Abstract

Transposon mutagenesis with the Enterococcus faecalis transposon Tn917 is a genetic approach frequently used to identify genes related with specific phenotypes in gram-positive bacteria. We established an arbitrary PCR for the rapid and easy identification of Tn917 insertion sites in Staphylococcus epidermidis with six independent, well-characterized biofilm-negative Tn917 transposon mutants, which were clustered in the icaADBC gene locus or harbor Tn917 in the regulatory gene rsbU. For all six of these mutants, short chromosomal DNA fragments flanking both transposon ends could be amplified. All fragments were sufficient to correctly identify the Tn917 insertion sites in the published S. epidermidis genomes. By using this technique, the Tn917 insertion sites of three not-yet-characterized biofilm-negative or nonmucoid mutants were identified. In the biofilm-negative and nonmucoid mutant M12, Tn917 is inserted into a gene homologous to the regulatory gene purR of Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. The Tn917 insertions of the nonmucoid but biofilm-positive mutants M16 and M20 are located in genes homologous to components of the phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) of B. subtilis, S. aureus, and Staphylococcus carnosus, indicating an influence of the PTS on the mucoid phenotype in S. epidermidis.

The Enterococcus faecalis transposon Tn917 is a well-characterized tool in genetic manipulation of gram-positive bacteria. In a variety of bacteria, such as Bacillus species, Streptococcus species, enterococci, Listeria monocytogenes, and staphylococci, Tn917 was used to identify genes related to characteristic phenotypes or metabolic pathways (15, 25, 36, 46, 49, 51, 55). In the era before the sequencing of complete bacterial genomes, transposon insertion sites were analyzed by cloning or inverted PCR requiring the effort of chromosomal mapping. In recent years several bacterial genomes could be deciphered, including major gram-positive pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, L. monocytogenes, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, as well as the gram-positive model organism B. subtilis. Therefore, in the postgenomic era short nucleotide or protein sequences are sufficient for the identification of genes in the respective genomes.

In S. epidermidis biofilm formation is the major pathogenic factor in foreign body-associated infections and leads to increased resistance against antibiotics (14, 22, 26). Biofilm-forming S. epidermidis strains display a mucoid phenotype with large humid colonies under certain culture conditions, as is observed for other bacteria expressing exopolysaccharides. Tn917 mutagenesis identified several genes involved in biofilm formation of S. epidermidis. Five of these mutants are clustered with different orientations of Tn917 in the icaADBC gene locus (29, 30), which is coding for four synthetic enzymes of the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) (13, 16). PIA is essential for cell accumulation during biofilm formation in S. epidermidis (28). PIA and biofilm formation as a virulence factor in S. epidermidis could be demonstrated by different animal models (43-45). In the sixth biofilm-negative and nonmucoid mutant, the Tn917 insertion is located in the first gene rsbU of the σB operon coding for a positive regulator of the alternative sigma factor σB (19). The lack of icaADBC transcription (30) in this mutant indicates a regulatory influence of σB on biofilm formation in S. epidermidis. In addition, transduction of this mutation in a methicillin-resistant genetic background leads to reduced susceptibility against oxacillin (31), which is, like biofilm formation, associated with invasive S. epidermidis strains (12). The regulation of biofilm formation by σB was confirmed recently by allelic gene replacement (J. K.-M. Knobloch et al., unpublished data). Indeed, biofilm formation of S. epidermidis is induced by a variety of environmental stress factors, including antibiotics and disinfectants (9, 11, 20, 39, 41, 42). However, at the moment it is still unknown which of these stress factors lead to induction of biofilm formation by activation of σB. Recently, the icaADBC gene locus was also described in S. aureus (8, 9, 33), and the σB dependence of biofilm formation in this staphylococcal species could be demonstrated (40). However, the regulation of biofilm formation seems to be quite different in these two staphylococcal species (21), and the specific differences should be further characterized.

Apparently, screening of S. epidermidis Tn917 mutants identifies gene loci of interest for virulence-associated phenotypes. To rapidly identify Tn917 insertions, we established in the present study an arbitrary PCR technique for rapid and easy identification of Tn917 insertion sites by investigation of these six well-characterized independent biofilm-negative and nonmucoid Tn917 mutants of S. epidermidis 1457 (19, 30). In addition, by using the newly established arbitrary PCR method, the Tn917 insertion sites of the biofilm-negative and nonmucoid mutant M12 (30) and two newly isolated nonmucoid but biofilm-positive mutants M16 and M20 were identified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and isolation of chromosomal DNA.

