Abstract

The gene causing cystic fibrosis (CF) encodes the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a cAMP-regulated chloride channel. Mutations in this gene result in reduced transepithelial chloride permeability across tissues affected in CF. Consequently, restoring chloride permeability to these tissues may prove therapeutic. Here we report that a combination of forskolin, an adenylate cyclase activator, and milrinone, an inhibitor of class III phosphodiesterases, increases the magnitude of the potential difference across nasal epithelium of mice homozygous for the most common CF mutation, ΔF508, while neither drug alone has a significant effect on potential difference. Transgenic mice lacking CFTR do not respond to the milrinone/forskolin combination, indicating that the effect in ΔF508 mice requires CFTR. These results suggest that, by pharmacological means, at least partial CFTR-mediated electrolyte transport can be restored in vivo to CF tissues expressing ΔF508.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal genetic disorder affecting ≈1 in 2000 live births in North America, predominantly those of Caucasian ancestry (1). The disease is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (2–4), a cAMP-regulated chloride channel (5, 6). Accordingly, CF is characterized by a lack of cAMP-stimulated chloride conductance across the epithelia of numerous tissues, including the respiratory tree, pancreatic ducts, sweat glands, and intestines (1). Although a single amino acid deletion at phenylalanine 508 (ΔF508) accounts for about 70% of CF chromosomes (4), there are over 600 other mutations associated with the disease (L. C. Tsui, Cystic Fibrosis Genetic Analysis Consortium, personal communication). Genotype/phenotype studies show a strong association between the severity of disease in a patient and the mutations carried by the patient (8–10). When studied in heterologous expression systems, many of the mutations associated with milder CF symptoms, such as pancreatic sufficiency, appear to have more chloride channel activity than those mutations associated with more severe disease phenotypes (11, 12). Also, there are sequence variations in the CFTR gene that affect the level of normal CFTR mRNA produced by altering splicing efficiency (13, 14). These variations show a similar association in that the greater level of CFTR expressed, the milder the symptoms (15). Together, these observations suggest a model in which CF is caused by quantitative reductions in CFTR or qualitative changes in CFTR function, and that the severity of the disease corresponds to the level of CFTR activity in the tissue affected. This model predicts that elevating the level of CFTR activity in a CF-affected epithelium would be beneficial to CF patients. As a result, numerous therapeutic strategies have been proposed, including introduction of CFTR cDNA expression constructs into CF epithelial cells (16, 17) as well as increasing the activity (18–22) or quantity (23) of mutant CFTR molecules by pharmacological manipulation.

About 90% of CF patients carry at least one ΔF508 allele, making this mutation the most important target for strategies aimed at correcting the channel defect. However, correction of ΔF508 involves two obstacles. First, it is inefficiently processed, with most of the synthesized polypeptide being retained intracellularly and degraded (24). Second, once at the plasma membrane, the ΔF508 mutant channel has decreased activity relative to wild type (18–20) due to prolonged closed-channel intervals (19, 20). Both of these properties may contribute to the severe disease presentation associated with ΔF508. Despite these functional limitations, some ΔF508 must escape intracellular retention, as functional assays are capable of detecting CFTR channels in cells expressing only ΔF508 (18–20). The sensitivity of ΔF508 to cAMP-mediated stimulation is reduced relative to wild type (18) such that some compounds that increase Cl− currents across non-CF epithelia have no detectable effect on ΔF508 CF epithelia (25). We have found that a key step in eliciting ΔF508 activity from airway epithelial cells is optimizing the stimulus for those cells by identifying components of the signal transduction pathway through which CFTR is activated (26, 27). In cultured human airway epithelial cells, both primary and transformed, CF and non-CF, a combination of adenylate cyclase activator and a class III phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor was the most specific and potent activator of wild-type and mutant CFTR (26, 27). We therefore explored the possibility that this combination of drugs could induce ΔF508 CFTR activity to an appreciable degree in an epithelium in vivo.

METHODS

Nasal Potential Difference Measurements.

