Abstract

The in vitro virulence properties of 197 temporally and geographically related Campylobacter isolates from chicken broilers and humans were compared. Comparisons of the virulence properties associated with genotypes and biotypes were made. All isolates adhered to, and 63% invaded, INT-407 cells, whereas 13% were cytotoxic for CHO cells. CHO cell-cytotoxic extracts were also cytotoxic for INT-407 cells, but the sensitivity for Vero cells was variable. The proportion of isolates demonstrating a high invasiveness potential (>1,000 CFU ml−1) or Vero cell cytotoxicity was significantly higher for human than for poultry isolates. Invasiveness was associated with Campylobacter jejuni isolates of biotypes 1 and 2, whereas CHO and INT-407 cell cytotoxicity was associated with C. jejuni isolates of biotypes 3 and 4. Cytotoxic isolates were also clustered according to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles.

Campylobacter spp. are recognized as the most common cause of food-borne bacterial gastroenteritis in humans (2). Epidemiological studies revealed that consumption of poultry products is an important risk factor for sporadic cases of human campylobacteriosis (14, 15), and many studies have identified common types of Campylobacter from poultry and humans (5, 26, 28, 29). The extent to which poultry consumption is responsible for human infections is nevertheless not exactly known (12). Asymptomatic infections, watery diarrhea, and dysentery-type illnesses of humans have been reported (36). Campylobacter jejuni strains associated with dysentery-like illness have been shown to be more invasive and cytotoxic than other Campylobacter strains in in vitro assays (22). Adherence to and invasion of host mucosal surfaces were proposed as essential steps in the pathogenesis (11). In addition, many cytotoxic activities have been reported, but their significance in human disease remains unclear (37). Subgrouping Campylobacter strains with respect to their virulence factors would be an important step in understanding the epidemiology and the pathogenesis of the infection. pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) is one of the most powerful techniques for the genotyping of Campylobacter (27). Although the restriction endonuclease SmaI has been widely used for Campylobacter PFGE analysis, KpnI appears to be most suitable for epidemiological studies of Campylobacter (24).

In a previous study, we reported that approximately 40% of chicken broilers and 60% of lots of slaughtered birds in the province of Quebec (Canada) were colonized by Campylobacter. PFGE and biotyping revealed that approximately 20% of human isolates were related to poultry isolates (26). To assess their pathogenic potential and to determine if clonally related isolates have common characteristics, temporally and geographically related Campylobacter isolates from chicken broilers and sporadic cases of human enteritis were compared for their in vitro virulence abilities.

Sampling and identification of Campylobacter isolates.

A total of 197 Campylobacter isolates, 173 from chicken broilers and 24 from sporadic cases of human diarrhea, were used in this study. Campylobacter isolates were cultured during a 1-year sampling (July 1998 to June 1999) as described previously (26). Samples of poultry cecal contents in two abattoirs in the region of St-Hyacinthe, Québec, Canada, which originated from 52 slaughter lots of 33 farms, were obtained. The human fecal samples originated from the only hospital of the area, located in St-Hyacinthe. Fecal samples from all sporadic cases of diarrhea (n = 296) processed for bacteriology at the hospital were also analyzed in our laboratory. Samples were directly inoculated onto charcoal selective medium (CSM), and the plates were incubated at 42°C under microaerobic conditions. All Campylobacter isolates were identified by standard microbiological procedures as previously described (26). C. jejuni accounted for 95.6 and 91.7% of poultry and human isolates, respectively, whereas the remaining isolates were identified as Campylobacter coli.

Adhesion and invasion assays of INT-407 cells.

For in vitro virulence properties, associations were determined by using the Fisher exact test (α = 0.05). Adhesion and invasion assays were performed as described by Grant et al. (7), except that 7.0 × 104 INT-407 cells were seeded into each well of 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) to obtain semiconfluent monolayers after an incubation at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2. Briefly, each well was then inoculated with 5 × 107 CFU of Campylobacter, and the plates were centrifuged. For the adhesion assay, plates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, whereas for the invasion assay they were incubated for 3 h and incubated for another 2 h in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 250 μg of gentamicin ml−1. Adherent and intracellular bacteria were evaluated by plating serial dilutions of the cell lysates on CSM agar plates without selective supplement and by counting the colonies after incubation.