The bacterial strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. For the detection of biofilm formation, S. epidermidis cells were grown in 96-well tissue culture plates (NunclonDelta; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) or in Lab-Tek Chambered Coverglass cell culture system (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, Ill.) in Trypticase soy broth (TSBBBL; Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.) at 37°C. Biofilm formation was quantified after staining with gentian violet by a BEPII ELISA reader (Behring), as described recently (27). For the detection of a mucoid phenotype, cells were grown on purple agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.4% N-acetylglucosamine (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). To investigate phenotypes on congo red agar (CRA) cells were grown on TSBBBL supplemented with 1% glucose and 1% agar (Becton Dickinson), 0.08% Congo red (CRATSB; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) supplemented with 3.6% sucrose, 1% agar, and 0.08% Congo red (CRABHI) as described recently (21). Isolation of chromosomal DNA of S. epidermidis was performed as described previously (27). Erythromycin was used at a concentration of 150 μg/ml for selection of Tn917 mutants.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain | Comment(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1457 | Isolate from infected central venous catheter harboring cryptic plasmid p1457 | 32, 35 |

| 1457c/pTV1ts | 1457 cured of a cryptic plasmid and containing the temperature-sensitive plasmid pTV1ts harboring transposon Tn917 | 35 |

| 1457-M10 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class I) | 29 |

| 1457-M11 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class I) | 29 |

| M12 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class II) | 30 |

| M15 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class III) | 19, 30 |

| M16 | Isogenic biofilm-positive, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c | This study |

| M20 | Isogenic biofilm-positive, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c | This study |

| M21 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class I) | 30 |

| M22 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class I) | 30 |

| M24 | Isogenic biofilm-negative, nonmucoid Tn917 mutant of S. epidermidis 1457c (class I) | 30 |

Transposon mutagenesis and phage transduction.

Transposon mutagenesis was performed with the temperature-sensitive plasmid pTV1ts containing transposon Tn917 as described previously (27). S. epidermidis 1457c/pTV1ts was grown under nonpermissive temperature for pTV1ts under erythromycin selection, and the resulting mutants were screened for a biofilm-negative and/or nonmucoid phenotype. Phage transduction of Tn917 insertions into wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 were performed with phage 71, kindly provided by V. T. Rosdahl, Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen, Denmark, as described previously (27).

Arbitrary primed PCR and nucleotide sequence analysis.

Amplification of short DNA-fragments was performed by using the DyNazyme DNA polymerase kit (Finzyme, Espoo, Finland) as described by the manufacturer. Oligonucleotides specific for the 5′ end (917-5.1, 917-5.2, and 917-5.3; Table 2) and the 3 end of Tn917 (917-3.1, 917-3.2, and 917-3.3; Table 2), as well as the arbitrary primers (STAPHarb1, STAPHarb2, and arb3; Table 2), were synthesized by MWG Biotech (Munich, Germany). All PCRs were performed in a Primus 96 Thermocycler (MWG Biotech) without a mineral oil overlay.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used as primers

| Primer | Localization (bp)a | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 917-5.1 | 124-103 | 5′-ATC GAT ACA AAT TCC TCG TAG G-3′ |

| 917-5.2 | 274-255 | 5′-AAC CGT TAC CTG TTT GTG CC-3′ |

| 917-5.3 | 353-333 | 5′-CCA ATC ACT CTC GGA CAA TAC-3′ |

| 917-3.1 | 5298-5318 | 5′-TTT AGT GGG AAT TTG TAC CCC-3′ |

| 917-3.2 | 5194-5215 | 5′-GGG AGC ATA TCA CTT TTC TTG G-3′ |

| 917-3.3 | 5102-5122 | 5′-GAA CGC CGT CTA CTT ACA AGC-3′ |

| STAPHarb1 | 5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT CAN NNN NNN NNN GAT AT-3′ | |

| STAPHarb2 | 5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT CAN NNN NNN NNN GAT CA-3′ | |

| arb3 | 5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT CA-3′ |

Localization in the published nucleotide sequence on Tn917 (accession number M11180).

The PCR of the first round was performed in a final volume of 50 μl. An arbitrary primer (STAPHarb1 or STAPHarb2; 200 pmol/reaction) was paired with one of the proximal Tn917 primers (homologous to the external nested-PCR primers [917-5.3, 917-5.2, 917-3.3, or 917-3.2]; 10 pmol/reaction). Portions (1 μl) of the chromosomal DNA preparations were used as templates, and PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min; six cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 30°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min; and finally 72°C for 5 min. Samples were then kept at 4°C.

The second round of PCR was performed in a final volume of 100 μl with 5 μl of the PCR of round 1 as a template. Primer arb3 (20 pmol/reaction) was paired with one of the respective distal Tn917 primers (homologuous to internal nested PCR primers [917-5.2, 917-5.1, 917-3.2, or 917-3.1]; 20 pmol/reaction), and PCR was performed under the following conditions: 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 5 min. The samples were then kept at 4°C. The results of this PCR was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, and PCRs containing at least one distinct visible fragment were used for further characterization.

Nucleotide sequence analysis was performed by using the second PCR directly with the respective Tn917 internal primers on an ABI Prism 310 sequencer with capillary electrophoresis using the ABI Prism dGTP BigDye terminator ready reaction kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.), with 5 to 10 μl of the PCR as a template. Nucleotide sequences were analyzed subsequently with vector NTI suite II software. For identification of the Tn917 insertion sites, a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) search with the sequence representing the chromosomal DNA of the amplified fragments was performed in the unfinished genome database for S. epidermidis RP62A at The Institute of Genomic Research (TIGR) homepage (http://www.tigr.org) and by using a standard nucleotide-nucleotide BLAST (blastn) search (1) in the recently annotated S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 genome (accession number NC_004461).