Nasal potential difference (PD) measurements were carried out according to method of Grubb et al. (28), with the following modifications. Perfusions were initiated in Hepes-buffered Ringers solution containing amiloride (100 μM) at a flow rate of 7 μl/min. When a plateau nasal PD value was achieved, the perfusing solution was switched to a chloride-free Ringers solution containing amiloride (100 μM) in which gluconate was substituted for chloride. No corrections for junction potential were made. After 2 min, perfusion was switched to chloride-free Ringers solution with amiloride but also containing the 10 μM forskolin/100 μM milrinone combination. Fluid movement through the catheter resulted in a delay of 30 sec before reaching the epithelium. For studies including chloride channel blockers, either 1 mM diphenylamine-2-carboxylate (DPC) or 500 μM 4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) were included in the perfusate throughout the experiment. Data are compared at 15-sec intervals over 4.5 min, in which the first time point corresponds to 2 min before addition of PDE inhibitors and/or forskolin.

Mouse Genotyping.

The ΔF508 mice used in this study were generated by targeted replacement of the wild-type exon 10 allele with the ΔF508 mutant allele. This manipulation also resulted in the neomycin phosphotransferase gene inserted in intron 10 as described (29). Mice were genotyped from tail clip DNA. For ΔF508 mice, 0.5 μg of DNA was amplified with oCF10 (5′-GGTACTATCAAAGAAAATATCATCTT-3′) and oCF51 (5′-TTATCACAACACTGACACTGACACAAGTAG-3′), which are specific for the ΔF508 allele (29). A duplicate DNA sample was amplified with oCF11 (5′-GGTACTATCAAAGAAAATATCAT-3′) and oCF51, which are specific for the wild-type allele. PCR was 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 20 sec, and 72°C for 1 min. cftr(−/−) mice were genotyped according to Koller et al. (30). To increase survival of CF animals, mice were fed a liquid diet as described by Eckman et al. (31). The cftr(−/−) mice (32) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were cared for in accordance with Case Western Reserve University institutional guidelines.

RESULTS

As an in vivo model of CF epithelia, mice carrying CFTR mutations have been generated and express many of the electrophysiological abnormalities found in CF patients (29, 32–34). In particular, the nasal epithelium of these animals serves as a model for human CF airway epithelium as it lacks the cAMP-dependent chloride current found in normal mice (28). Animals in which the CFTR gene has been disrupted by insertion of a premature stop codon have essentially the same electrophysiological abnormalities and pathology as animals carrying the ΔF508 mutation (29, 32, 33), with a notable exception in the ΔF508 mice described by van Doorninck and coworkers (35, 36), in which the ΔF508 mutation was inserted by a hit-and-run approach so that the introns do not retain selectable markers. Gallbladder epithelial cells from these animals have a small, but detectable, level of forskolin-stimulated ΔF508 CFTR activity. It has been speculated that this difference reflects the targeting strategies used to generate the mice, but no differences in mRNA levels were detected between normal and mutant alleles in either type of animal (29, 32). Presumably the reason for this discrepancy is more complicated than different levels of ΔF508 CFTR expression. The similarity of phenotypes between the rest of these CF animal models indicates that under normal physiological conditions the two genotypes have the same effect on epithelial physiology. Thus, comparing the phenotypically similar ΔF508 and cftr(−/−) animals should serve as an excellent controlled system in which to study pharmacologic agents for their ability to alter ΔF508 CFTR activity.

Nasal PD Measurements.

