Abstract

The faithful replication of the genome, coupled with the accurate repair of DNA damage, is essential for the maintenance of chromosomal integrity. The MMS22 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae plays an important but poorly understood role in preservation of genome integrity. Here we describe a novel gene in Schizosaccharomyces pombe that we propose is a highly diverged ortholog of MMS22. Fission yeast Mms22 functions in the recovery from replication-associated DNA damage. Loss of Mms22 results in the accumulation of spontaneous DNA damage in the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle and elevated genomic instability. There are severe synthetic interactions involving mms22 and most of the homologous recombination proteins but not the structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1, which is required for survival of broken replication forks. Mms22 forms spontaneous nuclear foci and colocalizes with Rad22 in cells treated with camptothecin, suggesting that it has a direct role in repair of broken replication forks. Moreover, genetic interactions with components of the DNA replication fork suggest that Mms2 functions in the coordination of DNA synthesis following damage. We propose that Mms22 functions directly at the replication fork to maintain genomic integrity in a pathway involving Mus81-Eme1.

THE success of all living organisms depends on their ability to distribute accurate copies of their genome to daughter cells during each round of cell division. This task must be accomplished against a backdrop of a plethora of DNA lesions that can arise during normal cellular metabolism or through the actions of exogenous genotoxins. To combat this, eukaryotic organisms have evolved a variety of mechanisms that sense DNA damage and facilitate its repair. These mechanisms include specific DNA repair processes such as homologous recombination (HR), nonhomologous end joining, and nucleotide excision repair, as well as checkpoint mechanisms that delay cell cycle progression and coordinate DNA repair.

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, one specific protein that has been implicated in DNA repair is Brc1, which is a nonessential protein with six-BRCT (BRCA1 C-terminal) domains. Brc1 is thought to function primarily in S-phase where it aids in the replication of damaged DNA (Verkade et al. 1999; Sheedy et al. 2005). Brc1 was initially identified as a high-copy suppressor of smc6-74 (Verkade et al. 1999), which encodes a subunit of the essential “structural maintenance of chromosomes” Smc5/6 complex that functions in chromosome organization and DNA repair (Lehmann et al. 1995; McDonald et al. 2003; Harvey et al. 2004; Pebernard et al. 2004, 2006). The Brc1-mediated rescue of smc6-74 is thought to proceed via a novel Rhp18-dependent mechanism, utilizing multiple nucleases to facilitate the initial cleavage of abnormal structures that arise due to compromised Smc5/6 function and their subsequent processing by HR (Sheedy et al. 2005; Lee et al. 2007). Loss of Brc1 function results in sensitivity to a range of DNA-damaging drugs that generate lesions specifically during S-phase or impede DNA replication (Verkade et al. 1999; Sheedy et al. 2005).

Brc1 is related to the 6-BRCT repeat proteins Rtt107p (Esc4p) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and PTIP in humans, both of which have been implicated in the response to DNA damage (Jowsey et al. 2004; Rouse 2004). Budding yeast Rtt107p promotes the resumption of DNA synthesis after damage (Rouse 2004) and has been postulated to act as a protein scaffold at stalled replication forks where it recruits or modulates the function of other proteins required for the restart of DNA replication (Chin et al. 2006). In line with this, Rtt107p physically interacts with Slx4, a component of the Slx1-Slx4 structure-specific nuclease, and Slx4-dependent phosphorylation of Rtt107p by Mec1 has been proposed to be critical for replication restart following alkylation damage (Roberts et al. 2006). Rtt107p has also been shown by yeast two-hybrid analysis to interact with HR mediators and with Tof1 (Chin et al. 2006), a subunit of the replication-pausing complex Tof1-Csm3, which associates with unperturbed and stalled replication forks and is required to prevent uncoupling of Cdc45 and the MCM complex from DNA synthesis during hydroxyurea (HU) arrest (Katou et al. 2003). Similarly, Rtt107p was identified as an interactor of the DNA repair protein Mms22p in a high-throughput study and also by yeast two-hybrid analysis (Ho et al. 2002; Chin et al. 2006). MMS22 was initially identified as a gene required for resistance to ionizing radiation (IR) (Bennett et al. 2001); however, MMS22 mutants also display hypersensitivities to HU, methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), camptothecin (CPT), and etoposide, agents that result in DNA damage predominantly in S-phase (Chang et al. 2002; Araki et al. 2003; Baldwin et al. 2005).

MMS22 was also uncovered in a screen for mutants that are lethal in combination with mcm10-1, a thermosensitive allele of the DNA replication factor MCM10 (Araki et al. 2003), suggesting that Mms22p functions to resolve replication intermediates or to prevent damage caused by blocked replication forks (Araki et al. 2003). Mms22p is thought to function downstream in a pathway involving the DNA repair protein Mms1p (Araki et al. 2003); however, the precise mechanism of repair employed by this pathway is unknown, and homologs of Mms1p and Mms22p have not yet been identified in S. pombe or in higher eukaryotes. In view of the importance of this DNA repair complex in S. cerevisiae, we undertook a detailed sequence analysis to attempt to identify a fission yeast homolog of MMS22.

Here we report the identification and initial characterization of a novel fission yeast gene that is a putative ortholog of budding yeast MMS22. Our studies indicate that S. pombe mms22+ has a central role in preserving genome integrity during DNA replication and is vital for viability following DNA replication-associated damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and genetic methods:

Standard procedures and media for S. pombe genetics were used as previously described (Moreno et al. 1991). The entire open reading frame of mms22+ was replaced with the hygromycin B (HphMx6) or kanamycin (KanMx6) resistance markers as described (Bahler et al. 1998). Ectopic expression of GFP-Mms22 was from the pRep41-N-GFP plasmid under control of the attenuated thiamine-repressible nmt41 promoter. Strains used are listed in supplemental Table S1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/ (Nakamura et al. 2004).

Microscopy:

Cells were photographed using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with a Photometrics Quantix CCD camera. Rad22-YFP-expressing strains were cultured in yeast extract with supplements (YES) for at least 16 hr before foci quantification and at least 250 nuclei were scored in three independent experiments. Strains expressing pRep41-N-GFP-mms22+ were grown in EMM supplemented media containing thiamine for 20 hr before imaging. For quantification of GFP-Mms22 foci following CPT treatment, cultures were grown for 20 hr and then split into two. To one culture, a final concentration of 30μm CPT in DMSO was added, while the other culture had 0.3% (v/v final) DMSO added as a control. Treatment was for 3 hr at 30°. All microscopy was conducted on live, midlog phase cells, except for cultures to be DAPI stained, which were fixed in 70% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature, washed, and pelleted before resuspension in 5 μl of DAPI solution (500 μg/ml).

Minichromosome instability assay:

Minichromosome loss was measured as previously described (Allshire et al. 1995). Briefly, 500–1000 cells from individual Ade+ colonies were plated on adenine-limiting (12 mg/liter) plates, incubated at 30° for 3 days and then at 4° for 1 day to allow deepening of the red color in Ade− colonies. The number of chromosome loss events per division was determined as the number of colonies with a red sector equal to, or greater than, half the colony, divided by the sum of white and sectored colonies.