RESULTS

Evaluation of the arbitrary PCR.

To establish a site-specific arbitrary PCR for the characterization of Tn917 insertions in S. epidermidis, we generated six Tn917-specific primers homologuous to the 5′- and 3′-end of transposon Tn917. Two additional arbitrary primers, including a conserved 5′ end of 20 bases (37), 10 random bases, and a specific 3′ end of five bases adapted to the GC content of about 30% in staphylococci, were generated (Table 2). To evaluate the functionality of the arbitrary PCR the Tn917 insertion sites of six well-characterized biofilm-negative mutants (Table 1) of the biofilm-positive wild-type strain S. epidermidis 1457 were characterized with the arbitrary PCR. In the first round of PCR, a smear of amplified fragments could be detected for all of the six investigated mutants and primer combinations by gel electrophoresis (data not shown). To exclude nonspecific pairing of the Tn917 primers due to the low annealing temperatures in the first round of PCR, we used in the second round the respective distally located Tn917-specific primers. Despite the positive reaction for all primer pairs in the first round in the second, specific PCR round fragments containing Tn917 flanking chromosomal DNA could not be amplified with all primer pairs (Table 3). However, with the respective Tn917-specific distal primers 917-5.1, 917-5.2, and 917-3.2 fragments containing Tn917, flanking chromosomal DNA could be amplified by the arbitrary PCR for all of the six investigated mutants (Table 3), whereas with primer 917-3.1 no sufficiently visible fragments could be obtained by arbitrary PCR. However, in a standard PCR assay this primer was fully functional (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Functionality of arbitrary PCR in different Tn917 mutants

| Mutant | Functionalitya of PCR with first arbitrary primer:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAPHarb1 and first/second Tn917 primers:

|

STAPHarb2 and first/second Tn917 primers:

|

|||||||

| 917-5.3/917-5.2 | 917-5.3/917-5.1 | 917-5.2/917-5.1 | 917-3.3/917-3.2 | 917-5.3/917-5.2 | 917-5.3/917-5.1 | 917-5.2/917-5.1 | 917-3.3/917-3.2 | |

| M10 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| M11 | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| M12 | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| M15 | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| M16 | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| M20 | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| M21 | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| M22 | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| M24 | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+, Arbitrary PCR fragments containing Tn917 flanking chromosomal DNA.

The Tn917 insertion sites were identified from the resulting sequences of arbitrary PCR fragments by analysis with the BLAST tool of the unfinished S. epidermidis RP62A genome at TIGR's homepage (www.tigr.org). All Tn917 insertions of the yet-characterized mutants could be identified correctly. Thus, the typical 5-bp duplication of Tn917 insertions could be identified in mutants M21, M22, and M24 (Table 4), whereas only the 5′ end of Tn917 flanking regions could be cloned for the characterization of these mutants (30). All arbitrary PCRs were performed twice, and similar results were obtained in both analyses (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Nucleotide sequences flanking Tn917 insertions of S. epidermidis transposon mutants

| Mutant | Gene inactivated | Tn917 orientationa | Insertion site sequence (position)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| M10 | icaA | + | TAT GTT ATT (929) Tn917TTA TTT ATC |

| M11 | icaA | + | TTT ATT AAA (86) Tn917TTA AAG AAA |

| M21 | icaC | + | TTT ATA TAT (1001) Tn917TAT ATT CAG |

| M22 | icaC | + | TTT ATT TTC (154) Tn917TTT TCG GCA |

| M24 | icaA | − | GTC AAT AGA (331) Tn917ATA GAG GTA |

| M15 | rsbU | + | TCA CAA AAA (19) Tn917AAA AAG TTA |

| M12 | NDc | − | TTT AAA GTG (792) Tn917AAG TGG AAC |

| M16 | ND | − | GGT TGG TAT (110) Tn917GGT ATG ACA |

| M20 | ND | − | CGG TTT AAA (587) Tn917TTA AAT GCA |

Orientation of the erm gene of Tn917 with respect to the direction of the inactivated open reading frame.

The Tn917 flanking chromosomal region is displayed in the direction of the inactivated open reading frame. The typical 5-bp duplications of the Tn917 insertion are indicated in boldface. The insertion sites relative to the start point of the respective open reading frame are indicated in parentheses.

ND, not determined.

Identification of the Tn917 insertion in mutant M12.