The PD assay is currently the only feasible way to make measurements in vivo on transepithelial ion transport. Although this assay has limitations, Grubb et al. (28) have shown that responses detected by this assay are consistent with those obtained by short-circuit measurements. We compared the three genotypes of mice used in this study with regards to steady-state PD, amiloride-sensitive PD, and response to replacement of chloride by gluconate. As Table 1 shows, the steady-state of the CF genotypes [ΔF508 and cftr(−/−)] are indistinguishable from each other, but substantially greater than that of the non-CF littermates. The steady-state values for non-CF of −9.8 ± 0.6 mV and cftr(−/−) of −24.2 ± 1.4 mV are comparable to those reported by others (28, 29). Also as reported, we found the amiloride-sensitive component of the PD to be greater in the CF animals than in the non-CF animals (Table 1), although our values for the CF animals [9.9 ± 1.2 for cftr(−/−) and 7.2 ± 0.7 for ΔF508] are lower than those reported for cftr(−/−) mice (28, 29). The effect of replacing chloride by gluconate showed a consistent, genotype effect as well. In the presence of amiloride, the change to low chloride causes the PD to hyperpolarize in non-CF mice, while the nasal epithelium of both CF genotypes continues to depolarize by about 3–3.5 mV over 2.5 min.

Table 1.

Genotype-specific PD values

| Genotype | cftr (+/+), cftr (+/−), cftr (+/ΔF508) | cftr (−/−) | cftr (ΔF508/ΔF508) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steady-state, mV | −9.8 ± 0.6 (33) | −24.2 ± 1.4 (12) | −22.9 ± 2.2 (12) |

| ΔPD (amiloride), mV | 5.3 ± 0.4 (12) | 9.9 ± 1.2 (5) | 7.2 ± 0.7 (5) |

| ΔPD (Cl− free), mV | −4.7 ± 1.8 (12) | 3.5 ± 0.6 (7) | 3.1 ± 0.5 (14) |

When perfused with Hepes-buffered Ringers solution (HBR), the steady-state nasal PD values of non-CF animals [cftr (+/+), cftr (+/−), and cftr (+/ΔF508)genotypes] are significantly lower (lumen negative) than mice of either of the CF genotypes [cftr (−/−) and cftr (ΔF5088/ΔF508)]. When amiloride is included in the perfusion, the amount of amiloride-sensitive PD is correspondingly greateer in the CF animals. Switching to HBR containing amilorde, but in which cholride has been replaced by gluconate, causes the PD of the non-CF mice to increase, making the lumen more negative, while the CF PDs continue to fall, Steady-state values are taken after a plateau of 30–60 sec, amiloride inhibition is detemined after 2-min exposure to drug and chloride-free responses determined at 2 min after exposure to gluconate-containing HBR. Number of animals examined for each set of conditions are given in parentheses.

The nasal epithelia of mice carrying at least one wild-type CFTR allele were then perfused with various PDE inhibitors to determine if the mouse airway is concordant with the human cells in terms of which PDE class most significantly regulates CFTR. The nasal epithelium was perfused with a chloride-free Ringers solution containing amiloride to reduce the contribution of sodium absorption to the PD. PDE inhibitors milrinone and amrinone, specific for class III cAMP PDEs, rolipram and Ro20–1724, specific for class IV cAMP-PDEs, IBMX, a nonselective PDE inhibitor, and dipyridamole, a class V, or cyclic guanosine monophosphate-PDE inhibitor, were compared for their ability to hyperpolarize the epithelium as an indicator of increased chloride secretion (Table 2). For comparison, the response to the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin is shown. As we found in human airway cells (26), milrinone had the greatest effect of PDE inhibitors on chloride permeability, hyperpolarizing the epithelium by ≈7 mV. Although not as potent as milrinone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), and amrinone also generated significant hyperpolarizing changes in PD (4.6 and 4.0 mV, respectively). The class IV inhibitor rolipram had a small, but significant, effect on nasal PD, while the other type IV inhibitor, Ro20–1724, did not. Dipyridamole, which should not influence cAMP levels, had no effect on CFTR activity either. These assays were performed in the absence of adenylate cyclase activation, implying that the PDE inhibitors are acting on basal levels of cAMP.

Table 2.

