Abstract

The relaxin family peptides, although structurally closely related to insulin, act on a group of four G protein-coupled receptors now known as Relaxin Family Peptide (RXFP) Receptors. The leucine-rich repeat containing RXFP1 and RXFP2 and the small peptide-like RXFP3 and RXFP4 are the physiological targets for relaxin, insulin-like (INSL) peptide 3, relaxin-3 and INSL5, respectively. RXFP1 and RXFP2 have at least two binding sites – a high-affinity site in the leucine-rich repeat region of the ectodomain and a lower-affinity site in an exoloop of the transmembrane region. Although they respond to peptides that are structurally similar, RXFP3 and RXFP4 demonstrate distinct binding properties with relaxin-3 being the only peptide that can recognize these receptors in addition to RXFP1. Activation of RXFP1 or RXFP2 causes increased cAMP and the initial response for both receptors is the resultant of Gs-mediated activation and GoB-mediated inhibition of adenylate cyclase. With RXFP1, an additional delayed increase in cAMP involves βγ subunits released from Gi3. In contrast, RXFP3 and RXFP4 inhibit adenylate cyclase and RXFP3 causes ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Drugs acting at RXFP1 have potential for the treatment of diseases involving tissue fibrosis such as cardiac and renal failure, asthma and scleroderma and may also be useful to facilitate embryo implantation. Activators of RXFP2 may be useful to treat cryptorchidism and infertility and inhibitors have potential as contraceptives. Studies of the distribution and function of RXFP3 suggest that it is a potential target for anti-anxiety and anti-obesity drugs.

Keywords: H1 relaxin; H2 relaxin; H3 relaxin; INSL3; INSL5; RXFP1 (LGR7); RXFP2 (LGR8); RXFP3 (GPCR135, SALPR); RXFP4 (GPCR142, GPR100)

The discovery of the relaxin family peptides and their receptors

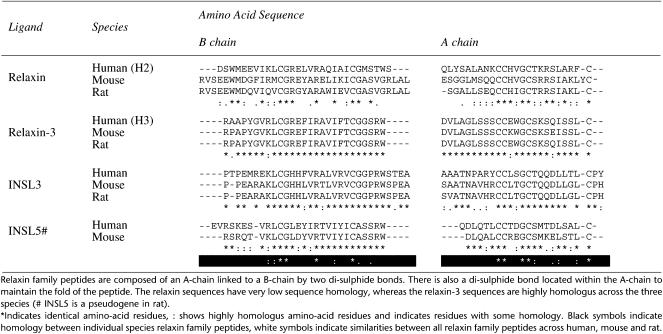

Relaxin was first identified in 1926 as a substance influencing the reproductive tract (Hisaw, 1926) and was subsequently found to be a peptide hormone with a two-chain structure similar to insulin (Bathgate et al., 2006c). Relaxin is a member of a family of peptide hormones that diverged from insulin, early in vertebrate evolution, to form the relaxin peptide family (Hsu, 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2005b). In recent years, several new members of this peptide family have been identified, either by differential cloning (insulin-like peptide 3 (INSL3), INSL4) or by screening of the EST (INSL5, INSL6) and genomic (relaxin-3) databases. The peptide family is encoded by seven genes in humans, the relaxin genes RLN1, RLN2 and RLN3 and the insulin-like (INSL) peptide genes INSL3, INSL4, INSL5 and INSL6. Although these peptides display relatively low primary amino-acid sequence homology (Table 1), phylogenetic analysis indicates that they evolved from a RLN3 ancestral gene (Hsu, 2003; Wilkinson et al., 2005b) before the emergence of fish and all have distinct expression profiles and biological functions (although the precise physiological roles of some peptides are yet to be determined). Thus, relaxin-3 is found predominantly in the brain and has putative actions as a neuropeptide (Burazin et al., 2002; Bathgate et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2005). INSL5 is widely found in the periphery, particularly in the kidney and colon, as well as in the brain and pituitary (Liu et al., 2005). Both of these peptides are highly conserved (Table 1), but have as yet not fully understood functions (Liu et al., 2003b, 2005). There has been a rapid expansion of this peptide family in mammals with the emergence of INSL3, INSL4 and INSL6. Insl3 is expressed in the testis and ovary, is essential for testicular descent in the male (Nef and Parada, 1999; Zimmerman et al., 1999) and additionally, has roles in oocyte maturation and male-germ cell survival (Kawamura et al., 2004). Insl4 and Insl6 are predominantly expressed in the placenta and testis, respectively, but their physiological roles are currently unknown. The term ‘neohormones' has been coined to describe such hormone systems specific to mammalian physiology, often addressing post-reproductive mammalian traits (Ivell and Bathgate, 2006). Relaxin and its receptor are often involved in pathologies that are considered to be age-related such as fibrosis, wound healing and responses to infarction. Post-reproductive survival can be considered advantageous to the species in terms of group dynamics and grandparent advantage (Ivell and Bathgate, 2006). The relaxin systems are therefore likely to represent important pharmacological targets in the clinical management of aging (Bathgate et al., 2006a).

Table 1.

Alignment of human, mouse and rat relaxin family peptides

Unlike humans and higher primates, most species possess only two relaxin genes, corresponding to RLN2 and RLN3. The product of the human RLN2 gene, human relaxin-2 (H2 relaxin) is the functional ortholog of the gene product from non-primate species that is termed ‘species' relaxin (e.g. rat relaxin; mouse relaxin). The function of the product of the human RLN1 gene, human relaxin-1 (H1 relaxin) is unknown, and indeed a native H1 relaxin peptide has yet to be isolated. Throughout this review the use of the term ‘relaxin' will refer to H2 relaxin or, where appropriate, non-primate ‘species' relaxin.

The receptors for relaxin (Hsu et al., 2002a), relaxin-3 (Liu et al., 2003a, 2003b), INSL3 (Overbeek et al., 2001; Hsu et al., 2002a; Kumagai et al., 2002) and INSL5 (Liu et al., 2005) were identified recently. Based on the hypothesized coevolution of peptide ligands and their receptors, there was a school of thought that believed that the receptors for relaxin and INSL3 were likely to be related to the known insulin receptors and as such be tyrosine kinases. However, there was also clear evidence that relaxin caused increases in cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) in reproductive tissues (Braddon, 1978; Cheah and Sherwood, 1980; Judson et al., 1980; Sanborn et al., 1980) and cell lines (Parsell et al., 1996). It is now known that in spite of their structural similarity, relaxin and insulin family peptides act through independent signalling pathways: the relaxin and insulin-like peptide groups activate the G-protein-coupled Relaxin Family Peptide Receptors (RXFPs), whereas the insulin group activates tyrosine kinases (Hsu et al., 2000). The RXFPs are a group of four receptors comprising the leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing RXFP1 and RXFP2 and the small peptide-like RXFP3 and RXFP4 (Bathgate et al., 2006a).

The characteristics of the LRR-containing RXFPs: RXFP1 and RXFP2

The relaxin receptor was identified following a systematic pursuit of ligands for mammalian orphan LRR-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGRs), that were discovered after a search of the expressed sequence tags database (Hsu et al., 2002a). A systematic screen of newly identified orphan receptors expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells revealed that two of the orphans, RXFP1 (LGR7) and RXFP2 (LGR8), responded to porcine relaxin by dose-dependent increases of cAMP, but failed to respond to insulin or insulin-like growth factor-I, indicating specificity for relaxin (Hsu et al., 2002a). Studies of phenotypic expression following mutation and inactivation of Insl3 and a transgenic insertional mutation in mouse chromosome 5 identified an orphan GPCR known as G-protein-coupled receptor affecting testis descent (Great) (Overbeek et al., 2001) and led to the identification of LGR8 (RXFP2) as the INSL3 receptor (Hsu et al., 2002a; Kumagai et al., 2002). INSL3 was found to bind RXFP2 with high affinity (Hsu et al., 2002a) and to cause cAMP stimulation and thymidine incorporation into the gubernaculum (Kumagai et al., 2002). Confirmation of the INSL3-RXFP2 ligand–receptor pairing was based upon the common phenotype of receptor- and ligand-null mice: cryptorchism or failure of the testis to descend during development (Kumagai et al., 2002). Based upon this discovery, the high similarity between RXFP1 and RXFP2, the similar expression patterns of Rxfp1 and relaxin genes and the higher affinity of relaxin for RXFP1 over RXFP2, RXFP1 was subsequently defined as the relaxin receptor (Hsu et al., 2002a).