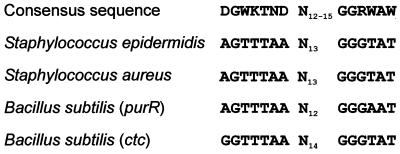

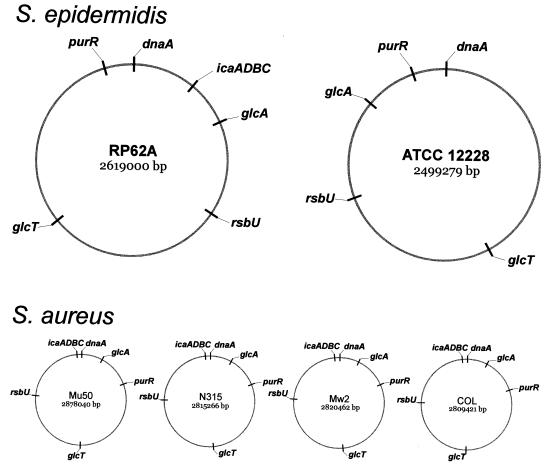

The mutant M12 is characterized by a nonmucoid, biofilm- and hemagglutination-negative phenotype compared to its wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 (30). By using the arbitrary PCR technique, a 5′ Tn917 flanking chromosomal DNA fragment of the Tn917 insertion site could be amplified, whereas for the 3′ site no fragment containing flanking chromosomal DNA was obtained. However, the 5′ Tn917 flanking fragment was sufficient for the identification of the Tn917 insertion site by a BLAST search in S. epidermidis RP62A, as well as in the recently annotated genome of the icaADBC-negative S. epidermidis ATCC 12228. The correct identification of the Tn917 insertion was confirmed by PCR with newly generated primers specific for the identified Tn917 flanking chromosomal regions (data not shown) and the typical 5-bp duplication of Tn917 insertions could thereby be characterized (Table 4). The insertion site of Tn917 in this mutant is located at position 792 of an 825-bp open reading frame (orf2) with high homology to the purR gene of Bacillus subtilis, Lactococcus lactis, and S. aureus. Thus, the highest homology of the S. epidermidis purR homologue was observed with S. aureus with respect of the nucleotide and the putative amino acid sequence (data not shown). Interestingly, the Tn917 insertion site in purR is proceeded by a region (bp 662 to 688 of purR) homologous to the consensus sequence of σB promoters in B. subtilis (38). This DNA motif is highly conserved between the purR genes of S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and B. subtilis (Fig. 1). In the published sequences of S. aureus, homologous genes could be identified in all annotated genomes (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the conserved σB promoter motif within the purR genes of S. epidermidis, S. aureus, and B. subtilis with the consensus sequence (38) and the ctc promoter of B. subtilis, a well-characterized σB-dependent promoter (38).

FIG. 2.

Chromosomal map of the S. epidermidis glcA, glcT, icaADBC, purR, and rsbU genes and their respective homologues in S. aureus. The origin of replication is marked by the gene dnaA. Except for purR, the genes involved in biofilm formation of S. epidermidis are rearranged between the icaADBC-positive and -negative strains, whereas in S. aureus the location of these genes are conserved in four independent strains.

Consensus search for PurBox sequences.

The PurR regulator homologues in B. subtilis and L. lactis regulate transcription of depending genes by binding to specific DNA regions, referred to as PurBoxes (17, 52), which are located in a palindromic way pairwise upstream of regulated genes in B. subtilis (47). Using the consensus sequence for PurBox sequences in B. subtilis and L. lactis, AWWWCCGAACWWT (17), no potential PurR regulatory sequences could be identified in the icaADBC operon by a consensus search with a tolerance of up to two mismatches in the low-importance weight bases or one mismatch of the high-importance weight bases of the consensus sequence (47). In addition, the negative regulator icaR (6, 7) of the icaADBC operon is not preceded by a PurR regulatory sequence.

Generation and characterization of nonmucoid Tn917 mutants.

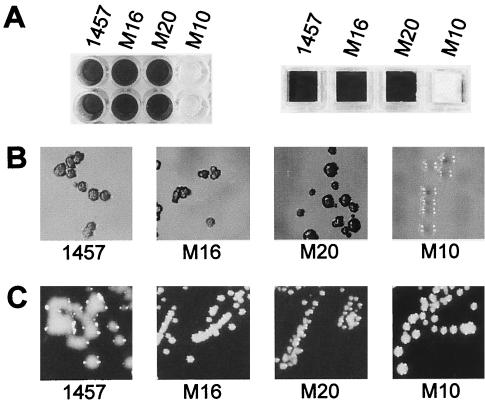

Biofilm-negative mutants of the strongly biofilm-positive and mucoid S. epidermidis 1457 displayed a nonmucoid phenotype on purple agar supplemented with 0.5% N-acetylglucosamine (PurpleGlcNAc). However, the connection between biofilm formation and a mucoid phenotype is unclear at present. Therefore, we carried out transposon mutagenesis, and nonmucoid mutants were further characterized with respect to their ability to establish biofilms. Two mutants M16 and M20 were identified displaying a nonmucoid phenotype on PurpleGlcNAc compared to the wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 (Fig. 3B), whereas phenotypes on Congo red agar (Fig. 3C) and biofilm formation (Fig. 3A) were comparable between the wild type and mutants. The genetic linkage of phenotype and Tn917 insertion of these isogenic mutants was demonstrated by phage transduction of the Tn917 insertions into S. epidermidis 1457. The resulting transductants displayed a phenotype identical to that of the primary mutants (data not shown). The Tn917 insertion sites were subsequently characterized by the arbitrary PCR method, and 5′ and 3′ Tn917 flanking chromosomal DNA fragments could be amplified for M16 and M20 and the typical 5-bp duplication of Tn917 insertions could be identified by a BLAST search in S. epidermidis RP62A, as well as in S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 (Table 4). The correct identification of the Tn917 insertion was confirmed by PCR by using newly generated primers specific for the identified Tn917 flanking chromosomal regions (data not shown). In both mutants the Tn917 insertion was located in open reading frames homologous to genes related to the phosphoenolpyruvate-sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) of B. subtilis, S. carnosus, and S. aureus.

