Abstract

Background and purpose:

There is little information about the excitatory cholinergic mechanisms of mouse small intestine although this model is important for gene knock-out studies.

Experimental approach:

Using patch-clamp techniques, voltage-dependent and pharmacological properties of carbachol- or intracellular GTPγS-activated cationic channels in mouse ileal myocytes were investigated.

Key results:

Three types of cation channels were identified in outside-out patches (17, 70 and 140 pS). The voltage-dependent behaviour of the 70 pS channel, which was also the most abundantly expressed channel (∼0.35 μ−2) was most consistent with the properties of the whole-cell muscarinic current (half-maximal activation at −72.3±9.3 mV, slope of −9.1±7.4 mV and mean open probability of 0.16±0.01 at −40 mV; at near maximal activation by 50 μM carbachol). Both channel conductance and open probability depended on the permeant cation in the order: Cs+ (70 pS) >Rb+ (66pS) >Na+ (47 pS) >Li+ (30 pS). External application of divalent cations, quinine, SK&F 96365 or La3+ strongly inhibited the whole-cell current. At the single channel level the nature of the inhibitory effects appeared to be very different. Either reduction of the open probability (quinine and to some extent SK&F 96365 and La3+) or of unitary current amplitude (Ca2+, Mg2+, SK&F 96365, La3+) was observed implying significant differences in the dissociation rates of the blockers.

Conclusions and implications:

The muscarinic cation current of murine small intestine is very similar to that in guinea-pig myocytes and murine genetic manipulation should yield important information about muscarinic receptor transduction mechanisms.

Keywords: cation channel, muscarinic receptor, carbachol, ileal smooth muscle, mouse small intestine

Introduction

Activation of muscarinic receptor-gated cationic channels in mammalian gastrointestinal smooth muscle is an important process underlying neuromuscular synaptic transmission and contraction, which involves activation of G-proteins, phospholipase C (PLC) and, finally, increased intracellular calcium concentration. Currently these mechanisms have been best evaluated in guinea-pig longitudinal ileal smooth muscle myocytes. However, the properties of the gastrointestinal smooth muscles could differ significantly depending on the species and gut region. Even within related classes of species (e.g. rodents) substantial differences in the electrophysiological properties of the same gastrointestinal regions have been found (Kuriyama et al., 1998).

Although the classical model for the investigation of the muscarinic receptor-mediated cation current in the small intestine has been the guinea-pig ileum (Inoue and Isenberg, 1990a; Zholos and Bolton, 1994; Bolton and Zholos, 1997) in the past few years there has been an increasing trend towards electrophysiological studies using genetically modified mice as a novel model offering the advantage of selective knockout or manipulation of certain genes (Kostenis et al., 1997; Gomeza et al., 1999; Stengel et al., 2000; Bymaster et al., 2001; Yamada et al., 2001; So et al., 2005). Thus, in the present study we investigated the properties of the muscarinic receptor-stimulated single cationic channels (MRCC) in murine ileal smooth muscle cells. In our previous electrophysiological studies performed using myocytes isolated from the guinea-pig ileum three types of nonselective cationic channels with distinct properties were identified (Zholos et al., 2004; Dresvyannikov et al., 2004). We found that the 60 pS (e.g., medium conductance) channel mainly carried the whole-cell current and had a U-shaped mean patch current–voltage (I–V) relationship at negative potentials and a reversal potential (Erev) close to 0 mV.

However, the molecular nature of the three types of MRCC remains unknown although it has been recently reported that transient receptor potential TRPC4−/− mouse gastric myocytes are lacking MRCC current (Lee et al., 2005). These new findings raise important questions of identification by characterizing the native channel(s) underlying the muscarinic cation current in mouse gastrointestinal smooth muscle cells so that they can be compared with the properties of heterologously expressed TRPC4/5 channel proteins. Thus, our present study examines the single channel(s) underlying carbachol (CCh)-mediated excitation in murine longitudinal ileal myocytes and evaluates their main electrophysiological and pharmacological properties. Our present results should allow a rigorous analysis of the molecular nature of the channel, with TRP knockout mice.

Some of these results have been presented in an abstract form (Dresvyannikov et al., 2005).

Methods

Cell preparation and current recordings

Single smooth muscle myocytes were enzymatically isolated from the longitudinal muscle layer of the mouse ileum as described previously (Zholos and Bolton, 1995; Dresvyannikov et al., 2003, 2004). Briefly, adult wild-type (WT) mice of either sex weighing 25–30 g were humanely killed by dislocation of the neck. The longitudinal muscle layer from the ileum was dissected and cut into small pieces of 1–3 mm in size. For cell dispersion, the tissue segments were treated with collagenase (1 mg/ml, type 1A or XI) at 37°C for 15–17 min.

Membrane current recordings were made using the whole-cell and outside-out patch configurations of the tight-seal recording techniques at room temperature with borosilicate patch pipettes of 2–4 MΩ resistance using an Axopatch 200B (Molecular Devices, USA) voltage-clamp amplifier. Voltage-clamp pulses were generated and data were captured using a Digidata 1322A interfaced to a computer running the pClamp program (Molecular Devices, USA). Currents were filtered at 1 or 2 kHz and sampled at 5 or 10 kHz in whole-cell and single channel recordings, respectively. For illustrations, single channel recordings were digitally filtered (500 Hz lowpass Gaussian filter) and resampled at 1 kHz. Muscarinic cation current was activated by adding carbachol (50 μM) to the external solution or guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) (200 μM) to the pipette solution. Outside-out patches were obtained by pulling the pipette away from the cell after maximum CCh- or GTPγS-evoked current had developed.