Comparison of the effects of specific PDE inhibitors on mouse nasal PD

| Stimulus | Action | ΔPD ± SEM (in mV) | n | P vs. control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 3 | ||

| Forskolin | Adenylate cyclase activator | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 3 | <0.0001* |

| Milrinone | Class III PDE inhibitor | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 5 | <0.0001* |

| Amrinone | Class III PDE inhibitor | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 5 | 0.0013* |

| Ro20-174 | Class IV PDE inhibitor | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 3 | 0.3516 |

| Rolipram | Class IV PDE inhibitor | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 4 | 0.0336 |

| IBMX | Nonselective PDE inhibitor | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 4 | 0.0004* |

| Dipyridamole | Class V PDE inhibitor | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 4 | 0.4192 |

PD measurements were carried out in the presence of forskolin or various PDE inhibitors. After the PD change induced by chloride-free perfusion plateaued, the response to the compounds listed were measured after a 2 minute exposure to the drugs. Comparison of means with control was evaluated by ANOVA and Dunn test with a Bonferroni correction. IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine.

Significance with α = 0.05 corresponds to a P value of 0.0071 or less.

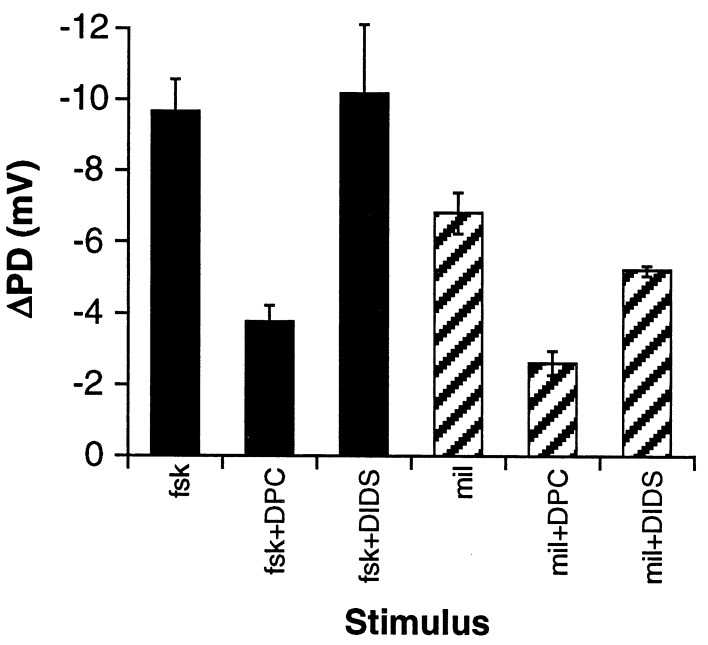

Pharmacology of the Response.

To test the hypothesis that milrinone acts through CFTR, PD measurements were made in which the epithelium was treated with the chloride channel blockers DPC, an inhibitor of CFTR chloride channel activity (37), or DIDS, a chloride channel blocker to which CFTR is relatively insensitive and which inhibits non-CFTR channels in cftr(−/−) mice (38). As Fig. 1 shows, milrinone behaves similarly to forskolin. DPC reduced forskolin- and milrinone-dependent stimulation by 60% (P = 0.00028 vs. forskolin) and 61% (P = 0.00031 vs. milrinone), respectively, and DIDS had a smaller but significant effect on the milrinone-induced PD change (ΔPD = 1.6 mV, or 24%, P = 0.023 vs. milrinone). Together with the data in Table 2, these results imply that class III PDEs have greater influence on CFTR activity in mouse nasal epithelium than class IV PDEs, as was found in human airway epithelial cells (26). The partial inhibition by DIDS also suggests that CFTR is likely the predominant activity stimulated by milrinone, but other non-CFTR pathways, including nonspecific transepithelial leak, may be involved as well.

Figure 1.

Changes in nasal PD are consistent with increased CFTR activity. PD measurements were carried out in the presence of DPC or DIDS. After the PD change induced by chloride-free perfusion plateaued, the response to forskolin (fsk; n = 3) and milrinone (mil; n = 5) were measured and the average change in PD (ΔPD) calculated. Error bars represent SEM.