In accordance with the findings of other studies (11, 20), all C. jejuni and C. coli isolates adhered to INT-407 cells. The number of bacteria that adhered ranged from 1.0 × 103 to 1.8 × 106 CFU ml−1, representing 0.001 to 1.8% of the bacterial inoculum, in accordance with results observed in other studies (17, 18, 32). The ability of Campylobacter to invade epithelial cells in vitro is recognized as strain dependent (17). As observed by Lindblom and Kaijser (20), the proportions of poultry and human isolates that showed invasiveness were not statistically different (Pexact = 0.1547), being 63.6 and 58.3%, respectively. Lindblom and Kaijser (20) reported that 40% of human and hen isolates were invasive, whereas Tay et al. (34) reported invasiveness properties for 82% of human isolates. Adhesion to and invasion of epithelial cells by Campylobacter are affected by assay parameters, and considerable variations in in vitro techniques are described in the literature (10, 17, 30). Consequently, the comparison of in vitro adhesion and invasion abilities of Campylobacter isolates among studies is difficult. In the present study, the number of invasive bacteria ranged from 1 × 102 to 5 × 104 CFU ml−1, representing 0.0001 to 0.05% of the bacterial inoculum. Although 21.3% of the isolates showed intracellular numbers >1,000 CFU ml−1, the proportion of human isolates above this level was significantly higher than the proportion of poultry isolates (Pexact = 0.0277) (Table 1). However, a higher number of isolates from humans would be required to confirm this dissimilarity since the discrepancy between the numbers of human and poultry isolates may skew the invasion results in favor of human isolates.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of invasive and cytotoxic Campylobacter isolates among biotypes according to invasion ability for INT-407 cells and cytotoxic activity for CHO cells

| Biotypea | No. (% of the total sample) of isolates that were:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive (intracellular no. >1,000 CFU ml−1)

|

Cytotoxic (polymyxin B extracts)

|

|||

| Human (n = 24) | Poultry (n = 173) | Human (n = 24) | Poultry (n = 173) | |

| CJ-1 | 4 (16.7) | 13 (7.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| CJ-2 | 4 (16.7) | 15 (8.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| CJ-3 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (11.6) |

| CJ-4 | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (0.0) |

| CC-1 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| CC-2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 9 (37.5)b | 33 (19.1) | 5 (20.8)c | 21 (12.1) |

CJ, C. jejuni; CC, C. coli.

Statistically higher than for poultry (Pexact = 0.0277).

Not statistically higher than for poultry (Pexact = 0.1172).

Cytotoxin assay of epithelial cells.

Campylobacter cells were harvested from a 24-h culture on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate incubated at 42°C, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended at an optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of 0.75 in MEM containing 0.15% (wt/vol) polymyxin B sulfate (Sigma). Suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and centrifuged at 2,500 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size disposable filter (Millipore). Toxin assays were carried out in 96-well tissue culture plates (Nunclon). Polymyxin B extracts were added (100 μl) in triplicate, and doubling dilutions were performed with MEM supplemented with 3% FBS. Freshly trypsinized Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells (4 × 105 cells ml−1) suspended in MEM supplemented with 3% FBS were then added (100 μl). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in 5% CO2. Wells were observed at 24-h intervals with an inverted microscope. After 48 h, the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) dye reduction assay was performed as previously described (4) to minimize subjective errors. The cytotoxic titer was the dilution of the well in which cell death (1 − [mean OD of test wells/mean OD of negative-control wells] × 100) was ≥25%. This cutoff value was estimated by doubling the percentage of intraplate variation of CHO cell growth. Titers <1/4 were considered nonspecific. All CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates were also tested with Vero and INT-407 cells by the same assay but with a serum concentration of 5% for INT-407 cells and 1% for Vero cells.