Solutions

The external solution (A) in which cationic current was recorded consisted of (in mM): CsCl 120, glucose 12, N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES) 10, pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH (total Cs+ 124 mM). Pipettes were filled with the following solution (B) (in mM): CsCl 80, adenosine 5′ triphosphate magnesium salt (ATP) 1, creatine 5, guanosine 5′-triphosphate lithium salt (GTP) 1, D-glucose 5, HEPES 10, 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) 10, CaCl2 4.6 ([Ca2+]i clamped at 100 nM), pH adjusted to 7.4 with CsOH (total Cs+ 124 mM). Before the beginning of the experiment myocytes were kept in the following solution (in mM): NaCl 120, KCl 6, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, glucose 12, HEPES 10, pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH.

Measurement and data analysis

Data were analysed and plotted using the pClamp (Molecular Devices, USA) and MicroCal Origin software (MicroCal Software Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). The current–voltage (I–V) relationship was obtained by applying a slow 6 s duration voltage ramp from 80 to −120 mV before and after carbachol application with an off-line correction for the background current. Single channel events were identified on the basis of the half-amplitude threshold-crossing criterion. Values are given as the means±s.e.m.; n represents the number of measurements. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05.

Materials

Collagenase (type 1A or XI), ATP, GTP, GTPγS, HEPES, BAPTA, carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol), quinine and 1-[β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]-4-methoxyphenethyl]-1H-imidazole·HCl (SK&F 96365) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (Poole, Dorset, UK).

Results

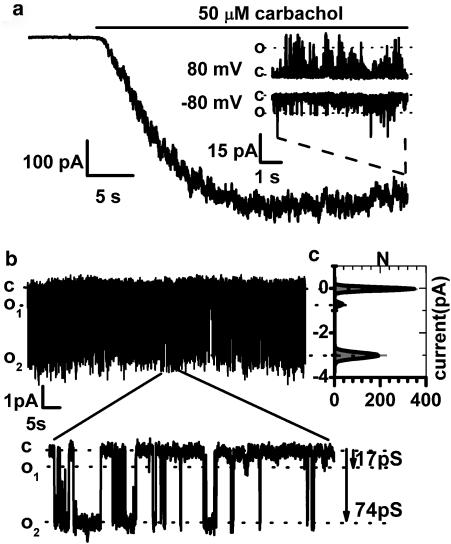

External application of CCh (50 μM) or internal GTPγS (200 μM) in symmetrical Cs+ solutions at −40 mV caused an inward current with a peak amplitude of 598±48 pA (n=71). A representative example of the muscarinic cation current activation is shown in (Figure 1a). The I–V relationship of the whole-cell current was U-shaped at negative potentials and Erev was close to 0 mV (for example, Figure 2e, inset), similar to its counterpart in guinea-pig ileal myocytes. Outside-out patch excision at maximal response to carbachol revealed activity of three types of cationic channels with unitary conductance of 16.5±1.1 pS (n=12), 69.0±0.9 pS (n=37) and 141±9 pS (n=4) (Figure 1a,b). These values roughly corresponded to the 10, 60 and 130 pS conductance cation channels which we have previously identified in guinea-pig myocytes (Zholos et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Representative whole-cell cation current response to 50 μM carbachol application (a) recorded at −40 mV. Examples of the 140 pS channel activity at −80 and 80 mV in an outside-out membrane patch, formed at the maximal whole-cell response to the agonist are shown in the inset. In a membrane patch from a different cell (b) activity of 17 and 74 pS MRCC is evident; see also the all-point amplitude histogram shown in (c). The dotted lines in all figures indicate the current levels corresponding to the open (O) and closed (C) channel states. Holding potential was −40 mV. Calculated current amplitudes and open probabilities were −0.72±0.09 pA, Po=0.03 and −2.98±0.14 pA, Po=0.24 for the small and medium conductance channels, respectively.

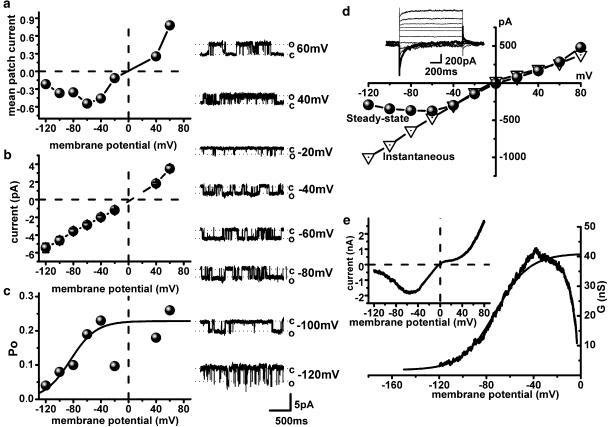

Figure 2.

