels in the sera of three mice. The elimination half-lives, AUC, and maximum concentration in serum were 2.90 ± 0.12 h, 27.2 ± 12.2 mg · h/liter, and 6.9 ± 2.40 mg/liter, respectively, for the 40-mg/kg dose; 1.14 ± 0.02 h, 3.84 ± 1.70 mg · h/liter, and 1.67 ± 0.69 mg/liter, respectively, for the 20-mg/kg dose; and 0.68 ± 0.04 h, 0.72 ± 0.12 mg · h/liter, and 0.47 ± 0.10 mg/liter, respectively, for the 10-mg/kg dose.

PD parameter determination.

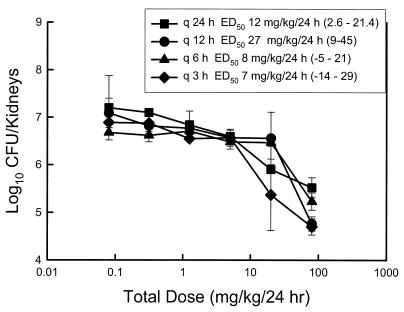

At the start of therapy the kidneys had 3.50 ± 0.18 log10 CFU/kidneys. After 24 h the organisms grew to 3.70 ± 0.23 log10 CFU/kidneys in untreated mice. Drug carryover was not observed in any of the samples. Over the range of voriconazole doses studied there was no killing of organisms compared to the organism burden in the kidneys at the start of therapy. However, compared to the burden at the end of the study period in untreated animals, the maximal organism reductions with the various dosing intervals ranged from 1.68 ± 0.21 to 2.50 ± 0.17 log10 CFU/kidneys. Drug toxicity precluded study of higher dose levels. The dose-response curves for each of the four dosing regimens are shown in Fig. 2. As the dosing interval was shortened, the dose-response curves retained similar shapes, indicating similar efficacies. There was no significant difference among the doses necessary to produce the ED50 (Fig. 2) with each of the dose levels (range, 7.0 ± 11 to 27 ± 10 mg/kg/24 h) (P = 0.39). The results were clearly dependent on the dose level and not on the dosing interval, which suggests that the AUC of exposure best determines the outcome.

FIG. 2.

Relationship between the 24-h total dose and the change in log10 CFU per kidneys over the treatment period for voriconazole administered at different dosing intervals in a neutropenic murine model of disseminated candidiasis caused by C. albicans K-1. q 24 h, q 12 h, q 6 h, and q 3 h, dosing every 24, 12, 6, and 3 h, respectively; the values in parentheses represent 95% confidence intervals.

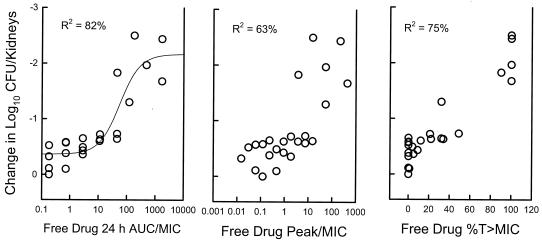

The relationships between microbiologic effect and each of the PD parameters (T > MIC, AUC/MIC ratio, and peak/MIC) are shown in Fig. 3 and are based on the results for free drug. The data regressed with the AUC in relation to the MIC had the strongest relationship, with an R2 of 82%. The relationship between efficacy and both peak/MIC and T > MIC was not as strong (for peak/MIC, R2 = 63%; for T > MIC, R2 = 75%). Consideration of protein binding did not appreciably affect the relationship between outcome and T > MIC (for total drug, R2 for T > MIC = 64%; for free drug, R2 for T > MIC = 75%).

FIG. 3.

Relationship between free drug T > MIC, AUC/MIC ratio, peak/MIC, and the change in log10 CFU per kidneys. Each symbol represents data for two mice.

Correlation of magnitude of PD parameter with efficacy.

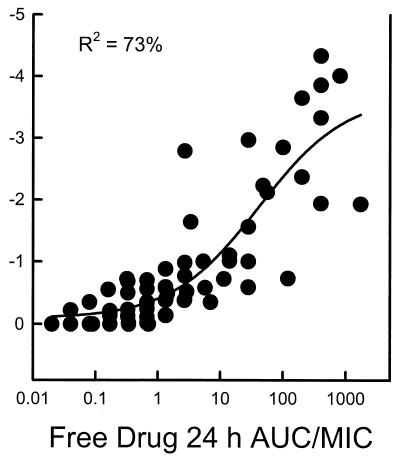

Each of the 10 C. albicans strains grew similarly in the animals. At the start of therapy the kidneys had 3.33 ± 0.18 log10 CFU/kidneys. The range of organism growth for the control animals was 2.11 ± 0.32 to 3.70 ± 0.24 log10 CFU/kidneys. The relationship between the voriconazole free drug 24-h AUC/MIC ratios and efficacy against the 10 strains is displayed in Fig. 4. The relationship among the treatment groups was highly significant (R2 = 73%). The voriconazole dose necessary to achieve the ED50 varied 12-fold (range, 7.9 to 97.5 mg/kg) (Table 1). However, the 24-h AUC/MIC ratios representative of these doses varied only fivefold (total drug AUC/MIC ratio range, 50 to 265; free drug AUC/MIC ratio range, 11 to 58). The difference among these AUC/MIC ratios was not significant (P = 0.45).

