Abstract

Background and purpose:

Diabetes mellitus, especially type 2, is associated with increased arterial thrombosis. Our aims were (i) to characterize and compare platelet aggregation in vivo and in vitro in a type 2 diabetes model; and (ii) to determine whether these results differ from those in a type 1 diabetes model.

Experimental approach:

Platelet aggregation to ADP in lean or obese Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats and in streptozotocin (STZ)-treated or control Wistar rats was measured in vitro, using Born aggregometry, and in vivo, by 111Indium-labelled pulmonary platelet accumulation.

Key results:

In vivo, ADP responses were higher in obese (type 2 model) than lean ZDF rats. However, in vitro, ADP aggregation did not differ between platelet-rich plasma from ZDF lean or obese rats; nor was any difference seen in ADP responses when platelets from either lean or obese ZDF rats were suspended in plasma from obese or lean ZDF rats, respectively. In vivo, ADP responses were similar in STZ treated (type 1 model) and control rats whereas, in vitro, isolated platelets from STZ diabetic rats were more responsive to ADP aggregation than controls. Platelets from control or STZ-treated rats suspended in plasma from STZ-treated rats exhibited reduced ADP aggregation, compared to when suspended in plasma from control rats.

Conclusions and implications:

The platelet aggregation results obtained in vitro do not reflect those in vivo, therefore in vitro aggregation data should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, both in vitro and in vivo, different diabetic models exhibit important differences in platelet responsiveness.

Keywords: ZDF rat, type II diabetes, platelets, ADP, platelet aggregation

Introduction

The major physiological function of platelets is to mediate the haemostatic response (Hourani and Cusack, 1991). When a blood vessel is damaged, platelets adhere to the exposed subendothelium, where they become activated and aggregate to form a haemostatic plug, in order to arrest the flow of blood and seal off the damaged vessel wall. Platelet activation is controlled by several substances endogenous to the vasculature, such as thrombin, collagen, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine. These agonists act through specific receptors expressed on the platelet surface membrane and initiate signal transduction pathways that lead to platelet activation. However, in pathological conditions, platelets form thrombi at the site of vascular lesions and these are associated with ischaemic events and progression of atherosclerosis. Furthermore, there is evidence of platelet hypersensitivity to aggregating agents in patients with risk factors for coronary heart disease such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes mellitus (Willoughby et al., 2002).

Most of the morbidity and mortality seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, especially in type II (‘non-insulin dependent') diabetes, is the result of micro- and macrovascular occlusive disease in which thrombosis plays an important part (Nathan, 1993; Sobol and Watala, 2000). As platelets play a pivotal role in thrombus formation, an increase in platelet reactivity is one potential mechanism that could explain the increased incidence of thrombotic disease seen in the diabetic population (Winocour, 1992; Colwell and Nesto, 2003). Although, overall, results are conflicting, support for this suggestion has come from studies which have demonstrated increased in vitro aggregation responses of washed platelets from both diabetic patients (Vericel et al., 2004) and experimental animals rendered hyperglycaemic (Eldor et al., 1978). However, some studies of platelet aggregation in plasma or whole blood have suggested that platelets in diabetes are in fact similarly reactive to control platelets (Judge et al., 1995). Although the reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, part of the explanation may relate to the presence, in some models, of as yet uncharacterized platelet inhibitory factors (or by the lack of stimulating factors) in diabetic plasma (Eldor et al., 1978; Takahashi et al., 1986; Takiguchi et al., 1992).

Increased platelet reactivity could also be due to reduced production of factors that inhibit platelet activation, in particular, nitric oxide (NO). NO is produced by both the vascular endothelium and by platelets themselves, and inhibits platelet aggregation and adhesion. Endothelial-derived NO has been shown to be reduced in diabetes (Sobrevia and Mann, 1997), as has platelet-derived NO (Queen et al., 2003). Although the importance of platelet-derived NO is still unclear, there is evidence to suggest that it acts as a negative feedback system to regulate platelet aggregation (Radomski et al., 1990), as well as being important in the regulation of platelet recruitment (Freedman et al., 1997). Defects in the normal modulator role of the endothelium on platelet function in vivo may also be crucial in the development of vascular thrombotic complications in diabetes (Cohen, 1993; De Vriese et al., 2000).