Voltage dependence of gating of the medium conductance channel (a, b and c) determines CCh-evoked whole-cell current (d, e). I–V relation of the mean patch current evoked by 50 μM carbachol (a) was obtained as a product of NPo and single channel amplitude at each test potential, and is U-shaped at negative potentials with the Erev close to 0 mV (compare to e inset). The 70 pS single channel I–V relation (b) is nearly linear and typical Po-voltage dependence (c) could be fitted by the Boltzmann relation between −120 and −40 mV as shown by the superimposed curve. Note that close to the reversal potential Po values are significantly reduced and therefore these points have been excluded from the fit, similarly to the whole-cell conductance values positive to about −40 mV shown in panel e (see text for details). Panels on the right show examples of single channel activity at different test potentials (from top to bottom: 60 to −120 mV, with an increment of 20 mV excluding 0 and 20 mV where channel activity was undetectable). Whole-cell instantaneous (triangles) and steady-state (circles) I–V relations (d) of current evoked by 50 μM CCh measured from the superimposed traces shown in the inset, were obtained by 1.2 s duration voltage steps applied from a holding potential of −40 mV to test potentials between −120 and 80 mV with increments of 20 mV. The effect of desensitization on the I–V curve was relatively small as during the measurements the holding current was reduced by 11±6% (n=9). Whole-cell I–V relationship (e) obtained by 6 s duration negative-going voltage ramp in the presence of 50 μM carbachol (inset) and the corresponding activation curve obtained by dividing current amplitude by the driving force. Data were fitted between −120 and −40 mV by the Boltzmann relation as shown by the smooth superimposed curve. Note that the activation curve (e) is similar to the Po-voltage dependence of the single channel (c).

Thus, there were three channel types that may contribute to the whole-cell muscarinic current. The activity of the large conductance channel (140 pS) was detected in only a few patches (four out of about 100; exemplified in Figure 1a) and therefore could not be reliably investigated. This channel is probably of negligible physiological importance, due to its low open probability, Po=0.005–0.03 (most openings were very brief, not reaching full amplitude at the frequency setting used), rapid desensitization and low density of this channel expression. However, a possibility still exists that the 140 pS channel can respond to a [Ca2+]i rise and thus be involved in the phenomenon of Ca2+-dependent modulation of the muscarinic current, which is well-established in guinea-pig myocytes and which also exists in the mouse ileum (Dresvyannikov et al., 2005).

In contrast, the activity of the small 17 pS conductance channel was present in three times as many patches (12 out of about 100) but its channel open probability (Po) was also small (0.003–0.08). This, together with its relatively small unitary current amplitude, would result in a negligible contribution to the whole-cell current (estimated at less than 10%) (Figure 1b and c).

The intermediate 70 pS conductance channel was most frequently detected. It had a Po in the range from 0.1 to 0.4 and thus appeared to be the major channel type mediating the whole-cell CCh-evoked cation in mouse ileal myocytes (Figure 1b and c). Apart for some small differences in the single channel conductance and Po values these results were similar to those reported in guinea-pig ileal myocytes (Zholos et al., 2004). Thus, we have focused on the investigation of the properties of the 70 pS channel.

The 70 pS channel could rarely be activated in cell-attached patches with carbachol in the pipette and/or in the bath solutions (compare to Zholos et al., 2004). Thus, for the investigation of its voltage dependency, permeability, gating and pharmacological properties, the outside-out patch-clamp configuration was used and the cation current was activated either by external CCh or by internal GTPγS.

The channel activity showed prominent voltage dependence as both the frequency of channel openings and their durations markedly increased with membrane depolarization. Po of the 70 pS channel was calculated from traces recorded for at least 1 min duration at each test potential (varied from −120 to 60 mV with increments of 20 mV). Po values obtained were plotted against membrane potential (Figure 2c) and fitted with the Boltzmann equation with the potential of half-maximal activation V1/2 of −72.3±9.3 mV and slope factor k of −9.1±7.4 mV (n=3). Average Po value measured at −40 mV was 0.16±0.01 (n=23). Unitary current amplitude was a nearly linear function of the test potential (Figure 2b) whereas the mean patch current that could be measured either as product of NPo and single channel amplitude at each test potential or as the area under the current trace measured after the baseline (closed state) had been adjusted to zero current level (Figure 2a) showed U-shaped voltage dependence similar to that of the steady-state I–V relationship of the CCh-evoked whole-cell current (Figures 2d and e, inset). The instantaneous I–V relationship of the whole-cell current (Figure 2d) was nearly linear similar to the single channel I–V relationship (Figure 2b).

Thus, the whole-cell U-shaped steady-state I–V relationship arises from the voltage dependency of the open probability of the 70 pS channel. Notably, the voltage dependence of the whole-cell cationic conductance could be approximated by the Boltzmann relation (Figure 2e) with V1/2=−65.2±4.3 mV (n=21), which was the same as the single channel Po-voltage dependence (not significant at P=0.56). Close to Erev (about 3 mV for the 70 pS channel) Po was significantly reduced (Figure 2c), which accounted for the region of double rectification of the whole-cell current around its reversal potential (Erev ∼0 mV) (Figure 2a). Thus, it appears that the voltage-dependent properties of the whole-cell CCh-evoked current are mainly determined by the alteration of Po of the 70 pS channel, as it was previously reported for guinea-pig ileal myocytes (Dresviannikov et al., 2004; Dresvyannikov et al., 2004; Zholos et al., 2004).