CHO cell cytotoxicity was observed for 26 (13.2%) of the Campylobacter isolates (Table 1). Cytotoxicity was associated with rounded and detached cells. For some isolates, this activity was observed microscopically as soon as 24 h after incubation. Titers varied from 1/16 to 1/128 for 23 of the 26 cytotoxic isolates, whereas they were less than 1/16 for the three others. Campylobacter cytotoxic activities have been classified into those of cytodistending toxin (CDT) and non-CDT toxins (31, 37), but comparison of cytotoxic activities among studies is difficult due to confusion concerning Campylobacter cytotoxins. Distension of cells by CDT can normally be observed after 48 h of incubation (9, 13). CDT activities have been frequently observed when sonication or supernatants of Campylobacter cultures were used (6, 13, 33). Non-CDT activities were observed in the present study. McFarland and Neill (23) also reported only non-CDT activity when CHO cells were added to Campylobacter polymyxin B extracts. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the cytotoxicity observed in the present study was associated with viable Campylobacter cells that may have passed through the 0-45-μm-pore-size filters. If this were the case, however, the viable bacteria would have reduced the MTT, consequently concealing the epithelial cell death caused by the cytotoxicity. Furthermore, no bacterial growth was observed in wells with the inverted microscope.

The proportion of human cytotoxic isolates was much lower than that reported in the literature (37). It is possible that titers considered nonspecific (<1/4) reflected a weak activity of cytotoxicity since non-CDT titers are generally low (31). Moreover, the cytotoxic cutoff value chosen might also contribute to concealing weak cytotoxic activities. Some authors reported more non-CDT cytotoxic activity in human isolates than in animal isolates (1, 19, 32, 33), whereas, as in the present study (Table 1), others reported no difference (20, 25).

All tested CHO cell-cytotoxic extracts were also cytotoxic for INT-407 cells (Table 2). Poultry isolates were generally not toxic for Vero cells or, if so, had weaker titers, whereas four of the five CHO cell cytotoxic human isolates were cytotoxic for Vero cells. A significantly higher proportion of human than of poultry CHO cell-cytotoxic extracts were cytotoxic for Vero cells (Pexact = 0.0372). Other authors reported a weaker reaction on Vero cells than on other cell lines (1, 16, 19) and conflicting results with regard to Vero cell sensitivity (31). Since more than one cytotoxin activity has been previously observed (31) and since the results obtained for the Vero cell assay were variable among CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates, we cannot eliminate the possibility of multiple cytotoxin activities for the tested isolates.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of cytotoxic activities of polymyxin B extracts of human and poultry Campylobacter isolates on different cell lines

| Isolate no. | Genotypea | Biotypeb | Cytotoxic activityc on cell line:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHO | INT-407 | Vero | |||

| 853 | 18 | CJ-3 | 64 | 16 | <4 |

| 881 | 18 | CJ-3 | 16 | 16 | <4 |

| 897 | 18 | CJ-3 | 32 | NTe | NT |

| 2183 | 18 | CJ-3 | 16 | NT | NT |

| 2220 | 18 | CJ-3 | 4 | 8 | <4 |

| 876 | 20 | CJ-3 | 8 | NT | NT |

| 1250 | 27 | CJ-3 | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| 1257 | 27 | CJ-3 | 128 | 16 | 4 |

| 1262 | 27 | CJ-3 | 32 | 32 | <4 |

| 1269 | 27 | CJ-3 | 16 | 16 | <4 |

| 1278 | 27 | CJ-3 | 32 | 16 | 8 |

| 1500 | 31 (U) | CJ-3 | 32 | 16 | <4 |

| 2005 | 41 (U) | CJ-4 | 64 | 32 | 8 |

| 2150 | 44 | CJ-3 | 64 | 32 | <4 |

| 2155 | 44 | CJ-3 | 16 | 16 | <4 |

| 2165 | 44 | CJ-3 | 32 | 8 | <4 |

| 2169 | 44 | CJ-3 | 16 | NT | NT |

| 2178 | 44 | CJ-3 | 32 | 32 | <4 |

| 2188 | 44 | CJ-3 | 64 | 8 | <4 |

| 2194 | 44 | CJ-3 | 32 | 16 | <4 |

| 2199 | 44 | CJ-3 | 16 | 16 | <4 |

| Human-1 | 1 (U) | CJ-1 | 64 | 32 | 16 |

| Human-41 | 5 (U) | CJ-4 | 16 | 16 | <4 |

| Human-142 | 9 | CJ-2 | 64 | 16 | 8 |

| Human-144 | 9 | CJ-2 | 64 | 16 | 4 |

| Human-176 | 50 (U) | CJ-4 | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| 2070d | 42 | CJ-2 | <4 | <4 | <4 |

KpnI profiles. U, unique.