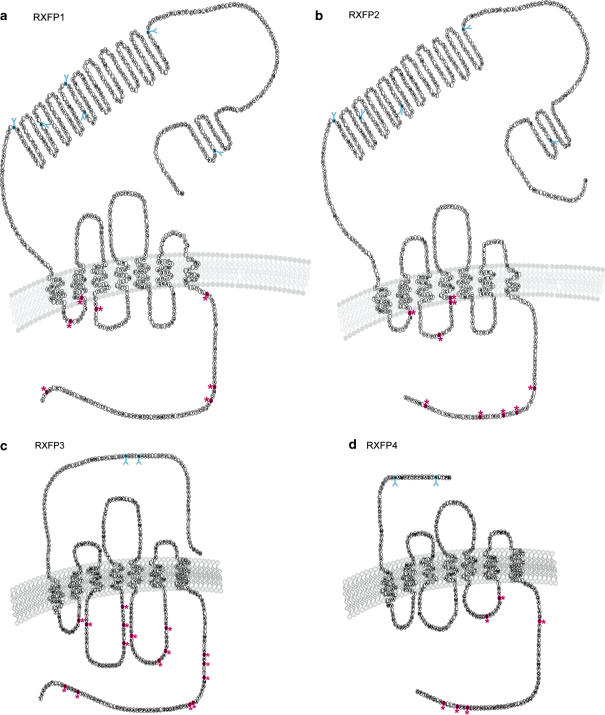

RXFP1 and RXFP2 belong to the glycoprotein hormone G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) subfamily known as the LGR subfamily (Ascoli et al., 2002). Studies of LGRs from different species have suggested that three subtypes of LGRs (A, B and C) originated during the early evolution of metazoans, with each subtype sharing a unique LRR domain (Hsu, 2003). Type A LGRs include the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR), the leutenising hormone receptor (LHR) and the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR). In mammals, the type B LGRs remain orphan GPCRs at present and consist of three members, LGRs 4–6. Finally, the type C LGRs have only two members, RXFP1 and RXFP2, and are characterized by a unique low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor class A module at the N-terminus, which is not present in the other sub-groups (Figure 1) (Hsu et al., 2000, 2002a).

Figure 1.

Structure of relaxin family peptide receptors (RXFP) 1–4. Snake plot diagram of predicted structure of (a) RXFP1, (b) RXFP2, (c) RXPF3 and (d) RXFP4. All receptors are seven TM spanning GPCRs. Major differences occur within the ectodomain. RXFP1 and RXFP2 have a large ectodomain containing LRRs and an LDL class A module. Contrastingly, RXFP3 and RXFP4 have shorter N-terminal tails than RXFP1 and RXFP2. Predicted N-linked glycosylation sites (Net-Gly 1.0 server) are indicated with Y and residues are colored blue, and predicted phosphorylation sites (Net-Phos 2.0 server) are indicated with * and colored in pink.

The characteristics of the small peptide-like RXFPs: RXFP3 and RXFP4

RXFP3 and RXFP4 were recently discovered (Matsumoto et al., 2000; Boels and Schaller, 2003; Liu et al., 2003a, 2003b) and are classified as family A GPCRs, with relatively short amino and carboxy-terminal tails compared with RXFP1 and RXFP2 (Figure 1). RXFP3 and RXFP4 have recently been identified as the receptors for the relaxin family peptides, relaxin-3 (Liu et al., 2003b) and INSL5 (Liu et al., 2005), respectively, and have many striking structural and functional differences from their relaxin- and INSL3-receptor counterparts (Figure 1). RXFP3 (also known as GPCR135 or SALPR) was identified in a human cortical cDNA library, with the highest sequence homology to somatostatin receptors (35% identity with type 5 receptor (SSTR5)) and angiotensin II receptors (31% identity with type 1 receptor (AT1)) (Matsumoto et al., 2000). Therefore, this receptor was first named Somatostatin and Angiotensin-Like Peptide Receptor (SALPR). Although the novel receptor did not bind either somatostatin or angiotensin II, it was hypothesized that it would be a peptide receptor owing to the homology observed between RXFP3 and the known small peptide receptors somatostatin type 5 and angiotensin II AT1 receptor, as well as, bradykinin, opioid and apelin receptors. RXFP4 (also known as GPCR142 or GPR100) was discovered by searching the human genomic database (Genbank) using the RXFP3 sequence (Boels and Schaller, 2003; Liu et al., 2003b). Owing to the sequence identity between human RXFP4 and human RXFP3 (43% identity) (Figure 2), it was suggested that these receptors share a ligand or at least have similar ligands.

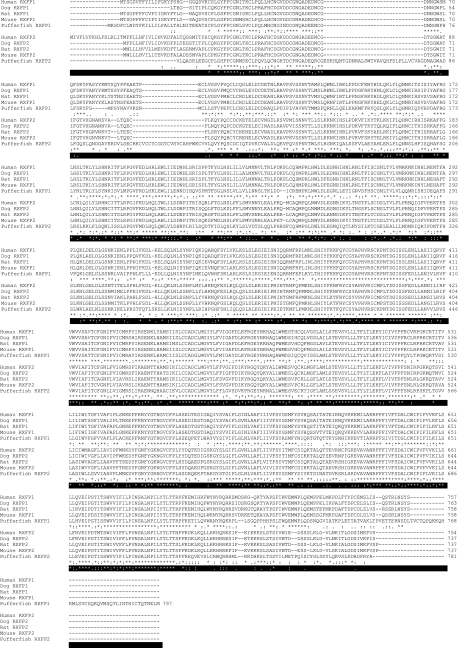

Figure 2.

Alignment of the primary amino-acid sequences of equivalent RXFP1 and RXFP2 from human, dog, rat, mouse and pufferfish. Human, dog, rat and mouse sequences were obtained from NCBI. Pufferfish sequences were obtained by searching the pufferfish genome with the relevant human sequence using BLASTp. *Indicates identical amino-acid residues, : shows highly homologous amino-acid residues and . indicates residues with some homology between RXFP1 species receptors or RXFP2 species receptors;  indicates identical amino-acid residues,

indicates identical amino-acid residues,  shows highly homologous amino-acid residues and

shows highly homologous amino-acid residues and  indicates residues with some homology between all receptors.

indicates residues with some homology between all receptors.

The ligand for RXFP3 was discovered by extracting peptides from rat organs, and testing these extracts against guanosine triphosphate (GTP)γS binding in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transiently expressing RXFP3. Brain peptide extracts showed the greatest GTPγS binding and were fractionated by HPLC, and the purified extracts tested and recycled until a single peptide was isolated (Liu et al., 2003b). This peptide was sequenced and found to contain peptide sequence analagous to human relaxin-3 (H3 relaxin) (Bathgate et al., 2003). The functionality of this peptide was confirmed by expressing full-length H3 relaxin cDNA in COS-7 cells and purifying the secreted peptide from the cell culture medium. The recombinant H3 relaxin was then tested on CHO cells transiently expressing RXFP3 where it caused GTPγS binding (Liu et al., 2003b). To determine whether RXFP3 and RXFP4 shared a common ligand, binding and functional assays were also carried out on RXFP4-expressing cells. H3 relaxin also competed for [125I]-H3 relaxin binding from COS-7 cells transiently expressing RXFP4 and caused GTPγS binding in CHO cells expressing the receptor, confirming that these two receptors responded to the same ligand.

Receptor evolution

Phylogenic analysis has shown that RXFP1 and RXFP2 emerged before the divergence of fish (Wilkinson et al., 2005a). Additionally, this subfamily of LGRs appears to have invertebrate origins, with two type C receptors in Drosophila melanogaster (FlyLGR3 and FlyLGR4), although these receptors were not deemed orthologs of RXFP1 or RXFP2, and there is no invertebrate relaxin peptide (Wilkinson et al., 2005a). Further, analysis of relaxin family peptides and their receptors suggests that RXFP1 and RXFP2 were ‘acquired' as relaxin family peptide receptors during mammalian evolution, and that the ancestral relaxin receptor–ligand system was RXFP3–relaxin-3 (Wilkinson et al., 2005a).

Multiple copies of both Rln3 and Rxfp3 have been identified in the genome of fugu fish and zebrafish. These multiple ligands and receptors probably exist due to gene duplication events (Wilkinson et al., 2005b), resulting from coevolution of the ligands and receptors. Mammals have only a single copy of the Rln3 and Rxfp3 genes, with the function of the other fish relaxin-3-like and RXFP3-like receptors replaced by the relaxin/INSL–LGR systems (Wilkinson et al., 2005a). This ligand-receptor coevolution theory is further supported by analysis of the Insl5 and Rxfp4 genes. The Insl5 and Rxfp4 genes in rats and dogs do not contain open reading frames and are therefore non-functional pseudogenes in these species (Wilkinson et al., 2005b). In addition, even though there is high homology observed between the rat and mouse Rxfp4 genes, the coding region of the rat Rxfp4 gene is interrupted by many deletions and insertions (Chen et al., 2005), further supporting the notion that these receptors and their ligands coevolved. Having retained the relaxin-3–RXFP3 system, it seems likely that this system serves a highly important brain function in mammals and other species, however the role of the INSL5-RXFP4 system remains to be defined.