FIG. 4.

Relationship between the total and free drug 24-h AUC/MIC ratio and the change in log10 CFU per kidneys (y axis) after 1 day of treatment with voriconazole for 10 C. albicans organisms. Each symbol represents data for two voriconazole-treated mice.

DISCUSSION

Studies with several triazole drugs have shown that treatment outcome is dependent on the total amount of drug (AUC) and not the dosing interval (1, 3, 12). The present analysis examined the outcomes of voriconazole therapy with a total dose range that varied more than 1,000-fold and four dosing intervals. These investigations with voriconazole also demonstrated that treatment outcomes are most dependent on the total amount of drug, or the AUC.

The concordance of PK-PD parameter magnitudes among animal species and in humans has been demonstrated for a variety of antibacterials (4, 6). This should not be surprising, given that PK-PD parameters can correct for differences in PKs among animal species. Furthermore, the receptors for antimicrobials are in the pathogen and are therefore similar in all animals. Very few animal model studies of voriconazole have used mice because of the rapid metabolism of mice and, thus, the shorter elimination half-life in this species (22). However, the use of higher doses and more frequent dose administration and consideration of drug levels as PD parameters in relation to the MICs for the organism allowed us to use a murine model to address a variety of PD questions.

Studies with numerous antimicrobials have also shown that the magnitude of the PK-PD parameter required for efficacy is similar for drugs within the same class, provided that free drug concentrations are considered, and is similar for the treatment of infections caused by organisms with reduced susceptibilities (2, 4). Thus, the results of studies with these experimental models have been shown to be useful for the design of dosing regimens in humans and for the more rational development of in vivo susceptibility breakpoints (7, 13).

In vivo observations with fluconazole, ravuconazole, and posaconazole found that an AUC/MIC ratio in the range of 20 to 25 produced ED50s for both fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant strains. Similar AUC/MIC ratios were also found to be predictive of outcomes in clinical trials with fluconazole (10; Clancy et al., Program Abstr. 36th Annu. Meet. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am.). In the present studies we also chose to use the dose necessary to produce the ED50 to allow comparison of the present data with data for triazoles obtained in other studies.

One major difference between voriconazole and fluconazole is the degree of protein binding (21). Fluconazole has a low degree of protein binding (10%) in all species studied. Because of this low degree of protein binding across animal species, total drug levels were used for PK-PD parameter calculations for fluconazole (1). Each of the newer triazole compounds has a much higher degree of protein binding. Because of this discrepancy, the present studies attempted to determine the impact of protein binding on treatment outcome. In general, it is accepted that only free drug is pharmacologically active (3, 5, 8, 9). This is related to the limited ability of protein-bound drug to diffuse across cellular membranes to reach the drug target. The importance of free drug levels has recently been demonstrated in in vivo investigations of two highly protein bound triazoles, ravuconazole and posaconazole (3; D. Andes, K. Marchillo, and R. Conklin, Abstr. 42nd Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-1265, 2002).

Our protein binding determinations were performed with serum from infected neutropenic mice in an attempt to closely mimic the binding that would occur in treatment studies. The degree of protein binding in this murine infection model is relatively similar to that observed in humans (58% in humans and 78% in this infected mouse model). These studies with organisms for which MICs varied 35-fold suggest that when voriconazole free drug concentrations are considered, treatment efficacy is similar to that observed with fluconazole (Table 1 and Fig. 4). One weakness of these PD predictions is related to the use of linear PK extrapolations (to estimate PKs for drug dosing regimens in which kinetic measurements were not obtained) from actual PK measurements that were nonlinear. However, the ED50s were less than twofold different than the drug doses used in the PK studies.

