Abstract

Background and purpose:

Actions of glutamate and serotonin on their respective receptors in the dorsal facial area (DFA) of the medulla are known to regulate common carotid arterial (CCA) blood flow in cats. Less is known about acetylcholine action on its nicotinic receptor (nAChR) subtypes in the DFA for regulation of CCA blood flow and this aspect was investigated.

Experimental approach:

Nicotinic and muscarinic agonists and antagonists were microinjected into the DFA through a three-barrel tubing in anesthetized cats.

Results:

CCA blood flow was dose-dependently increased by nicotine (a non-selective nAChR agonist) and choline (a selective α7-nAChR agonist). These effects of nicotine were attenuated by α-bungarotoxin (an α7-nAChR antagonist), methyllycaconitine (an α7-nAChR antagonist), mecamylamine (a relatively selective α3β4-nAChR antagonist) and dihydro-β-erythroidine (a relatively selective α4β2-nAChR antagonist). The choline-induced flow increase was attenuated by α-bungarotoxin and mecamylamine, but not by dihydro-β-erythroidine. Muscarinic agonists (muscarine and methacholine) and antagonist (atropine) affected neither the basal nor the nicotine-induced increase in the CCA blood flow.

Conclusions and implications:

Functional α7, α4β2, and α3β4 subunits of the nAChR appear to be present on the DFA neurons. Activations of these receptors increase the CCA blood flow. The present findings do not preclude the presence of other nAChRs subunits. Muscarinic receptors, if any, on the DFA are not involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow. Various subtypes of nAChRs in the DFA may mediate regulation of the CCA and cerebral blood flows.

Keywords: cholinergic receptor, carotid artery, medulla, nAChR, parasympathetic, vascular regulation

Introduction

Kuo et al. (1987) first identified the dorsal facial area (DFA), a reticular area just dorsal to the facial nucleus in the cat. Stimulation of the DFA with glutamate evoked mainly an ipsilateral increase in blood flow of the common carotid artery (CCA) without significant changes in systemic arterial blood pressure (Kuo et al., 1987; Chyi et al., 1995). Glutamate and serotonin, tonically released in the DFA, induce an increase and a decrease, respectively, in the CCA blood flow (Li et al., 1996; Kuo et al., 1999; Gong et al., 2002). The DFA is a parasympathetic nucleus (Kuo et al., 1987, 1992, 1995; Chyi et al., 1995, 2005). It may be functionally and anatomically equivalent to the rat parasympathetic cerebrovasodilator center (Nakai et al., 1993) that is located dorsolaterally to the facial nucleus. Therefore, both areas are likely to be the rostral extension of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV).

Cholinergic nerves are widely distributed in the cortex (Sato et al., 2001; Hotta et al., 2002), hippocampus (Sato and Sato, 1995), striatum (Kaiser and Wonnacott, 2000; Zhou et al., 2002), hypothalamus (Hatton and Yang, 2002) as well as medulla oblongata such as the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) (Kubo et al., 2000, 2002), DMNV and nucleus tractus solitarius (nTS) (Reynolds et al., 1994). Stimulation of nicotinic receptors promotes glutamate release that modulates dopamine releases in a rat striatal slice (Kaiser and Wonnacott, 2000). Cholinergic inputs to the RVLM play a vasopressor effect through muscarinic action (Kubo et al., 2000, 2002). The cholinergic fibers to the rat cortex release acetylcholine to increase the cerebral blood flow via both muscarinic and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the parenchyma of the cortex (Sato et al., 2001). In slice preparations of the rat medulla oblongata, application of acetylcholine to the preganglionic neurons of the DMNV results in marked depolarization through nicotinic action (Ito et al., 1989). Nicotinic receptors in specific medullary regions, such as the nTS (Dhar et al., 2000; Ferguson et al., 2000; Ferreira et al., 2001), the DMNV (Ferreira et al., 2001), the RVLM and caudal ventrolateral medulla (Huangfu et al., 1997; Aberger et al., 2001), play important roles in cardiovascular regulation. The DFA as a parasympathetic nucleus or the rostral extension of the DMNV (Kuo et al., 1987, 1992, 1995; Chyi et al., 1995, 2005), therefore, may quite possibly share some nature of the above-mentioned nuclei that regulate cardiovascular function. Whether nicotinic and/or muscarinic actions and their receptors in the DFA were involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow was not known.

Nicotinic receptors are abundant and play diverse roles in the central nervous system (Decker et al., 1995; Colquhoun and Patrick, 1997). The α7-nAChRs are present in the DMNV (Ferreira et al., 2000, 2001), the chick sympathetic ganglia (Du and Role, 2001) on the striatal glutamatergic terminals (Kaiser and Wonnacott, 2000) and in the hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus (Hatton and Yang, 2002). Both the α7- and α3β4-nAChRs are present in the nTS (Dhar et al., 2000). The α3β4-nAChRs are present in the hippocampus (Alkondon and Albuquerque, 2002; Giocomo and Hasselmo, 2005; Cao et al., 2005). The α4β2-nAChRs are present in the substantia gelatinosa (Kiyosawa et al., 2001). Both the α3β2- and α4β2-nAChRs have been found in the striatum (Kaiser and Wonnacott, 2000). Nevertheless, nAChRs containing α7, α3β4 and α4β2 subunits are most commonly present in the central nervous system. Hence, we focused on these three subunits on the neurons of the DFA, which have not yet been investigated so far as we know.