FIG. 3.

Phenotypes of different S. epidermidis mutants. (A) Biofilm formation on polystyrene (left) and glass (right) surfaces. Biofilm formation of the mutants M16 and M20 is comparable to that of wild-type S. epidermidis 1457, whereas the control mutant M10 displays a biofilm-negative phenotype. (B) Phenotypes on Congo red agar (CRABHI). Mutants M16 and M20, as well as the wild-type S. epidermidis 1457, displayed a dry crystalline morphology of black colonies, whereas the red colonies of mutant M10 display a smooth surface. Similar results were obtained on CRATSB (data not shown). (C) Phenotypes on PurpleGlcNAc. The wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 displays a mucoid phenotype, whereas the biofilm-positive Tn917 mutants M16 and M20, as well as the biofilm-negative mutant M10, displayed a mucoid-negative phenotype on this agar.

The Tn917 insertion of mutant M16 was localized at position 110 of an 846-bp open reading frame homologous to the gene of the rho-independent antiterminator GlcT of the B. subtilis and S. carnosus PTS (18, 50) and a respective homologue of S. aureus N315 (accession no. AP003133). Homologous genes could also be identified in all annotated S. aureus genomes (Fig. 2). Thus, the highest homology of the S. epidermidis glcT homologue was observed compared to the respective gene in S. aureus (Fig. 2). However, the homology to the respective glcT gene and the GlcT protein of S. carnosus is similar, and all staphylococcal homologues displayed only a moderate homology to the respective B. subtilis genes and proteins (data not shown).

The Tn917 insertion of mutant M20 was localized at position 587 of a 2,025-bp open reading frame homologous to EII proteins of the PTS in B. subtilis and S. carnosus (4, 5, 54) and a respective homologue of S. aureus N315 (accession no. AP003129). Homologous genes could also be identified in all annotated S. aureus genomes (data not shown). The homology of the respective putative gene products of S. epidermidis and S. aureus to the EII protein GlcA of S. carnosus, which is a glucose-specific component of the PTS, is strikingly high (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Several genomes of S. aureus are published, and two complete genome sequences of S. epidermidis are available. The genome of the nonpathogenic S. epidermidis ATCC 12228 was annotated recently, and the genome of the pathogenic S. epidermidis isolate RP62A is available from TIGR. In addition, the complete genomes of S. carnosus and S. haemolyticus will be available in the near future. Therefore, in the postgenomic era, small chromosomal fragments are sufficient to identify regions or genes of interest in the published staphylococcal genomes. The E. faecalis transposon Tn917 is a well-characterized tool in genetic manipulation of gram-positive bacteria for identifying genes related to characteristic phenotypes or metabolic pathways. In the present study, we established a site-specific arbitrary PCR for the rapid and easy identification of Tn917 insertion sites in S. epidermidis. As a control of functionality of this method, we used six independent and well-characterized biofilm-negative Tn917 mutants of S. epidermidis 1457. For all six of these mutants, short 5′ and 3′ flanking chromosomal DNA fragments could be amplified by the arbitrary PCR. A set of different primer combinations were necessary to amplify fragments sufficient for a correct identification in all mutants. By using the BLAST tool to search TIGR's database of the unfinished S. epidermidis genome, all insertion sites could be correctly identified. For all mutants, the typical 5-bp duplication at the Tn917 insertion site could be detected, completing the data for mutants for which only the 5′ Tn917 flanking chromosomal region could be identified by cloning (30). These results were reproducible and confirm the functionality of this arbitrary PCR method for identifying Tn917 insertion sites in the genome of the used S. epidermidis 1457.

Comparison of the three annotated S. aureus genomes revealed that a large number of genes are only present in one of the three strains (2, 23). Therefore, it it is possible that additional S. epidermidis-specific genes are missing in the RP62A and ATCC 12228 genomes, and the genome of additional clinical S. epidermidis isolates should be characterized to complete our knowledge of S. epidermidis variability and to optimize our understanding of biofilm formation and the pathogenesis of foreign body-related infections.