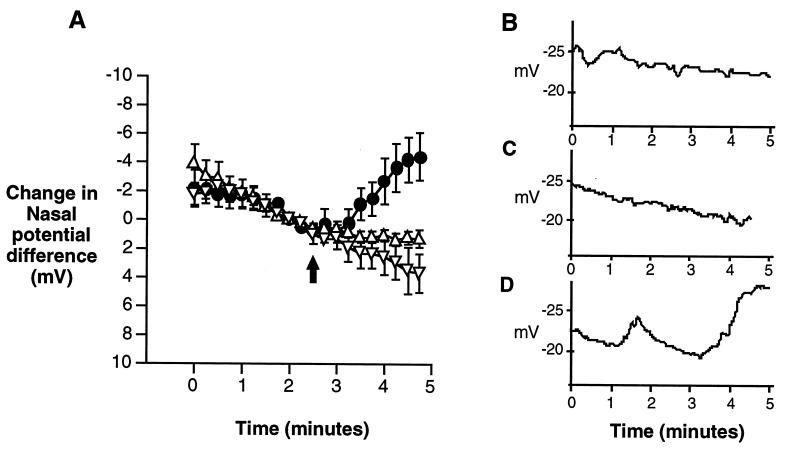

Activation of ΔF508.

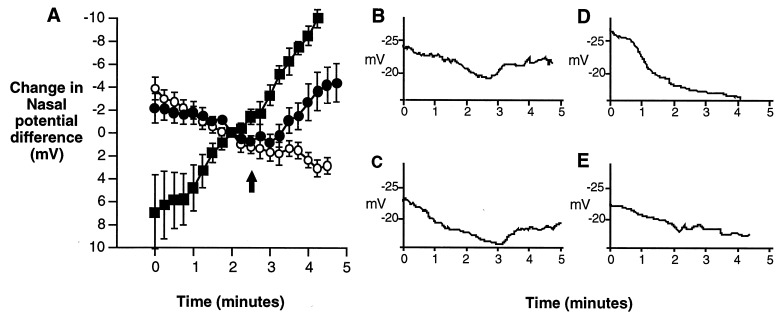

In human ΔF508 airway cells, a combination of adenylate cyclase activator and milrinone is necessary to stimulate CFTR chloride currents (27). Accordingly, neither forskolin nor milrinone, the most potent single activators of wild-type CFTR (Table 2), had an effect on the PD of ΔF508 mice, but when combined significantly increased the PD (Fig. 2). To support the notion that the response was due to CFTR activity, the ΔF508 mice were compared with non-CF littermates (ΔF508/wt or wt/wt) and cftr(−/−) mice as positive and negative controls, respectively. After perfusing the nasal cavity with a physiologic saline solution containing amiloride to inhibit sodium absorption, perfusion with a chloride-free solution containing amiloride stimulates a PD increase in the normal mouse, but not in the ΔF508/ΔF508 or cftr(−/−) mice (Fig. 3). These responses are similar to those reported in human nasal PDs, as the chloride-free perfusion creates a gradient for chloride secretion sufficient to stimulate chloride movement in normal, but not CF nasal epithelium (39). When forskolin and milrinone are included in the perfusate, the PD of the non-CF mice further increases to a net change of 15.9 mV after 4 min in chloride-free perfusion while the PD of cftr(−/−) mice is decreased (depolarized) by 8.0 mV. The nasal epithelia of ΔF508 mice, however, depolarize by 2.5 mV until milrinone and forskolin are added. By 2 min after addition of milrinone and forskolin, this stimulus hyperpolarizes the epithelium by ≈4.2 mV. Relative to the cftr(−/−) mice at the same time point, the ΔF508 mice are hyperpolarized by 6.9 mV. This comparison implies that milrinone and forskolin increase the ΔF508 PD through a CFTR-dependent mechanism, most likely by activation of CFTR chloride channels.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effects of forskolin, milrinone, and the combination of forskolin and milrinone on the nasal PD of ΔF508 mice. After achieving a steady-state PD in Hepes-buffered Ringers solution, perfusion was switched to a chloride-free Ringers solution containing amiloride (see Methods) at t = 0 min. At 2.5 min (shown by arrows) milrinone and/or forskolin reach the epithelium. (A) The nasal PD of ΔF508 homozygous mice exposed to 100 μM milrinone (•, n = 3) or 10 μM forskolin (▿, n = 3) is little changed in response to the drugs, but the combination of 10 μM forskolin and 100 μM milrinone (▾, n = 5) results in a significantly elevated PD. Data are plotted from t = 0, corresponding to 2.5 min before milrinone and forskolin reaching the epithelium, to t = 4.5 min, corresponding to 2 min after the epithelium is exposed to drugs. (B–D) Representative traces of a ΔF508 mouse nose exposed to milrinone alone (B), forskolin alone (C), or milrinone plus forskolin (D).