Our novel findings demonstrate that at least three different subtypes of nAChRs, α7, α3β4 and α4β2 subunits, are present on the DFA neurons, and that their activations increase the CCA blood flow. Muscarinic receptors, if any, on the DFA neurons are not involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow.

Materials and methods

General procedures

The experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Tzu-Chi University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and of the China Medical University Ethical Committee for Animal Research, and were approved by both committees.

Cats (2.0–3.5 kg) of either sex were anesthetized intraperitoneally with α-chloralose (40 mg kg−1) and urethane (400 mg kg−1). End expiratory CO2 concentration was maintained at 3.5–4.5% by artificial ventilation. The rectal temperature was measured and kept at 37.5±0.5°C by an electrical heating pad. Right femoral artery and vein were cannulated with PE-90 polyethylene tubing for measurement of the systemic arterial pressure (SAP) and supplement of fluid, respectively. The ultrasound Doppler probes (diameter 1.5–2.0 mm) were placed around the right and left CCA and monitored with a Directional Pulsed Doppler Flowmeter (University of Iowa, Bioengineering, 545C-4, Iowa, USA). The SAP, heart rate (HR) and CCA blood flows were routinely recorded on a Gould Recorder RS3800 (Cleveland, OH, USA) as described in our previous papers (Li et al., 1996; Gong et al., 2002).

Microinjection technique

The head of cats was immobilized in a David-Kopf stereotaxic instrument. The stereotaxic coordinates of the DFA were about 6 mm rostral to the obex, 3.5 mm lateral to the midline and 3.5 mm ventral to the floor of the fourth cerebral ventricle. The three-barrel electrode tubing was constructed with three stainless-steel tubings (0.3 mm in diameter) glued together and insulated, except the tip at one end. It was inserted into the DFA at an angle of 34° from the vertical axis of the stereotaxic instrument. This facilitated the tubing insertion to be perpendicular to the floor of the fourth cerebral ventricle. Each barrel of this tubing was filled with one of the following chemicals: sodium glutamate, nicotine (a non-selective nAChR agonist), choline (an α7-nAChR agonist), α-bungarotoxin (an α7-nAChR antagonist), methyllycaconitine (an α7-nAChR antagonist), mecamylamine (an α3β4-nAChR antagonist), dihydro-β-erythroidine (an α4β2-nAChR antagonist), muscarine (a muscarinic receptor agonist) and methacholine (a muscarinic receptor agonist). All these drugs were dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing the chemicals (mM) NaCl 119, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 4, CaCl2 4, NaHCO3 26.2, NaH2PO4 1 and glucose 11, and gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at pH 7.4. The aCSF was used as a vehicle control. Each chemical with a volume of 100 nl was microinjected into the DFA in 5 s with the microinjection pump (CMA/100, Carnegie Medicin, North Chelmsford, MA, USA). All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental designs

For localization of the DFA by electrical stimulation of it, cats were further paralyzed with atracurium (GlaxoSmithKline S.p.A., Parma, Italy), initially 0.05 mg kg−1 and 0.02 mg kg−1 intravenously every 20 min, to eliminate interference in recording of blood flow owing to stimulation-induced muscle contraction. The DFA was identified by an increase of the CCA blood flow first induced by the electrical stimulation (20 Hz, 0.5 ms, 100 μA, 10 s) and then by glutamate (50 nmol) stimulation of the DFA through the electrode tubing. The electrode tubing was then maintained there throughout the whole course of the experiment.

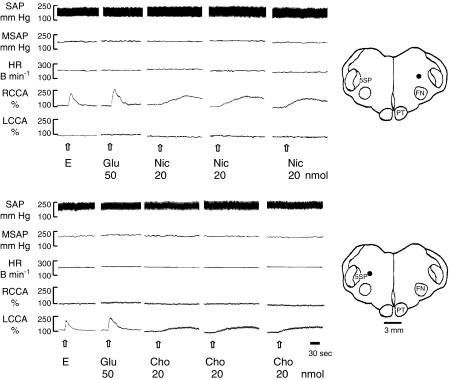

The interval for reproducible increases in the CCA blood flow by repeated microinjections of nicotine (20 nmol) and choline (20 nmol) was 30 min (Figure 1, n=3 for each drug). For the subsequent experiments, each drug was also injected at an interval of 30 min. Dose–responsive effect of nicotine and choline was determined at doses of 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 nmol (n=5 for each drug).

Figure 1.