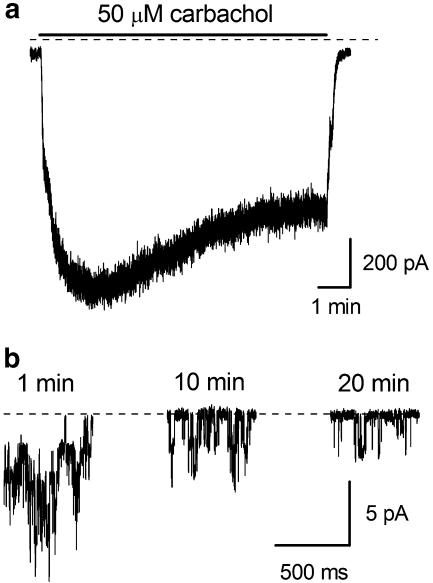

The number of active channels observed in outside-out patches immediately after their formation was usually 2–6 but declined gradually during desensitization. Figure 3a shows whole-cell current decay in a representative cell exposed to 50 μM CCh while Figure 3b illustrates single channel activity recorded at 1, 10 and 20 min after patch formation under identical conditions. 1 mM GTP was added to the pipette solution in both cases since desensitization in guinea-pig ileal myocytes was previously found to be slowed by GTP added to the pipette (Zholos and Bolton, 1996). Two main processes were detected at the single channel level during receptor desensitization. Thus, mean patch current decreased with time both due to a reduced number of active channels and a reduction in Po from NPo(1 min)=0.31 to NPo(20 min)=0.04.

Figure 3.

Time course of whole-cell (a) and single channel (b) desensitization in the presence of 50 μM carbachol at −40 mV. During the first minute after patch excision multiple single channel activity was present in an outside-out patch (b). However, the number of active channels and their Po decreased during 20 min of carbachol application (from 4 to 1 and from 0.31 to 0.04, respectively).

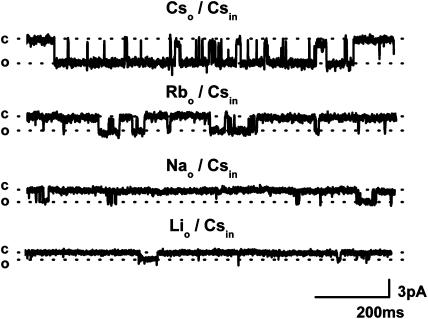

The gating of the 70 pS channel was investigated using different monovalent cations. In these experiments, the external Cs+-containing solution was replaced with Na+, Li+ or Rb+-containing solutions (120 mM) while the same intracellular solution (B, 124 mM Cs+) was used throughout. The single channel unitary conductance with different permeant cations changed in the following order: Cs+ (70 pS)>Rb+ (66 pS)>Na+ (47 pS)>Li+ (30 pS) and representative current traces are shown in Figure 4. The unitary conductance for inward current was calculated at −40 mV (n=3). Notably, the channel openings became less frequent when Cs+ was replaced with Rb+, Na+ or Li+ as Po decreased from 0.24 to 0.06, 0.04 and 0.014, respectively. These results correlate well with the whole-cell data and suggest that the main effect of the permeant cation on the current size is the reduction of Po (17-fold in Na+ solution) rather than unitary conductance (about twofold).

Figure 4.

Dependence of single channel activity on the permeating cation was investigated in the same patch with CsCl-, RbCl-, NaCl- or LiCl-containing external solutions (all at 120 mM; patch pipette contained 124 mM Cs+). Outside-out patch was formed after cation current was fully activated by 200 μM GTPγS.

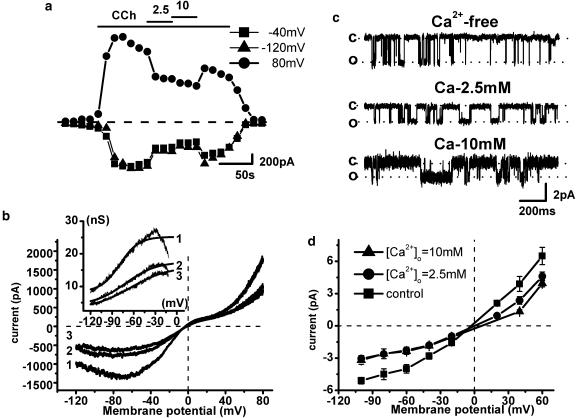

As the muscarinic cation current of the guinea-pig ileum is inhibited by external divalent cations (Zholos and Bolton, 1995) we next addressed the question of Ca2+-dependent modulation of murine MRCC channels. External application of 2.5 and 10 mM Ca2+ in the whole-cell configuration reduced the inward current at −40 mV by 37% and 55%, respectively, and outward current at +80 mV by 49 and 54% (Figure 5a). In the guinea-pig, the inhibitory action of Ca2+ is associated with both reduction of the maximal conductance and positive shift of the activation curve, which also becomes less steep (Zholos and Bolton, 1995). Qualitatively similar biophysical changes of the conductance curve have been observed in mouse myocytes (Figure 5b). Thus, external Ca2+ shifted the activation curve positively from V1/2 −78±2 mV (no added Ca2+) to −67±1 mV (2.5 mM Ca2+) (n=3) and increased the slope factor from −17.9±0.6 to −31±1 mV (Figure 5b). However, the reversal potential of the current was not affected suggesting negligible calcium permeability of cation channels (compare to Zholos and Bolton, 1995). Ca2+ contribution has been previously evaluated at ∼1% under physiological condition (So and Kim, 2003). As shown in Figure 5c, at the single channel level, unitary conductance was reduced from 70 pS with no added Ca2+ to 47±2 and 38±4 pS with 2.5 and 10 mM of external Ca2+, respectively (n=4). In contrast, average Po remained relatively stable and its small reduction could be attributed to the usual desensitization effect described previously. Open channel I–V relationships measured before and after external Ca2+ application are shown in Figure 5d. Similar inhibitory effects of extracellular Mg2+ have also been observed suggesting a nonspecific nature of the external divalent cation effects, likely due to their ‘screening' effect on the negative surface charges in the vicinity of the channel which is expected to reduce external Cs+ concentration locally (Zholos and Bolton, 1995). Rapid channel block as for La3+ (see below) could also contribute to the reduction of the unitary current amplitude. Two and 10 mM of Mg2+ added to the bath solution caused single channel conductance reduction to 60±1 and 32±5 pS (n=3), respectively, and only a small Po decrease (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effects of extracellular Ca2+ on the whole-cell current (a, b) and single channel activity (c, d). Ca2+ added to the bath solution at the indicated concentrations caused rapid whole-cell current decrease at −120, −40 and 80 mV (a). The I–V relations (b) measured with no (trace 1), 2.5 mM (trace 2) and 10 mM added Ca2+ (trace 3) obtained with ramp protocol. Corresponding activation curves fitted by the Boltzmann equation are shown in the inset. Single channel recordings from a representative patch (c) exposed to no, 2.5 and 10 mM added Ca2+. Unitary currents measured at −40 mV were reduced from 2.8±0.26 to 1.85±0.19 and 1.71±0.14 pA, respectively. The open channel I–V relations (d) at different Ca2+ concentrations were obtained from all-point amplitude histograms with no (squares), 2.5 mM (circles) and 10 mM added Ca2+ (triangles).