Using this arbitrary PCR technique, we identified the Tn917 insertion site of the biofilm-negative mutant M12 of wild-type strain S. epidermidis 1457. M12 harbors the Tn917 insertion in a homologue to the purR genes of S. aureus, B. subtilis, and L. lactis. In B. subtilis purR encodes a negative regulator of purine synthesis (52, 53), whereas in L. lactis the regulator PurR has a positive regulatory effect on purine synthesis (17). In B. subtilis a variety of other metabolic genes and operons are regulated by PurR (47). The direct regulation of the icaADBC operon by PurR is unlikely due to a missing putative PurR-binding site. In addition, the gene coding for the negative regulator IcaR (6, 7) of the icaADBC operon is not preceded by a PurR-binding site. Therefore, it is could be speculated that purine synthesis plays a crucial role in biofilm formation. However, the Tn917 insertion site is preceded by a putative σB dependent promoter, which could explain the biofilm-negative phenotype by inactivation of genes downstream of purR. Interestingly, in B. subtilis the σB promoter within the purR gene seems to be silent (38). In S. epidermidis, regulation of biofilm expression by σB was predicted (19), suggesting that these genes could play an additional regulatory role or could act as the mediator of the σB regulation. Further experiments to elucidate the effect of these putative regulatory genes on the regulation of biofilm expression in S. epidermidis are under way.

The strongly biofilm-positive wild-type S. epidermidis 1457 displays a mucoid phenotype on PurpleGlcNAc, and all as-yet-characterized biofilm-negative Tn917 mutants displayed a nonmucoid phenotype under these conditions. A mucoid phenotype is often associated with exopolysaccharide formation (3, 24) and is associated with pathogenicity of a variety of bacteria (3, 34, 48). However, the linkage between biofilm expression and a mucoid phenotype in S. epidermidis is unclear. To elucidate this linkage, we carried out a Tn917 transposon mutagenesis with a subsequent screening for nonmucoid mutants. Two mutants M16 and M20 with a nonmucoid but still biofilm-positive phenotype could be isolated, and the genetic linkage to the observed phenotypes could be demonstrated by phage transduction. The Tn917 insertions of M16 were identified in a homologue to the glcT gene coding for a rho-independent antiterminator in S. carnosus and B. subtilis. Homologous genes were also observed in S. aureus. The Tn917 insertions of M20 was identified in a homologue to the glcA and glcB genes of S. carnosus and the ptsG gene of B. subtilis, which represents the glucose-specific EII proteins in the PTS of these species. Homologous genes were also observed in S. aureus; however, the sugar specificity of the S. aureus homologue is not yet characterized. The homology of the inactivated genes in M16 and M20 to these components of the PTS of S. carnosus and B. subtilis suggests that sugar transport via the PTS is necessary for a mucoid phenotype. Recently, it could be demonstrated that, besides icaADBC, a glucose-dependent factor is required for PIA synthesis and biofilm formation (10). However, sugar transport via this putative EII protein of the PTS is not essential for biofilm formation of S. epidermidis. Transcriptional analysis of glcT and glcA and investigations of the sugar specificity of the EII protein are under way to elucidate the mechanisms of the influence of the S. epidermidis PTS on the mucoid phenotype in S. epidermidis.

All of the newly identified genes involved in biofilm formation or expression of a mucoid phenotype of S. epidermidis are present in all published staphylococcal genomes (Fig. 2), indicating an important role for these genes in the cell biology of staphylococci. However, in S. aureus the localization of the homologous genes within the chromosome is conserved, whereas in S. epidermidis the genes belonging to the PTS system are localized in completely different chromosomal areas (Fig. 2), indicating major chromosomal rearrangements between icaADBC-positive and -negative S. epidermidis isolates.