Typical tracings show the reproducible increase in the CCA blood flow induced by repeating microinjections (20 nl s−1 for 5 s) of nicotine and choline into the DFA at an interval of 30 min. The DFA was first identified by electrical stimulation (E) and then confirmed by glutamate stimulation. Note the ipsilateral increase in the CCA blood flow without changes in HR, SAP and MSAP. The dots on the drawing of medullary sections indicate the injected loci. Abbreviations for this and the following figures: B min−1, beats per min; Cho, choline; DFA, dorsal facial area; E, electrical stimulation (20 Hz, 0.5 ms, 100 μA, 10 s); FN, facial nucleus; Glu, glutamate; HR, heart rate; MSAP, mean systemic arterial pressure; Nic, nicotine; PT, pyramidal tract; RCCA or LCCA, right or left common carotid arterial blood flow; SAP, systemic arterial pressure; 5ST, spinal trigeminal nucleus.

We determined nAChR subunits in the DFA for regulation of the CCA blood flow. Nicotine (40 nmol) and choline (80 nmol) were microinjected into the DFA to increase the CCA blood flow. This effect was then subjected to the effects of nicotinic antagonists, including α-bungarotoxin (2.0, 4.0 and 8.0 pmol), methyllycaconitine (0.025, 0.05 and 0.1 nmol), mecamylamine (1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 nmol) and dihydro-β-erythroidine (0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 nmol) (n=4 for each antagonist). In detail, nicotine (40 nmol) was microinjected to induce an increase in the CCA blood flow. After 30 min, α-bungarotoxin (2 pmol) was injected. After 5 min, the same dose of nicotine was repeated. After 30 min, the same process was repeated for 4.0 and 8.0 pmol α-bungarotoxin. Examination of other nAChR antagonists followed the same procedure as α-bungarotoxin. A similar protocol for choline (80 nmol) was followed.

Whether muscarinic receptors in the DFA might regulate the CCA blood flow was examined in nine animals. Muscarine (10 nmol), methacholine (20 nmol) and atropine (20 nmol) were microinjected into the DFA (n=3 for each drug) to determine if these agonists or antagonist affected the basal CCA blood flow.

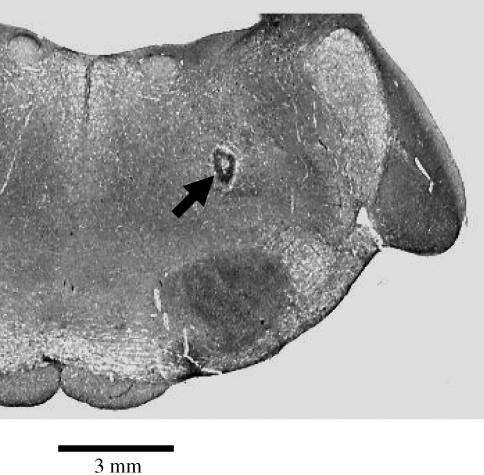

Histology

The stimulated site of the DFA was marked with a pontamine blue (0.1%, 200 nl) microinjection or a lesion produced by DC current of 2 mA for 10 s through the three-barrel electrode tubing. At the end of the experiment, the cat was killed by saturated KCl administered intravenously. The brain was removed and frozen-sectioned at 40 μm thickness on a Cr40 microtome (2800 Frigocut). Proper placement of the probe was confirmed upon microscopic examination. Only cats with correctly positioned electrode tubing in the DFA were considered for data analysis.

Data analysis

Changes in the SAP, HR and CCA blood flow responding to microinjections of chemicals were calculated as (response value−control value)/(control value) × 100%. Data were expressed as means±s.e.m. and analyzed statistically by Student's t-test. The probability level of a significant difference was P<0.05.

Results

Dose-dependent responses of nicotine and choline

The mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP), HR and CCA blood flow in the normal control cats were 140±28 mm Hg, 238±40 beats min−1 and 30±5 ml min−1, respectively (n=52). In control experiments, microinjections into the DFA of any drug vehicle used did not affect MSAP, HR and CCA blood flow.

Repeated microinjections of either 20 nmol nicotine or 20 nmol choline into the DFA at an interval of 30 min (n=3 for each drug) induced reproducible increases in the CCA blood flow in each animal (Figure 1).

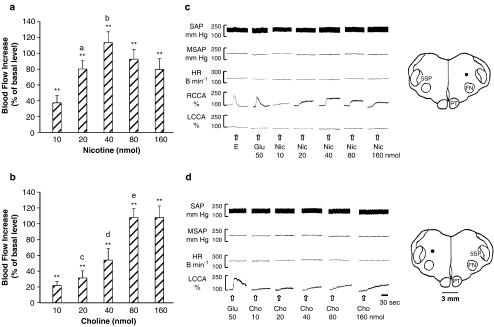

Microinjections of nicotine (Figure 2a and c, n=5) or choline (Figure 2b and d, n=5) into the DFA caused dose-dependent increases of the CCA blood flow, but did not affect the MSAP and HR (Table 1). Nicotine at doses of 10–40 nmol elicited dose-dependent increases in the CCA blood flow, reaching a maximal increase of 114% as compared with the basal level (Figure 2a). The increase was reduced at higher doses of 80 and 160 nmol, probably owing to development of tachyphylaxis to nicotine (Zhang et al., 1998). Microinjections of choline, at doses similar to nicotine, also dose-dependently increased the CCA blood flow (Figure 2b). Choline at 10–80 nmol elicited dose-dependent increases in the CCA blood flow, reaching a maximal increase of 108% as compared with the basal level. The flow increase was not further increased by a greater dose of 160 nmol. Based on these results, 40 nmol of nicotine and 80 nmol of choline were selected for subsequent studies.