Survival assays:

For chronic exposures, midlog phase cultures were resuspended to 1 × 107 cells/ml and serially diluted fivefold. Dilutions were spotted onto YES agar plates or YES agar containing the indicated amounts of MMS, CPT, or HU (selective minimal media was used for experiments involving ectopic GFP-Mms22 expression). For acute exposures to IR and UV-induced damage, 1000 cells were plated onto triplicate YES agar plates and immediately irradiated with the indicated dose. Alternatively, YES plates were spotted with serial dilutions of cells, as for chronic drug exposure, and irradiated with the indicated dose. For survival of acute exposure to HU, midlog phase cells were cultured in YES media containing 12 mm HU for 10 hr. At the indicated time points, samples were taken, HU was washed out, and 1000 cells were plated onto YES agar plates in triplicate. For all survival assays, recovery was for 2–3 days at 30° unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Identification of S. pombe mms22+:

By focusing on an N-terminal core homology region that is most highly conserved between S. cerevisiae MMS22 and its budding yeast homologs, we were able to use position-specific iterated BLAST (Altschul et al. 1997; Schaffer et al. 2001) to identify a related gene in other divergent fungal species, including S. pombe (represented in Figure 1A). All of these genes encode very large proteins that range in size from ∼1400 to ∼2700 amino acids. Fission yeast SPAC6B12.02c+ encodes a protein of 1888 residues (Mw 217.4 kDa). Alignment of S. cerevisiae Mms22p and S. pombe SPAC6B12.02c proteins with the EMBOSS pairwise alignment (needle) algorithm (EMBL-EBI) indicated that the two proteins share 18.4% identity and 32.3% similarity over their full-length sequences. On the basis of our alignments, we predict that SPAC6B12.02c+ is a putative homolog of MMS22, and the relatively low identity may be explained by the fact that S. cerevisiae and S. pombe are highly divergent yeasts. Therefore, SPAC6B12.02c+ was named mms22+.

Figure 1.—

Identification of a putative homolog of MMS22 in S. pombe. (A) A schematic of putative MMS22 homologs in representative fungi showing areas of homology in the N and the C terminus and the corresponding amino acid alignments. The N-terminal homology domain spans S. cerevisiae Mms22p residues 196–292, Coccidioides immitis CIMG_05124 residues 403–499, Aspergillus nidulans AN6261.2 residues 522–614, and S. pombe SPAC6B12.02c (hereafter named Mms22) residues 246–337. The C-terminal homology domain incorporates S. cerevisiae Mms22p residues 1055–1234, CIMG_05124 residues 1615–1815, AN6261.2 residues 1748–1949, and S. pombe Mms22 residues 1319–1517. White text on a solid background indicates amino acid identity and solid text on a shaded background indicates conservative amino acid substitutions. (B) Survival curves of mms22Δ mutants exposed to increasing doses of IR or UV. A total of 500–1000 cells were plated on YES agar in triplicate and immediately exposed to the indicated dose of IR or UV irradiation. Colony numbers were counted following incubation at 30° for 2–3 days and the mean colony number for each dose represented graphically (with untreated normalized to 100% survival). The sensitivity of a rad32Δ mutant was analyzed as positive control. (C) Phenotypes of mms22Δ mutants. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were plated on YES agar exposed to the indicated DNA-damaging agent and incubated at 30° for 2–3 days.

Mms22 is important during a perturbed S-phase:

Deletion of mms22+ produced viable haploid cells that formed small colonies in the absence of any genotoxic stress (Figure 1C). The mms22Δ colonies contained many dead or elongated cells (Figure 2A) that are typical of mutants defective in DNA replication or mutants that are unable to repair DNA breaks that can arise spontaneously during DNA replication. In line with this, the plating efficiency of mms22Δ mutants was, on average 40%, compared to 84% for wild type (data not shown). Similarly, the average doubling time of mms22Δ mutants was ∼181 min in rich media at 32°, compared to 118 min for wild-type strains cultured under the same conditions (data not shown). Quantitative analysis confirmed that mms22Δ cultures contained an elevated number of uninucleate cells that are indicative of a checkpoint delay in cell cycle progression (Figure 2A). In fission yeast, Cds1 is the effector kinase of the DNA replication checkpoint that is activated when replication forks stall, whereas Chk1 enforces the G2-M checkpoint that is activated when DNA is damaged (Boddy and Russell 2001). Elimination of Chk1, but not of Cds1, reduced the elongated phenotype of most mms22Δ cells (Figure 2A), indicating that mms22Δ cells accumulate DNA structures that activate the Chk1-dependent DNA damage checkpoint.

Figure 2.—

Deletion of Chk1 reduces the elongated phenotype of mms22 mutants. (A) Cells were cultured to midlog phase in YES medium, fixed in 70% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature, and DAPI stained to visualize the nuclei and morphology of the cell. At least 250 cells were scored in three independent experiments and assigned to a particular cell cycle phase as previously described (Noguchi et al. 2004). Mean values were plotted with error bars representing the standard deviation about the mean. (B) Mms22 is not required for checkpoint activation in response to HU. Cells were cultured to midlog phase in YES medium and the culture was split into two. One culture was pelleted, immediately fixed in 70% ethanol for 10 min at room temperature, and DAPI stained, while the other culture was incubated in the presence of 12 mm HU for 4 hr prior to fixation and DAPI staining. Representative images are displayed.

S. cerevisiae mms22Δ cells are hypersensitive to a variety of DNA-damaging agents, including MMS, HU, CPT, and topoisomerase II-mediated DNA damage, and are moderately sensitive to UV and IR (Bennett et al. 2001; Chang et al. 2002; Araki et al. 2003; Baldwin et al. 2005); thus we analyzed whether fission yeast mms22Δ cells were sensitive to DNA-damaging agents. IR generates a number of lesions, including single-strand and double-strand breaks (DSBs), as well as base modification and damage, but its toxicity arises mainly from DSBs (Ward 1988). Unlike HR mutants that are profoundly sensitive to IR, we found that mms22Δ mutants were not hypersensitive to IR (Figure 1B). Similarly, we found that mms22Δ mutants were sensitive to UV only at high doses (Figure 1B). These data indicate that Mms22 is not essential for repair of IR-induced DSBs or UV-induced DNA lesions.

To address whether loss of Mms22 function results in sensitivity to agents that impede DNA replication, we assessed the growth of mms22Δ mutants following chronic exposure to agents that stall replication forks. HU is a ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, which arrests replisome progression by depleting the cellular pool of dNTPS, whereas MMS impedes replication fork progression by alkylating DNA template bases. Cells disrupted for mms22 were sensitive to HU (Figures 1C and 3B) and hypersensitive to MMS (Figure 1C), suggesting that the function of Mms22 is important in the recovery from replication fork stalling.

Figure 3.—

Mms22 has checkpoint-independent functions. (A) Phenotypes of mms22 mutants in checkpoint kinase-deficient backgrounds. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were plated on YES agar exposed to the indicated DNA-damaging agent and incubated at 30° for 2–3 days. (B) Phenotypes of mms22 mutants in checkpoint kinase-deficient backgrounds following acute exposure to UV and HU. For UV exposure, 1000 cells were plated onto triplicate YES agar plates and immediately irradiated with the indicated dose. For survival of acute exposure to HU, midlog phase cells were cultured in YES media containing 12 mm HU for 10 hr. At 0 hr, 1000 cells were plated onto YES agar plates in triplicate and, at the indicated time points, the same culture volume was taken, HU was washed out, and the cells were plated in triplicate. Survival was estimated relative to untreated cells. For all survival assays, recovery was for 2–3 days at 30° unless otherwise stated.

We also examined whether Mms22 has a role in the tolerance of S-phase-associated DNA breaks using the topoisomerase-I (Top-I)-inhibitor CPT. CPT stabilizes Top-I-DNA cleavage complexes, which can result in DSB formation when the replication fork collapses on encountering Top-I-mediated nicks in the template DNA (Pommier 2006). We observed that mms22Δ mutants were hypersensitive to CPT, even at very low doses (Figure 1C), which, together with the sensitivity to HU and MMS, indicates an important function for Mms22 in the recovery from replication fork damage and stalling.