Although several groups have reported in vitro platelet aggregometry data in both animal and human diabetes, very few data exist on platelet responses in vivo in diabetes. We and others have characterized extensively a radio-isotopic method for studying platelet responses in vivo in experimental animals (Page et al., 1982; Oyekan and Botting, 1986; May et al., 1990; Itoh et al., 1996). In the present work, we have employed the widely used Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rat model of type II diabetes to characterize type II diabetes-induced alterations in (i) intrinsic platelet responsiveness, as determined with platelets in vitro, and (ii) platelet responsiveness in vivo, assessed as pulmonary platelet accumulation in the whole animal. We have also measured the same parameters in control and streptozotocin (STZ)-treated rats (a model of type 1 diabetes) to determine whether in vitro and in vivo platelet responsiveness may differ between models of diabetes.

Methods

Animals

Male ZDF obese (fa/fa) and lean (fa/+) rats (Charles River, Margate, UK) were obtained at 6 weeks of age. They received Purina 5008 chow and water ad libitum. Adult male Wistar rats (Harlan UK Ltd, Bicester, UK), aged 7 weeks at time of receipt, received a standard chow diet and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with Home Office Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. ZDF rats were maintained on Purina 5008 chow until 11–12 weeks of age, at which time point they were studied. Wistar rats were rendered hyperglycaemic by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of STZ 50 mg kg−1 in 0.9% sterile saline. Control animals were treated with an equal volume of saline (0.1 ml 100 g−1, i.p.); 48–72 h post-injection, urine glucose levels were measured using Diastix urine reagent strips to confirm diabetogenesis. Animals were studied 3 weeks following STZ treatment.

On the day of experiment, all animals were anaesthetized with urethane (1.5 g kg−1, i.p.), a small blood sample (100 μl) was obtained from a tail vein and blood glucose was measured in this sample using an Advantage II Accu-Check monitor.

Preparation of platelets

Blood, 4.5 ml, was collected from the abdominal aorta of urethane-anaesthetized animals into 0.5 ml trisodium citrate (3.8% w/v) and centrifuged (250 g, 15 min, room temperature) to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP).

For in vitro platelet aggregation studies, PRP was centrifuged (650 g, 15 min, room temperature) and, after removal of the supernatant plasma, the surface of the platelet pellet was rinsed three times with Ca2+-free Tyrode solution (composition in mM: NaCl 137; KCl 2.7; MgSO4 1.0; NaHCO3 11.9; NaH2PO4 0.42; glucose 0.56; HEPES 5.0; pH 7.4) and the pellet subsequently resuspended in the same buffer.

For in vitro studies of the effect of plasma on platelet aggregation, PRP pooled from 3 to 4 animals was split into two aliquots and centrifuged (650 g, 15 min, room temperature) to pellet the platelets. Platelets from lean or obese ZDF rats were then resuspended in platelet-poor plasma (PPP) from either group. Similarly, platelets from control and STZ-treated animals were resuspended in PPP from either group.

For in vivo platelet accumulation studies, platelets were radiolabelled with 111Indium (111In) essentially as described previously (Page et al., 1982; May et al., 1990). Briefly, PRP was buffered in Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing prostaglandin E1 (PGE1; 300 ng ml−1) and centrifuged at 650 g (15 min, room temperature). After removal of the supernatant, the surface of the platelet pellet was carefully rinsed with the same buffer solution. The platelets were gently suspended in 1 ml buffer and incubated for 5 min at room temperature with 1.5 MBq 111In oxine. After a further centrifugation (650 g, 15 min, room temperature), the supernatant containing free 111In oxine was removed and the platelets resuspended in 1 ml buffer. In order to ensure that the changes in radioactivity seen were due to platelet accumulation and not simply a consequence of changes in blood distribution, in some experiments erythrocytes were harvested instead of platelets, labelled with 111In and used in experiments following the same protocol described above.