Receptor conservation

Sequence analysis of RXFP1 and RXFP2 receptors shows high conservation from fish to mammals (Hsu et al., 2005). Human and rodent orthologs show greater than 90% sequence similarity (Hsu et al., 1998, 2002a, 2003). Similarly, the two pufferfish type C LGRs have greater than 77 and 70% sequence similarity in the transmembrane (TM) domain to human RXFP1 and RXFP2 respectively (Hsu et al., 1998). Additionally, human RXFP1 and RXFP2 share approximately 60% sequence identity (Hsu et al., 2002a) (Figure 2).

The genome sequences of human RXFP3 and RXFP4 consist of a single open reading frame of only one exon. Similarly, the mouse and rat Rxfp3 DNA sequences are intronless, and share 85 and 86% sequence identity, respectively, with the human receptor DNA sequence (Chen et al., 2005). TM domains -2, -3 and -6 are conserved between human rat and mouse RXFP3, with only TM-4 differing between the rat and mouse sequences (Chen et al., 2005). The rat Rxfp3 gene potentially codes two forms of RXFP3. Rat Rxfp3 has a second potential start codon upstream of the human and mouse start codon, that encodes an additional 7 amino acids (coding RXFP3-long), it also has the start codon found in the human and mouse sequences (RXFP3-short). Mouse RXFP3 is longer than human RXFP3 by an additional 3 amino acid residues between TM-5 and TM-6 (Figure 3). The mouse Rxfp4 sequence shares 74% sequence identity to the human RXFP4 gene. However, the mouse sequence is longer than the human sequence by 40 amino acids. The greatest difference between the receptor amino acid sequences is observed in the carboxy-terminal tail of mouse RXFP4, which is longer than that of the human RXFP4 (Figure 3)(Chen et al., 2005).

Figure 3.

Alignment of the primary amino-acid sequences of equivalent RXFP3 and RXFP4 from human, dog, chicken, rat, mouse and pufferfish. Human, dog, chicken, rat and mouse sequences were obtained from NCBI. Pufferfish sequences were obtained by searching the pufferfish genome with the relevant human sequence using BLASTp. Multiple pufferfish sequences were found, but only two were selected for alignment based upon highest homology score with the human sequence. *Indicates identical amino-acid residues, : shows highly homologous amino-acid residues, and . indicates residues with some homology between RXFP3 species receptors, or RXFP4 species receptors;  Indicates identical amino-acid residues,

Indicates identical amino-acid residues,  shows highly homologous amino-acid residues, and

shows highly homologous amino-acid residues, and  indicates residues with some homology between all receptors.

indicates residues with some homology between all receptors.

Functional genetics of RXFPs

The generation of Rxfp1 and Rxfp2 knockout animals has provided indications for the role of these receptors. Rxfp1−/− female mice have underdeveloped nipples and are unable to feed their pups and display prolonged parturition resulting in an increased number of dead pups upon delivery (Kamat et al., 2004; Krajnc–Franken et al., 2004). Some male Rxfp1−/− mice exhibited impaired spermatogenesis, azoospermia and thus a reduction in fertility (Krajnc–Franken et al., 2004). Rxfp1 knockouts of both sexes additionally display increased collagen accumulation and fibrosis around the bronchioles and blood vessels (Kamat et al., 2004). Rxfp2 knockout male mice exhibit cryptorchidism or failure of the testes to descend during development, progressive degeneration of spermatocytes, and thus a lack of spermatids and mature sperm (Overbeek et al., 2001; Gorlov et al., 2002). Although the phenotypes of these receptor knockouts are similar to their ligand counterparts, they are not identical (Nef and Parada, 1999; Nguyen et al., 2002; Du et al., 2003; Samuel et al., 2003, 2005a, 2005b).

Although Rxfp3 and Rxfp4 knockout mice have yet to be created, the study of the chromosomal location of these receptors and associated diseases may indicate a role for these receptors. Human RXFP3 is located on chromosome 5 at 5p15.1–5p14 (Matsumoto et al., 2000). A recent report suggests that polymorphisms occurring in the chromosomal region encoding RXFP3 may be responsible for a schizophrenic phenotype (Bespalova et al., 2005). However, sequencing the RXFP3 gene in these individuals did not reveal any relevant polymorphisms. Studies in rats indicate that RXFP3 may play a role in coordinating behavioral responses to stress and sensory information (Tanaka et al., 2005) and may additionally represent another important receptor affecting food intake (McGowan et al., 2005, 2006; Hida et al., 2006). Human RXFP4 is located on chromosome 1 at 1q21.2–1q21.3 (Boels and Schaller, 2003). The chromosomal region that encodes the locus of RXFP4 is also the locus determined for the axonal form of autosomal recessive Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy) (Bouhouche et al., 1999). However, further physiological studies have yet to be conducted in a species with Insl5 and Rxfp4 expression and so the role of this system remains undefined.

Receptor distribution

Northern blots of human tissue has identified mRNA for RXFP1 in ovary, uterus, placenta, testis, prostate, brain, kidney, heart, lung, liver, adrenal, thyroid, salivary glands, muscle, peripheral blood cells, bone marrow and skin (Hsu et al., 2002a; Luna et al., 2004; Mazella et al., 2004; Bathgate et al., 2006a). An additional shorter length receptor mRNA was also identified in oviduct, uterus, colon and brain (Hsu et al., 2000). Human RXFP1 protein expression has been identified by immunohistochemical analysis in uterus, cervix, vagina, nipple and breast (Kohsaka et al., 1998; Luna et al., 2004). Studies in mouse and/or rat tissues have additionally identified mRNA by Northern blot and lacZ-reporter expression in oviduct and intestine (Hsu et al., 2000; Krajnc-Franken et al., 2004).

RXFP2 mRNA expression in human occurs in the uterus, testis, brain, pituitary, kidney, thyroid, muscle, peripheral blood cells and bone marrow as determined by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Hsu et al., 2002b; Hombach-Klonisch et al., 2003; Mazella et al., 2004; Bathgate et al., 2006a). Additional expression was identified in rat and/or mouse in the ovary and gubernaculum as determined by RT-PCR, Northern blot analysis and/or in situ hybridization (Overbeek et al., 2001; Kubota et al., 2002; Kumagai et al., 2002; Kawamura et al., 2004).

In contrast to the widespread distribution of RXFP1 and RXFP2, RXFP3 mRNA is much more localized. Although not detectable by Northern blots, RXFP3 mRNA (or species equivalent) was identified by RT-PCR in human, mouse and rat brain and in testis (Liu et al., 2003b; Chen et al., 2005). In humans, the highest mRNA expression is detected in the substantia nigra, pituitary, hippocampus, spinal cord, amygdala, caudate nucleus, corpus callosum with low expression in the cerebellum (Matsumoto et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2003b). RT-PCR also revealed expression of RXFP3 in the testis (Liu et al., 2003b) and low expression in other peripheral tissues such as the adrenal glands, pancreas, salivary gland, placenta and mammary gland (Matsumoto et al., 2000). Furthermore, mouse and rat Rxfp3 mRNA was detected only in the brain and testes (Chen et al., 2005), supporting a role for relaxin-3 in the central nervous system, with the function in the testis remaining a mystery. Autoradiography using an INSL5 A-chain–H3 relaxin B-chain chimera and in situ hybridization with a full-length rat Rxfp3 riboprobe detected RXFP3 and Rxfp3 RNA in the olfactory bulb, sensory cortex, amygdala, thalamus, paraventricular nucleus, supraoptic nucleus and the inferior and superior colliculus (Sutton et al., 2005).

Northern blots conducted with RNA from human tissue revealed RXFP4 expression in the heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, liver and placenta (Boels and Schaller, 2003). Similar results were obtained by RT-PCR, with mRNA also detected in human colon, thyroid, salivary gland, prostate, thymus, testis and brain (Liu et al., 2003a). Mouse Rxfp4 has a wider profile of expression than human RXFP4 (Chen et al., 2005). RT-PCR detected mouse Rxfp4 mRNA in brain and testes as well as kidney, lung and spleen (Chen et al., 2005). However, a clear functional role for INSL5 and RXFP4 has yet to be described.