Genetic interactions with checkpoint mutations:

To address whether Mms22 functions in the checkpoint response to either DNA damage or replication stress, we performed experiments to uncover genetic interactions between mms22 and cds1 or chk1. We found that mms22Δ chk1Δ cells were more sensitive to low doses (10–25 J/m2) of UV than either mms22Δ or chk1Δ alone (Figure 3, A and B), indicating that the modest UV survival defects caused by the absence of Mms22 are enhanced in the absence of a DNA damage checkpoint arrest. A similar interaction was seen following IR and on chronic exposure to 2 mm HU (Figure 3A). Similarly, following 8–10 hr of acute exposure to 12 mm HU, the double mms22Δ chk1Δ mutant showed reduced viability compared to mms22Δ or chk1Δ alone (Figure 3B). There was no genetic interaction between mms22Δ and cds1Δ in response to UV or IR (Figure 3, A and B), although the double mms22Δ cds1Δ showed a growth defect and an enhanced sensitivity to chronic low doses of HU (1–1.25 mm) relative to mms22Δ or cds1Δ alone (Figure 3A), as well as additive sensitivity following 1–4 hr of acute HU exposure (Figure 3B). Moreover, loss of Mms22 was detrimental to the growth of cells defective in both Cds1 and Chk1 in response to UV and IR (Figure 3, A and B). Similarly, following chronic exposure to 1 mm HU, the triple mutant was more sensitive than either mms22Δ or the double cds1Δ chk1Δ strain (Figure 3A), suggesting that Mms22 has a checkpoint-independent function at least in the tolerance of these DNA-damaging agents. The hypersensitivity of mms22Δ to MMS and to CPT made accurate comparisons for sensitivity to these agents difficult.

Finally, we examined whether Mms22 is involved in checkpoint activation in the response to HU. The majority of cells in mms22Δ, and both the mms22Δ cds1Δ and the mms22Δ chk1Δ cultures, arrested division with an elongated phenotype, whereas checkpoint failure in response to HU in a cds1Δ chk1Δ background resulted in a “cut” phenotype, which is diagnostic of checkpoint failure and subsequent mitotic catastrophe (Figure 2B). These data confirm that the intra-S-phase checkpoint can be activated in response to HU independently of Mms22. Together, these synergistic interactions of mms22 with cds1 and chk1 suggest that Mms22 has functions that are at least partially independent of Cds1 and Chk1 and that Mms22 is not required upstream for the activation of either checkpoint kinase in response to HU.

Mms22 is required to maintain genomic stability:

To confirm that mms22 mutants display an elongated phenotype due to the presence of DNA damage, we analyzed the effect of mms22Δ on the formation of Rad22 foci. Rad22 is the fission yeast homolog of the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein Rad52, which concentrates into bright visible foci at sites of DSB repair (Du et al. 2003). Approximately 14% of asynchronous wild-type nuclei contained one or more Rad22-YFP foci, compared to 53% in mms22Δ mutants (Figure 4A), suggesting that loss of mms22 function leads to elevated spontaneous DNA damage.

Figure 4.—

Spontaneous DNA damage occurs in the absence of Mms22. (A) Elevated Rad22-YFP foci arise in the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle in an mms22Δ background. Cells were cultured to midlog phase in YES medium and imaged live. The numbers of foci in at least 250 nuclei representing different phases of the cell cycle were scored in three independent experiments, and mean values were plotted with error bars representing the standard deviation of the mean. (B) Elevated spontaneous minichromosome 16 loss associated with disruption of Mms22 function. Cells containing the minichromosome are ade+ due to allelic complementation. Cells from individual Ade+ colonies were plated on adenine-limiting plates and the percentage of chromosome loss events per division was determined. The actual numbers are displayed under the chart (at least half red/total colonies).

As Mms22 is important for the survival of S-phase-specific damage, we hypothesized that the spontaneous damage might arise during DNA replication. To explore this, the cell cycle position of cells containing Rad22-YFP foci was determined. We observed that Rad22-YFP foci were specifically elevated in the S- and G2-phases in mms22Δ cells (Figure 4A), suggesting the presence of damaged DNA during these cell cycle phases in the absence of Mms22 function.

To determine whether the DNA damage that we observed in mms22 strains translates into genomic instability, we utilized strains that contained the three chromosomes of haploid S. pombe, as well as a copy of minichromosome 16 (Ch16), to analyze spontaneous chromosomal instability (Prudden et al. 2003). Ch16 is a highly stable 530-kb linear minichromosome, containing a centric region of chromosome III (Niwa et al. 1986). Ch16 encodes an ade6-M216 point mutation, which, when present in a background with an ade6-M210 heteroallele on chromosome III, results in an ade+ phenotype through allelic complementation (Figure 4B). The spontaneous loss of Ch16 was monitored in wild-type and mms22Δ backgrounds by growth on media lacking adenine. In this assay, mms22Δ mutants experienced an ∼35-fold increase in spontaneous loss of the minichromosome per cell division relative to wild type (Figure 4B).

In summary, mms22Δ mutants display spontaneous DNA damage as judged by the Chk1-dependent cell cycle delay and elevated Rad22 foci, and together with the increased spontaneous minichromosome 16 loss, these data suggest that Mms22 function is essential to maintain genomic stability in fission yeast.

Mms22 forms nuclear foci:

A number of proteins involved in DNA repair or checkpoint responses concentrate into foci in response to damage (Lisby et al. 2004), therefore we were interested to see if Mms22 localizes to punctate structures in S. pombe. Ectopic GFP-Mms22 was expressed under the control of the thiamine-repressible nmt promoter. In the presence of thiamine, GFP-Mms22 formed spontaneous nuclear foci due to leaky expression from the promoter (Figure 5, A and B). Under repressed conditions, the pRep41-N-GFP-mms22+ plasmid encodes a functional protein, as it rescues the growth defect and MMS, CPT, and HU sensitivity of mms22Δ cells (data not shown).

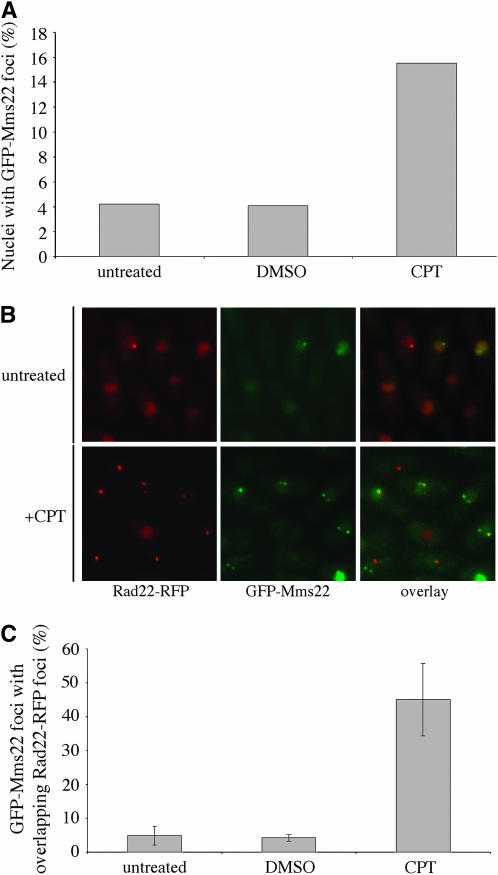

Figure 5.—

Mms22 forms nuclear foci that increase in response to DNA damage. (A) Cells expressing ectopic GFP-Mms22 were cultured for 20 hr to midlog phase in selective medium containing thiamine. The culture was split into three, one of which was analyzed immediately as the starting culture, and the other two of which were treated with CPT or DMSO as stated in the materials and methods section. For each culture, foci were scored in at least 250 live nuclei in three independent experiments. A representative data set from one experiment is shown due to variable GFP-Mms22 expression between individual experiments. (B) Mms22 foci represent sites of DSBs following CPT treatment. The majority of spontaneous GFP-Mms22 and Rad22-RFP foci do not colocalize, whereas an increased overlap in signal is observed following DNA damage. Representative images are shown. (C) Quantification of the percentage of GFP-Mms22 foci with an overlapping Rad22-RFP focus before and after CPT treatment. For each culture, foci were scored in three independent experiments and mean values were plotted with error bars representing the standard deviation of the mean.