In vitro measurement of platelet aggregation

Aggregation responses of isolated platelets in Tyrode buffer or platelets suspended in plasma were measured turbidimetrically using a Payton dual-channel 600B model aggregometer. Samples, 300 μl, at 37°C were stirred at 600 r.p.m. with a magnetic stirrer. The aggregometer was calibrated using the light transmission of PRP/platelet suspension and PPP/Tyrode buffer to represent 0 and 100% aggregation, respectively. Following the addition of Ca2+ (final concentration 1 mM), in order to re-establish physiological ambient Ca2+ concentration, aggregation was stimulated with ADP (concentration range 0.3–30 μM) and recorded for 2 min or until a plateau was reached. Preliminary experiments, using serial dilutions of PRP (up to 1:5), established that % aggregation responses to ADP were not affected by platelet count in the PRP (data not shown).

In vivo measurement of labelled cell accumulation

In vivo cell accumulation responses were measured essentially as described previously (May et al., 1990). 111In-labelled platelets (or, in some experiments, 111In-labelled erythrocytes) were administered to urethane-anaesthetized rats via a butterfly cannula placed in a tail vein, and allowed to equilibrate in the circulation for 40 min before challenge with platelet agonists. This also allowed time for the small amount of PGE1 injected with the labelled cells to be inactivated, as the pharmacological half-life of PGE1 in the rat has been shown to be approximately 9 min (Perper et al., 1975). Furthermore, this allowed the radiolabelled platelets to re-equilibrate in a normal calcium environment. Circulating 111In-labelled cells were continuously monitored in the pulmonary circulation by means of 2.5 cm crystal scintillation probes placed over the thorax. Counts were detected with a multi-channel gamma spectrometer (Nuclear Enterprises Ltd, Edinburgh, UK) and logged, via a special application interface (AIMS 8000, Mumed, London, UK), by a microcomputer.

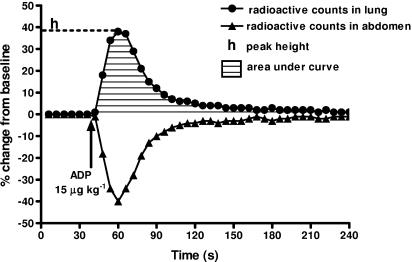

Following administration of intravenous bolus doses of ADP (dose range 1–30 μg kg−1), radioactivity in the pulmonary vasculature was continuously monitored, and changes from stable baseline values before injection were stored and expressed as percentage change. Responses are expressed as (a) peak response (maximum % change); and (b) area under the curve (AUC; overall response, measured over 90 s) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A typical experimental trace showing the effect of ADP (15 μg kg−1) on platelet accumulation in vivo. The results are expressed as changes in radioactive counts in the lung and abdomen as a function of time. The diagram also shows the two parameters – peak height and AUC (over 90 s) – that were used to assess responses.

Biochemical analyses

Plasmal cholesterol and triglycerides

Total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured on a Vitros 950 analyser (Ortho Diagnostics, Amersham, UK).

Plasma von Willebrand factor

von Willebrand factor (vWF) antigen levels in plasma samples were measured using a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Helena Labs, Beaumont, Texas, USA) on 96-well plates. Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used as chromogen and optical densities were read at 450 nm. Values were interpolated from a standard curve and expressed as % of a standard plasma sample.

Plasma nitrate+nitrite

Nitrate+nitrite (NOx) levels in plasma samples were measured using a commercial Griess colorimetric assay (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA) on a 96-well plate. Optical densities were read at 540 nM and values interpolated from a standard curve. Values are expressed as μM.

Plasma insulin

Insulin levels in plasma samples were measured using a commercial rat/mouse insulin solid phase, two-site ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) in 96-well plates. TMB was used as chromogen and optical densities were read at 450 nm. Values were interpolated from a standard curve and are expressed as ng ml−1.

Plasma advanced glycation end products

Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in plasma samples were measured by competitive, carboxymethyllysine (CML)-specific ELISA in 96-well plates. o-Phenylene diamine was used as the colorimetric substrate and optical densities were read at 490 nm. Values are expressed as μg ml−1 CML.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. values throughout. Statistical analyses were by analysis of variance with or without repeated measures as appropriate, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Materials

ADP, insulin, PGE1, STZ and urethane were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (Dorset, UK). 111In oxine was from Amersham plc (Little Chalfont, UK). Sterile saline was purchased from Baxter Healthcare (Thetford, UK). Diastix Urine Reagent strips were from Bayer (Newbury, UK) and the Advantage II Accu-Check Monitor and blood glucose sticks were from Roche (Lewes, UK). Insulin ELISA kit was obtained from Mercodia AB, Sweden.