Figure 2.

The increase of the CCA blood flow was dose-dependently induced by microinjections into the DFA of nicotine (n=4) (a, c) or choline (n=4) (b, d). (a, b) Statistical analysis; (c, d) original tracings and injection loci (indicated by dots) in the DFA. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. and analyzed by Student's t-test. **P<0.01 vs vehicle; aP<0.01 vs Nic 10 nmol; bP<0.01 vs Nic 20 nmol; cP<0.05 vs Cho 10 nmol; dP<0.05 vs Cho 20 nmol; eP<0.01 vs Cho 40 nmol.

Table 1.

Effect of intra-DFA microinjection of nicotine or choline on changes of MSAP, HR and both sides of CCA blood flow

| nmol | 10 | 20 | 40 | 80 | 160 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine | |||||

| MSAP (%) | 5.3±1.7 | 6.6±0.5 | 7.7±2.0 | 6.4±1.3 | 6.4±1.7 |

| HR (%) | 4.8±4.9 | 5.9±0.8 | 6.8±1.3 | 7.6±1.1 | 6.7±2.1 |

| ICCA (%) | 37±9** | 80±11**, a | 113±14**, b | 93±12** | 80±14** |

| CCCA (%) | 5±2 | 6±1 | 6±2 | 7±3 | 7±3 |

| Choline | |||||

| MSAP (%) | 3.3±0.6 | 5.6±1.6 | 6.5±2.1 | 7.3±1.8 | 6.3±1.8 |

| HR (%) | 4.8±4.9 | 4.2±0.8 | 4.8±2.2 | 6.6±3.2 | 6.5±3.1 |

| ICCA (%) | 22±5** | 31±9**, c | 54±14**, d | 108±11**, e | 108±15** |

| CCCA (%) | 4±1 | 5±2 | 5±3 | 6±2 | 6±3 |

CCA, common carotid arterial blood flow; CCCA, contralateral common carotid artery blood flow; DFA, dorsal facial area; HR, heart rate; ICCA, ipsilateral common carotid artery blood flow; MSAP, mean systemic arterial pressure.

N=5 for either nicotine or choline group. Values are mean±s.e.m.

**P<0.01 vs vehicle;

aP<0.01 vs nicotine 10 nmol;

bP<0.01 vs nicotine 20 nmol;

cP<0.05 vs choline 10 nmol;

dP<0.05 vs choline 20 nmol;

eP<0.01 vs choline 40 nmol by Student's t-test.

Effects of nAChR antagonists on nicotine-induced increase in the CCA blood flow

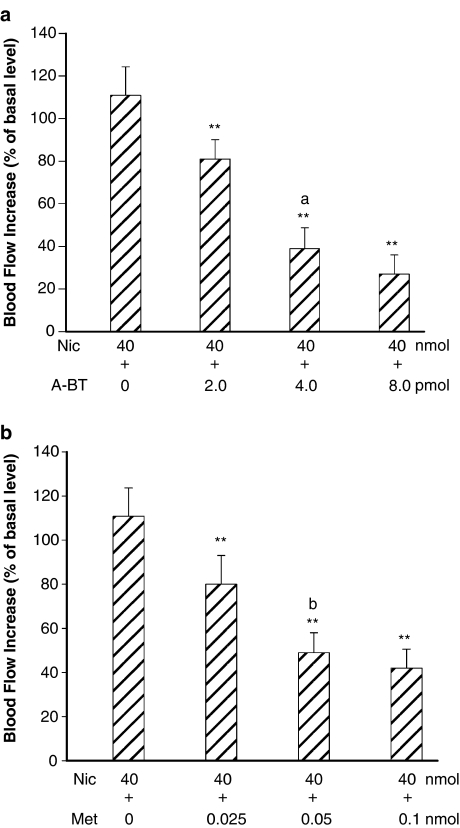

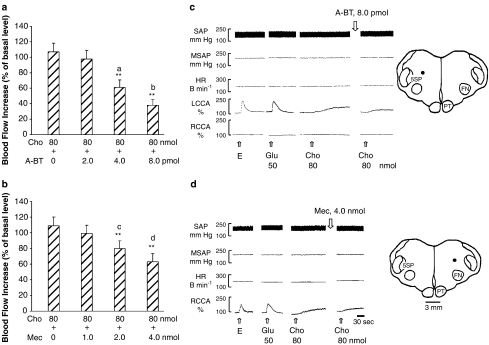

To determine whether nicotinic action was mediated by α7-, α3β4- and α4β2-nAChR subunits in the DFA, selective antagonists were used. The increased CCA blood flow induced by microinjection of 40 nmol nicotine into the DFA was markedly inhibited by pretreatment with 8.0 pmol α-bungarotoxin (A-BT, a selective α7-nAChR antagonist) and 4.0 nmol mecamylamine (Mec, a relative selective α3β4-nAChR antagonist) microinjected into the DFA (Figure 3). The nicotine-induced increases in the CCA blood flow were dose-dependently suppressed by pretreatments of A-BT (Figure 4a, n=4), methyllycaconitine (Met, a selective α7-nAChR antagonist) (Figure 4b, n=4), Mec (Figure 5a, n=4) and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DBE, a relative selective α4β2-nAChR antagonist) (Figure 5b, n=4). In control experiments, all antagonists used did not affect the basal CCA blood flow.