CJ, C. jejuni.

Reciprocal cytotoxicity titers.

Noncytotoxic strain

NT, not tested.

Subgrouping Campylobacter isolates with regard to their in vitro virulence abilities.

The isolates were biotyped according to the scheme of Lior (21). PFGE was done as described previously using the KpnI enzyme (26). Genetic relationships of strains were also established as described previously (26, 35). In the dendrogram, genotypes were delineated with a 90% similarity cutoff level. The 197 Campylobacter isolates were distributed in 57 different KpnI genotypes. Only poultry isolates (n = 155) were clustered in 37 genotypes. Both human (n = 5) and poultry isolates (n = 18) were found in 4 genotypes, and the remaining human isolates (n = 19) were clustered in 16 genotypes.

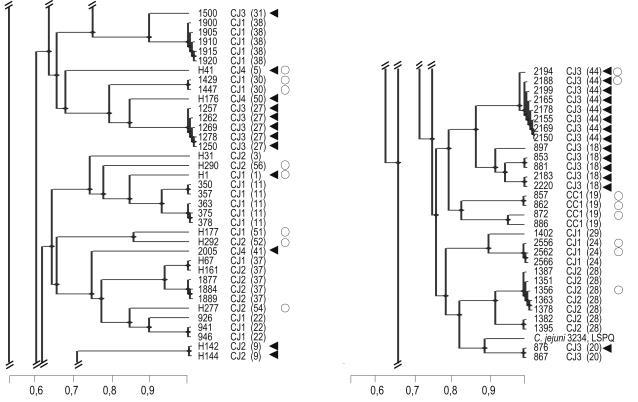

Nearly all invasive isolates with an intracellular numbers >1,000 CFU ml−1 belonged to biotypes 1 and 2 of C. jejuni, whereas CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates were associated with C. jejuni biotypes 3 and 4 (Table 1). The latter association has not been previously reported except for the observation of a higher cytotoxic activity for a polymyxin B extract of a C. jejuni biotype 4 isolate (8). Unlike Carvalho et al. (3), who identified a randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting cluster comprising the more-invasive isolates, we observed that invasive isolates were distributed throughout the PFGE dendrogram. On the other hand, 18 of the 21 CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates from poultry were clustered in three genotypes (Table 2) and in two clusters in the dendrogram (Fig. 1). These results suggest that these cytotoxic isolates represent a subgroup of Campylobacter sharing particular characteristics. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that the clusters are due to a geographical relationship since the exact locations of the farms and patients are not known.

FIG. 1.

Representative portions of the PFGE KpnI dendrogram. The scale measured similarity values. Levels of similarity were calculated with the Dice coefficient, and the unweighted pair group method using arithmetical averages was used for cluster analysis. Human Campylobacter isolate numbers are preceded by H, and poultry isolates consist of numbers only. Each isolate number is followed by the biotype (CJ, C. jejuni; CC, C. coli) and, in parentheses, the PFGE KpnI genotype. Circles, isolates with an intracellular numbers >1,000 CFU ml−1; triangles, CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates. Genotypes were delineated with a 90% similarity cutoff level.

Higher invasiveness has been reported among noncytotoxic isolates (20). In this study, CHO cell-cytotoxic isolates generally had an intracellular numbers of 0 to 1,000 CFU ml−1 except for two C. jejuni biotype 3 cytotoxic isolates from poultry and two C. jejuni biotype 1 cytotoxic isolates from humans that showed intracellular numbers >1,000 CFU ml−1. Since invasive isolates belonged to different biotypes than cytotoxic isolates, it is possible that distinct Campylobacter populations carry these two putative virulence factors. On the other hand, the cytotoxic activity might affect the invasion process and the ability to measure invasion.