Results

Characteristics of ZDF rats

The morphological and biochemical characteristics of lean and obese ZDF rats (at 11–12 weeks of age) are shown in Table 1. Obese ZDF rats were heavier than lean animals and had higher blood glucose levels. Obese ZDF rats had higher plasma levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, insulin, NOx and vWF than their lean counterparts. There was no difference in CML levels between the two groups.

Table 1.

Morphological and biochemical characteristics of ZDF rats

| Lean | Obese | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 302±5 | 351±4* |

| Glucose (mM) | 7.6±0.4 | 26.0±0.8** |

| Total cholesterol (mmol l−1) | 1.55±0.03 | 2.80±0.22* |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 0.72±0.04 | 4.76±0.56** |

| vWF (% of reference) | 20.3±0.6 | 27.7±0.2* |

| NOx (μM) | 3.5±0.4 | 9.2±1.4* |

| Insulin (ng ml−1) | 1.11±0.28 | 2.96±0.59* |

| CML (μg ml−1) | 0.92±0.05 | 1.09±0.11 |

Abbreviations: CML, carboxymethyllysine; vWF, von Willebrand factor; ZDF, Zucker Diabetic Fatty.

Measurements were carried out on blood or plasma samples from 11- to 12-week-old animals.

P<0.05

P<0.01; n=18/group (weight and blood glucose) or n=4/group (all other measures).

In vivo platelet aggregation (ZDF rats)

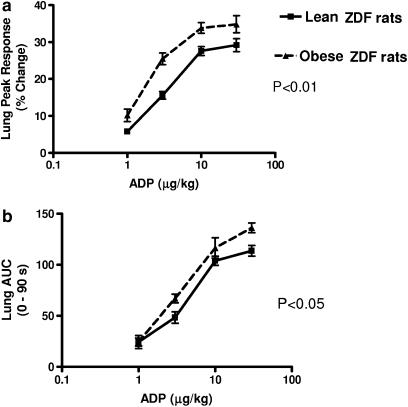

In vivo, in anaesthetized ZDF rats, ADP dose-dependently induced reversible accumulation of radiolabelled platelets in the pulmonary vasculature, assessed as an increase in radioactive counts in the thoracic region. In all experiments, increases in measured radioactivity over the thorax were mirrored exactly by corresponding decreases in the abdominal counts (as exemplified by the trace shown in Figure 1); therefore, for clarity, only results for pulmonary platelet accumulation are reported here. Pulmonary platelet accumulation in response to ADP in vivo was greater in obese ZDF than in lean ZDF rats, both as determined by maximal responses and by AUC (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ADP-induced platelet aggregation responses in vivo in ZDF rats. Pulmonary platelet accumulation responses expressed as peak height (a) and AUC (b) in lean (n=5) and obese (n=6) ZDF rats. Vertical lines show s.e.m.

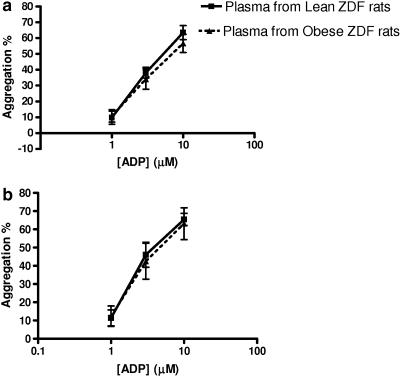

In vitro platelet aggregation (ZDF rats): effect of plasma

To determine whether the plasma environment exerted an effect on platelet aggregation responses to ADP, platelets isolated from lean and obese ZDF rats were each split into two aliquots. One aliquot of each platelet type was resuspended in plasma from lean ZDF rats and the other aliquot in plasma from obese ZDF rats. Aggregation responses were not different when either lean or obese ZDF rat platelets were suspended in plasma from obese ZDF rats as compared with that from lean ZDF rats (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of plasma on platelet aggregation in vitro in ZDF rats. ADP-induced aggregation responses in vitro of platelets from (a) lean and (b) obese ZDF rats following resuspension in plasma from lean and obese rats as indicated. Vertical lines show s.e.m., n=6 experiments per group.