Figure 3.

Typical tracings demonstrate that the increase of CCA blood flow induced by microinjection of nicotine into the DFA was markedly inhibited by pretreatment of α-bungarotoxin (α7 nAChR antagonist) or mecamylamine (α3β4 nAChR antagonist) microinjected into the DFA. Abbreviations: A-BT, α-bungarotoxin; Mec, mecamylamine.

Figure 4.

Interactions of nicotine with selective α7-nAChR antagonists (α-bungarotoxin) (n=4) (a) and methyllycaconitine (n=4) (b), in the DFA. (a) Microinjection of nicotine in the DFA caused an increase of CCA blood flow. The flow increase was dose-dependently reduced by α-bungarotoxin. (b) Microinjection of the same dose of nicotine in other group produced an increase of CCA blood flow. This flow increase was dose-dependently reduced by methyllycaconitine. Abbreviations: Met, methyllycaconitine. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. and analyzed by Student's t-test. **P<0.01 vs Nic 40 nmol; aP<0.01 vs A-BT 2.0 pmol; bP<0.05 vs Met 0.025 nmol.

Figure 5.

Interactions of nicotine with mecamylamine, α3β4 nAChR antagonist (n=4) (a), and dihydro-β-erythroidine, α4β2 nAChR antagonist (n=4) (b), in the DFA. (a) Microinjection of nicotine induced an increase of the CCA blood flow. The flow increase was dose-dependently attenuated by pretreatment with mecamylamine. (b) Microinjection of the same dose of nicotine in another group produced an essentially similar increase of the CCA blood flow. This flow increase was dose-dependently reduced by pretreatment with dihydro-β-erythroidine. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. and are analyzed by Student's t-test. **P<0.01 vs Nic 40 nmol; Abbreviations: DBE, dihydro-β-erythroidine. aP<0.05 vs Mec 1.0 nmol; bP<0.01 vs DBE 0.25 nmol; cP<0.05 vs DBE 0.5 nmol.

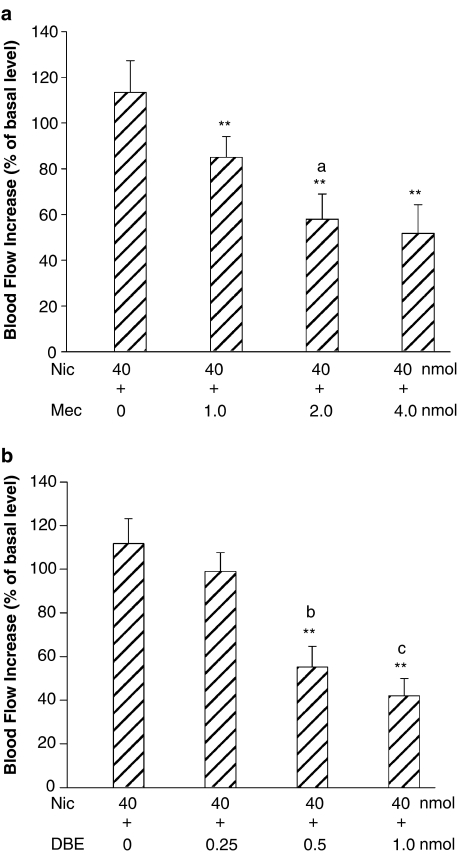

Effects of nAChR antagonists on choline-induced increase in the CCA blood flow

To further test the involvement of α7-, α3β4- and α4β2-nAChRs in nicotinic action in the DFA, choline, a selective α7-nAChR agonist, was used to elicit increases in the CCA blood flow. The increased CCA blood flow was dose-dependently suppressed by prior microinjections in the DFA of A-BT (Figure 6a, n=4) and Mec (Figure 6b, n=4). A-BT and Mec alone did not affect the basal CCA blood flow. DBE affected neither the basal nor the choline-induced increase in the CCA blood flow (n=3, data not shown).

Figure 6.

Interactions of choline with α-bungarotoxin, α7 nAChR antagonist (n=4) (a, c), and mecamylamine, α3β4 nAChR antagonist (n=4) (b, d), in the DFA. (a) Microinjection of choline resulted in an increase of the CCA blood flow. The flow increase was dose-dependently reduced by α-bungarotoxin. (b) Microinjections of the same dose of choline in other group (b) produced an essentially similar increase of the CCA blood flow. This flow increase was reduced by mecamylamine. (a, b) Statistical analysis; (c, d) original experimental tracings and microinjection sites. The dots on the drawing medulla sections indicate the injected loci. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. and analyzed by Student's t-test. **P<0.01 vs Cho 80 nmol; aP<0.01 vs A-BT 2.0 pmol; bP<0.01 vs A-BT 4.0 pmol; cP<0.05 vs Mec 1.0 nmol; dP<0.05 vs Mec 2.0 nmol.