Finally, isolates clustered in a particular KpnI genotype had similar invasion abilities, with few exceptions, and had the same CHO cell cytotoxicity status (cytotoxic or not), except for the poultry cytotoxic isolate 876, which clustered with the noncytotoxic isolate 867 (Fig. 1). This homogeneity of in vitro virulence properties within a particular KpnI genotype suggests that the phenotype may be stable for isolates clustered in a particular genotype. Surprisingly, all isolates included in the four genotypes comprising poultry and human cases were not invasive or were weakly invasive (≤1,000 CFU ml−1) and not cytotoxic.

Overall, the data presented in this study revealed an association of in vitro virulence properties with biotype, genotype, and host of origin. Invasive isolates were associated with biotypes 1 or 2 of C. jejuni, whereas CHO cell- and INT-407 cell-cytotoxic isolates were associated with biotypes 3 and 4 of C. jejuni and were clustered with PFGE groups. Human isolates were more invasive and Vero cell cytotoxic than poultry isolates. These data also suggest that clonally related isolates have common in vitro virulence characteristics and that subgroups of Campylobacter, with respect to potential virulence abilities, exist. Further work is needed to determine if cytotoxic C. jejuni isolates associated with biotypes 3 and 4 are widely distributed among C. jejuni strains and to characterize the subgroup of biotype 3 and 4 C. jejuni cytotoxic isolates.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Health Canada authorities at the Food and Veterinary Hygiene Laboratory of Saint-Hyacinthe for their collaboration and access to their facilities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhtar, S. Q., and F. Huq. 1989. Effect of Campylobacter jejuni extracts and culture supernatants on cell culture. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 92:80-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atabay, H. I., and J. E. L. Corry. 1997. The prevalence of campylobacters and arcobacters in broiler chickens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 83:619-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho, A. C. T., G. M. Ruiz-Palacios, P. Ramos-Cervantes, L.-E. Cervantes, X. Jiang, and L. K. Pickering. 2001. Molecular characterization of invasive and noninvasive Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1353-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coote, J. G., and T. Arain. 1996. A rapid, colourimetric assay for cytotoxin activity in Campylobacter jejuni. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 13:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duim, B., T. M. Wassenaar, A. Rigter, and J. Wagenaar. 1999. High-resolution genotyping of Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry and humans with amplified fragment length polymorphism fingerprinting. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2369-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyigor, A., K. A. Dawson, B. E. Langlois, and C. L. Pickett. 1999. Detection of cytolethal distending toxin activity and cdt genes in Campylobacter spp. isolated from chicken carcasses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1501-1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant, C. C. R., M. E. Konkel, W. Cieplak, Jr., and L. S. Tompkins. 1993. Role of flagella in adherence, internalization, and translocation of Campylobacter jejuni in nonpolarized and polarized epithelial cell cultures. Infect. Immun. 61:1764-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerrant, R. L., C. A. Wanke, R. A. Pennie, L. J. Barrett, A. A. Lima, and A. D. O'Brien. 1987. Production of a unique cytotoxin by Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 55:2526-2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hänel, I., F. Schulze, H. Hotzel, and E. Schubert. 1998. Detection and characterization of two cytotoxins produced by Campylobacter jejuni strains. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 288:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, L., and D. J. Kopecko. 1999. Campylobacter jejuni 81-176 associates with microtubules and dynein during invasion of human intestinal cells. Infect. Immun. 67:4171-4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu, L., and D. J. Kopecko. 2000. Interactions of Campylobacter with eukaryotic cells: gut luminal colonization and mucosal invasion mechanisms, p. 191-215. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Jacobs-Reitsma, W. 2000. Campylobacter in food supply, p. 467-481. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Johnson, W. M., and H. Lior. 1988. A new heat-labile cytolethal distending toxin (CLDT) produced by Campylobacter spp. Microb. Pathog. 4:115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapperud, G., E. Skjerve, L. Vik, K. Hauge, A. Lysaker, I. Aalmen, S. M. Ostroff, and M. Potter. 1993. Epidemiological investigation of risk factors for Campylobacter colonization in Norvegian broiler flocks. Epidemiol. Infect. 