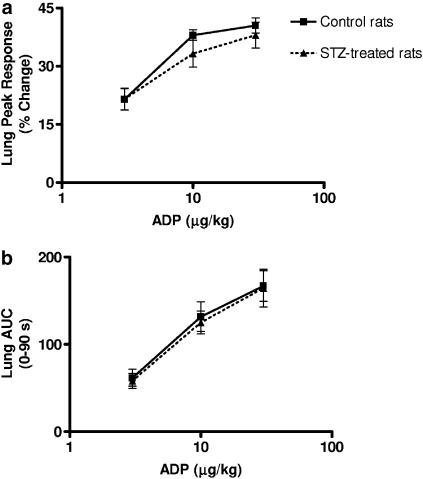

In vivo platelet aggregation (STZ rats)

STZ-treated rats at 21 days post-treatment were lighter than control Wistar rats (238±4 vs 299±4 g, P<0.05; n=18–23), had higher blood glucose concentrations (28.3±0.8 vs 6.3±0.2 mM, P<0.01; n=18–23) but had similar cholesterol levels (1.34±0.05 vs 1.30±0.05 mM; n=18–23). In vivo aggregation responses to ADP were determined using radiolabelled platelets as before. No difference was found in peak height or AUC between STZ-treated and control rats, following administration of ADP (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ADP-induced platelet aggregation responses in vivo in STZ-treated rats. Pulmonary platelet accumulation responses expressed as peak height (a) and AUC (b) in control (n=9) and STZ-treated (n=8) rats. Vertical lines show s.e.m.

To verify that the changes in radioactivity seen in these experiments truly reflected platelet accumulation and were not simply the result of changes in blood flow or distribution, additional experiments were performed in control Wistar rats substituting 111In-labelled erythrocytes for 111In-labelled platelets. Changes in erythrocyte-associated radioactivity recorded in the pulmonary vasculature were negligible, with peak responses of 2.8±1.0% following ADP 30 μg kg−1 (n=5).

We also wished to determine whether acute hyperglycaemia could affect platelet aggregation responses in vivo. To assess this, we infused glucose into normal Wistar rats to achieve a blood concentration of 18.5±3.8 mM. Elevation of blood glucose to this level had no observable effect on ADP-induced platelet aggregation (n=4 experiments; data not shown).

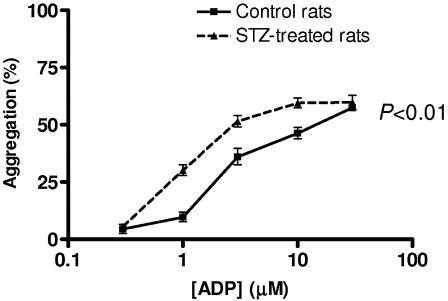

In vitro aggregation of isolated platelets (STZ rats)

ADP evoked a concentration-dependent aggregation in isolated platelets from both control and STZ-treated animals. ADP-induced aggregation responsiveness of platelets from STZ-treated rats was shifted to the left compared to that of platelets from control rats (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In vitro platelet aggregation in STZ-treated and control rats. ADP-induced aggregation responses in vitro of isolated platelets from STZ-treated and control Wistar rats. Vertical lines show s.e.m., n=6 experiments per group.

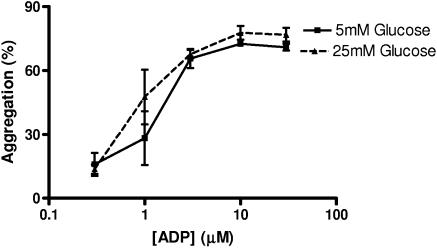

In vitro, ADP-induced aggregation responses of control Wistar rat platelets incubated with 25 mM glucose were unaffected as compared with platelets incubated with 5 mM glucose (Figure 6). Insulin, at two levels similar to those found in the blood of lean and obese ZDF rats, respectively (1 and 3 ng ml−1; see Table 1), had no effect on ADP-induced aggregation when incubated with control Wistar rat platelets in vitro (n=4 experiments; data not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of 25 mM glucose on platelet aggregation in vitro. ADP-induced aggregation responses in vitro of platelets from control Wistar rats incubated with 5 and 25 mM glucose. Vertical lines show s.e.m., n=4 experiments.