Effects of muscarine and methacholine

Whether muscarinic receptors were involved in the DFA was assessed by microinjections in the DFA of muscarinic agonists, muscarine (5 nmol in one animal and 10 nmol in two animals) and methacholine (10 nmol in one animal and 20 nmol in two animals) as well as muscarinic antagonist, atropine sulfate (10 nmol in one animal and 20 nmol in two animals). Neither agonists nor antagonist affected the basal CCA blood flow or the MSAP.

Verification of injection site

Figure 7 shows a photograph of the coronal section of the medulla indicating the injected site in the DFA. This site is located 6 mm rostral to the obex, 3.5 mm lateral to the midline and 3.5 mm ventral to the floor of the fourth cerebral ventricle.

Figure 7.

A photograph of a coronal medulla section, 6 mm rostral to the obex, 3.5 mm lateral to the midline and 3.5 mm ventral to the dorsal surface of the medulla, indicates microinjection site (indicated by an arrow) in the DFA.

Discussion

In the present experiment, we assessed the effects of various nicotinic and muscarinic agonists and antagonists on the DFA in regulation of the CCA blood flow. The results suggest for the first time that three functional subunits of nAChRs, namely, α7, α4β2 and α3β4 subunits, on the neurons in the DFA participate in regulation of the CCA blood flow. On the other hand, muscarinic receptors, if any, on the DFA neurons do not appear to be involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow.

The presence of nAChRs on the DFA neurons (or synaptic terminals) was suggested from the present finding that microinjections into the DFA of various doses of nicotine, a non-selective nAChR agonist that stimulates various subunits of nAChRs (Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997; Si and Lee, 2002; Amtage et al., 2004), resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the CCA blood flow (Figure 2a and d). This increase was dose-dependently inhibited by different nicotinic receptor antagonists, A-BT, Met, Mec and DBE (Figures 4 and 5).

The presence of α7-nAChR on the DFA neuron was suggested based on the following findings. First, choline, a precursor of acetylcholine and a metabolic product of acetylcholine, acts as a relatively selective agonist for α7-containing nAChR (Alkondon et al., 1997; Si and Lee, 2002). Microinjections of various doses of choline in the DFA resulted in a dose-dependent increase of CCA blood flow (Figure 2b and c). Second, A-BT (CaChelin and Rust, 1995; Lopez et al., 1998; Ferreira et al., 2000, 2001; Si and Lee, 2002) and Met (Alkondon et al., 1997; Si and Lee, 2002), selective antagonists for nAChRs containing α7 subunit, dose-dependently suppressed the increase in the CCA blood flow induced by nicotine (Figure 4) and choline (Figure 6a and c).

The presence of α3β4- and α4β2-nAChRs on the neurons of the DFA was evident from our findings that pretreatments in the DFA of various doses of either Mec (Figure 5a) or DBE (Figure 5b) attenuated the nicotine-induced increase in the CCA blood flow in a dose-dependent manner. Mec and DBE are partial antagonists for nAChRs containing α3β4 and α4β2 subunits, respectively (Alkondon et al., 1997; Webster et al., 1999). They, however, have been considered as unselective nAChR antagonists that may act at nAChRs subunits other than α3β4 and α4β2 in human (Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997; Amtage et al., 2004; Si and Lee, 2002). Therefore, the present findings do not preclude the presence of nAChRs subunits other than α3β4 and α4β2.

Choline, a selective α7 nAChR agonist (Alkondon et al., 1997; Si and Lee, 2002), appears to act as a partial agonist at α3β4-nAChRs on PC12 cells (Alkondon et al., 1997). In concert with the finding, the present experiment demonstrated that Mec, a partial α3β4-nAChR antagonist (Alkondon et al., 1997; Webster et al., 1999), attenuated the choline-induced increase in the CCA blood flow (Figure 6b), indicating that Mec also partially blocked α7-nAChR. The order of preferential targets for Mec in human appears to be α4β4∼α2β4>α2β2∼α4β2∼α7 (Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997; Amtage et al., 2004). Choline, however, did not act as an agonist on α4β2-nAChR, as DBE did not affect the choline-induced increase in the CCA blood flow (data not shown), supporting the finding that choline did not activate α4β2-nAChRs on hippocampal neurons (Alkondon et al., 1997).

The DFA gives rise to axons that contribute to the parasympathetic preganglionic fibers of the seventh and ninth cranial nerves (Chyi et al., 1995, 2005). Through these nerves, glutamate stimulation of the DFA increases the CCA blood flow (Kuo et al., 1987, 1992, 1995; Chyi et al., 1995, 2005) via AMPA and NMDA receptors on the neurons in the DFA (Gong et al., 2002). The release of serotonin (5-HT) in the DFA, acting through 5-HT2 receptor, suppresses the release of glutamate in the DFA (Li et al., 1996). The present experiment for the first time demonstrated that activation of α7-, α4β2- and α3β4-nAChRs in the DFA increased the CCA blood flow. It is not yet known whether these nAChRs are modulated by glutamatergic and serotonergic receptors in the DFA. Nevertheless, nicotinic activation to the DFA may likely mediate through the seventh and ninth parasympathetic nerves to increase the CCA blood flow as glutamatergic and serotonergic activations.