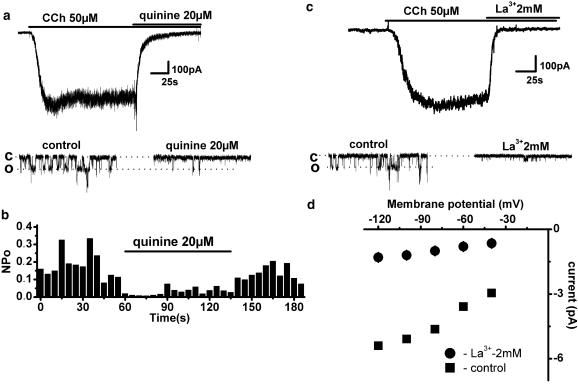

In the next series of experiments, the pharmacological profile of murine ileal MRCC current was investigated. The whole-cell current was rapidly blocked by bath application of either 20 μM quinine or 2 mM La3+ (Figure 6a and c). At the single channel level, the nature of the inhibition was quite different. Quinine caused reversible Po reduction from 0.18 to 0.03 (n=3) without any effect on the single channel unitary conductance (Figure 6b). Such action is consistent with the idea of a blocker that binds to the open channel and dissociates slowly from it and thus is expected to shorten open durations without affecting the unitary current amplitude. In contrast, La3+ appeared to act as a blocker which binds to and dissociates from the open channel rapidly and many times during a single opening as it caused a reduction in single channel conductance to 19±1.7 pS (n=3) accompanied by a moderate Po decrease from 0.16 to 0.07, presumably because rapid blocking and unblocking could not be resolved leading to an apparent reduction in the open channel current (Figure 6c and d). Also, unlike quinine, the effect of La3+ was poorly reversible.

Figure 6.

Inhibitory effects of quinine (a, b) and La3+ (c, d) on carbachol-induced whole-cell and single channel currents measured at −40 mV. Whole-cell (top panel) and single channel (bottom panel) currents were reversibly suppressed by the bath application of 20 μM quinine. Single channel conductance was unaltered while channel NPo decreased from 0.18 to 0.03 (b). Bath application of 2 mM La3+ caused a rapid inhibition of both whole-cell (c top panel) and single channel (c bottom panel) currents. The latter were inhibited mainly via a reduction of the unitary current amplitude (top panel in d, squares and circles show the open channel I–V relationships before and after 2 mM La3+ application, respectively; n=3) as well as variable reduction in NPo (bottom panel in d). No single channel activity was observed at positive potentials in the presence of La3+.

We also considered the possibility that La3+ completely blocked openings of the 70 pS channel, while the remaining activity was due to the 17 pS La3+-insensitive channel gating. However, such significant activity of the 17 pS channel was not seen in control (compare bottom traces in Figure 6c) and therefore such interpretation would require the postulation of a potentiating effect of La3+ on the 17 pS channel together with a complete inhibition of the 70 pS channel. It was also reported earlier that La3+ at low concentration (100 μM) could enhance TRPC5 activity (Jung et al., 2003). However, using 100 μM of La3+ we could not detect any effect on either single channel or whole-cell current (data not illustrated).

SK&F 96365 was previously found to inhibit the muscarinic cation current of the guinea-pig ileum in a voltage-dependent manner (Zholos et al., 2000b). In mouse myocytes, tests showed that 30 μM SK&F 96365 produced both whole-cell and single channel current inhibition with characteristic slow kinetics (data not shown). At the single channel level both Po and channel conductance was reduced while slow changes of Po accounted for the slow time course of the inhibitory effect.

Discussion and conclusions

Muscarinic cationic current has been established as the main mechanism of the cholinergic depolarization in gastrointestinal smooth muscles of various species (for a review see So and Kim, 2003). The channel opening involves simultaneous activation of both M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors with the downstream pathways pinpointed to Gαo and PLC activation (Zholos and Bolton, 1994; Prestwich and Bolton, 1995; Yan et al., 2003). However, despite this important physiological function, the molecular nature of the three types of channels mediating whole-cell current remains unknown. Thus, as one approach to revealing specific roles of each muscarinic receptor subtype as well as the molecular nature of MRCC (presumably belonging to the TRP channel family), gene knockout technology in mouse is now being increasingly used (Gomeza et al., 1999, 2001; Bernardini et al., 2002; Matsui et al., 2002; Stengel and Cohen, 2002; Slutsky et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2005). However, up to now the signal transduction pathways and the single channel basis of the muscarinic current have been best investigated in the guinea-pig ileum. Thus, an important question arose concerning the applicability of the data obtained in the guinea-pig ileum to the mouse model and visa versa.