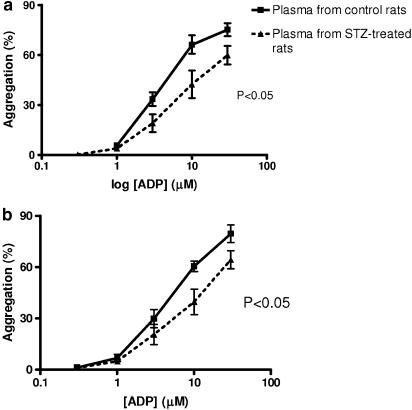

In vitro platelet aggregation (STZ rats): effect of plasma

The in vivo aggregation data suggested that platelets in STZ-treated animals are not more responsive to ADP than platelets in control animals. On the other hand, the in vitro data on isolated platelets suggested that platelets from STZ-treated rats are in fact more sensitive to ADP. In order to determine whether the plasma environment has an important influence on platelet responses in this model, platelet aggregation to ADP was measured in vitro using platelets from STZ-treated or control rats suspended in plasma from either STZ-treated or control rats. Platelets from controls, when suspended in plasma from controls, aggregated to a greater degree in response to ADP than when they were suspended in plasma taken from STZ-treated animals (Figure 7a). Similarly, platelets taken from STZ-treated animals aggregated more in response to ADP when suspended in plasma from controls than when suspended in plasma from STZ-treated rats (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Effect of plasma from STZ-treated or control Wistar rats on platelet aggregation in vitro. ADP-induced aggregation responses in vitro of platelets from control rats (a) and platelets from STZ-treated rats (b) suspended in plasma from either control or STZ-treated rats as indicated. Vertical lines show s.e.m., n=6 experiments per group.

Discussion and conclusions

The in vivo model of platelet accumulation used in this study has previously been validated (Page et al., 1982; Oyekan and Botting, 1986; May et al., 1990, 1991; Itoh et al., 1996) and provides a reliable and reproducible method of assessing platelet aggregation responses in vivo. It reflects true accumulation of platelets in the pulmonary vasculature that is not simply a consequence of changes in blood flow or distribution, as shown by the lack of effect of ADP when labelled erythrocytes were substituted for labelled platelets. Moreover, we have previously shown the presence histologically of platelet aggregates within the pulmonary vasculature at the time of peak accumulation of radiolabelled platelets (Dewar et al., 1984). The procedures of platelet isolation, radiolabelling and reinjection all have the potential to modify platelet functions; although there is the potential for such activation of donor (labelled) platelets to occur, following injection the donor platelets constitute only a very small fraction of the recipient animal's own platelets, and therefore measurement of their accumulation will in fact reflect responses occurring in the platelets of the recipient rather than of the donor animal (Oyekan and Botting, 1986).

Our results show that the platelets of obese ZDF rats are significantly more responsive to ADP-induced aggregation in vivo than are those of lean ZDF rats, in terms of both peak height and AUC responses. This is the first study to show increased platelet reactivity in ZDF rats and in particular to show that this is the case in vivo. In contrast, platelets from obese ZDF rats were no more responsive to ADP in vitro than platelets from lean ZDF rats, and – unlike in the case of STZ-treated rats – plasma from obese ZDF rats had no inhibitory effect on ADP-induced platelet aggregation in vitro.

In the STZ model, in vitro, platelets from STZ-treated animals were more responsive than those from control animals to ADP, in general agreement with similar studies carried out by others (Eldor et al., 1978; Dunbar et al., 1990; Takiguchi et al., 1991; Iida et al., 1993). In contrast, in vivo, platelets from STZ diabetic animals were similarly responsive to ADP as those from control rats. This finding is consistent with those reported by Takiguchi et al. (1991) who showed that photochemical thrombosis in vivo was slower in onset in STZ diabetic rats than in control animals. The discrepancy between these in vitro and in vivo observations may be explained by our in vitro plasma crossover studies, as we found that plasma from STZ diabetic animals has an inhibitory effect on aggregation of platelets from either group of animals, relative to plasma from control animals. These findings, which accord with previously published studies (Eldor et al., 1978; Takahashi et al., 1986; Judge et al., 1995), indicate that, even though platelets from STZ diabetic rats are intrinsically more sensitive to aggregating agents, this is counteracted by one or more factors, whose nature remains unclear, in their plasma which inhibit the aggregation response (or, conceivably, by the lack of factors which enhance the aggregation response in non-diabetic animals) of platelets. Such is not the case, however, in the ZDF model of diabetes.