Splice variants of RXFP1 and RXFP2

One clear difference between the LRR-containing RXFP1 and RXFP2 and the small peptide-like receptors RXFP3 and RXFP4 is the presence of alternatively spliced isoforms of RXFP1 and RXFP2. Alternative splicing is a common occurrence within the LGR family, with reports of a number of splice variants of FSHR (Kraaij et al., 1998; Tena-Sempere et al., 1999), TSHR (Graves et al., 1992), LHR (Loosfelt et al., 1989; Misrahi et al., 1996; Nakamura et al., 2004) and LGR4 and LGR6 (Muda et al., 2005). Thus far, 29 splice variants of RXFP1 and RXFP2 have been identified, and these variants seem to be restricted to either TM-containing constructs or those that code for the truncated extracellular region only (Muda et al., 2005). Four of these identified variants have been studied in greater detail, and show a wide range of tissue expression, but were not able to bind either relaxin or INSL3 or to cause cAMP accumulation in response to either of these peptides (Muda et al., 2005). Although some isoforms were highly expressed, others were expressed at lower levels at the cell membrane, retained within the cell, or in the case of one variant, secreted, which raises interesting questions regarding endogenous regulation of the full-length RXFP1 receptor.

The secreted variant, termed RXFP1-truncate, has been studied in some detail and has also been identified in mouse, rat and pig (Scott et al., 2005b). RXFP1-truncate contains a deletion of exon 4, resulting in a reading frame shift and premature stop codon that halts protein translation after only 102 amino acids. This variant therefore consists of the receptor signal peptide, the LDL class A (LDLa) module, 33 residues of the LRR flanking sequence, and a non-homologous sequence of seven residues. Detailed analysis revealed that the RXFP1-truncate was secreted from transiently transfected HEK293T cells, and inhibited relaxin-stimulated cAMP signalling mediated by the full-length receptor (Scott et al., 2005b). Thus, this variant seemed to act as a functional antagonist. Expression of RXFP1-truncate was found to be increased during pregnancy in both mouse and rat, suggesting a functional role in causing localized antagonism of the actions of relaxin (Scott et al., 2005b). This is supported by functional splice variants of other LGRs. A natural splice variant of the related LHR, which is retained within the cell, has been found to modulate cell-surface expression of the full-length LHR (Nakamura et al., 2004).

It is clear that an extensive array of splice variants of these two receptors exist, although the function of many of these proteins is as yet unknown. Further research will reveal any functional significance of the variants and, specifically, whether they have an important role in the regulation of RXFP1 and RXFP2 in vivo.

Receptor structure

The RXFP1 and RXFP2 ectodomain is distinguished from other LGRs by a unique LDLa module at the amino terminus. Receptors lacking the LDLa module were found to bind relaxin peptides, but were unable to affect cAMP accumulation (Scott et al., 2006). Thus, the LDLa region appears essential for the cAMP signalling properties of RXFP1 and RXFP2. The LDLa module is followed by an alternatively spliced flanking region, leading into the 10 LRRs. Essential to the structure of the LRRs are cysteine-rich regions that act to form ‘caps' at each end of the LRRs (Kobe and Kajava, 2001). Modelling of the LRR region on the porcine ribonuclease inhibitor (another protein with LRRs) showed the expected parallel pleated sheets inside, and helicies on the outside of a horseshoe-shaped structure (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005b). The ectodomain of these receptors (specifically the LRR region) is important for the binding of glycoprotein hormones (Kobe and Deisenhofer, 1993), in contrast to the binding of many GPCRs that respond to small biogenic amines, which occurs within the TM region. The relatively large ectodomain connects to the seven- TM-spanning regions, and finally the C-terminal tail.

Analysis of the primary amino-acid sequence of these two receptors (Figure 1) predicts that the receptors will be N-terminally glycosylated (NetGlyC 1.0 Server), and contain a number of potential phosphorylation sites in the intracellular loops and C-terminal tail (NetPhos 2.0 Server). The functional relevance of such predictions however, is yet to be determined for these two receptors. However Ciphergen surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization–mass spectrometry analysis of an ectodomain-only RXFP1 construct revealed a broad mass spectrum consistent with this receptor being highly glycosylated (Yan et al., 2005).

Unlike the LRR-containing relaxin receptors, RXFP3 and RXFP4 have relatively short extracellular domains. The human RXFP3 exon encodes a protein of 469 amino acids, the mouse 472 and the rat 476 residues. The RXFP4 sequence is shorter, with 374 amino acids in human RXFP4 and 408 in mouse RXFP4, although the functional consequences of these differences have yet to be investigated.

Analysis of the primary amino-acid sequence (Figure 1) shows that all four receptors possess the seven hydrophobic helices thought to span the plasma membrane. The receptors are also predicted to be N-terminally glycosylated (NetGlyC 1.0 Server) that may be important for cellular localization or function in ligand recognition. There are also many putative phosphorylation sites in the intracellular loops and carboxy-terminal tails (NetPhos 2.0 Server) that may be important for regulation of receptor signaling and internalization, although this has yet to be established.

Binding characteristics of RXFP1 and RXFP2 receptors

Numerous species relaxins have since been shown to bind and activate both RXFP1 and RXFP2. This has allowed establishment of a rank order of affinity (Table 2) for the different species relaxins and INSL3, which should potentially allow the isolation of essential residues within these peptides that are required for high-affinity binding. Eventually this knowledge should aid in the design of small molecular mimetics and potential pharmacological tools and therapeutics. At human RXFP1, the rank order of affinity was determined as H2 relaxin=rhesus monkey relaxin>porcine relaxin>H1 relaxin>H3 relaxin>rat relaxin>>INSL3 (no binding) (Sudo et al., 2003; Halls et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2005a; Bathgate et al., 2006b).

Table 2.

Affinities and potencies of relaxin family peptides for human relaxin family peptide receptors 1–4

|

H1 relaxin |

H2 relaxin |

H3 relaxin |

hINSL3 |

hINSL5 |

Porcine relaxin |

Rhesus monkey relaxin |

Rat relaxin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | B | F | |

| RXFP1 | 8.84a | 9.10a | 9.35b | 10.60a | 7.48d | 7.72d | 5.80d | 5.40a | 8.56b | 9.09b | 9.39b | 9.76b | 7.27b | 7.70b | ||

| 10.21b | 9.57b | 8.01b | 8.19a | 5.97a | ||||||||||||

| 10.04d | 9.42c | 8.50a | 8.82g | |||||||||||||

| 9.70h | 9.21d | 8.70g | ||||||||||||||

| 10.00h | ||||||||||||||||

| RXFP2 | 8.83a | 8.30b | 7.72b | 6.97a | >5a | 9.66a | 9.40a | 7.87b | 8.05b | 7.81b | 5.40b | No bindng | ||||

| 8.82h | 7.94a | 9.68b | 8.16b | |||||||||||||

| 9.07d | 8.04d | 9.72d | 9.24c | |||||||||||||

| 9.27b | 8.80h | 9.85h | 8.38d | |||||||||||||

| 9.80h | ||||||||||||||||

| RXFP3 | 9.38e | 9.25a | 6.30h | Antag h | ||||||||||||

| 9.40h | 9.38g | |||||||||||||||

| 9.52g | 9.46f | |||||||||||||||

| 9.52h | ||||||||||||||||

| RXFP4 | 8.84e | 8.96i | 8.82h | 8.92h | ||||||||||||

| 8.92i | 9.04g | |||||||||||||||

| 8.96g | ||||||||||||||||

| 9.00h | ||||||||||||||||

Abbreviations: H1, human gene 1 relaxin; H3, human gene 2 relaxin; H3, human gene 3 relaxin; INSL, insulin-like peptide; RXFP, relaxin family peptide receptor.

Competition-binding studies (B) with RXFP1 and RXFP2 were conducted with [33P]-H2 relaxin (B33) and those with RXFP3 and RXFP4 with [125I]-H3 relaxin. Functional studies (F) with RXFP1 and RXFP2 examined cAMP accumulation and those with RXFP3 and RXFP4 examined inhibition of forskolin stimulated cAMP accumulation.

Bathgate et al. (2006) (pKi and pEC50 (cAMP)).

Halls et al. (2005) (pKi and pEC50 (cAMP)).

Halls et al. (2006) (pEC50 (cAMP)).

Sudo et al. (2003) (pIC50 and pEC50 (cAMP)).

Chen et al. (2005) (pIC50).

Liu et al. (2003) (pEC50 (cAMP inhib)).

Liu et al. (2005) (pKi and pEC50 (CRE reporter, β-gal)).

Liu et al. (2005) (pKi and pEC50 (cAMP). NB [125I]-INSL3 for RXFP2).

Liu et al. (2003) (pKi and pEC50 (cAMP)).