Our present results suggest that CCh-evoked cation current in smooth muscle cells of murine ileum is generated by three types of MRCC with mean unitary conductances of 17, 70 and 140 pS. A substantial similarity between MRCC subtypes in mouse and guinea-pig ileal myocytes was found. However, at the same time some discrepancies in the large (140 pS) and medium (70 pS) channel activity were observed. Unlike guinea-pig myocytes, the 140 pS was rarely observed in excised patches of murine myocytes, at least at 100 nM [Ca2+]i. However, a possible role of calcium in potentiating this particular channel type activity remains to be explored. The small conductance channel also makes only a trivial contribution to the whole-cell current (estimated at less then 10%). Thus, the whole-cell current appears to be determined predominantly by the 70 pS channel activity.

Medium conductance channel gating was markedly voltage-dependent. In outside-out patches, membrane depolarization increased both frequency and duration of channel openings. Thus, mean patch current generated by the medium conductance channel displayed a distinctive I–V relationship which was prominently U-shaped at negative potentials, which was similar to the whole-cell I–V relation shape. Double rectification around the reversal potential, which is a feature of some TRP currents, occurred mostly due to Po reduction (Figure 2c).

In order to estimate the density of the 70 pS channel, mean values of the whole-cell conductance 14.95±1.02 nS (n=71), single channel unitary conductance 70 pS (n=37) and Po 0.16 (n=23) at the same test potential of −40 mV have been considered. Taking into account the average membrane capacitance of the mouse ileal myocytes of 38.5±2.1 pF (n=40), a channel density of 0.35 μ−2 (on average 1334 channels per cell) was calculated. Despite this higher channel density Po values were considerably lower in mouse compared to guinea-pig ileal myocytes (on average 0.16 vs 0.43; this study and Zholos et al., 2004) as the long channel openings were less frequent in mouse myocytes. This could explain somewhat lower whole-cell muscarinic cation current density in mouse compared to guinea-pig myocytes (15.8±1.8 pA/pF, n=20 vs 19.7±1.3 pA/pF, n=112, respectively). The lower current density can account, at least in part, for the fact that the mouse ileum is less sensitive to the contractile effects of muscarinic agonists compared to the guinea-pig ileum.

Although the density of MRCC in mouse myocytes was about twice as large as in guinea-pig ileal myocytes (Zholos et al., 2004) there was no improvement in the detection of active channels in the cell-attached configuration with CCh in the pipette solution (none in more than 30 attempts). Therefore, a lower channel density does not seem to be a limiting factor for successful cell-attached measurements (Kang et al., 2001). One possible explanation is that M3 receptors may act as a limiting factor since they are less abundant (about 20%) compared to the M2 subtype (about 80%). Recently, interaction of seven transmembrane domains (7-TM) receptors with G-proteins was reported even in the ground state (Kotevic et al., 2005) while at least for K+ channels their colocalization with M2 receptor exists (Dobrzynski et al., 2001), and thus by analogy similar receptor/G protein/channel complexes might occur in the M2 and M3 receptor-MRCC system. However, this issue can be even more complex due to the fact that migration of each component over a short distance may be crucial for channel activation. Such structural arrangements could explain the difficulties of channel activity detection in the cell-attached configuration assuming that the lateral diffusion of membrane proteins is hampered by the pipette and this somehow prevents active complex formation. No water-soluble diffusible factor seems to participate in the channel activation mechanism as the activity of the channel was remarkably persistent in the successful outside-out patches (e.g. Figure 3b).

Nevertheless, some slow desensitization of the whole-cell current was evident and the activation curve of the whole-cell current as a result of desensitization shifted positively (data not shown), presumably due to the positive shift of Po-voltage dependence. At the single channel level, the desensitization process showed up as a decrease of both active channel number and their probability of the open state. Possible mechanisms underlying desensitization process involve activation of the PLC/PKC system and GTP depletion (Zholos and Bolton, 1996; Ahn et al., 1997).

Single channel behaviour strongly depended upon the permeating monovalent cation and external calcium and magnesium concentration. The blocking action of extracellular Ca2+ and Mg2+ was associated mainly with a reduced single channel conductance with only a minor reduction of Po. This suggests that the medium conductance channel type is the main target of divalent cation blocking action. The possible mechanisms of this effect have been previously addressed (Inoue, 1991; Zholos and Bolton, 1995; Kang et al., 2001). The discrepancy in the extent of 2.5 mM [Ca2+]o blocking action which was observed in some of these studies presumably relates to different approaches since in the ‘magnified whole-cell mode', external [Ca2+]o could even activate the channel, probably by local [Ca2+]i increase in the close vicinity of the membrane region (Inoue and Isenberg, 1990b; Kohda et al., 1998). However, 10 mM Ca2+ also strongly increased current noise both in the shut and open states (Figure 5c), probably indicating fast ‘flicker' block, a similar but less pronounced effect compared to La3+. No, or a very small, shift of the reversal potential of the whole-cell and single channel currents at various [Ca2+]o implies that calcium permeability of the channel is negligible.