Fission yeast nuclei are composed of two hemispherical compartments, one encompassing the nucleolus that excludes DAPI staining and is enriched with RNA and the other that stains with DAPI and contains the three chromosomes. Two chromatin protrusions containing the highly repetitive rDNA arrays extend into the nucleolus (Uzawa and Yanagida 1992). Fission yeast rDNA contains four closely spaced polar replication barriers named RFB1–4, which are sites of programmed fork pausing (Krings and Bastia 2004; Sanchez-Gorostiaga et al. 2004). As Mms22 has an important role in the recovery from drug-induced replication fork stalling, we wondered whether the protein also functions at sites of natural fork pausing, such as the rDNA repeats. To address whether Mms22 foci form exclusively at the sites of the rDNA repeats, we transformed GFP-Mms22 into cells expressing the red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged small-nucleolar-RNA-associated protein Gar1 from its endogenous locus. While GFP-Mms22 foci were frequently proximal to the Gar1-RFP signal, they were also observed at non-nucleolar sites (data not shown), suggesting that Mms22 does not function exclusively at the nucleolus.

We wanted to determine if GFP-Mms22 concentrates into foci that increase in number following DNA damage. GFP-Mms22 foci number levels varied between experiments due to the expression from the ectopic plasmid; however, in multiple independent experiments, the number of nuclei containing Mms22 foci increased two- to threefold following CPT-induced DNA damage (a representative data set is shown in Figure 5A), suggesting that Mms22 foci may represent sites of DNA damage. To address microscopically whether GFP-Mms22 foci represent sites of DSBs, we generated a strain expressing endogenous Rad22-RFP and ectopic GFP-Mms22 to assess whether the two proteins colocalize within common foci. In an asynchronous culture, the majority of Rad22-RFP and GFP-Mms22 foci did not colocalize, with only ∼5% of GFP-Mms22 foci having an overlapping Rad22-RFP focus (Figure 5, B and C). This suggests that spontaneous GFP-Mms22 foci largely do not localize to sites of HR-mediated repair, or alternatively, that Rad22-RFP and GFP-Mms22 may localize to the same sites but in a sequential manner. However, following CPT treatment, an increased association was observed, with 45% of GFP-Mms22 foci having a colocalizing Rad22-RFP signal (Figure 5, B and C), implying that at least within the limits of our microscopy system, a proportion of GFP-Mms22 foci represent sites of DSBs after CPT treatment.

Genetic interactions with HR mutants:

On the basis of the observation that Mms22 and Rad22 form largely distinct spontaneous foci, we speculated that Mms22 may act in an alternative DNA repair pathway to HR. Consequently, the elevated spontaneous Rad22 foci observed in mms22Δ cells may represent DNA damage that in the absence of Mms22 require HR for repair. To address this, we crossed mms22Δ strains with mutants defective for HR and analyzed the progeny by tetrad dissection. The mms22Δ strains that were also defective in rad22 (S.c. RAD52), rhp51 (S.c. RAD51), or rhp54 (S.c. RAD54) showed severe synthetic phenotypes. Double mutants did not arise with the expected frequency (this effect was most noted for the mms22Δ rad22Δ doubles), and when colonies did form, the double mutants showed a severe growth defect (Figure 6A). Similarly, double mms22Δ rhp57Δ (S.c. RAD57) mutants, while not as severe, showed additive growth defects and DNA damage sensitivities (Figure 6B). Taken together with the elevated numbers of Rad22 foci in mms22Δ mutants, these data suggest that, in the absence of Mms22, cells experience an elevated occurrence of spontaneous-replication-associated DNA damage that is repaired by HR.

Figure 6.—

Mms22 functions in a non-HR DNA repair pathway (A) Tetrad dissection of genetic crosses of mms22Δ and HR mutants. Representative spores from three asci are shown for each cross. (B) Synthetic additivity of mms22 and rhp57 mutations. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were exposed to the indicated DNA-damaging agent and incubated at 30° for 2–3 days.

Genetic interactions between mms22 and DNA repair mutants:

As Mms22 seems to function in a checkpoint-independent non-HR mechanism, we sought to identify other members of the pathway using genetic epistasis analysis. To this end, we performed genetic crosses to disrupt mms22Δ in strain backgrounds defective in a number of different DNA repair processes, including post-replicative repair (PRR) and replication restart.

Synergistic genetic interactions between mms22 and srs2 or rhp18 suggested that Mms22 does not function exclusively with these proteins in the PRR pathway (data not shown). Therefore, we addressed the participation of Mms22 in fork recapture and replication restart by disruption of the gene in backgrounds defective in the DNA-processing enzymes Mus81 or Rqh1. Mus81, in a complex with its partner Eme1, comprises a structure-specific endonuclease that cleaves cruciform DNA structures such as D-loops or Holliday junctions (HJs) that arise during homologous recombination (Boddy et al. 2001; Kaliraman et al. 2001; Gaillard et al. 2003; Osman et al. 2003; Whitby et al. 2003; Cromie et al. 2006; Gaskell et al. 2007). In our genetic analysis, mus81Δ mutants were as slow growing and sensitive to DNA damage and replication stress as mms22Δ mus81Δ cells, suggesting that mus81 is epistatic to mms22 with respect to growth and damage tolerance (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.—

Genetic relationship between Mms22 and other DNA repair proteins. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were exposed to the indicated DNA-damaging agent and incubated at 30° for 2–3 days.

Another class of highly conserved enzymes important for the maintenance of genomic stability is the RecQ helicase family of proteins (Bachrati and Hickson 2003). In S. pombe, the RecQ helicase Rqh1 has been shown to be required for processing of aberrant chromosome structures arising from DNA replication (Win et al. 2005). Mechanistically, RecQ-like DNA helicases can act directly to dissolve HR intermediate structures such as D-loops (Van Brabant et al. 2000), and in vitro they are capable of dissolving a DNA substrate containing two HJs into a single noncrossover product in a process termed double-junction dissolution (Wu and Hickson 2003). On the contrary to the situation with mus81, double mms22Δ rqh1Δ mutants displayed slower growth and elevated sensitivities to UV, IR, MMS, CPT, and HU compared to either mms22Δ or rqh1Δ alone, indicating that Mms22's function is important for growth in the absence of rqh1 and vice versa (Figure 7A). Together with the knowledge that mus81Δ rqh1Δ cells are inviable (Boddy et al. 2000), these data suggest that Mms22 functions with Mus81 in the repair of DNA replication fork abnormalities, and in the absence of this pathway cells require the function of Rqh1.

Finally, we examined the genetic relationship between mms22 and brc1. On the basis of putative interaction between budding yeast Mms22p and Rtt107p (Ho et al. 2002; Chin et al. 2006), we hypothesized that if mms22+ is the ortholog of MMS22, then mms22 and brc1 should show genetic epistasis if the two proteins function exclusively together. We observed that brc1Δ mutants grow with wild-type kinetics, but are sensitive to the same spectrum of DNA-damaging agents as mms22Δ, albeit at higher doses, and are not hypersensitive to IR or UV (Verkade et al. 1999; Sheedy et al. 2005; our own observations). Cells disrupted for both mms22 and brc1 showed a moderate synergistic growth defect compared to mms22Δ alone (Figure 7B), suggesting that the two proteins do not function exclusively together. Yet, taking this growth defect into account, the mms22Δ brc1Δ mutant was just as sensitive as mms22 cells to DNA damage and replication stress (Figure 7B). Together, these data suggest that Brc1 and Mms22 have some independent functions that affect cell viability; however, their functions in tolerating DNA damage during S-phase may involve a common pathway. However, it is of importance to note that brc1 mutants are still viable at these low doses of CPT (0.3 μm) and MMS (0.002%) and do not show sensitivity until exposure to higher doses (5 μm CPT and 0.01% MMS; our unpublished observations), which may result in additive sensitivity of the double mutant being undetected at these low doses.