At RXFP2, INSL3>H1 relaxin=H2 relaxin>porcine relaxin=rhesus monkey relaxin>>H3 relaxin=rat relaxin (no binding) (Halls et al., 2005; Bathgate et al., 2006b). Interestingly, the relative binding affinity of relaxin family peptides for these receptors is usually reflected in their relative ability to increase cAMP accumulation (Halls et al., 2005).

The lack of INSL3 binding at RXFP1 and lack of rat relaxin binding at RXFP2 has been confirmed in an in vivo setting using transgenic animals (Bogatcheva et al., 2003; Kamat et al., 2004; Feng et al., 2006). This additionally suggests that the H2 relaxin interaction with RXFP2 may be a species-specific event (Halls et al., 2005). In terms of other species receptors, there is less binding affinity data available (for summary see Bathgate et al., 2006b). The only major differences identified thus far include a higher affinity of the relevant species relaxin for its receptor and the aforementioned inability of rat relaxin to bind rat RXFP2 (Halls et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2005a).

Recent studies have provided evidence that RXFP1 and RXFP2 have at least two ligand-binding sites. Work with chimeric receptors utilized the specificity of H3 relaxin for RXFP1 (over RXFP2) and revealed that the peptide requires interaction with both the ectodomain and exoloop 2 of the TM domain of RXFP1 for full binding and cAMP signalling (Sudo et al., 2003). This was subsequently confirmed as a characteristic of both receptors. Both RXFP1 and RXFP2 contain two ligand-binding sites: a high-affinity site within the ectodomain, and a lower-affinity site within the TM region (Halls et al., 2005). This was supported by studies of cAMP accumulation: the high-affinity ectodomain site induced cAMP accumulation with higher efficiency than the low affinity TM site (Halls et al., 2005). Studies with chimeric and truncated receptors confirmed that the interaction between these sites is essential for optimal binding and signal transduction, although the precise nature of the interaction appears to vary dependent upon the peptide in question (Halls et al., 2005).

Subsequent molecular modelling of the LRR region of RXFP1 revealed a likely binding cassette for relaxin, which occurs at an angle of 45° across five of the parallel LRRs (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005b). Close analysis of these LRRs revealed that relaxin binding occurs through synchronized chelation of the two arginines present in the relaxin B-chain (B13 and B17: part of the relaxin-binding motif) through neutralization of charge from acidic groups within the concave face of the LRR of the receptor, and generation of a hydrogen bonding network (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005b). This is stabilized by a hydrophobic interaction between isoleucine (B20) and a cluster of tryptophan, isoleucine and leucine in neighboring LRRs in the receptor (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005b). It was found that deletion of any of these features in the receptor removed relaxin binding (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005b). These residues are also present on RXFP2 and are also probably important in the binding of relaxin to this receptor (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2006).

Despite RXFP2 containing all of the residues required for the binding of relaxin to RXFP1, a number of recent studies have suggested that they are not essential for INSL3 binding. Initial mutational analyses of the binding of INSL3 to RXFP2 revealed that the minimum length of the B-chain required for receptor binding was contained by residues 11–27 (Del Borgo et al., 2006). Interestingly, enhancement of α-helical content of this shortened mimetic using disulfide linkages has generated a synthetic antagonist of RXFP2, that when administered into the testis of rats caused a decrease in testis weight, probably owing to inhibition of germ-cell survival, suggesting functionality in vivo (Del Borgo et al., 2006). Subsequent studies have focused upon the specific residues of INSL3 which control its interaction with RXFP2, and revealed three essential INSL3 residues that interact strongly with the receptor, arginine (B16), valine (B19) and tryptophan (B27), due to these three residues forming a contiguous area (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2006). This requires flexibility in the B-chain C-terminal region, provided by a ‘hinge' sequence of glycine–glycine–proline (B23–B25) (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2006). Thus, at RXFP2, relaxin and INSL3 are likely to bind to different, but overlapping sites of the receptor, as one peptide is able to compete for binding with the other. Another group has recently provided a more detailed model of INSL3 binding to its receptor, using NMR together with mutational analysis of INSL3 (Rosengren et al., 2006). In this model, the initial, primarily electrostatic interaction between INSL3 and RXFP2 is dependent upon the B-chain residues histidine (B12), arginine (B16) and arginine (B20). A repositioning of the flexible B-chain C-terminus then occurs, which allows INSL3 to effectively ‘lock-in' to the receptor by securing the essential tryptophan (B27).

Interestingly, the A-chain of INSL3 does not appear to contribute to binding (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2006), but nevertheless does appear to be essential for signal transduction. Mutational analysis of this peptide revealed that deletion of six residues from the N-terminus of the A-chain generated a peptide which still had activity, whereas deletion of more than six residues, up to the first cysteine (A10), yielded a peptide which retained binding, but was unable to generate cAMP (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005a). These studies have generated a number of specific high-affinity competitive inhibitors of RXFP2 (Bullesbach and Schwabe, 2005a) that will be valuable tools in the search for the functions of this receptor. It is unknown whether the cAMP signalling of RXFP1 is also dependent upon interaction with the N-terminus of relaxin

Binding characteristics of RXFP3 and RXFP4 receptors

Although they respond to peptides that may be structurally quite similar, the pharmacological characteristics of the RXFP3 and RXFP4 receptors are quite distinct from those of RXFP1 and RXFP2. Characterization of human RXFP3 expressed transiently in green African monkey kidney (COS-7) cells revealed that the receptor binds relaxin-3 at a site that shows peptide competition only with H3 relaxin and the H3 relaxin B-chain, but not with porcine relaxin, INSL3 or the H3 relaxin A-chain (Liu et al., 2003b). Similarly, mouse RXFP3 and the two forms of rat RXFP3 expressed in COS-7 cells, both bound human relaxin-3 (Chen et al., 2005). This binding profile is unique to RXFP3 as RXFP1 and RXFP2 both show binding to many relaxin family peptides.

Interestingly, human RXFP4 also bound [125I]-relaxin-3 with high-affinity (Liu et al., 2003a), and there was competition by relaxin-3 and the B-chain of relaxin-3 (Liu et al., 2003a) (Table 2). COS-7 cells transiently expressing monkey, mouse, bovine or porcine RXFP4 also bound human relaxin-3 with high-affinity (Chen et al., 2005). Bovine RXFP4 showed the highest affinity for human relaxin-3, followed by human, monkey and porcine, with mouse displaying the lowest affinity for this peptide (Chen et al., 2005). As mentioned above, evolutionary tracing of RXFP4 and INSL5 indicated that INSL5 was the physiological ligand for RXFP4, rather than relaxin-3 (Wilkinson et al., 2005c). When tested in vitro, INSL5 bound to RXFP4 with an affinity equal to that of relaxin-3 (Liu et al., 2005). INSL5 was also tested for its affinity to RXFP1, RXFP2 and RXFP3 and competed for [125I]-relaxin-3 binding to RXFP3, but with a much lower-affinity than relaxin-3 (Table 2). INSL5 failed to compete for [125I]-relaxin-3- or [125I]-INSL3-binding at RXFP1 or RXFP2, respectively, suggesting that INSL5 is a ligand for RXFP4 (Liu et al., 2005).