Animal models of PK-PD have been successfully used to aid in the development of in vitro susceptibility breakpoints for numerous antibacterial drugs. Yet, prediction of the success of treatment of clinical invasive fungal infections on the basis of extrapolations from a homogeneous animal model can be difficult. Often, the host's immune state is more predictive of the outcome than the MIC for the organism or the dose of antifungal used. However, the PK-PD outcomes with fluconazole in animal models have correlated strongly with the outcomes of clinical trials for both mucosal and invasive Candida infections. Furthermore, clinical trials are rarely able to accrue data inclusive of infections due to organisms for which MICs are higher. Thus, the development of breakpoints on the basis of data from clinical trials alone is often difficult and delayed. We believe that the strength of the available data support the use of PK-PD from animal models for the preliminary development of susceptibility breakpoints. If one considers the kinetics of voriconazole in humans, an oral dose of 200 mg twice daily would produce free drug AUCs of 8.4 μg · h/ml (17; voriconazole package insert). If one uses a PD target of a free drug 24-h AUC/MIC ratio of 20, one would predict that these voriconazole dosing regimens could successfully be used for the treatment of infections caused by C. albicans organisms for which MICs are as high as 0.25 μg/ml (free drug AUC/MIC ratio, 20). In vitro surveillance of C. albicans has reported MICs at which 90% of isolates are inhibited of 0.015 μg/ml and MICs at which 90% of all Candida spp. are inhibited of 0.25 μg/ml (15, 16). Although most azole resistance mechanisms do appear to produce a class effect, the differential in vitro potency between fluconazole and voriconazole would likely allow one to successfully treat patients with infections caused by these more resistant pathogens as well.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes, D., and M. L. van Ogtrop. 1999. Characterization and quantitation of the pharmacodynamics of fluconazole in a neutropenic murine model of disseminated candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2116-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andes, D., and W. A. Craig. 1998. In vivo activities of amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate against Streptococcus pneumoniae: application to breakpoint determinations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2375-2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andes, D., K. Marchillo, T. Stamstad, and R. Conklin. 2003. In vivo characterization of the pharmacodynamics of a new triazole, ravuconazole in a murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1193-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig, W. A. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig, W. A., and B. Suh. 1996. Protein binding and the antimicrobial effects: methods for the determination of protein binding. In Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed., p. 367-402. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 6.Craig, W. A., and D. Andes. 1996. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antibiotics in otitis media. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 15:255-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dowell, S. F., J. C. Butler, G. S. Giebink, et al. 1999. Acute otitis media: management and surveillance in an era of pneumococcal resistance—a report from the Drug-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Working Group. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunin, C. M. 1965. The importance of serum protein binding in determining antimicrobial activity and concentration in serum. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 7:168-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunin, C. M., W. A. Craig, M. Kornguth, and R. Monson. 1973. Influence of binding on the pharmacological activity of antibiotics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 226:214-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, S. C., C. P. Fung, J. S. Huang, C. J. Tsai, K. S. Chen, N. L. Chen, L. C. See, and W. B. Shieh. 2000. Clinical correlates of antifungal macrodilution susceptibility test results for non-AIDS patients with severe Candida infections treated with fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2715-2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Ribot, J. L., R. K. McAtee, L. N. Lee, W. R. Kirkpatrick, T. C. White, D. Sanglard, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2932-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louie, A., G. L. Drusano, P. Banerjee, Q. F. Liu, W. Liu, M. Kaw, H. Shayegani, H. Taber, and M. H. Miller. 1998. Pharmacodynamics of fluconazole in a murine model of systemic candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1105-1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing for yeast; approved standard. M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 14.National Research Council Committee on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, and Commission on Life Sciences. 1996. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

- 15.Pfaller, M. A., R. N. Jones, G. V. Doern, A. C. Fluit, J Verhoef, H. S. Sader, S. A. Messer, A. Houston, S. Coffman, and R. J. Hollis. 1999. International surveillance of blood stream infections due to Candida species in the European SENTRY Program: species distribution and antifungal susceptibility including the investigational triazole and echinocandin agents. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, R. J. Hollis, R. N. Jones, and D. J. Diekema. 2002. In vitro activities of ravuconazole and voriconazole compared with those of four approved systemic antifungal agents against 6,970 clinical isolates of Candida spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1723-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purkins, L., N. Wood, P. Ghahramini, K. Greenhalgh, M. J. Allen, and D. Kleinermans. 2002. Pharmacokinetics and safety of voriconazole following intravenous- to oral-dose escalation regimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:2546-2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, J. N. Galgiani, M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, M. Lancaster, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinadli, T. J. Walsh, and A. L. Barry for the NCCLS Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing. 1997. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro and in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers, T. E., and J. N. Galgiani. 1986. Activity of fluconazole (UK 49, 858) and ketoconazole against Candida albicans in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:418-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryan, D. M., B. Hodges, G. R. Spencer, and S. M. Harding. 1982. Simultaneous comparison of three methods for assessing ceftazidime penetration into extravascular fluid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 22:995-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan, D. J., C. A. Hitchcock, and C. M. Sibley. 1999. Current and emerging azole antifungal agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:40-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sugar, A. M., and X. P. Liu. 2001. Efficacy of voriconazole in treatment of murine pulmonary blastomycosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:601-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van't Wout, J., H. Mattie, and R. van Furth. 1989. Comparison of the efficacies of amphotericin B, fluconazole, and itraconazole against systemic Candida albicans infection in normal and neutropenic mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:147-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vogelman, B., S. Gudmundsson, J. Leggett, J. Turnidge, S. Ebert, and W. A. Craig. 1988. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 158:831-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warnock, D. W., E. M. Johnson, and D. A. White. 1999. Antifungal drug measurements, p. 221-233. In D. S. Reeves, R. Wise, J. M. Andrews, L. O. White, and D. Speller (ed.), Clinical antimicrobial assays. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 26.White, T. C., S. Holleman, F. Dy, L. F. Mirels, and D. A. Stevens. 2002. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1704-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]