Our study shows also that glucose per se is not responsible for the observed changes in platelet reactivity, as acute elevation of glucose levels, both in vitro and in vivo, had no significant effect on ADP-induced platelet responses. Moreover, our results suggest that a deficiency in NO cannot explain the increase in ADP aggregation responses seen in obese ZDF rats in vivo. Although NO is known to inhibit platelet recruitment, adhesion and aggregation, we found that obese ZDF rats actually exhibited higher NOx levels (which are a reflection of whole body NO production) than their lean counterparts, despite exhibiting increased ADP aggregation responses in vivo. It is possible that the increase in NO in these animals serves to partially offset the increase in ADP responses, although this is speculative at present.

A major focus of our study was to examine overall platelet responsiveness, and in particular to ascertain whether thoracic platelet accumulation (as a reflection of platelet thrombus formation in the pulmonary vasculature) in vivo is greater in diabetic than in control animals. The techniques used here do not allow us to draw any conclusions regarding more subtle and specific changes in platelet function, for example, alterations in platelet–vessel wall interactions. In future studies, it will be useful to determine changes in adhesion to both cultured vascular endothelial cells and to intact arterial segments, as well as in platelet expression of adhesion molecules and other markers of platelet activation (e.g. beta thromboglobulin, thrombomodulin, platelet factor 4), in diabetic and control animals.

In the present work, we have studied only aggregation responses to ADP, which is considered to be an important physiological mediator of platelet aggregation. It is released from dense granules of platelets, and acts principally through the platelet P2Y12 receptor (and also to a smaller degree the P2X1 and the P2Y1 receptors) to induce platelet activation and subsequent aggregation. Clinically, the P2Y12 receptor antagonist clopidogrel is widely used for the prevention of arterial thrombotic disease in patients at high risk of this; and evidence from large trials shows that clopidogrel is more effective in preventing thrombotic events in diabetic than in non-diabetic patients (Diener et al., 2005). This may possibly be related to an increase in ADP sensitivity of their platelets, although at present this is speculative. Nevertheless, this confirms the importance of ADP as a stimulus for thrombotic disease especially in diabetic patients. In future studies, it will be useful to determine whether the changes in ADP response documented in the present work are specific to ADP or whether they occur also with other pro-aggregatory agents such as collagen or thromboxane A2.

The results of this study show that, in an animal model of type II diabetes, platelet aggregation is increased in vivo, as determined by pulmonary accumulation of platelets in response to ADP. This may contribute to the increase in arterial thrombotic events seen in this condition, so that an increased ability of platelets to aggregate coupled with endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage combine to give rise to both macrovascular and microvascular disease. Our study also demonstrates that different models of diabetes may yield very different results; we found that, in the case of the STZ diabetic rat (a widely used model of diabetes, which is in fact a model of type 1 diabetes), in vivo platelet responses were not increased. These findings demonstrate that platelet responses may not necessarily be extrapolated from one animal model to diabetes more generally. Finally, our study demonstrates that in vitro platelet aggregation data do not necessarily reflect in vivo platelet responses, as exemplified by our data in both ZDF and STZ diabetic rats, and that the pathophysiological relevance of in vitro platelet aggregation results, in isolation, should be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Guy's and St Thomas' Charity and the British Heart Foundation for financial support. We are grateful to Dr P Lumb, Department of Chemical Pathology, St Thomas' Hospital, for measurement of plasma lipids and Drs R Chibber and B Mahmud, Centre for Cardiovascular Biology & Medicine, King's College London for measuring plasma AGEs.