Mms22 interacts genetically with components of the replication fork:

Together, our data suggest a role for Mms22 in the recovery from DNA damage that occurs during the process of DNA replication. As no detectable functional domains are apparent in Mms22, it seems unlikely that the protein is involved in the direct processing of abnormal replication structures. Rather, taking into account the large size of the Mms22 protein, we speculate that it might instead function as a protein interaction platform important for the restart of DNA replication after forks have paused or stalled. To address this genetically, we constructed double mutants of mms22Δ with either swi1Δ or swi3Δ. Swi1 and Swi3 form the DNA replication fork protection complex (FPC), which plays important roles in the stabilization of stalled replication forks and activation of the DNA replication checkpoint (Noguchi et al. 2004). Swi1 and Swi3 are required for fork pausing at specific sites in S. pombe (Krings and Bastia 2004), and their function is conserved in their S. cerevisiae counterparts Tof1p and Csm3p (Calzada et al. 2005). Strikingly, we observed that deletion of either swi1 or swi3 leads to a substantial rescue of the slow-growth phenotype of mms22 and also to a partial rescue of the sensitivity of mms22 mutants to MMS (Figure 8A). A slight rescue was also observed following exposure to low doses of HU and CPT, but this was not evident at doses above 2 mm and 0.3 μm, respectively.

Figure 8.—

Genetic interactions between Mms22 and components of the replication fork. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were exposed to the indicated DNA-damaging agent. Plates were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. All DNA-damaging treatments were conducted at 25°.

Another component of the traveling and paused replication fork is the checkpoint mediator Mrc1; however, unlike Swi1 and Swi3, Mrc1 is dispensable for fork pausing at a protein–DNA barrier (Calzada et al. 2005). The partial rescue of mms22Δ by swi1Δ or swi3Δ that we observed was specifically attributable to defective pausing, as deletion of Mrc1 did not improve the growth or sensitivity of mms22 mutants (Figure 8A). This suggests that Mms22 may function in the recovery of paused replication forks after they have encountered a block or obstacle.

If Mms22 has a role in the restart of replication after fork pausing or stalling, then it might follow that mms22 interacts genetically with components of the DNA replication fork. Indeed, budding yeast MMS22 was previously isolated in a screen for mutations that are synthetically lethal with the mcm10-1 allele (Araki et al. 2003). Mcm10p is an essential eukaryotic DNA replication factor, which has been shown to be required for recruitment of Cdc45p to replication origins (Sawyer et al. 2004) and for the stabilization and targeting of DNA polymerase α (Polα) to chromatin (Fien et al. 2004; Ricke and Bielinsky 2004). To establish whether mms22+ displays interactions analogous to MMS22, we disrupted mms22+ in a DNA replication-defective background using a hypomorphic mutation in cdc23, the fission yeast homolog of MCM10.

The cdc23-M36 allele was isolated as an S-phase-defective temperature-sensitive mutant, which arrested with a cdc phenotype at the restrictive temperature of 36°, but is viable at the intermediate temperature of 30° (Nasmyth and Nurse 1981). At the permissive temperature of 25°, the double cdc23-M36 mms22Δ mutant was viable, with a slight growth defect and elevated sensitivity to damage (Figure 8B). Moreover, the restrictive temperature of cdc23-M36 was reduced to 30° in an mms22Δ background (Figure 8B), with the cells displaying an aberrant and elongated terminal morphology. Therefore, similarly to the situation for mms22 and mcm10 in budding yeast, deletion of mms22+ shows a synthetic additive interaction with cdc23 when grown at the semipermissive temperature.

As mms22 displays a synthetic interaction with mcm10, we generated mms22Δ strains carrying defective DNA polymerase alleles to address whether Mms22 also has roles in coordinating elongation of DNA synthesis. Polα–primase is the only enzyme capable of initiating de novo DNA synthesis (Burgers 1998) and is required for the initiation of DNA synthesis on the leading and lagging strand (Waga and Stillman 1998). We generated mms22Δ strains carrying the pol1-1 mutation in the catalytic subunit of Polα. pol1-1 thermosensitive mutants are defective in DNA synthesis and arrest with a cdc phenotype in late S-phase at the restrictive temperature (D'Urso et al. 1995; Murakami and Okayama 1995). In line with the interaction between mcm10 and mms22, at 25° the double mutant was viable with a slight synergistic growth defect and sensitivity to DNA damage (Figure 8B). However, at 30°, which permits growth of the pol1-1 hypomorph, the mms22Δ pol1-1 mutant did not form colonies (Figure 8B). We found the same interaction with another thermosensitive mutant of the catalytic subunit of Polα, swi7-H4, confirming that the additivity is not specific to the pol1-1 allele (data not shown).

To further explore the link between mms22 and components of the replication fork, we examined genetic interactions with the replicative polymerases δ and ε. Like Polα, Polδ and Polε are both multi-subunit, essential enzymes, but the precise roles of the two polymerases in DNA elongation are controversial (reviewed in Garg and Burgers 2005). We utilized thermosensitive alleles of the catalytic subunits of Polε (cdc20-M10) and Polδ (cdc6-23) to address interactions with both polymerases.

Curiously, the cdc6-23 allele of Polδ improved the growth of mms22Δ at 25°, which was also evident in response to DNA-damaging treatments (Figure 9A). Conversely, at the semipermissive temperature of 30°, the mms22Δ cdc6-23 displayed a synergistic growth defect compared to parental strains (Figure 9A). The same trend was observed with cdc27-K3 (data not shown), an allele of a Polδ subunit that is required for full polymerase processivity (Zuo et al. 2000). This opposing effect was not observed when introducing the Polε cdc20-M10 allele into the mms22 background. No additivity was observed at 30° (Figure 9B) and growth was not drastically improved at 25° (Figure 9B). While we cannot rule out a requirement for Mms22 function in processing DNA damage that arises due to the DNA polymerase mutations, the genetic interactions suggest that the function of Mms22 in replication restart may be mediated at the replication fork.

Figure 9.—

Genetic interactions between Mms22 and DNA polymerases δ and ɛ. Fivefold serial dilutions of cells were exposed to the indicated DNA damaging agent. Plates were incubated at the indicated temperatures for 2–4 days. All DNA-damaging treatments were conducted at 25°.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we present the identification of the novel gene mms22+ that is important for the recovery from S-phase-associated DNA damage in S. pombe. A lack of Mms22 protein results in elevated DNA damage specifically in the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle. While we assume that this indicates that damage occurs during these stages, we cannot rule out the possibility of the lesions actually arising during another phase, such as mitosis. Moreover, loss of Mms22 function leads to elevated genomic instability as judged by increased minichromosome loss. We demonstrate through a series of genetic analyses that Mms22 likely functions in a pathway important for the processing of abnormal structures that arise in S-phase involving the proposed HJ resolvase Mus81-Eme1 and that loss of Mms22 function requires an intact HR pathway for full viability. On the basis of genetic interactions with thermosensitive alleles of essential DNA replication factors, we propose that Mms22 carries out its function in replication restart after stalling directly at the replication fork.

The role of Mms22 following DNA damage:

As an epistatic relationship between two genes is classically interpreted as an involvement of the gene products in a common pathway, the synthetic interactions between mms22 and many homologous recombination genes in the absence of exogenous DNA damage suggests that Mms22 is unlikely to participate in such a pathway, at least not exclusively. In agreement with this, the DNA damage sensitivity conferred by the mms22 deletion is synergistic with that resulting from deletion of rhp57 (Figure 6B). By these criteria, it would appear that mms22+ is required for a pathway of spontaneous and MMS-, UV-, and CPT-induced damage recovery that is not exclusively mediated through Rhp51-dependent recombination.