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the effects of milrinone plus forskolin on the nasal PD of non-CF, cftr(−/−) and ΔF508 mice. After achieving a steady-state PD in Hepes-buffered Ringers solution, perfusion was switched to a chloride-free Ringers solution containing amiloride (see Methods) at t = 0 min. In non-CF mice, the chloride replacement stimulates a rise in the PD, but not in the CF animals. At 2.5 minutes, forskolin and milrinone reach the epithelium (designated by arrows). (A) Before milrinone (100 μM) and forskolin (10 μM) reach the epithelium, the PDs of cftr(−/−) mice are not significantly different from ΔF508 mice (at t = 120 sec, P = 0.35). About 1 min after addition of drugs (t = 210 sec), the responses begin to diverge and by t = 240 sec, the ΔF508 PDs are 6.9 mV greater, on average, than those of the cftr(−/−) animals (P = 0.039). The PDs of non-CF mice continue to rise after addition of forskolin and milrinone. Data are plotted from t = 0, corresponding to 2.5 min before milrinone and forskolin reaching the epithelium, to t = 4.5 min, corresponding to 2 min after the epithelium is exposed to drugs. Data points represent the mean for each time point and error bars represent SEM. ▪, Non-CF mice (n = 6); ○, cftr(−/−) mice (n = 8); and •, ΔF508 mice (n = 5). (B–E) Representative traces of responses to forskolin (10 μM) and milrinone (100 μM) from ΔF508 mice (B and C) and cftr(−/−) mice (D and E).

DISCUSSION

The results presented here indicate that the murine ΔF508 mutant, which manifests itself physiologically similar to the cftr(−/−) phenotype in the mouse model studied here, can be activated significantly in vivo by specific phosphodiesterase inhibition. Because of the relative accessibility of the airways to aerosolized compounds, treating CF airway disease with PDE inhibitors may be a feasible approach to therapy, as suggested previously (18). Despite these encouraging findings, there are caveats that must be considered. First, it is not clear whether the mouse ΔF508 CFTR is impaired to the same degree as the human counterpart, either in terms of its processing efficiency or ability to be activated. Murine ΔF508, like human ΔF508 CFTR, is incompletely processed relative to wild-type CFTR (36), but the proportion of incompletely glycosylated ΔF508 appears to be greater in human than in the mouse. The processing defect associated with ΔF508 has been shown to be a temperature-sensitive phenomenon (40), so a possible explanation is that the mouse and human differ in their temperatures and hence the amount of CFTR maturely glycosylated. However, the mouse body temperature is nearly identical to that of human, 36.5–38°C (41), suggesting temperature differences between mouse and human do not account for the ability to activate the murine CFTR mutant.