Consistent with a previous study in guinea-pig gastric myocytes (Kang et al., 2001), we found that different penetrating monovalent cations altered both unitary channel conductance and Po. With Na+ as the main cation, channel activity declined 17-fold compared to Cs+. Thus, at physiological ion concentrations (Na+ 120 mM, Ca2+ 2.5 mM, Mg2+ 1.2 mM) the medium channel had unitary conductance of 25–30 pS and Po ranged from 0.01 to 0.06 (n=3), which is similar to receptor-activated channels in guinea-pig (Dresvyannikov et al., 2004), rabbit portal vein (Inoue and Kuriyama, 1993) and canine pyloric circular muscle (Vogalis and Sanders, 1990).

The effect of well known nonselective cation channel blockers such as quinine, SK&F 96365 and La3+ were also tested in order to compare murine intestinal myocytes with other cell types (Chen et al., 1993; Boulay et al., 1997; Wayman et al., 1997; Lin et al., 1998; Zholos et al., 2000a). We have used nearly saturating blocking concentrations of 20 μM of quinine, 30 μM of SK&F 96365 and 2 mM of La3+. The blockers seemed to act on the cation channel directly since the same blocking effect was observed for the GTPγS-evoked channel current (data not shown). Taken together, our results for the inhibitory effects of quinine, SK&F 96365 and La3+ on the muscarinic cation current in the mouse ileum are consistent with those previously reported for guinea-pig ileal myocytes. However, these findings were extended by describing the inhibitory mechanisms at the single channel level, and these data will undoubtedly allow a useful comparison with the pharmacological properties of the expressed TRPC4 and TRPC5 channel proteins, which have been proposed as the molecular counterparts of the muscarinic cation current (Lee et al., 2003, 2005).

In summary, we have identified three types of muscarinic cation channels in the mouse ileum, of which the 70 pS channel is suggested as the main channel type mediating most of the whole-cell current. This channel appears to be very similar in its voltage-dependent and pharmacological properties to the main muscarinic receptor-activated 60 pS channel expressed in the guinea-pig ileum (Zholos et al., 2004). This study thus opens up an important prospect of rigorous single channel analysis of myocytes from genetically modified mice lacking certain receptors, G proteins or channel proteins which would lead to a more complete understanding of the signal transduction pathways and molecular channel targets involved in the cholinergic excitation of gastrointestinal smooth muscles.

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Supported by The Wellcome Trust grant number 062926.

Abbreviations

- ATP

adenosine 5′ triphosphate magnesium salt

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- GTP

guanosine 5′-triphosphate lithium salt

- GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate)

- HEPES

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid

- I–V relationship

current–voltage relationship

- mICAT

muscarinic receptor cationic current

- MRCC

muscarinic receptor-stimulated cationic channel

- PO

channel open probability

- SK&F 96365

1-[β-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propoxy]-4-methoxyphenethyl]-1H-imidazole·HCl

- 7-TM

seven transmembrane domains

References

- Ahn SC, Kim SJ, So I, Kim KW. Inhibitory effect of phorbol 12,13 dibutyrate on carbachol-activated nonselective cationic current in guinea-pig gastric myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:505–507. doi: 10.1007/s004240050429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini N, Roza C, Sauer SK, Gomeza J, Wess J, Reeh PW. Muscarinic M2 receptors on peripheral nerve endings: a molecular target of antinociception. J Neurosci. 2002;22:RC229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-j0002.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton TB, Zholos AV. Activation of M2 muscarinic receptors in guinea-pig ileum opens cationic channels modulated by M3 muscarinic receptors. Life Sci. 1997;60:1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay G, Zhu X, Peyton M, Jiang M, Hurst R, Stefani E, et al. Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian homolog of Drosophila transient receptor potential (Trp) involved in calcium entry secondary to activation of receptors coupled by the Gq class of G protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29672–29680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, Carter PA, Zhang L, Falcone JF, Stengel PW, Cohen ML, et al. Investigations into the physiological role of muscarinic M2 and M4 muscarinic and M4 receptor subtypes using receptor knockout mice. Life Sci. 2001;68:2473–2479. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Inoue R, Ito Y. Pharmacological characterization of muscarinic receptor-activated cation channels in guinea-pig ileum. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109:793–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynski H, Marples DD, Musa H, Yamanushi TT, Henderson Z, Takagishi Y, et al. Distribution of the muscarinic K+ channel proteins Kir3.1 and Kir3.4 in the ventricle, atrium, and sinoatrial node of heart. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:1221–1234. doi: 10.1177/002215540104901004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresviannikov AV, Zholos AV, Shuba MF. Single nonselective cation channels activated by muscarinic agonists in smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig small intestine. Fiziol Zh. 2004;50:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresvyannikov AV, Bolton TB, Zholos AV. Properties of single muscarinic receptor-gated cation channels in murine intestinal myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;568P:PC14. [Google Scholar]

- Dresvyannikov AV, Zholos AV, Bolton TB, Shuba MF. Carbachol-activated monovalent cation-selective channels in the murine small intestine. Neurophysiol. 2003;35:316. [Google Scholar]