The elevated numbers of S- and G2-phase-associated Rad22 foci, taken together with the requirement for HR in the absence of Mms22 function, suggests that mms22 mutants experience an elevated occurrence of spontaneous DNA damage that needs HR for repair. Deletion of Chk1 did not negatively impact on the growth of the mms22 strain (Figure 3A), suggesting that the Chk1-dependent cell cycle delay caused by mms22Δ is not due to elevated DSBs in the mms22 background. Furthermore, mus81Δ cells are hypersensitive to CPT and yet mus81Δ has no genetic interaction with mms22Δ, suggesting that loss of Mms22 function does not lead to broken forks. Instead, the increased Rad22 foci may be indicative of exposed ssDNA regions arising during S-phase due to uncoupling of leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at stalled or paused replication forks (Branzei and Foiani 2007). It will be of interest to determine the exact structure(s) that accumulate in the absence of Mms22, which may help to clarify the role in plays in the prevention of genomic instability. Genetic data suggest that mms22 and mus81 probably function together in the repair of abnormal DNA structures. The two mutants are epistatic during unperturbed growth and also in terms of HU-, CPT-, and MMS-induced damage sensitivities and also share common genetic interactions with other repair factors. Rqh1 is essential for viability in strains that lack either Mus81-Eme1 or Slx1-Slx4 (Boddy et al. 2001; Coulon et al. 2004) and in strains that lack the Swi1-Swi3 FPC complex (Noguchi et al. 2003; Coulon et al. 2004). While we did not observe a synthetic lethal interaction between rqh1 and mms22, the double mutant did have a severe synergistic growth defect. Also, we have observed that deletion of Slx1 does not negatively impact on the growth of mms22Δ strains or on their survival following damage (C. L. Dovey and P. Russell, unpublished data). The knowledge that rqh1 rhp51 double mutants are viable (Murray et al. 1997) supports our hypothesis that Mms22 acts in a pathway involving the structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1 (and possibly Slx1-Slx4), which is distinct from Rqh1 and Rhp51.

The Rhp51 mediators Swi5/Sfr1 and Rhp55/57 are not exclusively redundant and may process DSBs differently (Akamatsu et al. 2007). Mus81-Eme1 has been suggested to function in the Swi5-dependent pathway of HR repair, and depending on the DNA substrate, Swi5 can generate either Mus81-dependent crossovers or Mus81-independent noncrossovers (Hope et al. 2007). It will interesting to determine the specific substrates that require Mms22 for repair and how these are channeled into alternative repair pathways in its absence. The phenotypes of mms22Δ are similar, but not as severe as those of mus81Δ; therefore, we propose that Mus81 has Mms22-independent functions. In line with this, while Mus81 is required for the production of viable spores in meiosis (Boddy et al. 2001), there is no such requirement for Mms22 (data not shown).

The function of Mms22 at the replication fork:

The Swi1-Swi3 FPC promotes the stabilization of replication forks and on fork stalling is required for effective Cds1 activation (Noguchi et al. 2004). Fork pausing at the MAT locus imprinting site and replication termination at RTS1 are dependent on Swi1 and Swi3 (Dalgaard and Klar 2000). Like the FPC, Mrc1 similarly travels with replication forks (Katou et al. 2003; Osborn and Elledge 2003) and mediates the activation of Cds1 on stalling (Tanaka and Russell 2004). Mrc1 phosphorylation also contributes to the stability of stalled replication forks (Katou et al. 2003; Osborn and Elledge 2003); however, in a system for studying transient pausing of DNA replication forks at a protein–DNA barrier in budding yeast, fork pausing depended on Tof1p and Csm3p, but not on Mrc1p (Calzada et al. 2005). Similarly, fork stalling at the rDNA RFB actively requires Tof1p, but not Mrc1p (Tourriere et al. 2005). In this study, we observed that deletion of the Swi1-Swi3 FPC, but not of Mrc1, partially rescued the phenotypes of a mms22 mutant. This suggests that, in the absence of Mms22, restart of replication after fork pausing is defective, and consequently by eliminating Swi1-Swi3-mediated pausing, Mms22 becomes less important for viability in unperturbed conditions and following DNA damage by agents that physically stall the progression of the replication fork.

If Mms22 functions in replication restart directly at the replisome, one would predict mms22 to interact genetically with other components required for the resumption of DNA synthesis. Indeed, mms22 shows synthetic additivity with cdc23 (mcm10) and polα at the semipermissive temperature of 30°. While double mutants of mms22 and cdc23 or polα are viable at 25°, the phenotypes of mms22Δ are enhanced by the polα thermosensitive mutations. However, we observed different genetic interactions with alleles of the replicative polymerases Polδ and Polε. At 25°, defective polδ actually improved the growth and damage tolerance of mms22 strains (Figure 9B), whereas at 30° the double mms22 polδ grew less well than mms22 or polδ alone. These interactions were not observed with polε. These data may be explained if Mms22 functions in response to DNA structures that are generated specifically by the Polδ-associated replisome. In cdc6-23 or cdc27-K3 strains, Polε may be able to substitute for defective Polδ, alleviating the cellular need for Mms22 to process aberrant replication structures. However, the absence of Mms22 under conditions of dysfunctional Polδ at 30° results in the cellular burden exceeding the threshold for viability, leading to a synthetic interaction. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that mutants of DNA Polα and Polδ, but not of Polε, accumulate HJs in the rDNA repeats (Zou and Rothstein 1997), which is consistent with our proposed role for Mms22 in the processing of aberrant DNA structures that arise at replication forks. As Mms22 foci increase in response to damage, it is likely that Mms22 functions directly on chromatin, most likely at broken or stalled replication forks. It will be important to determine the mechanisms by which this recruitment occurs and its functional consequences.

Identification of Mms22 as a homolog of budding yeast MMS22:

We identified mms22+ as a putative homolog of MMS22 on the basis of its regions of sequence similarity to budding yeast Mms22p (Figure 1A). Similarly to HR mutants, budding yeast mms22 strains are hypersensitive to topoisomerase II-generated DNA damage (Baldwin et al. 2005); however, Mms22p has been placed in a novel pathway for repair, distinct from HR due to synergistic genetic interactions with rad51, rad52, and rad54 (Araki et al. 2003; Baldwin et al. 2005). We report that mms22 mutants show synthetic growth defects with rad22, rhp51, rhp54, and also with rhp57, suggesting that fission yeast Mms22 also probably acts within a pathway distinctive to single-strand invasion. However, the frequency of etoposide-induced HR in budding yeast mms22 cells is reduced, arguing against the two pathways being simply an alternative to each other and instead suggesting that, although separate, the pathways must be linked (Baldwin et al. 2005). S. pombe Mms22 may function analogously to convert aberrant DNA structures into a form that can be subsequently resolved by another repair pathway.

Budding yeast Mms22p interacts with the cullin Rtt101p and also with Rtt107p (Ho et al. 2002). Rtt107p functions in the restart of replication after damage and has been proposed to modulate the function of proteins that are required for DNA synthesis resumption (Chin et al. 2006). Similarly, Rtt101p promotes fork progression through DNA lesions or naturally occurring protein–DNA pause sites (Luke et al. 2006). On the basis of these and other studies, the proteins have been placed along with Mms1p, another protein required for the repair of replication-dependent damage, in a common DNA repair epistasis group with Mms1p functioning upstream of Mms22p in a sequential pathway (Araki et al. 2003). Despite this, previous genetic data suggested that Mms1p and Mms22p might also have distinct functions. Disruption of the HR genes RAD51 or RAD52 in a mms1 background was reported to not result in a synergistic growth defect (Hryciw et al. 2002; Araki et al. 2003), unlike disruption of MMS22 in a rad51 or rad52 mutant background (Araki et al. 2003), which suggested that Mms22p may have non-HR repair functions that are independent of Mms1p despite its location within the same epistasis group. However, recent large-scale studies have uncovered synthetic interactions between HR genes and both mms1 and mms22 (Pan et al. 2006; Collins et al. 2007). Despite these conflicting studies, the potential for genetic variation among individual members of an epistasis group may explain why in S. pombe we found that double mms22 brc1 mutants showed a modestly enhanced growth defect compared to mms22 alone (Figure 7B).

Thus, Mms22 and Brc1 may have independent functions, or alternatively the functions of the individual members of the S. cerevisiae MMS22 complex may not be completely conserved in S. pombe, resulting in differing genetic relationships. In support of this, S. cerevisiae Rtt107p function has been shown to be partially independent of HR in response to MMS (Chin et al. 2006), whereas fission yeast brc1 rhp51 double mutants display sensitivity similar to the single mutants, suggesting that Brc1 acts in the same pathway as Rhp51 for repair of MMS-induced damage (Sheedy et al. 2005; our unpublished data). Therefore, while we have no definitive evidence that Mms22 is the true functional homolog of Mms22p, our initial genetic characterization does not dispute this. Further, ongoing investigations into the function of Mms22 should shed more light on the role of this new protein in DNA repair and on whether a functional Mms22p-like complex exists in fission yeast.