The characterization of the new mutants gives evidence that the arbitrary PCR is a suitable tool for the rapid identification of Tn917 insertions in S. epidermidis. The primers for the established arbitrary PCR were adapted to the GC content of staphylococci. Therefore, we expect that this method is a useful tool for identifying Tn917 insertion sites of interest in all staphylococcal species.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rainer Laufs for continuous support.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants given to D.M., J.K.-M.K., and H.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba, T., F. Takeuchi, M. Kuroda, H. Yuzawa, K. Aoki, A. Oguchi, Y. Nagai, N. Iwama, K. Asano, T. Naimi, H. Kuroda, L. Cui, K. Yamamoto, and K. Hiramatsu. 2002. Genome and virulence determinants of high virulence community-acquired MRSA. Lancet 359:1819-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boucher, J. C., H. Yu, M. H. Mudd, and V. Deretic. 1997. Mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: characterization of muc mutations in clinical isolates and analysis of clearance in a mouse model of respiratory infection. Infect. Immun. 65:3838-3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christiansen, I., and W. Hengstenberg. 1996. Cloning and sequencing of two genes from Staphylococcus carnosus coding for glucose-specific PTS and their expression in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christiansen, I., and W. Hengstenberg. 1999. Staphylococcal phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phosphotransferase system—two highly similar glucose permeases in Staphylococcus carnosus with different glucoside specificity: protein engineering in vivo? Microbiology 145:2881-2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conlon, K. M., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2002. icaR encodes a transcriptional repressor involved in environmental regulation of ica operon expression and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 184:4400-4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conlon, K. M., H. Humphreys, and J. P. O'Gara. 2002. Regulation of icaR gene expression in Staphylococcus epidermidis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 216:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramton, S. E., C. Gerke, N. F. Schnell, W. W. Nichols, and F. Götz. 1999. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 67:5427-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramton, S. E., M. Ulrich, F. Götz, and G. Döring. 2001. Anaerobic conditions induce expression of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 69:4079-4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobinsky, S., K. Kiel, H. Rohde, K. Bartscht, J. K. M. Knobloch, M. A. Horstkotte, and D. Mack. 2003. Glucose-related dissociation between icaADBC transcription and biofilm expression by Staphylococcus epidermidis: evidence for an additional factor required for polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 185:2879-2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzpatrick, F., H. Humphreys, E. Smyth, C. A. Kennedy, and J. P. O'Gara. 2002. Environmental regulation of biofilm formation in intensive care unit isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Hosp. Infect. 52:212-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frebourg, N. B., S. Lefebvre, S. Baert, and J. F. Lemeland. 2000. PCR-based assay for discrimination between invasive and contaminating Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:877-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerke, C., A. Kraft, R. Sussmuth, O. Schweitzer, and F. Götz. 1998. Characterization of the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity involved in the biosynthesis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:18586-18593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Götz, F. 2002. Staphylococcus and biofilms. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1367-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Handwerger, S. 1994. Alterations in peptidoglycan precursors and vancomycin susceptibility in Tn917 insertion mutants of Enterococcus faecalis 221. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:473-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilmann, C., O. Schweitzer, C. Gerke, N. Vanittanakom, D. Mack, and F. Götz. 1996. Molecular basis of intercellular adhesion in the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1083-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilstrup, M., and J. Martinussen. 1998. A transcriptional activator, homologous to the Bacillus subtilis PurR repressor, is required for expression of purine biosynthetic genes in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 180:3907-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knezevic, I., S. Bachem, A. Sickmann, H. E. Meyer, J. Stülke, and W. Hengstenberg. 2000. Regulation of the glucose-specific phosphotransferase system (PTS) of Staphylococcus carnosus by the antiterminator protein GlcT. Microbiology 146:2333-2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knobloch, J. K. M., K. Bartscht, A. Sabottke, H. Rohde, H. H. Feucht, and D. Mack. 2001. Biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis depends on functional RsbU, an activator of the sigB operon: differential activation mechanisms due to ethanol and salt stress. J. Bacteriol. 183:2624-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knobloch, J. K. M., M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, P. M. Kaulfers, and D. Mack. 2002. Alcoholic ingredients in skin disinfectants increase biofilm expression of Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:683-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knobloch, J. K. M., M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2002. Evaluation of different detection methods of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 191:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knobloch, J. K. M., H. von Osten, M. A. Horstkotte, H. Rohde, and D. Mack. 2002. Minimal attachment killing (MAK): a versatile method for susceptibility testing of attached biofilm-positive and -negative Staphylococcus epidermidis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 191:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I. Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, C. Y., and J. C. Lee. 2000. Staphylococcal capsule, p. 361-366. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferretti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood (ed.), Gram-positve pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 25.Li, Z., D. D. Sledjeski, B. Kreikemeyer, A. Podbielski, and M. D. Boyle. 1999. Identification of pel, a Streptococcus pyogenes locus that affects both surface and secreted proteins. J. Bacteriol. 181:6019-6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mack, D. 1999. Molecular mechanisms of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation. J. Hosp. Infect. 43(Suppl.):S113-S125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mack, D., K. Bartscht, C. Fischer, H. Rohde, C. de Grahl, S. Dobinsky, M. A. Horstkotte, K. Kiel, and J. K. M. Knobloch. 2001. Genetic and biochemical analysis of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm accumulation. Methods Enzymol. 336:215-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack, D., W. Fischer, A. Krokotsch, K. Leopold, R. Hartmann, H. Egge, and R. Laufs. 1996. The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear β-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: purification and structural analysis. J. Bacteriol. 