- Dresvyannikov AV, Zholos AV, Shuba MF. Properties of average-conductance cationic channels that mediate cholinergic excitation of guinea-pig ileum myocytes under conditions close to the physiological norm. Neurophysiol. 2004;36:247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Gomeza J, Shannon H, Kostenis E, Felder C, Zhang L, Brodkin J, et al. Pronounced pharmacologic deficits in M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1692–1697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomeza J, Zhang L, Kostenis E, Felder CC, Bymaster FP, Brodkin J, et al. Generation and pharmacological analysis of M2 and M4 muscarinic receptor knockout mice. Life Sci. 2001;68:2457–2466. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R. Effect of external Cd2+ and other divalent cations on carbachol-activated non-selective cation channels in guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 1991;442:447–463. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Isenberg G. Acetylcholine activates nonselective cation channels in guinea pig ileum through a G protein. Am J Physiol. 1990a;258:C1173–C1178. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Isenberg G. Intracellular calcium ions modulate acetylcholine-induced inward current in guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 1990b;424:73–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Kuriyama H. Dual regulation of cation-selective channels by muscarinic and α1-adrenergic receptors in the rabbit portal vein. J Physiol. 1993;465:427–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Muhle A, Schaefer M, Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. Lanthanides potentiate TRPC5 currents by an action at extracellular sites close to the pore mouth. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3562–3571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TM, Kim YC, Sim JH, Rhee JC, Kim SJ, Uhm DY, et al. The properties of carbachol-activated nonselective cation channels at the single channel level in guinea pig gastric myocytes. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;85:291–298. doi: 10.1254/jjp.85.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohda M, Komori S, Unno T, Ohashi H. Carbachol-induced oscillations in membrane potential and [Ca2+]i in guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 1998;511:559–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.559bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostenis E, Conklin BR, Wess J. Molecular basis of receptor/G protein coupling selectivity studied by coexpression of wild type and mutant m2 muscarinic receptors with mutant Gαq subunits. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1487–1495. doi: 10.1021/bi962554d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotevic I, Kirschner KM, Porzig H, Baltensperger K. Constitutive interaction of the P2Y2 receptor with the hematopoietic cell-specific G protein Gα16 and evidence for receptor oligomers. Cell Signal. 2005;17:869–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama H, Kitamura K, Itoh T, Inoue R. Physiological features of visceral smooth muscle cells, with special reference to receptors and ion channels. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:811–920. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KP, Jun JY, Chang IY, Suh SH, So I, Kim KW. TRPC4 is an essential component of the nonselective cation channel activated by muscarinic stimulation in mouse visceral smooth muscle cells. Mol Cells. 2005;20:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YM, Kim BJ, Kim HJ, Yang DK, Zhu MH, Lee KP, et al. TRPC5 as a candidate for the nonselective cation channel activated by muscarinic stimulation in murine stomach. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G604–G616. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00069.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Chen S, Tee D. Effects of quinine on the excitability and voltage-dependent currents of isolated spiral ganglion neurons in culture. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2503–2512. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui M, Motomura D, Fujikawa T, Jiang J, Takahashi S, Manabe T, et al. Mice lacking M2 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are devoid of cholinergic smooth muscle contractions but still viable. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10627–10632. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10627.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestwich SA, Bolton TB. G-protein involvement in muscarinic receptor-stimulation of inositol phosphates in longitudinal smooth muscle from the small intestine of the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutsky I, Wess J, Gomeza J, Dudel J, Parnas I, Parnas H. Use of knockout mice reveals involvement of M2-muscarinic receptors in control of the kinetics of acetylcholine release. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1954–1967. doi: 10.1152/jn.00668.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So I, Chae MR, Kim SJ, Lee SW. Lysophosphatidylcholine, a component of atherogenic lipoproteins, induces the change of calcium mobilization via TRPC ion channels in cultured human corporal smooth muscle cells. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:475–483. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So I, Kim KW. Nonselective cation channels activated by the stimulation of muscarinic receptors in mammalian gastric smooth muscle. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2003;39:231–247. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.39.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel PW, Cohen ML. Muscarinic receptor knockout mice: role of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors M2, M3, and M4 in carbamylcholine-induced gallbladder contractility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;301:643–650. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.2.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel PW, Gomeza J, Wess J, Cohen ML. M2 and M4 receptor knockout mice: muscarinic receptor function in cardiac and smooth muscle in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:877–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogalis F, Sanders KM. Cholinergic stimulation activates a non-selective cation current in canine pyloric circular muscle cells. J Physiol. 1990;429:223–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman CP, McFadzean I, Gibson A, Tucker JF. Cellular mechanisms underlying carbachol-induced oscillations of calcium-dependent membrane current in smooth muscle cells from mouse anococcygeus. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1301–1308. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Miyakawa T, Duttaroy A, Yamanaka A, Moriguchi T, Makita R, et al. Mice lacking the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor are hypophagic and lean. Nature. 2001;410:207–212. doi: 10.1038/35065604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan HD, Okamoto H, Unno T, Tsytsyura YD, Prestwich SA, Komori S, et al. Effects of G-protein-specific antibodies and Gβγ subunits on the muscarinic receptor-operated cation current in guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:605–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Bolton TB. G-protein control of voltage dependence as well as gating of muscarinic metabotropic channels in guinea-pig ileum. J Physiol. 1994;478:195–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Bolton TB. Effects of divalent cations on muscarinic receptor cationic current in smooth muscle from guinea-pig small intestine. J Physiol. 1995;486:67–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Bolton TB. A novel GTP-dependent mechanism of ileal muscarinic metabotropic channel desensitization. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:997–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15770.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Fenech CJ, Prestwich SA, Bolton TB. Membrane currents in cultured human intestinal smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2000a;528:521–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00521.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Tsytsyura YD, Philyppov IB, Shuba MF, Bolton TB. Voltage-dependent inhibition of the muscarinic cationic current in guinea-pig ileal cells by SK&F 96365. Br J Pharmacol. 2000b;129:695–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zholos AV, Zholos AA, Bolton TB. G-protein-gated TRP-like cationic channel activated by muscarinic receptors: effect of potential on single-channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 2004;123:581–598. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200309002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]