Electrical or glutamate stimulation of the DFA induces not only the increase in the CCA blood flow but also the increase in the cerebral blood flow (Kuo et al., 1995). Glutamate stimulation of the parasympathetic cerebrovasodilator center in rats (Nakai et al., 1993), an area likely equivalent to the DFA in cats (Kuo et al., 1987, 1992, 1995, 1999; Chyi et al., 1995, 2005; Li et al., 1996; Gong et al., 2002), increases cortical blood flow. Whether the cerebral or cortical blood flow is also regulated by nicotinic action in the DFA deserves further investigation.

Muscarinic receptors may not be present on the DFA neurons to regulate CCA blood flow. This was evident from the present finding that microinjections of muscarinic receptor agonists (muscarine and methacholine) and antagonist (atropine) did not affect the basal or the nicotine-increased CCA blood flow. Muscarinic receptors, if any, on the DFA neurons are not likely involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow.

In summary, we demonstrate for the first time that the neurons in the DFA contain at least three functional subunits of nAChRs, namely, α7, α4β2 and α3β4-nAChRs. Activation of these receptors results in increased CCA blood flow. Nevertheless, the present findings do not preclude the presence of nAChRs subunits other than α7, α3β4 and α4β2. On the other hand, muscarinic receptors, if any, in the DFA are not likely involved in regulation of the CCA blood flow. Based on our previous (Li et al., 1996; Kuo et al., 1999; Gong et al., 2002) and the present findings, glutamate, serotonin and nAChRs are present in the DFA and may play roles in regulation of the CCA and possibly the cerebral blood flows (Kuo et al., 1995).

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC92-2320-B-320-017 to JSK and NSC92WFD2700042 to TJFL) and Taichung Veterans General Hospital (TCVGH-927318D to JSK), Taiwan.

Abbreviations

- A-BT

α-bungarotoxin

- CCA

common carotid artery

- CVLM

caudal ventrolateral medulla

- DBE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- DFA

dorsal facial area

- DMNV

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- Glu

glutamate

- HR

heart rate

- Mec

mecamylamine

- Met

methyllycaconitine

- MSAP

mean systemic arterial pressure

- nAChRs

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- nTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- RVLM