Signal transduction mechanisms activated by RXFP receptors

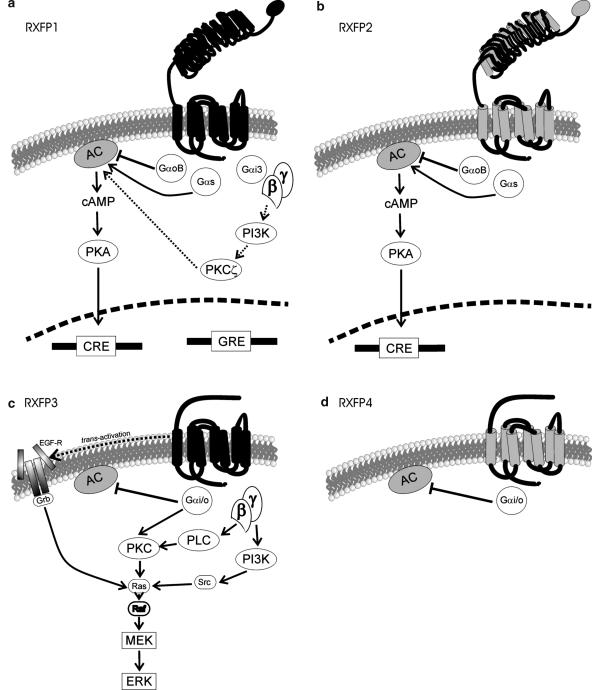

Owing to tracing of both type A LGRs and the co-evolved genes encoding glycoprotein hormone subunits to both nematodes and insects, Hsu et al. (2000) concluded that the three subfamilies of LGRs evolved before the emergence of vertebrates and nematodes. Thus, the type C LGR signalling pathways mediated by RXFP1 and RXFP2 represent one of the earliest forms of GPCR signalling (Bathgate et al., 2006a) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Signalling pathways activated by the RXFPs. (a) RXFP1 is activated primarily by relaxin and appears to signal mainly via cAMP. Initially RXFP1 increases cAMP accumulation via Gαs and negatively modulates this via GαoB. These two pathways combined to affect CRE transcription. With time (dotted lines) RXFP1 recruits Gαi3 which activates the Gβγ-PI3K-PKCζ pathway to further increase cAMP. RXFP1 also appears to activate GRE transcription (and possibly GR) by a currently unknown mechanism. (b) RXFP2 is activated by INSL3 (in addition to some relaxins, although this is species-specific) and both activates and negatively modulates cAMP accumulation by Gαs and GαoB respectively, which leads to effects upon CRE transcription. (c) RXFP3 is activated by relaxin-3 and inhibits forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation. This receptor also activated ERK1/2 by a mechanism which requires receptor internalization or movement into lipid-rich signalling platforms, activation of PTX sensitive G proteins, PKC as well as Raf and MEK1/2. PI3K activation and EGF receptor transactivation (if expressed in the cell) are required for full ERK1/2 phosphorylation to occur, however about 50% of ERK1/2 will still be phosphorylated if these entities are blocked with specific inhibitors, (d) RXFP4 is activated by INSL5 and is also coupled to the inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation.

On original characterization of these two receptors, constitutively active mutants of both RXFP1 and RXFP2 (TM helix 6: Asp 637 Tyr) were found to signal by increased cAMP accumulation in a ligand-independent manner (Hsu et al., 2000, 2002b). Thus, a major signalling pathway activated by these receptors appears to be the Gs–cAMP–protein kinase (PK)A pathway. Consequently, much research since has focused upon cAMP accumulation modulated by these two receptors.

Recent studies have identified a biphasic time course of cAMP accumulation following RXFP1 stimulation by relaxin (Nguyen et al., 2003; Halls et al., 2006). The initial phases of the response (lasting until approximately 10–15 min following stimulation of the receptor) involves cAMP accumulation activated by Gαs and an inhibition mediated by GαoB (Halls et al., 2006). The second, delayed phase of the response additionally involves recruitment of Gαi3 proteins, which release Gβγ subunits (Halls et al., 2006). These G-βγ subunits then activate phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)-kinase (Nguyen et al., 2003), which activates and translocates PKCζ, (an atypical PKC isoform) to the cell membrane, and finally activates adenylate cyclase to further stimulate the production of cAMP (Nguyen and Dessauer, 2005).

Interestingly, the cAMP signalling pathways activated following RXFP2 stimulation appear, at present, to be less complex. Thus, there is no evidence for a biphasic accumulation of cAMP following receptor activation. Stimulation of this receptor by INSL3 (or H2 relaxin) leads to accumulation of cAMP accumulation through Gs, and an inhibition of cAMP accumulation mediated by GαoB and Gβγ subunits (Halls et al., 2006). In cell systems endogenously expressing RXFP2, the receptor appears to mediate a variety of responses. In gubernacular cells, like HEK293T-expression systems, stimulation with INSL3 causes an increase in cAMP (Kumagai et al., 2002). However, and conversely, in both male and female germ cells and oocytes, stimulation of RXFP2 causes an inhibition of cAMP mediated although pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G proteins (Kawamura et al., 2004). Thus, it appears that the signalling outcomes mediated by these receptors vary greatly depending on cell types and may be based upon the expression levels of the relevant G proteins involved.

For RXFP1, there is also evidence for activation of other signalling pathways in response to relaxin. In THP-1 and human endometrial stromal cells, both of which endogenously express RXFP1, there is evidence for tyrosine kinase or mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent cAMP accumulation (Bartsch et al., 2001), which may involve relaxin-mediated inhibition of a phosphodiesterase (Bartsch et al., 2004). However, this is not always observed, and some studies show no effect of phosphodiesterase inhibition upon the RXFP1-mediated cAMP response (Nguyen et al., 2003). Apart from cAMP-related signalling, a number of cell types that express RXFP1 rapidly activate ERK1/2 (<5 min) on relaxin stimulation, including human endometrial stromal cells, THP-1 cells and primary cultures of human coronary artery and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (Zhang et al., 2002). There is also evidence for relaxin-mediated increases in nitric oxide both acutely and chronically, although the exact mechanism of this increase or whether this is directly or indirectly linked to RXFP1 is still unclear (Nistri and Bani, 2003; Conrad and Novak, 2004). More recently, relaxin was reported to interact with the glucocorticoid receptor, although whether this requires RXFP1 or is an independent event is also uncertain (Dschietzig et al., 2004).

In contrast to RXFP1 and RXFP2, functional characterization of RXFP3 and RXFP4 showed that they do not stimulate cAMP production (Liu et al., 2003a, 2003b). Instead, RXFP3 and RXFP4 were shown to be functionally coupled to inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation (Liu et al., 2003a, 2003b). These receptors were also cotransfected into HEK293 cells with either Gαi/q5 chimeric G protein (RXFP3) or Gα16 (RXFP4) and switched their signalling to calcium mobilization (Liu et al., 2003a, 2003b). Mouse and rat RXFP3 were also characterized using GTPγS and calcium mobilization assays and relaxin-3 had similar potency at these receptors as reported for the human receptor (Chen et al., 2005). Additionally, human RXFP3 increased extracellular acidification in the cytosensor microphysiometer when stimulated with H3 relaxin, but not by H2 relaxin, porcine relaxin or INSL3 (van der Westhuizen et al., 2005).

RXFP3 is strongly coupled to ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CHO-K1 and HEK293 cells stably expressing the receptor (van der Westhuizen et al. (2007), submitted). The response to H3 relaxin is rapid and transient (2–5 min) with a concentration dependent activation observed at 5 min of H3 relaxin stimulation. The mechanism of ERK1/2 activation absolutely requires receptor internalization/movement of RXFP3 into lipid rich signalling platforms as ERK1/2 activation is abolished by hypertonic sucrose which disrupts the formation of clathrin-coated pits required for receptor internalization (Heuser and Anderson, 1989). ERK1/2 activation also occurs only by activation of a PTX-sensitive G protein, activation of a novel and/or atypical PKC and is Raf- and MEK1/2-dependent. RXFP3 partially activates ERK1/2 by a pathway that includes PI3K and Src tyrosine kinase, as in the presence of inhibitors of these pathways, ERK1/2 activation was blocked by 50%. The results in the two cell lines differed only slightly; ERK1/2 activation occurred in part by the transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptors in HEK cells but not in CHO cells. Additionally, a greater portion of the ERK1/2 response was reliant on PLCβ in HEK compared with CHO cells.

In CHO cells transiently expressing human RXFP4, human relaxin-3 increases GTPγS binding (Liu et al., 2003a) in a manner similar to that observed in CHO cells expressing monkey and porcine RXFP4. GTPγS binding was higher in bovine but lower in mouse RXFP4 cells, reflecting the relative potency of human relaxin-3 in receptor-binding studies with these different species RXFP4 receptors (Chen et al., 2005). Further functional characterization of these species RXFP4 receptors transiently expressed in HEK293 cells with the promiscuous G protein Gα16 showed that bovine, porcine, monkey and human RXFP4 all behaved in a similar manner, whereas no functional response was detected in cells expressing the mouse RXFP4 (Chen et al., 2005). This may represent differences in the mammalian versus the rodent RXFP4 receptors, but may also represent an inability of mouse RXFP4 to couple to Gα16 in vitro.

Although relaxin was discovered 80 years ago, it is only in the last 5 years that its cognate receptor RXFP1 has been isolated together with three other receptors (RXFP2–4) that respond to relaxin family peptides. Recent studies are increasing our understanding of the ways in which relaxin and INSL3 interact with their respective receptors and of the signalling pathways they activate. Drugs acting at RXFP1 have potential for the treatment of a wide variety of diseases involving tissue fibrosis such as cardiac and renal failure, asthma and scleroderma and may also be useful to facilitate embryo implantation. Activators of RXFP2 may be useful for the treatment of cryptorchidism and infertility and inhibitors may be effective contraceptives. Although at an earlier stage of understanding, the studies of the distribution and function of RXFP3 suggest that this receptor may have potential for the development of anti-anxiety and anti-obesity drugs. The isolation of the four relaxin family peptide receptors has provided valuable tools for the study of the way in which ligands interact with the receptors and for identifying the signalling pathways that are utilized. Receptor antagonists are now beginning to emerge that will allow the elucidation of further physiological roles for these receptors.