Taking all of our data into consideration, we propose the following model for Mms22 function during the coordination of leading- and lagging-strand replication at sites of stalled replication or in lagging-strand synthesis following restart. In response to a fork-blocking lesion on the DNA template, the Swi1-Swi3 FPC complex mediates Polδ-associated replisome stalling. Mms22, possibly in a complex with Brc1, associates with the stalled replisome and may act either to facilitate processing by repair factors such as Mus81-Eme1 or, alternatively, to block the action of other repair pathways such as HR. In the absence of Mms22, damage-induced toxic structures are generated at the replication fork, leading to an increased requirement for processing by HR and the helicase Rqh1. Under these conditions, replication restart depends on the optimal function of the replisome, as defects in cdc23 and Polα are deleterious in the absence of Mms22. The phenotypes of mms22 mutants can be partially rescued by deletion of the Swi1-Swi3 FPC, which alleviates the need for Mms22-mediated repair by destabilizing the fork and permitting direct processing by other repair pathways such as HR.

Finally, we note that an independent study of S. pombe Mms22 appeared while this article was in preparation (Yokoyama et al. 2007). In agreement with the findings reported here, Yokoyama et al. (2007) found that Mms22, which they termed Mus7, is involved in the repair of replication-associated DNA damage in a pathway likely involving Mus81. The authors found that the rate of spontaneous Rhp51-dependent gene conversion was reduced in mus7Δ cells, despite the accumulation of Rad22-YFP foci, suggesting that Mus7 functions downstream of Rad22 in the Rhp51-dependent conversion-type recombination pathway. Finally, Yokoyama et al. (2007) noted that fission yeast mus7 cells share many phenotypes with budding yeast mms1 mutants and they therefore proposed that Mus7 and Mms1p might be functional homologs whose sequences have diverged beyond recognition (Yokoyama et al. 2007). The phenotypes of budding yeast Mms1p and Mms22p mutants are very similar and are consistent with the phenotype that arises on loss of fission yeast Mus7/Mms22. However, our discovery of Mms22 through it sequence similarity specifically to Mms22p suggests that it is more likely that Mus7/Mms22 is an ortholog of Mms22p.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charly Chahwan for the initial identification of S. pombe mms22+ and for helpful suggestions throughout the course of this study. We thank John Prudden and Tim Humphrey (JP970), Victoria Martin (VM166, VM257), and Yoshiki Yamada (YY218) for strains, as well as Oliver Limbo for strains OL4087 and OL4088 and the pRep41-N-GFP-mms22+ plasmid. Members of the Russell lab and the Cell Cycle Groups at The Scripps Research Institute are thanked, particularly Yoshiki Yamada, Li-Lin Du, Jessica Williams, and M. Nick Boddy for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript. This research was funded by National Institutes of Health grant GM59447 awarded to P.R.