Abbreviations

- AGE

advanced glycation end product

- CML

carboxymethyllysine

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOx

nitrate+nitrite

- PGE1

prostaglandin E1

- PPP

platelet-poor plasma

- PRP

platelet-rich plasma

- STZ

streptozotocin

- vWF

von Willebrand factor

- ZDF

Zucker Diabetic Fatty rat

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Cohen RA. Dysfunction of vascular endothelium in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 1993;87 (Suppl):V67–V76. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell JA, Nesto RW. Focus on prevention of ischemic events. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2181–2188. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vriese AS, Verbeuren TJ, van de Voorde J, Lameire NH, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:963–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar A, Archer CB, Paul W, Page CP, MacDonald DM, Morley J. Cutaneous and pulmonary histopathological responses to platelet activating factor (Paf-acether) in the guinea pig. J Pathol. 1984;144:25–34. doi: 10.1002/path.1711440104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener HC, Ringleb PA, Savi P. Clopidogrel for the secondary prevention of stroke. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:755–764. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.5.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar JC, Reinholt L, Henry RL, Mammen E. Platelet aggregation and disaggregation in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat: the effect of sympathetic inhibition. Dia Res Clin Pract. 1990;9:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0168-8227(90)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldor A, Merin S, Bar-On H. The effect of streptozotocin diabetes on platelet function in rats. Thromb Res. 1978;13:703–714. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(78)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman JE, Loscalzo J, Barnard MR, Alpert C, Keany JF, Michelson AD. Nitric oxide released from activated platelets inhibits platelet recruitment. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:350–356. doi: 10.1172/JCI119540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourani SMO, Cusack NJ. Pharmacological receptors on blood platelets. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:243–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida N, Iida R, Takeyama N, Tanaka T. Increased platelet aggregation and fatty acid oxidation in diabetic rats. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;30:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Cicala C, Douglas GJ, Page CP. Platelet accumulation induced by bacterial endotoxin in rats. Thromb Res. 1996;83:405–419. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge S, Mammen E, Dunbar JC. The effect of Streptozotocin induced diabetes on platelet aggregation as determined by impedence aggregometry and platelet secretion: a possible role for nitric oxide. J Assoc Acad Minor Physicians. 1995;6:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May GR, Crook P, Moore PK, Page CP. The role of nitric oxide as an endogenous regulator of platelet and neutrophil activation within the pulmonary circulation of the rabbit. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:759–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May GR, Herd CM, Butler KD, Page CP. Radioisotopic model for investigating thromboembolism in the rabbit. J Pharmacol Methods. 1990;24:19–35. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(90)90046-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan DM. Long term complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1676–1685. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306103282306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyekan OA, Botting JH. A minimally invasive technique for the study of intravascular platelet aggregation in anaesthetised rats. J Pharmacol Methods. 1986;15:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(86)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page CP, Paul W, Morley J. An in vivo model for studying platelet aggregation and disaggregation. Thromb Haemost. 1982;47:210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perper RJ, Oronsky AL, Blancuzzi V. An analysis of the specificity in pharmacological inhibition of the passive cutaneous anaphylaxis reaction in mice and rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;193:594–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queen LR, Ji Y, Goubareva I, Ferro A. Nitric oxide generation mediated by β-adrenoceptors is impaired in platelets from patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1474–1482. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radomski MW, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Characterization of the L-arginine:nitric oxide pathway in human platelets. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:325–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobol AB, Watala C. The role of platelets in diabetes related vascular complications. Diab Res Clin Prac. 2000;50:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrevia L, Mann GE. Dysfunction of the endothelial nitric oxide signalling pathway in diabetes and hyperglycaemia. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:423–452. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R, Morita I, Murota S, Ito H. Regulation of platelet aggregation and arachidonate metabolism in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Prostag Leukotr Med. 1986;25:123–129. doi: 10.1016/0262-1746(86)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi Y, Wada K, Matsuno H, Nakashima M. Effect of diabetes on photochemically induced thrombosis in femoral artery and platelet aggregation in rats. Thromb Res. 1991;63:445–456. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90231-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takiguchi Y, Wada K, Nakashima M. Effect of aldose reductase inhibitor on the inhibition of platelet aggregation induced by diabetic rat plasma. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;215:289–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vericel E, Januel C, Carreras M, Moulin P, Lagarde M. Diabetic patients without vascular complications display enhanced basal platelet activation and decreased antioxidant status. Diabetes. 2004;53:1046–1051. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby S, Holmes A, Loscalzo J. Platelets and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nursing. 2002;1:273–288. doi: 10.1016/s1474-5151(02)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winocour PD. Platelet abnormalities in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1992;41:23–31. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.s26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]