Acknowledgments

ML Halls is an Australian Postgraduate scholar and recipient of a Monash University Faculty of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences Excellence Award. ET van der Westhuizen is the recipient of a NH&MRC Dora Lush (Biomedical) Post Graduate Scholarship. This work was supported in part by NH&MRC Block Grant Reg Key 983001 to the Howard Florey Institute, NH&MRC Project Grant 300012 (RADB and RJS) and ARC Linkage Grant LP0560620 (RJS and RADB).

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- H2 relaxin

human gene 2 relaxin

- H3 relaxin

human gene 3 relaxin

- INSL3

insulin-like peptide 3

- INSL5

insulin-like peptide 5

- LGR

leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor

- LRR

leucine-rich repeats

- RXFP1

relaxin family peptide receptor 1 (LGR7)

- RXFP2

relaxin family peptide receptor 2 (LGR8)

- RXFP3

relaxin family peptide receptor 3 (GPCR135, SALPR)

- RXFP4

relaxin family peptide receptor 4 (GPCR142, GPR100)

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Ascoli M, Fanelli F, Segaloff DL. The lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor, a 2002 perspective. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:141–174. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch O, Bartlick B, Ivell R. Relaxin signalling links tyrosine phosphorylation to phosphodiesterase and adenylyl cyclase activity. Mol Human Reprod. 2001;7:799–809. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.9.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch O, Bartlick B, Ivell R. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibition synergizes with relaxin signaling to promote decidualization of human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:324–334. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate RA, Ivell R, Sanborn BM, Sherwood OD, Summers RJ. International Union of Pharmacology LVII: recommendations for the nomenclature of receptors for relaxin family peptides. Pharmacol Rev. 2006a;58:7–31. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate RA, Lin F, Hanson NF, Otvos L, Jr, Guidolin A, Giannakis C, et al. Relaxin-3: improved synthesis strategy and demonstration of its high-affinity interaction with the relaxin receptor LGR7 both in vitro and in vivo. Biochemistry. 2006b;45:1043–1053. doi: 10.1021/bi052233e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate RA, Samuel CS, Burazin TC, Gundlach AL, Tregear GW. Relaxin: new peptides, receptors and novel actions. Trends Endocrin Metab. 2003;14:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate RAD, Hsueh AJW, Sherwood OD.Physiology and molecular biology of the relaxin peptide family Knobil and Neill's Physiology of Reproduction 2006cAcademic Press, New York; In: Neill JD (ed)3rd edn [Google Scholar]

- Bespalova IN, Angelo GW, Durner M, Smith CJ, Siever LJ, Buxbaum JD, et al. Fine mapping of the 5p13 locus linked to schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder in a Puerto Rican family. Psychiatr Genet. 2005;15:205–210. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200509000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boels K, Schaller HC. Identification and characterisation of GPR100 as a novel human G-protein-coupled bradykinin receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:932–938. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogatcheva NV, Truong A, Feng S, Engel W, Adham IM, Agoulnik AI. GREAT/LGR8 is the only receptor for insulin-like 3 peptide. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:2639–2646. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhouche A, Benomar A, Birouk N, Mularoni A, Meggouh F, Tassin J, et al. A locus for an axonal form of autosomal recessive Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease maps to chromosome 1q21.2–q21.3. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:722–727. doi: 10.1086/302542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddon SA. Relaxin-dependent adenosine 6′,5′-monophosphate concentration changes in the mouse pubic symphysis. Endocrinology. 1978;102:1292–1299. doi: 10.1210/endo-102-4-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullesbach EE, Schwabe C. LGR8 signal activation by the relaxin-like factor. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:14856–14890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullesbach EE, Schwabe C. The trap-like relaxin-binding site of LGR7. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:14051–14056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullesbach EE, Schwabe C. The mode of interaction of the relaxin-like factor (RLF) with the leucine-rich repeat G protein-activated receptor 8. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26136–26143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burazin TC, Bathgate RA, Macris M, Layfield S, Gundlach AL, Tregear GW. Restricted, but abundant, expression of the novel rat gene-3 (R3) relaxin in the dorsal tegmental region of brain. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1553–1557. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah SH, Sherwood OD. Target tissues for relaxin in the rat: tissue distribution of injected 125I-labeled relaxin and tissue changes in adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate levels after in vitro relaxin incubation. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1203–1209. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-4-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Kuei C, Sutton SW, Bonaventure P, Nepomuceno D, Eriste E, et al. Pharmacological characterization of relaxin-3/INSL7 receptors GPCR135 and GPCR142 from different mammalian species. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:83–95. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KP, Novak J. Emerging role of relaxin in renal and cardiovascular function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R250–R261. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00672.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Borgo MP, Hughes RA, Bathgate RA, Lin F, Kawamura K, Wade JD. Analogs of insulin-like peptide 3 (INSL3) B-chain are LGR8 antagonists in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13068–13074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dschietzig T, Bartsch C, Stangl V, Baumann G, Stangl K. Identification of the pregnancy hormone relaxin as glucocorticoid receptor agonist. FASEB J. 2004;18:1536–1538. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1120fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XJ, Samuel CS, Gao XM, Zhao L, Parry LJ, Tregear GW. Increased myocardial collagen and ventricular diastolic dysfunction in relaxin deficient mice: a gender-specific phenotype. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Bogatcheva NV, Kamat AA, Truong A, Agoulnik AI. Endocrine effects of relaxin overexpression in mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:407–414. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorlov IP, Kamat A, Bogatcheva NV, Jones E, Lamb DJ, Truong A, et al. Mutations of the GREAT gene cause cryptorchidism. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2309–2318. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.19.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves PN, Tomer Y, Davies TF. Cloning and sequencing of a 1.3 KB variant of human thyrotropin receptor mRNA lacking the transmembrane domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:1135–1143. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91315-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halls ML, Bathgate RA, Summers RJ. Relaxin family peptide receptors RXFP1 and RXFP2 modulate cAMP signaling by distinct mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:214–226. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halls ML, Bond CP, Sudo S, Kumagai J, Ferraro T, Layfield S, et al. Multiple binding sites revealed by interaction of relaxin family peptides with native and chimeric relaxin family peptide receptors 1 and 2 (LGR7 and LGR8) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:677–687. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.080655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser JE, Anderson RG. Hypertonic media inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis by blocking clathrin-coated pit formation. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hida T, Takahashi E, Shikata K, Hirohashi T, Sawai T, Seiki T, et al. Chronic intracerebroventricular administration of relaxin-3 increases body weight in rats. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2006;26:147–158. doi: 10.1080/10799890600623373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaw FL. Experimental relaxation of the pubic ligament of the guinea pig. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1926;23:661–663. [Google Scholar]