The epithelia of the ΔF508 mice studied here (29) and those of College et al. (34) are clearly impaired with regards to their short-circuit response to forskolin, consistent with human tissues. Although the inability of these mice to respond to forskolin is consistent with the original description of the mice, it must yet be determined how the level of activity found in the ΔF508 mouse compares to that in humans. Also, even though chloride transport is defective in CF, it is not clear that increasing CFTR activity in this way will correct the critical defects associated with CF. For instance, it has been proposed that ΔF508 may alter membrane turnover and even organelle pH (42, 43). It is unclear how these processes will be influenced by PDE inhibition. Similarly, sodium absorption across the airway epithelium is increased in CF and thought to contribute to the pathology in CF (44). The sodium channels responsible for this absorption in the airway appear to be regulated by the presence of functional CFTR (45), but their activity can be increased in response to β-adrenergic stimulation in the absence of CFTR (7, 44, 45). It is therefore possible that increasing chloride channel activity may restore regulation to the sodium channels, or that the same manipulation that increases ΔF508 activity may further increase sodium absorption. Nonetheless, the results presented here clearly indicate that an impaired CFTR expressed at endogenous levels in vivo can generate significant activity, providing an appropriate pharmacological stimulus is applied. This ability to increase mutant CFTR activity in vivo allows us to test prospects of a new pharmacological therapy for CF.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Eckman and C. Cotton for helpful discussions on maintaining CF mice and assistance in establishing the nasal PD assay, respectively. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL-50160, and by grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- PD