References

- Akamatsu, Y., Y. Tsutsui, T. Morishita, M. S. Siddique, Y. Kurokawa et al., 2007. Fission yeast Swi5/Sfr1 and Rhp55/Rhp57 differentially regulate Rhp51-dependent recombination outcomes. EMBO J. 26: 1352–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire, R. C., E. R. Nimmo, K. Ekwall, J.-P. Javerzat and G. Granston, 1995. Mutations derepressing silent centromeric domains in fission yeast disrupt chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 9: 218–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang et al., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki, Y., Y. Kawasaki, H. Sasanuma, B. K. Tye and A. Sugino, 2003. Budding yeast mcm10/dna43 mutant requires a novel repair pathway for viability. Genes Cells 8: 465–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrati, C. Z., and I. D. Hickson, 2003. RecQ helicases: suppressors of tumorigenesis and premature aging. Biochem. J. 374: 577–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler, J., J. Q. Wu, M. S. Longtine, N. G. Shah, A. McKenzie et al., 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14: 943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, E. L., A. C. Berger, A. H. Corbett and N. Osheroff, 2005. Mms22p protects Saccharomyces cerevisiae from DNA damage induced by topoisomerase II. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 1021–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, C. B., L. K. Lewis, G. Karthikeyan, K. S. Lobachev, Y. H. Jin et al., 2001. Genes required for ionizing radiation resistance in yeast. Nat. Genet. 29: 426–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, M. N., and P. Russell, 2001. DNA replication checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 11: R953–R956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, M. N., A. Lopez-Girona, P. Shanahan, H. Interthal, W. D. Heyer et al., 2000. Damage tolerance protein Mus81 associates with the FHA1 domain of checkpoint kinase Cds1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 8758–8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, M. N., P. H. Gaillard, W. H. McDonald, P. Shanahan, J. R. Yates, III et al., 2001. Mus81-Eme1 are essential components of a Holliday junction resolvase. Cell 107: 537–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei, D., and M. Foiani, 2007. Interplay of replication checkpoints and repair proteins at stalled replication forks. DNA Repair 6: 944–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers, P. M., 1998. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases in DNA replication and DNA repair. Chromosoma 107: 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, A., B. Hodgson, M. Kanemaki, A. Bueno and K. Labib, 2005. Molecular anatomy and regulation of a stable replisome at a paused eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Genes Dev. 19: 1905–1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M., M. Bellaoui, C. Boone and G. W. Brown, 2002. A genome-wide screen for methyl methanesulfonate-sensitive mutants reveals genes required for S phase progression in the presence of DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 16934–16939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin, J. K., V. I. Bashkirov, W. D. Heyer and F. E. Romesberg, 2006. Esc4/Rtt107 and the control of recombination during replication. DNA Repair 5: 618–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S. R., K. M. Miller, N. L. Maas, A. Roguev, J. Fillingham et al., 2007. Functional dissection of protein complexes involved in yeast chromosome biology using a genetic interaction map. Nature 446: 806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulon, S., P. H. Gaillard, C. Chahwan, W. H. McDonald, J. R. Yates, III et al., 2004. Slx1-Slx4 are subunits of a structure-specific endonuclease that maintains ribosomal DNA in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromie, G. A., R. W. Hyppa, A. F. Taylor, K. Zakharyevich, N. Hunter et al., 2006. Single Holliday junctions are intermediates of meiotic recombination. Cell 127: 1167–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, J. Z., and A. J. Klar, 2000. swi1 and swi3 perform imprinting, pausing, and termination of DNA replication in S. pombe. Cell 102: 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, L. L., T. M. Nakamura, B. A. Moser and P. Russell, 2003. Retention but not recruitment of Crb2 at double-strand breaks requires Rad1 and Rad3 complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 6150–6158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Urso, G., B. Grallert and P. Nurse, 1995. DNA polymerase alpha, a component of the replication initiation complex, is essential for the checkpoint coupling S phase to mitosis in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 108: 3109–3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fien, K., Y. S. Cho, J. K. Lee, S. Raychaudhuri, I. Tappin et al., 2004. Primer utilization by DNA polymerase α-primase is influenced by its interaction with Mcm10p. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 16144–16153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard, P. H., E. Noguchi, P. Shanahan and P. Russell, 2003. The endogenous Mus81-Eme1 complex resolves Holliday junctions by a nick and counternick mechanism. Mol. Cell 12: 747–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg, P., and P. M. J. Burgers, 2005. DNA polymerases that propagate the eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 40: 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell, L. J., F. Osman, R. J. Gilbert and M. C. Whitby, 2007. Mus81 cleavage of Holliday junctions: A failsafe for processing meiotic recombination intermediates? EMBO J. 26: 1891–1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, S. H., D. M. Sheedy, A. R. Cuddihy and M. J. O'Connell, 2004. Coordination of DNA damage responses via the Smc5/Smc6 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 662–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y., A. Gruhler, A. Heilbut, G. D. Bader, L. Moore et al., 2002. Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415: 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope, J. C., L. D. Cruzata, A. Duvshani, J. Mitsumoto, M. Maftahi et al., 2007. Mus81-Eme1-dependent and-independent crossovers form in mitotic cells during double strand break repair in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 3828–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hryciw, T., M. Tang, T. Fontanie and W. Xiao, 2002. MMS1 protects against replication-dependent DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266: 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jowsey, P. A., A. J. Doherty and J. Rouse, 2004 Human PTIP facilitates ATM-mediated activation of p53 and promotes cellular resistance to ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 55562–55569. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaliraman, V., J. R. Mullen, W. M. Fricke, S. A. Bastin-Shanower and S. J. Brill, 2001. Functional overlap between Sgs1-Top3 and the Mms4-Mus81 endonuclease. Genes Dev. 15: 2730–2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou, Y., Y. Kanoh, M. Bando, H. Noguchi, H. Tanaka et al., 2003. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature 424: 1078–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krings, G., and D. Bastia, 2004. swi1- and swi3-dependent and independent replication fork arrest at the ribosomal DNA of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 14085–14090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., S. Nizza, T. Hayes, K. Bass, A. Irmish et al., 2007. Brc1-mediated rescue of Smc5/6 deficiency: requirement for multiple nucleases and a novel Rad18 function. Genetics 175: 1585–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, A. R., M. Walicka, D. J. Griffiths, J. M. Murray, F. Z. Watts et al., 1995. The rad18 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe defines a new subgroup of the SMC superfamily involved in DNA repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 7067–7080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisby, M., J. H. Barlow, R. C. Burgess and R. Rothstein, 2004. Choreography of the DNA damage response: spatiotemporal relationships among checkpoint and repair proteins. Cell 118: 699–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke, B., G. Versini, M. Jaquenoud, I. W. Zaidi, T. Kurz et al., 2006. The cullin Rtt101p promotes replication fork progression through damaged DNA and natural pause sites. Curr. Biol. 16: 786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, W. H., Y. Pavlova, J. R. Yates, III and M. N. Boddy, 2003. Novel essential DNA repair proteins Nse1 and Nse2 are subunits of the fission yeast Smc5-Smc6 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 45460–45467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., A. Klar and P. Nurse, 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194: 795–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, H., and H. Okayama, 1995. A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature 374: 817–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J. M., H. D. Lindsay, C. A. Munday and A. M. Carr, 1997. Role of Schizosaccharomyces pombe RecQ homolog, recombination, and checkpoint genes in UV damage tolerance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 6868–6875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T. M., L. L. Du, C. Redon and P. Russell, 2004. Histone H2A phosphorylation controls Crb2 recruitment at DNA breaks, maintains checkpoint arrest, and influences DNA repair in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 6215–6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth, K., and P. Nurse, 1981. Cell division cycle mutants altered in DNA replication and mitosis in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Gen. Genet. 182: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, O., T. Matsumoto and M. Yanagida, 1986. Construction of a mini-chromosome by deletion and its mitotic and meiotic behaviour in fission yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 203: 397–405. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, E., C. Noguchi, L. L. Du and P. Russell, 2003. Swi1 prevents replication fork collapse and controls checkpoint kinase Cds1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 7861–7874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, E., C. Noguchi, W. H. McDonald, J. R. Yates, III and P. Russell, 2004. Swi1 and Swi3 are components of a replication fork protection complex in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 8342–8355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, A. J., and S. J. Elledge, 2003. Mrc1 is a replication fork component whose phosphorylation in response to DNA replication stress activates Rad53. Genes Dev. 17: 1755–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, F., J. Dixon, C. L. Doe and M. C. Whitby, 2003. 2003 Generating crossovers by resolution of nicked Holliday junctions: a role for Mus81-Eme1 in meiosis. Mol. Cell 12: 761–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., P. Ye, D. S. Yuan, X. Wang, J. S. Bader et al., 2006. A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 124: 1069–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebernard, S., W. H. McDonald, Y. Pavlova, J. R. Yates, III and M. N. Boddy, 2004. Nse1, Nse2, and a novel subunit of the Smc5-Smc6 complex, Nse3, play a crucial role in meiosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 4866–4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebernard, S., J. Wohlschlegel, W. H. McDonald, J. R. Yates, III and M. N. Boddy, 2006. The Nse5-Nse6 dimer mediates DNA repair roles of the Smc5-Smc6 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26: 1617–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pommier, Y., 2006. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6: 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudden, J., J. S. Evans, S. P. Hussey, B. Deans, P. O'Neill et al., 2003. Pathway utilization in response to a site-specific DNA double-strand break in fission yeast. EMBO J. 22: 1419–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricke, R. M., and A. K. Bielinsky, 2004. Mcm10 regulates the stability and chromatin association of DNA polymerase-α. Mol. Cell 16: 173–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T. M., M. S. Kobor, S. A. Bastin-Shanower, M. Ii, S. A. Horte et al., 2006. Slx4 regulates DNA damage checkpoint-dependent phosphorylation of the BRCT domain protein Rtt107/Esc4. Mol. Biol. Cell 17: 539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J., 2004. Esc4p, a new target of Mec1p (ATR), promotes resumption of DNA synthesis after DNA damage. EMBO J. 23: 1188–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gorostiaga, A., C. Lopez-Estrano, D. B. Krimer, J. B. Schvartzman and P. Hernandez, 2004. Transcription termination factor reb1p causes two replication fork barriers at its cognate sites in fission yeast ribosomal DNA in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 398–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, S. L., I. H. Cheng, W. Chai and B. K. Tye, 2004. Mcm10 and Cdc45 cooperate in origin activation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 340: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, A. A., L. Aravind, T. L. Madden, S. Shavirin, J. L. Spouge et al., 2001. Improving the accuracy of PSI-BLAST protein database searches with composition-based statistics and other refinements. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2994–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheedy, D. M., D. Dimitrova, J. K. Rankin, K. L. Bass, K. M. Lee et al., 2005. Brc1-mediated DNA repair and damage tolerance. Genetics 171: 457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K., and P. Russell, 2004. Cds1 phosphorylation by Rad3-Rad26 kinase is mediated by forkhead-associated domain interaction with Mrc1. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 32079–32086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourriere, H., G. Versini, V. Cordon-Preciado, C. Alabert and P. Pasero, 2005. Mrc1 and Tof1 promote replication fork progression and recovery independently of Rad53. Mol. Cell 19: 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzawa, S., and M. Yanagida, 1992. Visualization of centromeric and nucleolar DNA in fission yeast by fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Cell Sci. 101: 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brabant, A. J., T. Ye, M. Sanz, J. L. German, III, N. A. Ellis et al., 2000. Binding and melting of D-loops by the Bloom syndrome helicase. Biochemistry 39: 14617–14625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkade, H. M., S. J. Bugg, H. D. Lindsay, A. M. Carr and M. J. O'Connell, 1999. Rad18 is required for DNA repair and checkpoint responses in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 2905–2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waga, S., and B. Stillman, 1998. The DNA replication fork in eukaryotic cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67: 721–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J. F., 1988. DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: identities, mechanisms of formation, and reparability. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 35: 95–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitby, M. C., F. Osman and J. Dixon, 2003. Cleavage of model replication forks by fission yeast Mus81-Eme1 and budding yeast Mus81-Mms4. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 6928–6935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win, T. Z., H. W. Mankouri, I. D. Hickson and S. W. Wang, 2005. A role for the fission yeast Rqh1 helicase in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Sci. 118: 5777–5784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L., and I. D. Hickson, 2003. The Bloom's syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature 426: 870–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama, M., H. Inoue, C. Ishii and Y. Murakami, 2007. The novel gene mus7+ is involved in the repair of replication-associated DNA damage in fission yeast. DNA Repair 6: 770–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H., and R. Rothstein, 1997. Holliday junctions accumulate in replication mutants via a RecA homolog-independent mechanism. Cell 90: 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, S., V. Bermudez, G. Zhang, Z. Kelman and J. Hurwitz, 2000. Structure and activity associated with multiple forms of Schizosaccharomyces pombe DNA polymerase delta. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 5153–5162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]