rostral ventrolateral medulla

- SAP

systemic arterial pressure

References

- Aberger K, Chitravanshi VC, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular responses to microinjection into the caudal ventrolateral medulla of the rat. Brain Res. 2001;892:138–146. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. A non-alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulates excitatory input to hippocampal CA1 interneurons. J Neurosci. 2002;87:1651–1654. doi: 10.1152/jn.00708.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Barbosa CT, Albuquerque EX. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activation modulates gamma-aminobutyric acid release from CA1 neurons of rat hippocampal slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1396–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amtage F, Neughebauer B, McIntosh JM, Freiman T, Zentner J, Feuerstein TJ, et al. Characterization of nicotine receptors inducing noradrenaline release and absence of nicotinic autoreceptors in human neocortex. Brain Res Bull. 2004;62:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin AB, Rust G. Beta subunits co-determine the sensitivity of rat neuronal nicotine receptors to antagonists. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1995;429:449–451. doi: 10.1007/BF00374164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao YJ, Suroway CS, Puttfarcken PS. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated [3H] dopamine release from hippocampus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1298–1304. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.076794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Crona JH, Washburn MS, Urrutia A, Elliott KJ, Johnson EC. Pharmacological characterization of recombinant human neural nicotinic acetylcholine receptors h alpha 2 beta 2, h alpha 2 beta 4, h alpha 3 beta 2, h alpha 3 beta 4, h alpha 4 beta 2, h alpha 4 beta 4, h alpha 7 expressed in xenopus oocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyi T, Cheng V, Chai CY, Kuo JS. Vasodilatation produced by stimulation of pavocellular reticular formation in the medulla of anaesthetised-decerebrated cats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;56:69–74. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyi T, Wang SD, Gong CL, Lin SZ, Cheng V, Kuo JS. Preganglionic neurons of the sphenopalatine ganglia reside in the dorsal facial area of the medulla in cats. Chin J Physiol. 2005;48:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun LM, Patrick JW. Pharmacology of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;39:191–220. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker MV, Brioni JD, Bannon AW, Arneric SP. Diversity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: lessons from behavior and implications for CNS therapeutics. Life Sci. 1995;56:545–570. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00488-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S, Nagy F, McIntosh JM, Sapru HN. Receptor subtypes mediating depressor responses to microinjections of nicotine into the medial nTS of the rat. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:R132–R140. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du C, Role LW. Differential modulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and synaptic transmission in chick sympathetic ganglia by PGE (2) J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2498–2508. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DG, Haxhiu MA, To AJ, Erokwu B, Dreshaj IA. The alpha3 subtype of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor is expressed in airway-related neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius, but is not essential for reflex bronchoconstriction in ferrets. Neurosci Lett. 2000;287:141–145. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M, Ebert SN, Perry DC, Yasuda RP, Baker CM. Evidence of a functional alpha7-neuronal nicotinic receptor subtype located on motor neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:260–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M, Singh A, Dretchen KL, Kellar KJ, Gill RA. Brainstem nicotinic receptor subtypes that influence intragastric and arterial blood pressures. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:230–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giocomo LM, Hasselmo ME. Nicotinic modulation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in region CA3 of the hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1349–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong CL, Lin NN, Kuo JS. Glutamatergic and serotonergic mechanisms in the dorsal facial area for common carotid artery blood flow control in the cat. Auton Neurosci. 2002;101:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton GI, Yang QZ. Synaptic potentials mediated by alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in supraoptic nucleus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:29–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00029.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta H, Uchida S, Kagitani F. Effects of stimulating the nucleus basalis of Meynert on blood flow and delayed neuronal death following transient ischemia in the rat cerebral cortex. Jpn J Physiol. 2002;52:383–393. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.52.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Schreihofer M, Guyenet PG. Effect of cholinergic agonists on bulbospinal C1 neurons in rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R249–R258. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.1.R249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito C, Fukuda A, Nabekura J, Oomura Y. Acetylcholine causes nicotinic depolarization in rat dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, in vivo. Brain Res. 1989;503:44–48. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser S, Wonnacott S. Alpha-bungarotoxin-sensitive nicotinic receptors indirectly modulate [(3)H]dopamine release in rat striatal slices via glutamate release. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:312–318. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosawa A, Katsurabayashi S, Akaike N, Pang ZP, Akaike N. Nicotine facilitates glycine release in the rat spinal dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2001;536:101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T, Hagiwara Y, Endo S, Fukumori R. Activation of hypothalamic angiotensin receptors produces pressor responses via cholinergic inputs to the rostral ventrolateral medulla in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Brain Res. 2002;953:232–245. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo T, Hagiwara Y, Sekiya D, Chiba S, Fukumori R. Cholinergic inputs to rostral ventrolateral medulla pressor neurons from hypothalamus. Brain Res Bull. 2000;53:275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JS, Chyi T, Cheng V, Wang JY. Immunocytochemical characteristics of dorsal facial area of the medulla in cats. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1992;22:1186. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JS, Chyi T, Yang MCM, Chai CY. Changes in intra- and extra cranial tissue blood flow upon stimulation of a reticular area dorsal to the facial nucleus in cats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:87–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb01961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JS, Li HT, Lin NN, Yang CS, Cheng FC. Dorsal facial area of cat medulla: 5-HT2 action on glutamate release in regulating common carotid blood flow. Neurosci Lett. 1999;266:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo JS, Wang MR, Liu RH, Yu CY, Chiang BN, Chai CY. Reduction of common carotid resistance upon stimulation of an area dorsal to the facial nucleus of cats. Brain Res. 1987;417:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Chen WY, Liu L, Yang CS, Cheng FC, Chai CY, et al. The dorsal facial area of the medulla in cats: inhibitory action of serotonin on glutamate release in regulating common carotid blood flow. Neurosci Lett. 1996;210:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MG, Montiel C, Herrero CJ, Garcia-Palomero E, Mayorgas I, Hernandez-Guijo JM, et al. Unmasking the functions of the chromaffin cell alpha7 nicotinic receptor by using short pulses of acetylcholine and selective blockers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14184–14189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai M, Tamaki K, Ogata J, Matsui Y, Maeda M. Parasympathetic cerebrovasodilator center of the facial nerve. Circ Res. 1993;72:470–475. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds DJ, Lowenstein PR, Moorman JM, Grahame-Smith DG, Leslie RA. Evidence for cholinergic vagal afferents and vagal presynaptic M1 receptors in the ferret. Neurochem Int. 1994;25:455–464. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(94)90022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Sato Y. Cholinergic neural regulation of regional cerebral blood flow. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato A, Sato Y, Uchida S. Regulation of regional cerebral blood flow by cholinergic fibers originating in the basal forebrain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2001;19:327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(01)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si ML, Lee TJF. Alpha7-nAChRs on cerebral perivascular sympathetic nerves mediate choline-induced nitrergic neurogenic vasodilation. Circ Res. 2002;91:62–69. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000024417.79275.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JC, Francis MM, Porter JK, Robinson G, Stokes C, Horenstein B, et al. Antagonist activities of mecamylamine and nicotine show reciprocal dependence on beta subunit sequence in the second transmembrane domain. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1337–1348. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Edvinsson L, Lee TJF. Mechanism of nicotine-induced relaxation in the porcine basilar artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:790–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou FM, Wilson CJ, Dani JA. Cholinergic interneuron characteristics and nicotinic properties in the striatum. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:590–605. doi: 10.1002/neu.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]