potential difference

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- DPC

diphenylamine-2-carboxylate

- DIDS

4,4′-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid

References

- 1.Welsh M J, Tsui LC, Boat T F, Beaudet A L. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease. 7th Ed. Scriver C R, Beaudet A L, Sly W S, Valle D, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1995. pp. 3799–3863. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rommens J M, Iannuzzi M C, Kerem B, Drumm M L, Melmer G, Dean M, Rozmahel R, Cole J L, Kennedy D, Hidaka N, Zsiga M, Buchwald M, Riordan J R, Tsui L-C, Collins F S. Science. 1989;245:1059–1065. doi: 10.1126/science.2772657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riordan J R, Rommens J M, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, Zielenski J, Lok S, Plavsic N, Chou J L, Drumm M L, Iannuzzi M C, Collins F S, Tsui L-C. Science. 1989;245:1066–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerem B, Rommens J M, Buchanan J A, Markiewicz D, Cox T K, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui L C. Science. 1989;245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson M P, Gregory R J, Thompson S, Souza D W, Paul S, Mulligan R C, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Science. 1991;253:202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bear C E, Li C H, Kartner N, Bridges R J, Jensen T J, Ramjeesingh M, Riordan J R. Cell. 1992;68:809–818. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ismailov I I, Awayda M S, Jovov B, Berdiev B K, Fuller C M, Dedman J R, Kaetzel M, Benos D J. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4725–4732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristidis P, Bozon D, Corey M, Markiewicz D, Rommens J, Tsui L C, Durie P. Am J Hum Genet. 1992;50:1178–1184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gan K H, Veeze H J, van den Ouweland A M, Halley D J, Scheffer H, van der Hout A, Overbeek S E, de Jongste J C, Bakker W, Heijerman H G. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:95–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Cystic Fibrosis Genotype-Phenotype Consortium. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1308–1313. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310283291804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheppard D N, Ostedgaard L S, Winter M C, Welsh M J. EMBO J. 1995;14:876–883. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheppard D N, Rich D P, Ostedgaard L S, Gregory R J, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Nature (London) 1993;362:160–164. doi: 10.1038/362160a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu C S, Trapnell B C, Curristin S, Cutting G R, Crystal R G. Nat Genet. 1993;3:151–156. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Highsmith W E, Burch L H, Zhou Z, Olsen J C, Boat T E, Spock A, Gorvoy J D, Quittel L, Friedman K J, Silverman L M, Boucher R C, Knowles M R. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:974–980. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410133311503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chillon M, Casals T, Mercier B, Bassas L, Lissens W, Silber S, Romey M C, Ruiz Romero J, Verlingue C, Claustres M, Nunes V, Férec C, Estivill X. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1475–1480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drumm M L, Pope H A, Cliff W H, Rommens J M, Marvin S A, Tsui L C, Collins F S, Frizzell R A, Wilson J M. Cell. 1990;62:1227–1233. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich D P, Anderson M P, Gregory R J, Cheng S H, Paul S, Jefferson D M, McCann J D, Klinger K W, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Nature (London) 1990;347:358–363. doi: 10.1038/347358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drumm M L, Wilkinson D J, Smit L S, Worrell R T, Strong T V, Frizzell R A, Dawson D C, Collins F S. Science. 1991;254:1797–1799. doi: 10.1126/science.1722350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, Crystal R G, Pavirani A, Lecocq J P, Lazdunski M. Nature (London) 1991;354:526–528. doi: 10.1038/354526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haws C M, Nepomuceno I B, Krouse M E, Wakelee H, Law T, Xia Y, Nguyen H, Wine J J. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1544–C1555. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.5.C1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eidelman O, Guay Broder C, van Galen P J, Jacobson K A, Fox C, Turner R J, Cabantchik Z I, Pollard H B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5562–5566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becq F, Jensen T J, Chang X B, Savoia A, Rommens J M, Tsui L C, Buchwald M, Riordan J R, Hanrahan J W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9160–9164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato S, Ward C L, Krouse M E, Wine J J, Kopito R R. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:635–638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng S H, Gregory R J, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza D W, White G A, O’Riordan C R, Smith A E. Cell. 1990;63:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grubb B, Lazarowski E, Knowles M, Boucher R. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:454–460. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelley T J, al Nakkash L, Drumm M L. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;13:657–664. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.6.7576703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley T J, Al-Nakkash L, Cotton C U, Drumm M L. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:513–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI118819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grubb B R, Vick R N, Boucher R C. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C1478–C1483. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeiher B G, Eichwald E, Zabner J, Smith J J, Puga A P, McCray P B, Jr, Capecchi M R, Welsh M J, Thomas K R. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2051–2064. doi: 10.1172/JCI118253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koller B H, Kim H S, Latour A M, Brigman K, Boucher R C, Jr, Scambler P, Wainwright B, Smithies O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10730–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckman E A, Cotton C U, Kube D M, Davis P B. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L625–L630. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.5.L625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snouwaert J N, Brigman K K, Latour A M, Malouf N N, Boucher R C, Smithies O, Koller B H. Science. 1992;257:1083–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratcliff R, Evans M J, Cuthbert A W, MacVinish L J, Foster D, Anderson J R, Colledge W H. Nat Genet. 1993;4:35–41. doi: 10.1038/ng0593-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colledge W H, Abella B S, Southern K W, Ratcliff R, Jiang C, Cheng S H, MacVinish L J, Anderson J R, Cuthbert A W, Evans M J. Nat Genet. 1995;10:445–452. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Doorninck J H, French P J, Verbeek E, Peters R H, Morreau H, Bijman J, Scholte B J. EMBO J. 1995;14:4403–4411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.French P J, van Doorninck J H, Peters R H P C, Verbeek E, Ameen N A, Marino C R, de Jonge H R, Bijman J, Scholte B J. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1304–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI118917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarty N A, McDonough S, Cohen B N, Riordan J R, Davidson N, Lester H A. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:1–23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valverde M A, O’Brien J A, Sepulveda F V, Ratcliff R, Evans M J, Colledge W H. Pflügers Arch. 1993;425:434–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00374869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knowles M R, Paradiso A M, Boucher R C. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:445–455. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.4-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Denning G M, Anderson M P, Amara J F, Marshall J, Smith A E, Welsh M J. Nature (London) 1992;358:761–764. doi: 10.1038/358761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harkness J E. In: The Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents. Harkness J E, Wagner J E, editors. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradbury N A, Jilling T, Berta G, Sorscher E J, Bridges R J, Kirk K L. Science. 1992;256:530–532. doi: 10.1126/science.1373908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barasch J, Kiss B, Prince A, Saiman L, Gruenert D, al Awqati Q. Nature (London) 1991;352:70–73. doi: 10.1038/352070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boucher R C, Stutts M J, Knowles M R, Cantley L, Gatzy J T. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1245–1252. doi: 10.1172/JCI112708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stutts M J, Canessa C M, Olsen J C, Hamrick M, Cohn J A, Rossier B C, Boucher R C. Science. 1995;269:847–850. doi: 10.1126/science.7543698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]