- Hombach-Klonisch S, Hoang-Vu C, Kehlen A, Hinze R, Holzhausen HJ, Weber E, et al. INSL-3 is expressed in human hyperplastic and neoplastic thyrocytes. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:993–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY. New insights into the evolution of the relaxin-LGR signaling system. Trends Endocrin Met. 2003;14:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00106-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Kudo M, Chen T, Nakbayashi K, Bhalla A, Van Der Spek PJ, et al. The three subfamilies of leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1257–1271. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Liang SG, Hsueh AJ. Characterization of two LGR genes homologous to gonadotropin and thyrotropin receptors with extracellular leucine-rich repeats and a G protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane region. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1830–1845. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.12.0211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Nakabayashi K, Nishi S, Kumagai J, Kudo M, Sherwood OD, et al. Activation of orphan receptors by the hormone relaxin. Science. 2002a;25:637–638. doi: 10.1126/science.1065654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Nakabayashi K, Nishi S, Kumagai J, Kudo M, Sherwood OD, et al. Activation of orphan receptors by the hormone relaxin [comment] Science. 2002b;25:671–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1065654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu SY, Semyonov J, Park JI, Chang CL. Evolution of the signaling system in relaxin-family peptides. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1041:520–529. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivell R, Bathgate R. Neohormone systems as exciting targets for drug development. Trends Endocrin Met. 2006;17:123. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson DG, Pay S, Bhoola KD. Modulation of cyclic AMP in isolated rat uterine tissue slices by porcine relaxin. J Endocrinol. 1980;87:153–159. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0870153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamat AA, Feng S, Bogatcheva NV, Truong A, Bishop CE, Agoulnik AI. Genetic targeting of relaxin and insulin-like factor 3 receptors in mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4712–4720. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K, Kumagai J, Sudo S, Chun SY, Pisarska M, Morita H, et al. Paracrine regulation of mammalian oocyte maturation and male germ cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7323–7328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307061101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of porcine ribonuclease inhibitor, a protein with leucine-rich repeats. Nature. 1993;366:751–756. doi: 10.1038/366751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobe B, Kajava AV. The leucine-rich repeat as a protein recognition motif. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:725–732. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohsaka T, Min G, Lukas G, Trupin S, Campbell ET, Sherwood OD. Identification of specific relaxin-binding cells in the human female. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:991–999. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.4.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij R, Verhoef-Post M, Grootegoed JA, Themmen AP. Alternative splicing of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor pre-mRNA: cloning and characterization of two alternatively spliced mRNA transcripts. J Endocrinol. 1998;158:127–136. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1580127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krajnc–Franken MA, Van Disseldorp AJ, Koenders JE, Mosselman S, Van Duin M, Gossen JA. Impaired nipple development and parturition in LGR7 knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:687–696. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.687-696.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Temelcos C, Bathgate RA, Smith KJ, Scott D, Zhao C, et al. The role of insulin 3, testosterone, Mullerian inhibiting substance and relaxin in rat gubernacular growth. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:900–905. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.10.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai J, Hsu SY, Matsumi H, Roh JS, Fu P, Wade JD, et al. INSL3/Leydig insulin-like peptide activates the LGR8 receptor important in testis descent. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31283–31286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Chen J, Sutton S, Roland B, Kuei C, Farmer N, et al. Identification of relaxin-3/INSL7 as a ligand for GPCR142. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:50765–50770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Eriste E, Sutton S, Chen J, Roland B, Kuei C, et al. Identification of relaxin-3/INSL7 as an endogenous ligand for the orphan G-protein-coupled receptor GPCR135. J Biol Chem. 2003b;278:50754–50764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Kuei C, Sutton S, Chen J, Bonaventure P, Wu J, et al. INSL5 is a high affinity specific agonist for GPCR142 (GPR100) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:292–300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loosfelt H, Misrahi M, Atger M, Salesse R, Vu Hai-Luu Thi MT, Jolivet A, et al. Cloning and sequencing of porcine LH-hCG receptor cDNA: variants lacking transmembrane domain. Science. 1989;245:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.2502844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna JJ, Riesewijk A, Horcajadas JA, De Van Os R, Dominguez F, Mosselman S, et al. Gene expression pattern and immunoreactive protein localisation of LGR7 receptor in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:85–90. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Kamohara M, Sugimoto T, Hidaka K, Takasaki J, Saito T, et al. The novel G-protein coupled receptor SALPR shares sequence similarity with somatostatin and angiotensin receptors. Gene. 2000;248:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazella J, Tang M, Tseng L. Disparate effects of relaxin and TGFbeta1: relaxin increases, but TGFbeta1 inhibits, the relaxin receptor and the production of IGFBP-1 in human endometrial stromal/decidual cells. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1513–1518. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan BM, Stanley SA, Smith KL, Minnion JS, Donovan J, Thompson EL, et al. Effects of acute and chronic relaxin-3 on food intake and energy expenditure in rats. Regul Pept. 2006;136:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan BM, Stanley SA, Smith KL, White NE, Connolly MM, Thompson EL, et al. Central relaxin-3 administration causes hyperphagia in male Wistar rats. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3295–3300. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misrahi M, Beau I, Ghinea N, Vannier B, Loosfelt H, Meduri G, et al. The LH/CG and FSH receptors: different molecular forms and intracellular traffic. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1996;125:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03953-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muda M, He C, Martini PG, Ferraro T, Layfield S, Taylor D, et al. Splice variants of the relaxin and INSL3 receptors reveal unanticipated molecular complexity. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:591–600. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Yamashita S, Omori Y, Minegishi T. A splice variant of the human luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor modulates the expression of wild-type human LH receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1461–1470. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nef S, Parada LF. Cryptorchidism in mice mutant for Insl3. Nat Genet. 1999;22:295–299. doi: 10.1038/10364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BT, Dessauer CW. Relaxin stimulates protein kinase C zeta translocation: requirement for cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate production. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1012–1023. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BT, Yang L, Sanborn BM, Dessauer CW. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity is required for biphasic stimulation of cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate by relaxin. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1075–1084. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MT, Showalter PR, Timmons CF, Nef S, Parada LF, Baker LA.Effects of orchiopexy on congenitally cryptorchid insulin-3 knockout mice J Urol 20021681779–1783.discussion 1783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nistri S, Bani D. Relaxin receptors and nitric oxide synthases: search for the missing link. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek PA, Gorlov IP, Sutherland RW, Houston JB, Harrison WR, Boettger-Tong HL, et al. A transgenic insertion causing cryptorchidism in mice. Genesis. 2001;30:26–35. doi: 10.1002/gene.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell DA, Mak JY, Amento EP, Unemori EN. Relaxin binds to and elicits a response from cells of the human monocytic cell line, THP-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27936–27941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren KJ, Lin F, Bathgate RA, Tregear GW, Daly NL, Wade JD, et al. Solution structure and novel insights into the determinants of the receptor specificity of human relaxin-3. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5845–5851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511210200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, Bond CP, Burton MD, Parry LJ, et al. Relaxin deficiency in mice is associated with an age-related progression of pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J. 2003;17:121–123. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0449fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, Du XJ, Summers RJ, Amento EP, et al. The relaxin gene-knockout mouse: a model of progressive fibrosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005a;1041:173–181. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CS, Zhao C, Yang Q, Wang H, Tian H, Tregear GW, et al. The relaxin gene knockout mouse: a model of progressive scleroderma. J Invest Dermatol. 2005b;125:692–699. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanborn BM, Kuo HS, Weisbrodt NW, Sherwood OD. The interaction of relaxin with the rat uterus. I. Effect on cyclic nucleotide levels and spontaneous contractile activity. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1210–1215. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-4-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Layfield S, Riesewijk A, Morita H, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Characterization of the mouse and rat relaxin receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005a;1041:8–12. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Layfield S, Yan Y, Sudo S, Hsueh AJ, Tregear GW, et al. Characterization of novel splice variants of LGR7 and LGR8 reveals that receptor signaling is mediated by their unique LDLa modules. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34942–34954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602728200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. LGR7-truncate is a splice variant of the relaxin receptor LGR7 and is a relaxin antagonist in vitro. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005b;1041:22–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo S, Kumagai J, Nishi S, Layfield S, Ferraro T, Bathgate RA, et al. H3 relaxin is a specific ligand for LGR7 and activates the receptor by interacting with both the ectodomain and the exoloop 2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7855–7862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton SW, Bonaventure P, Kuei C, Roland B, Chen J, Nepomuceno D, et al. Distribution of G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)135 binding sites and receptor mRNA in the rat brain suggests a role for relaxin-3 in neuroendocrine and sensory processing. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;80:298–307. doi: 10.1159/000083656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Iijima N, Miyamoto Y, Fukusumi S, Itoh Y, Ozawa H, et al. Neurons expressing relaxin 3/INSL 7 in the nucleus incertus respond to stress. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1659–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tena-Sempere M, Manna PR, Huhtaniemi I. Molecular cloning of the mouse follicle-stimulating hormone receptor complementary deoxyribonucleic acid: functional expression of alternatively spliced variants and receptor inactivation by a C566T transition in exon 7 of the coding sequence. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1515–1527. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.6.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Westhuizen E, Sexton PM, Bathgate RA, Summers RJ. Responses of GPCR135 to Human Gene 3 (H3) Relaxin in CHO-K1 Cells Determined by Microphysiometry. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1041:332–337. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson TN, Speed TP, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Evolution of the relaxin-like peptide family. BMC Evol Biol. 2005a;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson TN, Speed TP, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Coevolution of the relaxin-like peptides and their receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005b;1041:534–539. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson TN, Speed TP, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Evolution of the relaxin-like peptide family: from neuropeptide to reproduction. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005c;1041:530–533. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y, Cai J, Fu P, Layfield S, Ferraro T, Kumagai J, et al. Studies on soluble ectodomain proteins of relaxin (LGR7) and insulin 3 (LGR8) receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1041:35–39. doi: 10.1196/annals.1282.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Liu SH, Erikson M, Lewis M, Unemori E. Relaxin activates the MAP kinase pathway in human endometrial stromal cells. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85:536–544. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S, Steding G, Emmen JM, Brinkmann AO, Nayernia K, Holstein AF, et al. Targeted disruption of the Insl3 gene causes bilateral cryptorchidism. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:681–691. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]