178:175-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mack, D., J. Riedewald, H. Rohde, T. Magnus, H. H. Feucht, H. A. Elsner, R. Laufs, and M. E. Rupp. 1999. Essential functional role of the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin of Staphylococcus epidermidis in hemagglutination. Infect. Immun. 67:1004-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack, D., H. Rohde, S. Dobinsky, J. Riedewald, M. Nedelmann, J. K. M. Knobloch, H. A. Elsner, and H. H. Feucht. 2000. Identification of three essential regulatory gene loci governing expression of Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 68:3799-3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mack, D., A. Sabottke, S. Dobinsky, H. Rohde, M. A. Horstkotte, and J. K. M. Knobloch. 2002. Differential expression of methicillin resistance by different biofilm-negative Staphylococcus epidermidis transposon mutant classes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:178-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mack, D., N. Siemssen, and R. Laufs. 1992. Parallel induction by glucose of adherence and a polysaccharide antigen specific for plastic-adherent Staphylococcus epidermidis: evidence for functional relation to intercellular adhesion. Infect. Immun. 60:2048-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKenney, D., J. Hubner, E. Muller, Y. Wang, D. A. Goldmann, and G. B. Pier. 1998. The ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect. Immun. 66:4711-4720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nassif, X., J. M. Fournier, J. Arondel, and P. J. Sansonetti. 1989. Mucoid phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae is a plasmid-encoded virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 57:546-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nedelmann, M., A. Sabottke, R. Laufs, and D. Mack. 1998. Generalized transduction for genetic linkage analysis and transfer of transposon insertions in different Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 287:85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neubauer, H., I. Pantel, and F. Götz. 1999. Molecular characterization of the nitrite-reducing system of Staphylococcus carnosus. J. Bacteriol. 181:1481-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Toole, G. A., L. A. Pratt, P. I. Watnick, D. K. Newman, V. B. Weaver, and R. Kolter. 1999. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:91-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersohn, A., J. Bernhardt, U. Gerth, D. Hoper, T. Koburger, U. Völker, and M. Hecker. 1999. Identification of σB-dependent genes in Bacillus subtilis using a promoter consensus-directed search and oligonucleotide hybridization. J. Bacteriol. 181:5718-5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rachid, S., S. Cho, K. Ohlsen, J. Hacker, and W. Ziebuhr. 2000. Induction of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation by environmental factors: the possible involvement of the alternative transcription factor sigB. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 485:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rachid, S., K. Ohlsen, U. Wallner, J. Hacker, M. Hecker, and W. Ziebuhr. 2000. Alternative transcription factor σB is involved in regulation of biofilm expression in a Staphylococcus aureus mucosal isolate. J. Bacteriol. 182:6824-6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rachid, S., K. Ohlsen, W. Witte, J. Hacker, and W. Ziebuhr. 2000. Effect of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations on polysaccharide intercellular adhesin expression in biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3357-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohde, H., J. K. M. Knobloch, M. A. Horstkotte, and D. Mack. 2001. Correlation of biofilm expression types of Staphylococcus epidermidis with polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis: evidence for involvement of icaADBC genotype-independent factors. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 190:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rupp, M. E., P. D. Fey, C. Heilmann, and F. Götz. 2001. Characterization of the importance of Staphylococcus epidermidis autolysin and polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in the pathogenesis of intravascular catheter-associated infection in a rat model. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1038-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rupp, M. E., J. S. Ulphani, P. D. Fey, K. Bartscht, and D. Mack. 1999. Characterization of the importance of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin/hemagglutinin of Staphylococcus epidermidis in the pathogenesis of biomaterial-based infection in a mouse foreign body infection model. Infect. Immun. 67:2627-2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rupp, M. E., J. S. Ulphani, P. D. Fey, and D. Mack. 1999. Characterization of Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin/hemagglutinin in the pathogenesis of intravascular catheter-associated infection in a rat model. Infect. Immun. 67:2656-2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saklani-Jusforgues, H., E. Fontan, and P. L. Goossens. 2001. Characterisation of a Listeria monocytogenes mutant deficient in d-arabitol fermentation. Res. Microbiol. 152:175-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saxild, H. H., K. Brunstedt, K. I. Nielsen, H. Jarmer, and P. Nygaard. 2001. Definition of the Bacillus subtilis PurR operator using genetic and bioinformatic tools and expansion of the PurR regulon with glyA, guaC, pbuG, xpt-pbuX, yqhZ-folD, and pbuO. J. Bacteriol. 183:6175-6183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schrager, H. M., S. Alberti, C. Cywes, G. J. Dougherty, and M. R. Wessels. 1998. Hyaluronic acid capsule modulates M protein-mediated adherence and acts as a ligand for attachment of group A streptococcus to CD44 on human keratinocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 101:1708-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sebulsky, M. T., D. Hohnstein, M. D. Hunter, and D. E. Heinrichs. 2000. Identification and characterization of a membrane permease involved in iron-hydroxamate transport in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 182:4394-4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stulke, J., I. Martin-Verstraete, M. Zagorec, M. Rose, A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 1997. Induction of the Bacillus subtilis ptsGHI operon by glucose is controlled by a novel antiterminator, GlcT. Mol. Microbiol. 25:65-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vats, N., and S. F. Lee. 2000. Active detachment of Streptococcus mutans cells adhered to epon-hydroxylapatite surfaces coated with salivary proteins in vitro. Arch. Oral Biol. 45:305-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weng, M., P. L. Nagy, and H. Zalkin. 1995. Identification of the Bacillus subtilis pur operon repressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:7455-7459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weng, M., and H. Zalkin. 2000. Mutations in the Bacillus subtilis purine repressor that perturb PRPP effector function in vitro and in vivo. Curr. Microbiol. 41:56-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zagorec, M., and P. W. Postma. 1992. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the ptsG gene of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 234:325-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zagorec, M., and M. Steinmetz. 1991. Construction of a derivative of Tn917 containing an outward-directed promoter and its use in Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137(Pt. 1):107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]