111:245-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ketley, J. M. 1997. Pathogenesis of enteric infection by Campylobacter. Microbiology 143:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klipstein, F. A., R. F. Engert, H. Short, and E. A. Schenk. 1985. Pathogenic properties of Campylobacter jejuni: assay and correlation with clinical manifestations. Infect. Immun. 50:43-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konkel, M. E., M. D. Corwin, L. A. Joens, and W. Cieplak. 1992. Factors that influence the interaction of Campylobacter jejuni with cultured mammalian cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 37:30-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konkel, M. E., L. A. Joens, and P. F. Mixter. 2000. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter jejuni virulence determinants, p. 217-240. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Lee, A., S. C. Smith, and P. J. Coloe. 2000. Detection of a novel Campylobacter cytotoxin. J. Appl. Microbiol. 89:719-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindblom, G.-B., and B. Kaijser. 1995. In vitro studies of Campylobacter jejuni/coli strains from hens and humans regarding adherence, invasiveness, and toxigenicity. Avian Dis. 39:718-722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lior, H. 1984. New extended biotyping scheme for Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, and “Campylobacter laridis.” J. Clin. Microbiol. 20:636-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahajan, S., and F. G. Rodgers. 1990. Isolation, characterization, and host-cell-binding properties of a cytotoxin from Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1314-1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFarland, B. A., and S. D. Neill. 1992. Profiles of toxin production by thermophilic Campylobacter of animal origin. Vet. Microbiol. 30:257-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michaud, S., S. Ménard, C. Gaudreau, and R. D. Arbeit. 2001. Comparison of SmaI-defined genotypes of Campylobacter jejuni examined by KpnI: a population-based study. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:1075-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misawa, N., T. Ohnishi, K. Itoh, and E. Takahashi. 1995. Cytotoxin detection in Campylobacter jejuni strains of human and animal origin with three tissue culture assay systems. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:354-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadeau, É., S. Messier, and S. Quessy. 2002. Prevalence and comparison of genetic profiles of Campylobacter strains isolated from poultry and sporadic cases of campylobacteriosis in humans. J. Food Prot. 65:73-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell, D. G., J. A. Frost, F. B. Duim, J. A. Wagenaar, R. H. Madden, J. van der Plas, and S. L. W. On. 2000. New developments in the subtyping of Campylobacter species, p. 27-44. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Nielsen, E. M., J. Engberg, and M. Madsen. 1997. Distribution of serotypes of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli from Danish patients, poultry, cattle and swine. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 19:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.On, S. L. W., E. M. Nielsen, J. Engberg, and M. Madsen. 1998. Validity of SmaI-defined genotypes of Campylobacter jejuni examined by SalI, KpnI, and BamHI polymorphisms: evidence of identical clones infecting humans, poultry, and cattle. Epidemiol. Infect. 120:231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pei, Z., C. Burucoa, B. Grignon, S. Baqar, X.-Z. Huang, D. J. Kopecko, A. L. Bourgeois, J.-L. Fauchere, and M. J. Blaser. 1998. Mutation in the peb1A locus of Campylobacter jejuni reduces interactions with epithelial cells and intestinal colonization of mice. Infect. Immun. 66:938-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickett, C. L. 2000. Campylobacter toxins and their role in pathogenesis, p. 179-190. In I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (ed.), Campylobacter, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 32.Prasad, K. N., T. N. Dhole, and A. Ayyagari. 1996. Adherence, invasion and cytotoxin assay of Campylobacter jejuni in HeLa and Hep-2 cells. J. Diarrhoeal Dis. Res. 14:255-259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulze, F., I. Hanel, and E. Borrmann. 1998. Formation of cytotoxins by enteric Campylobacter in humans and animals. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 288:225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tay, S. T., S. Devi, S. Puthucheary, and I. Kautner. 1996. In vitro demonstration of the invasive ability of Campylobacters. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 283:306-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallis, M. R. 1994. The pathogenesis of Campylobacter jejuni. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 51:57-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wassenaar, T. M. 1997. Toxin production by Campylobacter spp. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:466-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]